Hokusai in Pisa, many masterpieces and some uncertainty

The Hokusai exhibition that opened at Palazzo Blu in Pisa on Oct. 24, 2024, and will be open until Feb. 23, 2025, is now nearing its close. Once again, the patrician palace overlooking the Arno River has offered in the fall-winter period, a major exhibition, linked to a fundamental name in the history of art and of great appeal. It is part of a far-sighted exhibition strategy that has carved out for Palazzo Blu a leading role in the Italian cultural scene, bringing its exhibitions to be an unmissable event. The feedback this time as well is not slow in coming, with the organizers announcing that they have abundantly passed the barrier of over 75,000 visitors, and with a final forecast that should be around 100,000 visitors, and to reach the set goal, for all weekends in February the exhibition hours are extended until 11 pm.

By now it is not uncommon to come across exhibitions in Italy dedicated to Japanese art and Hokusai in particular, but the Pisan exhibition has the undoubted merit of having been built on masterpieces of great quality: in fact, it exhibits more than 200 works from the Edoardo Chiossone Museum of Oriental Art in Genoa and the Museum of Oriental Art in Venice, and a few others pertaining to Italian and Japanese private collections, in a project that was curated by Rossella Menegazzo, professor of East Asian art history at the University of Milan. Katsushika Hokusai ’s fame is so vast even among the general public that it has made the artist the symbol (probably unwarrantedly) of all the art of the Rising Sun, and in some ways even of Asian art. A painter and printmaker, Hokusai was born in 1760 in Edo, now Tokyo, to die there after a long and successful life in 1849. His celebrity, particularly in the West, is linked to graphic art, while in his homeland he was able to garner considerable acclaim for all his output, including his painting, which led him to distinguish himself in artistic competitions and challenges, where he was noted for an eccentric and creative character. Among the many anecdotes bordering almost on hagiography, the creation in 1804 of a portrait of Daruma, deified patriarch of Zen Buddhism, on an area of about 200 square meters of paper is often mentioned. The work, done in a kind of happening, was acclaimed by the public, just as was one of the opposite sign, in which he painted a bird in flight on a grain of rice. Also in 1804, invited to a painting competition attended by Shōgun Tokugawa Ienari, he apparently painted sinuous strokes of blue on a disassembled sliding door, then took a chicken and dipped its feet in red pigment, finally letting it paw on the painting. Once the door is put back in place, here is the Tatsuta River, over which the red maple leaves flutter, referencing an image from a famous poem.

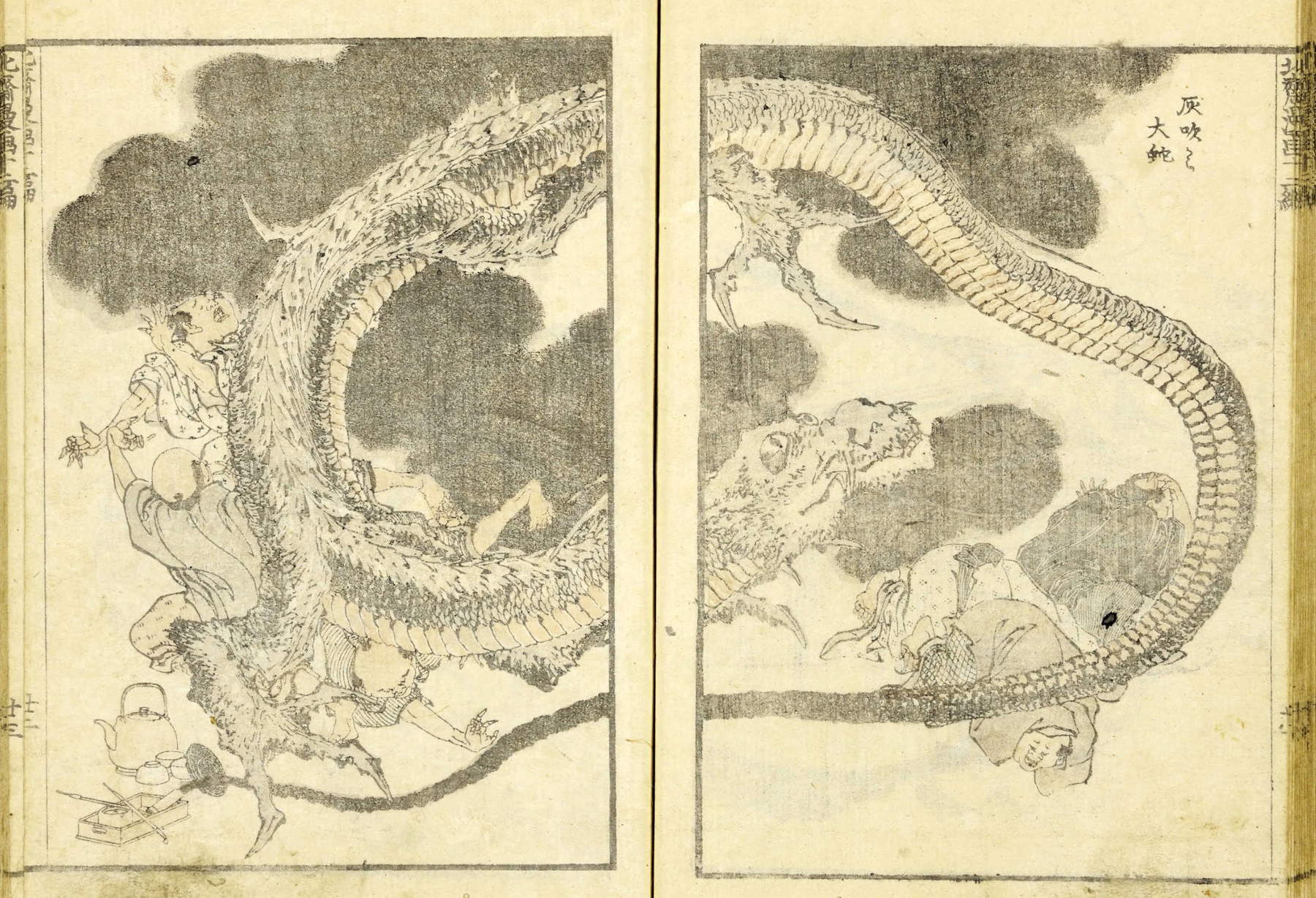

Whether these episodes are true or partly exaggerated matters little, for they restore the flair of a man who devoted his entire life to art, producing more than three thousand prints, and many paintings, of which at least a thousand have come down to us, two hundred illustrated books, and countless drawings and sketches. His work is inscribed in the Japanese school of painting ofukiyo-e (images of the floating world), a strand that developed throughout the Edo period, that is, from the seventeenth century until the end of the nineteenth. This was a period in which Japan was a sakoku country, that is, one connoted by a policy of isolation, and in which the shogunal power, at the head of a feudal organization, which had effectively ousted the emperor, had imposed as a sign of loyalty to its daimyo to reside for long periods of the year in Edo, where the shōgun lived. This led Edo, a small fortified village, to become the most populous megalopolis in the world, the scene of the constant rituals imposed by power. Gaining from this was the merchant and artisan class, which became rich by providing the services that this large apparatus needed, and concomitantly a communal culture hinged on the belief in an ephemeral life, which therefore had to be fought by escaping into pleasures: the theater, travel, pleasure houses, and the beauties of the world, such as precisely art and poetry. The ukiyo-e prints are the thermometer of this change in taste, abandoning traditional themes to embrace contemporary subjects involving restaurants, theater, tea houses, post stations, and more. These prints were generally not the preserve of the country’s most educated elite, but were designed for a massed audience. They were polychrome woodcuts, which reached a high degree of technical perfection in Japan, involving the collaboration of artists, publishers, engravers, and printers. The design provided by the artist was reproduced on wooden stencils, one for each hue or detail to be inked, up to the use of as many as twenty. Hence the misunderstanding of the West, which has long thought that this art was an expression of an aristocratic society, and not “figurines sold for two cents” as Henri Focillon attempted to demythologize.

The Pisa exhibition brings together a rich selection of the prints that bewitched the world, particularly those of famous views(meishoe) depicting Japan’s most picturesque locations, from natural ones such as mountains, waterfalls, rivers and gardens to man-made ones such as bridges, temples, shrines, restaurants and inns. They are works by Hokusai made around 1830 and pertaining to the series of Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, Unusual Views of Famous Japanese Bridges of All Provinces, and Journey Among Japanese Waterfalls.

They show compositions of high naturalism, where natural phenomena or architectural instances are sometimes the protagonists, at other times the background to a population engaged in the labors of daily living, as they go along with the relentless change of the seasons. The prints, always marked by a great narrative vivacity, alternate between those described in the minutest details and those entrusted to a few strokes and vast, soothing backgrounds, as in the print The Kintai Bridge in Suo Province. In some of these prints it is also possible to notice the use of embossing, small hollow impressions, which form animated textures that give tactile values to details, such as rippling water, fur, or scales. But the absolute star of this production is the brilliant color scheme, sometimes entrusted only to blue, other times to multiple colors.

![Katsushika Hokusai, The [Great] Wave by the Coast of Kanagawa Kanagawa oki namiura), from the series Katsushika Hokusai, The [Great] Wave by the Coast of Kanagawa Kanagawa oki namiura), from the series](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2025/2987/hokusai-la-grande-onda-di-kanagawa.jpg)

![Katsushika Hokusai, Clear Day with South Wind [Red Fuji] (Gaifu kaisei), from the series Katsushika Hokusai, Clear Day with South Wind [Red Fuji] (Gaifu kaisei), from the series](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2025/2987/hokusai-fuji-rosso.jpg)

The most iconic works belong to the series dedicated to Mount Fuji, a volcanic relief so sacred to Japanese culture that it has been given the honorific title San, which in Hokusai’s prints is generally placed in the background and barely visible, except for the print known as Red Fuji, which in the Palazzo Blu exhibition is shown in three versions that have different gradations of color and brilliance, and Thunderstorm below the summit. Hokusai’s best-known work, The Great Kanagawa Wave, also belongs to this series, although in the tangles of the sea the mountain is barely perceptible. This masterpiece of graphic marks and coloring is perhaps one of the first ukiyo-e prints in which the use of Prussian blue, discovered in Europe and imported to Japan around 1829 via Dutch ships, is fully adopted, showing how the isolation of the Japanese country was not exactly watertight. The great wave, which, like all Japanese works, should be read from right to left, has often been viewed by Europeans from a romantic perspective, as a stepmotherly nature towering over man. Hokusai wanted instead to stop an ephemeral phenomenon par excellence, and at the same time show the hard life of fishermen, who nevertheless find almost a communion with creation. The print present in Pisa bears witness to the great success it had, so much so that it was printed in thousands of copies, although evidently the earliest ones are those of better quality: the one exhibited here already shows advanced wear of the matrix found in the discontinuous stroke of the wave on the right, as well as in the seal on the left, and by a dimmer brilliance of the blue.

“The old madman for painting,” as Hokusai called himself, was also the promoter of a school with several students, and in the course of his life he produced numerous drawing manuals, including Manga, which began publication in 1814 and were concluded with the fifteenth volume, published posthumously in 1878. Also present in the exhibition in a few copies, these are splendid volumes, inexhaustible samplers of images, in which Hokusai’s passion and curiosity for every kind of form, object, animal or man is evident. These were the first illustrations with which Europeans became acquainted with Japanese art: it is said that Mangas were used as wrapping paper for porcelain and were thus discovered by French artists.

A small section also exhibits the artist’s efforts in the genre of Shunga (spring images), illustrations of an erotic nature, to which artists willingly lent themselves because they guaranteed a secure financial income. To escape censorship, the covers were laced with winking but not explicit drawings, while unrestrained sex scenes unfolded inside, where intimate attributes were exacerbated: in an attitude quite foreign to the West, these images, however unseemly, did not sin in compositional and drawing quality.

The exhibition continues with the more refined production directed to a cultured and elite audience: to this genre belong the Surimono (printed things), commissioned by private individuals for special occasions, such as year-end greeting cards, calendars or invitations. Widespread in poetic circles, they masterfully combined illustrations freer in inventiveness and calligraphy, in a marriage, that of word and art, quite common in Japan. Poetic compositions blended and complemented the images, the subjects purged themselves from the contemporary to drink in ancient iconography, drawn from tradition, mythology, and the sacred. Because they were designed for a high-ranking clientele, the colors, though more delicate, are obtained from the finest pigments, and the finest papers are often decorated with gold, silver or copper dust. Although their print runs were absolutely limited, far rarer, however, are the paintings brought to the exhibition made on rolls of silk, cloth or paper.

These works show Hokusai’s continuous efforts and self-denial in improving his style: indeed, he hoped to deepen in old age the innermost meaning of things, and to be able to infuse even a dot and a line with life of its own. Without the limitation of translating the drawing into print, his great expressive power made up of fluid outlines, as if traced by the pen of a calligrapher, is expressed here. Various are the paintings of beauties, dedicated to women or young people, which, while renouncing a precise physiognomic connotation, boast traits of great verism, as in the portrait of a woman giving birth made in 1817. Of the following year is the work Tiger among the bamboos gazing at the full moon, which, despite betraying a lack of knowledge of the animal, is denoted by a vividness reminiscent of the best works of the Dogan Rousseau or our own Ligabue. Also featured here are essays by the students who carried on his tradition, including his daughter Ōi, who frequently collaborated with her father. Also on display are some works by contemporary artists, which should testify to the influence that Hokusai’s art still has in the art of our own day, but leave the feeling that they are merely quotations in a pop key.

In conclusion, the Pisa exhibition is an almost jaw-dropping journey, thanks to the quality of masterpieces, some not often seen in the frequent exhibitions that follow one another around the peninsula. However, some weaknesses of the exhibition also remain to be pointed out. We have already made mention of the comparison with contemporaries, which cannot in any way exhaust the phenomenon of Japanism, that is, the tendency of Western artists to feed on the art of the Rising Sun in order to overcome the limits of their own culture and propose new solutions and schemes.

The exhibition evidently has no interest in proposing any research or advancement in studies: in line with Palazzo Blu’s exhibition policy, the show is intended to be a media sensation and a sure-fire success, a goal that I do not feel the least bit demonized by. For this reason, however, some choices seem poorly understandable: first and foremost, that related to the explanatory apparatuses, which forgo outlining any biographical itinerary on the artist or on the Japanese context, cultivating the risk that the visitor will leave the exhibition with eyes full of masterpieces but without any additional information on Hokusai’s extraordinary parabola in the art world.

Perhaps even more unforgivable, in my opinion, is another omission: if this exhibition was possible in Italy today, it is due to the foresight of two extraordinary figures, Edoardo Chiossone and Enrico di Borbone, who in the 19th century, first among many, made tightrope walking trips to secure these extraordinary masterpieces. In particular, Chiossone (to whom most of the works on display belonged), who was called to work in Japan at the Ministry of Finance’s Department of Valuables, stayed there for twenty-three years and died there. Because he was an artist and engraver, he sensitively collected more than three thousand woodcuts and numerous paintings and volumes of rare quality, and then destined them to Genoa, his hometown, where they formed the museum that still bears his name.

Here, the debt of gratitude to these people and their museums, should definitely have been more evident. And while perhaps too much would have been paying it in the title, even with more glossy museums it is common practice, as happened in the previous Palazzo Blu exhibition “The Avant-Garde. Masterpieces from the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” at the very least it would have been fair and nonetheless interesting to recount some of its collecting history, as indeed is done in the catalog. Perhaps someone among the thousands of visitors who flocked to the Pisan event would have been enticed to visit the Museo d’Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone in Genoa and the Museo d’Arte Orientale in Venice, which we too seldom hear about. However, on the whole, the Hokusai exhibition in Pisa is definitely an important event, which, though with some smears, is worth a visit.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.