by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 23/07/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Igor Hofbauer. Fuck Hof' in Carrara, Teké Gallery, from June 16 to July 30, 2017.

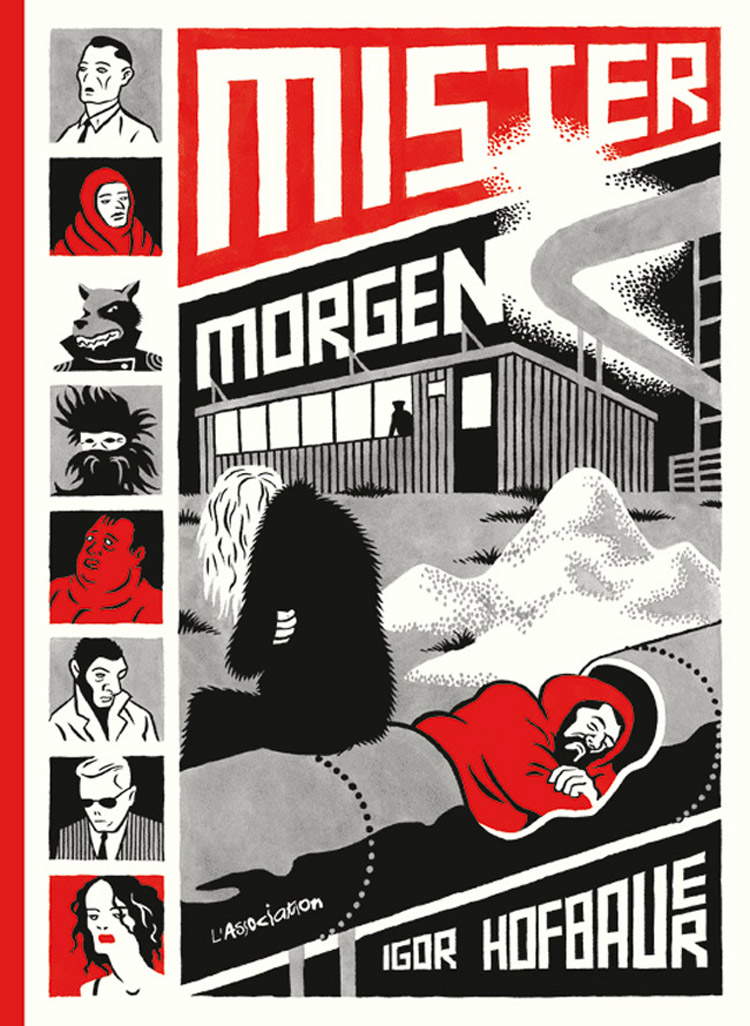

It must not have been an easy task for the curators of the Fuck Hof exhibition to sort through the endless production of Igor Hofbauer (Zagreb, 1974), a Croatian graphic designer and illustrator who is one of the leading figures of the contemporary underground scene and the author of a decidedly consistent body of work. It must not have been easy, also due to the fact that Hofbauer’s production always remains at a very high level: just take a look at his most recent works to realize this. In fact, Stefano Dazzi Dvořák, Marco Cirillo Pedri and Alessandra Ioalé (who are to be credited with having organized a comprehensive exhibition, covering more than twenty years of Igor Hofbauer’s career without omitting anything) have brought to Carrara, at the Teké Gallery, even the latest works of the Croatian artist. Comics, mostly: among the new works is Mister Morgen, a suffocating collection of short stories in which the stories of a diverse, desperate, downtrodden humanity with no hope or chance to improve its condition unravel through the outskirts of an Eastern European city, a kind of dark and empty Novi Zagreb, the “New Zagreb” of huge residential blocks built during the years of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, in full decadence, which takes on the burden of giving substance to the author’s fears and obsessions.

|

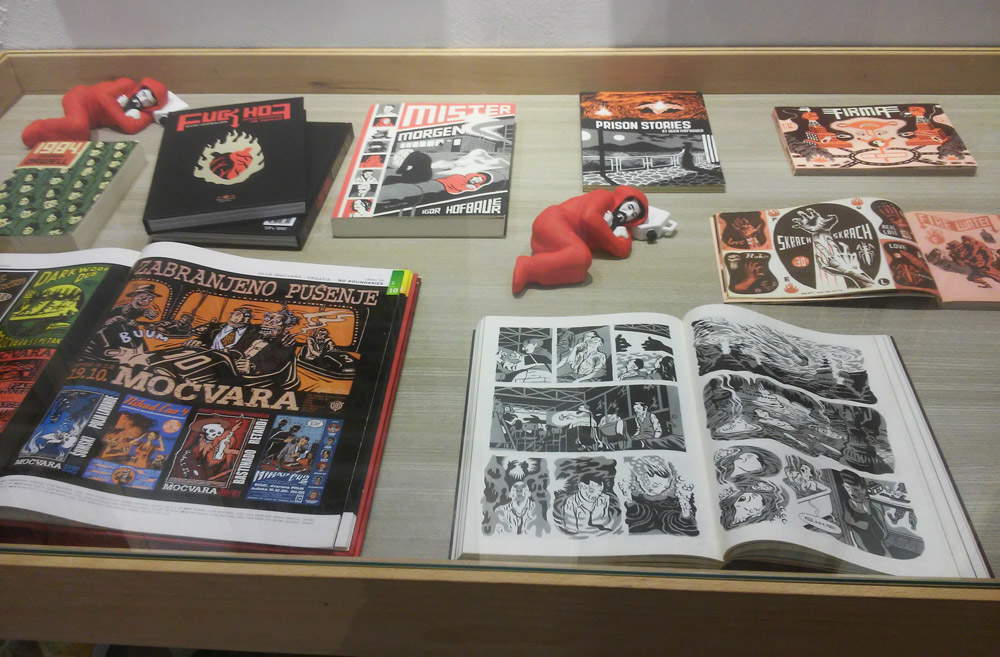

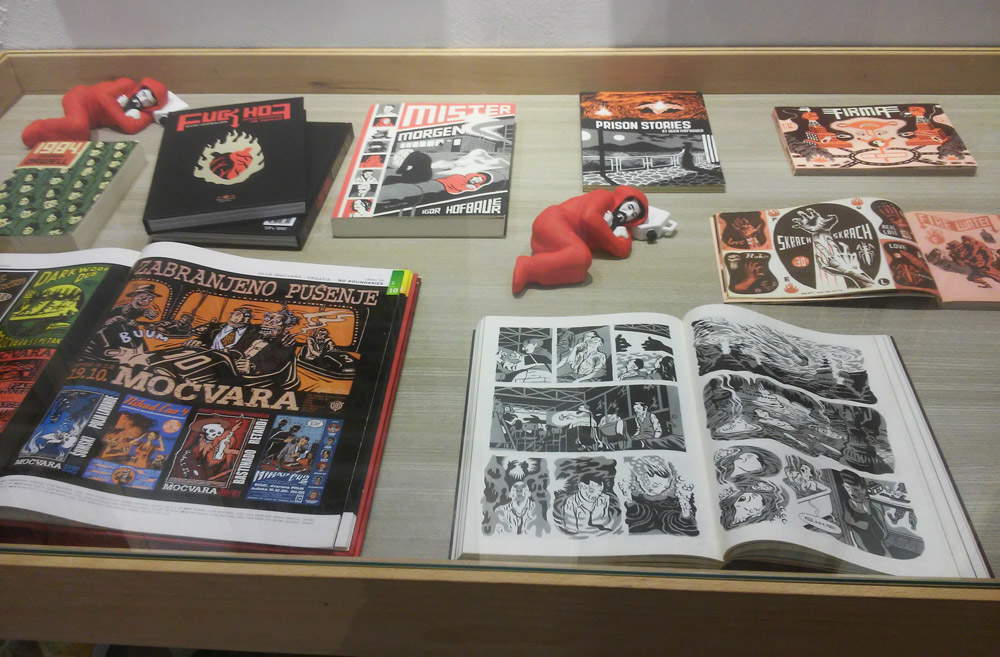

| One of the rooms of the exhibition Igor Hofbauer. Fuck Hof |

|

| Display case with some of Igor Hofbauer’s comics |

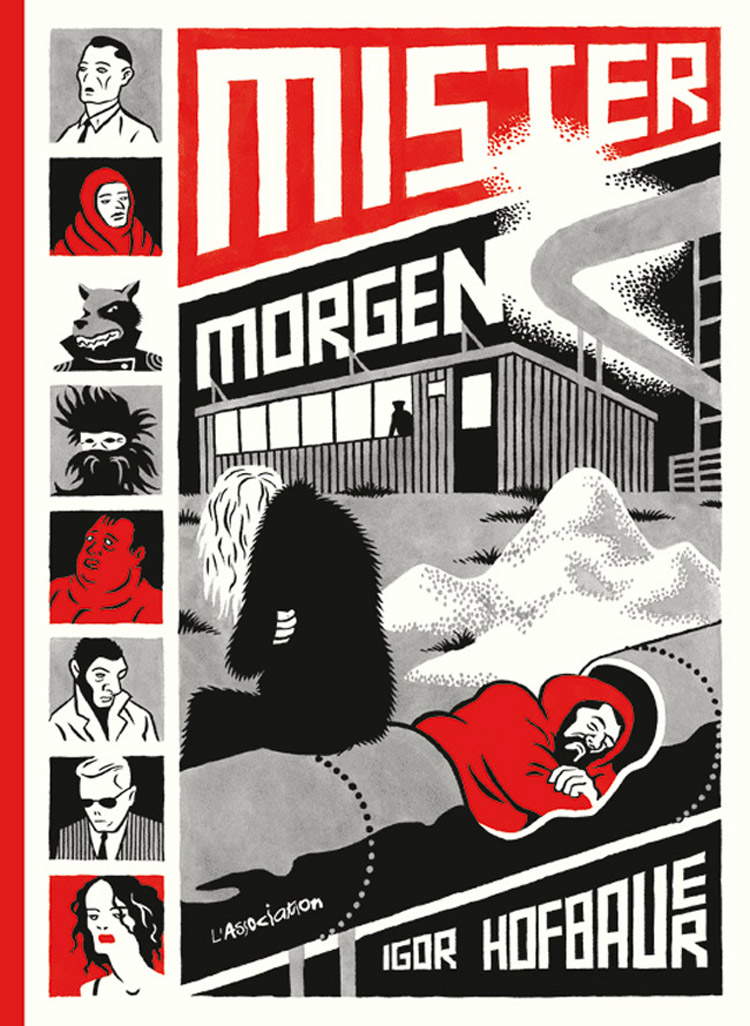

The fierce sarcasm is evident right from the title of the work, borrowed from the nickname of one of the most popular Croatian singers of the last century, Ivo Robić, also known as “Mister Morgen” because Morgen (“Tomorrow,” in German) was the title of his most successful song: an easy and light song with lyrics full of cheerfulness and optimism, published in an era (the piece dates back to 1959) marked by economic rise and confidence in the future. And paradoxically, the character in Hofbauer’s collection named after the book is a homeless man who shares his lot with other derelicts like him. Sense of oppression, mistrust and uncertainty emerge from the visionary atmospheres of Mister Morgen: a work that, writes Vittore Baroni in the exhibition catalog, “produces a departure from the norm, a total immersion in a universe of sociopathic delusions and erotic hallucinations, a litmus test of our Western society in full devolution. In this enigmatic dreamlike symphony, curiously nostalgic and pervaded by a vein of poetic horror, the reader is called upon to fill in the gaps, trying to ferret out the ghosts of a doomed civilization.”

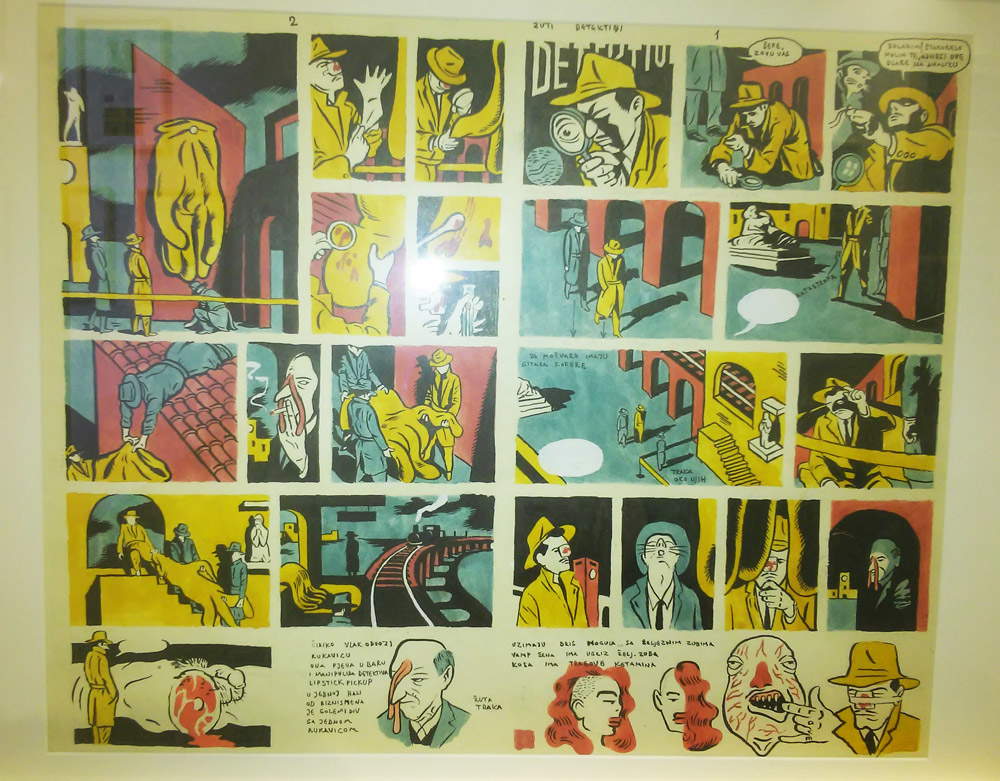

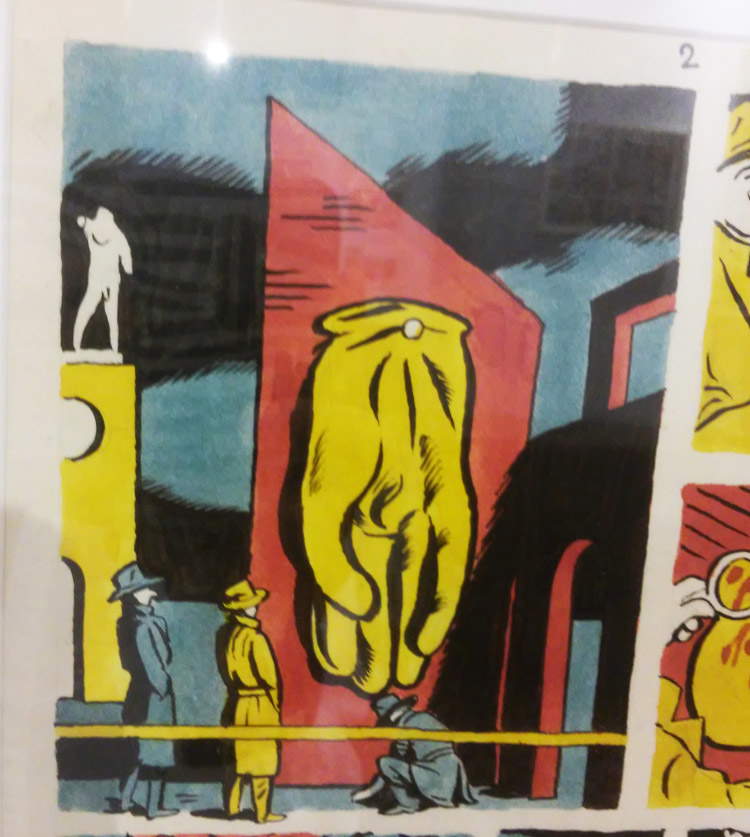

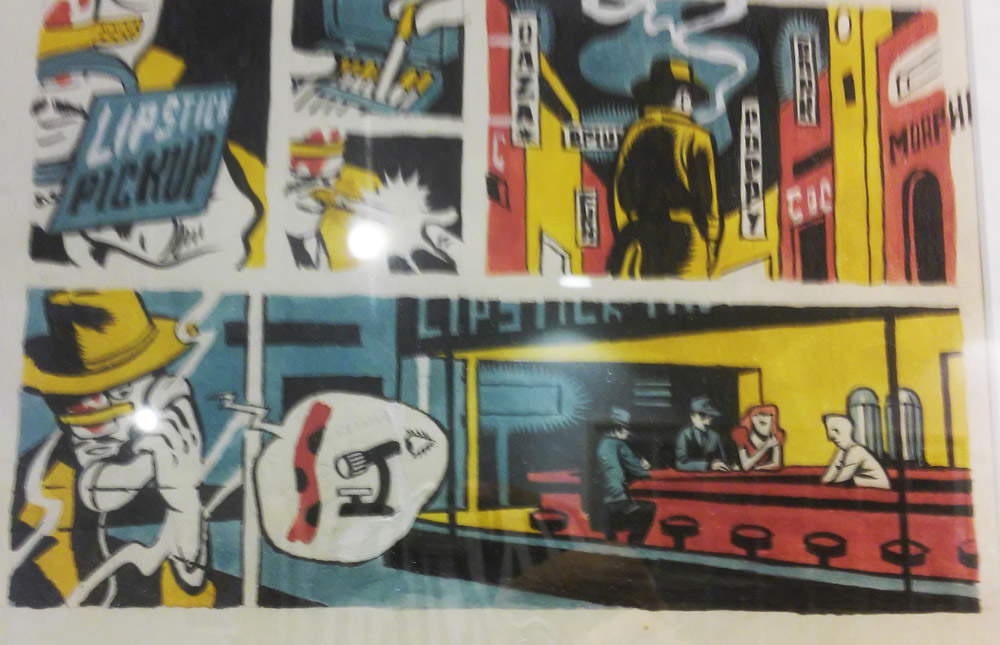

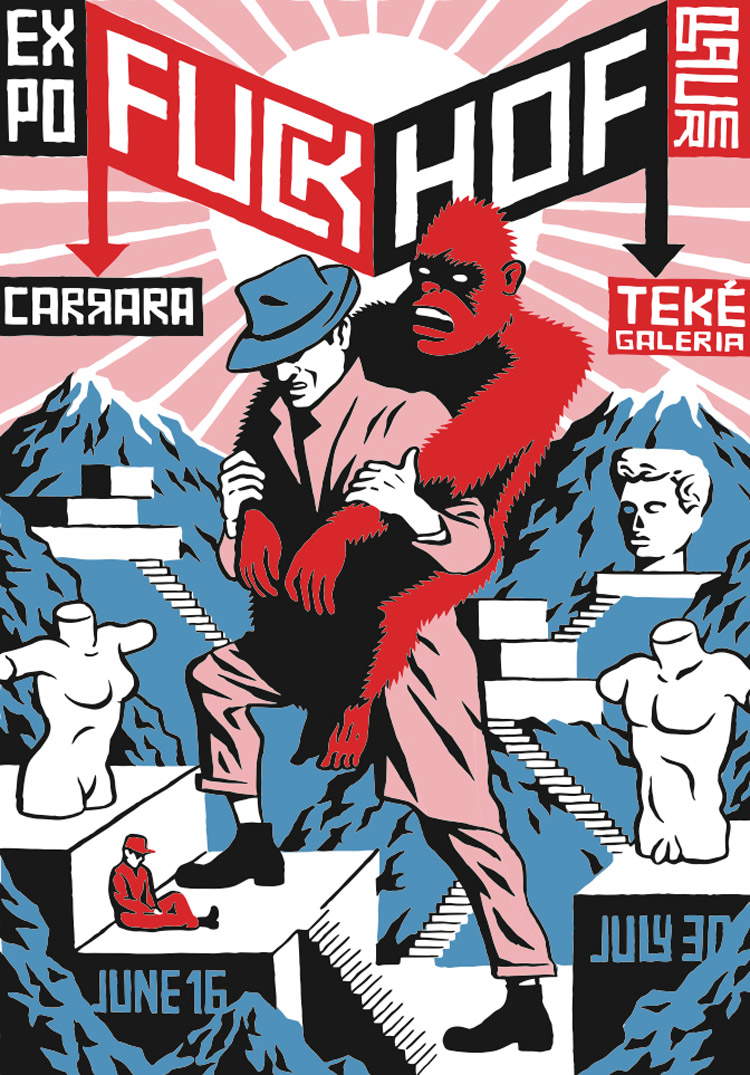

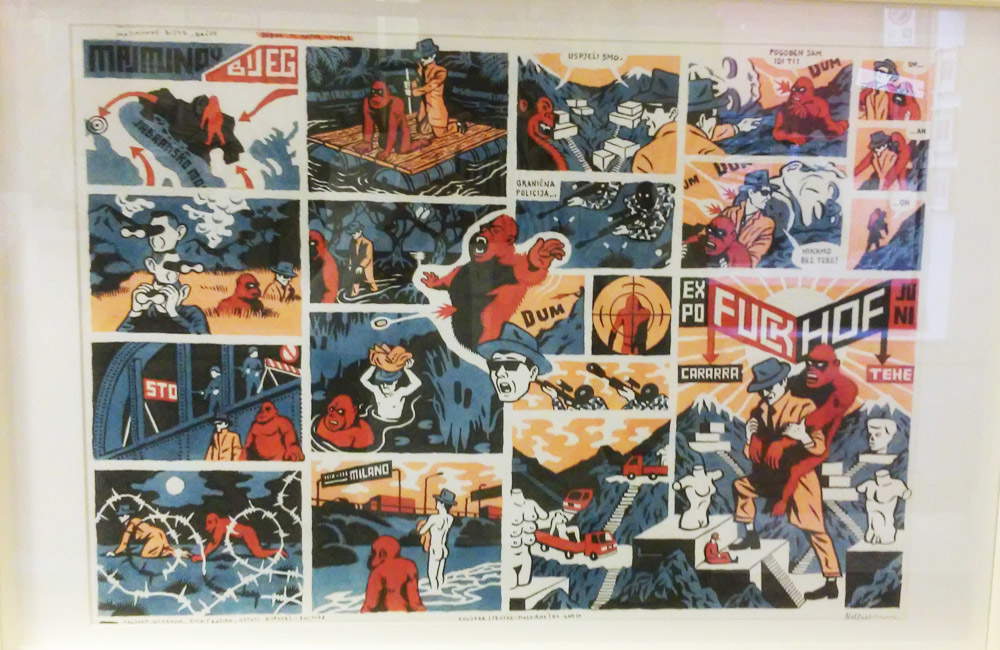

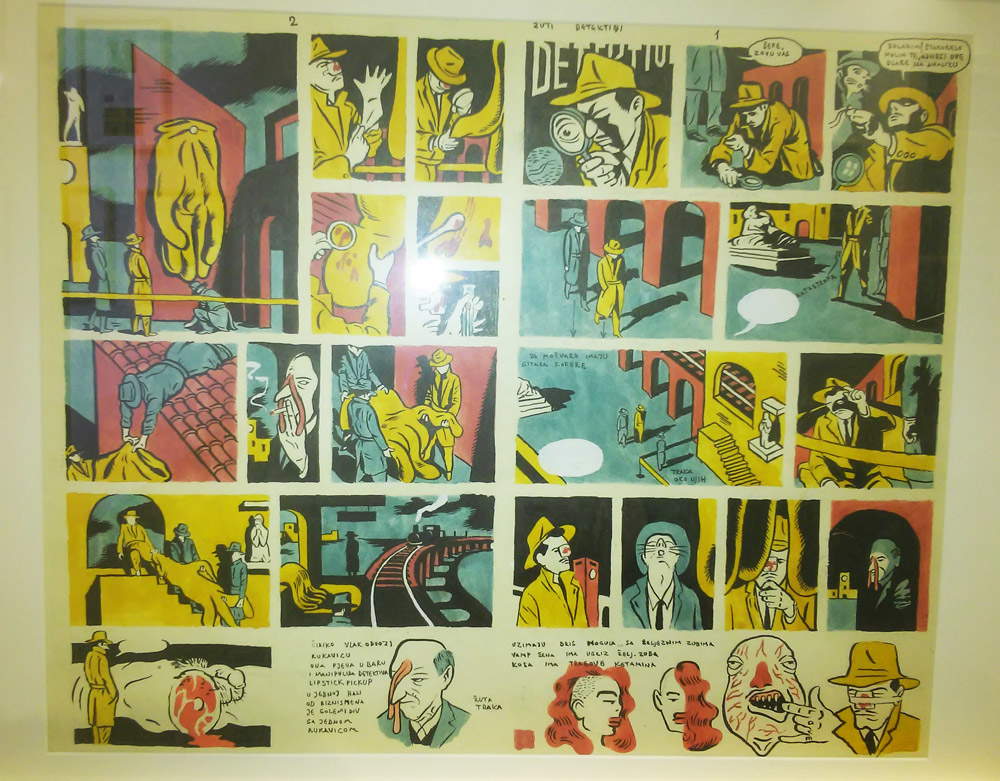

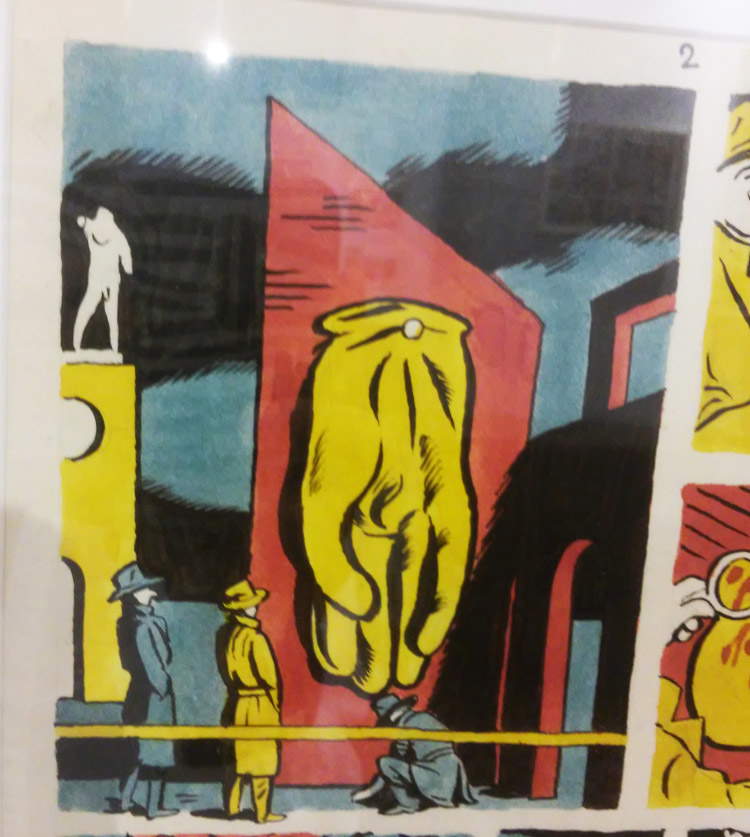

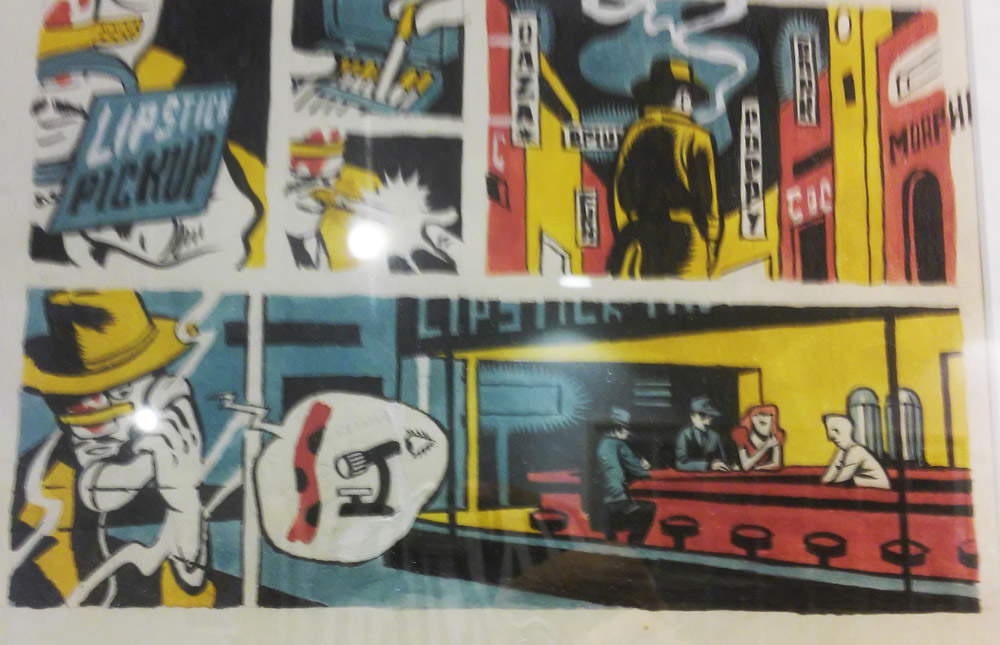

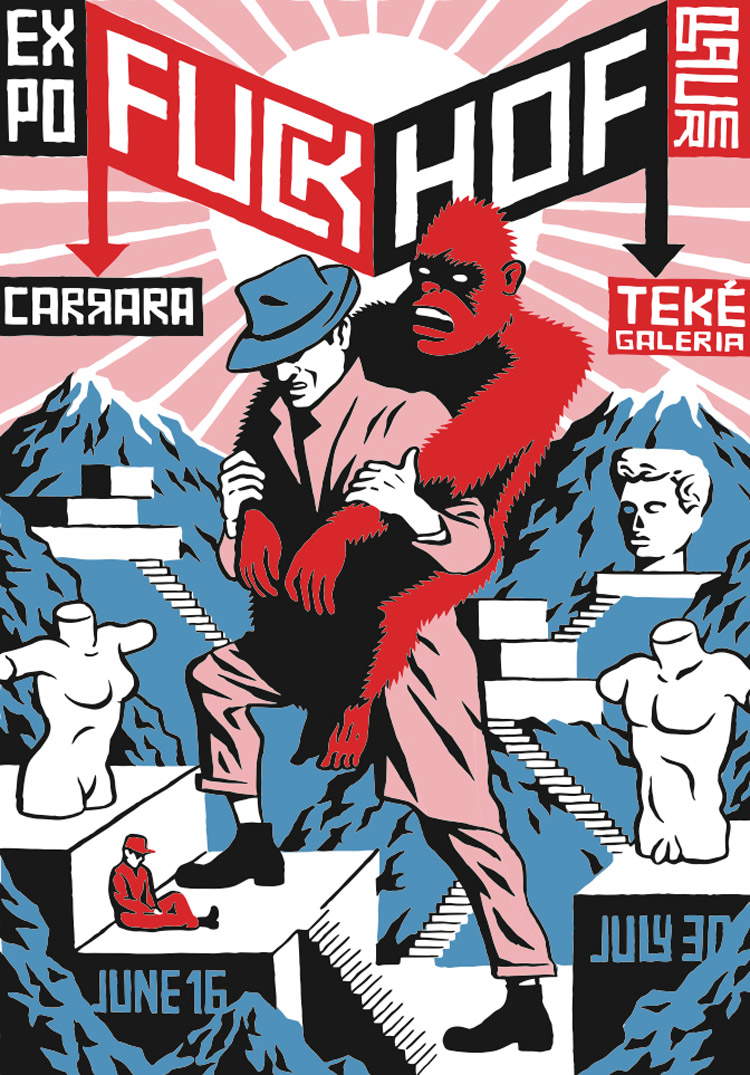

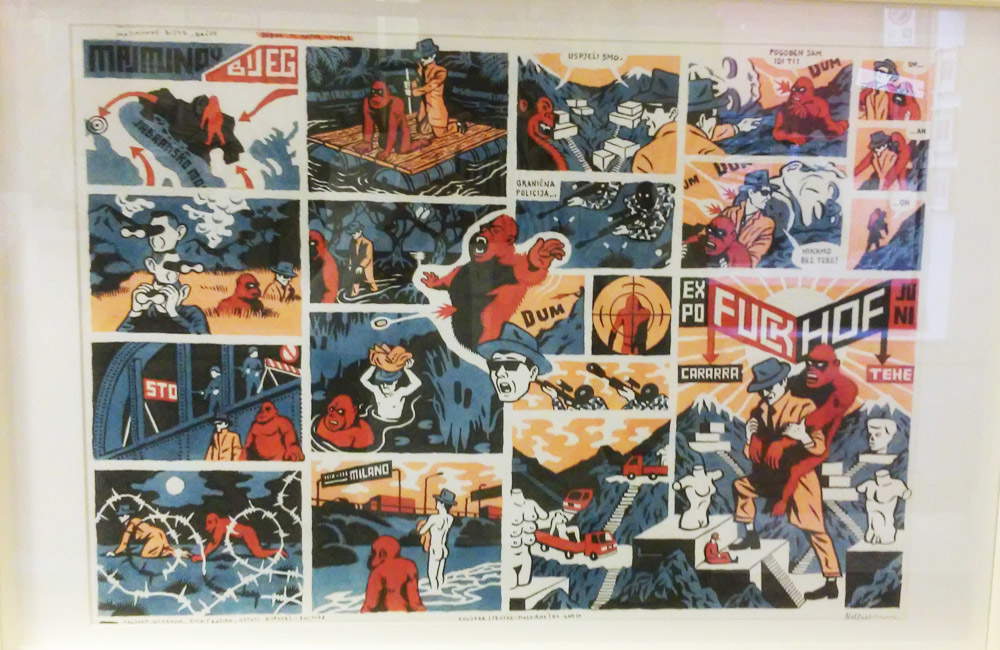

By contrast, of a totally opposite sign appears Inspektor Gürtel, a work from 2015, thus slightly preceding Mister Morgen, published in 2016. Totally opposite because if Mister Morgen is a highly personal work and, in a certain way, also autobiographical and the result of the artist’s direct experience, Inspektor Gürtel takes the form, on the contrary, of a “total entertainment” (to use the same expression Hofbauer used to describe his graphic novel), filled with references to historical comics, cinema and twentieth-century art. It is a kind of Balkan Dick Tracy (but with intensely more noir tones) that immediately helps to familiarize with the artist’s imagery. The protagonist is an inspector struggling with a bloody affair, occurring amidst metaphysical settings reminiscent of Giorgio De Chirico ’s Ferrara (complete with a direct quotation from the Canto d’amore), which the detective in a fedora and yellow raincoat investigates, wandering through the sordid slums of a city populated by unlikely vamps who seem to have come straight out of the paintings of Emil Nolde and grim figures who find themselves at the counter of a bar that expressly cites Hopper’s Nighthawks. But there are also detective and science fiction b-movies, there are the film noirs of American cinema (Hofbauer specifically mentions The third man and Chinatown), there are the comic books of Charles Burns. A character similar to Hofbauer’s inspector returns, moreover, in the poster designed especially for the Carrara exhibition, where a detective is seen carrying a gorilla on his shoulder (the primate is one of the most frequent topoi of his production) as he sets off toward the Apuan marble quarries: the poster is preceded by an ironic panel, Majmunov bijeg (“The Monkey’s Escape”), where we witness the aforementioned detective’s attempt (with success) to bring the red ape to Carrara, amidst a thousand misadventures.

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Mister Morgen (2016) |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Inspektor Gürtel (2015) |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Inspektor Gürtel, detail |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Inspektor Gürtel, detail |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Fuck Hof (2017) |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Majmunov Bijeg (2017) |

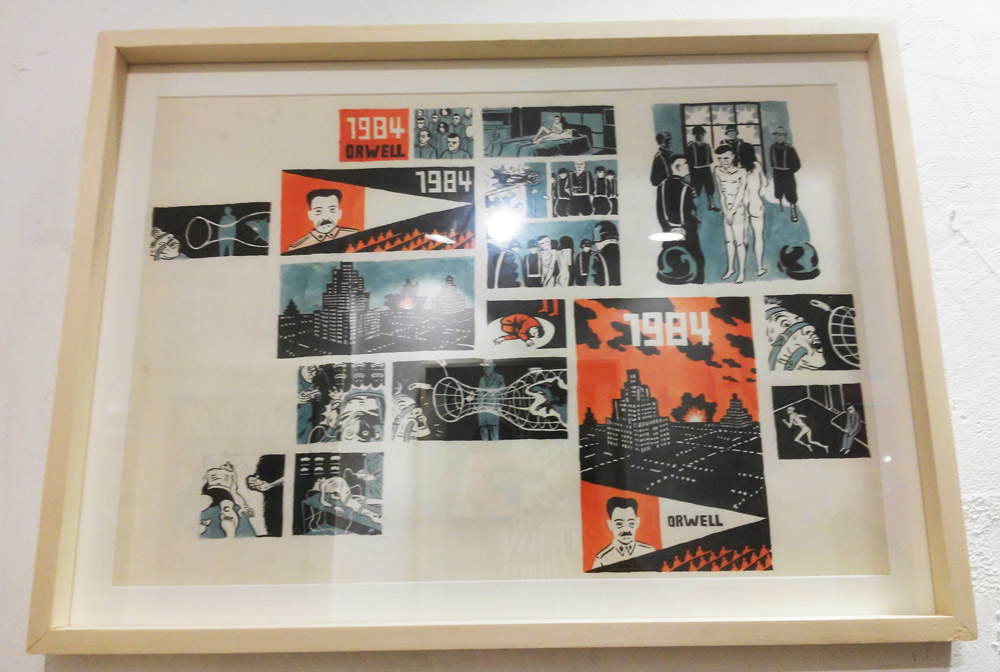

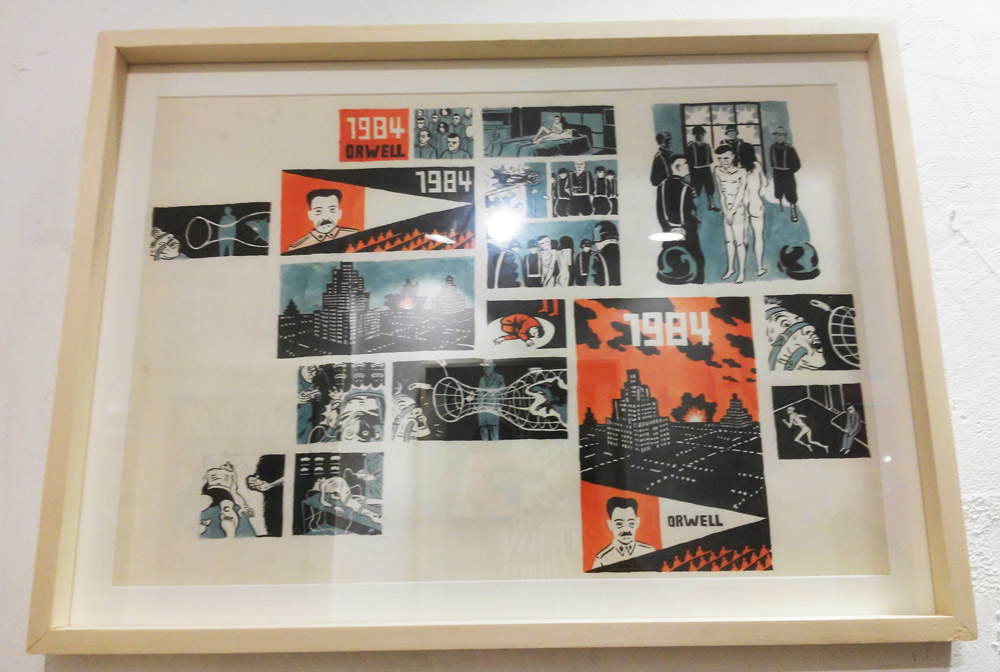

It is somewhat difficult to establish a canon within Hofbauer’s production, although it is instead possible to trace the origins of his alienated imagery, which finds, meanwhile, fertile ground in the dystopias of every era: one of the main references is George Orwell’s 1984, a book featured in the exhibition in an edition with a cover designed by Hofbauer (but there are also illustrations that the artist draws openly referencing the Michael Redford film). Cinema, after all, constitutes a constant source of inspiration: directors such as Lynch, Scott, and Jodorowsky concur to form those distorted scenes where Hofbauer sets his creations. “The metropolitan portraits of the Croatian capital,” writes curator Alessandra Ioalè, “are, in fact, the real subject of his stories. Unpredictable and transdimensional stories populated by social misfits, outcasts, deformed creatures and post-decadent life forms. Unusual subnormal humanoids whose presence makes the atmosphere of the tale surreal, to whose narrative development the author adds just enough nonsense to create mystery, doubt and arouse uncertainty, sometimes even bewilderment and shock, in the reader.”

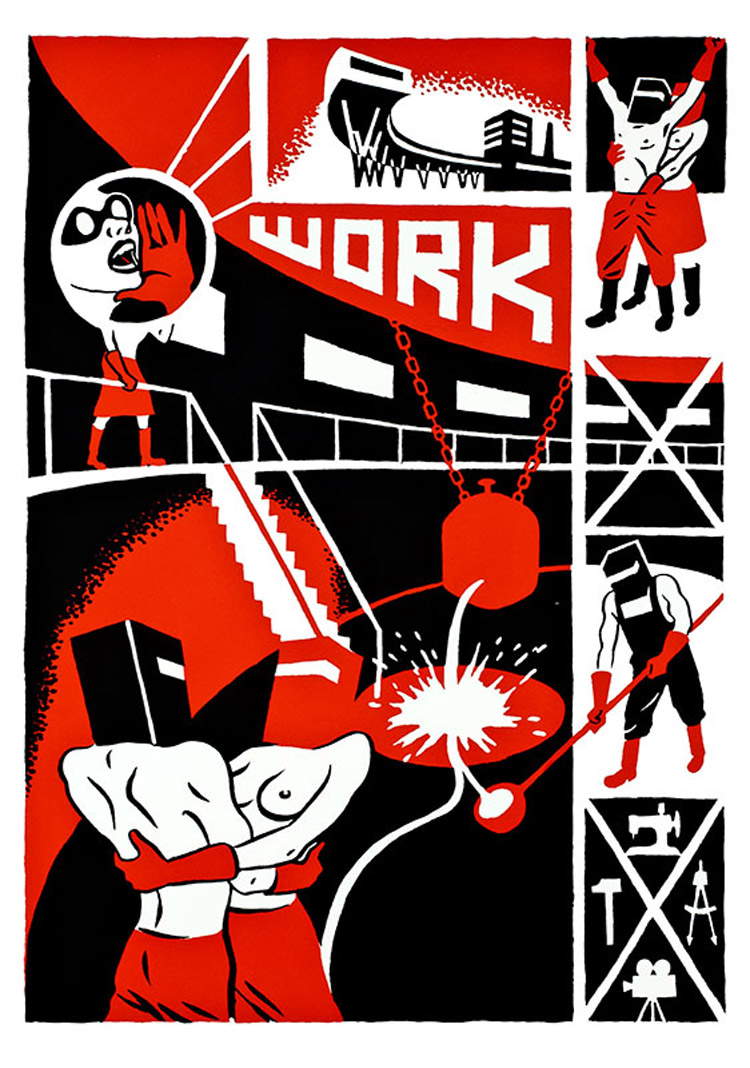

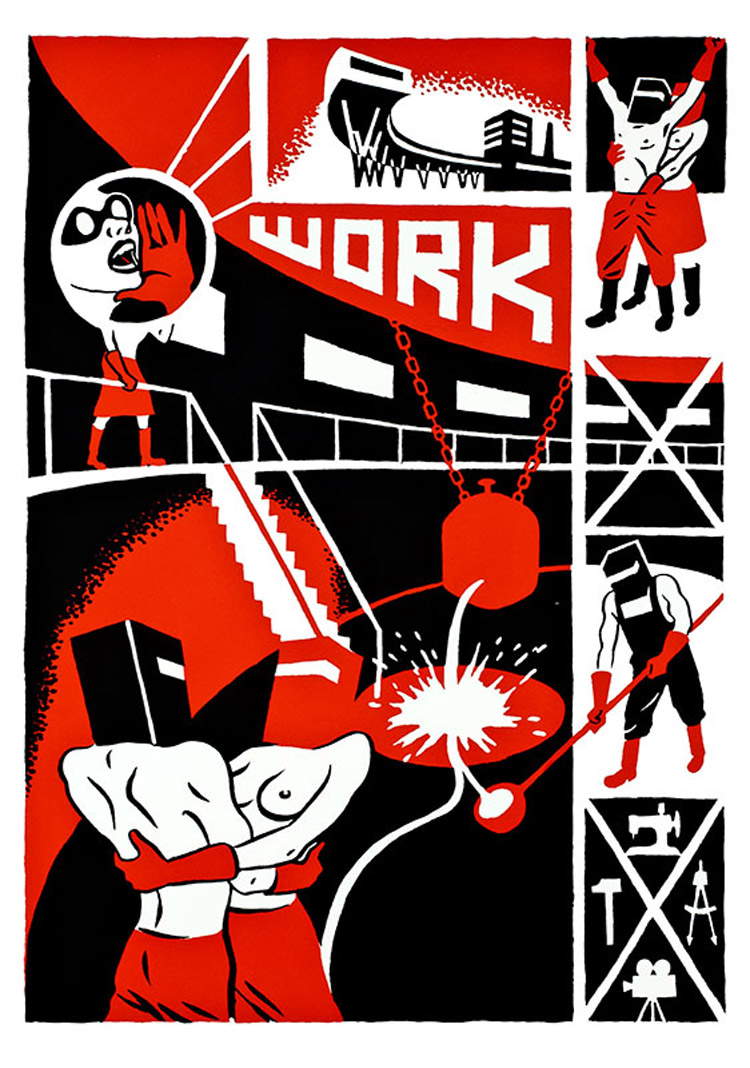

Another constant in Hofbauer’s work is the recovery of Soviet propaganda art, with which an artist from the Balkan area cannot fail to reckon. A retrieval that has a double significance: building a repertoire from which to constantly draw images and symbols, while at the same time overturning their meaning. Particularly illustrative is a playbill where, inside a gloomy foundry, a direct quotation from Aleksandr RodÄenko accompanies the word “Work,” “to work,” which is disregarded, however, by a pair of workers who ditch their fireproof overalls and strip down to join in an intercourse with the woman who already has her hands inside the man’s pants. Igor Hofbauer’s aesthetics find their foundation in Russian constructivism, emptied, however, of its political meanings and applied, with its geometric constructs, with its attention to the written word, with its tendency toward synthesis, with its flat, well-defined forms, to today’s metropolitan society and all its anxieties. And of constructivism Hofbauer also makes his own theaesthetic importance as a very part of the message: a mode of expression that is also rooted in Croatian illustration of the previous generation (Hofbauer has often pointed to Boris Bućan as one of the artists who most influenced him) and that relies heavily on style to bring out content. The importance of the past, for Hofbauer, lies in its recognizability: it is the artist’s duty to actualize it in the forms he deems most appropriate to his own time.

|

| Igor Hofbauer, For Work |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Illustrations for 1984 by George Orwell |

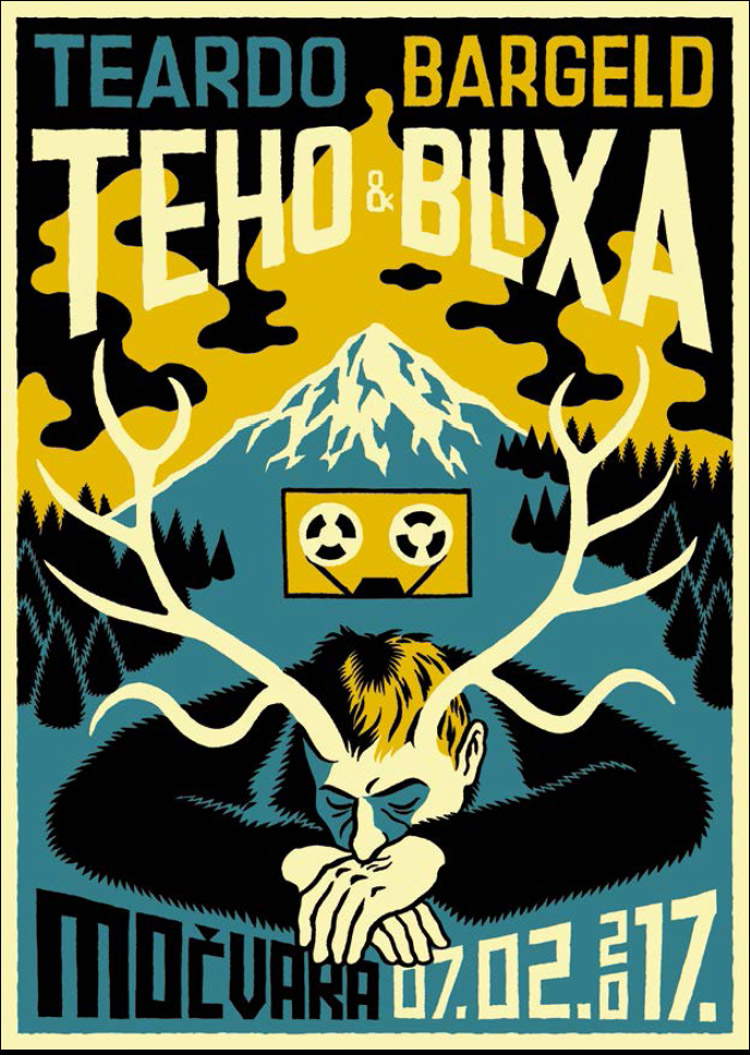

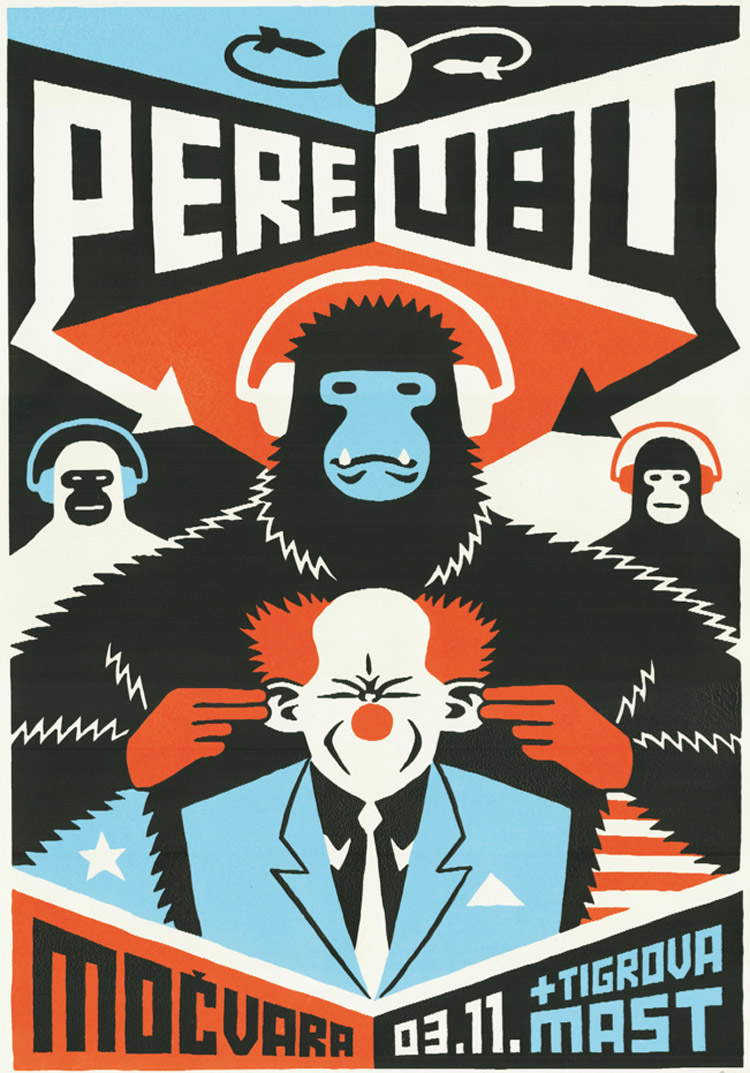

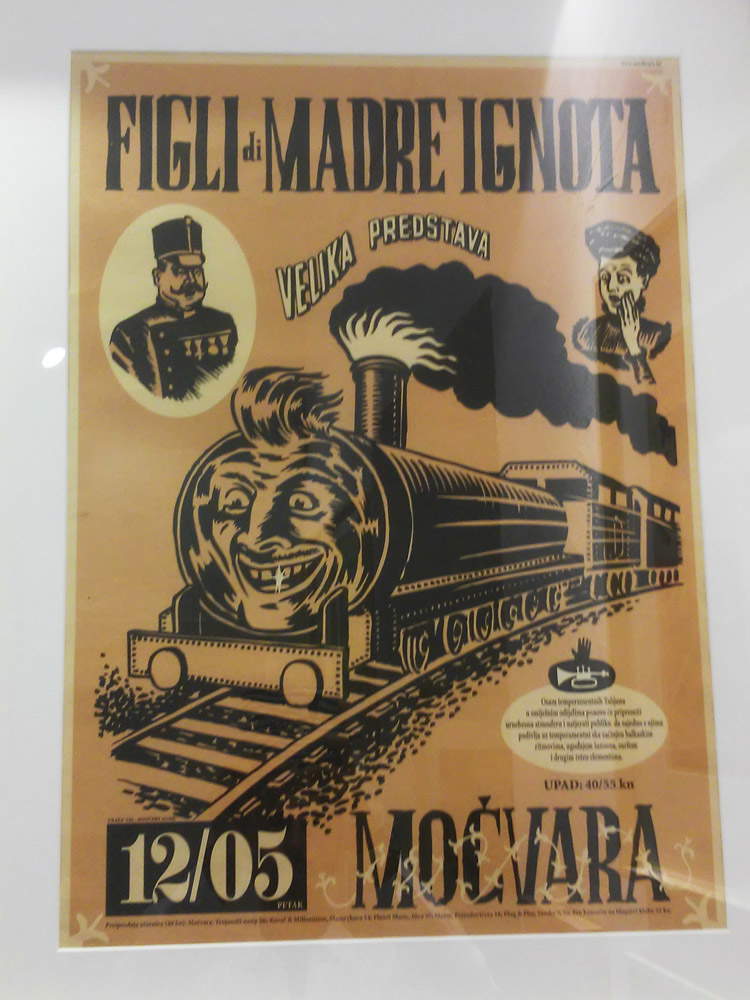

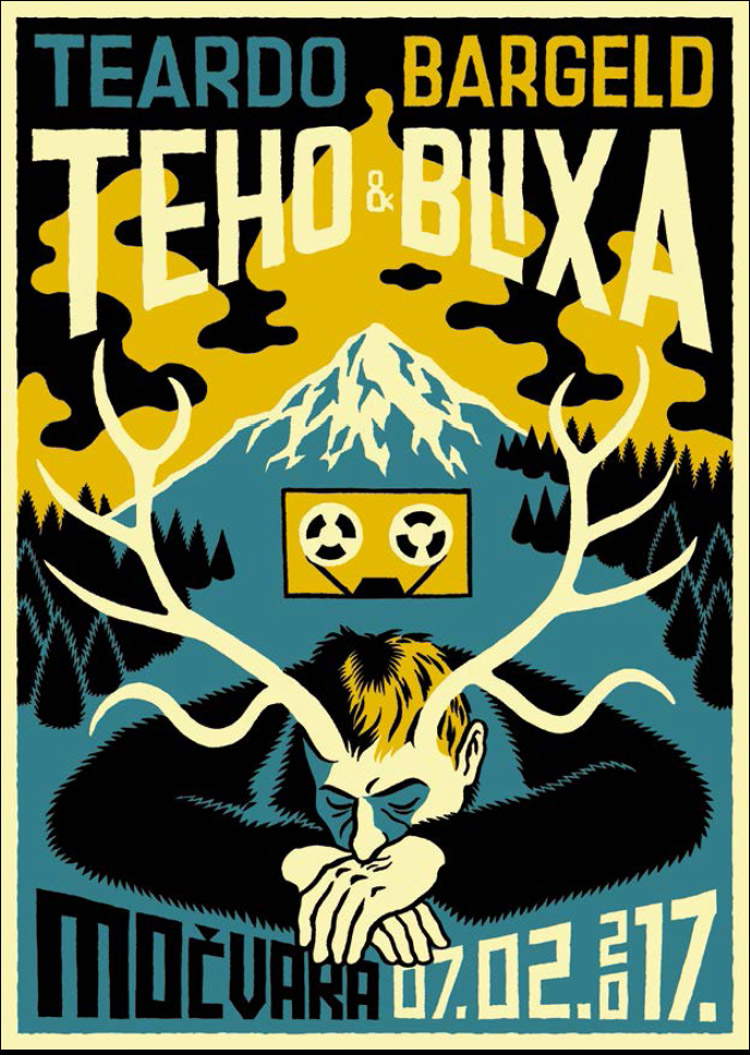

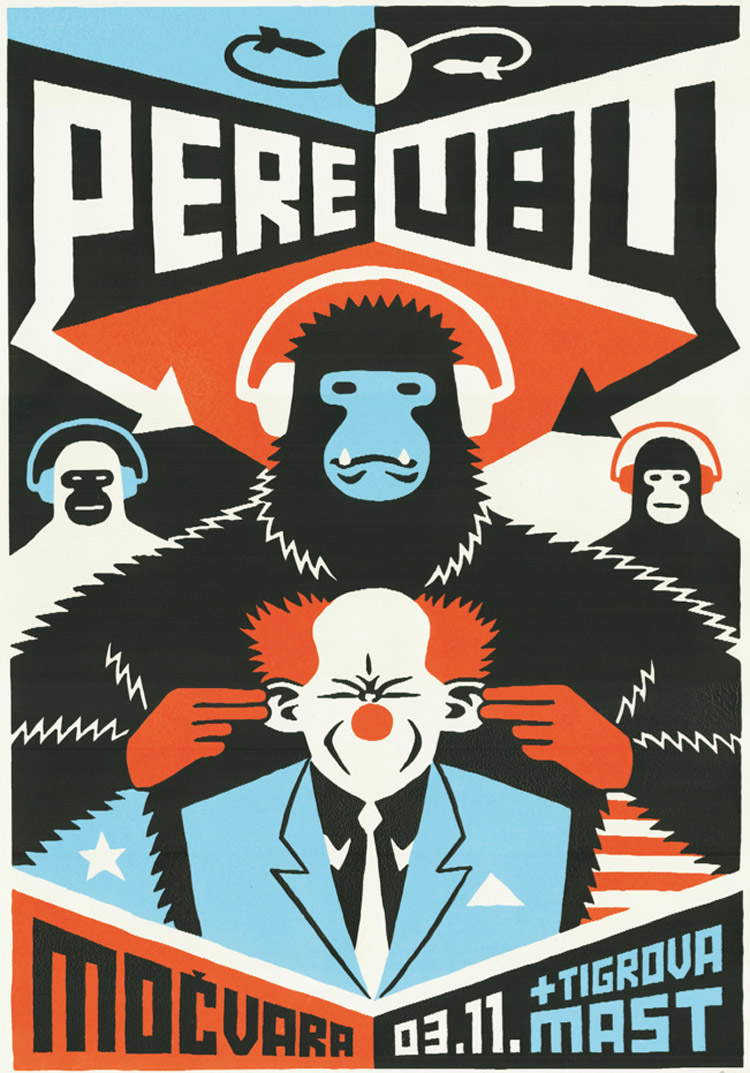

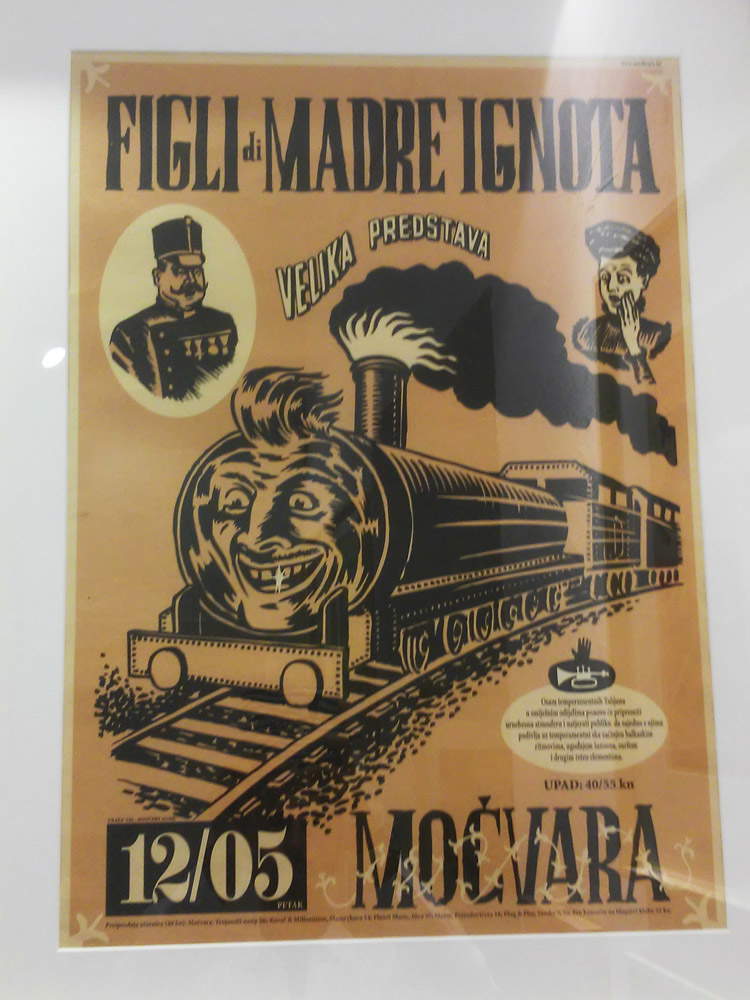

These characteristics, characteristic of Hofbauer’s language since his beginnings, are also found in his extensive production of concert posters and artwork for musical groups. Particularly intense in this respect is his activity for the club MoÄvara (i.e. “Swamp”) in Zagreb, with which there has always been a mutual exchange: since 1999 Igor Hofbauer has linked his name to that of the Croatian underground concert venue, and also thanks to the flyers produced in this context he began to circulate his name insistently, and MoÄvara has built its identity also (and perhaps even above all) with the contribution of the artist’s drawings. Without any particular strategies other than to focus on a talented artist. Posters entered the imagination of those gravitating around the Croatian underground environment (and beyond), and then gathered in various collections. Hofbauer told Vittore Baroni about the circumstances that led him to MoÄvara: “In Croatia, the dark and difficult 1990s of Franjo TuÄ‘man, his absolutist nationalistic regime, and the apathy existing in the country caused a concentration of youth frustration and, as a result, the creation of a countercultural platform. This initiated in Zagreb the creation of all sorts of youth organizations. One of these was MoÄvara. They knew me and asked me to make posters for their events. [...] I got carried away by that energy and it was important for me to work on the posters because I really cared that more people would be able to come and hear the band. I also helped the bands unload their equipment, offered them a place to sleep and eat. That’s how, in short, my posters ended up on the walls of the streets.”

There are some very striking pieces on display. There is the first silkscreen edition of the poster Hofbauer made in February this year for the Teho Tehardo and Blixa Bargeld concert. There is the Heavy Trash concert poster, in which the rockabilly aesthetic, which often surfaces in the Croatian artist’s production, was able to rise to the role of the absolute protagonist of the composition. Again, there is the poster for an important concert held at MoÄvara on November 3, 2013, that of Pere Ubu, one of the most important bands in the entire history of rock. There is the poster for a concert by the Italians Figli di Madre Ignota that features a sort of adult, distorted and disturbing version of the Thomas train, the 1980s British cartoon voiced by Ringo Starr, George Carlin and Alec Baldwin, among others. They seem almost like pages from a single tale spanning two decades, capable of alternating high and low language, able to draw from the great history of art but also from the folklore of the Balkans, and above all skillful in its attempt to give an alternative and new identity to a city eager to leave behind a heavy and oppressive past.

|

| Some posters by Igor Hofbauer |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Poster for Teho Teardo and Blixa Bargeld concert at MoÄvara in Zagreb (2017) |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Poster for the Heavy Trash concert at MoÄvara in Zagreb (2016) |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Poster for the Pere Ubu concert at MoÄvara in Zagreb (2013) |

|

| Igor Hofbauer, Poster for the Children of Mother Unknown concert at MoÄvara Zagreb (2006) |

Igor Hofbauer is an artist with a penchant for drama. The baseness, the human misery, the despair, the alienation of his characters who wander among the gray ruined buildings of a ghostly and desolate former Yugoslavia seem to leave no hope, they seem to communicate that there is no possibility of rising up, or at least of attempting the feat: after an initial moment of natural and almost predictable disorientation, one feels a sort of empathy, probably also in line with the author’s idea, and yet one seems to be dealing with characters who are already largely doomed. Is it possible that no glimmer of positivity lurks behind Hofbauer’s works? This is perhaps the most natural question that arises from viewing his comics, his posters, his illustrations: it is therefore possible and legitimate to make a couple of considerations.

The first: often Igor Hofbauer’s hallucinated fantasies are dystopian visions rather than timely narratives, and thus have more the character of warning than that of description. With all that this means and entails, however much the artist, in a recent interview, declared that he does not want to attribute any particular social value to his comics. The second: if it is necessary to discern even the slightest openness to change, it can be encountered especially in posters and playbills. Therein lurks both the obstinacy of an artist who, practically from nothing, has managed to create a significant part of the cultural identity of a city, and a certain will, more or less conscious, to oppose an attempt at reaction that inevitably flows through art and music and that can provide the observer with more than one food for thought. It is then necessary to point out that Igor Hofbauer’s art seems to be characterized by an openness, even to the past, which is substantiated, again quoting curator Alessandra Ioalè’s essay, in looking at tradition and “grasping its ingredients” so that “it can be reworked and developed to make it still relevant in the transmission of new messages to a community in constant change.” Hofbauer’s art becomes the bearer of “moods and customs, anxieties and desires, anomalies and excesses” of a specific community (his: but it could also be ours): it is up to the viewer to fill the spaces that Hofbauer creates between the folds of his production.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.