Lorenzo Lotto's portraits at the Pinacoteca di Brera

On April 19, 1543, Lorenzo Lotto (Venice, c. 1480 - Loreto, 1556/57) noted in his Book of Miscellaneous Expenses that he had received from “magnifico misser Febbo da Bressa,” “per parte de li contra scrittj sua retrattj,” the sum of “ducatj diece,” “that is, 60 lire in tanti mozanigi.” The sum that the noble Febo Bettignoli da Brescia paid to the painter was an advance payment of ten ducats, paid in “tanti mozanigi,” or “tante lire mocenigo” (the currency then current in the Republic of Venice), for a pair of portraits: that of the commissioner, and that of his wife Laura da Pola. The payments lasted until 1544: in all, the artist would receive for his services the sum of thirty ducats, plus "un par de paoni, " a pair of peacocks. A price that he did not consider satisfactory (“i qual denarj non paga el tempo sopra posto al’opera perso per acomodarlo”), but that in the end the painter accepted in order to keep his word to his client. Messer Febo da Brescia must have been particularly pleased with the painting, however (one would not otherwise explain the addition of the two peacocks given to the artist), and he had good reason to be, for we can assert without a shadow of a doubt that the pair constitutes one of the high points of Lorenzo Lotto’s portraiture. And that value is, moreover, underscored by their central position in the new layout of Room XIX of the Brera Art Gallery, the museum that received the portraits in 1860, when Victor Emmanuel II purchased them (along with the portrait known as the Gentleman with Gloves, about which more below) from their last owner, the Turin-based Count Castellane Harrach, to make a gift of them to the Milanese Academy. It can be said with some margin of safety that, throughout their history, the two paintings have never been separated: recorded as a pair since the first inventory of the Pola family’s property, which dates back to 1596, they are shown together even now, on the same wall, in the great Milanese picture gallery.

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, the portraits of Febo da Brescia and Laura da Pola |

|

| All Lorenzo Lotto’s portraits in the Pinacoteca di Brera |

They are portraits that are extremely communicative, as well as very truthful (and in their ability to adhere to their subject, perhaps Lorenzo Lotto was the greatest portraitist of the sixteenth century) and curated with skill and elegance, so much so that an art historian as well as a fine connoisseur like Gustavo Frizzoni believed that the three “Milanese” portraits represented the pinnacle of Lotto’s portraiture: “where the artist, in such a genre of painting, seems to have reached the greatest finesse and the best balance of his forces is in the three effigies which, through the munificence of Victor Emmanuel II, came about thirty years ago to the Brera Picture Gallery.” And more or less of the same opinion was the great Bernard Berenson, the scholar who, in 1895 (and thus a year before Frizzoni drafted his own commentary), had first succeeded in tracing the two Brera paintings back to the notes pinned by Lotto in the Libro di spese diverse: in that meaty essay, entitled Lorenzo Lotto: an essay in constructive art criticism and devoted entirely to the Venetian artist, Berenson had written that “both portraits are executed with skill and mastery, with delicacy of light and shadow, and with a subtle blending of tones, qualities that place them in a niche of their own within Lotto’s output.” And even for Berenson, “their only rival,” although he considered it “superior to them,” was “the portrait that stands between them at Brera, which is, morphologically and technically, so similar to them that the belonging of all three paintings to the same period may be taken for certain.” Moreover, today, fortunately, the “rival” has been moved, and the portraits of husband and wife are shown side by side without any “third wheel” to interpose.

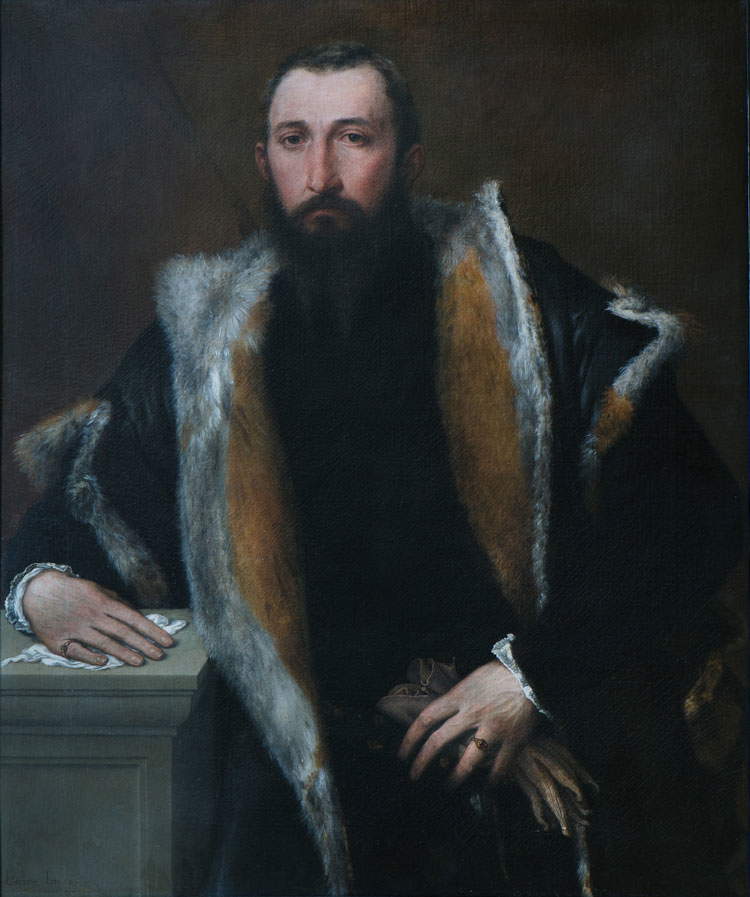

It is worth taking a closer look at the paintings in order to understand the reasons that led Frizzoni and Berenson to speak of finesse, balance, mastery, delicacy. The portrait of Febo Bettignoli, a member of an illustrious family of Brescian origin who had, however, long since moved to Treviso and had become part of the city’s nobility (it is worth remembering that Lorenzo Lotto’s favorite subjects, and probably the greatest to which he could aspire given his tormented artistic career, were precisely the lords of the small local nobility), appears to us in all its austere elegance: black is the traditional color of sobriety in clothing, but such a choice in dress does not prevent Febo Bettignoli from manifesting his status through the rich fur lining of his overcoat (which denotes a textural rendering that rivals Titian’s), the embroidery on his shirt cuffs, the ring on his right hand, and the wedding ring that instead adorns his left. It is precisely in the left hand, by the way, that the catalog of the major exhibition on Lorenzo Lotto held at the Doge’s Palace in Venice in 1953 singled out a “piece of extraordinary painting”: and it is not difficult to understand why, if one observes the admirable modeling, the tension of the veins and cartilage in the gesture of holding the gloves, the natural and balanced movement. But also remarkable is the piece of the right hand firmly holding the white handkerchief, which, just like the leather gloves, symbolizes the gentleman’s haughty detachment from the ugliness of the outside world (but it could also be a reference to marriage: the glove is a marital symbol, while the embroidered handkerchief could belong to the wife).

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of Febo Bettignoli da Brescia (1543-1544; oil on canvas, 90.5 x 75.5 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

If Messer Febo’s attitude and gaze simultaneously denote lordly confidence and measured composure, the portrait of Laura da Pola indulges in a few more vexatious licenses, if only because the looser her pose appears and the more pronounced her desire to show the viewer the agî that the Bettignoli and the Pola could boast, while not falling into an uninhibited ostentation that would have been ill accorded with the elegance that was considered proper to a high-ranking family: the display of the pearl necklace, the velvet gown decorated with a black diamond pattern, the vain ostrich feather fan with gold chain (indeed the only wholly frivolous object Laura da Pola carried: but its use was prevalent at the time in certain circles), the precious shoulder cover decorated, as well as the sash that the woman wears on her head, with floral motifs, the chain that clasps her waist, and the gem-studded rings is functional in communicating to the viewer her membership in one of the most prominent families of her city. However, these are not the only details to pay attention to. There are the draperies, green and red, which are responsible for creating an intimate and familiar setting. There is the furniture, a kneeler, which serves the same function and allows us to identify the room as a bedroom. There is the book that Laura da Pola carries in her manicured tapered hand: a prayer book, perhaps, since the young woman leans on the kneeler. Or a book of poetry, given the undoubtedly worldly tenor of the painting. And then there is the gaze of this girl caught in the prime of her twenty-three years. A fixed, almost lost gaze that does not meet that of the viewer. A gaze profoundly different from that of her husband. Laura da Pola is clearly absorbed in her own thoughts: there is a sort of disagreement between the girl’s face and the objects with which she has adorned herself, a disagreement that makes clear both the humanity of a girl who had married a man almost twice her age (he was seventeen years her senior) and Lorenzo Lotto’s superb capacity forpsychological introspection.

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of Laura da Pola (1543-1544; oil on canvas, 90 x 75 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

It was mentioned above how, in the past, another painting of enormous value stood between the portraits of the couple: the aforementioned Gentleman with Gloves, which we see today alongside Laura da Pola. Consequently, the latter part of its story continues to be linked to that of the portraits of the two noblemen from Treviso. Although it is a signed painting (exactly like the portraits of Febo da Brescia and consort), we do not know on what occasion it was executed, nor do we know for sure who the effigy is. We only know that it was in the house of Count Castellane Harrach when Victor Emmanuel II bought it. However, we can speculate on the identity: in 1908 the art historian Francesco Malaguzzi Valeri, in compiling his catalog of the Pinacoteca di Brera, proposed identifying the Gentleman with the Whites with that “Liberal da Pinedel” whom Lorenzo Lotto mentioned in the Book of Miscellaneous Expenses (“Die dar misser Liberal da Pinedel per un suo retratto di naturale del quale non fu fatto alcun precio, ma starmi a quelle honestà che porta un gentiluomo, fornito el quadro valse a boni pretii ducati 20”). Since then there have been few reasons to question the identification proposed by Malaguzzi Valeri (one above all, the age of Liberale da Pinedel, who would have been forty-eight years old at the time of the portrait), but neither has any further supporting evidence emerged: consequently nowadays, with the usual caution that characterizes the actions of scholars in cases of this kind, we are inclined to accept dubiously that the old gentleman may be the Liberale da Pinidello (if one admits that “Pinedel” is the term in Venetian for the village near Conegliano) mentioned in the painter’s notes.

“It is the subtlest of all Lotto’s portraits in terms of characterization, and, considering it merely on a technical level, it is his highest achievement”: this is how Berenson spoke of it in the aforementioned essay on the artist. Scholars have always admired the extreme truthfulness and great intensity of this face painted through fine tonal passages, which enhance the melancholy expression of this man with a tawny beard: it almost seems as if the artist developed such empathy that he penetrated the character’s mind and empathized with his probably unhappy thoughts. This ability to read the subject’s soul almost overshadows the skill with which the artist renders the black robes of this man dressed even more soberly than the two young noblemen with whom he shares the wall at Brera (in fact, he appears to us encased in a broad black overcoat embroidered on his lapels: the only jewels are the ring on his index finger and the gold chain) and clutching in his hands the same objects with which Febo da Brescia was portrayed: again, the embroidered white handkerchief and the leather gloves.

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Gentleman with Gloves (Portrait of Liberale da Pinedel?) (1543?; oil on canvas, 90 x 75 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

The Pinacoteca di Brera houses one more portrait executed by the hand of Lorenzo Lotto. It is, however, the only one for which it is difficult even to formulate an identifying hypothesis. It is a Portrait of a Gentleman, which shares with the other three paintings by Braidense on the one hand the austerity and composed measure (here too we are dealing with a personage dressed entirely in black) and on the other hand the technical and stylistic proximity, so much so that it has been thought that it could be a work made more or less in the same period, that is, in the mid-1640s. If this were the case, however, the only proposal put forward to give a name to the personage would fall: it could in fact be, at least according to Mauro Lucco, who was the first to recently formulate the hypothesis, Giovanni Taurini da Montepulciano, still a notable mentioned in the Libro di spese diverse (“die dar el signor vice gerente de Ancona misser Joanni Taurino de Montepulzano per un quadro de suo ritrato di naturale dal mezo in suso, a tuta mia spesa tella, telar e colorj. Valse almancho scuti dodece”). This was a member of theentourage of Vincenzo de’ Nobili, who was a nephew of Pope Julius III and held the position of governor of Ancona for the Papal States. If we were to accept Lucco’s idea, however, we would have to postpone the dating, since the Book of Miscellaneous Expenses mentions a work executed in 1550.

The object the character holds in his left hand (it looks like the pommel of a sword) could symbolize his political office (Giovanni Taurini was vice-governor), but we cannot establish this with certainty: the references are too vague. And equally vague is the gesture of the right hand pointing to something outside the painting: we have no idea what the man is pointing to. Here, too, we have a careful study of expression, which denotes steadfastness and, partly by virtue of the heightened gestures, stands in direct dialogue with the viewer. This capacity for interpenetration is, after all, what Titian lacked, who had indeed renewed the typology of the official portrait (and here Lorenzo Lotto shows that he conforms, taking up the type of the standing portrait that the Cadore artist had inaugurated) but lacked the level of identification that distinguished Lotto’s portraiture.

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Gentleman (fifth decade of the 16th century; oil on canvas; 115 x 98 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

In addition to the four paintings mentioned above, until June 11, 2017, another portrait by Lorenzo Lotto is on display in Room XIX of the Pinacoteca, which arrives on loan from the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice for the “dialogue” Around Lotto held on the occasion of the room’s refurbishment. It is the Ritratto di gentiluomo di casa Rovero (Portrait of a Gentleman of the House of Rovero), so called because it was present, until 1923, in the collections of the Rovero family of Treviso, and since the relations between Lorenzo Lotto and an Alvise belonging to the family are documented, it has been thought that the effigy may be a member of the family, although we cannot with certainty ascertain which one it is. It is, in any case, an unusual work: both for the format chosen (horizontal instead of the more typical vertical format), for the many objects that crowd the scene, and for the symbolism that would be hidden behind the work. One can still read in the young man’s eyes a slight sense of melancholy, which one wanted to relate to what appears in what evidently seems to be his study: the abandonment of a life of excess, a love disappointment, or simply a particular character inclination. This is a painting that critics have dated to a period earlier than the one in which the Braidense portraits were executed (we speak of about 1530-1532), but it is no less effective in the psychological rendering of the subject and in the effective delineation of an “intimate biography” of the subject (so according to Maria Cristina Passoni, curator of Around Lotto together with Francesco Frangi): a dialogue that is therefore made particularly dense and timely.

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Gentleman of the House of Rovero (c. 1530-1532; oil on canvas, 97 x 110 cm; Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.