Pietrasanta's "almost Dalí": a useless exhibition with no head or tail

The name of Salvador DalÃ, who has entered the ranks of the greats of art history almost by popular acclaim, is one to use if, for an exhibition, you want to play it safe. Given, therefore, the abundant exhibition production that has made use of the Spanish surrealist’s works in recent years, it has become particularly difficult to find interesting and original exhibitions that contain the word “DalÔ in the title. And on Saturday yet another exhibition on Dalà opened in Pietrasanta: an opening anticipated by bombastic announcements in recent weeks that have painted the exhibition as the usual must-see and must-do event. I am usually wary of exhibitions around which this artificial aura of anticipation, surprise, expectation is created. Add to this the fact that Salvador DalÃ. Between Dream and Reality (this is the title of the exhibition) traveled halfway around the world before arriving in Pietrasanta, and that the organization is by a private entity in possession of a good number of prints and reproductions of works by the Spanish artist accustomed to touring the world as if they were members of a musical group required to present their latest record to their audience.

Precisely about the organizing company, which has its registered office in Cyprus and base of operations in Switzerland, an article came out a few years ago in the Guardian that made it clear how the"Dalà sculptures" actually have very little to do with our artist’s production: they were in fact modeled from his sketches and drawings, produced in hundreds of copies in all formats, in various materials, colors and sizes, and sold to art enthusiasts all over the world. To produce these artifacts, the Cypriot company relies on a foundry in Mendrisio, Italy, which also issues appropriate certificates of authenticity to assure the buyer of the goodness of the purchase. The point is that, we learn again from the Guardian piece but also from an article that appeared in March 2016 in La Stampa, according to the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalà (created by the artist himself in 1983 to promote his art) these are works that cannot be traced back to Salvador Dalà and cannot be interpreted as authentic works: they are nothing more than three-dimensional reworkings of two-dimensional works by the Spanish artist. “Almost DalÃ,” in short, which have the same connection with the Spanish artist that the David miniatures sold in the bookshops of the Uffizi and the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence have with Michelangelo: I certainly do not want to say that one should not buy such kinds of products, but when one buys something it is always good to understand fully what one is buying. I believe that all this is a necessary premise to make the viewer understand what he or she is going to encounter, because perhaps many people think that those works were created or at least seen by Salvador DalÃ: none of that. This, however, does not mean that even with good reproductions one cannot put on an interesting popularizing exhibition, and it was with the expectation, precisely, of finding a good project that would present DalÃ’s work and art to the public that I went to Pietrasanta on the very day of the opening. Too bad expectations were fiercely disappointed.

Let us begin by saying that an integral part of the exhibition is the display of five large bronze sculptures in the Piazza del Duomo. A sort of large DalÃan amusement park which, I premise as of now, constitutes the most interesting part of the exhibition, if only because a selection has been made, on a monumental scale, that allows one to investigate the main symbols of which Dalà made use for a good part of his artistic career, and because, in any case, it is also quite amusing to see a seven-meter Space Elephant arrive in the square of a Tuscan town. Then, if the sculptures are surrounded by the stalls of the local patron saint’s fair (in fact, the inauguration fell on the day following the feast day of the town’s patron saint), observing the Surrealist Pianoforte or the Woman on Fire against a backdrop of salami and caciotta cheese might even prove to be a totalizing experience for some. And so far, minus the side sausages, the exhibition can still be justified at least by purely decorative intentions. The real problems begin, however, when the visitor decides to approach the portal of the church of Sant’Agostino, inside which the rest of the exhibition has been set up.

|

| One of the sculptures in Piazza del Duomo against the backdrop of salami and caciotta cheese |

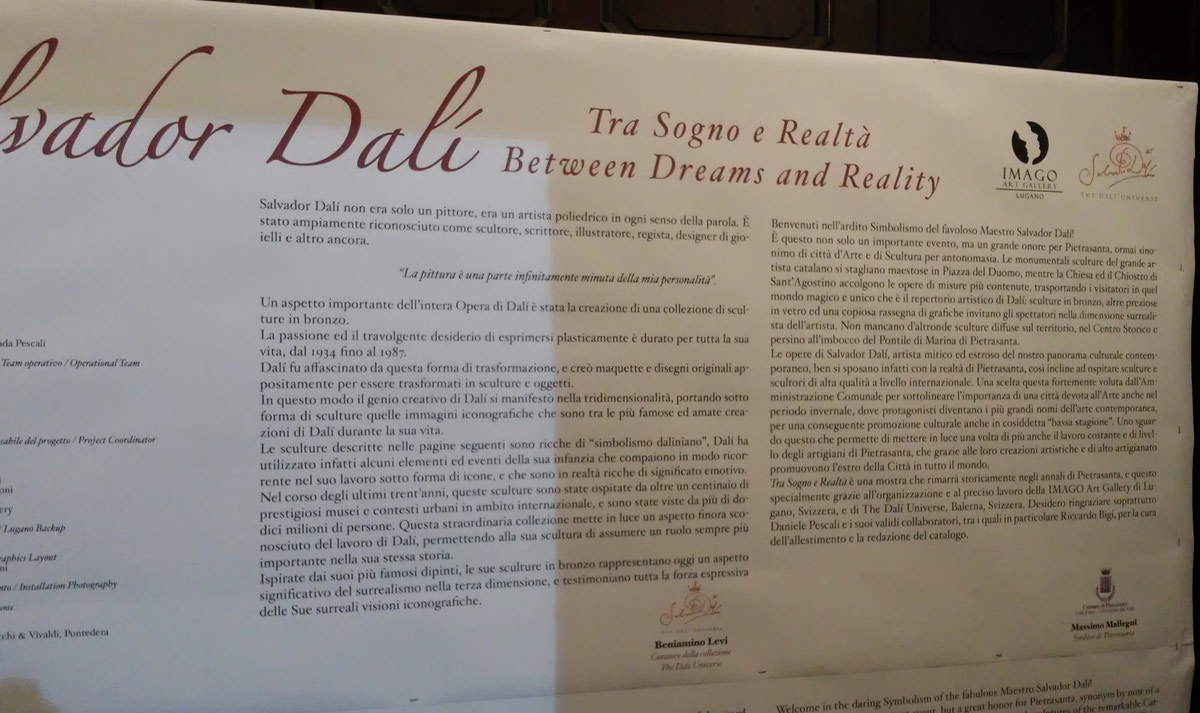

The writer has long wished for thetotal abolition of authority greetings from exhibition catalogs. The reader will therefore be able to guess with great ease my state of mind in observing that the right half of the exhibition’s introductory panel was affixed with the mayor’s welcome and, as if that were not enough, the left half was reserved for the speech of the owner of the company that sells the sculptures made from DalÃ’s works. Do not think, however, that such a presence induced me to leave prejudiced: I returned to read the panel only once I had left, because the throng of the public at the entrance (it should be emphasized that entrance to the exhibition is free) had prevented me from reading it. Past the small entrance vestibule, then, one finds oneself immersed in what could be considered the handbook of all that is museographically inappropriate. Beginning with the parades of lithographs juxtaposed by theme (the Carmen, the bullfight) without, however, an organic narrative, and even without captions identifying title, year of creation, technique, size, and whatnot. In short, all the information that should help the audience understand a work, in Salvador DalÃ. Between Dream and Reality are systematically eliminated: after all, given that the aestheticizing approach to art is what seems to be all the rage lately, what is the point of making the poor viewer understand what is going on in a work, why the artist chose a certain setting, who are the characters moving on the scene? Let the audience be content to say whether they like the lithograph in front of them or not! So, lithographs without titles, with explanations of the main themes entrusted to small, meager (but bilingual) panels, and sculptures that instead bear the explanatory signs, but placed at ankle height and drafted in tiny letters, so that one necessarily has to bend down to read them. Agreed that Dalà is considered a genius, but spurring the public to kneel before “reproductions of reproductions” of his works is perhaps a bit much.

|

| The exhibition in the worship-suspended church of Sant’Agostino in Pietrasanta |

|

| The introductory panel |

|

| Ankle height sign |

In the two cloister rooms, the music does not change. The green of the church’s panels gives way to a dazzling white on which untitled lithographs are again scattered, while in the center of the first room towers a second reproduction of the Surrealist Piano, which we find again, in a reduced format (and we still wonder for what bizarre reason the curator wanted to delight us with this work three times in the course of a single exhibition), in the last room. Here the visitor finds himself immersed in an almost complete selection of the corpus of sculptures taken from Salvador DalÃ’s works, reproduced in various shapes and sizes. In essence, the last room looks more like a kind of big Dalà souvenir store than a piece of a serious exhibition. Let’s not forget the usual lithographs decorating the walls, distributed probably at random: however, in this last room, it is not known for what reason, identification tags sometimes appear. Not for all the works, of course, that would be too much to ask, but every now and then one comes across such a fortunate presence, welcomed almost as a mystical apparition, so rare is it. After perusing the catalog (fifty euros for a kind of voluminous publicity leaflet from the organizing company, obviously entirely devoid of essays), leaving the exhibition cannot help but take on the appearance of liberation: far more useful and productive to launch into sipping an aperitif than to hurt oneself looking at a series of works that often have very little to do with DalÃ. However, this is not the main problem: one can create an interesting exhibition even with reproductions, or with works made from scratch from original drawings (and in any case, the first information that must be conveyed to the reader is surely the one that alerts him or her to the fact that he or she is dealing with works where the only intervention of the artist’s hand is the pencil signature on the prints). The problem is that the exhibition totally lacks a plan, it is a headless exhibition, the visitor leaves knowing nothing more about Dalà than he did at the entrance, and the whole thing takes on the appearance of a huge advertisement to the organizing company. Set up, however, in the context of a public space.

The advice then is only one: if you can, stay away from this indigestible and useless vaguely Dalinian meatloaf. Or, enter St. Augustine’s but to see the fragments of Zacchia da Vezzano ’s altarpiece and the works of seventeenth-century Tuscan artists that adorn the aisles of the church suspended from worship. And if you really want to cast a glance at the exhibition, do so if you want to see the sculptures live before you buy them. A note, finally, for the municipal administration: I wonder how appropriate it is to grant a public space of high importance to an exhibition that is not only devoid of any popularizing intent, but benefits the organizing company more than the host municipality or the visiting public. Although it is nothing new that behind the veneer of “art city” that Pietrasanta has cunningly constructed for itself in recent times there is, in reality, very little substance.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.