by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 08/04/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Poetry and Pottery. An Unprecedented Adventure Between Ceramics and Visual Poetry' (CAMeC, La Spezia, January 26 to April 29, 2018)

Of the thousands of works produced by the avant-gardists of Visual Poetry from the 1960s to the present, very few use a ceramic medium: a few dozen pieces that do not exceed three hundred. Most of these poems on ceramics have been brought together, following valuable research work, in a comprehensive exhibition entitled Poetry and Pottery. An unprecedented adventure between ceramics and Visual Poetry and which is on display in the first floor rooms of CAMeC (La Spezia) until April 29. A reconnaissance that spans almost sixty years of history, reconstructing one of the most fruitful experiences in recent art history, gathering important works belonging to a strand little known even to scholars. Little known, insofar as little practiced: it took the pioneering research and iron will of Sarenco (real name Isaia Mabellini, Vobarno, 1945 - Salò, 2017) to convince many of the protagonists of that season to try their hand at ceramic art. Sarenco was a visionary artist, who knew how to expand the boundaries of Visual Poetry outside Italy (“Visual Poetry” is, after all, an expression used to connote the international character of this experience) and who nurtured the dream, he who from his youth had never stopped producing ceramics, of dispelling the myth that ceramics was a material for painters and not for poets. Thus, in 1989, after participating in one Documenta and two Venice Biennales (and two more would await him in the future), and when he was still directing his Domus Jani, a center for international artistic research, he wanted to invite many of his friends to try their hand at ceramics.

Many of the big names in Visual Poetry, from Lamberto Pignotti to Emmett Williams, from Julien Blaine to Eugenio Miccini, from Jean-François Bory to Ugo Carrega, accepted Sarenco’s invitation, who in 2013 regretted that all the ceramics made in that context had been dispersed among various collections, and said that “it would be nice one day, for those who wanted to deal with it, to try to bring them all together to publish a book documenting all this interesting experience.” Sarenco, unfortunately, did not make it in time to see his second dream fulfilled, since he passed away in February 2017, with research still in progress. But that desire has taken shape in the CAMeC exhibition, which finds fertile ground in Liguria for at least two good reasons. The first: Liguria has always been a land of ceramics and, in the twentieth century, all the great artists who wanted to experiment with ceramics (a few names at random: Lucio Fontana, Asger Jorn, Wilfredo Lam) chose to transit through the Ligurian Sea. The second: La Spezia was, in the 1960s, the propelling center of Gruppo ’63, from which many of the visual poets came, and in recent years CAMeC has given rise to an important critical rereading of that era (in the catalog, Marzia Ratti traces all the exhibitions that the La Spezia museum has dedicated to Visual Poetry), culminating with a conference dedicated precisely to Gruppo ’63, and with the exhibition Da un’avanguardia all’altra. Verbovisual Experiences between Gruppo ’63 and Gruppo ’70, which is profound and also cloaked in a slight and ill-concealed nostalgic vein.

Visual Poetry is defined by exhibition curator Giosuè Allegrini, in his essay in the catalog, as “the fulcrum of a creative system that managed to detach poetry from the limited context of the page and lead it beyond.” With ideas rooted in Guillaume Apollinaire’s Calligrammes, Stéphane Mallarmé’s Coup de dés, Futurist paroliberalism, and the works of the “very new poets,” Visual Poetry uses the double code of words and images without distinguishing between these two entities, but simply using them, while “never forgetting their provenance” and gaining meaning precisely “from the encounter-counterpoint of the word itself with the co-associated image, often drawn from advertising clippings, from photostories, from popular readings, that is, from those centers of formal and linguistic elaboration closest to the masses.” “Visual poetry,” wrote Michele Perfetti in 1971, “is a multiplied sign of information that dynamically expresses our time, potentially in direct competition with the more conspicuous and stranded means of mass communication.” Born to express its dissent against modern capitalist society, endowed with a vigorous subversive charge, militant art and characterized by strong ideological connotations, Visual Poetry occupies a prominent place in the history of Italian art. And all these elements are obviously not lacking in the production on ceramics, which for many visual poets represented a kind of challenge. “Ceramics,” writes Lamberto Pignotti in one of his contributions published in the catalog, “induces me to caution by appearing to me as a particularly fragile material that is predisposed to cracking, to breaking. And yet, this fragility gives value to the artist’s creation: ”it is precisely the history of art that has accustomed us to consider the ruptures and fragments procured by the hand of time, with that particular attention that is connected to an increase in aesthetic charge. The sublime case of the Venus de Milo, which if it had been intact would probably have aroused a lesser degree of enthralling seduction, is worth all."

|

| Entrance to the Poetry and Pottery exhibition at CAMeC (La Spezia) |

|

| Hall of the Poetry and Pot tery exhibition at CAMeC (La Spezia) |

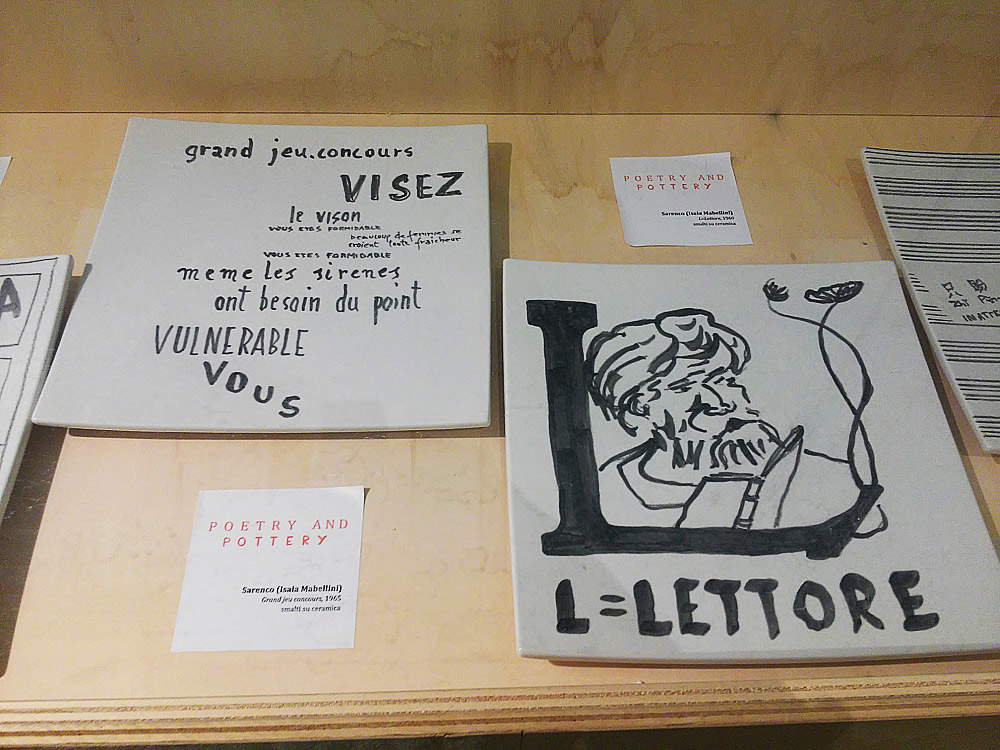

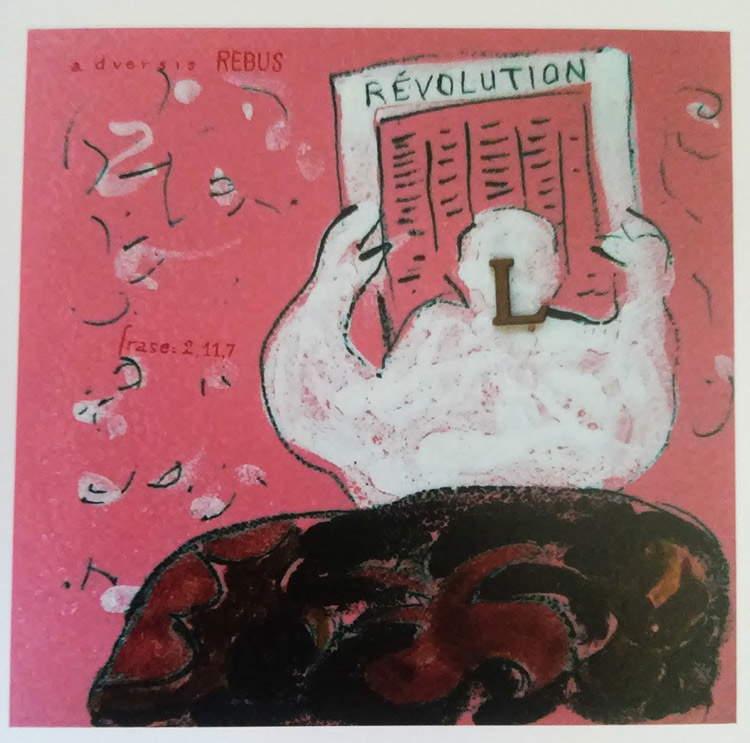

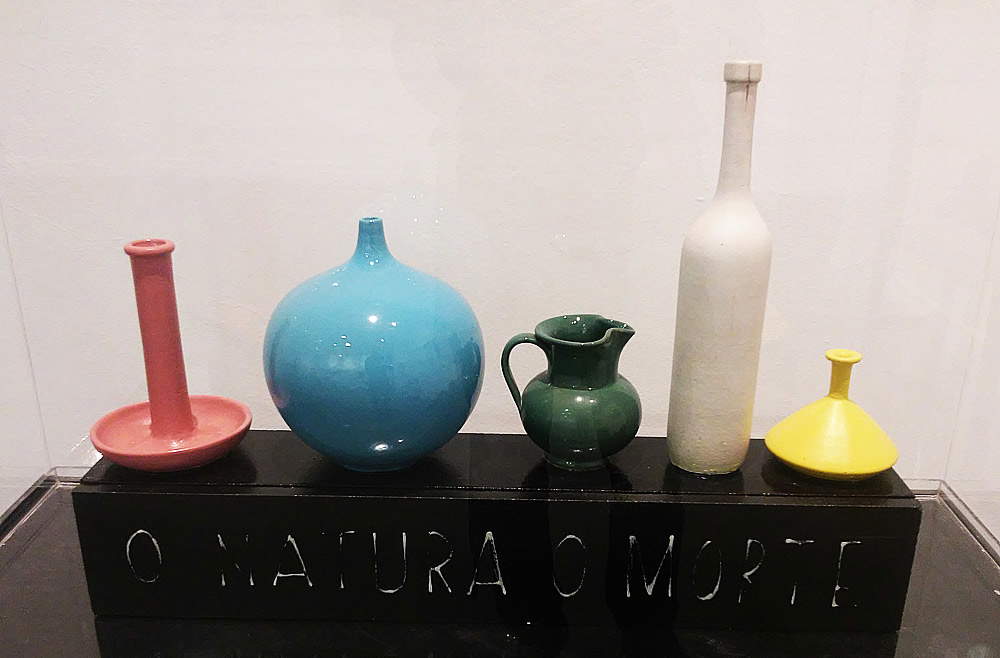

The beginnings of Visual Poetry on Pottery can be traced back, as anticipated, to the youthful experiences of Sarenco, who began creating his own poems as early as the 1960s, and the exhibition, which in the three rooms in which it is set up follows a substantially chronological iter, shows the viewer some significant examples. The earliest works, such as Grand jeu concours of 1965, are simple black phrases on a white background, which nevertheless have the merit of having opened a path, followed immediately with audacity by Eugenio Miccini (Florence, 1925 - 2007), who in 1968, using the same type of support used by Sarenco (the square plate with a side of 28.5 centimeters), with discouraged political visionariness created his ironic rebus La rivoluzione tradita. Continuing through the room, one becomes acquainted with Sarenco’s later experiments: the plate is abandoned and vases and bottles make their appearance in his production that mock Giorgio Morandi’s art, sarcastically accusing it of lacking freshness (the works Più morta che natura and O natura o morte, both from 1971, prove to be exceedingly eloquent: history and the market, as one might expect, would nevertheless reward the more resigned and less provocative Morandi).

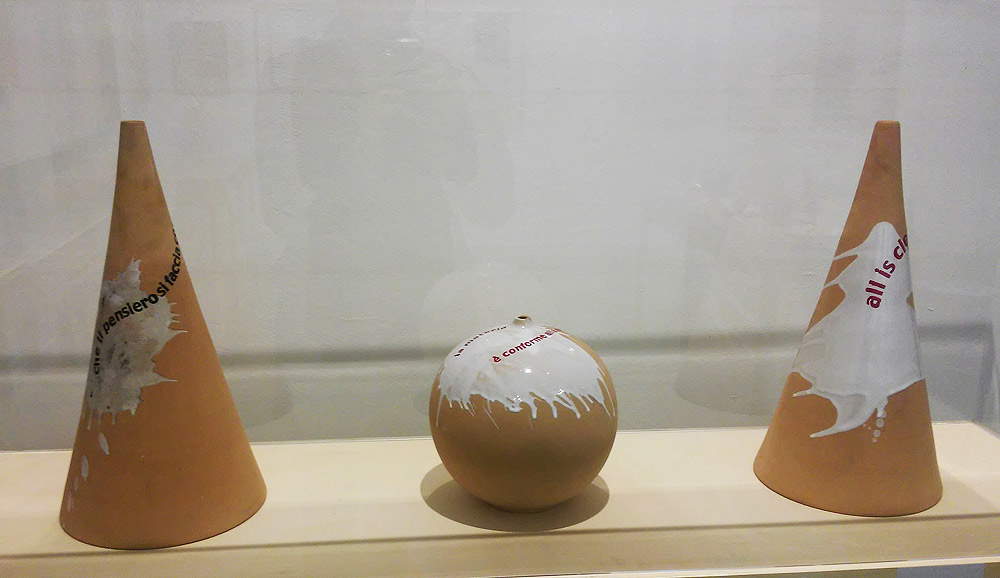

The Seventies saw the addition to the group of visual poets on ceramics of the Genoese Ugo Carrega (Genoa, 1935 - Milan, 2014), who from 1977 began to produce his own poems on ceramics (simple white phrases on a colored background) arriving then, for the first time, to affix the words on a three-dimensional surface, that is, spheres and cones that are enriched with verses with strong symbolic references(Che il pensiero si faccia, La materia è conforme alla mente, All is clear now, all works from 1986). Also in the 1980s, Sarenco had initiated his New Abstraction series: flags of the nations of the world with the phrase “new abstraction” imprinted on them in their respective languages. The idea was to create as many tiles as there were flags from all over the world (Sarenco detested borders and barriers), but it ran aground after only a few realizations (note, by the way, how the Spanish flag bears the inscription in English: the artist, in fact, did not know Spanish), only to resume it, years later, with a new cycle on the same theme (but with the technique of oil on canvas), composed of twenty-seven flags and exhibited for the first time in 2012, exactly thirty years after the cycle on ceramics was started.

|

| Left: Sarenco, Grand Jeu Concours (1965; glazes on ceramic, 28.5 x 28.5 cm; Private collection). Right: Sarenco, L=Lector (1969; glazes on ceramic, 28.5 x 28.5 cm; Scatizzi Collection) |

|

| Eugenio Miccini, La rivoluzione tradita (1968; glazes and letters pasted on ceramic, 28.5 x 28.5 cm; Scatizzi Collection) |

|

| Sarenco, O natura o morte (1971, glazes on ceramic, 12 x 72 x 48 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Ugo Carrega, from left to right: Che il pensiero si faccia (1987; glazes on ceramic, vase height 46 cm, base diameter 23 cm; Sarenco Collection), La materia è conforme alla mente (1986; glazes on ceramic, spherical vase height 23 cm, diameter 22.5 cm; Sarenco Collection), All is clear now (1997; glazes on ceramic, vase height 46 cm, base diameter 23 cm; Berardelli Collection) |

|

| Sarenco, More Dead Than Nature (1971, glazes on ceramic, 24 x 72 x 78 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Sarenco, from top to bottom: Nouvelle abstraction française, New Italian abstraction and New Spanish abstraction (all 1982, glazes on ceramic, 20 x 30 cm; Scatizzi Collection) |

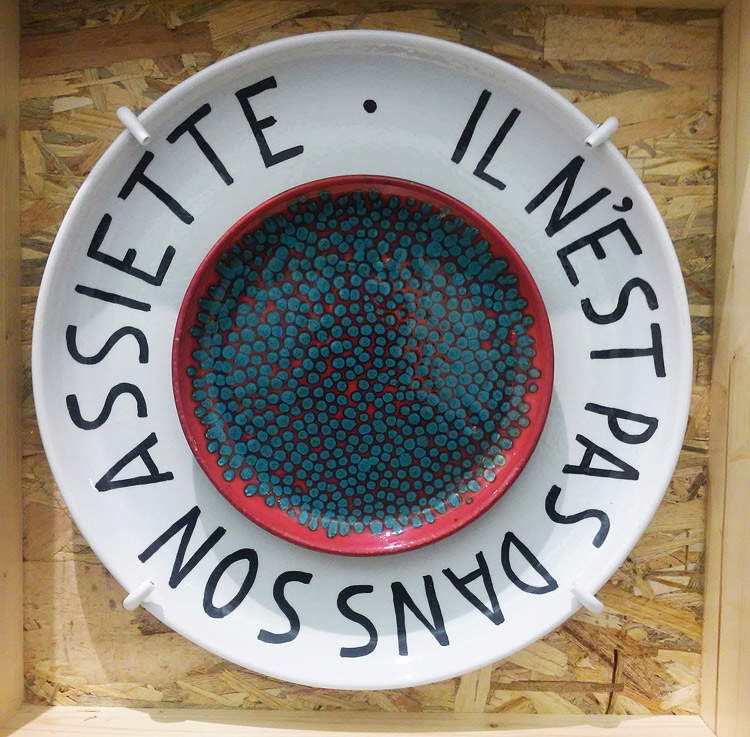

The rest of the exhibition, on the other hand, testifies to the achievements since 1989, the year in which Sarenco kicked off his own project of involving visual poets in the creation of works on ceramics (it should be noted that the poets who gave life to Sarenco’s dream were honored by him, in 1998, with the work All the Poets of My Heart, shown at the La Spezia exhibition). Ceramics thus becomes a medium that allows many poets to express their art. Among the earliest works the public encounters are the compositions of Alain Arias-Misson (Brussels, 1936), who uses ceramics by modeling various objects to recreate situations that allude to the everyday reality of his subjects (such as The Divorced or The Boyfriends). Julien Blaine (Rognac, 1942), on the other hand, uses irony and double entendre to create a series of plates with strong, acidic decorations in the center, which almost seem to have come out of lysergic hallucinations, and which all bear on the brim the phrase Il n’est pas dans son assiette (which literally means “he is not in his plate,” but which is also an idiomatic phrase that in Italian is rendered as “non si sente bene,” “he is not well”).

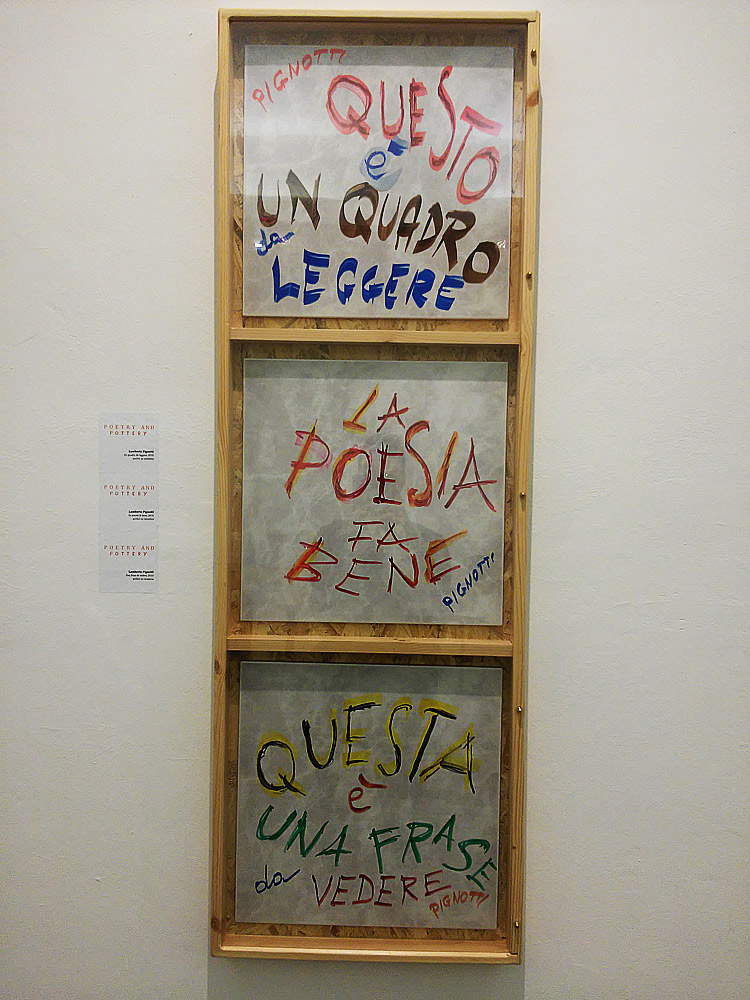

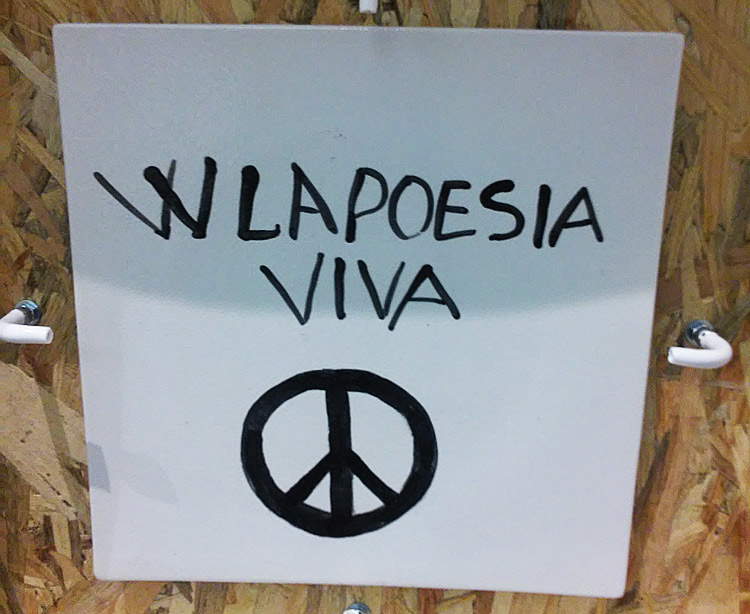

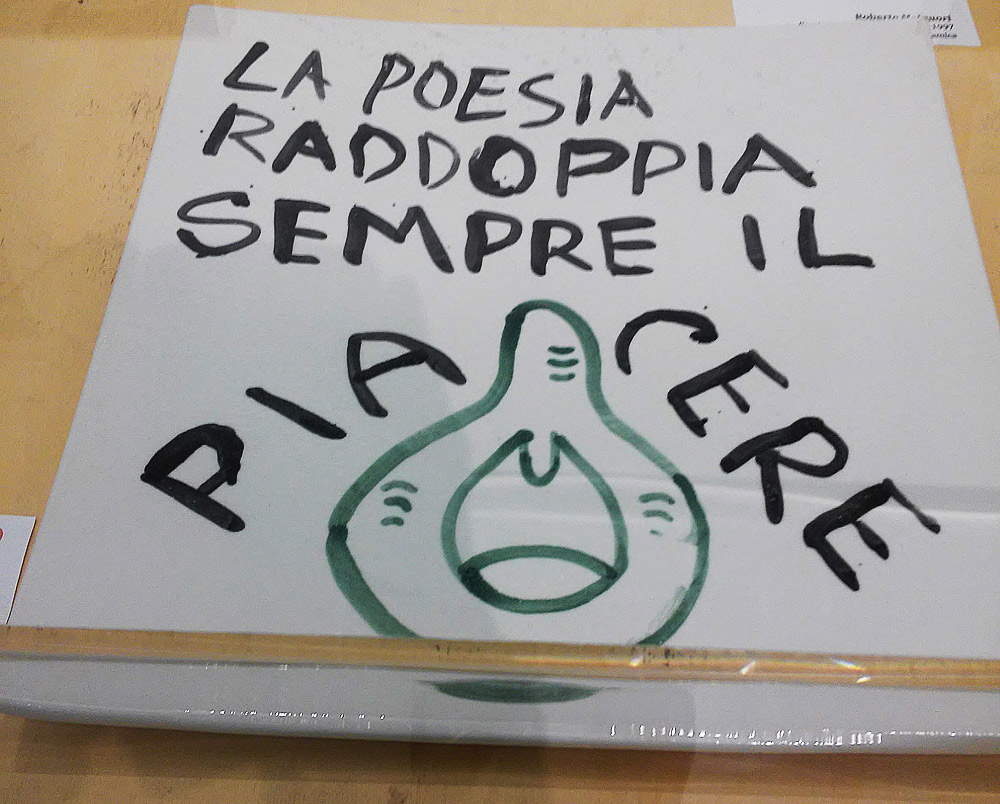

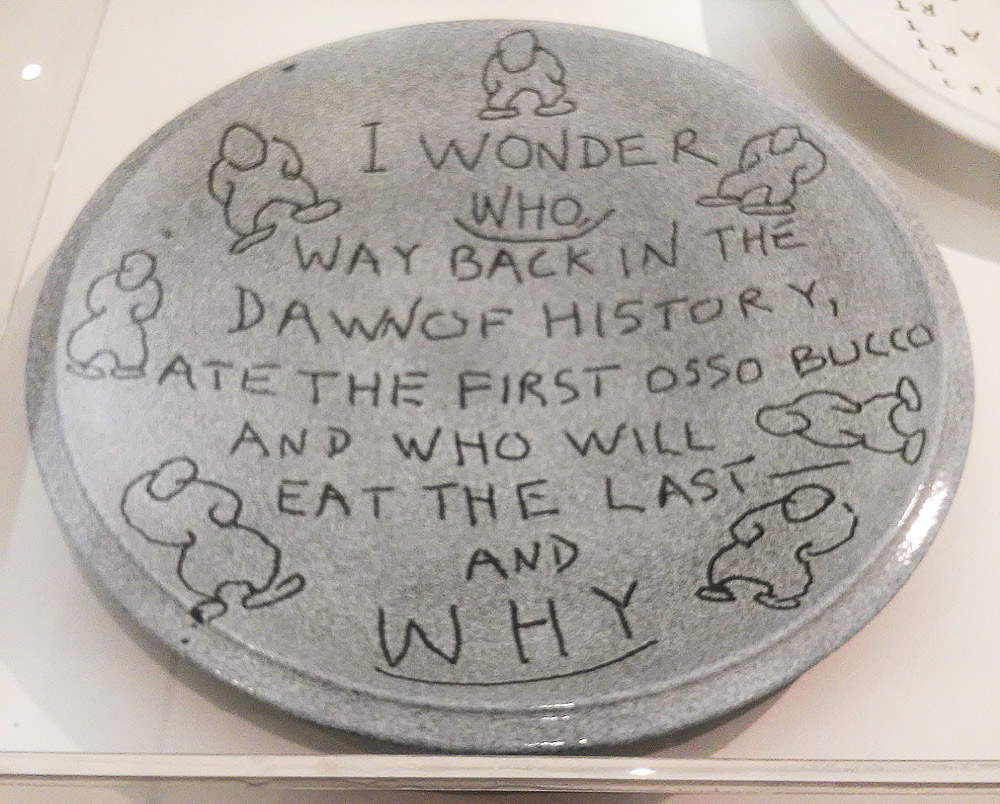

Of the artists of the Gruppo ’ 63 and Gruppo ’70, Sarenco succeeds in involving, among others, Luigi Tola (Genoa, 1930 - 2014), Lucia Marcucci (Florence, 1933), Lamberto Pignotti (Florence, 1926) and Roberto Malquori (Castelfiorentino, 1929), who use the ceramic plate as a medium to which they entrust short verses, ironic, profound and direct, typical of their style, reflecting on the mixture of languages(This is a picture to read, This is a sentence to see by Lamberto Pignotti) or on the very meaning of poetry(From here along words by Luigi Tola), even in very elementary tones(Poetry is good for you by Pignotti, Alt! Poetry by Lucia Marcucci). Malquori also reflects on poetry( 1997’sW la poesia viva: practically the title of last year’s Venice Biennale), even dwelling on the marriage of poetry and love(La poesia è amore), which is then transformed into erotic pleasure(La poesia raddoppia sempre il piacere, with writing accompanied by a drawing of a female genital organ showing much of an already well-stimulated clitoris). Accompanying the visitor on the way out are plates by Emmett Williams (Greenvile, 1925 - Berlin, 2007): particularly interesting is the one in which the character wonders I wonder who, way back in the dawn of history, ate the first osso bucco (sic) and who will eat the last and why ("I wonder who, way back in the dawn of time, ate the first osso bucco, and who will eat the last, and why.") is a reference to a 1964 performance that Williams conducted with Robert Filliou that would give the title to a poem entitled The last french-fried potato (“The last french fry”). The two recited verses (Williams in English and Filliou in French) while eating French fries: each verse corresponded to a french fry eaten, and the poem ended when they finished the fries. The last two lines read, “I wonder who, way back in the dawn of history, ate the first / il dit: je me demande qui, dans la nuit des temps, a mangé la première” (“I wonder who, way back in the dawn of time, ate the first [potato chip] / he says: I wonder who, way back in the dawn of time, ate the first”), as if to leave the poem hanging on a reflection about the origins of the art of poetry itself.

|

| Sarenco, All the Poets of My Heart (1998; glazes on ceramic; Sarenco Collection) |

|

| Alain Arias-Misson, The Boyfriends (1997; glazes on ceramic and wood, 50 x 100 x 19 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Alain Arias-Misson, The Divorced (1997; enamels on ceramic and wood, 33 x 62 x 36.5 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| The series Il n’est pas dans son assiette by Julien Blaine |

|

| Julien Blaine, Il n’est pas dans son assi ette (1998; enamels on ceramic, 41.5 cm diameter; Scatizzi Collection) |

|

| Lamberto Pignotti, From top to bottom: This is a picture to read, Poetry is good, This is a sentence to see (all 2010, glazes on ceramic, 43 x 43 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Lucia Marcucci, Alt! Poetry (1997, glazes on ceramic, 41 cm diameter; Molvena, Bonotto Foundation) |

|

| Roberto Malquori, W la poesia viva (1997, enamels on ceramic, 28.5 x 28.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Roberto Malquori, Poetry always doubles the pleasure (1997, glazes on ceramic, 28.5 x 28.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Emmett Williams, Osso bu cco (1989-1991, glazes on pottery, 55 cm diameter; Sarenco Collection) |

In the Poetry and Pottery catalog (an excellent tool for in-depth study but also for approaching visual poetry, since it also contains biographies of all the artists, as well as a long essay by Giosuè Allegrini with a markedly didactic slant: in fact, it traces the origins and history of the movement, and the history of some fundamental previous experiences), Lamberto Pignotti asks whether there is a future for Visual Poetry, and to this question he provides a twofold answer: if by “Visual Poetry” he means “that which was codified, defined and passed into the record in the 1960s,” then “the answer can only be negative.” However, the fact that Visual Poetry has acquired a “classicity” of its own is, for Pignotti, a symptom of the fact that this art form has potential that is “far from dying out,” and the artist is confident that Visual Poetry “can still show some good ones.” One cannot help but remark, however, that back in 1999, on the very occasion of an exhibition on Visual Poetry, Lucilla Saccà argued that visual poets have lost their social and political battle. “The overwhelming power of the mass media,” the scholar wrote, “has increased out of all proportion and the consequent leveling of information has created a dangerous cultural homogenization, a generalized crisis of ideological values, an impoverishment of language that leaves no one indifferent, the cynicism of capitalist society has constructed a series of peripheral wars, which everyone experiences as very distant, with their baggage of horror and ruin.” The cultural stalemate that ensued would have triggered “a tenacious and constant distrust of contemporary cultural expressions, except for those aspects closely linked to commerce such as fashion,” with the consequence that “retreating to quotations and the unquestionable values of the past seem to be the most reassuring path.”

What future, then, for Visual Poetry? On closer inspection, this art form catalyzed a tension that later became highly topical: the extension of the possibilities of writing, which expanded to the point of developing ways to express even functions not necessarily related to merely linguistic content. The visual poets have thus played the role of visionary forerunners, but it is indeed difficult to say whether the near future may still hold spaces for a poetic-artistic avant-garde to pick up the baton of that of the historical poets. The exhibition Poetry and Pottery itself, a coherent and comprehensive survey of research, turns its gaze mostly to the past. However, it should also be noted that Sarenco himself never believed in the exhaustion of the propositional drive and the overcoming of Visual Poetry (and, of course, poetry tout court). Only the languages and modes of expression change. And in a final piece of writing, dated November 2016, Sarenco was able to envision the poet of the future: “the new poet is a pantophagous monster who asks no one’s permission, who crosses societies, religions and politics, far from being recovered by gold and honors.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.