If the machine is an instrument of poetry. What the Jean Tinguely exhibition in Milan looks like.

Jean Tinguely returns to Milan seventy years after the first time and forty-four after he chose it to declare Nouveau Réalisme dead, on the tenth anniversary of its founding, that is, the time when all the artists of the movement gathered in Milan to take part in a three-day funeral, culminating on the night of November 28, 1970, in front of the Duomo, in front of eight thousand people gathered on the square. Tinguely had envisioned a spectacular performance, a very singular catafalque to celebrate the death of the movement: a “self-destructive anarchist monument,” a machine killing itself in front of everyone, on top of a stage, in one of the most beautiful and most famous squares in the world. He had called it The Victory, or The Suicide of the Machine, and staging it had required a month of preparations, or, as Tinguely himself would write, of “preparation, construction, travel, discussions, mechanization, automobilization, crowding, complications, despair-hope, reflection, concentration, welding, words, assembly, risks, hope, decision, confusion.” The machine, a huge phallic monument more than ten meters tall, had been hidden all day long, concealed by a purple drape, and was revealed only around ten o’clock in the evening. Then, after a short time, it began to move, to start its own self-destruction in the smoke and roar of the fireworks that set the Milan sky ablaze, covered the voices, and surprised the eight thousand people present, witnesses to the huge, thunderous suicide. The last fires would go off around eleven twenty, the machine was destroyed, the great phallus would lose its power, lose its dominance, and the last flames of the monument would be extinguished by firemen around two in the morning. Tinguely would later also thank the pigeons in the Piazza del Duomo for flying as the Victory self-destructed. Nouveau Réalisme, in fact, had already been at a standstill for several years (the movement’s last group exhibition had been organized in 1963), but on that tenth anniversary, the artists of the group had decided to see each other all in Milan for one last, final show, a sort of farewell tour with one stop, after which each would continue his or her career on his or her own. Christo had packed the monument to Vittorio Emanuele in Piazza del Duomo, Rotella set about tearing down posters in front of everyone, Niki de Saint-Phalle shot, Dufrêne declaimed, and so on.

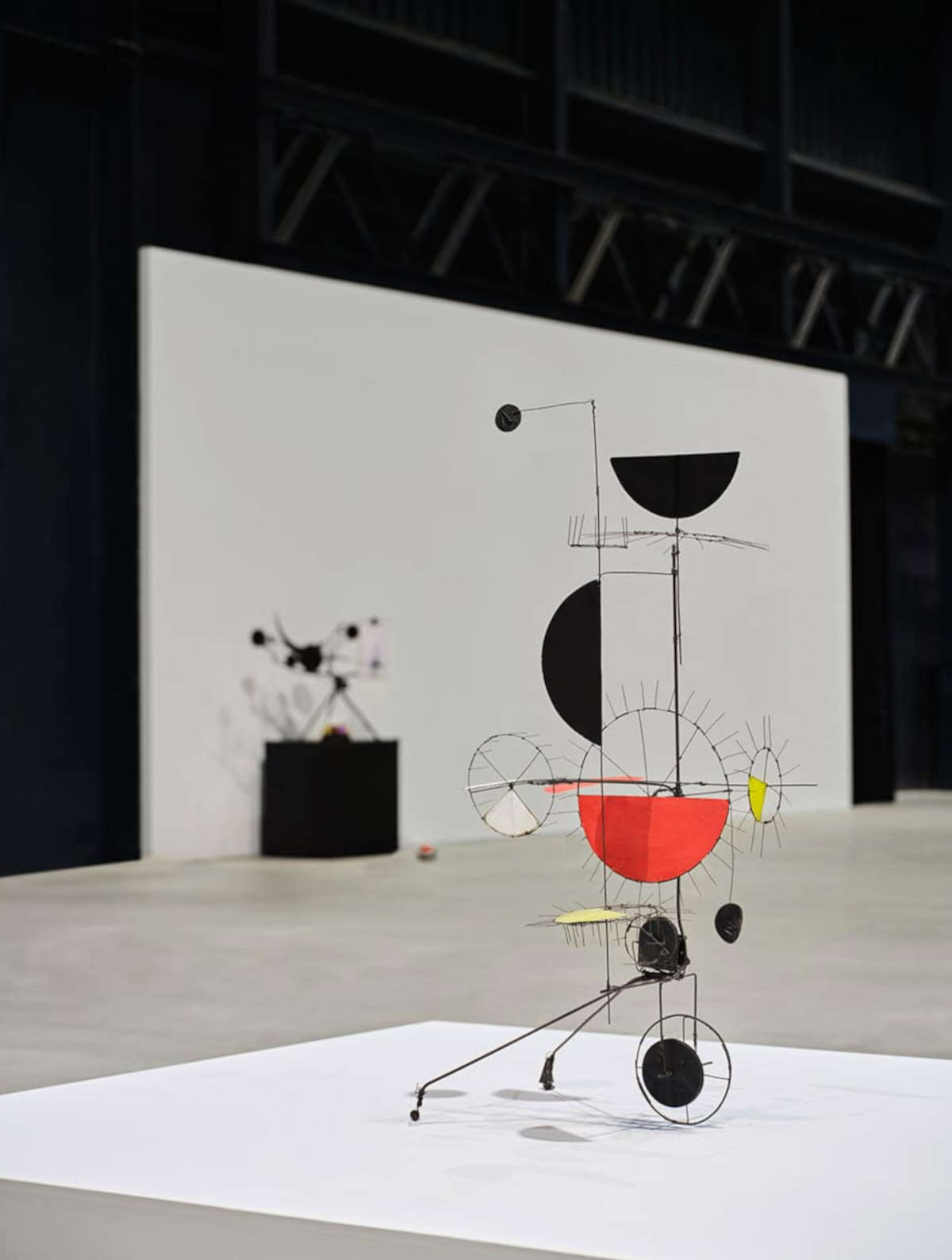

Victory, the climax of those three days, also marks the closing moment of the exhibition that, this year, the Hangar Bicocca in Milan dedicates to Jean Tinguely: it is the first retrospective to open in Italy after the artist’s death. The last opportunity for the Italian public to meet Tinguely had been in 1987, first in Venice and then in Turin, while the first was in 1954, in Milan. Seventy years ago to be exact: it was Bruno Munari who had invited Tinguely to bring his first machines to Studio d’Architettura B24, and Milan had been a pioneer, since the Swiss artist had previously exhibited his Méta-mécaniques only once, that same year, at Galerie Arnaud in Paris. To enter Tinguely’s world, therefore, one must begin visiting the exhibition not from the first machines one encounters (the tour is not organized chronologically: the layout is scenographic), but from a little further on, from a group of three sculptures(Sculpture méta-mécanique automobile, Méta-Herbin , and Trycicle) that offer the visitor a chance to measure himself against Tinguely’s early research. For at least a couple of years, the artist, as soon as he arrived in Paris, had been rummaging through the city’s suburbs for pieces of iron and metal that were no longer of any use to anyone or anything, and then taking them to his studio, assembling and painting them, and thus giving form to his first Méta-mécaniques, as Pontus Hultén would have advised calling them, to suggest a form of expression that has the same analogy with mechanics as physics has with metaphysics, namely, something capable of going beyond what one would expect from a machine: machines, in other words, are made to follow an order, rules, to be precise, reliable, hopefully efficient. Instead, the starting point of Tinguely’s research is mechanical disorder: his assemblages do not respond to any predetermined order. The only law that dominates his Méta-mécaniques is the law of chaos; his objects are improvised, they move without a defined purpose, they are essentially free.

Tinguely was not the first kinetic artist in history, others had preceded him: he, however, has the intuition to make human and machine collaborate in order to mix, transform, and revise the vocabulary from which he had started, that of the early twentieth-century avant-gardes(Méta-Herbin also bears in its title an homage to Auguste Herbin: the same Tinguely had done for Kandinsky, Malevic, and other avant-gardists) to create not machines or even sculptures, but paintings animated by electric motors, because that is how they were seen by the first critics who saw his works: the Méta-mécaniques were likened more to paintings than to sculptures.

Reflection on the machine is therefore central from the outset in Tinguely’s research. What is a machine? What can a machine do? What is the relationship between human being and machine? “Tinguely’s self-destructive and self-creative machines,” Hultén wrote in 1968, “are among the most engaging ideas of a machine society [...]. If art is a reflection on the fundamental ideas of a civilization, few images, few symbols are more pertinent than these machines, which have the richness and beauty of all the simplest, and therefore greatest, inventions.” The first “tentacle at the heart of our civilization,” as Hultén called it, were the Méta-matic, the machines for creating works of art, designed by Tinguely in the late 1950s. An example can also be found at the Milan exhibition: it is the Méta-matic no. 10, a machine that paints. At Hangar Bicocca you can activate it: you buy a 5 euro token at the ticket office, and with the help of an attendant who loads the colors on the machine you can operate it and take home the abstract painting made by the contraption: "Come and create your painting with spirit, fury or elegance, with Tinguely’s Méta-matics , the sculptures that paint!": so said the invitation to the 1959 exhibition in which the artist exhibited for the first time these unusual devices, these bizarre contraptions that nonetheless had a purpose, that of delivering to the public works of art created, perhaps for the first time in history, by an object that moved on its own, and the only human action required was simply that necessary to activate the device. The public at the Galerie Iris Clert in Paris, where Tinguely had first exhibited the art machines, had witnessed a reversal: in an industrial society that designs machines for the purpose of creating mass products that are all the same, Tinguely was designing one whose outcome was an ever-changing painting, personalized according to the tastes of the person who operated it. Interesting, amusing even, like most of Tinguely’s machines, whose playful aspect sometimes overrides other dimensions (look at the Maschinenbar on display and note the attitude of the children toward it): hard to perceive them as threatening. And yet, perhaps even a little disturbing: the artist was perhaps already foreshadowing a future of increasingly intelligent machines, capable of replacing human beings even in the production of expressive products typical of our creativity, or perhaps he believed that, in a society that tends toward standardization and homogenization, even art could become the product of a machine. However, Tinguely had a slightly different perception of his sculpture capable of producing works of art. “The painting machine,” Hultén sentenced in the 1987 Venetian exhibition catalog, "is an invention of fundamental importance and difficult perception, comparable to Marcel Duchamp’s ready-made . Méta-matics like the ready-made are divorced from any particular artistic style. Although the drawings produced by the Méta-matics ironically recall tachisme (blobs and patches of color arranged on the canvas without constructive intentionality), a dominant movement in Paris in 1959, this is not their main characteristic. Rather, it is a new way of approaching reality; they are the object of metaphysical meditation. Méta-matics get to the very essence of our civilization because they harmonize the relationship between human being and machine. Together they can create something irrational and nonfunctional, vital and creative. ’For me,’ says Tinguely, ’the machine is first of all a tool to succeed in being poetic. If you respect machines and enter into their spirit, you may be able to make a joyful machine, and by joyful I mean free. Isn’t that a wonderful possibility?’"

![Jean Tinguely, Méta-Matic No. 10 (1959 [Replica, 2024]; Iron tripod, metal plate and bars, wooden wheels, rubber belts, black paint, electric motor, 84 x 118 x 61 cm; Basel, Museum Tinguely). © Jean Tinguely by SIAE, 2024. Photo: Agostino Osio Jean Tinguely, Méta-Matic No. 10 (1959 [Replica, 2024]; Iron tripod, metal plate and bars, wooden wheels, rubber belts, black paint, electric motor, 84 x 118 x 61 cm; Basel, Museum Tinguely). © Jean Tinguely by SIAE, 2024. Photo: Agostino Osio](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2900/jean-tinguely-meta-matic-no-10.jpg)

There is perhaps no question related to the society of machines that Tinguely did not probe. And in this sense the Milan exhibition displays a very representative sampling of his works. Representative and all in all complete: the rare gaps (it would have been nice to see on display, for example, the spectacular Grosse Méta-Maxi-Utopia, or the enormous machine that Tinguely put together for the 1987 Palazzo Grassi exhibition in Venice, inside which one can even walk around) we imagine are mostly due to technical issues, since Tinguely’s machines are fragile objects, another characteristic that inevitably bumps up against our imagery, since we would expect his imposing metal machines to be strong, sturdy, durable. No: Tinguely’s machines are delicate. They suffer wear and tear, they suffer the indignities of passing time, many can no longer be put to work, and the Méta-matic itself no. 10 is in the exhibition with a faithful replica built this year. Others are stationary, but several are in operation, and in the exhibition they click off at twenty-minute intervals to create a freakish choreography: They start, move, beat, bang, strike, play, rattle, chime, chime, rattle, beat, smash, then one stops and the other begins, until the last one has finished its turn and in the hangar space silence again imposes itself (what place, then, could be better suited to host an exhibition on Tinguely than an old factory converted into an exhibition space?). Tinguely’s machines have no soul but seem to have one. Each has its own character, each has its own life, each, it was said, tells us about an aspect of the societies that produced them. With the Ballet des pauvres, Tinguely literally turns the traditional idea of sculpture upside down, hanging his objet trouvés from the ceiling and staging an eccentric, haphazard, disheveled ballet. The Baluba are wobbly sculptures that, in the artist’s own words, represent “that sort of madness and frenzy of today’s technological age”-the name is borrowed from that of the Central African people who, in the 1960s, with Patrice Lumumba, had succeeded in gaining Congo’s independence from Belgium. Tinguely had chosen to give this name to his confusing sculptures, with a mixture of irony and respect, because the epic of the Baluba had seemed interesting to him, a mixture of struggle and chaos such as the one the artist wanted to reproduce with his works, means to arouse in the public reactions of curiosity, surprise, distance, rejection, that is, the same reactions, opposite, that we still feel today regarding the society of technology. Then there is one of Tinguely’s best-known works, Rotozaza No. 2, a conveyor belt, activated in the exhibition a couple of times a week, that in a continuous cycle shatters glass bottles, sending them shattering (the audience is asked to stand at a distance so as not to be hit by the splinters): it is one of the most interesting examples of the dimension that Tinguely’s sculptures often take on, playful and dangerous at the same time, amusing and destructive, almost as if they had a temperament of their own (look at the machines of Plateau agriculturel as they move: they are painted in the typical red of agricultural machinery, and when they leave they almost look like characters dancing on the floor of a disco). There is a poetic work such as Requiem pour une feuille morte, where the whole imposing mechanism, a gigantic eleven-meter-wide machinery, is ironically put into action by a small white metal leaf, placed on the side of the work.

And then there are the works of Tinguely’s popularity, who from the 1970s onward became more and more of a celebrity and was able to steer his works in new directions, introducing, for example, the use of light, as is the case in the lamps that come toward the end of the exhibition, or operating on a vast scale: The two works that open the visitor’s itinerary, namely Cercle et carré-éclatès and Méta-Maxi, are a demonstration of this, works that expand Tinguely’s investigations into movement and sound (curious to note the stuffed puppets that sprout from the jaws of Méta-Maxi: it will be seen, later, that in Tinguely masculinity, brutality, and delicacy often coexist), up to those works that, more than others, certify Tinguely’s success: Pit-Stop, for example, was commissioned by Renault, and is made out of pieces of the Renault RE40 Formula 1 cars driven in the 1983 world championship by Alain Prost and Eddie Cheever (the car has the appearance of a large robot from whose arms clips of race footage of the two drivers depart: this is, moreover, Tinguely’s only machine that projects films), or Café Kyoto, a project for the café of the same name in Kyoto, Japan, for which the artist made lamps, tables, and seats. The work that closes the exhibition, however, is dense, unusual, as well as fundamental for understanding an aspect that is anything but secondary to Jean Tinguely’s poetics: the visitor finds himself in the presence of a bizarre, shimmering, mushroom-like tree, a tree with a double face, rigid and dark in front, soft, sinuous and white behind. It is Le Champignon magique, one of the last fruits of the collaboration between Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle, his wife: the two married in 1971 and remained united to the end, until Tinguely’s death that occurred in 1991. Magic Mushroom is from two years earlier, Jean’s part is done with his typical mechanical assemblages, while Niki’s is nothing’nothing more than one of his Nanas, his voluminous, maternal, reassuring women, covered with mirror mosaics like the large sculptures he designed for the Tarot Garden in Capalbio (those who visit the exhibition on Jean Tinguely cannot miss the simultaneous review on Niki de Saint Phalle at Mudec: it is also useful and important for reading Tinguely’s work in perspective).

It is clear that in the tree that Jean and Niki designed together coexist the natural, Edenic, timeless dimension of Niki de Saint Phalle and, at the same time, the artificial, mechanical, technological dimension of Jean Tinguely: the ambiguous dialectic between nature and culture that underpins Tinguely’s research emerges powerful, clear, overflowing precisely in the work that closes the exhibition, a work in which the masculine principle that governs Tinguely’s art, and which at times can appear even brutal, violent, prevaricating, is made manifest in all its evidence, if only because we notice it by contrast. However, it has also been said that it is difficult to deny the playful, ironic, sometimes even benevolent element of the machines of Tinguely, an artist who nurtured a certain faith in progress, a modern, and inevitably faded, reflection of the nineteenth-century belief that machines would guarantee humanity a bright future, a future that will redeem human beings from toil, pain and suffering because it will be machines that will work for us, that will relieve us of our most unbearable burdens, it will be machines that will transport us to a new golden age, to a new harmony with nature. There is a dialectic in Tinguely’s work: the artist exalts the machine, he exalts the artificial, he exalts the ability of the human being to preside over the domain of technology, but he is also aware of the violence to which the machine can tend, he is well aware of the brutality that lies behind the gears, behind the arms, behind the conveyor belts. Tinguely was 15 years old when World War II broke out: although Switzerland had remained distant from the war events (there was no shortage of accidents and some bombing, however, even in Basel, the city where Tinguely lived as a boy, and where today, moreover, the museum dedicated to him is located), theecho of the conflict was felt in all its violence (Tinguely moreover also matured, in 1939, the decision to join the resistance of Albania against fascist aggression, but he was stopped at the border and sent home because of his very young age). Having suffered the Second World War thus meant, for Tinguely, that he was well aware of the idea of the destructive power of machines. And the artist repeatedly expressed the idea that machines should be more feminine.

In several interviews, Tinguely stated that he was deeply fascinated by Johann Jakob Bachofen’s Muterrecht , the first in-depth study of matriarchy, matrilineal succession, and maternal law. “He was from Basel the first person who wrote a book on matriarchy,” he once recalled in an interview. “In ancient times, all children were named after their mothers; paternity was not sought. Paternity is the beginning of fascism. [...] I am for the abolition of patriarchy. Women must respond [to the male] with another form of power, otherwise the world is screwed.” The often absurd, fragile, noisy, clumsy, unnecessarily complex appearance of Tinguely’s machines can then also be read as a refined, pointed, ironic critique against the obsession with control and possession that is typical of the male. Tinguely, with his machines, is the spokesperson for a vision of human progress linked to an idea of transformation that is based on a restless, strong energy that risks being alienating, reaffirming the principle of the male and consequently separating the human being from nature: nevertheless, he cannot distance himself from nature if he does not want to run the risk of self-destruction. From this vision, certainly shaped also by his closeness to Niki de Saint Phalle but nevertheless present, though perhaps less explicit, since his early research, emerges the idea of a space of interaction between human being and machine that is not based on domination: for Tinguely, technological society is a kind of second nature, an artificial matrix, an extension of us that humanity has built and that has redefined our relationship with the natural world. There is no turning back: technology is necessary for the survival of our civilization, and the artist was aware of this. The “magic mushroom” shows that there is indeed a dialectic between nature and technology, there is indeed a tension that opposes the benefits guaranteed by the machine to its destructive power, but there is also the possibility of an encounter, of a dialogue between nature and technology. Tinguely’s machines sometimes appear amusing perhaps because the artist wants to show that behind that threatening appearance, behind that disturbing rigidity, behind those hard and angular forms there also exist the premises for a reconciliation. In 1968, commenting on the Rotozaza No. 1 that Tinguely had made the year before, Hultén was at pains to point out that “because Tinguely loves machines, he hates to see them corrupted and dumbed down by ruthless exploitation and greed.” It is a thought that appears implicitly in Tinguely’s work even before the shared experience, professional and life, with Niki de Saint Phalle, which certainly helped to define and orient in a more markedly the assumptions already observed in his art, but even a year before they met, as we have seen, Tinguely’s first concern was to enter into the “spirit of the machine.” He never fully clarified what he meant, and to what extent that machine was to be “joyful,” but that magic mushroom assembled together with Niki de Saint Phalle, that Champignon magique may perhaps be helpful in removing some veils. At the dawn of the age of artificial intelligence, at the start of an era in which the role of the machine is once again central to public debate, Tinguely is a more contemporary artist than many of our contemporary artists.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.