by Ilaria Baratta , published on 06/11/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Courbet and Nature' in Ferrara, Palazzo dei Diamanti, September 22, 2018 to January 6, 2019.

He is seen proud and self-confident, looking toward the viewer in an almost haughty attitude, in the company of his faithful dog, a black spaniel. It is Gustave Courbet (Ornans, 1819 - La Tour-de-Peilz, 1877) himself who is seated in the foreground, dressed in dandy attire: an elegant black redingote, white collar, and gray plaid pants testify to the high social class to which his family belonged, while the wide-brimmed black hat and curved walking stick protruding to the left of the painting refer to his habit of taking endless walks in the midst of nature. The long hair and pipe in his right hand declare him a member of the Parisian bohemian milieu, and the sketchbook placed behind indicates his activity as an outdoor painter, probably during frequent walks through the woods and valleys of his native Franche-Comté region.

In the background, in fact, a rock face can be glimpsed behind him and, further in the distance, a valley. In this painting, made in 1842 and now kept at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Courbet seems proud to be part of the scenery that surrounds him, which is none other than his homeland, and he reveals through his art a very significant part of his autobiography: his visceral bond with nature and especially with his native places.

And so it is Courbet himself who introduces visitors to the exhibition that Ferrara ’s Palazzo dei Diamanti dedicates to him until January 6, 2019, Courbet and Nature. As mentioned, he does so through his Self-Portrait, a genre little frequented by French artists until the mid-nineteenth century, but on the contrary practiced on several occasions by Courbet (between 1842 and 1855 he made about 20 of them), highlighting already in this aspect his revolutionary and countercultural character. Moreover, this is a particularly significant work in his pictorial activity, since it was, in 1844, the artist’s first canvas accepted at the Salon and thus the first public success of the barely 25-year-old painter. The landscapes in the painting, namely the rocky scenery, forests, and valleys typical of Franche-Comté, would never leave the painter’s soul: they would be found in countless paintings, including those set abroad during his sojourns. Each landscape he depicted becomes an autobiography, in which he invites the viewer to get to know the most intimate part of himself, beyond his strong character.

The uniqueness of his landscape art lies in his refusal to consider the surrounding nature and landscape as elements in their own right, but rather amalgamated and contextualized with the painter’s biography, as well as with the presence of depicted characters. Landscape and humans or animals are always mutually related. Even where there is no human or animal presence, as in the painting placed in the introductory room,depicting the Oak of Flagey, otherwise known as the Oak of Vercingetorix, one senses the autobiographical nature: the imposing oak depicted strongly welded to the ground feeds on the strength of the soil of Franche-Comté, as it does for Courbet himself. The presence, almost imperceptible compared to the majesty of the tree, of a dog chasing a hare, anticipates to the visitor his passion for hunting art, to which the last room of the exhibition has been dedicated, as we shall see. Moreover, the strong personality of the painter, who was revolutionary for his time, can be understood if we consider how landscape painting was marginal to artists before or contemporary to him: considered a minor genre by academics, Courbet made it rise to a significant motif of his art. Finally, Vercingetorix’s Oak takes on historical and once again revolutionary significance, as Napoleon III and his followers set the famous Battle of Alesia between the Gauls and Romans fought in 52 B.C. in Burgundy, while Courbet with this painting affirms his belief that the battle was fought in Franche-Comté: a doubt caused by the dispute between Alise Sainte-Reine, on the Côte d’Or, and Alaise near Flagey, in Franche-Comté.

|

| A room of the exhibition Courbet and Nature. |

|

| A room of the exhibition Courbet and nature. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room of the exhibition Courbet and nature. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room from the exhibition Courbet and Nature |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Self-Portrait with Black Dog (1842; oil on canvas, 46.5 x 55.5 cm; Paris, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Oak of Flagey (1864; oil on canvas, 89 x 111.5 cm; Ornans, Musée départemental Gustave Courbet) |

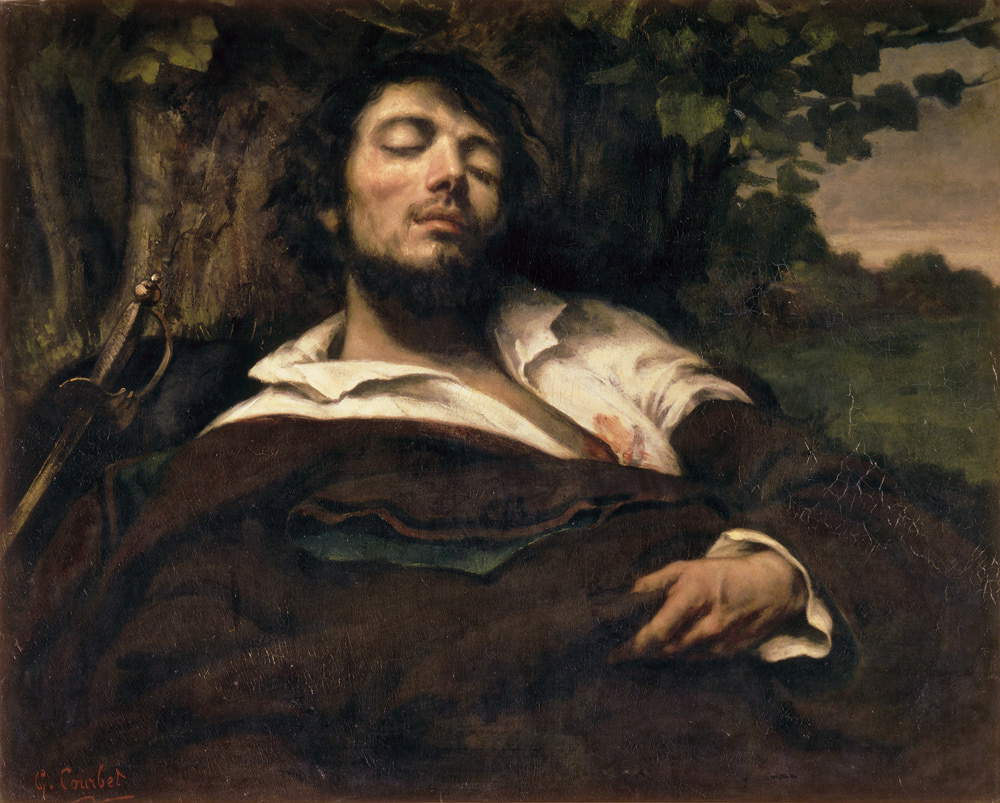

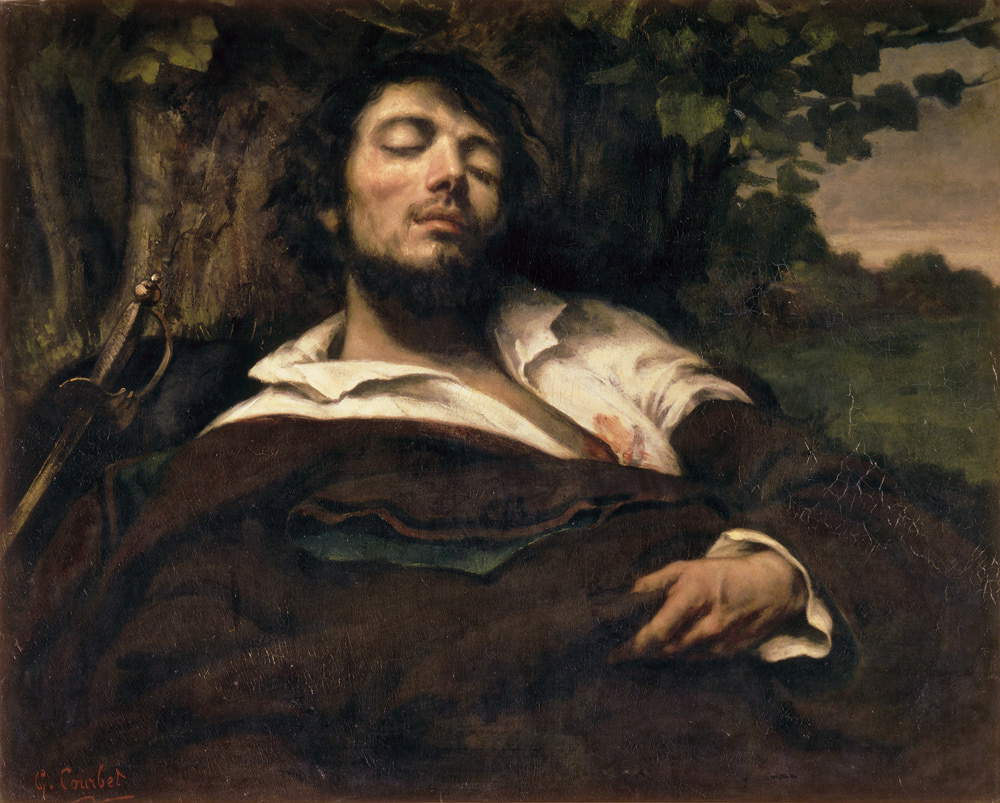

Continuing with the self-portraits, the visitor will find another in the next room, dedicated to “postcards” of Franche-Comté. It is The Wounded Man: in the foreground is Courbet himself, lying down and leaning against the trunk of a large tree, with his eyes closed and a wound on his chest, which has stained his white shirt held open with blood. A sword sticks out next to him. This is a painting heavily influenced by German and French Romanticism, as the X-ray showed the painter and his beloved in the foreground, tenderly slumbering and embracing. The present composition, the result of a modification by the artist himself, dates instead from 1854, when Courbet had discovered that his beloved and the mother of his son, Virginie Binet, had married Those depicted are therefore sentimental wounds.

That same year, addressing his friend and patron Alfred Bruyas, Courbet said that in his life he had made several portraits of himself, depending on his spiritual situation, so it was as if he had written his autobiography.

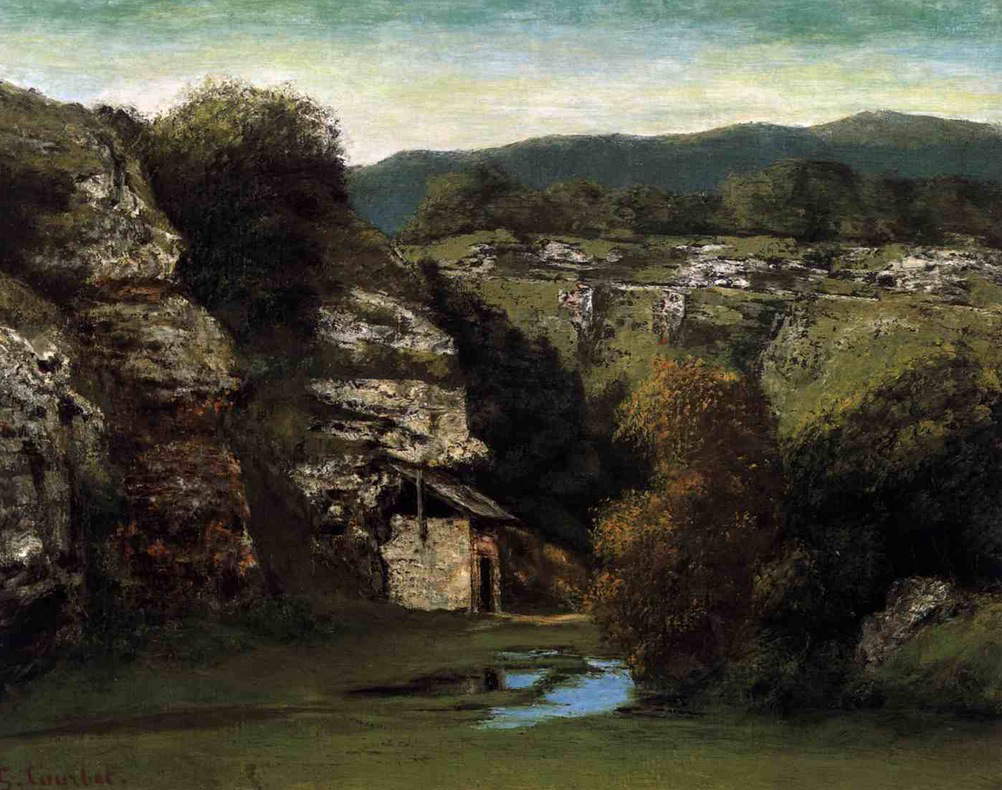

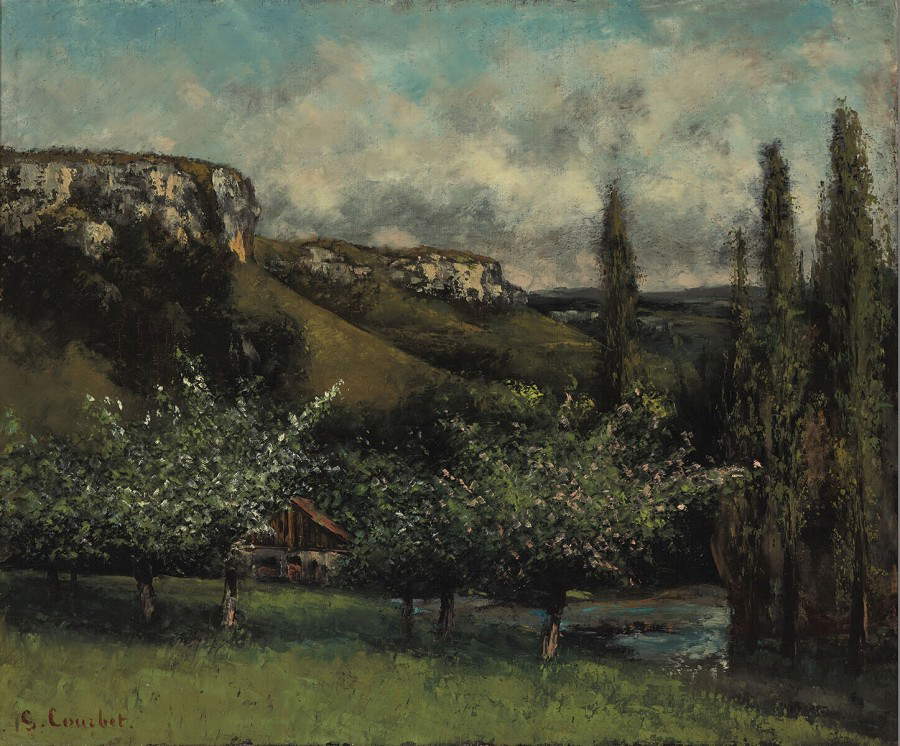

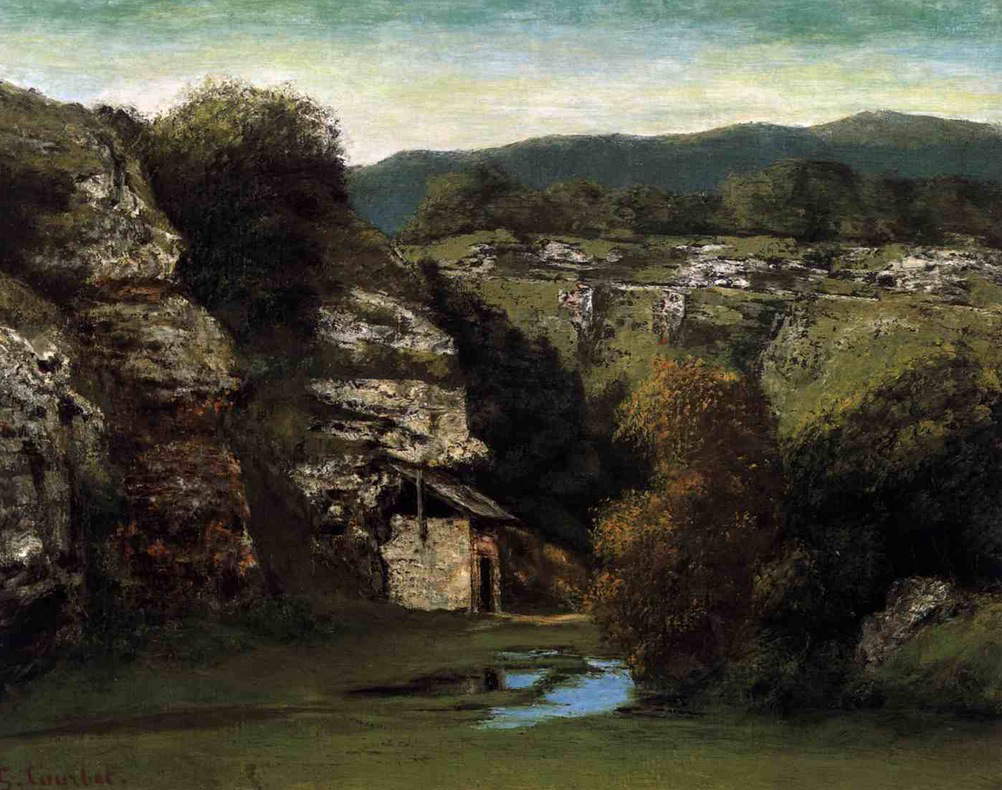

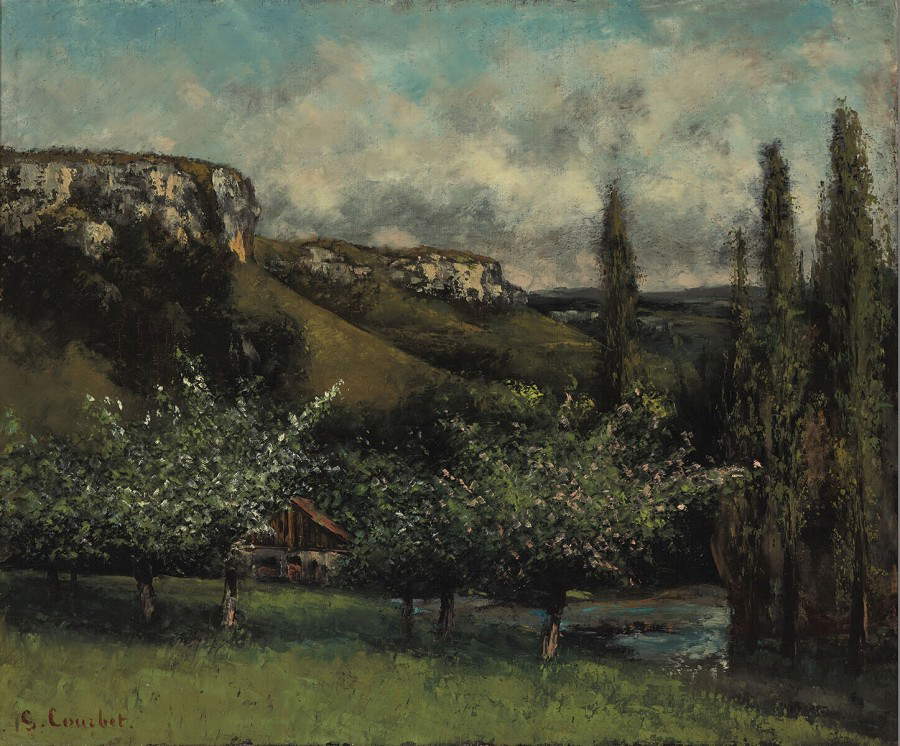

Proud of his homeland, the artist almost pronounced a maxim of his art: “To paint a landscape, one must know it. I know my country, I paint it.” Indeed, there are many paintings depicting Franche-Comté, and in this second room the visitor finds himself immersed in the most evocative scenery of this part of France, including forests, mountains, plateaus, rivers,valleys; a region fully dominated by nature. The first painting that can be considered the initiator of this theme is The Valley of the Loue under a Stormy Sky: present in the exhibition, the work fascinates because of its composition, as it is sharply cut into two distinct parts. In the lower part, the rocky element is linked to the woodland element, consisting of a rich variety of greens and browns that outline the profiles of the trees and shrubs; there are also, in the center, quite camouflaged in the surroundings, two human figures accompanied by a dog crouched behind them. The upper part of the work, on the other hand, is occupied entirely by the sky, whose leaden color announces the arrival of a great storm. This canvas would be followed from 1855 by numerous variations, such as the Landscape near Maisières and the Landscape of Ornans, where the coexistence of dominant rocks and vegetation remains, and in paintings Courbet made away from Ornans, in the last years of his existence, such as the Valley of the Loue, near Ornans and The Apple Trees of Pa Courbet in Ornans, the latter of which is characterized by the presence in the foreground of several apple trees with lush foliage dotted with greenish-yellow patches and a sky that is not completely clear, but with grayish clouds coming in.

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Wounded Man (1844-1854; oil on canvas, 81.5 x 97.5 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Landscape near Maisières (1865; oil on canvas, 50 x 65 cm; Munich, Neue Pinakothek) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Landscape at Ornans (1855-1860; oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm; Vienna, Gemäldegalerie der Akademie der bildenden Künste) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Valley of the Loue under a Stormy Sky (c. 1849; oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm; Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Valley of the Loue near Ornans (1872; oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm; Bristol, Bristol Museums & Art Gallery) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Papa Courbet’s Apple Trees at Ornans (1873; oil on canvas, 45 x 54.5 cm; Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen) |

As mentioned earlier, landscape for Courbet is not an element that takes a back seat, as it was in academic painting, but is deeply linked to the eventual figures of men and animals: the one was considered by him to complement the others. This can be clearly seen in some of the works in the exhibition, such as Roe Deer at the Spring, where two roe deer are joyfully bathing in the flowing water between a landscape once again consisting of rocks and trees and another roe deer in the foreground, gazing at the viewer with a lively eye; the friendly animal is still in the shade of the tree canopies, but is ready to dive with its other fellows into the cool water. Or this can be seen in two very striking paintings in which water and human figure interact within the verdant landscape: these are The Spring or Bather at the Spring and Young Bather. In the first one shows a shapely female figure, naked, back to back and with her hair up, leaning on a rock. The sensuous young woman is holding on to the leafy branches of a tree with one hand, while she is running on her other open hand upward the water flowing down from the spring; her feet are immersed in the transparent water. In the second painting, on the other hand, we see a naked, full-figured young woman who very sensually is dipping the tip of one foot into the stream of water flowing through the forest. She is also holding onto the branch of a tree with one hand, while touching her hair with the other hand. Also noticeable in this one is an absorbed, contemplative expression. Courbet, in these two paintings, addresses the theme of the nude immersed in nature: however, he does not load it with the mythological references of tradition, but rather becomes a representation of sensual pleasure in contact with the natural elements. The female mysteries are thus associated by the artist with the mysteries of nature, relative to the originating character of both.

Two young maidens, portrayed together, are the protagonists of another major work, entitled Maidens on the Banks of the Seine. This one was harshly criticized in 1857 at the Salon because of its monumental size, generally typical of historical, biblical and mythological depictions, and the sensuality that flows from the two female figures. A painting described as ugly and vulgar, according to Théophile Gautier, who described it as follows, “Two large figures, to whom one pays a compliment if one calls them easy women, lie on the grass [...] in clothes of the worst taste and seem to be disposing in a state of drowsiness of the vinasse with which the fritters are washed down in the dive bars of Asniéres.” Courbet portrayed in this huge painting (measuring 174 by 206 centimeters) two maidens lying on the grass on the bank of the Seine during a summer day. One, absorbed in her thoughts, holds her head with her hand and in her other hand clutches a large bouquet of flowers; the other girl is completely lying prone, staring with half-closed eyes at the viewer. The clothes they wear reveal that both do not belong to good society: the first wears a red dress, black lace gloves with a red beaded bracelet and a wide hat on her head; the second is in a petticoat and corset. The two girls have been interpreted by many critics as prostitutes or have thought of a homosexual connection, but Courbet seems to have been inspired by a novel by George Sand, Lélia, in which two sisters question love and sensuality. Beyond that, the artist here depicted the outdoor amusements of the new industrial society, anticipating a theme very dear to the Impressionists. The painting was executed in Paris, where the painter had moved in late 1839, and thus had the opportunity to come into contact with Parisian society, markedly different from the provincial reality from which he came.

|

| Gustave Courbet, Roe Deer at the Spring (1868; oil on canvas, 97.5 x 129.8 cm; Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Bather at the Spring (1868; oil on canvas, 128 x 97 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Young Bather (1866; oil on canvas, 130.2 x 97.2 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Maidens on the Banks of the Seine (1856-1857; oil on canvas, 174 x 206 cm; Paris, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris) |

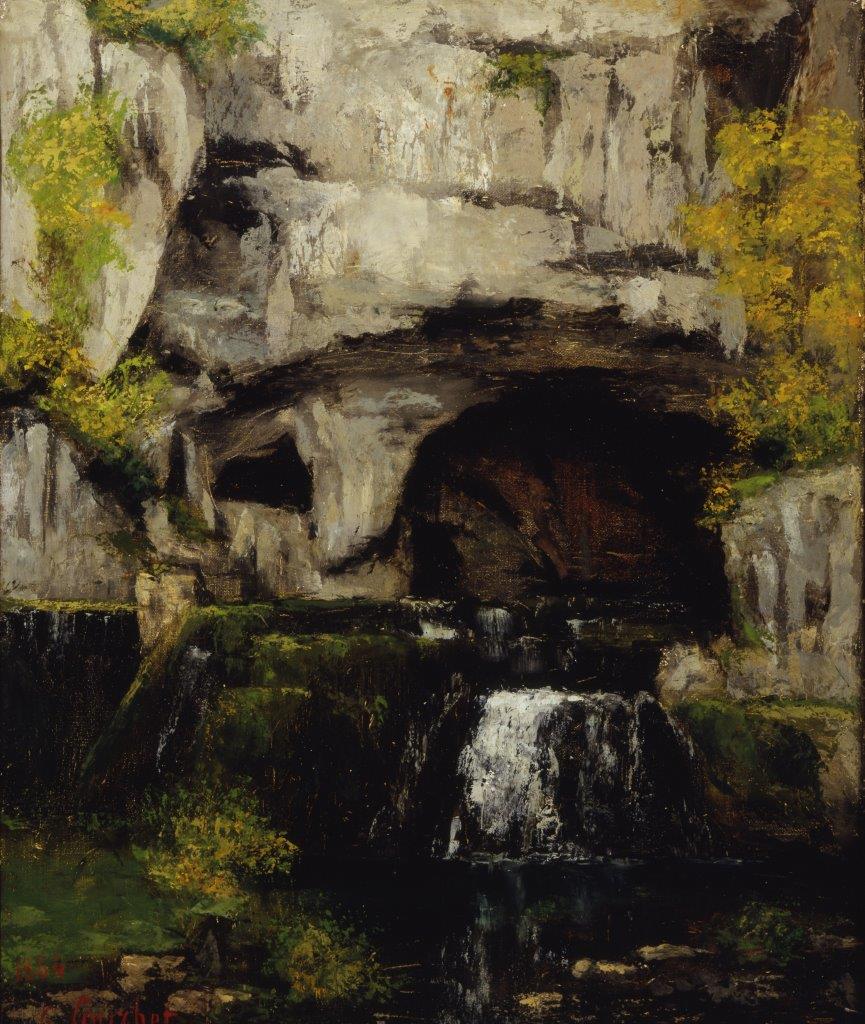

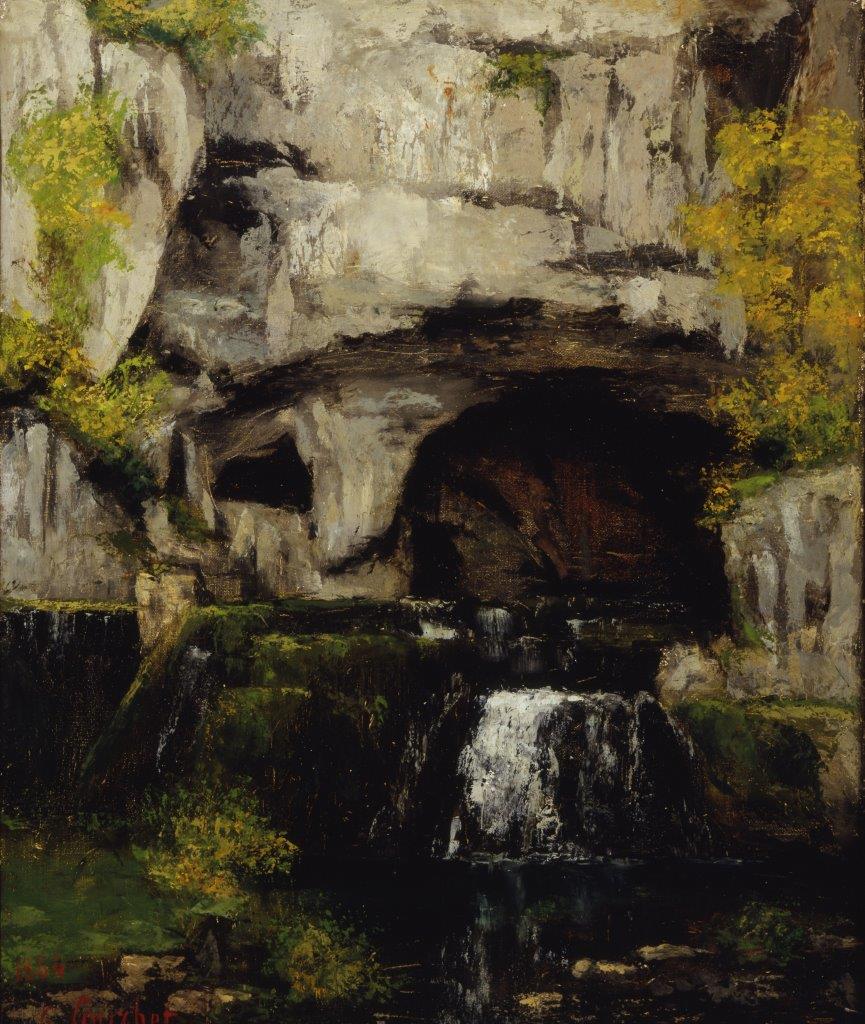

Another aspect to keep in mind is that Courbet used to paint in the open air, as evidenced by the sketchbook in the Self-Portrait exhibited in the first room: especially the landscapes were portrayed by him on site and perhaps retouched later in his studio. Examples are the two versions of the Puits noir Stream, in the Loue valley: one dating from 1855 and preserved in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the other from 1865 and housed in the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse. An entire room is devoted to the headwaters of the Loue and its tributary Lison: these works are characterized by a dark karst cavity placed in the center of the painting, from which spring water flows. A lover of nature walks and particularly in the woods of his Ornans, Courbet depicted those caves and springs that he experienced firsthand and knew very well, and he also introduces into their depiction the feeling of disquiet he experienced at the time of their discovery. Examples are the Lison Spring, The Sarrazine Cave and The Loue Spring. In the latter work he introduces at the center of the composition a small fisherman standing on a dam diverting water to a mill. The figure appears minuscule compared to the enormous dark cavity that occupies the entire painting and the majestic limestone archway, realistically rendered by Courbet using the palette knife technique: by directly spreading colors on the canvas with the palette knife, the artist was able to reproduce the material composition of the limestone.

In addition to long walks in the forests and valleys of Franche-Comté, Courbet loved to travel: travel was for the artist a reason to discover new naturalistic scenery that he could depict in his paintings. From 1854 he went for long periods to the south of France, thus coming into contact with the Mediterranean. He also stayed in Fontainebleu and spent various periods in Holland, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland. It was on the shores of the Mediterranean that in 1853 he met Alfred Bruyas, an already experienced young collector originally from Montpellier. The two immediately became friends and Bruyas was his patron. Courbet’s meeting with Bruyas would be pivotal to his artistic career and is well exemplified in the imposing painting in the exhibition The Meeting or Good Morning Mr. Courbet: the two characters overlook each other in a southern French setting; Bruyas is not alone, but is accompanied by the servant Calas and his dog. The very portrayal of each of the two main characters appears significant because it defines at first glance where they come from: Courbet carries a backpack on his shoulders, clutches a mountain stick in his right hand and a hat in his left; clothing that immediately refers to the mountain landscape. In contrast, Bruyas wears clothes of a bourgeois citizen. One could say an encounter between the mountain world and the marine world of the Mediterranean.

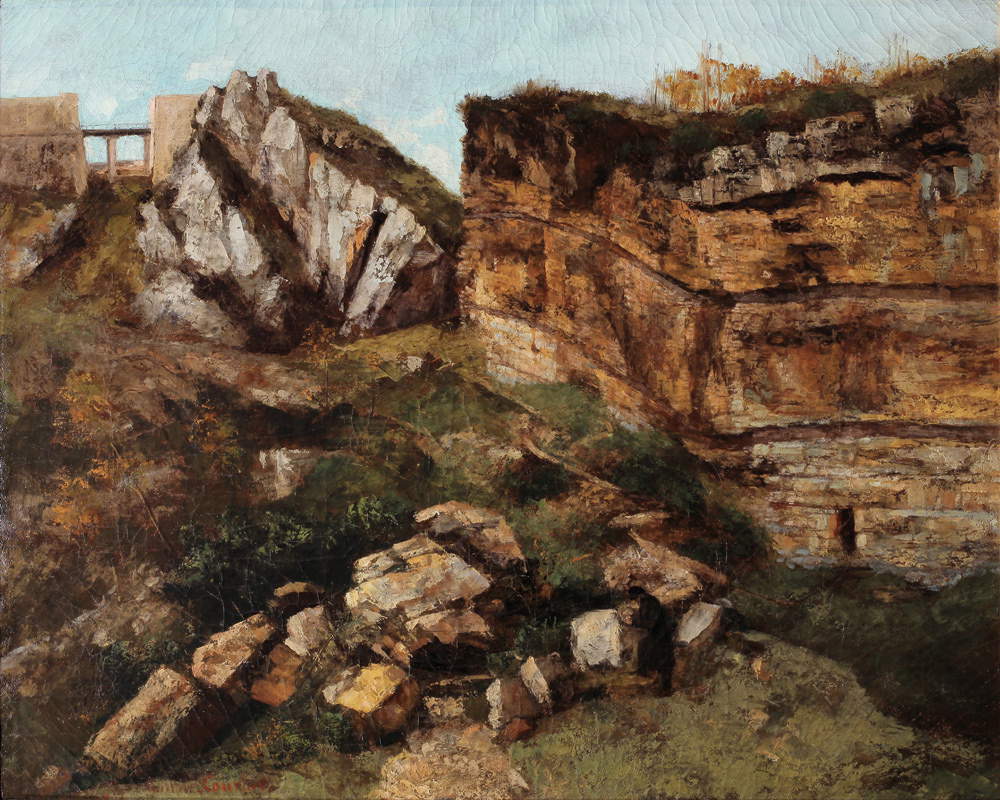

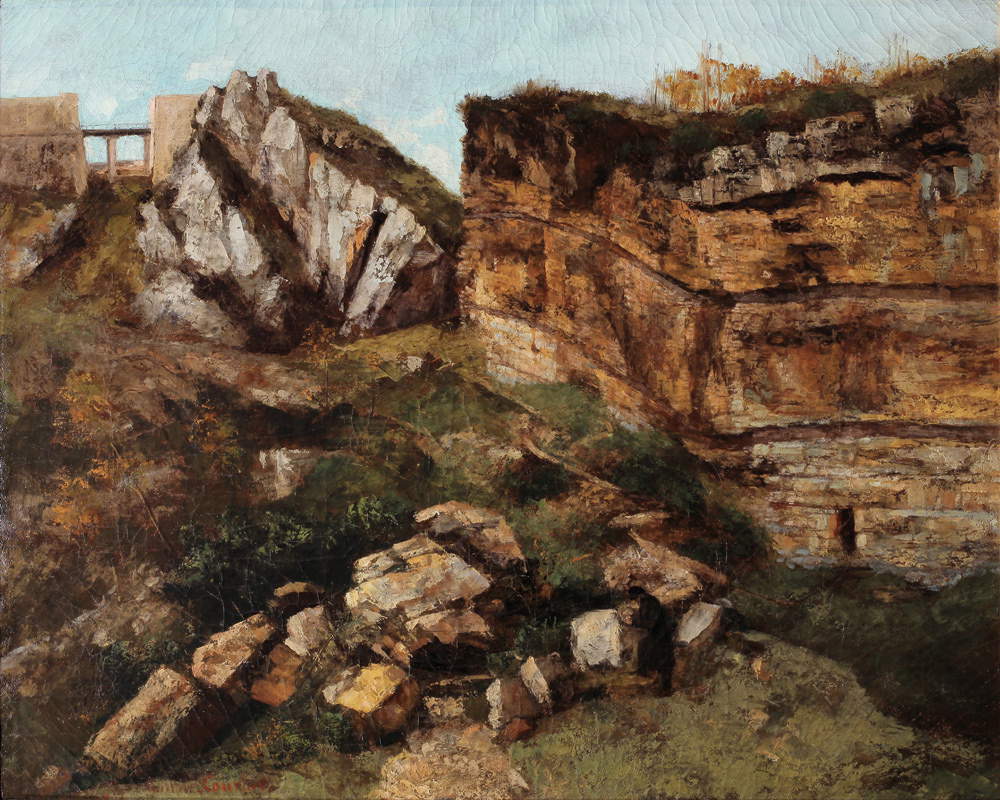

During a sojourn in Saintonge, an ancient province in the center of France, Courbet got to know Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (Paris, 1796 - 1875), whom he already knew. Corot also painted nature from life, and the interest and desire to renew landscape painting by moving closer and closer to a realistic depiction of nature, especially with regard to the subject matter of the elements, can be seen in a dialogue between two paintings made by the two artists: these are Crumbling Rock, a geological study by Courbet and Fontainebleu, an abandoned mine by Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, where in both cases it is the rock that dominates.

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Brook of the Puits noir (1855; oil on canvas, 104 x 137 cm; Washington, National Gallery) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Brook of the Puits noir (1865; oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm; Toulouse, Musée des Augustins) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Spring of the Lison (1864; oil on canvas, 54 x 45 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Sarrazine Cave (1864; oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm; Lons-le-Saunier, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Source of the Loue (1864; oil on canvas, 98.4 x 130.4 cm; Washington, National Gallery) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Meeting or Good Morning Mr. Courbet (1854; oil on canvas, 132.4 x 151 cm; Montpellier, Musée Fabre) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Crumbling Rock, Geological Study (1864; oil on canvas, 59.7 x 73 cm; Salins-les-Bains, Grande Saline) |

|

| Jean-Baptiste Camile Corot, Fontainebleu, abandoned mine (1850; oil on paper pasted on canvas, 29 x 43 cm; The Hague, De Mesdag Collectie) |

However, two entire rooms of the exhibition are devoted to seascapes. These can be divided into two series: waves and seascapes. Both are executed in the period between 1865 and 1869, when the artist was staying for long periods in Normandy, in northern France, in places that were painted very often by the next generation of artists, the Impressionists: the landscape then of Le Havre, Étretat, and other surrounding towns. The ocean has inherent a stronger and more decisive character than the sea: the frequent storms, sometimes violent, are characterized by large, foamy waves and the overhanging sky that abruptly changes color, becoming darker as the storm approaches. All these elements feature prominently in the Waves series: among the most striking examples on display is theWave housed in the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh. A large swell rising burstingly toward the sky, which is becoming darker, is in the very foreground, allowing the viewer to see distinctly each small brushstroke, accomplished with color imprinted directly on the canvas in the Impressionist manner, that constitutes the overwhelming white froth. Alongside the different variations on the theme, we note a work in which Courbet modifies the composition by adding a fishing boat in the foreground on the shore. The painting, executed in 1870, is kept in Orléans, in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, and is similar to the 1869Wave of Le Havre, where there are two boats and the tones are much darker.

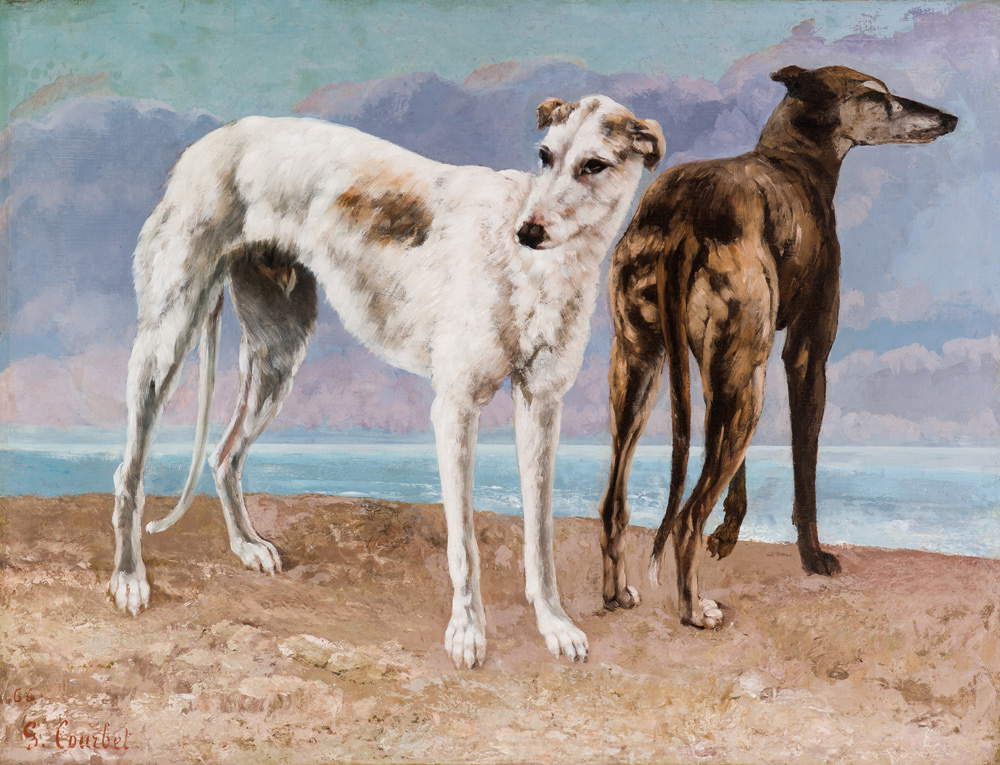

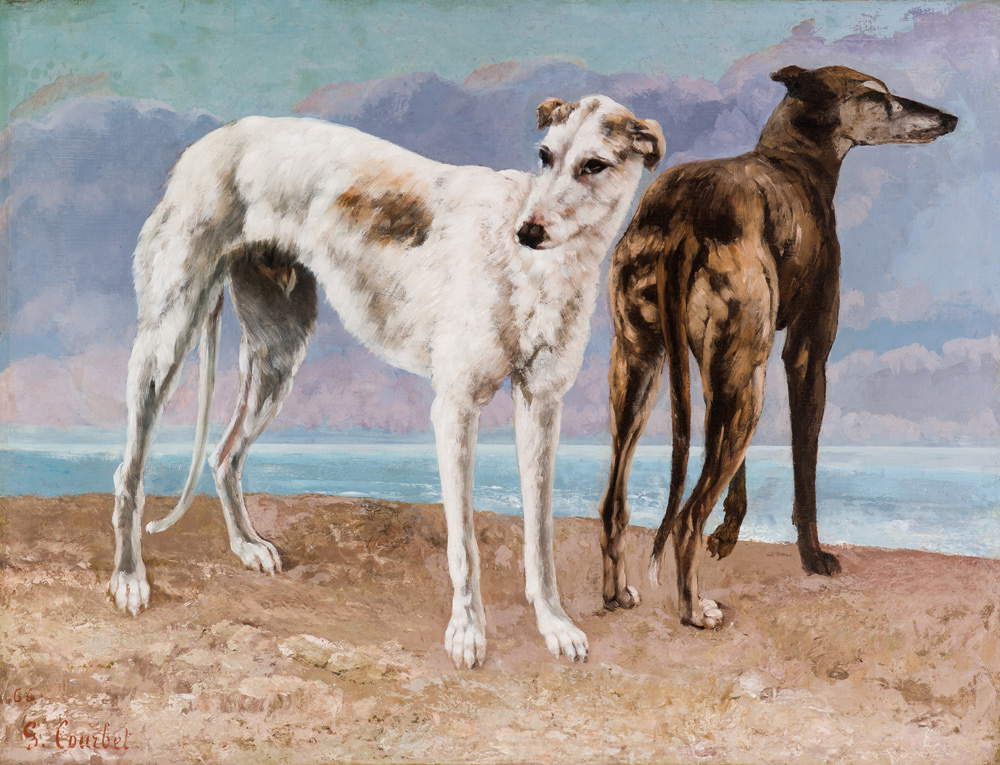

Peaceful moments when the sea is calm, on the other hand, inspired the Marine series. Attracting a close look is the splendid painting Sunset: beach at Trouville. Rich brushstrokes make the sea sparkle under a sky that is gently blushing; in the distance a small sail. Particular and unique in Courbet’s production is the painting entitled The Greyhounds of the Count of Choiseul: the work was created by the artist in the summer of 1866 in Deauville and here depicts the two beautiful greyhounds of the count by whom he was a guest; the two animals in the very foreground, depicted from a perspective at their height, have well-defined lines that stand out against the background consisting of sea and sky, elements clearly separated by a wide horizon.

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Wave (c. 1869; oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm; Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Wave (1869; oil on canvas, 71.5 x 116.8 cm; Le Havre, Musée d’art moderne André Malraux) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Sunset: beach at Trouville (c. 1866; oil on canvas, 71.5 x 102.3 cm; Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Greyhounds of the Count of Choiseul (1866; oil on canvas, 89.5 x 116.5 cm; Saint Louis, Saint Louis Art Museum) |

The last years of his life and artistic activity were marked by a nostalgic and almost romantic feeling toward his native places: in 1873 Courbet was forced to chooseexile, and thus never to return to his lands, in order to avoid prison one more time. Moving closer to socialist and anarchist ideas following his perennial rancor against imperialism and Napoleon III, he was elected to the Council of the Commune, the government that self-governed Paris from March to May 1871. For this fact and for his speech in which he had declared himself in favor of the destruction of theVendôme Column, the monument in tribute to the military victories of Napoleon I, which was actually destroyed in 1872, the artist is arrested and sentenced first to six months’ imprisonment, then to two years, with the addition of confiscation of property. He therefore moved permanently to La Tour-de-Peilz, on Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Here he painted views of Lake Geneva and Chillon Castle and glimpses of the Alps. These are landscapes with cloudy skies or red for sunset that accentuate the artist’s vision of melancholy feelings and interiority.

Remembering the Marines painted during his stays in Normandy, he produced several works on Lake Geneva, in particular light situations: at dusk, at sunset and under a cloudy sky. Wonderfully evocative is the Panorama of the Alps: the majesty of the snow-capped peaks and the remarkable skill in the depiction of rocky matter recall the mountain landscapes he painted in Franche-Comté.

The last room of the exhibition is entirely devoted to hunting, continuing in the vein of the interpenetration in the same painting of landscape, animals, and sometimes humans. Courbet had practiced in his Ornans the art of hunting, which he was very passionate about, and he reproduces this theme on canvas with the intention of a dual fidelity to the realism he professed, as an experienced hunter, and to the great pictorial tradition of the Flemish masters of the seventeenth century or contemporary English artists. Of monumental dimensions (220 by 275 centimeters) is the most dramatically charged painting in the room: the Deer in the Water. Launching a cry toward the sky, the deer leaps into the river, heading for certain death; the dramatic scene is accentuated by the surrounding landscape that appears vast but desolate and by a sky that from the color of the clouds is heralding a storm. A similar expression, with gaping mouth, is found in the deer on the ground now killed in the painting The German Hunter.

Dealt with masterfully is the theme of hunting in the snow, where hunters are sometimes men, accompanied by their faithful animals, or the animals themselves who, following the laws of nature, obtain food. Examples are, respectively, the Hunter on Horseback while Tracking and the Fox in the Snow. The former depicts a man all bundled up for the cold, but with a tired and melancholy expression, probably due to a long day of hunting that however did not yield great results, and his horse. The latter has a hunched back and is trying to sniff out the footprints of wounded prey. The bloodstained footprints in the snow hint to the viewer that not far from the depicted scene there is a wounded animal, but it is not clear which one. The tones of the painting are rather dark indicating that the long day is drawing to a close and that the clouds in the sky are approaching; even the snow does not appear white, but of a color tending toward gray. This painting is influenced by the hunting experiences of Courbet himself, a passionate hunter who spent the autumn in his Ornans so as not to miss the hunting season, and used to practice it without dogs.

The second painting mentioned above, on the other hand, depicts a beautiful fox in the foreground, all hunched over holding the tail end upward, intent on enjoying its successful hunt: in fact, with one paw it holds a mouse, its prey, and strands of the latter’s flesh sprout from its mouth.

Unlike the previous canvas, the snow is white and the landscape can certainly be described as wooded: in fact, rocks and small shrubs, also snow-covered, can be seen. On the other hand, the painting entitled The Roe Deer’s Refuge in Winter appears more scenic and tranquil: amid tall snow-covered trees forming a forest and a soft blanket of white snow covering the ground, three roe deer stand in the center of the canvas, two of which are crouched in repose and another appears to be exploring the environment in which it has taken refuge.

|

| Gustave Courbet, Lake Geneva at Dusk in Front of Bon-Port (1876; oil on canvas, 59.5 x 80 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Sunset on Lake Geneva (1874; oil on canvas, 54.5 x 65.4 cm; Vevey, Musée Jenisch) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Lake Geneva under a Cloudy Sky (1874; oil on canvas, 38 x 55.5 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Panorama of the Alps (c. 1876; oil on canvas, 64 x 140 cm; Geneva, Musées d’art et d’histoire) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Deer in the Water (1861; oil on canvas, 220 x 275 cm; Marseille, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The German Hunter (1859; oil on canvas, 119 x 177 cm; Lons-le-Saunier, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Hunter on Horseback While Tracking (1863-1864; oil on canvas, 119.4 x 95.3 cm; New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Fox in the Snow (1860; oil on canvas, 85.7 x 128 cm; Dallas, Dallas Museum of Art) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, The Shelter of Deer in Winter (1866; oil on canvas, 54.1 x 72.8 cm; Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

This concludes an exhibition itinerary, well argued with didactic apparatuses, that aims to present a theme little known to the general public and little addressed in exhibitions devoted to artists whose art is nevertheless imbued with the relationship with nature, as in the case of Gustave Courbet. The visitor, having reached the end of the retrospective, will have understood how for the artist his homeland was fundamental throughout his career and how deep down the artist’s character is sensitive. Courbet and Nature thus turns out to be a well-understood exhibition, carefully curated and arranged to allow everyone to delve into a very significant aspect of the French artist.

Accompanying the exhibition is a catalog with essays on the significance of landscape for Courbet, how for the artist nature represents not just a setting on which to set his characters, but how in an innovative and revolutionary way in relation to his contemporaneity he approached this theme, and on Courbet’s modern legacy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.