Irony exhibition at MAMbo in Bologna kills a fundamental aspect of irony

After Mozzarella in Carrozza, a large work by Gino De Dominicis that opens the exhibition Facile Ironia at the MAMbo Museum in Bologna, the path is fragmented into many works that tend to get lost and unremarkable within a setting where red and yellow walls invade and linger too long in the viewer’s head. Mozzarella in Carrozza defies any univocal interpretation, amusing and disorienting, a visual joke that hides, beneath its apparent simplicity, a deeper reflection on perception, language and the very nature of art. Time and immortality, absurd and metaphysical. Mozzarella, placed on the seat of an ’ancient black carriage, generates a conceptual short-circuit between a strong and eternal past and the transience and fragility of matter. A linguistic joke that elaborates in a strong and original way Marcel Duchamp’s ready-made, which will then accompany the whole exhibition like a cumbersome ghost.

All modern and contemporary art is always based on a conceptual gap that challenges the classical definition of a work of art, and refers to something necessarily “ironic.” For this reason, in addition to a bitter, conceptual irony that pervades modern and contemporary, works that were more frontal and immediate with respect to a complex and pulsating reality that we experience strongly outside museums in 2025 would have been needed in the exhibition. Missing, for example, are artists like Gabriele Picco with his ironic and dreamlike painting, and like Giulio Alvigini who was able to decline the culture of memes on the art world. At the same time, artists like Riccardo Baruzzi and Federico Tosi (to give two examples) seem gratuitous and forced choices.

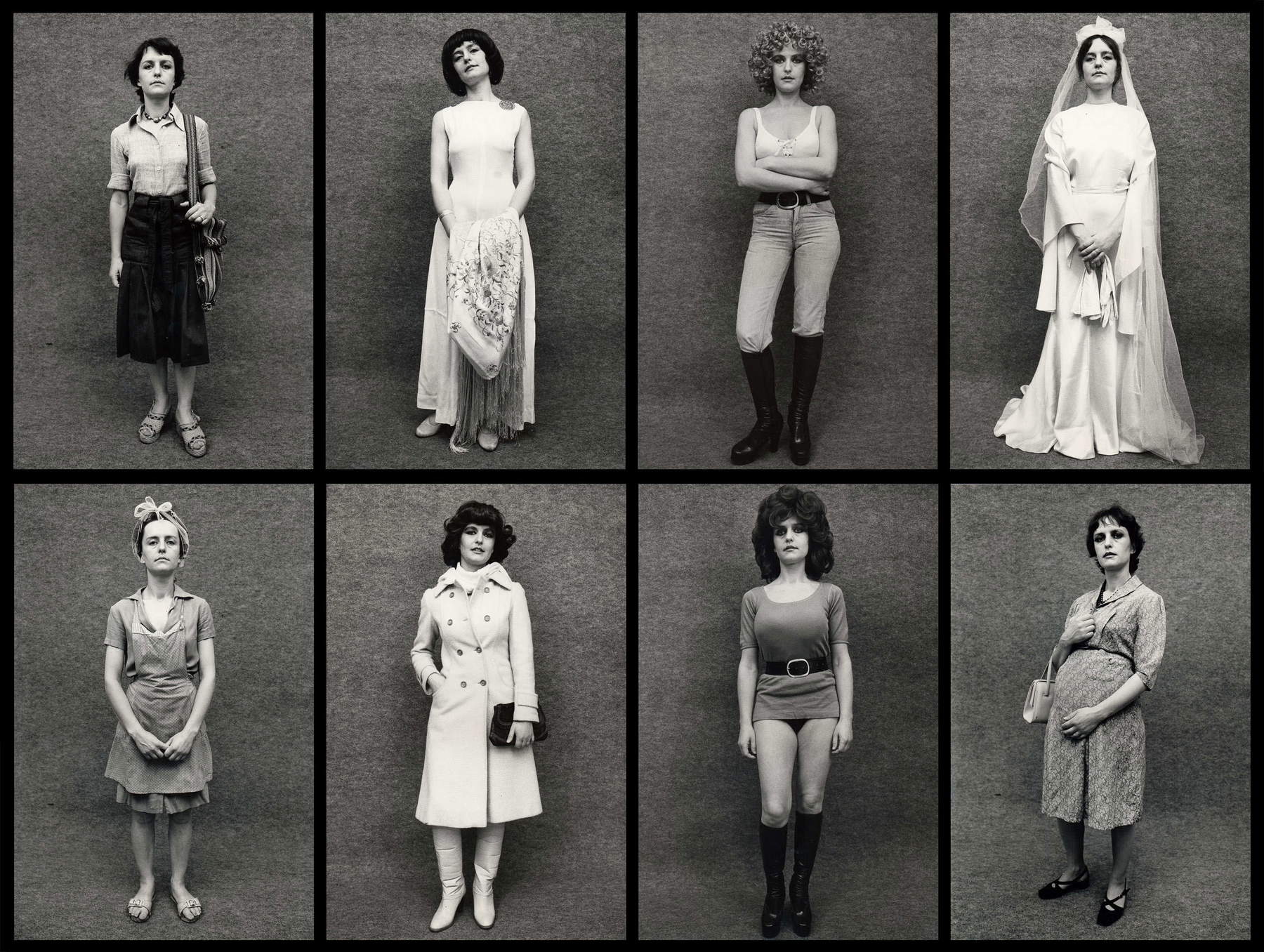

Among the many not-so-large works, small black-and-white photos, drawings, small interventions, we, for example, missed Roberto Fassone’s work, despite having made no less than two visits to the exhibition, while we liked the works of Italo Zuffi, Maurizio Mercuri (though limited) and Francesco Vezzoli. Too small and minimal were the works by Monica Bonvicini and Lara Favaretto, which, while hinting at the budget halving problems the museum has faced in recent years, also hinted at paths where irony does not actually have such a strong and preponderant presence. The feeling is that a more playful and frontal complement would have been needed in the exhibition than, for example, the subtle and conceptual irony of Italo Zuffi following for many days and photographing the gallerist who had rejected him as an artist.

The part of the exhibition devoted toirony in feminist art does not restore the importance of this movement: there are works that are certainly important from a historical perspective, but they nevertheless appear weak and have little incident to compete with the complexity of 2025. In general, to understand and enter the works in the exhibition, one has to read a lot, lots of long captions written in small print on a colored background. This, if you think about it, kills a fundamental aspect of irony: namely, immediacy. You get a feeling similar to having to explain a joke. If this happens, we obviously lose that frontality and immediacy that are fundamental to activating the ironic dimension of the work. If a viewer were to read all the captions that are in the exhibition and the texts inside many of the works, it would take hours and hours, thus heavily affecting his or her experience.

Then at MAMbo we find Pascali, Boetti, Accardi, Cattelan: all great artists, but they also lose out in the exhibition, with works that are suffocated by the colors of the walls and the many works around them. Cattelan’s pigeons, stationary and taxidermied(Ghosts), lose bite, and there is still a feeling of dissatisfaction, as if those pigeons, to affect 2025 (the work dates back to 1997), should at least be alive.

This exhibition, while demonstrating an effort in a historical sense to read the fifty years of the MAMbo museum, demonstrates once again the crisis of contemporary art and the art system in defining ways, attitudes, visions, and attitudes that are useful in dealing with our present. The feeling is that the artists and curators of the latest generations, who emerged between the late 1990s and the present day, are as if stranded in the shallows of the twentieth century, the ready-made, and the postmodern, without the citation being able precisely to become a bridge to effectively deal with the contemporary.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.