If the Venice Biennale becomes a photo safari among outsiders. The limits of Pedrosa's exhibition.

Exactly fifty years have passed since an “Initiative Committee for Naïve Painting at the Venice Biennale” wrote to Carlo Ripa di Meana, who had just been appointed president of the recently reformed Biennale, an impassioned letter asking the institution for full recognition of the naïf movement, to be sanctioned perhaps by the presence in the exhibition of a’a salon dedicated to those ’naïfs’ who had for years been ostracized by most critics, excluded from emblazoned circles, often even mocked, but who were nevertheless able to rage on the market, embodying with solar vividness the assumption that art history and the history of taste often circulate on distant roads. It was the spring of 1974: “We are sure,” the committee wrote addressing Ripa di Meana and the board, “that none of you will have missed the importance of the historical phenomenon of the ’new imagination’ : the growth of a movement, defined as art naïf, which is quantitatively and qualitatively a new fact in the development of the sensibility of ever broader masses, the so-called emerging energies of our time. We are no longer dealing with flashes of extra-academic or primitive or popular imagination [...]. We are dealing with a movement that will no longer stop and will grow, even under the present difficult conditions of peoples’ culture and the complicated relationship with the arts and the aesthetic awareness of the masses. It is in grace of this precise and firm consciousness that we ask you to concretely recognize to the new naïve painting that full cultural status, that professional dignity, that artistic respect that is due to it, against any elitist or subordinate conception of culture.” The signatories of that letter could not have imagined that precisely during a round anniversary, in 2024, legions of folk and brut artists from all over the planet would finally be exhibited at the world’s most important exhibition and that coveted institutional admission of “marginalized” art would have finally arrived, although the curator of the 60th edition of the Biennale, Adriano Pedrosa, struggles to imagine it as an acknowledgement, and prefers to think, if only somewhat implicitly, that the hypertrophic convening of indigenous, queer, outsider artists at his Biennale is, if anything, the peaceful consequence of a kind of natural course of art history.

In a sense, Pedrosa is right when, during his interview with Julieta González published in the catalog, he states that it is rather easy for a European or U.S. visitor to recognize contemporary artists from what he calls the “Global South,” since “since the late 1990s and early 2000s, contemporary artists from our part of the world have gained greater visibility: If not all of them, at least some of them are traveling and exhibiting in museums, galleries and biennials.” In Italy we perhaps feel it less since our contemporary art museums most of the time follow other orientations, but it is enough to visit the main fairs to become aware of the tons of African, Asian, Latin American art proposed by so many gallery owners who, inevitably, intercept a taste and an interest that for at least a twenty years, and with increasing constancy, have been exciting the appetites of collectors from halfway around the world, and in this sense the Italians are no exception. Foreigners everywhere - Foreigners everywhere, the international exhibition of the 2024 Biennial, therefore does not unveil any substantial novelty worthy of note (even the essays that make up the catalog, minus the only unpublished contribution by Claire Fontaine, constitute a collectivization of articles published between 1998 and 2023): it should, if anything, be read, on the one hand, as a moment of official consecration for artists who have been on the market for years, even with decidedly high quotations, and on the other hand, as a means of amplifying discussions that have been underway for some time, as a means that delivers to Biennale visitors artists that other institutions, in previous years, have brought to the attention of European and U.S. audiences. At the Arsenale, the itinerary opens with Claire Fontaine and Yinka Shonibare, artists well known to frequenters ofcontemporary art, represented by two leading galleries (respectively the Parisian Mennour and the New York-based Goodman), but the discourse could be extended to a decidedly consistent part, perhaps even the majority, of the living artists in the exhibition, well present on a market dominated by white, Eurocentric cash, whether they are self-taught or popular artists, or, on the contrary, artists with a traditional, formal, academic background: Frieda Toranzo Jaeger (represented by the Barbara Weiss Gallery), Emmi Whitehorse (Garth Greenan), Greta Schödl (Labs Gallery), Julia Isídrez (Gomide&Co), Dana Awartani (Lisson), and so on arrive in succession. Even the aboriginal Naminapu Maymuru-White, “grand old yolnu” as the captions in the exhibition present her to us, has entrusted the care of her interests to one of the leading galleries in the entire Asia-Pacific (Australia’s Sullivan+Strumpf, which is among the regulars at Art Basel).

The same assumption applies, of course, to the section set up at the Central Pavilion of the Gardens, where one finds, among others, Louis Fratino, that is, one of the artists currently most pumped up by the market (included in a curious and bizarre dialogue with Filippo de Pisis, on the basis of common homosexuality, at least to read from the captions), or the native Kay Walkingstick who had only one show with her gallery at thelast edition of Art Basel Miami, or even the native Aycoobo who won an award at the 2022 Toronto Biennial, while most of the nonliving artists (who make up a third of the names in this Biennial) have nonetheless already been shown in major exhibitions, from MoMA in New York to the Tate in London via many of the major international contemporary art museums. And if we imagine a Pedrosa wandering through the Amazon rainforest in search of the works of Yanomami shamans to reveal to European audiences images never before seen in our latitudes, we would be disappointed: the works of André Taniki and Joseca Mokahesi have been touring museums on our continent for at least twenty years, with the Fondation Cartier leading the way in 2003 with the exhibition Yanomami. L’esprit de la forêt.

The first consequence is therefore a sort of return colonialism that already enveloped the atmosphere of the past edition of the international exhibition, Cecilia Alemani’s The Milk of Dreams , and which, however, becomes an inescapable theme in an edition, the current one, that intends to place the theme of decolonization at the center of attention. The only one who does not shy away from the topic is Ticio Escobar in his essay published in the catalog, where he points out that “popular” artists have “the right to use all the channels and institutions (with which the dominant culture interrupts and interferes) and to use them as refuges, trenches or even as runways for potential flights”, so that “from this point of view one cannot criticize the decision to resort to the market and fight for fairer prices and greater recognition of popular creativity.” A more than correct observation, but one that opens up a series of questions of no small importance: can an artist who is put under contract by one of the most powerful galleries in the world and who brings his or her work into the most institutional contexts of the contemporary art universe really be said to be “excluded”? To what extent then can the narrative on which this Biennial has been set hold up? To what degree can we consider unconscious the art of a shaman who has spent the last few years traveling between Paris, London, Shanghai? Doesn’t this run the risk of harnessing this popular creativity by achieving an effect quite contrary to what was intended? The shaman obviously has every right to resort to the European and North American marketplaces to obtain economic, cultural, social recognition (indeed, the dream of many outsiders is precisely official recognition), and yet at the same time the public also has every right to question the effects of the operation, to ask itself some questions about the spontaneity of an artist who has been measuring himself against the Western market for years, about his real degree of exclusion, about the real reason for his presence: is he here because we are really interested in what he has to say and maybe even in the conditions of his community, or is he here because they exhibit him to us as a curiosity that we will later forget about when we are tired of admiring the craftsmanship of his hands that never touched modern Western tools? Already at the time of the naïf explosion Giancarlo Marmori, in one of his memorable articles, observed that “a naïf, once discovered, cannot ignore for long that he is one,” and that “today a naïf has little chance of a clandestine, authentic and serene life.” it was true in the mid-1970s, when Marmori was writing his piece in L’Espresso, it is even more true today, in the post-globalization world, in the age of the Internet and social media, and with theart world audience accustomed to traveling, one week to Venice, the next to New York, the next still to Seoul.

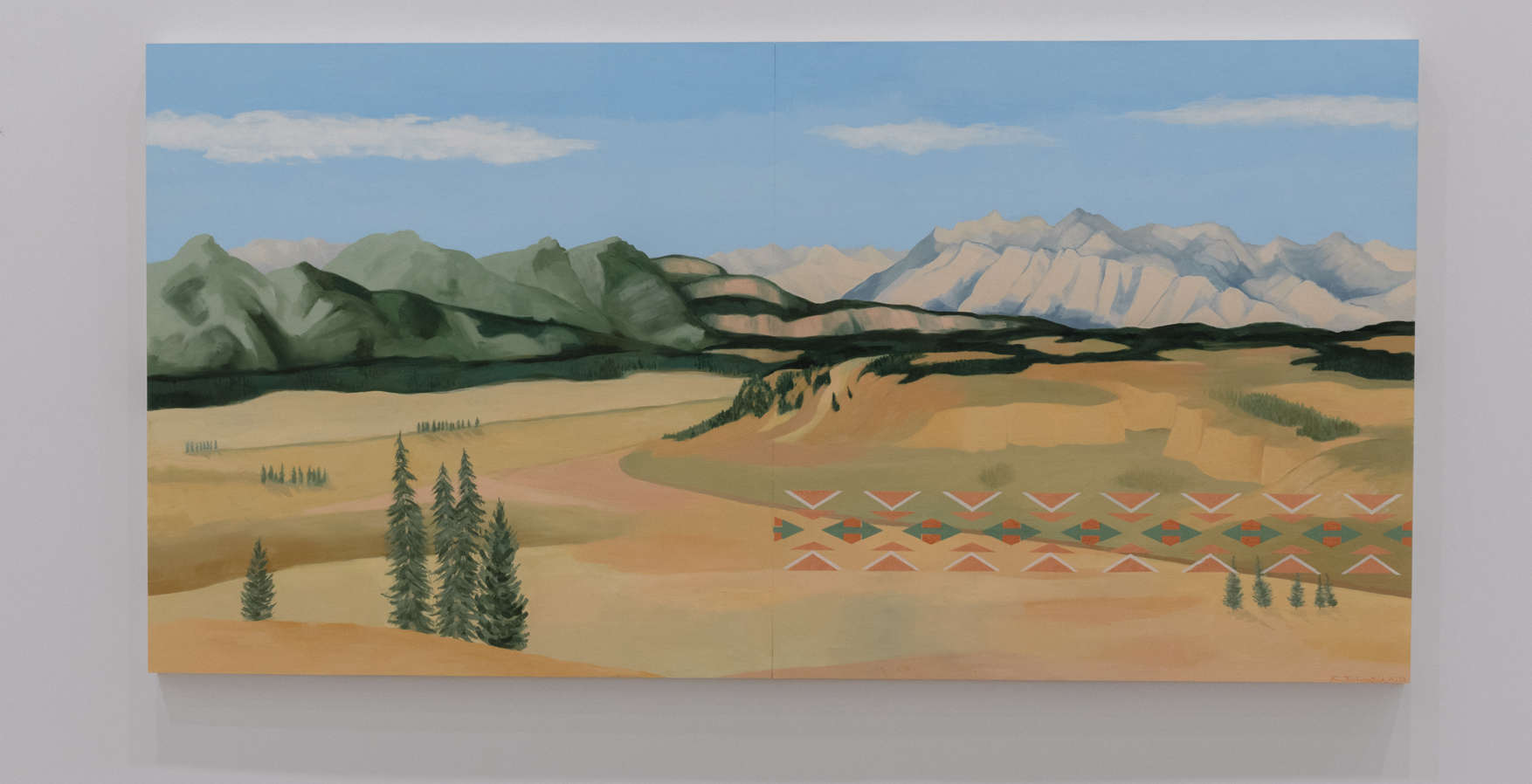

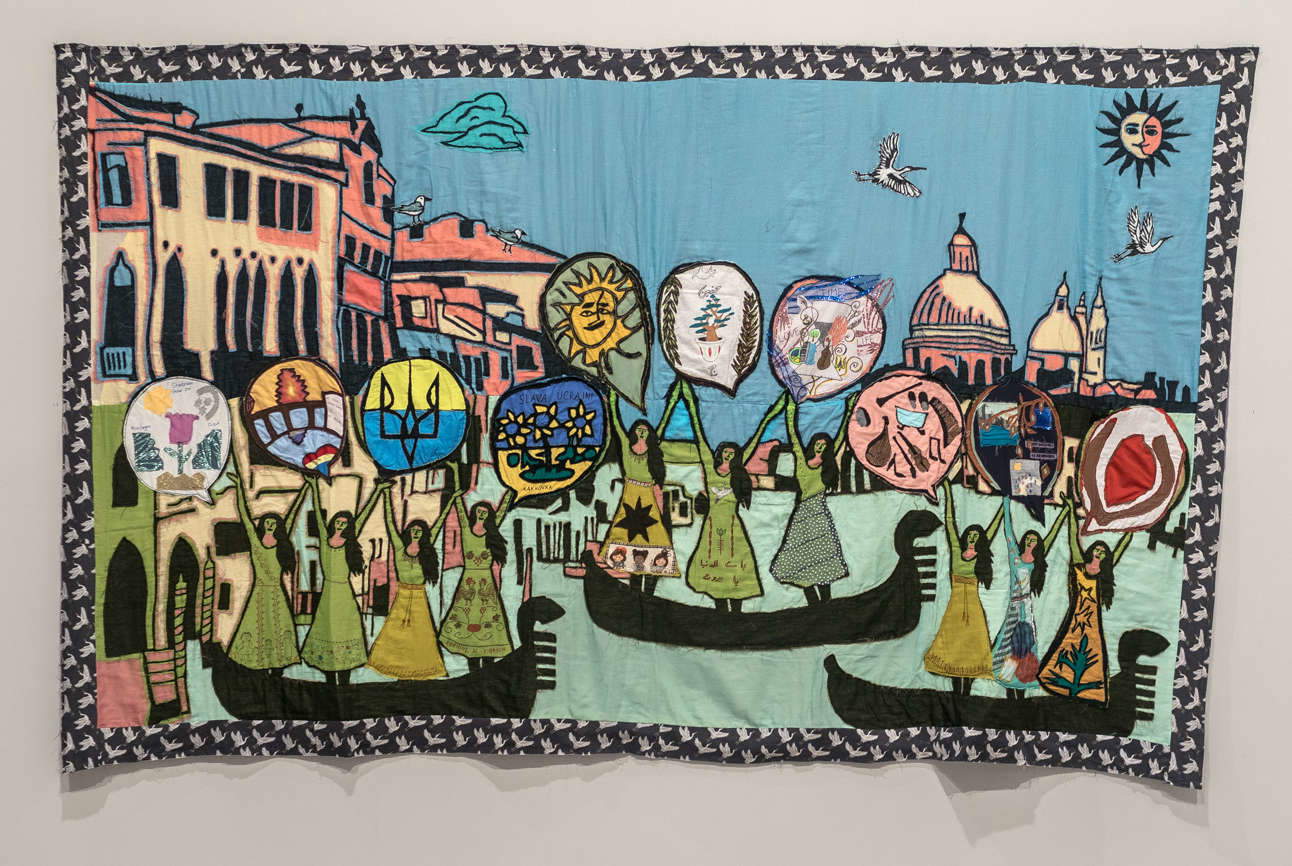

Certainly, several of the artists or projects chosen by Pedrosa for his exhibition (which, unlike the past edition of the international show, is distinguished by greater clarity, cleaner arrangements, and more immediate freshness) are capable of surprising the audience, especially if one did not know them: one is then genuinely impressed when faced with the visionary power of Santiago Yahuarcani, a self-taught painter from the Uitoto nation, who, with his works set among the intricate forests, guardian spirits and animals of his Amazon, brings to mind the universal judgments of our churches of the Two and Fourteenth centuries. We become engrossed in the stories of Nigerian mototaxi drivers told in a candid video by Karimah Ashadu. Touching are the textiles of Turkish artist Günes Terkol, whose fabrics transfigure current events into a story that seems almost devoid of any real temporal dimension, giving life to polyphonies of female voices with which we immediately connect. The tidy photographs by Angolan Kiluanji Kia Henda manage to communicate effectively and poetically what privilege is, what the social divide is. One is captivated for a few moments by the sparkle of the golden ceramic sculptures of Victor Fotso Nyie, a young Cameroonian who has long lived and worked in Faenza. One can be pleased with the recognition that this edition of the Biennale accorded to Nedda Guidi, a relevant ceramist long marginalized, and yet included in the exhibition not so much for her pioneering role in the path of ennobling ceramics that traversed the art of the second half of the twentieth century, but rather because she was a " queer woman, a convinced feminist." Still, one gets to essay the acuity of projects such as Marco Scotini’s Disobedience Archive or Pablo Delano’s Museum of the Old Colony . With these and a few other acuities removed, the same comment that Jonathan Jones, the Guardian’s well-known critic, wrote eight years ago for the exhibition of Indian artist Bhupen Khakhar (featured in this edition of the Biennial) held at the Tate in London applies to Pedrosa’s Biennial: “why is Tate Modern exhibiting an outdated, second-rate artist whose art is reminiscent of the kind of British painters it would never let through its doors?”

One could ask Adriano Pedrosa the same question, given the large amount of outsider, folk and naïf art in his Biennial: what difference separates a self-taught artist born and raised in the Amazon rainforest from, say, one of the many peasant painters of postwar Emilia who had never entered a museum or picked up an art history book? What is different about a Diné native and an Apennine shepherd who, quoting Soffici, has never seen a professor’s mustache? What characteristics do our Ghizzardi, our Zinelli, our Bolognesi have that do not fit that definition of the outsider as "an artist who is on the margins of the art world just like the self-taught, folk artist or popular artist" rendered by Pedrosa in the catalog of his exhibition? What a bummer for the Committee fifty years ago: marginalized in the Biennale yes, but only if exotic. The only justification for the exclusion of European or North American outsiders (the only one in the exhibition, it is not clear why, is the Austrian Leopold Strobl), beyond of the fact that an Italian, a Frenchman or a Spaniard would end up watering down our mea culpa for the centuries of colonialism to which we have subjected the rest of the world, is probably the specific weight that irregular art, folk art, and folk art have in the economy of art from other continents.

Starting from this assumption, it then touches on the question of whether this is the most serious and the most correct way to include the Venice Biennale as well in the ongoing processes of cultural decolonization. That is to say: is bringing a monolithic agglomeration of excluded, indigenous and queer people to Venice, dogmatically cutting off everything else with very few exceptions, really useful? Probably not, for several reasons. Meanwhile, even with all the excellent intentions that certainly animate the artistic direction of this Biennial, it ends up fueling, albeit unwittingly, a dynamic of confrontation that is not even in the interests of the excluded that the exhibition intends to bring toward the center (recalling Errico Malatesta: “the oppressed masses [...] will not be able to emancipate themselves except through union, solidarity with all the oppressed, with all the exploited of the whole world”). A dynamic that, experienced in other fields and at other levels (for, as we know, the visual arts now count for little or nothing anymore) necessarily entails, and we can see this from the reality of the facts, the strengthening of the populist, nationalist, reactionary afflatuses that never cease to shake the “North of the world,” to use the terminology dear to the curator of this Biennial. After all, it is difficult not to glimpse a logic of opposition when one understands art history not as a historical process that has always had and will always have regional and local ramifications, but rather as a kind of settling of accounts with the past, as a revenge, as an attack on a rule. Besides, it is not useful because it falls into the risk of transforming the Biennale not into the cross-section of the contemporary world that it should be, perhaps with some claim to identifying a future direction, but into a kind of movie world divided by rooms, into a compendium of folklore and craft productions from what we would once have called the “third world,” in the corresponding exhibition format of a photo safari. This was implicitly confirmed by the dense gauche caviar farrago at home, who already during the preview days were indulging in the colorful exhibition capable of offering us a compendium of the thousands of wonderful craft techniques of the global South. Is there not a risk of digging a further furrow between the West and the rest of the world? Doesn’t setting up a showcase in Venice in which to display a sequence of batiks, Andean textiles and shaman drawings separate from everything else expose these artists to the danger of feeding stereotypes about them? Or of making even more evident that marginality that one would like to undo? Isn’t the attitude that informs Foreigners Everywhere - Foreigners Everywhere in danger of being so much like that of the ethnologists who set up their cabinets of curiosity centuries ago? And then, incidentally, can’t we finally get rid of the idea that a fluid artist should still be perceived as “strange”?

The limitations of the Pedrosa Biennial also emerge from the three “Historical Cores,” three small reviews of twentieth-century art history, one more embarrassing than the other, designed with all the flaws of the Contemporary Core. The first Historical Core one encounters (if one wants to start the tour from the Arsenale), Italians Everywhere, we quote from the catalog, “brings together works by Italian artists who have traveled and lived abroad, developing their careers in Africa, Asia and Latin America, as well as in the United States and Europe,” “first- and second-generation Italian immigrants who have in turn become foreigners in the Global South and beyond during the 20th century.” One does not quite understand the criteria for the selection, because beyond artists who actually left Italy to move permanently elsewhere there are also those who, like Galileo Chini, in Thailand have stayed just long enough to complete a work he had been commissioned to do there (curious, moreover, to note that Chini’s only in situ work, the frescoes that adorn the dome of the Central Pavilion of the Giardini, was left in the dark: not even the minimum wage toward one of the selected artists). But beyond the reasons for the selection, the Nucleus is nothing more than a sort of sticker album that occupies an entire room, a shapeless swarm of artists unconnected to each other, an indistinct jumble that brings together often profoundly different experiences, and not even the beautiful(the cavalete de cristal, the transparent displays designed for Lina Bo Bardi in 1968 for the MASP in São Paulo, the museum now directed by Pedrosa) does not succeed in improving the results of a very bad exhibition.

It doesn’t get any better with the Gardens’ two Historical Cores, the one dedicated to abstraction and the one on portraiture, both animated by the purpose of observing the declinations of early 20th century movements rendered by artists who worked far from the continents in which the avant-gardes emerged. Here again, there is no historical framing other than to show that, in the wake of what was being produced at the beginning of the century in the driving centers of Europe and North America, in the rest of the world there were those who made their own contributions and developed locally the suggestions coming from other centers. This is what has always happened in the history of art: the Renaissance was born in Florence, but there has been a Lombard Renaissance, an Urbino Renaissance, a Ligurian Renaissance and so on, each with its own temperament and its own characters of originality. And yet no serious art historian would think of setting up an exhibition in a single room where a Boltraffio, a Fra’ Carnevale, a Ludovico Brea and so on would be scattered without providing the visitor with some coordinates for orientation, beyond a few biographical notes on the artists on display. For this is the situation before which the visitor finds himself as he walks through the two Historic Nuclei of the Gardens: an incomprehensible roundup of African, Latin American and Asian artists of the early twentieth century, juxtaposed without criterion, without guides (only brief biographies are present), without clear subdivisions, in a confusing mass where any distinction between even radically different contexts is lacking, where truly original artists, such as Tarsila do Amaral or Candido Portinari in the portraits section, drown among second- and third-rate painters, with the risk that the visitor ends up missing them. The Historical Cores are, therefore, also a missed opportunity.

It may sound like a paradox, but there was a fresher air at the Biennale curated by Ralph Rugoff, which we may not remember among the best editions in history, but it was the last one in which the management brought together artists from the “North” and from the “South” without ghettoization or showdown logic, putting on an equal footing as much the artistic products of the West as those of the rest of the globe, with the common goal of offering a worldview and trying to hypothesize a course. It is not certain that the hypothesis about the future is then correct, it is not certain that the times do not disprove the ideas of a curator, but at least in the past visitors were offered the opportunity to discuss a direction. Now, in order to find a visionary artistic proposal in Venice, one has to go outside the Biennale and see Pierre Huyghe’s powerful exhibition at the Punta della Dogana, because Stranieri ovunque - Foreigners Every where is a harmless, affable, axiomatic, unimpressive, at best summarizing exhibition.

The last two Biennales have been more concerned with the need to pander to a taste, have engaged in the search for antitheses, have added to discussions already started elsewhere, and without even adding particularly interesting contributions. Indeed, the 2024 Biennial has probably sanctioned a regression, since this year’s international exhibition imposes an idea of decolonization that seems to almost disregard any form of dialogue. After all, it is Pedrosa himself who, in the interview with Julieta González, states that the raison d’être of the two Historic Cores of the Gardens is to “challenge the Western canon.” And that of decolonization as a challenge to the West is, moreover, an idea that in the illusion of solving one problem ends up creating others: in the New York Times, Jason Farago has correctly pointed out the welds between this kind of narrative and the anti-colonial rhetoric of a Putin who seeks to promote his Russia as a friend of African countries, while at the same time attempting to impose his own imperialism on Ukraine outside of history. Then this is not really the cultural decolonization we need.

Is there, however, another possibility? Certainly, and it can be found in some of the national pavilions (although there are not many where it goes beyond a mere presentation of the excluded at home): in that of France, for example, where Julien Creuzet indicates, with a total work imbued with poetry, that the process of decolonization should be imagined as a moment of rethinking not only our political structures, but also our positioning in the world. Decolonization, then, as restructuring, rather than as challenge or reckoning. Otherwise we can continue to think that we have done ours by being content with seeing a few exotic naïfs. The Committee of fifty years ago would probably have rejoiced.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.