by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 20/01/2019

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Romanticism. In Milan, Gallerie d'Italia in Piazza Scala and Museo Poldi Pezzoli, from October 26, 2018 to March 17, 2019.

The first contribution on the role of the open window on the landscape in the Romantic era dates back to 1955: it was titled The open window and the storm-tossed boat: an essay in the iconography of Romanticism, and its author, Lorenz Eitner, pointed out that paintings featuring windows were unprecedented and could not be considered simply genre scenes. The window view is, in essence, a Romantic innovation: neither landscape painting nor interior view, but a “curious combination of both,” Eitner asserted. The result is an inescapable clash, that between the intimate dimension of what is on this side of the window, and the immensity of the space that opens beyond the threshold: a contrast sometimes enlivened by the presence of a figure facing the window, which the viewer catches from behind. Eitner wrote that the window gave substance to one of the favorite themes of Romantic literature: the desire, unattainable, to leave behind one’s world and the anxieties of one’s existence in order to welcome the infinite. Or, in other words, that yearning to which the Germans gave the name Sehnsucht, and which in 1834 would become (with the very title Sehnsucht) the subject of a lyric by Joseph von Eichendorff that could only open with the motif of the window: “Es schienen so golden die Sterne, / Am Fenster ich einsam stand / Und hörte aus weiter Ferne / Ein Posthorn im stillen Land. / Das Herz mir im Leib entbrennte, / Da hab’ ich mir heimlich gedacht: / Ach wer da mitreisen könnte / In der prächtigen Sommernacht!” (“The stars shone with golden light / And I stood alone at the window / And listened to the distant sound / Of the post horn in the still country. / My heart burned in my body / And I secretly thought, / Ah, if only I could travel there too / On this magnificent summer night!”).

And with a window, an early masterpiece with which Caspar David Friedrich (Greifswald, 1774 - Dresden, 1840) captured the Elbe landscape in Dresden from inside his studio, the exhibition Romanticism also opens: until March 16, 2019, for the occasion, about two hundred works are gathered in Milan, in the double location of the Gallerie d’Italia in Piazza Scala and the Poldi Pezzoli Museum, which compose an unprecedented and complete fresco of the entire vicissitude of Italian Romanticism, analyzed by themes, considered according to the evolutions it experienced in the various centers of the peninsula, and sometimes placed in a perspective of relationship with what was happening at the European level. And it could not be otherwise, since one of the declared objectives of the curator, Fernando Mazzocca, is also to establish whether the art that was produced in Italy in this broad section of the nineteenth century (broadly speaking from the beginning of the century, especially if we also consider the contribution of the so-called “protoromantics,” up to the Unification) was on a par with what emerged in the England of Turner and Constable, in the France of Delacroix and Géricault, or in the Germany of Friedrich and Runge. And again, the Milan exhibition aims to show how Italy had managed to innovate traditional models and sustain the comparison with its past: a meritorious operation, especially if we consider that even today there is a certain tendency to underestimate the Italian art of Romanticism compared to that of the immediately preceding eras.

Certainly, it was far from easy for the Romantics to assert themselves, and emblematic in this sense is the diatribe (amply evoked in the exhibition catalog) that arose around the realization of the monument to Andrea Appiani, one of the greatest neoclassical painters in Italy and elsewhere, who had died in 1817: on the one hand, artists and intellectuals upholding the tradition (we could name, among others, Vincenzo Monti and Luigi Cagnola) intended to entrust the commission to the great Dane Bertel Thorvaldsen, who would sculpt a solemn neoclassical monument, where Appiani, the “painter of the Graces,” would appear portrayed in profile in a medallion, at the center of an aedicule decorated with a relief depicting “the three Graces in a sad weeping act” (so the commission in charge of the operations had written in a letter to Thorvaldsen dated April 10, 1819). The Romantic faction, on the contrary, pushed for Appiani to be depicted in modern dress, seated, and holding (the only concession to tradition) a drawing of the Graces. The Romantics, in other words, wanted the monument to Appiani to make a total break with the past, taking into account the fact that, in the Italy of the time, a monument depicting the effigy in contemporary dress was simply unthinkable: thus a long dispute ensued that ended with the victory of the Classicists, and the monument to Appiani (which found its place in Brera), finished in 1826, appears to us today in the form in which the Classic “party” had imagined it. It was, however, the last resistance, the extreme (and ephemeral) affirmation of tendencies that soon would inexorably give way to the spread of a totally new taste and radical ruptures with respect to what had been.

|

| Caspar David Friedrich, View from the artist’s studio, left window (1805-1806; graphite and sepia on paper, 314 × 235 mm; Vienna, Belvedere) |

|

| Romanticism in Milan exhibition, hall at the Gallerie d’Italia |

|

| Romanticism exhibition in Milan, hall at the Gallerie d’Italia |

|

| Romanticism exhibition in Milan, hall at the Gallerie d’Italia |

|

| Romanticism exhibition in Milan, hall at the Poldi Pezzoli Museum |

The Romantic revolution, however, had not begun with monumental sculpture. The first signs of the new taste were felt in landscape painting, and the exhibition in Milan, after an introduction dedicated to the theme of the window, begins with a long examination of the subject, which occupies eight of the sixteen sections of which the first part of the exhibition is composed, at the Gallerie d’Italia. The opening is entrusted to the painters of the sublime, that feeling that Kant, in the Critique of Judgment, defined as a pleasure induced indirectly “by the sensation of a momentary inhibition of vital forces followed immediately by their stronger outpouring”: the sublime is, in other words, everything that is boundless and beyond human reach, that terrifies but at the same time attracts, that disquiets but at the same time fascinates. A similar feeling can be felt in the productions of some Piedmontese painters active in the early nineteenth century: a new landscape painting spread in the Kingdom of Sardinia towards the last decade of the eighteenth century, when, Virginia Bertone and Monica Tomiato write in their catalog essay, “in the tradition of topographical and descriptive vedutismo, governed by precise optical-perspective laws and by a need for documentary objectivity, a growing interest in the rendering of the values of light and atmosphere crept in, and the painters’ gaze began to fixate on the more transitory and unstable aspects of nature.” A new sensitivity to the more unusual aspects of nature was born, and evidence of this is the unprecedented attention given to the Alps, which with their crags, gorges, bridges suspended over ravines, intricate forests on the mountain shores, impervious pass routes, and the extreme weather events that often beat them, became the subject of many views capable of shaping this sentiment. Paintings such as Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti ’s (Turin, 1764 - 1831) Ascent to Moncenisio, an extraordinary landscape painter endowed with formidable topographical skills but also capable of panoramas capable of moving the soul, or Giovanni Battista De Gubernatis ’ (Turin, 1774 - 1837) Landscape in a Storm, reveal a poetic vision of nature, allow reflections on that “beau pictoresque” that had been the subject of a lecture that De Gubernatis himself gave in 1803 at the Académie subalpine d’histoire et des beaux-arts in Turin, and open the field to a totally new way of conceiving the view. However, one cannot yet speak of accomplished Romanticism, since it was these same protoromantics, on certain occasions, who opposed Romanticism: Mazzocca recalls how Bagetti, in one of his writings of 1827, had stated that “to consign all the inspiration of the arts to genius alone, to imagination, to inspiration, is too uncertain and rough a thing.” This, however, did not prevent him, says the curator, “from bending the objectivity of his vision to an emotion that ends up giving his watercolors a visionary, dreamlike dimension that seems to contradict these anti-Romantic convictions of his.” This spirit, however, was fully grasped by the artists of the following generations: significant is the work of Giuseppe Canella (Verona, 1788 - Florence, 1847) who, having updated himself on the results of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s intimate landscapes, was able to create moving scenes such as Veduta della campagna romana con temporale, a work that, through the effects of light and the evocation of particularly evocative atmospheric conditions, is capable of cloaking the landscape with an almost elegiac aura.

The scenery changes in the fifth section, devoted to nocturnal views: a motif of strong fascination for many artists, the night, from Friedrich onward (but one could make the same argument for literature: think of Leopardi’s compositions), touches the souls deep inside, and can do so both positively (the sweetness of the night is evoked, the comfort it brings to the hearts of lovers, the pleasure it arouses at the end of hot summer days, the beauty of moonlight that illuminates the waters of a placid sea) and negatively (the darkness that brings anguish and anxiety, the darkness in which witches and spirits are invoked). Exemplifying the two souls of the night are Salvatore Fergola ’s Notturno a Capri (Naples, 1799 - 1874), a quiet view of the sea of Capri’s Marina piccola illuminated by the gentle moonlight and with boats moored a short distance from the rocks, and Bagetti’s Il noce di Benevento, a terrible gathering of witches and spectres inspired by Salvatore Viganò’s dance of the same name in which the protagonist, as in the painting, is the infamous tree around which, according to local tradition, witches’ sabbaths have been celebrated since ancient times (one of which is punctually described in the Piedmontese painter’s work). An important innovation of Italian Romanticism was then the historiated landscape, that is, views in which historical events take place: main exponent of the genre was Massimo d’Azeglio (Turin, 1798 - 1866), who is credited with having first invented this singular contamination between veduta and history painting, which touches one of its peaks in The Death of Count Josselin de Montmorency (a French condottiere who fell during the Third Crusade, in 1191, to save, according to tradition, the sister of Richard the Lionheart), a work with which the artist enjoyed widespread success at the Brera exhibition of 1831 and in which the historical episode takes place in a lush exotic setting that makes the happening “almost incidental” “compared to the exhilarating description of the variety of landscape and vegetation” (Bertone and Tomiato).

Massimo d’Azeglio’s contribution turned out to be fundamental for the elaboration of a new landscape painting, but it was not the only one: the great weight that the exhibition of the Gallerie d’Italia dedicates to views is also due to the fact that some of the most disruptive renewals took place in this very sphere. These include the introduction of urban views, to which the seventh section of the exhibition is entirely devoted and whose initiator was the Piedmontese Giovanni Migliara (Alessandria, 1785 - Milan, 1837), who positioned himself as the heir of eighteenth-century Venetian vedutismo, but shifted his attention to metropolitan views and architectural interiors (his Veduta d’interno dell’Abbazia di Altacomba (Interior View of the Abbey of Altacomba ) is a lofty example), and who was soon followed by Angelo Inganni (Brescia, 1807 - Gussago, 1880), an excellent interpreter of animated fragments of the daily life of a Milan in ferment: his Veduta di Milano (which, moreover, is a work owned by the Gallerie d’Italia: the museum in Piazza Scala contains a rich collection of urban views of Milan in the early 19th century) was even described as “prodigious” by contemporary critics and transports us there, in front of the cathedral, as if we concerning could be part of the scene. From Milan we arrive in Campania, on the outskirts of Naples, where the painters of the Posillipo school (an expression initially used by critics in a derogatory way, since these artists placed themselves well outside academic circles), spurred on by the frequent requests of foreign travelers who wanted to take home a landscape as a souvenir of their stay in southern Italy, took to studying the real en plein air, producing works aimed at capturing all the mildness of the Mediterranean climate and the fullness of the southern light. The initiator of the “school” was the Dutchman Anton Sminck van Pitloo (Arnhem, 1790 - Naples, 1837), who was the first to break with the tradition of the Academy, which wanted the landscape depicted according to precise aesthetic canons, and began instead to travel with canvas and brushes to the site, to capture with color the variation of light on nature and the city: in the exhibition we see one of his Spiaggia di Chiaia da Mergellina where “the particular atmosphere of the clear and clear sunny day, fully illuminating the city, makes the perspective rigor and the intention of the eighteenth-century topographic view vanish, translating it into a real landscape, where the commoners and fishermen in the foreground, realized with quick chromatic touches, animate a real scene, of lively picturesque skill” (Luisa Martorelli). The main heir of van Pitloo is considered Giacinto Gigante (Naples, 1806 - 1876): his Naples seen from the Conocchia combines the careful investigation of reality with the strongly sentimental interpretation of the view, typical features of the Posillipo school. The “journey” in landscape painting concludes with the ninth section, dedicated to the continuers of the Venetian veduta tradition: the main one was Ippolito Caffi, who reread the production of painters such as Canaletto or Bernardo Bellotto focusing on atmospheric and light effects (almost surreal isEclipse of the Sun at the Fondamenta Nuove, from a private collection).

|

| Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti, Ascent of Moncenisio (ca. 1809; watercolor on paper, 415 × 550 mm; Turin, private collection, formerly Antonicelli collection) |

|

| Giovanni Battista De Gubernatis, Landscape in the Blizzard with Castle with Four Towers and Large Three-mullioned Window Above the Portal (1803; pencil and watercolor on white virgin paper, 457 × 585 mm; Turin, GAM - Galleria Civica dArte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Giuseppe Canella, View of the Roman Countryside with Storm (1841; oil on canvas, 122 × 170 cm; Milan, Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, on deposit at Camera dei Deputati, Rome) |

|

| Salvatore Fergola, Nocturne a Capri (1848; oil on canvas, 106 × 131 cm; Naples, Polo Museale della Campania, on deposit at Certosa and Museo di San Martino) |

|

| Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti, The Benevento Walnut Tree (Sabbath of the Witches) (1822-1826; watercolor on paper, 380 × 430 mm; Private collection - Courtesy Benappi) |

|

| Massimo d’Azeglio, The Death of Count Josselin de Montmorency near Ptolemais in Palestine (1825; oil on canvas, 149 × 202.4 cm; Turin, GAM - Galleria Civica dArte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Giovanni Migliara, View of the Interior of Altacomba Abbey (1833; oil on canvas, 56 × 72 cm; Milan, Gallerie d’Italia di Piazza Scala) |

|

| Angelo Inganni, View of the Piazza del Duomo with the Coperto dei Figini (1838; oil on canvas, 173 × 133 cm; Milan, Palazzo Morando - Costume Moda Immagine) |

|

| Anton Sminck van Pitloo, The Chiaia Beach from Mergellina (1829; oil on canvas, 53.5 × 76 cm; Naples, private collection) |

|

| Giacinto Gigante, Napoli vista dalla Conocchia (1844; oil on canvas, 53 × 79 cm; private collection) |

|

| Ippolito Caffi, Eclisse di sole alle Fondamenta Nuove (1842; oil on canvas, 88 × 152 cm; Private collection) |

After an interlude devoted to the theme of I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed ), which inspired many artists of the time, the exhibition moves on to examine the Romantic portrait, an area in which a sort of rivalry between Giuseppe Molteni (Affori, 1800 - Milan, 1867) and Francesco Hayez (Venice, 1791 - Milan, 1882) was consummated: the former was the author of elegant, disengaged and mundane portraits istoriati (i.e., set in spaces that were rendered with admirable descriptive minutiae: it was Molteni himself who invented this genre), whose exuberance pushed almost to the point of ostentation placed them in an almost direct line with the great Baroque portraiture, while the second followed Molteni on his “terrain” but, unlike his colleague, the Venetian focused on apsychological introspection that often went so far as to involve even the surrounding landscape, seen almost as an extension of the subject and not as a mere setting for the portrait. The exhibition allows us to advance a comparison between Molteni’s superb Portrait of Antonio Visconti Aimi, which depicts the proud young marquis inside his home, surrounded by the objects of which he was proud, and the coeval Portrait of Countess Teresa Zumali Marsili with her son Giuseppe, considered by Mazzocca to be “one of Hayez’s and the century’s most moving.” and full of sixteenth-century reminiscences (especially in the soft colorism and elongated forms) and symbolic meanings (the pose similar to that of a Madonna and Child, probably motivated by the fact that the child depicted died as a child, but we do not know whether the work was executed before or after the tragic event) that give us an image of rare intensity, almost solemn.

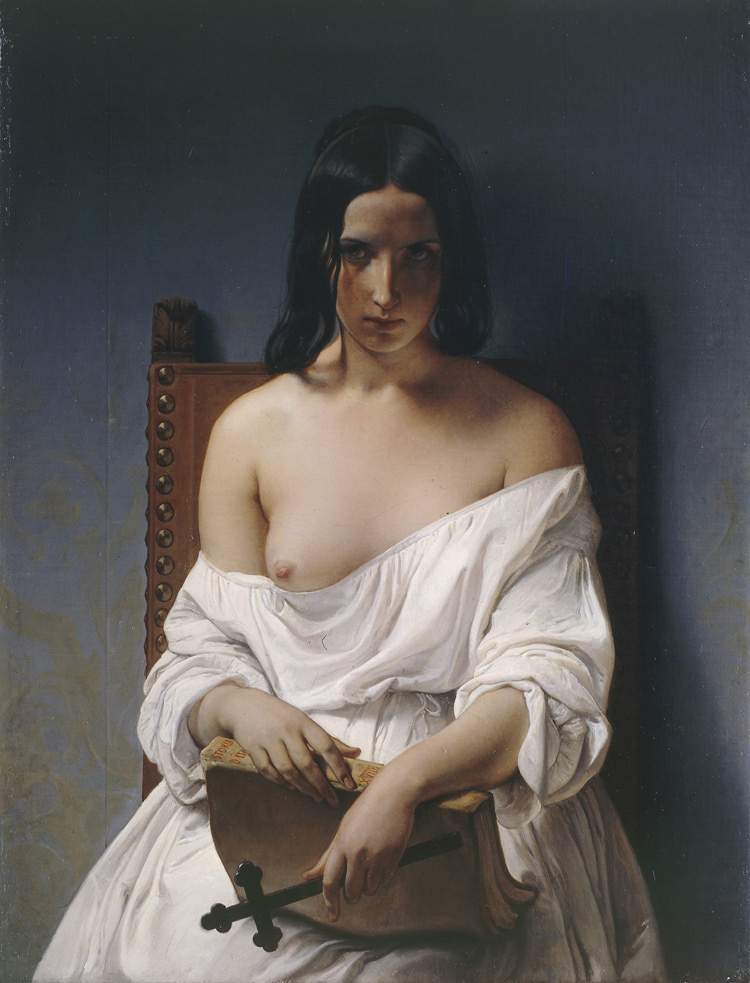

Sacred and profane meet in the next two sections, the twelfth and thirteenth: the first is devoted to the nude, the second to Romantic religiosity, and they occupy the same room. Certainly not by chance: note, for example, the languid Bride of the Sacred Songs, a work by Gaetano Motelli (Milan, 1805 - Besana Brianza, 1858) inspired by the figure of Sulamite (the bride who appears in the Song of Songs) and which aroused great attention in Milan when it was exhibited, precisely because of that softness and sweetly dreamy air that might have seemed excessive, or at least ambiguous, for a religious subject. In any case, if one thinks of nude images in the Romantic era, it is impossible not to mention the provocative heroines of Hayez, who was also one of the most sensual painters in all of art history. Right on time, the Milanese exhibition brings to Piazza Scala the celebrated Meditation, a work in which the nudity of the beautiful young woman depicted is motivated by allegorical justifications (the uncovered breast alludes to Italy nurturing her children: the painting is dated 1851), but it is necessary to put the accent on a sensational unpublished work devoid of symbolic references and charged with a dense eroticism that reveals all of Hayez’s (passionate) love for the female gender: it is the Nudo di donna (Model at Rest), which has no other purpose than to portray, in all its intimacy, a half-naked model lying on an unmade bed. And if we are talking about the nude, we must also point out the differences between a virginal and innocent nude, which alludes to a dimension of purity and sincerity, such as the Eve tempted by the serpent by Natale Schiavoni (Chioggia, 1777 - Venice, 1858), and the carnal and lascivious nude, such as the shocking Orgy by Torquato Della Torre (Verona, 1827 - 1855), a sculpture that is difficult in terms of content and technique, and whose protagonist is a nude woman abandoning herself disheveled on a throne after intercourse. The turning point of religious painting toward a sensibility more attentive to reality is witnessed by paintings such as The Education of the Virgin by Giacomo Trécourt (Bergamo, 1812 Pavia, 1882) orEpisode of the Flood by Domenico Induno (Milan, 1815 - 1878), divided by intent (the former tries to be reassuring, the latter instead moves and is powerful), but united by the intentions of seeking a painting from which a “need for the domestic, the intimate and the natural” (Giuseppe Fusari) would transpire.

We move toward the conclusion of the itinerary in Piazza Scala first with a room devoted to the theme of the “redemption of the wretched,” with the last and the defeated who populate the transforming cities becoming the object of new and profound attention, as well as subjects worthy of being depicted in works of rare intensity (Molteni’s little working children are not to be missed), which will pave the way for realist painting in the second half of the century. Then it was the turn of the section (the penultimate of the exhibition) devoted to history painting, which was also profoundly renewed in that it was no longer devoted only to mythological subjects or those taken from ancient history, but also devoted to the representation of episodes in the history ofmodern Italy, or to current events: the artists (above all Hayez, the one who started the revolution of the genre: in the exhibition he is present with the unfailing Last Kiss between Romeo and Juliet) elaborated compositions in which the narrated dramas set out to emotionally involve the viewer, an unprecedented goal for history painting. This resulted in works dense with pathos: worth the example of Saremo liberi! (We shall be free!), a painting by Cesare Mussini (Berlin, 1804 - Florence, 1879) that recounts the extreme sacrifice of Greek patriot Georgios Rhodios, who takes the life first of his wife and then of himself so as not to fall into the hands of the Ottomans during the Greek War of Independence (a topical theme that inflamed Romantic artists). We return to the main hall of the Gallerie d’Italia in Piazza Scala and end our visit to the first part of the exhibition with the section on Romantic sculpture: sculpture that, at first glance, struggled to establish itself, since even after the Restoration the neoclassicals still held firmly in the field. However, first the purist sculptors, above all Lorenzo Bartolini (Savignano di Prato, 1777 Florence, 1850), who is present in the exhibition with his marvelous Fiduca in Dio (a sort of hymn to natural beauty that contrasted with the ideal beauty of the neoclassicists), and then the artists of civil commitment such as Alessandro Puttinati (Verona, 1801 - Milan, 1872) and Vincenzo Vela (Ligornetto, 1820 - 1891), the latter capable of stunning and almost violent portraits of historical figures (in the exhibition we see, respectively, Masaniello and Spartacus), opened the way to entirely new possibilities and toward what would become the sculpture of the second half of the 19th century.

|

| Giuseppe Molteni, Portrait of Antonio Visconti Aimi (1830-1835; oil on canvas, 134 × 114 cm; Marco Voena Collection) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Portrait of Countess Teresa Zumali Marsili with her son Giuseppe (1833; oil on canvas, 129 × 105 cm - Lodi, Museo Civico (on loan from ASST - Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale di Lodi) |

|

| Gaetano Motelli, The Bride of the Sacred Songs (1854; marble, 140 × 55 × 75 cm - Litta Collection) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, The Meditation (1851; oil on canvas, 92.3 × 71.5 cm; Verona, Galleria dArte Moderna Achille Forti) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Nude of a Woman (Model at Rest) (c. 1850-1860; oil on canvas, 65 × 50 cm - Private Collection) |

|

| Natale Schiavoni, Eve Tempted by the Serpent (The Earthly Paradise) (c. 1844; oil on canvas, 150 × 101 cm - Gomiero-Grasselli) |

|

| Torquato Della Torre, Lorgia (1851-1854; marble, 111 × 96 × 105.5 cm - Verona, Galleria dArte Moderna Achille Forti) |

|

| Giacomo Trécourt, Education of the Virgin (1839; oil on canvas 280 × 190 cm - Villongo, parish church of San Filastro) |

|

| Domenico Induno, An Episode of the Deluge (1844; oil on canvas, 124 × 165 cm - Banco BPM Collection) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, The Last Kiss between Romeo and Juliet (1823; oil on canvas, 291 × 201.8 cm; Tremezzo, Villa Carlotta) |

|

| Cesare Mussini, Giorgio Rhodios Killing His Wife Demetria and Then Himself to Escape Muslim Cruelty (We Shall Be Free!) (1841-1851; oil on canvas, 170 × 142 cm - Turin, Musei Reali, Palazzo Reale) |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, Trust in God (1833-1836; marble, 93 × 45 × 64 cm - Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli) |

|

| Alessandro Puttinati, Masaniello (1846; marble, 212 × 50 × 105 cm - Milan, Galleria dArte Moderna) |

|

| Vincenzo Vela, Spartacus (1850; marble, 208 × 80 × 126.5 cm; Lugano, Palazzo Civico - MASI - Museo dArte della Svizzera Italiana, Lugano. City of Lugano Collection. Deposit of the Gottfried Keller Foundation, Federal Office for Culture, Bern) |

The itinerary at the Poldi Pezzoli Museum (this is not a separate exhibition: it is a continuation of what visitors find in Piazza Scala) picks up on the thread of historical painting: the first section goes into the specifics of the lives of illustrious men of the past or of literature. These were, again, themes that, at a time when, writes Beatrice Piazza, “pressing foreign domination was stifling the spirit of the ancient primacy of the nation,” were to "stand as exempla of virtue and a reminder of the awareness of origins." Not only that: among Romantics all over Europe, the cliché of theartist-genius, passionate and tormented spread, and certain greats of yesteryear were almost given a sort of mythical aura, as happened, for example, to Torquato Tasso, who in the first decades of the 19th century experienced an explosive popularity, confirmed by the growing consideration reserved for him by artists. Two examples can be found at the Poldi Pezzoli: one is the Torquato Tasso declaiming the Gerusalemme Liberata at the Este court, by Francesco Podesti (Ancona, 1800 - Rome, 1895), a painting that echoes all the passion that the Romantics had for the poet’s production (as well as for the biographical story), while the other is The Death of Torquato Tasso by the German Franz Ludwig Catel (Berlin, 1778 - Rome, 1856), a painting that dramatizes with almost theatrical accents the departure of the great man of letters. Just as literature is present in a special section at the Gallerie d’Italia with I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed), so too is it at the Poldi Pezzoli, as one room aims to delve into the Divine Comedy and its characters: of note is the presence of The Count Ugolino in the Tower by Giuseppe Diotti (Casalmaggiore, 1779 - 1846), an artist we could almost define as “transitional” between classicist instances and new painting, and who responded to the innovations introduced by Hayez with his equally modern paintings although tinged with a gravitas not oblivious to the ties with the academy, which the Lombard painter never wanted to sever.

One of the most interesting and singular sections of the exhibition is the one that deals with theself-portrait, offered to the public in its most varied declinations: it goes from one of the paintings-symbols of the Romantic sensibility, the self-portrait of Tommaso Minardi (Faenza, 1787 - Rome, 1871), who depicts himself alone in a poor bohemian room, and through the proud self-portraits of Hayez (who throughout his career never put an end to his own penchant for self-representation, which also led him to self-portray himself in the most bizarre situations, as evidenced by his Self-portrait with a lion and a tiger: “the artist, like a beast in a cage, is in conflict with society,” Mazzocca points out) and an unpublished Natale Schiavoni portraying his son Felice in an elegant and carefree family portrait, we come to theSelf-Portrait with a Camera by Alessandro Guardassoni (Bologna, 1819 - 1888), who, by including the medium in his painting, already seems to foresee the future fate of art. We then continue with a room dedicated to the uprisings of 1848: the revolution bursts in with its load of tension but also, and perhaps above all, in all its brutality, narrated unfiltered by a painting in which an abuse of power is in progress, theEpisode of looting during the Five Days of Milan by Baldassare Verazzi (Caprezzo, 1819 - Lesa, 1886), and by one in which the violence has already been accomplished. It is the Trasteverina hit by a bomb by Gerolamo Induno (Milan, 1825 - 1890), and when faced with the touching image of the poor child, struck dead by a bomb during the defense of Rome in 1849, it is almost impossible not to give in to compassion. Romanticism ends with a sort of exhibition within the exhibition, namely the last section (the fifth at the Poldi Pezzoli), dedicated to Giambattista Gigola (Brescia, 1767 - Tremezzo, 1841), a highly refined miniaturist who, while remaining tied to neoclassical stylistic features, felt the new feeling with his elegant paintings on ivory.

|

| Francesco Podesti, The Badger at the Court of Ferrara (1831; oil on canvas, 169 x 250 cm; Ancona, Pinacoteca Civica) |

|

| Franz Ludwig Catel, The Death of Tasso (1834; oil, 129.5 x 179.5 cm; Naples, Royal Palace) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Count Ugolino in the Tower (1831; oil on canvas, 173.5 x 207.5 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

|

| Tommaso Minardi, Self-Portrait (c. 1813; oil on canvas, 37 x 33 cm; Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Self-Portrait with Lion and a Caged Tiger (1831; oil on panel, 43 x 51 cm; Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli) |

|

| Alessandro Guardassoni, Self-Portrait with Camera (1855-1860; oil on canvas, 125 x 92 x 7.5 cm; Bologna, Fondazione Gualandi a Favore dei Sordi) |

|

| Gerolamo Induno, Trasteverina struck by a bomb (1849; oil on canvas, 114.5 x 158 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale dArte Moderna) |

|

| Some of the works of Giovanni Battista Gigola in the exhibition |

There are no caesuras between the two distributions of the exhibition: both the rooms at the Gallerie d’Italia and the rooms at the Museo Poldi Pezzoli contribute to animate a single discourse, which would be difficult to imagine separate because, if the intent of the exhibition is to evaluate Italian Romanticism under all its aspects, in the first case there would be a lack of an ending, and in the other there would be a lack of presuppositions (although the rooms at the Poldi Pezzoli find their common thread in the examination of the contribution that Romantic art made to the elaboration of the ideals that later gave rise to the Risorgimento). A discourse that, moreover, could extend well beyond the boundaries traced by the title, since examining the totality of the Italian Romantic movement means talking about several “romanticisms,” and here it would be necessary to think, just by way of example, of the case of sculpture, of the clear gap that exists between a Pietro Tenerani and a Vincenzo Vela, of the detachment from the themes of tradition that was much slower in sculpture than in painting: the exhibition focuses on a small number of works, but all of exceptional importance. The all-encompassing approach of Romanticism is also confirmed by the constant references to the history and literature of the time, which are then punctually reflected (as well as, of course, in the rooms in which the references are made explicit) in the catalog, an excellent tool for study also because the exhibition presents as many as thirty unpublished works (and two of these are also given in this contribution), a sign that much remains to be studied on Italian Romanticism.

As recalled at the outset, the exhibition’s thesis is to sustain the validity of Italian Romanticism, both in relation to what preceded it and in the face of what was emerging in Europe at the time. In order to provide the audience with stringent terms of comparison, the exhibition also does not fail to display works by Friedrich, Corot, Turner and other international protagonists of the time, although the viewpoint is not one of comparative development: the gaze remains mostly focused on Italy, and Romanticism is analyzed especially in its internal dynamics and in the meanings it knew in the various regions of Italy (although, as one might expect, it is especially on Milan that the exhibition dwells, since the Lombard capital was undoubtedly the main driving force behind Romanticism in the peninsula, so much so that it was defined by Mazzocca as “the cultural capital of an Italy that politically did not yet exist”). The result, therefore, is a reading that does not fail to intertwine with the political events of Italy at the time, with painting and sculpture seen as the protagonists, along with letters and music, of that season in which through art, too, Italy gained self-awareness and, in the end, achieved its unity. The result, for what is the first exhibition on Italian Romanticism seen as a whole (and which therefore in some cases consolidates and in other cases reconsiders the critical positioning of the artists who are its protagonists: for d’Azeglio and Molteni, for example, very prominent roles emerge), can only be said to be fully positive, and open to future developments.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.