In what different places and in how many different ways can silence be depicted in a painting? In fact, silences are not all the same: there is the silence of domestic quiet, there is the silence of contemplation, the silence of anticipation of a joyful event and the silence of waiting that heralds something dramatic, there is the silence of melancholy and loneliness, the silence of the night. There is silence in an interior and silence in a landscape, whether natural or urban. Silences that are felt and perceived within a painting in quite different ways, through the presence or absence of a human figure, through expressions or through colors.

Peculiar and perhaps unique is the way of painting silence and emptiness of a Danish painter, Vilhelm Hammershøi (Copenhagen, 1864 - 1916), active between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, who in his lifetime was one of the greatest great Danish painters of his time, famous not only in Northern Europe but also in many European countries, but who then experienced, outside his homeland, long decades of oblivion, roughly from shortly after his death until the 1980s, and who has now only recently, in the modern era, been rediscovered, both on the market and in terms of exhibitions. In recent years there have been exhibitions in Barcelona, London, Munich, Paris, and Krakow. The last important presences in Italy date back to the Venice Biennales of 1903 and 1932 and to the Rome International Exhibition of 1911; it is therefore due to the sensitivity of curator Paolo Bolpagni that he has now brought back to Italy a selection of this painter’s Nordic atmospheres on display in Rovigo, at Palazzo Roverella.

A total of fourteen out of eighty-four of the entire exhibition are Hammershøi’s works featured in Hammershøi and the Painters of Silence between Northern Europe and Italy, this is the title of the current exhibition in Rovigo, and just being able to admire them brought together in a single location is worth the visit, considering also that in Italy there is preserved only one work by the artist, a 1913 self-portrait donated in 1920 to the Uffizi Galleries by his wife Ida (which unfortunately was not brought to the exhibition), and that to see those on display here one would normally have to travel to Hamburg, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Odense or Paris. However, the writer would have preferred to be able to see an even wider selection of Hammershøi’s paintings, including more of his typical interiors, such as Interior. Strandgade 30 from the Städel Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Interior with Woman at the Piano, Strandgade 30 from a private collection, or Sunbeams or Sunlight. Grains of Dust Dancing in the Sunbeams from the Ordrupgaard in Charlottenlund, and some portraits such as Portrait of a Young Woman, which is none other than Anna, the artist’s sister, and Interior with Young Man Reading (Svend Hammershøi), both housed at the Hirschsprung Samling in Copenhagen, shrinking perhaps the last section devoted to silent landscapes made during the years Hammershøi lived, in the late 19th and early 1920s, by French, Belgian and Italian artists.

In contrast, one has the pleasure of admiring his first figure-free Interiør of 1888 entitled The White Door (Interior with Old Stove), in which an open white door forms the transition from a dimly lit room with a stove to a light-filled corridor overlooked by another white door, in this case closed; a transition therefore from shadow to light, which is, however, a dim,Nordic light. Also on display is the famous Hvile (Rest) of 1905, which has been in the Musée d’Orsay ’s collections since 1996: the painting, which depicts his wife with her back turned sitting on a chair, her hair up, the nape of her neck uncovered, and her blouse blending in with the color of the wall toward which the woman is facing, in contrast to the white of the flower-shaped receptacle in the center of the cabinet that stands next to the portrayed subject, was among thirteen canvases from the collection of Alfred Bramsen, a collector and devoted supporter of the artist, with whom Hammershøi participated remotely in the1911 International Exhibition in Rome. He was among the ten winners of the first prize and was awarded ten thousand liras. And again, there is an opportunity to admire Hammershøi’s only painting of an Italian subject , now in the Kunstmuseum Brandts in Odense, which is a view of the interior of the basilica of Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, a church of early Christian origin on the Caelian Hill characterized by a central plan with architraved Ionic columns supporting the tiburium. Hammershøi and his wife Ida left for Rome in October 1902.It is known that the artist was primarily attracted to ancient architecture, while he paid little attention to Raphael, Michelangelo, and works from the Baroque period. He was struck by Santo Stefano Rotondo and, after obtaining permission to work inside the basilica and after studying the framing in a pencil drawing now preserved at the Pierpont Morgan Library, he began painting, deciding to abandon the frontal view for a side viewpoint, shifted to the right, with four columns in the foreground. The light here is, remarkably, warm and soft.

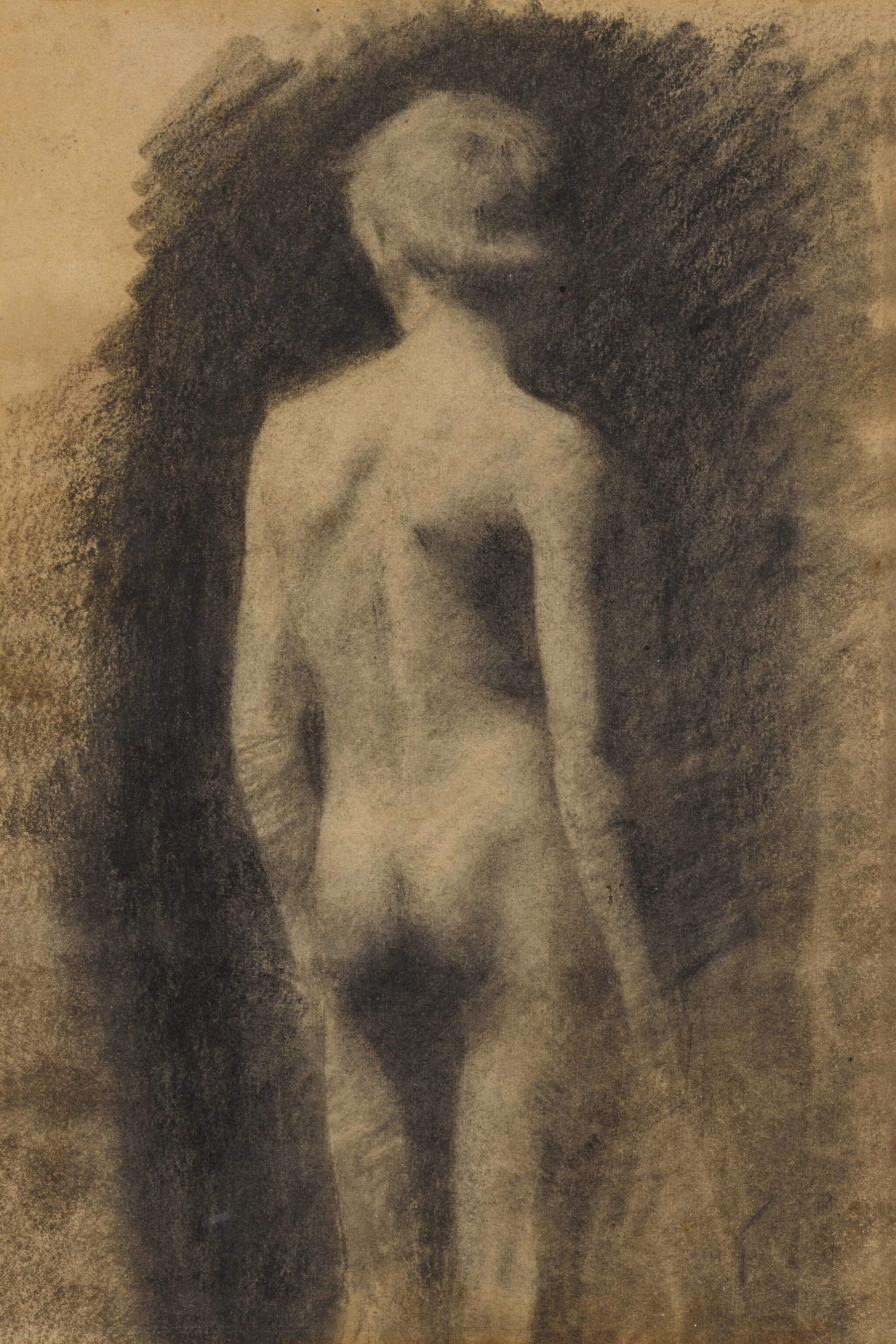

But let’s go in order. The exhibition kicks off with a section devoted to Hammershøi’s education : the Charcoal Study of Male Nude Seen from Behind that opens the section and the exhibition is probably the result of lessons at the Independent Study School for Artists that the young Hammershøi began attending after the long-establishedRoyal DanishAcademy of Fine Arts. It should be noted, however, how his approach to drawing actually dates back to the tender age age of eight, and how his early education in art was financed especially by his mother Frederikke, who had him taught drawing and painting lessons by some of the big names in the Danish art scene of the time, including Niels Christian Kierkegaard, cousin of the famous philosopher and pupil of Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, who as an important exponent of Neoclassicism had left in his heirs a particular predilection for the study of the nude but with the use of real, living models. Indeed, Vilhelm came from an upper middle-class and cultured family, so he was fortunate enough to cultivate and indulge his artistic endowment without any kind of financial problems, both privately and at important institutions. And while at the Royal Academy he received a more traditional approach, at the Independent Study School he also had the opportunity to engage with an art that looked outside Denmark, especially to France and Paris: His teachers included Peder Severin Krøyer, among the leading exponents of the Skagen School, a kind of Scandinavian declension of French Impressionism but without the fragmentation of color into small brushstrokes; among the elements dear to Krøyer was precisely the motif of the ray of light coming in through the window and passing through the composition, as found in many of Hammershøi’s works. Returning to the Study of a Nude Seen from Behind, the drawing reveals Vilhelm’s ability to depict a youthful body realistically but at the same time retaining the fragility of youth; it is also noteworthy how the theme of the subject being portrayed from behind appears early on, which will be found often in his production, especially those devoted to interiors with people, where the person is almost always his wife Ida. Another important influence Hammershøi had in his training, thanks to a trip at the age of twenty-three to the Netherlands and Belgium, was his direct acquaintance with and study of Dutch and Flemish seventeenth-century painters and the nineteenth-century Hague School characterized by genre painting with an intimist approach and domestic subjects, with women intent on reading, sewing, and playing musical instruments (figures also dear to Hammershøi’s heart), and by restrained colors. Here in this section, for example, are works by Gerard ter Borch, Johan Hendrik Weissenbruch, Bernard Blommers, and Jan Jacob Schenkel, all of whom share a common theme of depicting interiors with people intent on their activities. There is also a large painting, with a tree in the foreground, by Vilhelm’s younger brother Svend, who also became a painter but unlike his brother also a ceramist: what is noticeable, however, is the predominant color scheme, almost a monochrome with brown and gray tones.

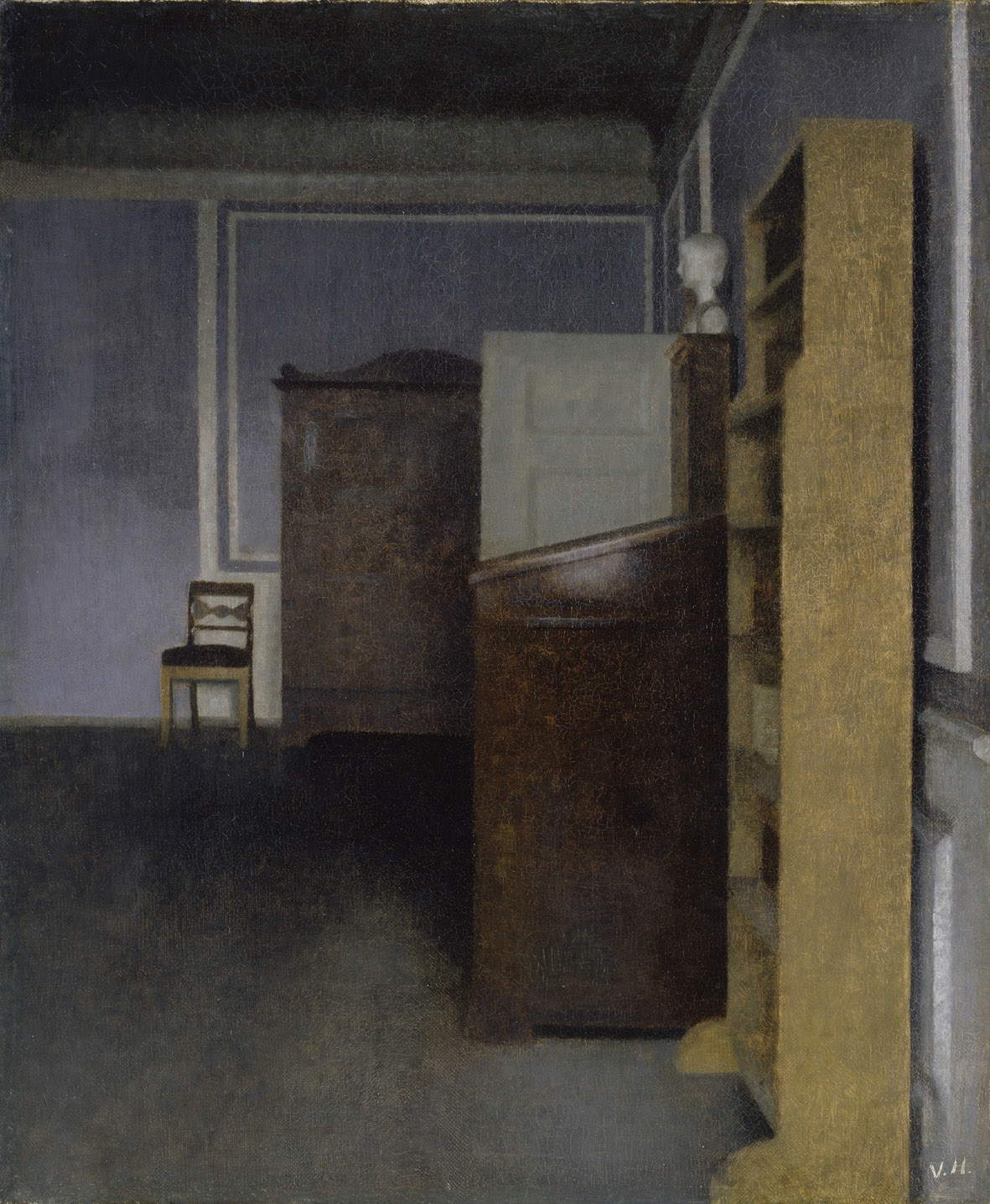

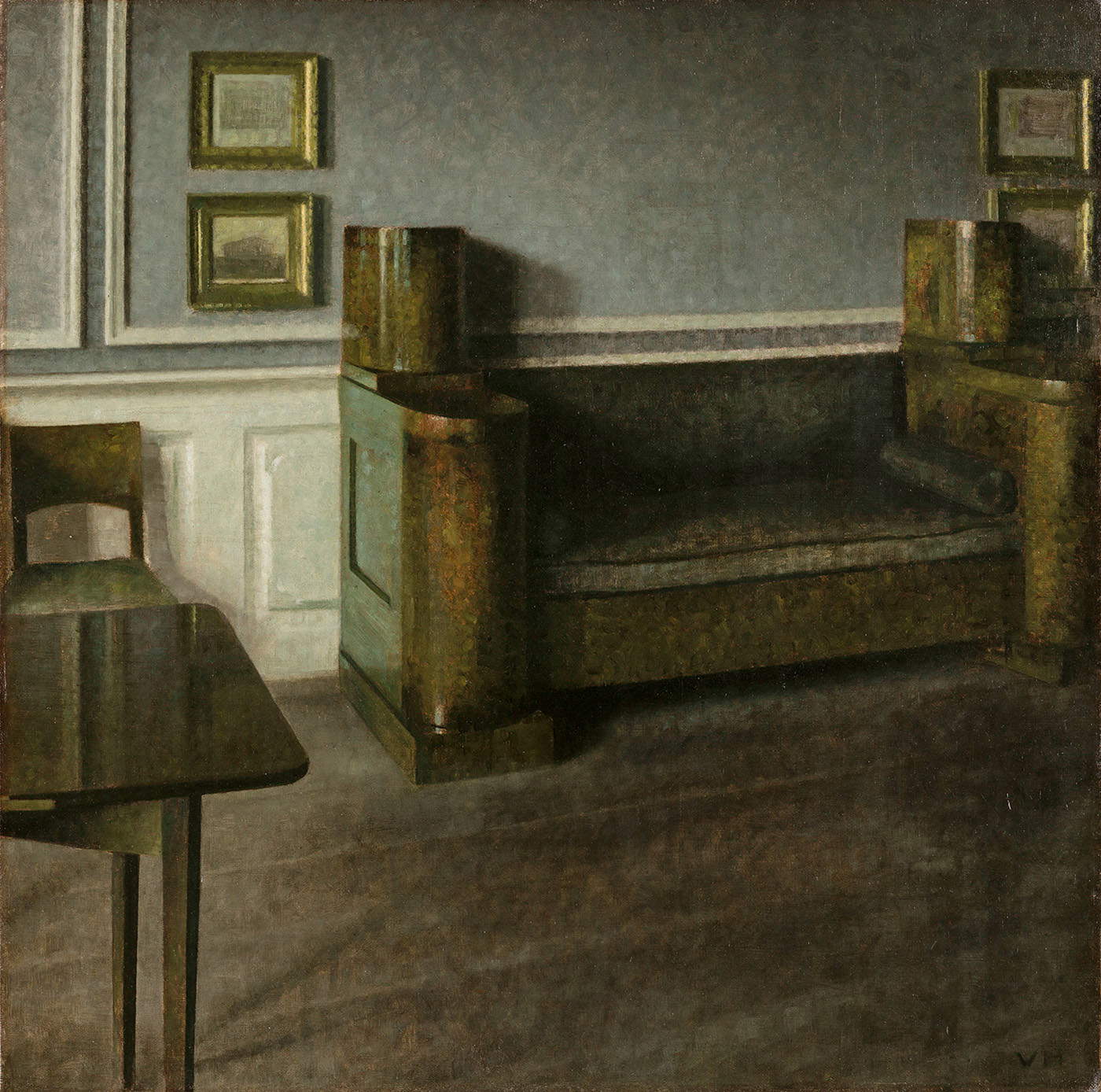

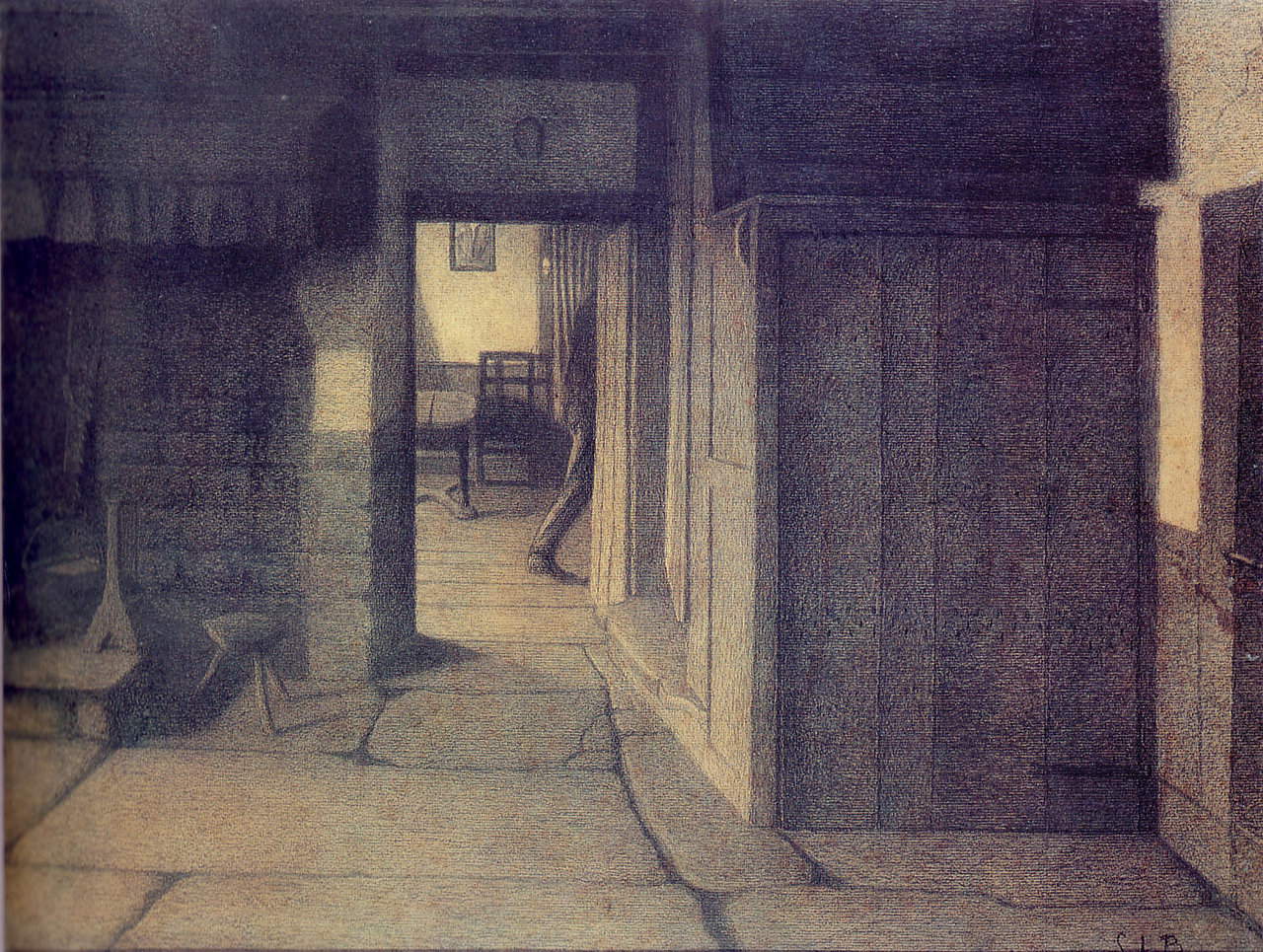

We continue with domestic interiors without human presences depicted by Hammershøi, including the aforementioned first of his Interiør, The White Door, and Sunlight in Living Room III, in which the dim brightness of the Northern European sun shyly filters through a window into the interior of the room, creating slight shadows and shading, but without making that window visible (only its shape reflected on the wall can be seen). The interiors depicted in Sunlight in the Drawing Room III, as in Interior, Strandgade 30, and as in most of his interior scenes that would also appear in his production with figures, are those of the apartment at street number 30 on Strandgade, one of the main streets in the Christianshavn district of Copenhagen, where Vilhelm and Ida lived from 1898 to 1909. These are works in which the lines of the bare walls, the essential furnishings, a sofa and lonely chairs leaning against the walls, the glimpses of bias creating geometries between a bookcase, a cabinet, a door, a closet, and a bust, render, as Bolpagni writes, “the small bourgeois world of Hammershøi, which lingers on fragments of the ordinary, where unexpected beauty lurks, and which, in a philosophical ’eulogy of absence,’ has chosen to ’cultivate its own garden,’ finding there everything it needs,” denoting at the same time careful attention to what the artist himself called ’the architectural character of the picture. In an interview with the Danish magazine Hver 8. Dag given in 1907, Hammershøi stated, ’What makes me choose a subject is often its lines. And then, of course, the light, which matters a lot. But it is the lines that I love most.’ Hammershøi’s three interiors are compared here with the two interiors depicted by the Frenchman Charles-Marie Dulac (Paris, 1865 - 1898) and the Belgian Georges Le Brun (Verviers, 1873 - Stuivekenskerke, 1914), in which, while focusing on essential elements of furniture, there is an entirely different light in one case and a meticulous rendering of details in the other. It is in this section, moreover, that the Danish painter’s interior scenes are compared through two videos on floor structures to scenes from Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film Gertrud (1964), as parallels were noted between the framing, compositional patterns and suspended atmospheres of the paintings and the film.

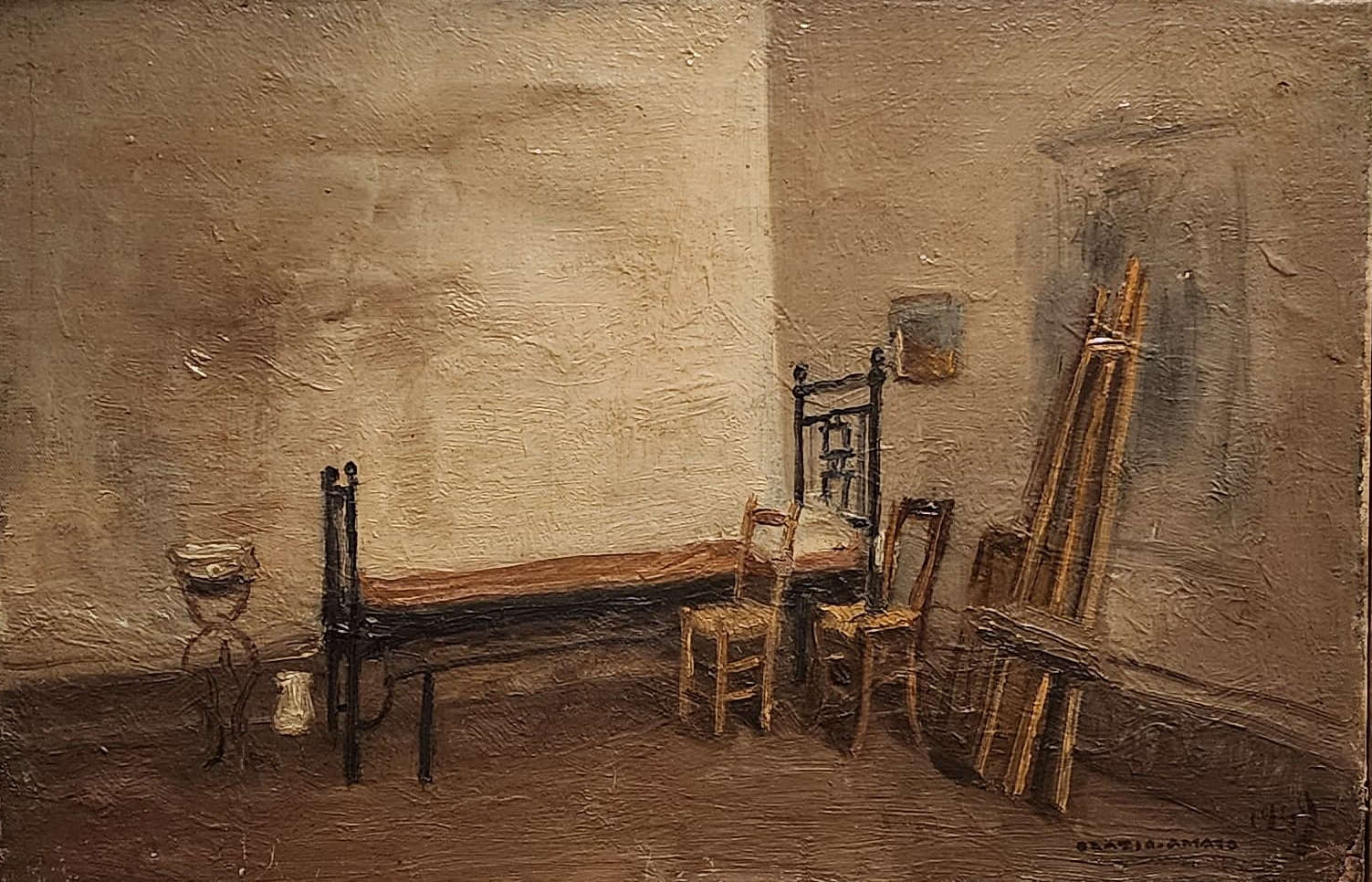

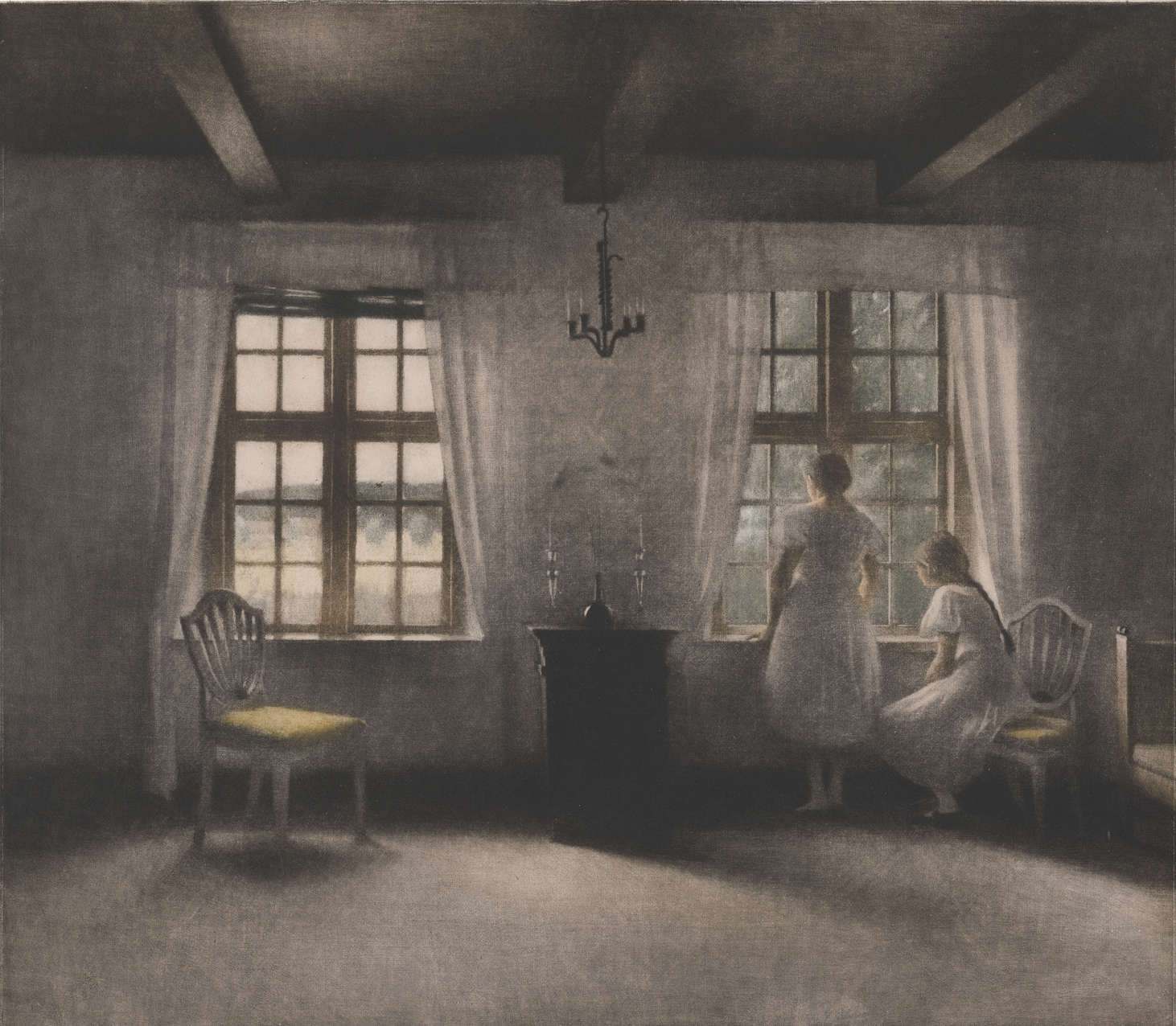

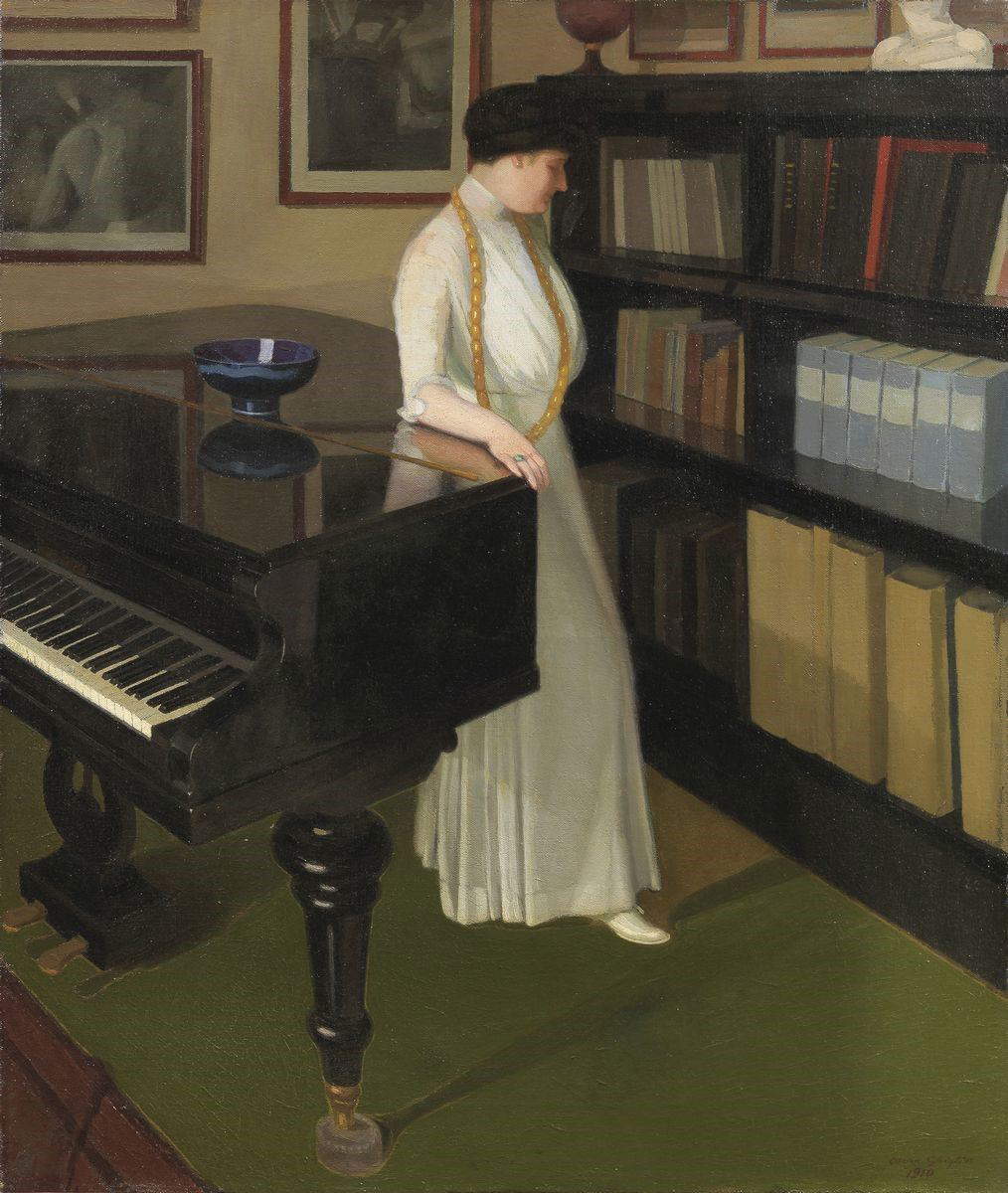

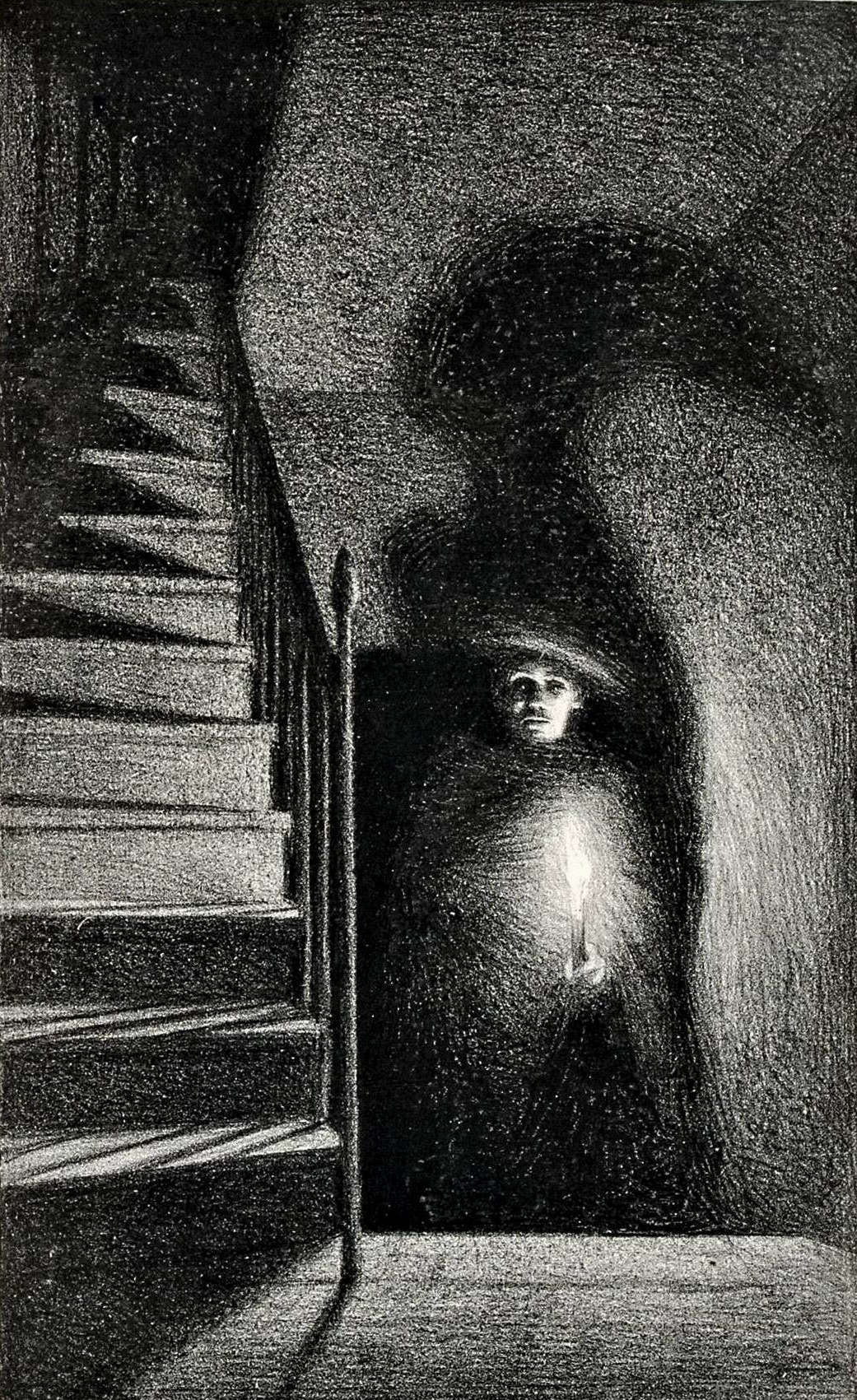

One wondered at first how many different ways silence can be depicted in a painting. The immediately following section, inevitably linked to the one just described, seems to provide an answer, and it is also among the stated objectives of the exhibition “to identify, through comparisons between his paintings and those of other artists of his contemporaries and the next generation, a poetics that places the theme of silence at the center.” As already mentioned, Hammershøi’s is a poetics of emptiness and light, where emptiness is not nothingness, but the absence of people, and where there are people, it is the absence of action, of gestures, to leave room for silence, stillness, eliminating any narrative aspect, and where the light is never a symptom of a calm and terse atmosphere, but suffused, tending to melancholy, which, if anything, is a symptom of an uneasy atmosphere emanating from an apparent calm. Here, then, his 1907 Interior with Couch is placed on this occasion in comparison with those painters who in Denmark, but also in Italy and the Franco-Belgian area, were inspired by him: there follows theInterior with a comfortable atmosphere and warm light by Carl Holsøe (Aarhus, 1863 - Rome, 1952), his friend and fellow Academy student; the flamboyant work of Henri-Eugène Le Sidaner (Port Louis, 1862 - Paris, 1939), the works of Giuseppe Ar (Lucera, 1898 - Naples, 1956), the Italian closest to Hammershøi’s compositions because of the presence of doors and windows that are often white, but illuminated by a warm light that expresses tranquil domesticity, the melancholy and resigned interior of Orazio Amato (Anticoli Corrado, 1884 - Rome, 1952) and the evocative convent of Sant’Anna in Orvieto by Umberto Prencipe (Naples, 1879 - Rome, 1962); and again, the eerie interior of Xavier Mellery (Laken, 1845 - Brussels, 1921) and the oppressive interior of a mill by Charles Mertens (Antwerp, 1865 - Calverley, 1919). Comparisons continue in the next section, devoted to interiors with figures, with artists all coeval with him: Hammershøi’s two paintings, which see in one case a woman reading and in the other a woman sweeping the floor (here there is a clear reference to Dutch and Flemish art but with a whole different atmosphere, as there is no the sense of expectation and suspension for possible secret anguish as in those of the Dane), are compared with Carl Holsøe’s Solitude and Woman with Fruit Bowl, with Waiting for Guests by his friend and brother-in-law Peter Vilhelm Ilsted (Sakskøbing, 1861 - Copenhagen, 1933), with Mrs. Ojetti at the Piano by Oscar Ghiglia (Livorno, 1876 - Prato, 1945) in which we note the shadows on the dress and bookcase and the reflections on the polished surface of the piano, the nocturnal and eerie atmosphere of the engraving Light and Shadows by Swedish Symbolist Tyra Kleen (Stockholm, 1874 - 1951) compared with a nocturnal interior by Hammershøi, and the mysterious Man Passing by Georges Le Brun.

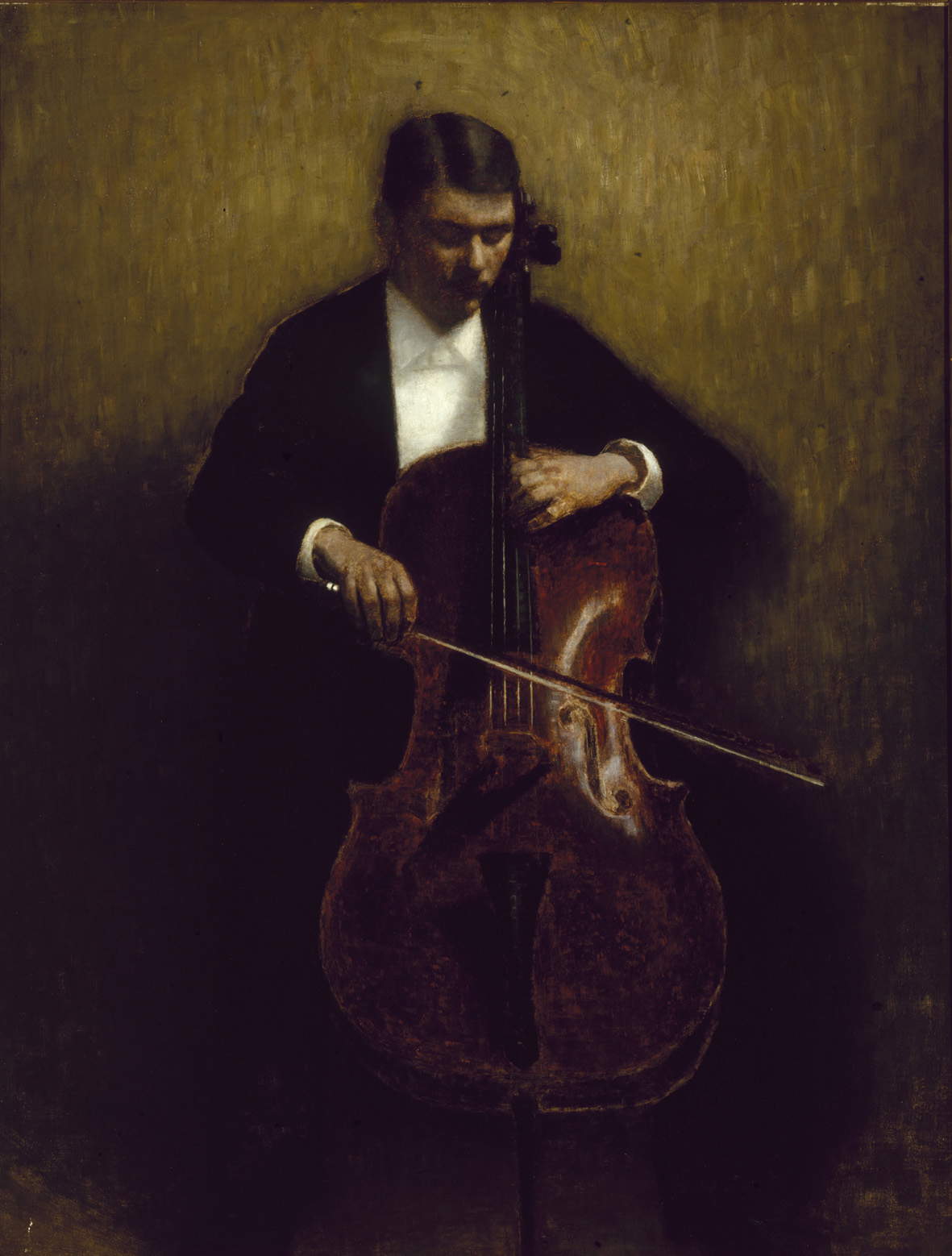

From interiors to portraits: Hammershøi was opposed to portraying commissioned subjects, as he thought that a portrait presupposed close knowledge of the person to be portrayed, so his portraits were limited to his mother, wife, sister, brother and close friends. Here his wife Ida Ilsted is portrayed in no fewer than three paintings, namely the frontal portrait of the then still engaged woman, characterized by the young woman’s absent, dreamy gaze and a jacket whose color blends into the background(Rainer Maria Rilke was so impressed by this work exhibited in 1904 in Düsseldorf that he decided to go to Copenhagen to meet the artist), the aforementioned Hvile (Rest) flanked by Oscar Ghiglia’s portrait of his wife from behind as she plays the piano, and the Double portrait of the artist and his wife seen through a mirror, exemplifying the theme of incommunicability. Added to these is only the portrait of Henry Bramsen, the cellist son of his friend, collector and patron Alfred. It would have been nice to have been able to admire in this section the portrait of his sister Anna and Interior with young man reading (Svend Hammershøi), but we instead move forward from now on into the silence of the landscape, beginning with Hammershøi’s aforementioned only painting of an Italian subject and continuing with the depiction of the city. His last work in the exhibition is in fact the depiction of Christiansborg Palace, one of Copenhagen’s most famous buildings, immersed in a muffled atmosphere, without any human presence and with a dominant light tending to gray, then, as written by the curator, “the discourse broadens to deserted urban views, desolate nocturnes, ’landscapes of the soul,’ and ’dead cities,’ which had such good fortune in France, Belgium and Italy during the years Hammershøi lived there: a further declination of the elusive and enigmatic, subtly anguished feeling that we find in his production.” The choice was thus to broaden the concept of silence, in the opinion of the writer sometimes even forcing its boundaries a little, to include works that reflect more on the themes of emptiness and silence rather than on the particular vision of Hammershøi, the painter to whom the exhibition is dedicated. There is the Bruges of Fernand Knopff and Henri-Eugène Le Sidaner, the evening visions of Émile-René Ménard, the rooftops of Paris by Charles Lacoste or the Jardin du Luxembourg by Eugène Grasset, William Degouve de Nuncques’ nocturnal Venice, Umberto Prencipe’s engravings, and a series of urban and maritime views of The Hague and Antwerp by Vittore Grubicy de Dragon. And again, under the sign of Gabriele d’Annunzio’s Cities of Silence, there are nocturnes by Mario de Maria, Giuseppe Ugonia, Domenico Baccarini, and Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona. Concluding with the last section devoted to Silent Landscapes and other “artists of silence” who, between the late 19th century and the early 1920s, produced works “permeated by a melancholic and absorbed stillness.” Thus parading one after the other are Alphonse Osbert with his female figures immersed in the landscape, Charles-Marie Dulac with his mystical gleams, Giuseppe Ugonia with his Arcadian lithographs, Mario Reviglione with his crepuscular atmospheres, Umberto Moggioli with his meditations in solitary places, Giulio Aristide Sartorio with his architecture immersed in the green, the desolate countryside of Onorato Carlandi and Napoleone Parisani, and the views of Enrico Coleman and Pio Bottoni.

In the face of all this roundup of artists, the visitor’s gaze is perhaps at times diverted from what should be the main protagonist of the exhibition, given also that this is, as mentioned, the first major presence in Italy in the modern era of a nucleus of works by the Danish artist gathered together.

Well done is the catalog, which faithfully traces the exhibition with all the works present (however, individual works are missing), and devotes essays to the various aspects of Hammershøi’s poetics, from themes to places, female figures, the relationship with Italy and the fortunes of his art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.