In one of his most recent books, L’hiver de la culture, Jean Clair recalled a visit to the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, in Paris, in the company of a young Canadian art historian, a museum curator, who was crossing the Atlantic for the first time: in that ancient temple, he was stunned by the mass that the sarcedote was officiating. For the young scholar, who had come from the frozen moors of Saskatchewan and who considered a building pulled up fifty years earlier to be ancient, it was not only a wonderful thing to be able to admire for the first time a monument that had been standing for centuries, but it was almost inconceivable to see that this temple was still intended for the function for which it had been created. The apologue is interesting because from Jean Clair’s lines, in this as in his other writings, there emerge flashes of that continuity between art and life that today’s culture industry often struggles to read, to interpret, to get across to the public. The history of art, Jean Clair wrote in his 1989 essay Méduse, is nothing other than the history of man, and the exhibition Inferno that opened last Oct. 15 at the Scuderie del Quirinale, curated by Jean Clair himself together with his wife Laura Bossi, surprises us, to a certain extent disorients us, upsets us and certainly strikes us, even with a certain violence, in part precisely because we are losing the habit of finding traces of this continuity and this history of art understood as a reflection of human history in spaces intended to host major exhibitions, and in part because at the Scuderie del Quirinale what is being staged is perhaps more than an exhibition.

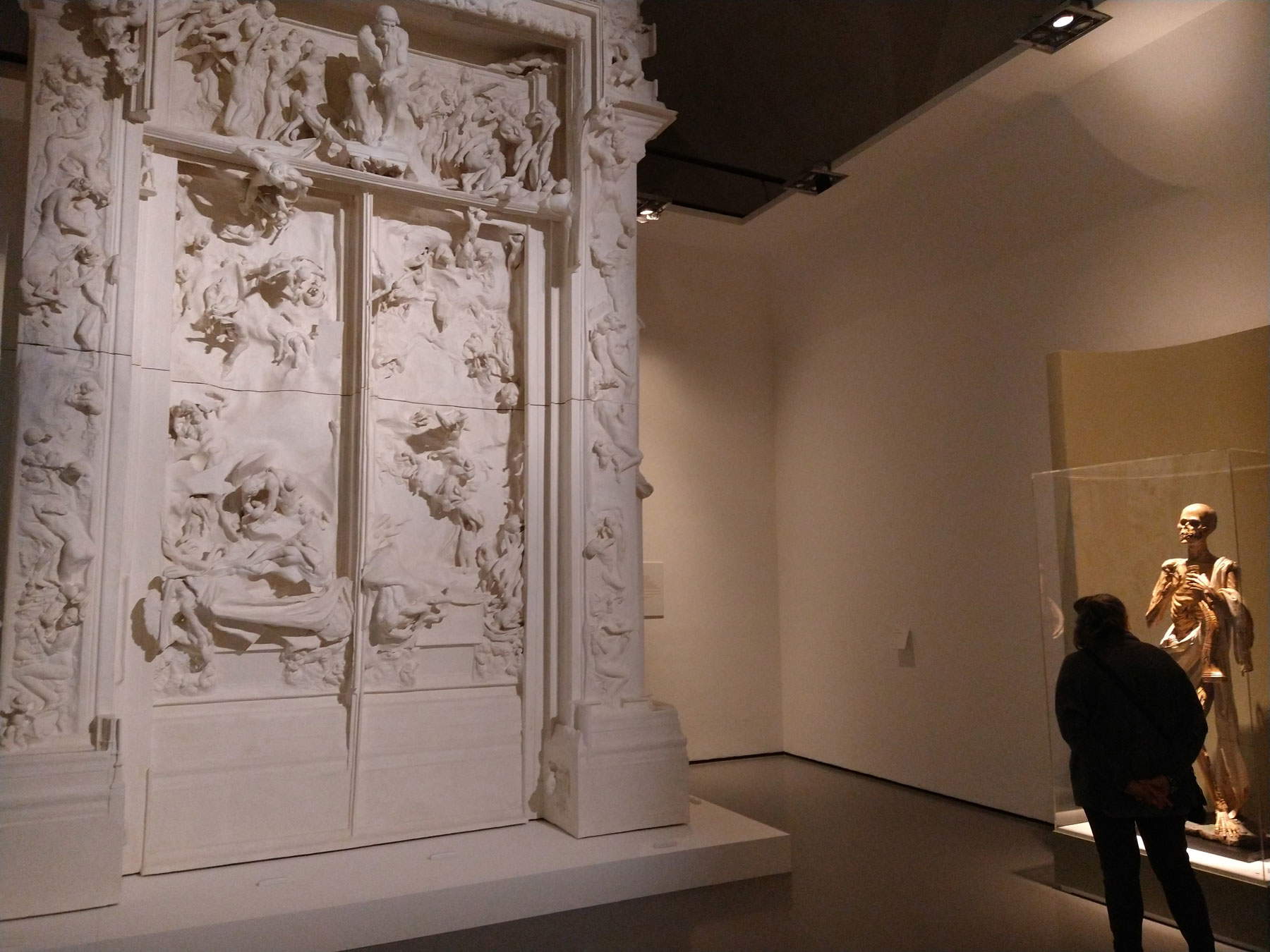

It is at once an exhibition, a play, a journey, even a conceptual artwork. It prescinds from any merely descriptive or illustrative logic (not least because it must be reiterated frankly: it would have made no sense to order yet another didactic exhibition on Dante’s Commedia in the year of the seven hundredth anniversary) and proceeds by refined juxtapositions, sometimes more obvious sometimes more daring, in a sumptuous crescendo, spectacular right from the choice of the works and their placement in the settings (it begins with a kind of introductory “limbo” and enters the exhibition by passing the life-size plaster cast of Rodin’s Gates of Hell, just to summarize the departure), reaching a finale that captures the audience with the same dramatic charge as the finale of a film.

And then it is an exhibition that is striking because it forces the audience to come to terms with the removed, if only for the duration of their stay at the Scuderie. One glimpses among the works the curator’s critical verve, which resurfaces from the pages of the catalog: “just as death no longer exists,” Jean Clair writes, “so evil no longer exists in the gaze of modern man. Believing that he has acquired a right to perpetual health, he believes himself potentially immortal. The corpse he leaves behind him is therefore no longer nothing. No longer anything that still concerns him, nothing for which he has any respect.” And again, “The total state we knew in the last century would be succeeded today by the total individual. And the cult of blood, which founded totalitarian society [...] would be succeeded by the cult of the excretory, in which the power of the total individual is affirmed. A civilization of a fecal nature, in which each individual believes that he no longer owes nothing to society but that he can, from it, demand everything.” What place can hell have in such a world? And what is hell? The descent into the abyss can begin.

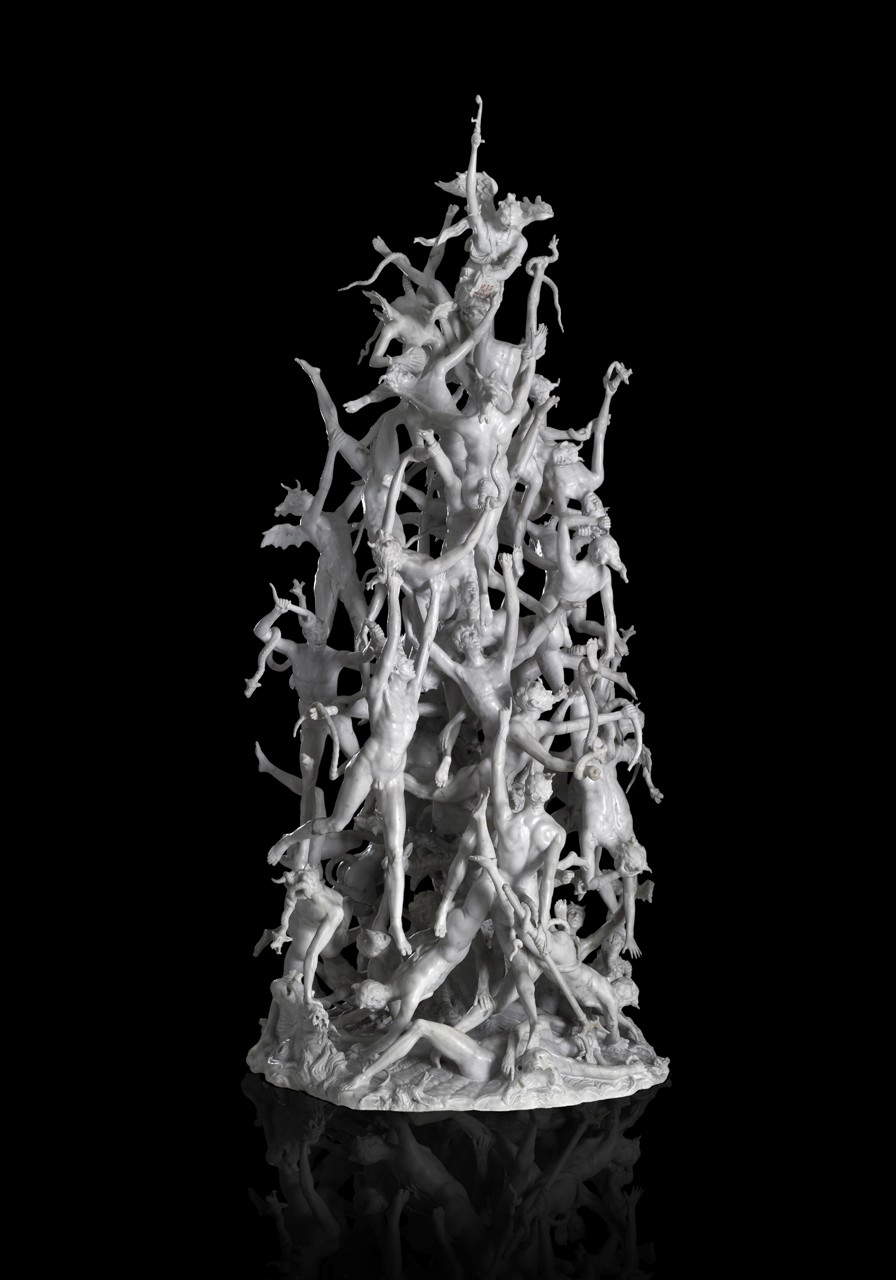

The beginning is, as mentioned, a kind of limbo that makes the premises clear and prepares the visitor for his journey: the antecedent, the fall of the rebellious angels, lives on in an astonishing comparison between Andrea Commodi’s The Fall, recently pulled out of the Uffizi storerooms and exhibited in the new sixteenth-century rooms, and the meticulous marble work attributed to Francesco Bertos (formerly given to Agostino Fasolato) from the collections of Palazzo Leoni Montanari in Vicenza, a dizzying pyramid of sixty figures carved from a single block of marble. The swarm of bodies twisting, clinging and falling, as much in Commodi’s paintings as in Venetian sculpture, visually recalls the gateway to Hell, which one arrives at after death and the Judgment, as we are reminded by the horrifying wooden sculpture by the Spaniard Gil de Ronza, a frightening life-size Death, and Beato Angelico’s Last Judgment, in a room that immediately shocks the audience with its strong scenographic impact.

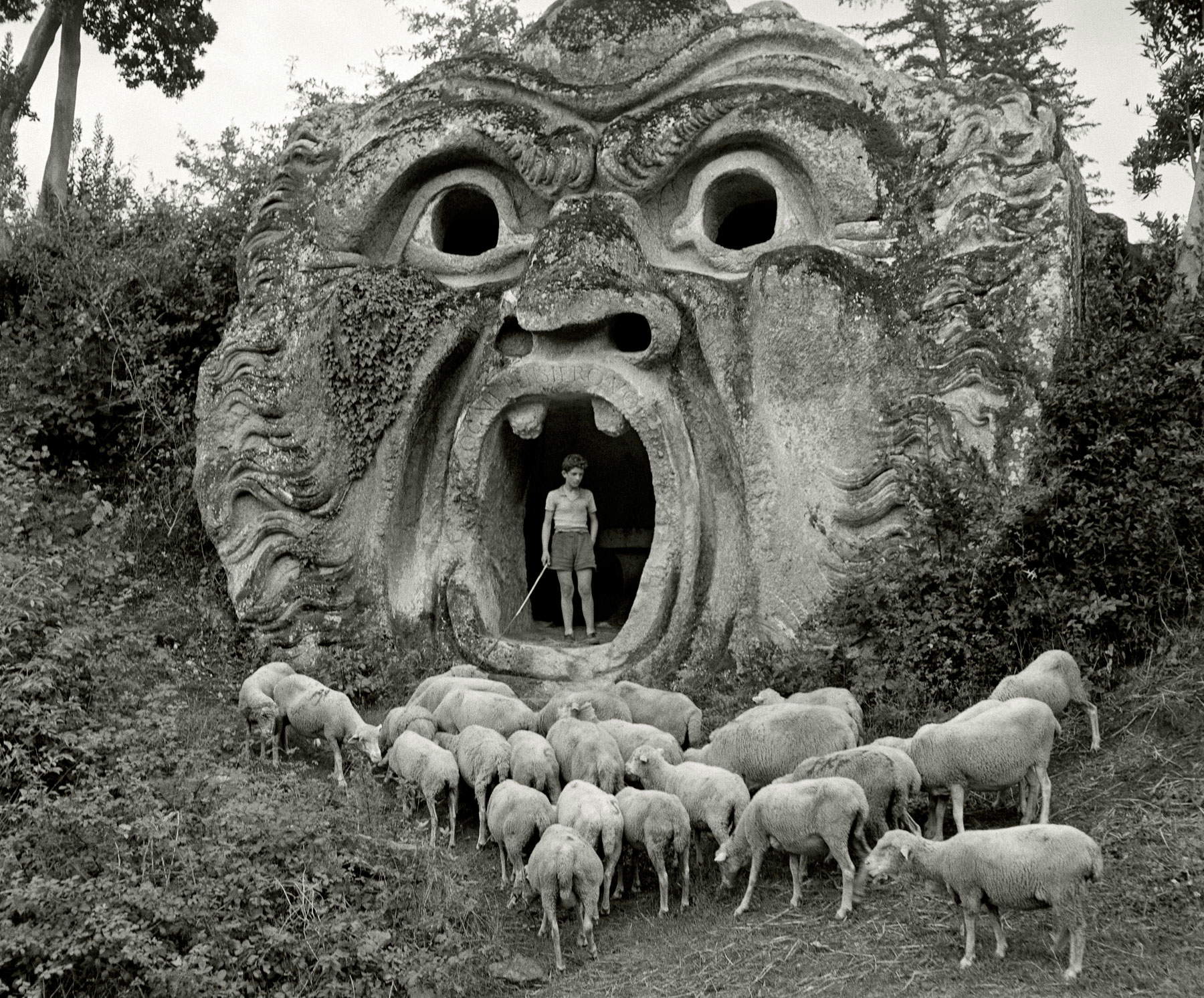

Crossing the threshold of the underworld, here is one of the earliest depictions of hell according to Jean Clair: a huge, gross mouth intent on engulfing teeming souls for eternity. “Hell,” writes the editor, “is an interminable gut, endless pit, ’puteus abyssi,’ ultimate latrine, full of unbearable odors, the fetid sewers in which the powers of hell are imprisoned and mortals who have rejected God are herded. In the second century, Tertullian, the first Church Father, will designate by the term ’puteus’ that infernal and gluttonous abyss, that ever-unfulfilled belly, that cavern teeming with monsters, that cave, that mouthful and anal antrum at the same time.” The “mouthful anthro” Jean Clair has in mind perhaps resembles the Orc of the Bosco di Bomarzo, featured in a 1949 photo by Herbert List, which is not so far removed from the monstrous animal that swallows souls in Jacob Isaacszoon Van Swanenburg’s painting, or to that species of dragon to which Christ opens his mouth, descending into limbo, in a keystone of the church of Saint Maurice de Vienne, which arrives in Rome translocated in a 1913 cast by Charles �?douard Pouzadoux: inside, souls stir that populate the hallucinated visions of Pieter Huys, of the Portuguese Anonymous who painted an Inferno where the damned boil inside large pots, or of Monsu Desiderio who imagines a kind of underworld dominated by Hades and Proserpine, with deep caverns framed, however, by classical architecture, filled with skeletons and souls wandering all over the place.

There is not only Dante’s hell, we learn openly from the exhibition: the hall of the “inhabitants of hell” is a kind of sampler of the imagination, it is a thicket of paintings whose authors were inspired by the most disparate sources, and which Laura Bossi summarizes well in her essay in the catalog: the blazing cavern of biblical texts, the strange land at the edge of the world that populates the visions of medieval monks (St. Brandanus imagined it crammed with buildings of the most unusual shapes and bizarre animals, and with a Judas who is tormented in the most sadistic and atrocious ways six days a week, while on Sundays, fortunately for him, he is allowed to rest), and of course the place of immense torture for the souls of damned sinners.

![Gil de Ronza, Muerte [La Morte] (1522 circa; legno policromo, 169 x 62 x 48 cm; Valladolid, Museo Nacional de Escultura, inv. CE0057)

Gil de Ronza, Muerte [La Morte] (1522 circa; legno policromo, 169 x 62 x 48 cm; Valladolid, Museo Nacional de Escultura, inv. CE0057)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/1802/gil-de-ronza-morte.jpg

)

![Auguste Rodin, La Porte de l�?Enfer [La porta dell�?Inferno] ([1880-1917], calco in gesso del 1989 in due parti, 298 x 399 x 122 cm parte bassa, 312 x 374 x 135 cm parte alta, altezza totale 610 cm; Parigi, Musée Rodin, inv. E33)

Auguste Rodin, La Porte de l�?Enfer [La porta dell�?Inferno] ([1880-1917], calco in gesso del 1989 in due parti, 298 x 399 x 122 cm parte bassa, 312 x 374 x 135 cm parte alta, altezza totale 610 cm; Parigi, Musée Rodin, inv. E33)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/1802/auguste-rodin-porta-inferno.jpg

)

There is a risk of déjà-vu in the sections that explore Dante’sInferno, because the pattern does not deviate much from that of other exhibitions held this year (above all the one in Forli): so here we are again seeing the illustrations of Federico Zuccari, of Giovanni Stradano, of William Blake, here again come the pains of Paolo and Francesca and those of Count Ugolino, here is theInferno of Filippo Napoletano, the portraits of Dante, starting with that, always unfailing, of Domenico Petarlini. It should be stressed, however, that the risk is well avoided, for several reasons: meanwhile, the keys to interpretation are different from what is expected. On the episode of Canto V, the curators have carefully avoided any hint of romanticism (except for a few episodes, such as the large canvas by Giuseppe Frascheri where the two lovers even manage to hold hands, or the usual Ary Scheffer who had already been seen at the San Domenico Museums), because Paolo and Francesca are first and foremost two souls burning in the infernal flames (see Henri-Jean-Guillaume Martin’s Paolo and Francesca aux enfers, assuming one can get to grips with the very bad lighting that, unfortunately, prevents an undisturbed view: an eventuality that is unfortunately not so sporadic in the exhibition), and which are swept away by the same storm that torments thousands of other sinners who have given themselves over to carnal pleasures in life: Victor Prouvé’s Voluptueux erase all remnants of sentimentality and plunge us back into that dimension of carnality, filthiness and low instincts on which Jean Clair and Bossi have built the scaffolding of their exhibition, from the moment the mouth of hell sucked us into its whirlpool. The same is true of Ugolino della Gherardesca: no pity, no reference to the character’s inner suffering and his troubled personal story. There is no Diotti’s Ugolino, locked up in the Torre della Muda meditating on his dreadful fate; there are not even Reynolds’ moaning and pleading children before a mute and impassive Ugolino (however much the Englishman’s work is the one that sanctions the beginning of Dante’s modern fortunes): at the Scuderie del Quirinale there is only the bestial image of a man stuck in ice, who with inhuman ferocity devours and flays the bloody head of his adversary, even going so far as to provoke, in Gustave Courtois’s painting, the dismay of a terrified Dante, who hides behind a seraphic adolescent Virgil.

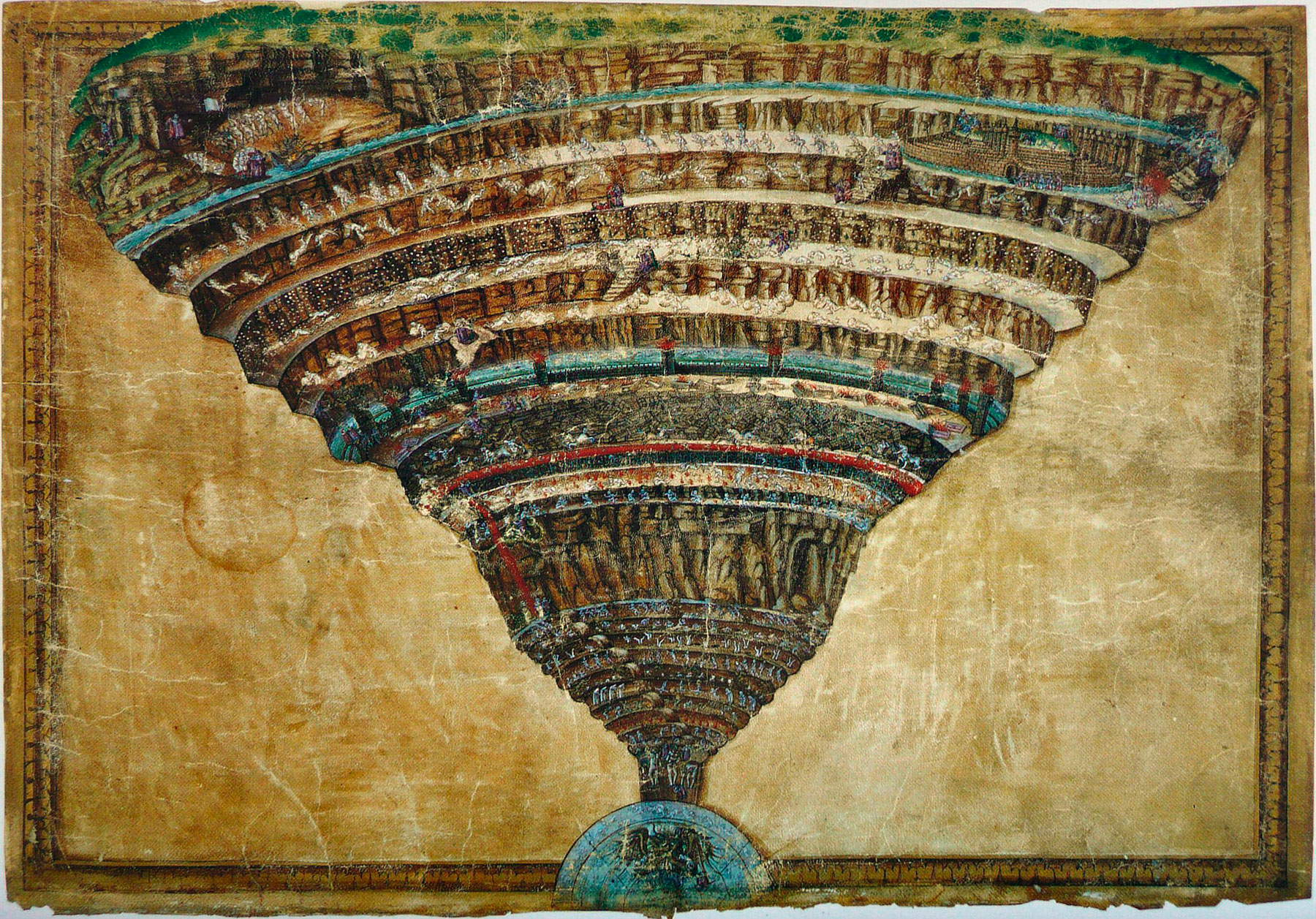

The section on Dante, apparently the most obvious one in the exhibition, however, has other features of originality. There is, meanwhile, the focus on the topography of hell, which opens with the exceptional loan of Botticelli’s Infernal Abyss, arriving from the Vatican Library, and continues up to the bizarre (and unsubstantiated, but nonetheless somewhat fascinating) theory of Roland Krischel, author in 2010 of an extensive essay in which he advanced the hypothesis that the Anatomical Theater of Padua was inspired by the inverted cone shape of hell, and that Galileo Galilei played a role in its design. “Imagined as a communal sojourn of the shadows or souls of the dead, then as a place of justice in the Afterlife,” writes Laura Bossi, “Hell is ’unthinkable, unspeakable, infigurable’ ... but human thought is irrevocably anchored in space, and poets have never given up ’spatializing’ the fate of the soul, describing the indescribable, imagining the afterlife as a ’place,’ endowed with a geography, a topography and an architecture.” There is a succession of images in the fastest section of the Roman review that try to measure hell, to reconstruct its hydrography, to hypothesize its more or less verisimilar locations. And then, another reason for interest are the illustrations of the Divine Comedy by Miquel Barceló, which sit well alongside the various Zuccari, Stradano, Blake, Doré and others, testifying, with their polite but not restrained expressionism, to the suggestions that Dante’s imagery still exerts today: “it is one of the great masterpieces of all time,” Barceló recounted two years ago in an interview in the pages of Finestre Sull’Arte on paper, “it is an incredibly current work: just change the names of the characters to find many photographs of current events. It is impressive how such an ancient poem manages to keep its topicality intact.”

![Gustave Doré, Virgile et Dante dans le neuvième cercle de l�?Enfer [Virgilio e Dante nel nono girone dell�?Inferno] (1861; olio su tela, 315 x 450 cm; Bourg-en-Bresse, Centre des Monuments Nationaux �? Musée du Monastère Royal de Brou, inv. 982.234)

Gustave Doré, Virgile et Dante dans le neuvième cercle de l�?Enfer [Virgilio e Dante nel nono girone dell�?Inferno] (1861; olio su tela, 315 x 450 cm; Bourg-en-Bresse, Centre des Monuments Nationaux �? Musée du Monastère Royal de Brou, inv. 982.234)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/1802/gustave-dore-ix-girone.jpg

)

Ascending to the upper floor, after an interlocutory section on the hells of popular culture, one traces the history of the representation of the devil, from the demonic being of the earliest centuries to the fallen angel of the Romantics and Symbolists, and that of his manifestation on earth, the temptation, which takes on the most disparate guises trying to seduce or frighten St. Anthony, now with the terrifying monsters of Salvator Rosa’s Temptations, one of the most hallucinatory texts of the entire seventeenth century, arriving from the Pinacoteca Rambaldi di Coldirodi in San Remo, now with the devils armed with clubs of Bernardo Parentino, or with the uninhibited and procreative temptress of Cézanne’s singular canvas arriving on loan from the Musée d’Orsay. No one believes in the devil today, however, Jean Clair sentences. “The Church itself no longer dares to name him, just as it no longer dares to speak of Evils or Hell.” Today we have more to fear from human hells than from the devil: and so the great hall of hells on earth opens, the apotheosis of horror.

Evil is part of human history. For those who believe, the first man born to a human couple is a guy who murdered his brother. And, as the panels in the hall inform us, although the images multiplying before our eyes are entirely self-explanatory, in modern society evil has also updated. It has taken, meanwhile, the form of prisons that resemble factories and factories that resemble prisons: Piranesi’s intricate and dark prisons parade next to Pierre Paulus’s gloomy smokestacks and Anders Montan’s huge steel mills, all the way to the dark meanders of a great industrial city overlooking the sea, Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse’s, where a man mourns the death of poetry while in the distance trains run on the rails, the air fills with the fumes of funnels, shacks thicken at the edge of the metropolis. It is the hell on earth of alienating labor that has turned humans into slaves. On the adjoining wall is the hell of the last, of the outcasts, corresponding to the poor patients of psychiatric hospitals painted by Signorini and drawn by Paul Richer, again with a reference in the work of contemporary Spanish artist David Nebreda to the theme of the unclean, which is perhaps the most subtle leitmotif of the exhibition. On the opposite side of the room, here instead is the hell of migrants, represented by a distressing canvas by Previati(Gli orrori della guerra: l’esodo, executed while the First World War was raging), who in a painting unusual for his production does not hesitate to thrust before the viewer’s face one of the saddest and most tragic consequences for those who managed to escape the massacres. The entire center of the great hall on the upper floor is occupied by the darkest and bleakest visions of war, the “most bestial madness,” according to Leonardo da Vinci’s definition, that has never ceased to haunt humanity. One almost feels a sense of suffocation in front of the battered corpses and skeletons abandoned in the trenches of World War I, in Otto Dix’s engravings all placed side by side. One would like to attempt to escape when standing before the casts of soldiers wounded in that same conflict, who almost seem to be watching us. One is awed when one sees one of the engravings in Percy Delf Smith’s The Dance of Death series, Death is Stunned, where the harvester herself is incredulous at the carnage caused by the folly of human beings. It is disconcerting to see how much the battlefield painted by Georges Leroux in his work L’enfer resembles the apocalyptic visions of the painters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries downstairs: only this is not a vision, it is reality.

And then, just when you think you have touched the climax of the exhibition, comes the worst hell that ever appeared on earth, that of the Nazi death camps. One reads the original draft of Primo Levi’s If This is a Man and looks at the canvases of another deportee, Zoran Mušič, before turning to see the most terrible of the visions on display: Fritz Koelle’s Dachau Memorial, a bronze depicting a survivor of Nazi hell caught with a distressed expression as he points to the relative the corpse of a child he holds in his arms, opposite the massacre of Le petit camp à Buchenwald by Boris Taslitzky, an artist who knew Buchenwald firsthand, as he was interned there in 1944. “If I go to hell, I will make drawings of it,” Taslitzky had this to say. “After all, I have experienced it. I’ve been there before, and I’ve drawn.” There is nothing more to add. Or maybe there is: the last two disturbing images, Raymond Mason’s Twin Towers Ablaze and Nein! Eleven by the Chapman brothers prove that hell is not yet free of us, and that we have nothing to rest easy about.

![Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse, La mort de la pourpre [La morte della porpora] (1914 circa; olio su tela, 219 x 298 cm; Musée d�?arts de Nantes, inv. 203)

Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse, La mort de la pourpre [La morte della porpora] (1914 circa; olio su tela, 219 x 298 cm; Musée d�?arts de Nantes, inv. 203)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/1802/georges-antoine-rochegross-morte-porpora.jpg

)

![Georges Leroux, L�?Enfer [L�?Inferno] (1921; olio su tela, 114,3 x 161,2 cm; Londra, The Imperial War Museum, inv. IWM ART)

Georges Leroux, L�?Enfer [L�?Inferno] (1921; olio su tela, 114,3 x 161,2 cm; Londra, The Imperial War Museum, inv. IWM ART)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/1802/georges-leroux-l-enfer.jpg

)

![Percy Delf Smith, The Dance of Death: Death awed [La Danza della Morte: La Morte è sbalordita] (1919; acquaforte e puntasecca su carta, 275 x 332 mm; Londra, The Imperial War Museum, inv. IWM ART 16640-2)

Percy Delf Smith, The Dance of Death: Death awed [La Danza della Morte: La Morte è sbalordita] (1919; acquaforte e puntasecca su carta, 275 x 332 mm; Londra, The Imperial War Museum, inv. IWM ART 16640-2)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/1802/percy-smith-morte-sbalordita.jpg

)

![Boris Taslitzky, Le petit camp à Buchenwald [Piccolo campo a Buchenwald] (1945; olio su tela, 300 x 500 cm; Parigi, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d�?art moderne �? Centre de création industrielle, inv. AM 2743 P)

Boris Taslitzky, Le petit camp à Buchenwald [Piccolo campo a Buchenwald] (1945; olio su tela, 300 x 500 cm; Parigi, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d�?art moderne �? Centre de création industrielle, inv. AM 2743 P)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/1802/boris-taszlitzky-buchenwald.jpg

)

![Gerhard Richter, Sternbild (Constellation) [Costellazione] (1969; olio su tela, 200 x 150,4 cm; Londra, Ben Brown Fine Arts, inv. RIC00059)

Gerhard Richter, Sternbild (Constellation) [Costellazione] (1969; olio su tela, 200 x 150,4 cm; Londra, Ben Brown Fine Arts, inv. RIC00059)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/1802/gerhard-richter-sternbild.jpg

)

We can, however, look up: the ascent to “see the stars again,” with the works of two great contemporaries, Anselm Kiefer and Gerhard Richter, closing the path after having descended into the deepest abyss as in a sort of Dantean journey that, however, has little of the unreal and imaginative about the ending, is hope for liberation and rebirth, to use the pair of nouns that Matteo Lafranconi uses in his essay on the exit from hell. Almost as if, after making us spend two hours touching the worst of human beings, the curators want to offer us a chance for redemption. We move from the unclean to the “world” in the original meaning of the term, the mundus “figure of order and beauty,” which has the same valence as the Greek cosmos. Like Dante, at the end of the exhibition we have ascended. Hell, however, has not stopped: it continues behind us. As much as faith and religions may be in crisis, hell is a reality that remains well present on earth: those images that troubled us are there attesting to it. And they have troubled us precisely because the history of art is the history of man.

Jean Clair has already publicly declared that Inferno will be his last exhibition: this concludes his career as a curator, with the realization of a project he has long chased and longed for. Perhaps it will not be the most scientific exhibition of recent times (however, this is not its purpose), some will say that it will not even be the most necessary exhibition, but perhaps we are not far from the truth if we affirm that it is the most powerful and the most visionary of those that have been seen in Italy in at least the last ten years. Inferno transcends the very concept of “exhibition.” It is a catabasis that has the structure of Dante’s journey (how many exhibitions manage to be so engaging?), it is also an itinerary in the curator’s mind, and it is above all a drama that describes humanity by relying solely on the power of images, which in turn become a mirror of the “hedonistic, pragmatic, or traditionalist, or positivist, or progressive society” that is today’s society, because a society as pragmatic as ours cannot be anything other than a society that is reduced to its organic elements, to pure matter, to the domain of pure biology. Our hell is no longer that of Dante’s bolge and circles, it has simply changed its appearance.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.