Henri Cartier-Bresson, the decisive instant of the South

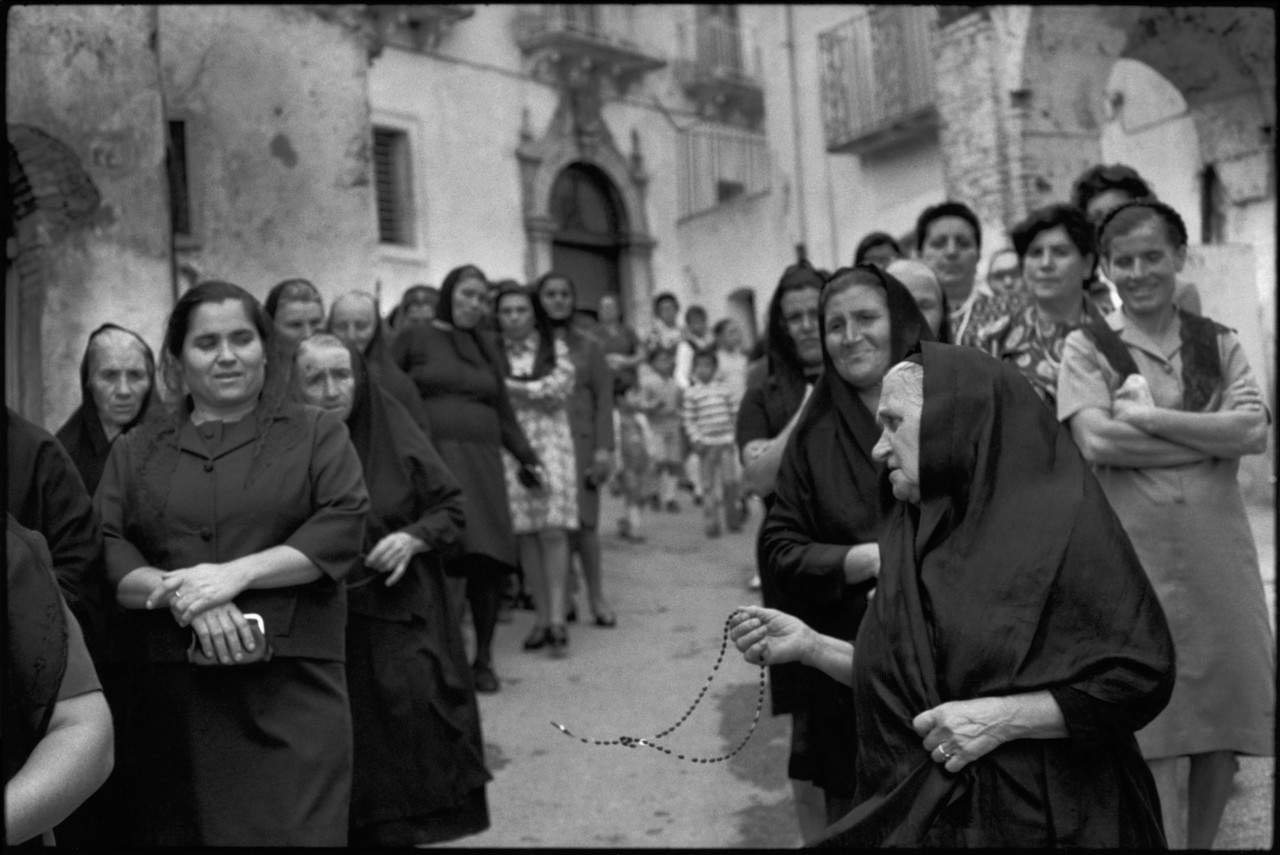

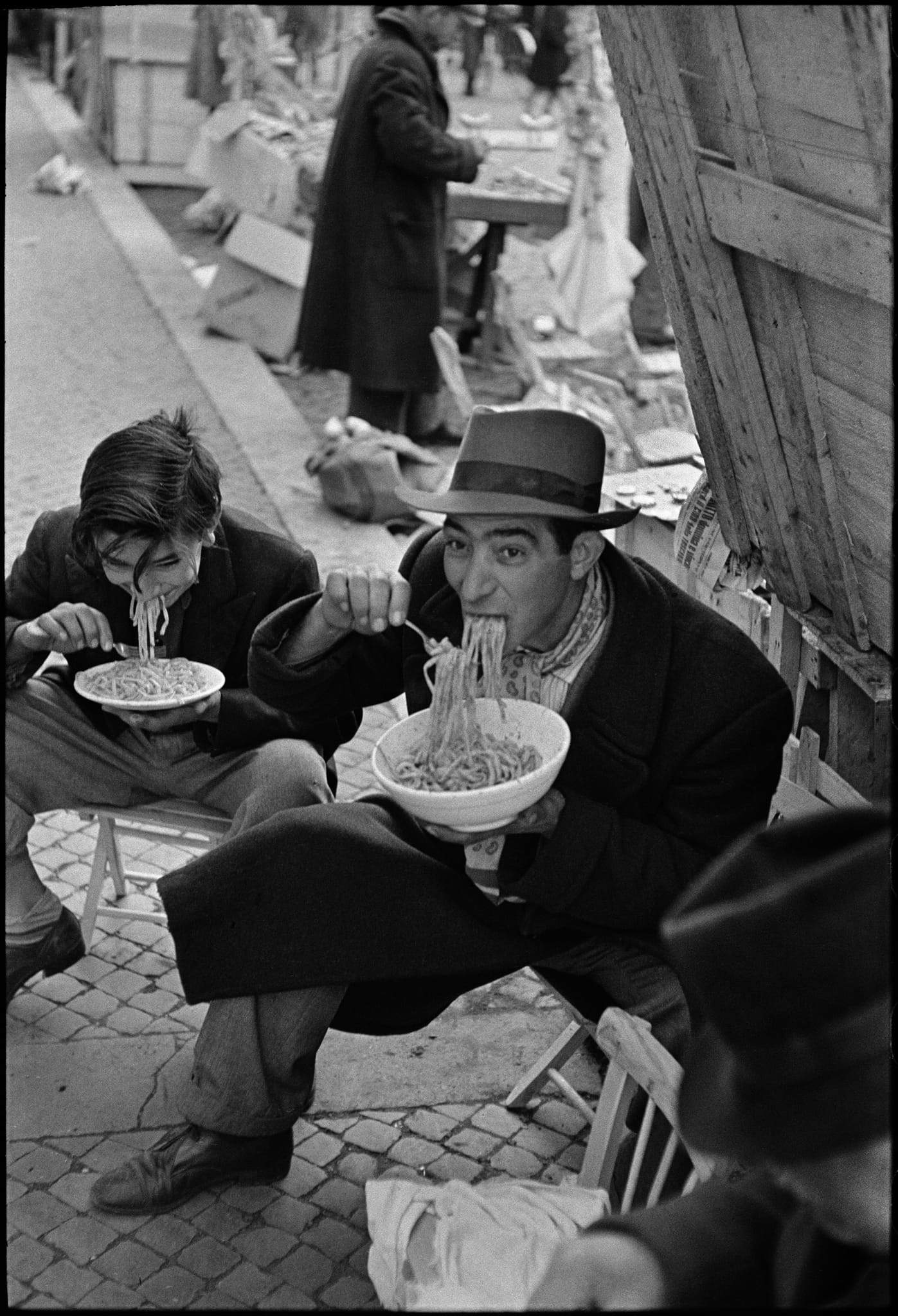

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s travels in Italy are journeys, especially to the South, recounted in photographic “reportages” that have a vague ethnographic flavor. The tone with which the French photographer approaches our worlds is somewhat reminiscent of Ernesto De Martino’s trips to the South accompanied by the photos of Arturo Zavattini, Ando Gilardi and others; scientific forays from which emerged archaic forms of local and material culture, anthropology by images if we we want to say, which documented and studied the permanences of rituals customs and traditions throughout the centuries and precisely because of this was evidence of a way of being and thinking of oneself in the humility of a social condition where the parties, after all, were reduced to a few: the powerful, the notables and the clergy, and the people who perpetuated a knowledge linked to the peasant universe, the ancestral memory, the genius loci in which rituals, women had a prominent part.

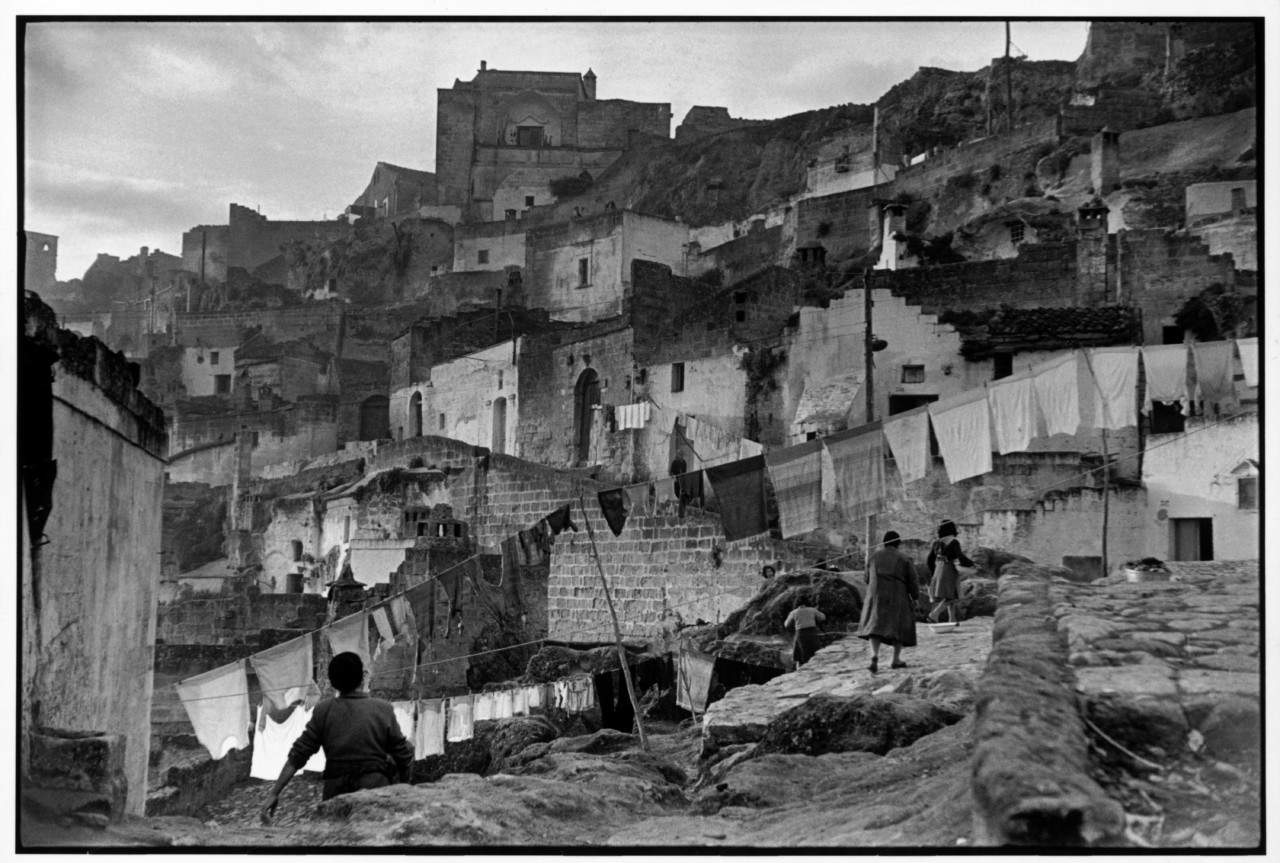

The South is the motionless body of Italy, which remains the same over the centuries, and convinced Pasolini in 1964 to film The Gospel according to Matthew among the Sassi of Matera, whose “scenography” untouched by archaic roughness even manages to become a universal image that lends its stones to a particular image, that of Palestine. The same externally restored Matera today, which still shows itself as a vertical huddle of caves (a symbol of Matera’s peasant culture and its singular way of life, and today a wonder in the face of architecture designed only to make money), as a mountain inhabited in its bowels, evoking magical atmospheres, now welcomes luxury resorts and hotels illuminated by reflected lights as a wide and prolonged poolside with the once rugged rocks now becoming as comfortable as luxury caves.

Cartier-Bresson also visited Matera twice, the last time in 1973. The cave-cellars were at the time still a sign of that Lucanian reality of magical and religious beliefs and a folklore that contrasted the old women dressed all in dark clothing with the updated way of dressing of the young with flared breeches and short-sleeved shirts. In fact, what the exhibition at Palazzo Roverella in Rovigo, curated by Clément Chéroux and Walter Guadagnini (Dario Cimorelli catalog), allows us to see at last under a single and unified photographic path is the change of Italy and, in parallel, the resistance, life clinging to its most consistent being, of the South that finds in Basilicata the theater of a particular anthropological knowledge. As Carmela Biscaglia writes in the catalog, the wide notoriety achieved in the postwar period by Carlo Levi with the novel Christ Stopped at Eboli attracted American writers, journalists and even scholars who intended to conduct sociological and anthropological-cultural research along the lines of “community studies.” There is no need to emphasize that these practices inaugurated a chapter that in the following decades would expand to Cultural Studies, which was, like many things American, a new way of thinking but also a conditioning model for those who disagreed with its sociological and ideological schematism. In particular, Friedrich G. Friedmann carried out a number of study missions and "laid the foundations of the study in an anthropological key of the Weltanschauung of the Lucanian peasants, whose dignity of a noble and civilized misery he highlighted.“ The sociologist was commissioned by Adriano Olivetti to coordinate a staff to study the city and countryside of Matera. These were precisely the years when De Martino also brought the functional use of photography, such as Arturo Zavattini’s, into ethnographic methodology: ”a founding moment of ethnography in Italy." Around a series of study initiatives was composed at the time one of the most important debates of the European postwar period, involving intellectuals, architects, sociologists, photographers and artists who have left us a repository of knowledge until then little considered, with singular and generous testimonies such as the one that linked Carlo Levi to mayor-poet Rocco Scotellaro in the narration of this heritage; or the excursions of photographers who went to Lucania to document that moment of discovery, such as Fosco Maraini, recalled by Biscaglia.

Finding myself in Matera in the summer of 2014 when initiatives were already being prepared to nominate the city as European Capital of Culture, as it would later become in 2019, I gained in that quick trip at least two certainties: the modernization of Matera and the Sassi was a sweetened, touristy form of what those caves had been for centuries, with all their bearer of the dignified humility of peasant labor and the tragic and progressive confinement of this historic experience in the schemes of the ’economy and power (if we then consider that Basilicata seems to have had the highest birth rate at the time, we should not absolve that system that over time emptied the historical memory of a very ancient culture: the “incorrupt primordial values,” as Biscaglia rightly writes); the second degree of certainty, which was also a first answer sought in my trip, was the confirmation of Pasolini’s connection with Matera since the 1950s, which led him a decade later to choose the Sassi as the setting for the Gospel (and after he had also traveled to Palestine), since, rather than environmental fidelity to a place, Pasolini pursued that “timelessness” that was to give his Christ an archaic dramaturgy that Matera’s survivals possessed and restored to those who knew how to “interpret” them for so rire . Pasolini was also photographed by Cartier-Bresson against the backdrop of the Roman suburbs, in the midst of young boys, watching them play as if he wanted to take part with them. The Gospel is the highest fruit of an identifying work carried out by Pasolini from the postwar period, when, although with a very different attitude from those who were invested with the task of making photography a handmaiden of ethnography, Cartier-Bresson also contributed to creating the atmosphere that directed our writer-filmmaker to Matera.

The French photographer was never an instrument of sociology, however active in journalistic photojournalism where his hand and eye stopped images of luminous expressive force; but his repeated presence in Italy with multi-year rhythms also leaves us with a collective portrait of our country and its people, following its transformations from the 1930s to the postwar period that prepared for the economic boom of the 1960s; and from there, to the last stage, the 1970s, where the country is no longer that world that embraced an initial modernization thanks to the aid provided by the Marshall Plan that then tied us, until today, to America (and with this “right” Friedmann and other U.S. sociologists came to do their research in the South in the 1950s). It is between 1971 and 1973, the year of the oil crisis andausterity, that Cartier-Bresson still travels through Italy. He is almost abandoning his Leica to return to painting and drawing, but he manages to give us images of the South that speak of a nation now turned to progress, especially in its clothing and industrial system. And it is still in the South that he rediscovers some of that earthy spirit that endured longest after the advent of industry that wrested labor arms from the countryside. The View of Posillipo with the two lovers looking out from a terrace at the desolate freight area; the Alfa Romeo factory in Pomigliano d’Arco; a girl in a miniskirt and a helmet of curly hair advertising gasoline by symbolically holding up the gas station pump; a sign on the wall of a building in Naples that shouts “Fascism is freedom” (which might also suggest what that many historians think, namely, that the transition from the Ventennio to democracy left many open accounts yet to be closed); on another wall, this time of a factory in Palermo, a clandestine writing calls for water for homes, countryside and industries; and then the image of two children playing in the street by running a bicycle wheel on a sidewalk and in the background car traffic with a hearse: a contrast that once again reveals Cartier-Bresson’s intuition and speed of execution even in capturing what he called the “decisive instant.” The exhibition then closes with the Sassi and some images of the Materano in 1973.

The whole composes a really important picture to read, albeit partially and according to Cartier-Bresson’s preferences that are not sociological but almost never merely aesthetic, as they are mainly “sketches” of the humanity of Italians with the chronology of his travels. Were it not for the fact that Henri was an “almost Italian” having been conceived by his parents on their honeymoon in Palerm (he will say, “the moment of conception is more important than the moment of birth”), we might consider this mosaic of his photography a collation of historical moments that follow like a seismograph the transformations of our people in the face of the insidious offerings of progress. In 1932, as an eccentric young man from a very good family, he self-portrays in Italy lying on a masonry while in the distance a woman walks away, and all we see of Henri is his right leg and bare foot. In Salerno, Siena, Livorno, and Florence, shadows and abstract signs dominate his first Grand Tour, as in a metaphysical and surreal painting that perhaps reveals sympathies for certain Italian (but also French: Derain, for example) painting in those years of magic realism. After all, Henri was painting and drawing before he did photography, and in 1928 some figure paintings have that same kind of metaphysical and surreal approach that marks a part of European painting after Cocteau’s rappel à l’ordre.

I will not go into the issues of portraiture, even of writers and artists, because they would merit as much reflection. Instead, I will conclude by recalling the “portfolio” on Rome of 1951 and 1952 with the Fox Hunt, the very curious images of the Befana festival with the policeman in the center of his lay-by as he directs traffic surrounded by boxes and things given as gifts, the little boys playing gunslingers in the street (a perfect photo of theinstant sought by Henri), the carabinieri and Roman clergy, the hairdresser’s window, the courtyards and clothes being hung out, children scattered along a staircase playing with each other; and then the first trip to Matera in 1951, all the way to Scanno and l’Aquila (these are some of the most poetic and aesthetically perfect photos, of landscape but also with the groups of women and men all in black); Bologna in 1953, and Siena, Genoa, Florence, San Remo, Venice (a city that apparently annoyed him); the Vatican with the proclamation of Pope John, and again Rome in 1958 and beyond where one can already hear emerging that populace of remarkable cynicism that has also found international fame thanks to cinema; and then Naples in 1960, and Pozzuoli to follow, and Sardinia in 1962. Thus we come full circle with what has already been said about the 1970s, where Cartier-Bresson, almost in homage to his own conception, went as far as Palermo where he also photographed Leonardo Sciascia.

Few can claim to have been able to maintain that balance between form and representation that Cartier-Bresson witnesses in photography. Perhaps his early passion for painting and drawing educated him to quickly grasp spaces, articulations, individuations, which are some of his photographic talents. He wrote that “the camera is a sketchbook, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity, the mistress of the instant who-in visual terms-asks and decides simultaneously.” It takes genius and humility to stay within this definition. A famous book of his, which in English was titled The Decisive Moment and in French Image à la sauvette, reflects an idea of photography that must capture the least unexpected instant and give us a narrative of things and man. As Lamberto Vitali wrote in 1983, “no one before him had been able to capture the moment that escapes, linking at the same time the experience of the photographer to that of the painter.” Or perhaps he did: Edgar Degas, for whom carpe diem meant nothing more than holding in the form the precipitate of life and things, reversed Cartier-Bresson’s condition: in a painting, found in the Hermitage storerooms in 1995, Place de la Concorde, where, as Kirk Varnedoe explained several years ago, the painter succeeded in rendering a multicentric perspective construction anticipating certain looks of photography half a century later. Who knows if Cartier-Bresson ever got to see it from life, he would surely have been mirrored in that paradoxical geometry.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.