One episode alone would be enough to give an idea of the temperament of Giovanni Battista Scultori, an elusive artist who worked in Giulio Romano’s Mantua, working among stuccoes, carvings, drawings, and engravings. It is a discussion Scultori had with a cardinal, Ippolito Capilupi, apostolic nuncio to Venice in 1562, the year in which a working relationship between the artist and the prelate is documented. Capilupi had asked him for two works, a silver crucifix and a pace, or liturgical tablet used during Mass. Scultori then wrote Capilupi a letter in which he told him that he had made the crucifix on the model of a similar object owned by Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga, but he made him understand, not too veiledly, that making the Christ “the cloth all adored,” that is, the golden loincloth, would not have been a great idea, since Cardinal Gonzaga “dise che ogni plebeo lo vol adorato.” In a nutshell, Sculptori allowed himself to tell his commissioning cardinal that a Christ with a golden loincloth would be the stuff of boors.

The letter, written in a very precise, clear, modern, almost geometric, easy-to-read handwriting, is preserved at the State Archives in Mantua and is among the most interesting pieces that make up the exhibition Giovan Battista Scultori. Intagliator di stampe e scultore eccellente, set up in the rooms of the Rustica in Mantua’s Ducal Palace and curated by Stefano L’Occaso, the museum’s director: it is the first exhibition entirely devoted to this artist about whom we know enough but not very much, despite his longevity (he was probably born in 1503 and disappeared at more than seventy in 1575), and despite a position we must imagine preeminent in sixteenth-century Mantua. A multifaceted figure, since he was a sculptor, engraver, carver, and perhaps also a publisher and entrepreneur active in the goldsmith’s trade, Scultori is mentioned in an obituary as “M. Gio. Batta Sculptor” and in a 1542 document as “Io. Bapta Sculptor,” which is why in the past it has been assumed that “Scultori” was his real surname, rather than an indication of his profession (in fact it appears that his surname was Veronesi). He attended the decorations of Palazzo Te as a collaborator of Giulio Romano, was active for some time as a plasterer at the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trent, was involved in the creation of some works destined for the Verona Cathedral, and was perhaps also employed in the decorations of the Stadtresidenz in Landshut together with other Italian artists. He was famous throughout Italy and even outside the peninsula. He had some problems with the Inquisition, given his frequentations. And for a time he also worked as an engraver.

That of engraving was, however, a short-lived parenthesis for Scultori: he engaged among plates, matrices and inks for only four years, as far as we know to date. From 1536 to 1540. Indeed, perhaps not even, since that 1536, inferred from only two engravings, could also be 1538, given the way Sculptori wrote the number 8, similar to 6. Consequently, very rare are his engravings. There is not a single museum in the world that has all of them, and the complete catalog of Scultori’s prints, consisting of fewer than twenty pieces, is now on display in Mantua. Why then did Scultori’s interest in engraving last so short, that is, less than a lustre out of a decades-long career? Several hypotheses have been formulated: perhaps this production was linked to some commission that came from Federico II Gonzaga, who passed away on June 28, 1540. Dead the commissioner, dead the work. Or, Scultori had decided to start his own business devoted to printmaking, and realizing that it was not as profitable as he thought, he would abandon it without much resipiscence. Or again, more simply, the association with the draughtsman, whom the exhibition identifies hypothetically, but with more than robust arguments, in the figure of Giovanni Battista Bertani, another great Mantuan of the time, had to come to an end: Having retired Scultori, the task of translating Bertani’s drawings into engravings would have fallen to Giorgio Ghisi, “one of the most accomplished engravers of the Italian Renaissance,” as David Landau called him, “a craftsman whose skills were probably unparalleled below the Alps during the second half of the sixteenth century.” The latter is perhaps the idea that might find a better and more consistent reception with what happened after 1540, given that in Gonzaga Mantua engraving productions would continue for decades.

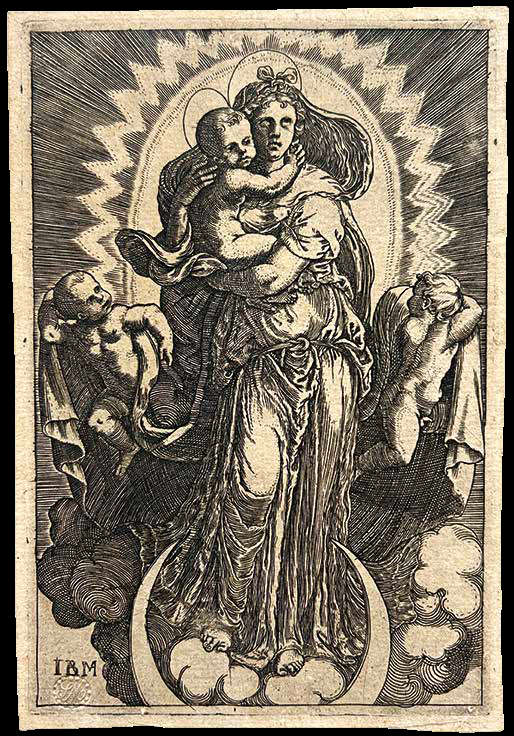

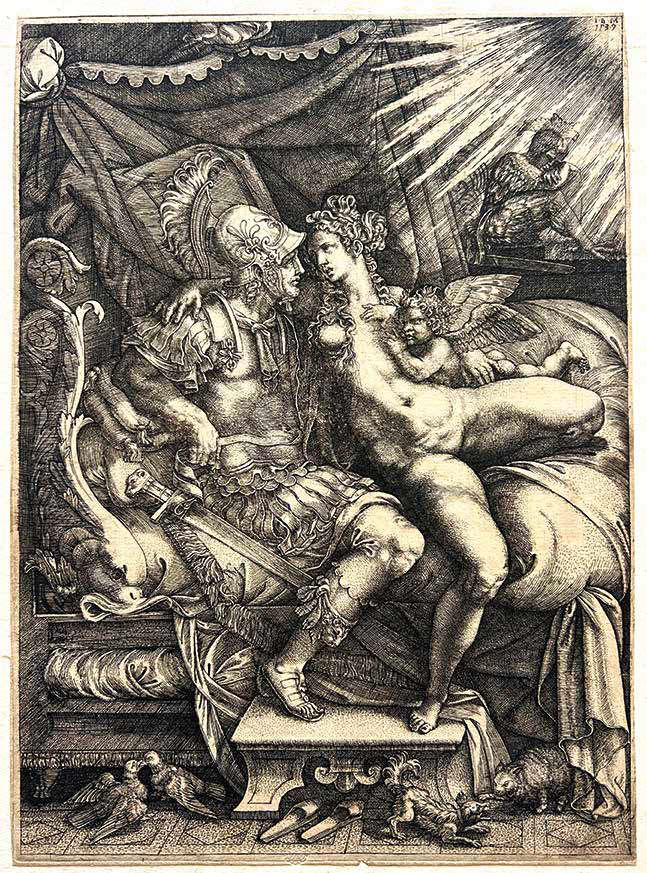

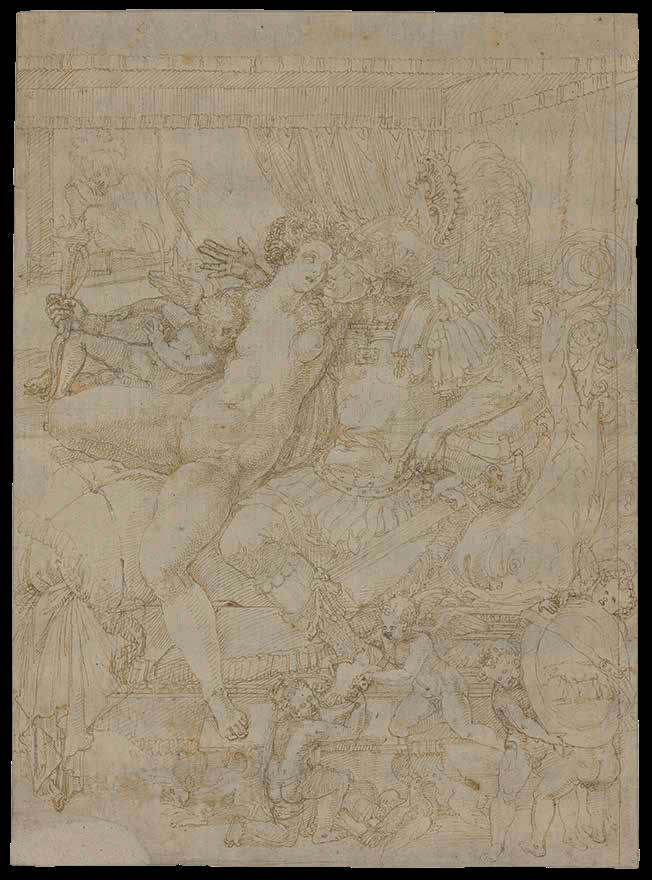

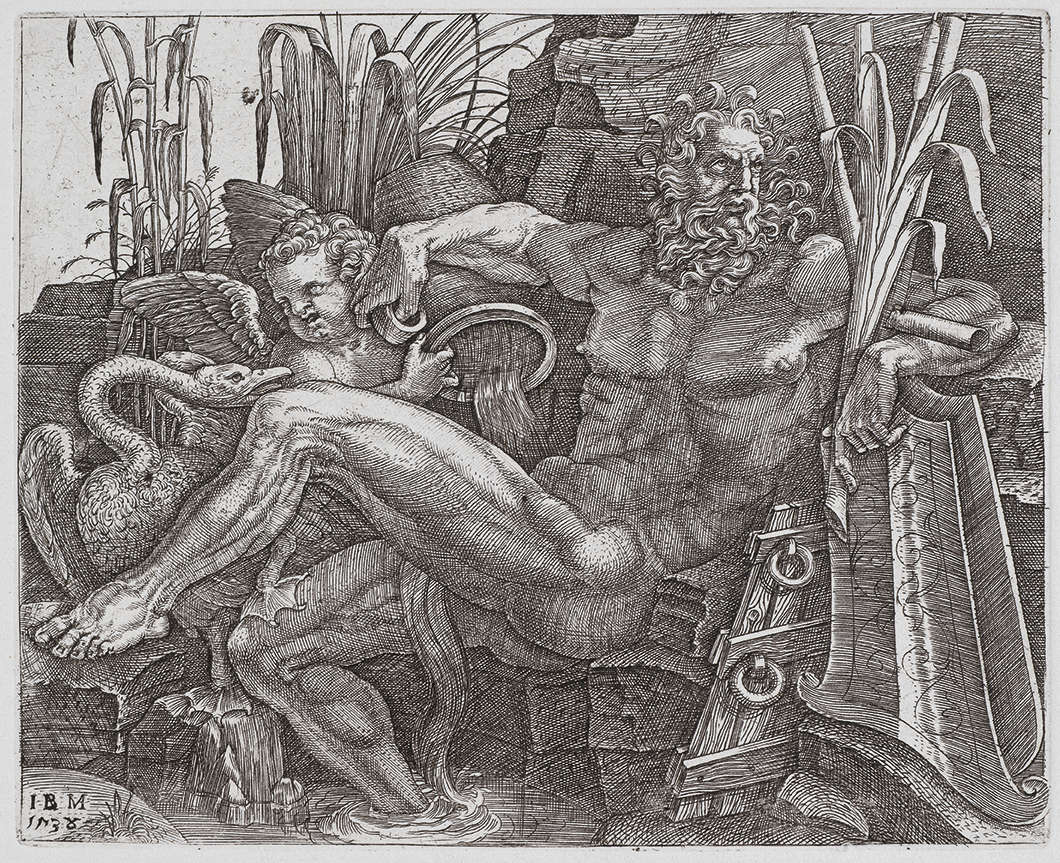

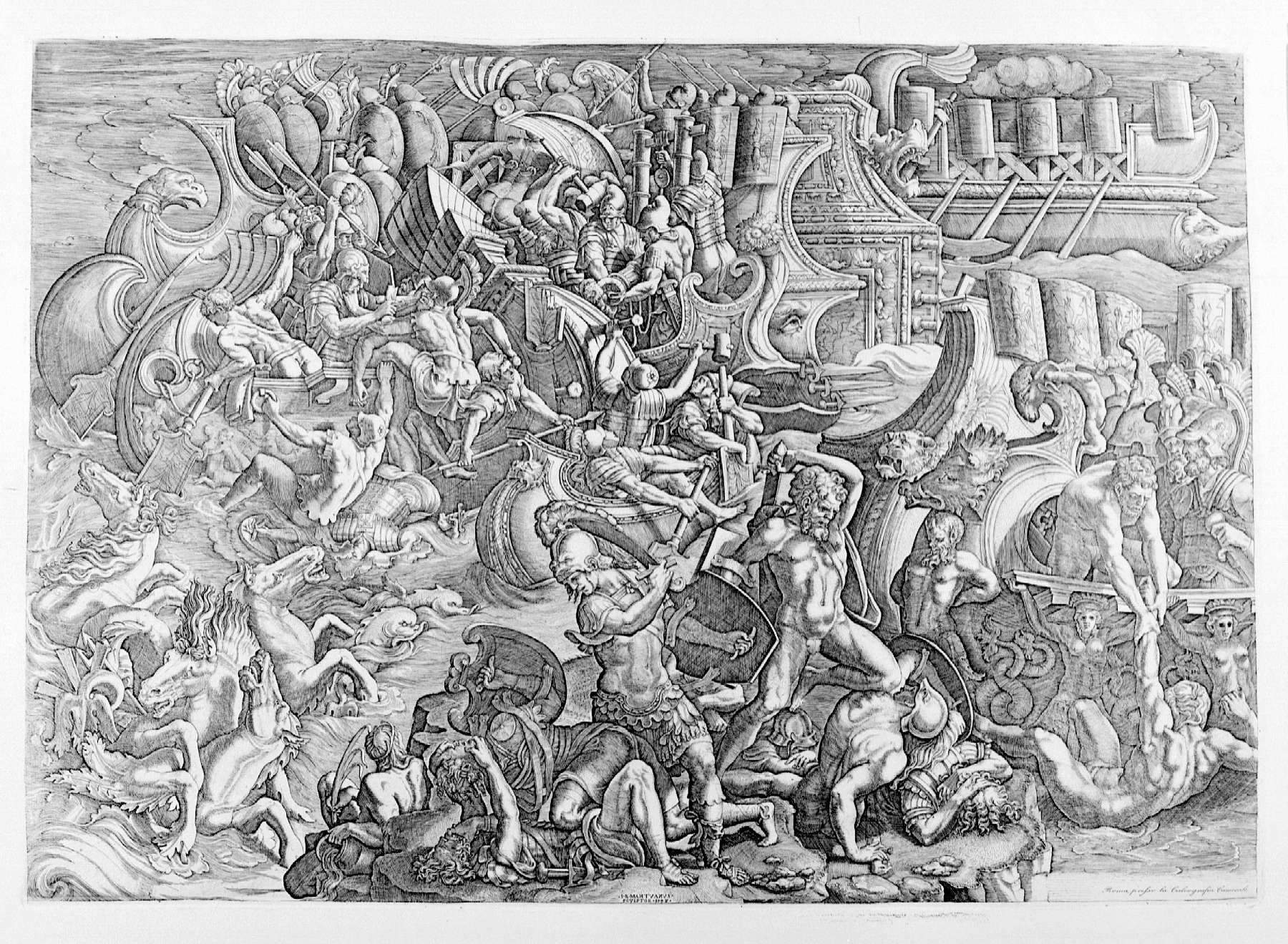

The exhibition is not set up in chronological order, but rather follows a thematic itinerary: religious subjects, biblical subjects, mythological subjects, soldiers, and battles. And it is precisely in two engravings depicting soldiers (a Captain of Flags on foot, a singular portrait of a Lansquenet soldier dressed, however, in the armor of a Roman soldier, and a print with Heads of Soldiers wearing old-fashioned helmets, the latter of which was purchased by the Palazzo Ducale di Roma) that the exhibition is divided into two sections.the latter moreover purchased by the Ducal Palace of Mantua on the very occasion of the exhibition) that one can find the date “1536” (which perhaps in reality, as anticipated, could be a 1538), and that is the oldest of those appearing in Sculptori’s prints. It is, however, around the initials IBM, or “Iohannes Baptista Mantuanus,” “John Baptist Mantuanus,” that scholars’ discussions have centered, given the ambiguity of the inscription that can be observed in all of Scultori’s prints. Some have thought that it might be Scultori’s signature: unlikely, since if the engraving bore only one signature, it was usually that of theinventor, the draughtsman, and not that of the executor. And Scultori, as a draughtsman, was not much of a draughtsman: this is well attested by the 1562 Peace, lent by the Museo Diocesano Francesco Gonzaga in Mantua, displayed in the center of the second of the exhibition’s two rooms, alongside a sketch for its composition, the letter sent to Capilupi, and an unpublished silver-plated bronze crucifix, attributed to Guglielmo della Porta, displayed to recall the object the cardinal had commissioned from Scultori. Then a Giovanni Battista, of Mantuan origin, must be found, who may have provided the drawings for the carvings: Stefano L’Occaso’s well-founded hypothesis is that the drawings for Scultori’s prints are owed not to Giulio Romano, as has long been thought, but to Giovanni Battista Bertani, a former pupil of Giulio’s, then little more than than 20 but already an independent artist, and who may have come to prominence at the Mantuan court precisely through these engravings, given his appointment as prefect of the ducal factories that came to him in 1549 without any knowledge of his relevant previous undertakings. In formal terms, Sculptori’s prints are devoid of any softness, are convulsive, result from the often bold crossing of several planes, and are worked, writes L’Occaso, “with a wide repertoire of signs, dots, quotation marks and crossed strokes, which contribute to strong chiaroscuro effects and a tense drama.” As for the content, these engravings “are the product of a court observing the antique with eyes educated by Giulio Romano, who did not limit himself to slavish revival, but created an alternative antique and gave new life to archaeological material.” Both form and substance hark back to the manners, inventions and attitude of Giovanni Battista Bertani. The main evidence, offered for the first time in this exhibition, is a drawing by Bertani depicting Mars with Venus suckling Cupid, which came on loan from the Graphische Sammlung in Munich, long believed to be a copy of an engraving by Sculptori (a specimen from the Civic Museums of Pavia is on display), alongside which the sheet is displayed. Beyond the strangeness of a possible reversed copy, such as Bertani’s drawing would be assuming that it was derived from Scultori (extremely more likely, however, that it is simply the preparatory sheet precisely because the image is in counterpart to the print), it is an idea with obvious differences from the print, a sign that theartist had to intervene later with further alterations, and then there are dissimilarities in the proportions (a copyist would have merely offered a faithful, slavish reproduction of the original image), and should one accept an advanced dating of the sheet, such as the one proposed in the past, one would have to wonder why Bertani would have copied an old print by Scultori, and without major variations, when he was already prefect of the ducal factories.

Also attributable to Bertani is the closeness to Nordic graphic art (Dürer, Altdorfer, and so on), which snakes through almost all the prints on display at the Ducal Palace, starting with the first two that the public finds along the visiting itinerary, the Madonna suckling the Child , which would seem to derive from a’homologous work by Albrecht Dürer, and theImmaculate Conception with Baby Jesus and two holding angels that follows the tradition of the Mondsichelmadonna, the image of the Virgin and Child standing on the crescent moon, typical of northern European art. Other images look instead to Italian models: there is a sample of this in the first room, where there is a printed reinterpretation of the Jupiter and Olympias that Giulio Romano had frescoed in the Camera di Psyche in Palazzo Te, a subject of which a version censored by Sculptori is also known to cover the phallus of the father of the gods with a play of shadows (the uncensored exemplar from the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna is on display instead). Tangencies with the Giulio Romano of Palazzo Te, and indeed with the Chamber of Psyche, can likewise be discerned in theAllegory of the Po River that recalls the Polyphemus painted on the walls of the Gonzaga residence, whose decorations evidently provided Sculptori with a constant repertoire for deepening that lively interest in the antique cultivated by the entire artistic milieu of Mantua in the mid-sixteenth century. Similarly Juliesque are the prints with Cupid recalling the Infant Jupiter of the National Gallery in London, or the more challenging Resurrection that also celebrates Raphael, particularly in the figure of the soldier on the ground, a quotation from the Urbino’s Expulsion of Heliodorus (but perhaps also in the same figure of Christ that echoes the Transfiguration of the Vatican Pinacoteca).

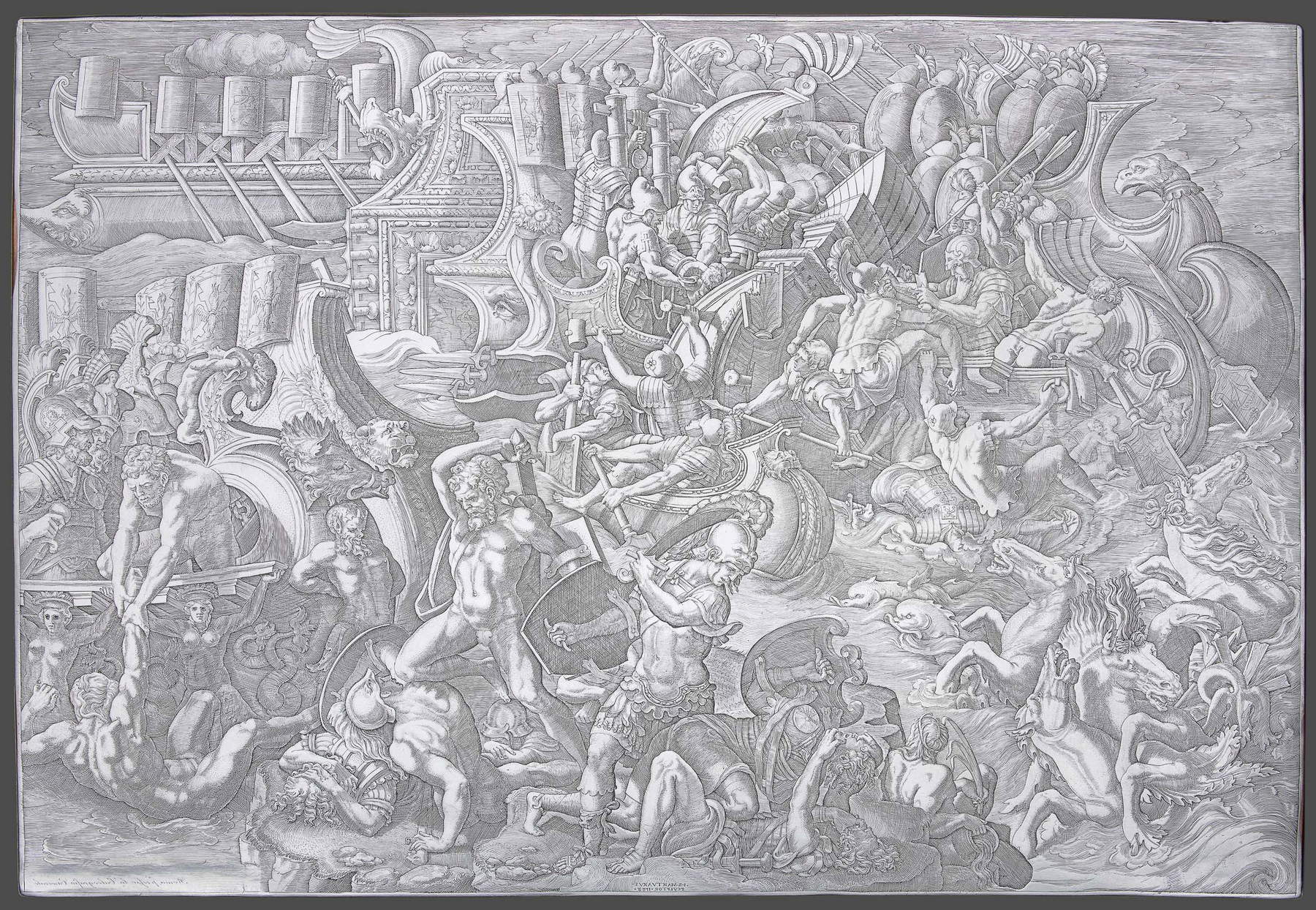

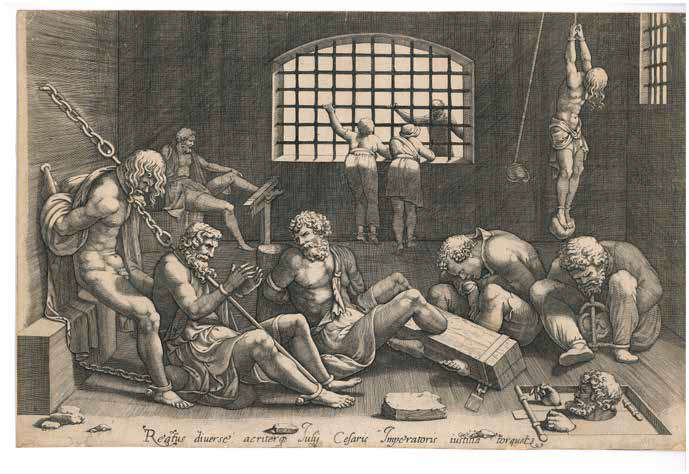

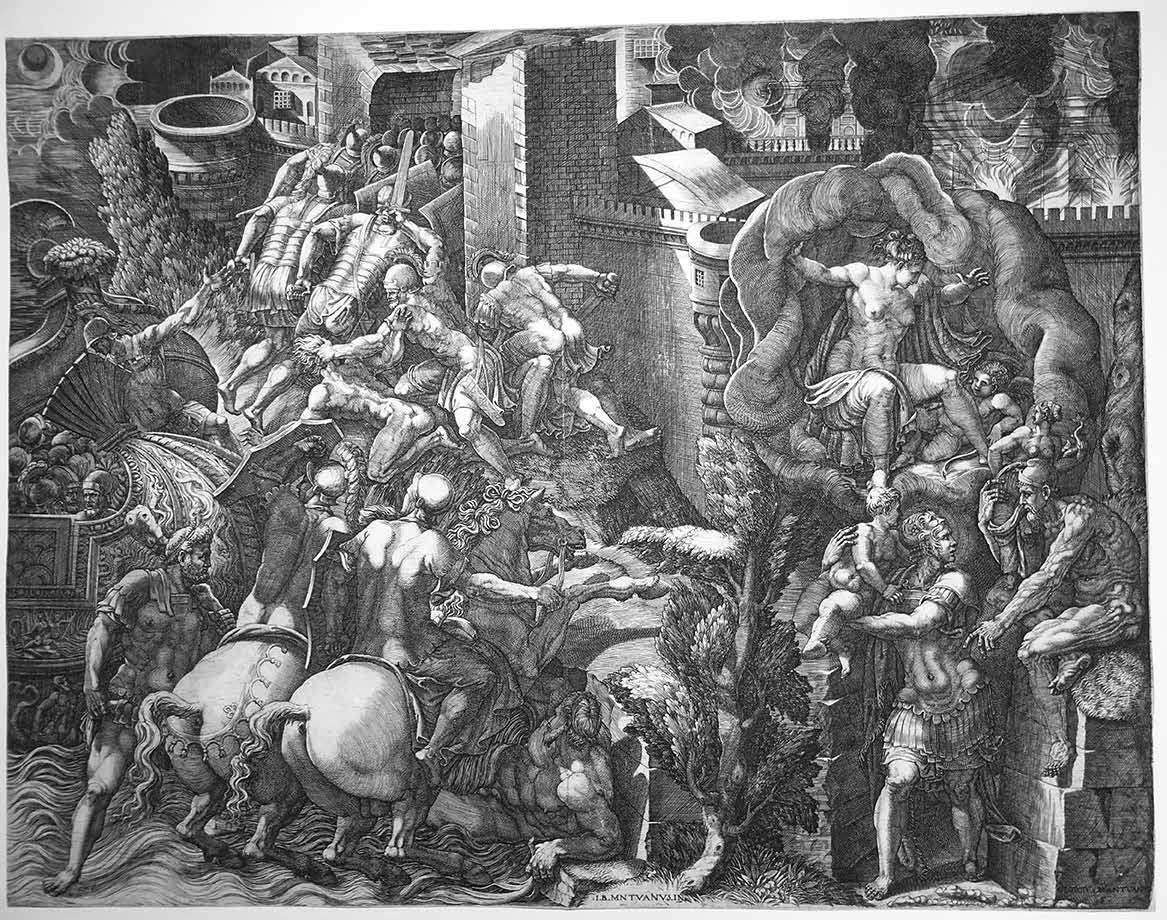

Immediately afterwards, in the next room, the audience has a chance to admire the engraving considered Sculptori’s masterpiece, displayed alongside his matrix: it is the very excited Naval Battle of 1538, on loan from the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica in Rome, a work perhaps of mythological inspiration (it could be an idea derived from the events of the Argonauts or from the clashes of the Trojan War), and praised by Gian Paolo Lomazzo, who extolled the “serious admirable intelligence in such a composition.” Often recalled by contemporary sources, the Naval Battle is one of the works of maximum commitment of the Bertani-Scultori pairing, a work with a complex and elaborate composition, the result of a skillful and articulate work on the planes, a clear expression of thathorror vacui that invades every Scultori print, where it is difficult to find a square millimeter that is not worked. It is perhaps the ultimate compendium of the elements that distinguish Scultori’s work on Bertani’s drawings: the nervous crowding, the harshness of the drawing, the almost violent chiaroscuro effects, the use of multiple vanishing points, and the negation of scientific Renaissance perspective, towards which Bertani had been polemical because he found it to be a mere geometric device, inasmuch as it was unable to offer a realistic translation of the binocular vision proper to human beings. The same characteristics, it will be noted, are discernible in Giorgio Ghisi’s prints with which the exhibition closes: tightrope walker compositions such as The Greek Sinon Deceives the Trojans, The Fall of Troy and, to a lesser extent, The Vision of Ezekiel and The Judgment of Paris, offer a useful measure of the legacy that Sculptori left to his younger colleague, who was able to initiate a similarly fruitful association with Bertani. In the finale, the exhibition bids farewell with a work by Diana Scultori, daughter of Giovanni Battista (a Deposition of Christ from the Cross) and a burin, Prisoners, traditionally attributed to Giovanni Battista but which because of its quality decidedly lower than his other works and for some formal divergences would perhaps be assigned to his son Adam, who continued his father’s activity but did not reach the heights touched by his parent.

The exhibition is accompanied by an in-depth catalog that takes stock of what is known today about the work of Giovanni Battista Scultori, presenting itself as an up-to-date and useful tool not only for getting to know his work, but also because it is able to offer a close look at the antiquarian culture of sixteenth-century Mantua, one of the salient themes of the exhibition at the Ducal Palace. Giovanni Battista Scultori. Intagliator di stampe e scultore eccellente is a curious, fine, intelligent, and rare exhibition that acquaints the public with one of the most fascinating of the many figures who worked in Mantua at the time of Giulio Romano and delves into a lively and animated context, a moment in history of great fortune for the Gonzaga court, a period during which what was conceived on the banks of the Mincio radiated elsewhere, in Italy and beyond: Mantua had become a thriving center of experimentation that also passed through the medium of printing. Indeed: the press was functional, writes Giorgio Marini in the catalog, to the “programmatic project of spreading and sharing Giulio’s [Romano’s] figurative inventions through all the declinations of ’drawing,’ contributing to making Mantua a new center of modern art.”

Finally, it will be worth noting two additional peculiarities of the Ducal Palace exhibition: on the one hand, the usefulness of a research exhibition, whose costs are, moreover, decidedly contained, and which continues along the direction given by the direction of Stefano L’Occaso, that is, expositive occasions aimed at delving into aspects and protagonists of the history of Mantuan art, according to a line that has already distinguished the museum’s offer for some years (only in the last year and a half should we remember the exhibition of the “Drawing”, which has been held in the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua).last year and a half, the exhibitions on Pisanello, Rubens, Grechetto and so on should be remembered), and which on this occasion has also led to lasting legacies that are not only immaterial, but also material, since Palazzo Ducale has purchased, again at a moderate expense, some important prints by Sculptors, which are part of the exhibition itinerary. On the other hand, the surprising ease with which the exhibition curated by L’Occaso demolishes the cliché that wants exhibitions of graphics to be less interesting than those of paintings or sculptures: the stereotype is overcome thanks to a narrative that never leaves the visitor alone, not even on a single piece, and that the audience will find not only thorough, but also lively, pleasant, tight, calibrated to a reasonable length of the visit and enhanced by a set-up akin to that of painting exhibitions, with the plates displayed as if they were paintings, impeccably lit, with the spaces properly managed. In short: research yes, but also able to speak to the general public. Those who work with graphic art should go and visit the Ducal Palace exhibition and take notes.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.