The cramped exhibition spaces of the Palazzo della Meridiana in Genoa are not easy to manage in order to set up an exhibition within them: the risk of piling too many works on the walls due to the curators’ fear of creating an incomplete project is just around the corner, but this has not been the case for the current exhibition running until July 16, 2023, entitled Extraordinary and Everyday from Strozzi to Magnasco. Human Contradictions in the Eyes of Painters, curated by Agnese Marengo and Maurizio Romanengo. In fact, the two curators have chosen to shape a small exhibition with a little more than thirty works (the balanced quantity for these spaces in the opinion of the writer), arranged well apart on the walls to provide the visitor’s eye with the right space to admire them at their best, and also choosing to give uniformity of color to the arrangements in order to give prominence to the paintings and at the same time not to disturb the view with too many colors.

As can already be guessed from the title, the exhibition is built on opposites, and a different section is dedicated to each pair of opposites, five in all. These are opposites between sacred and profane, contrasting thematic juxtapositions that in the curators’ intent highlight through art the human contradictions of the society of the time. They range from lateMannerism still from the 16th century to the 18th century with paintings and drawings from the Genoese sphere mostly from private collections. And if the Genoese seventeenth century has been addressed by recent exhibitions, it is the curators’ goal to present this century here “in an intimate version, attentive to its varied expressions, from the textural naturalism imbued with light of Bernardo Strozzi to the genial and unmistakable painting of Grechetto, from the conscious Baroque of Domenico Piola to the humanity observed from life by the De Wael brothers, from the lyricism of Giovanni Andrea De Ferrari to the Caravaggesque notes of Luciano Borzone and Domenico Fiasella.”

Arrangements of

Arrangements of Set-ups of the exhibition Extraordinary and Everyday

Set-ups of the exhibition Extraordinary and Everyday Layouts of the exhibition Extraordinary and Everyday

Layouts of the exhibition Extraordinary and EverydayThe dichotomy that brings together “the grandiose and the insignificant, the mythical universe and the minimal detail, the mystery of the sacred and the everyday gesture” is Extraordinary and Everyday, which gives the title to both the entire exhibition and its first section.

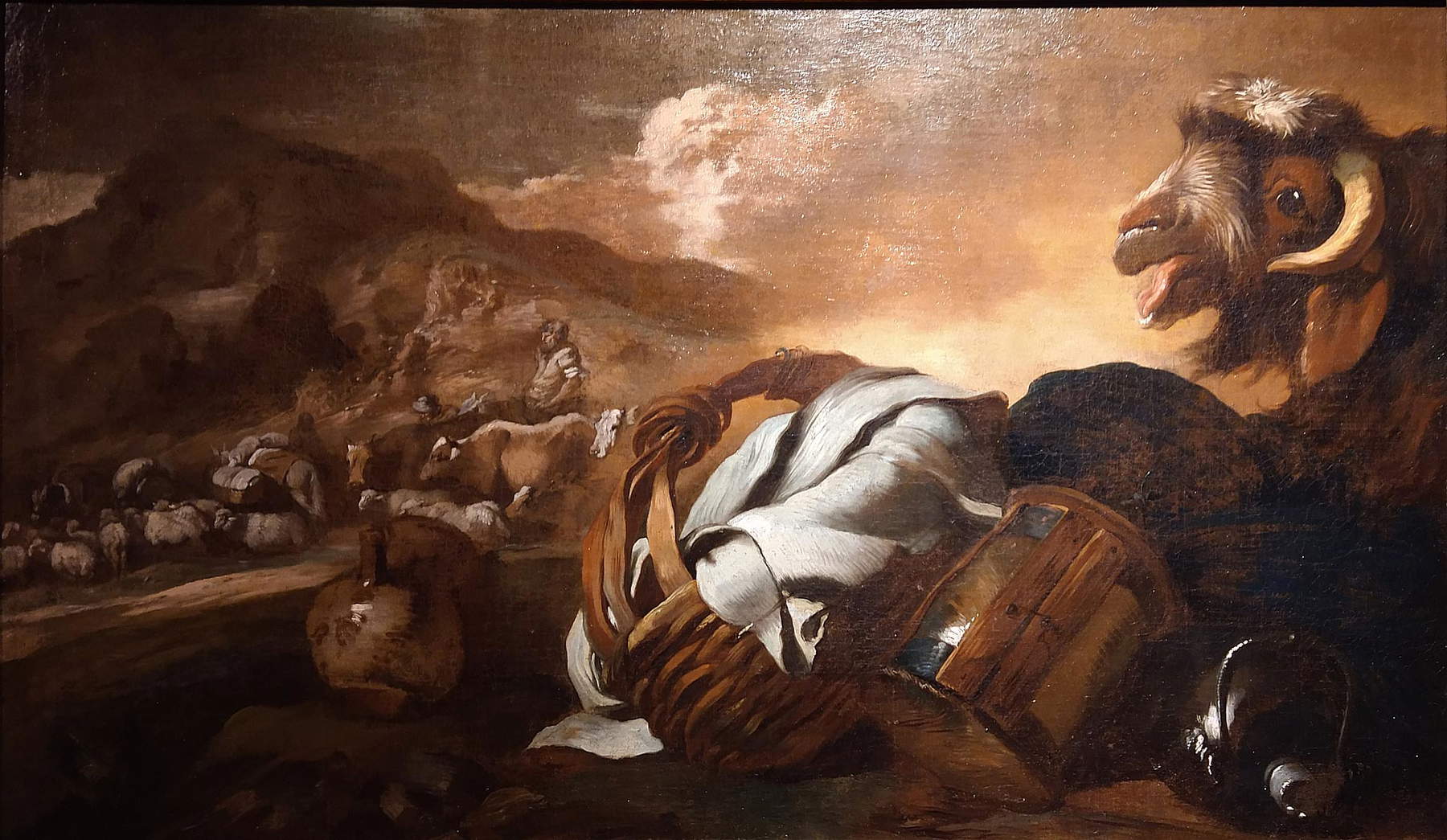

Constructing an exhibition about opposites seems to provide a simplified and universally understandable reading of art history, but actually on a deeper reading many of these works on display reveal iconographic particularities that make the exhibition interesting and intriguing and non-trivial. We begin with a pair of paintings by Grechetto, a pendant brought together for the first time for this exhibition: these are the Still Life with the Meeting of Abraham and Melchizedek and the Still Life with the Journey of Jacob’s Children in the background. In both, the everyday of the still life is placed in the foreground, while the extraordinary, that is, the biblical event, is placed in the background, so to decipher the episode in the background the visitor is invited to a deeper reading. Indeed, within the paintings are two inscriptions that refer to the Genesis passages referred to: chapter XIIII, or Abraham’s meeting with Melchizedek, and chapter XLII, or the return of Jacob’s sons to Canaan. In a landscape that seems to be uninterrupted in the two paintings, in the first Grechetto sketches in the background the handshake between the leaders and places in the foreground the spoils consisting of armor, trumpets and chiseled jewelry; in the second, the caravan of Jacob’s sons is hinted at in the background, while in the foreground are a lantern alluding to the night, a goat, a pitcher and a flask alluding to famine, and the money hidden in the basket.

In Bernardo Strozzi ’sAnnunciation, the extraordinary of the sacred event is inserted into the everyday of an interior that is suggested only by the chair-kneeler and the basket in the foreground with cloths; all around are clouds and light from which angels, God the Father, and the dove of the Holy Spirit look out. The scene, however, represents not only an Annunciation, but the moment of theIncarnation following the announcement. This can be perceived from Mary’s attitude, who seems already aware of the divine conception, from the swollen robe over her belly, and from the archangel Gabriel who does not point to heaven but is kneeling in a pose of devotion.

The Madonna in Sinibaldo Scorza ’s drawing becomes a mother who helps her young son take his first steps, aided by his little cousin, the St. John, in a scene that recounts the everydayness of life. And again, the Rest during the Flight into Egypt in Domenico Piola ’s drawing seems to be set not in an exotic landscape but in the garden of a villa of delight. Finally, Piola himself in the Wedding at Cana introduces a noble everydayness into the gospel wedding scene: the orchestra playing under the canopy, the silver plates, the monkey joking with the dog, the young servant waiting for instructions from the table master.

Bernardo

Bernardo

The second room accessed is dedicated to the dichotomy Misery and Nobility, expressed in two large paintings with a sacred theme: theAdoration of the Magi by Andrea Semino and theAdoration of the Shepherds attributed to Bernardo Strozzi. Semino brings together in his work both the poverty of the Holy Family, depicted under a thatched-roof hut, and the pomp of the Magi’s fabrics and gifts. The horsemen and dromedaries of the Magi’s procession are then glimpsed in the background, while between the background and the foreground are depicted three characters who belong to another era, as they are dressed in late 16th-century fashion, documenting the painter’s skill as a portraitist. Semino’s painting is counterbalanced by the previously unseen Adoration attributed to Strozzi’s early maturity set in a ruin with crumbling columns: here the focus is on the Infant Jesus, but if in the other work it is the rich robes of the Magi that stand out, particularly the one kneeling in the foreground, in this Adoration it is the play of reflections and light that captures the eye.

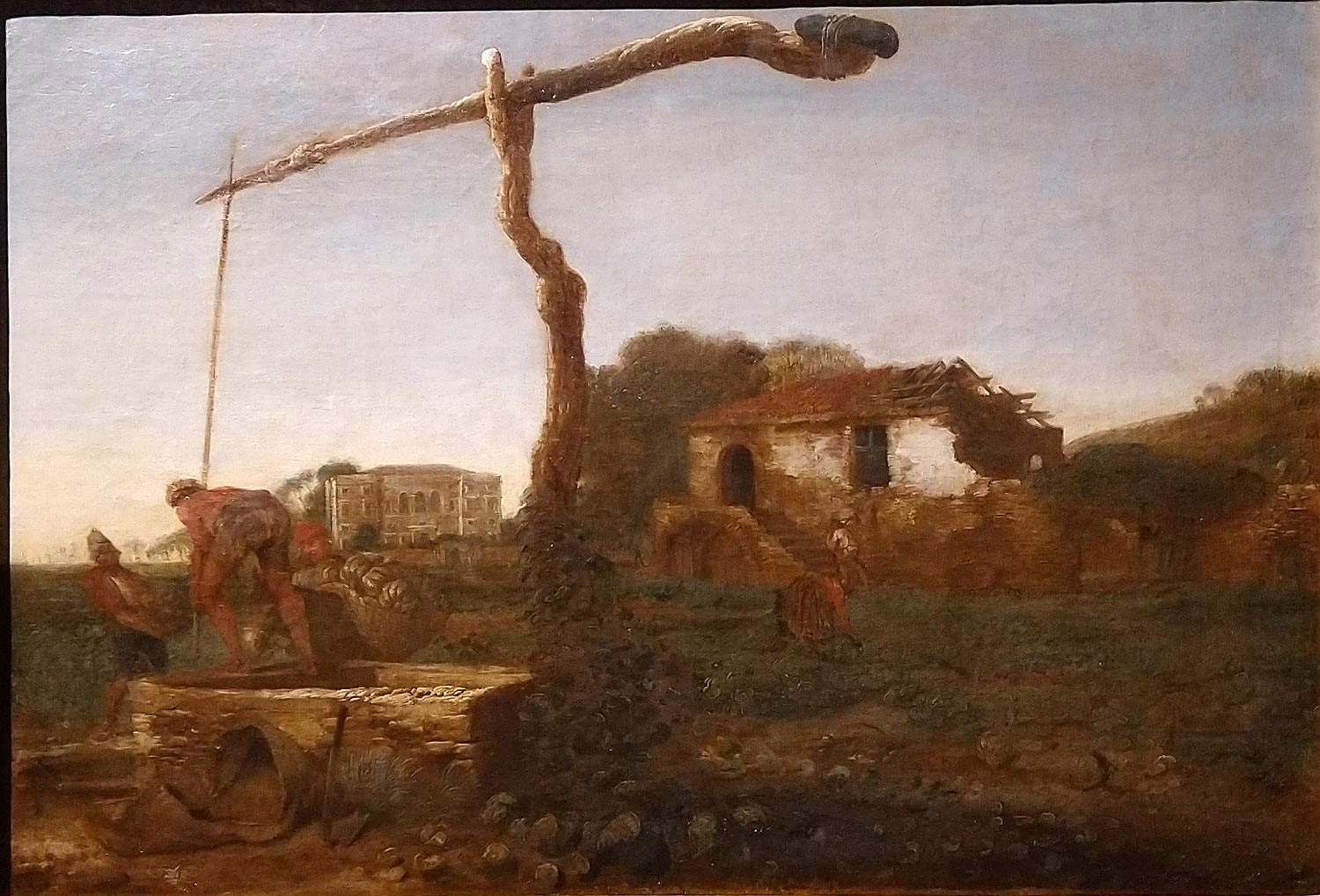

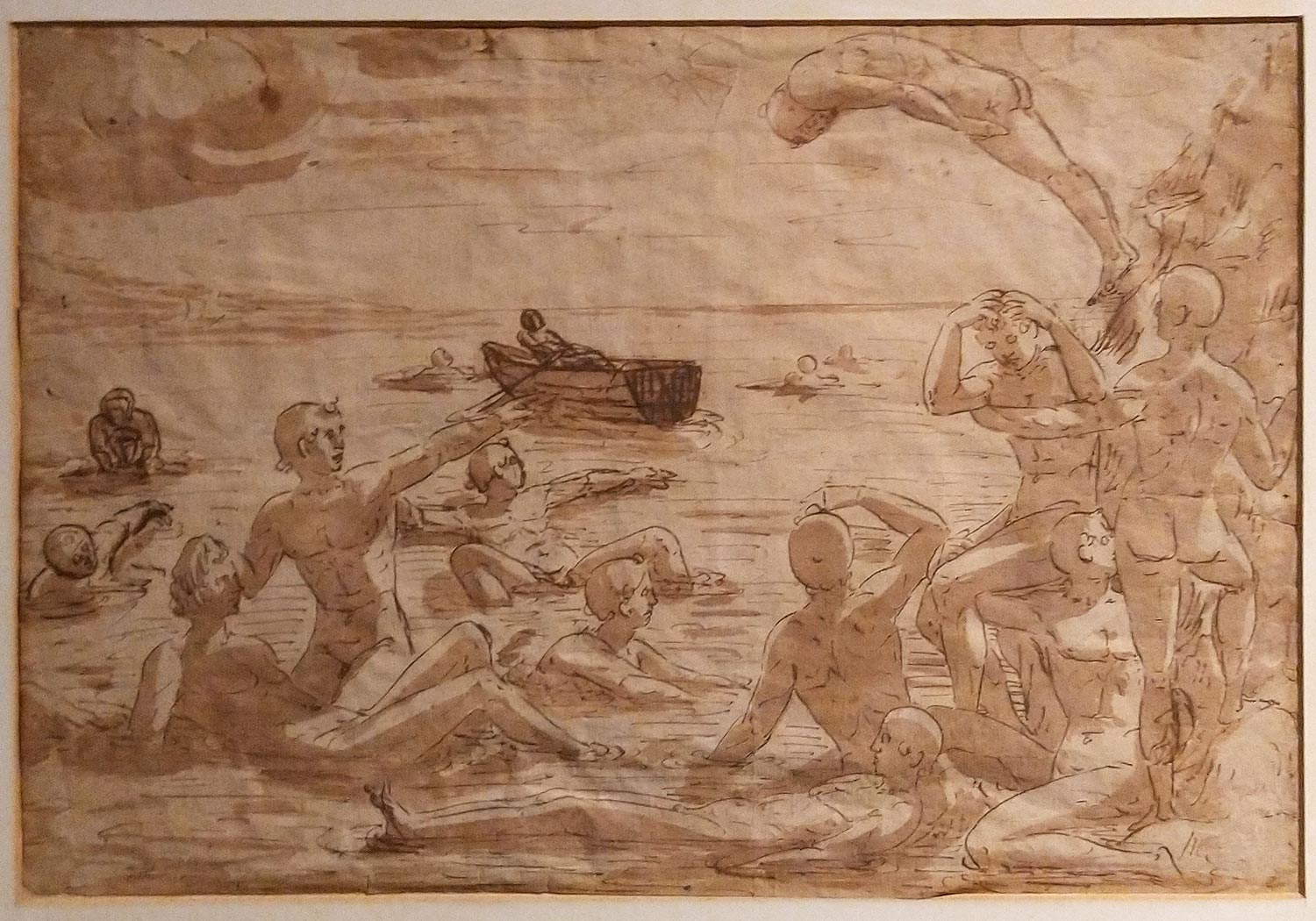

Next comes the section Idleness and Shop: the Genoese were notoriously dedicated to trade, especially in money. Holding economic and political power was thearistocracy, patrons also of art of the highest order, and it was in the gardens of their villas and mansions that those moments of “leisure” and idleness often depicted in painting were held, as in Lucas de Wael ’s painting in which in the scenic garden of a villa, of which the outline can barely be seen on the left, gentlewomen and gentlemen entertain themselves amid chatter and music. Idleness and store are, however, well represented in the Landscape with Peasants Picking Gourds by Antonio Travi, a pupil of Bernardo Strozzi, where the contrast is expressed by peasants at work in the foreground and a rich manor house in the background. The garden or countryside can thus be a place of entertainment or work ( Anton Maria Vassallo ’s painting of the young god Apollo intent on milking a cow in a bucolic landscape is also particular), as is the sea, which is also a place of activity, especially commerce but also moments of respite from work: Examples are Cornelis de Wael ’sMerry Brigade in which a group of men are depicted picnicking on the rocks after a swim accompanied by music, or the unpublished painting by the same author with a group of slaves and merchants at the harbor quenching their thirst and refreshing themselves by wetting their faces at the fountain. A scene of idleness by the sea is also depicted in the unusual and unpublished drawing by an unknown 16th-century artist active in Genoa that has naked men bathing in the sea and one even taking a dip. The section closes with a niche devoted to Alessandro Magnasco and his way of presenting the daily occupations of friars and nuns, the former grinders, the latter spinners; both absorbed in work and prayer, observing the rules of poverty and devotion.

Idleness as a game, especially with cards, expresses a sinful aspect in the section devoted to the dichotomy of saints and sinners: the old man in a shirt in Luciano Borzone ’s The Card Players has just lost his jacket playing cards against young boys who have probably tricked him (one is even making a vulgar gesture at him). It is a scene that seems to be taken from the picaresque genre that was widespread throughout Europe starting in the early decades of the seventeenth century and features scoundrels and wasters. Magnasco, too, depicts in the painting on display in the exhibition picaros, characters who appear to be unsavory, playing cards. These are flanked by religious subjects that, as the curators explain, “had at their core a short circuit between justice and error, such as the murder performed by the righteous Judith” by Domenico Fiasella or “the expulsion of the innocent Agar by Abraham” by Giovanni Andrea De Ferrari. Both unpublished and both with a detail to highlight: as is often the case, De Ferrari inserts a still-life piece in his works to capture the viewer’s attention but above all to communicate the sense of the narrative; in this case, the terracotta flask given by Abraham to Hagar, which besides being a sign of his attentions to the woman, hints at their experience in the desert and the subsequent angelic intervention that will point Hagar to the source. Fiasella’s Judith is imbued with the Caravaggesque light, but note the severed head held by the hair, in which the curator sees the features of a young Fiasella in his thirties.

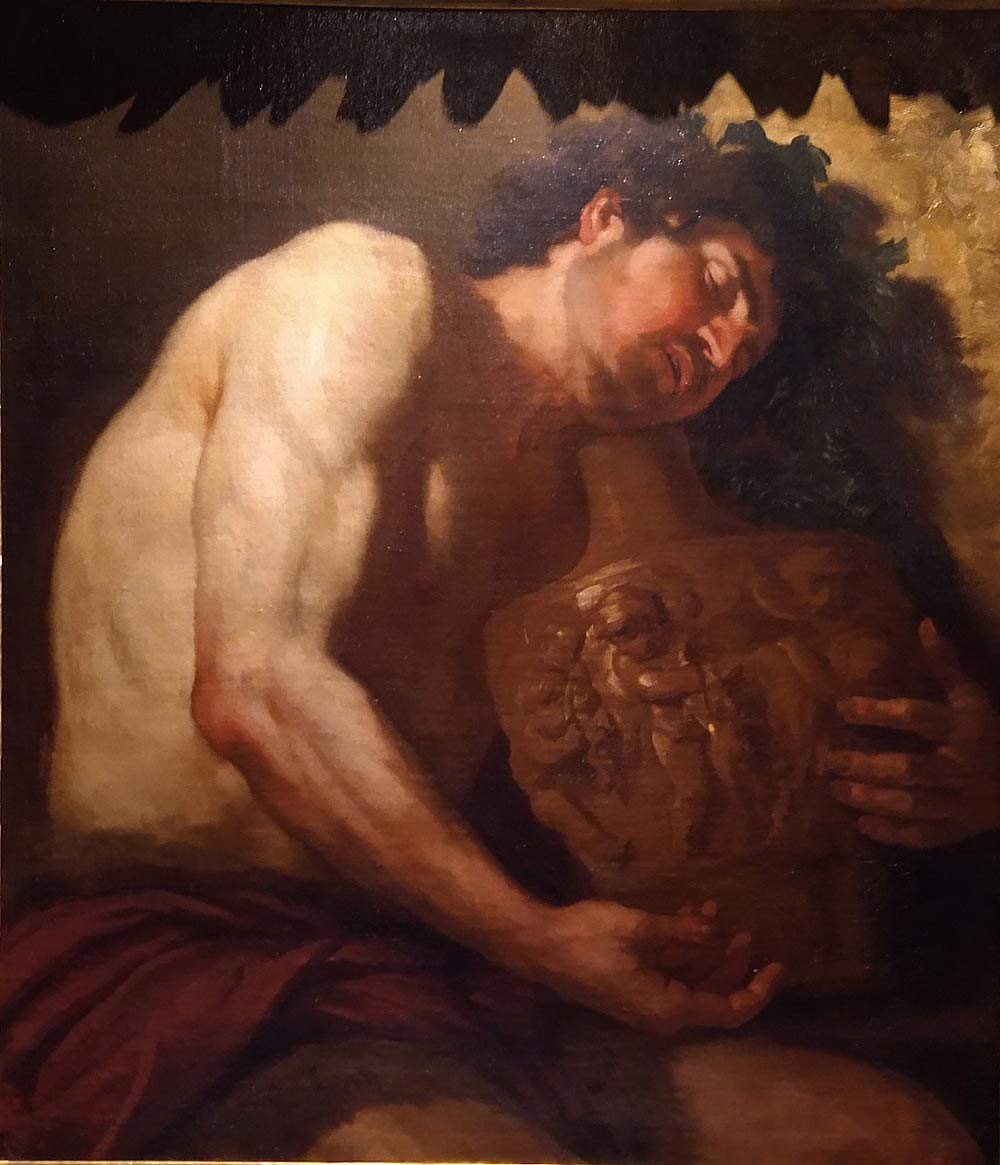

Finally, the fifth and final section focuses on portraits and nudes in the dichotomy Unveiled Bodies and Worn Clothes. It opens with Domenico Piola’s Portrait of Gerolamo Doria , in which the personage wears a richly decorated chamber gown, and the Portrait of Bianca Maria Carpineto by Giovanni Maria Delle Piane known as il Mulinaretto, to whom we acknowledge a certain taste for detailed description of clothing and accessories, and concludes with the unprecedented female nude of Antiope in Giove e Antiope by Gioacchino Assereto , which offers an uninhibited and new look at nudity at a time when it could only be found in Genoa in the affairs of the ancient gods, and with the clothed and sleeping Danae in Bartolomeo Guidobono ’s Jupiter and Danae , which is intended to be a “scholarly and ambiguous reflection on the nature of love.” The scene takes place under the foliage of a tree, and as Jupiter arrives and pours his shower of gold from a silver tray, the young woman is the only one who is not the least bit interested in it, unlike the old nurse, another young female figure, and a putto who impetuously picks up the gold at Danae’s feet. Also peculiar is Giovanni Battista Langetti ’s inebriated Bacchus, who depicts him with his head leaning against a wall while immersed in deep sleep and clutching a large flask of wine.

Returning to Assereto’s sensual Antiope, which has no such explicit precedent at that time in the particular depiction of the female figure from behind, Giacomo Montanari writes in the work’s file that there is to consider that in 1649 Diego Velázquez passed through Genoa for the second time on his way to Rome. And it was in Rome that he would have painted the Venus in the Mirror in the National Gallery in London, in which we recognize the same solutions offered in the Genoese displayed in the exhibition. Perhaps Velázquez may have seen Assereto’s painting in his 1649 Genoese passage, but no documentary source so far attests to the hypothesis.

Thus ends the small exhibition at the Palazzo della Meridiana, which, as it turns out, offers the public quite a few special features. A must-see exhibition, accompanied by a complete catalog of the works’ cards, for an unusual look with many previously unpublished insights into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Genoa.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.