Hendrick ter Brugghen's first time in Italy. What the Modena exhibition looks like

Gianni Papi and Federico Fischetti are credited with bringing and sharing with the public the most recent research on the Italian phase of Dutch painter Hendrick ter Brugghen (The Hague, 1588 - Utrecht, 1629) with the creation of the first major exhibition in Italy dedicated to the artist. It is no coincidence that the Galleria Estense in Modena was chosen as the venue for the exhibition Ter Brugghen. From Holland to Italy in the Footsteps of Caravaggio, which can be visited until January 14, 2024, because it all started here. Last year, in fact, the same Modena gallery had presented the small focus exhibition Indagini intorno a Giovanni Serodine (1600-1630). I santi eremiti della Galleria Estense e della Certosa di Pavia, curated by Fischetti and Emanuela Daffra, on the restoration of the saint he writes belonging to his museum collection, and it was on this occasion, as Gianni Papi reveals in the catalog of today’s review, that some ideas quickly matured that prompted the Modena museum to put this “ambitious exhibition” in the pipeline. For it was precisely upon seeing the restored Modena painting, exhibited as a work by Giovanni Serodine, and the Saint John the Baptist from the Certosa Museum in Pavia, exhibited as a copy by Giuseppe Vermiglio and which Papi was seeing for the first time, moreover, restored, that the scholar himself had the exciting epiphany: "the stylistic language left no doubt as to Ter Brugghen’s autography for the Saint writing about Modena,“ the curator writes. ”Very clear were those curvilinear brushstrokes, structuring the robe, as well as the unmistakable hands built with direct touches not kneaded, without drawing." And also observing, he goes on referring to St. John the Baptist, “the high quality of the very safe conducting of the fur of the saint’s legs, of the hands of the magnificent lamb, there could be no doubt that there was the autography of the Dutch painter in that painting as well.” And again, Papi writes, "with two canvases in the Charterhouse assignable to the painter from Utrecht, it was reasonable to think that the St. Paul the Hermit also concealed an image of the same artist (so many elements suggested this, beginning with the face to continue with the legs and the unmistakable feet).", but nevertheless for the latter painting he acknowledges that the quality is not sufficient to claim that it is an autograph painting, but rather a copy revealing an original (now lost) by Ter Brugghen. In the face of these new attributions by Gianni Papi of three works (one a copy) by Ter Brugghen for the Certosa di Pavia, with which Fischetti also fully agreed, the idea of an exhibition, the first in Italy, on Ter Brugghen’s stay in our country and thus on his Italian production, made possible with the support of the director of the Estensi Galleries Martina Bagnoli and Federico Fischetti, a museum official himself, was therefore launched.

In his essay For the Reconstruction of Hendrick Ter Brugghen’s Sojourn in Italy, Papi recalls that he had already dealt with the painter’s youth in Italy in 2015 and 2020, laying the groundwork for the reconstruction of the artist’s corpus, but very little data is known: his exact date of birth is not known, but he is presumed to have been born in 1588, the year his son Richard has written in the dedication on the frames of the Evangelists in De Waag Museum in Deventer; according to biographers De Bie and Houbracken, the painter stayed in Italy ten years and met Rubens in Rome, and Ter Brugghen himself stated on April 1, 1615, that he had been on the peninsula for several years and that in the summer of 1614 he was in Milan, from which he left in the fall of that year to return to Utrecht, where he had arrived by October 1.

The exhibition at the Galleria Estense in Modena is thus one that features many paintings whose attribution is due to curator Gianni Papi, including those three works mentioned so far related to the Certosa di Pavia; however, it is an exhibition that moves by hypothesis, as the curator explicitly and prudently states both in the catalog and in the exhibition: “The one in Modena is a pioneering exhibition, with several hypotheses, because the data from which to start are very few; therefore, I had to rely mainly on the linguistic contents of the paintings, on stylistic analyses, which, as we know, can meet with the aversion of those who do not understand them to the end and consequently prefer to deny the results.”

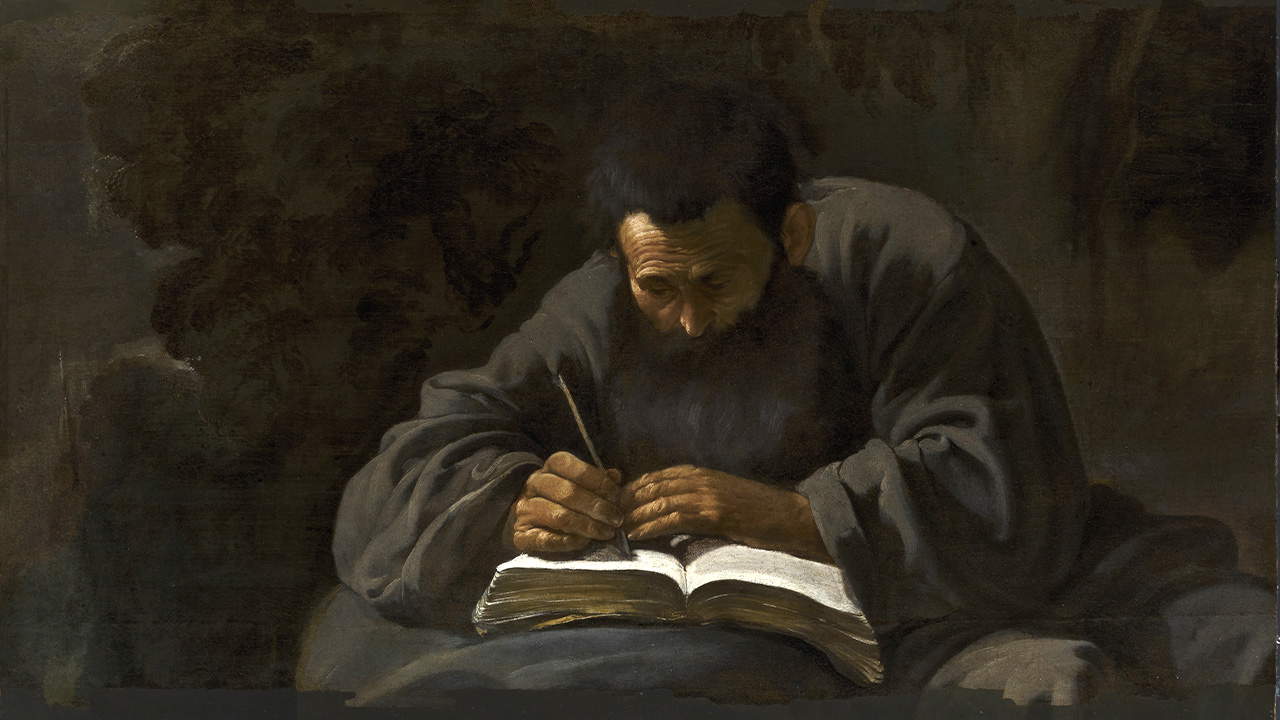

Kicking off the exhibition is Saint Writing belonging to the collection of the Modena Gallery, a work that, as anticipated, was fundamental to the birth of the monograph itself. Attributed in 1943 by Roberto Longhi to Giovanni Serodine and accepted almost unanimously by scholars this century-old attribution, the iconographic question remains unresolved, at least for the moment, since it is not clear which saint is depicted (St. Jerome? St. Augustine?). In the catalog, Federico Fischetti’s essay focuses on naturalist painting in theancient Ducal Gallery of Modena and precisely on the collecting history of the work, its ancient attributions, arriving at the hypothesis according to which the Saint who writes is identified with the Saint Augustine referred to Caravaggio, a painting first mentioned in 1657 in the Este collections by Francesco Scannelli in his Microcosm of Painting, a treatise also presented at the beginning of the exhibition itinerary. In the mid-seventeenth century in the Ducal Palace wanted by Duke Francesco I d’Este there was a nucleus of Caravaggesque paintings, evidence of the important role played by naturalist painting in that period and context, and in Scannelli’s treatise, dedicated to the duke himself, we read in the pages on Caravaggio: “One can observe in the extraordinary Galeria del Serenissimo Duca di Modana a painting of a S. Augustine of meze figures in the natural state, who stands facing with pen in hand in a most witty act, which reveals vivacity and truth truly unusual and rare.” Could this one described by Scannelli be the Saint writing already in the ducal collection? However, in 1663 it turns out to be inventoried in the rooms of the oldest nucleus of the Ducal Palace, where Scannelli had also been able to notice above a door “a picture with a gilt frame depicted in canvas by Michel Angelo da Caravaggio. It represents St. Augustine writing.” The catalog also presents a contribution by Gianluca Poldi on the diagnostic investigations carried out on the Saint Writing on the occasion of its restoration for the 2022 exhibition: the investigations allowed a comparison with the diagnostic database of Serodine canvas works that showed more discordances than coherence. In the absence of such an archive of technical data on Ter Brugghen’s works, visual observations on works permanently attributed to him and comparisons with the little available diagnostic material were made here.

The exhibition continues with large paintings that can be placed in the painter’s Italian period , such as the Negation of St. Peter from the Spier Collection, first made scholarly known by Gianni Papi, who exhibited it as a sure work by Ter Brugghen at the exhibition dedicated to Gerrit van Honthorst at the Uffizi in 2015 and five years later identified it with a painting recorded in the 1638 Inventory of the Assets of Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani as a work believed to be by the hand of Henry of Antwerp. Of nocturnal setting, the only source of light in the composition comes from the bonfire of logs in the lower left corner, which overbearingly illuminates the handmaid’s face and allows glimpses into the darkness of the other characters; note the handmaid’s white turban, which sets a precedent for Pilate’s turban in the Lublin painting of Pilate washing his hands. In the Negation it is also possible to detect a closeness to the first phase of Gherardo delle Notti ’s activity in Italy: indeed, it may have strongly influenced the latter’s early luministic experiments, though less charged. To the early years of Ter Brugghen’s production in Rome, between the end of the first and the beginning of the second decade of the seventeenth century, Papi also traces the Derision of Christ from Lille, theAdoration of the Shepherds and Salome Receiving the Head of the Baptist, both from the Spier collection, and theIncredulity ofSt. Thomas from a private collection, exhibited for the first time to the public and finding, according to Papi, obvious draftsmanship and physiognomic similarities between the apostles in the back of this painting and the shepherds in the background to the left of the SpierAdoration of the Shepherds . These are all works that the visitor can admire in the first part of the exhibition itinerary. Then there are the Portrait of a Young Man (possibly a self-portrait of the artist) from Galerie Jacques Leegenhoek in Paris and Saint Stephen from the Koelliker collection, to date the only half-figure portraits referable to Ter Brugghen’s Italian phase. Similarities in the somatic features of a shepherd from the SpierAdoration of the Shepherds have also been recognized in the latter. And again, the authorship of St. John the Evangelist, shown here, was decisively rededicated in 2020 by Gianni Papi to Ter Brugghen: this painting, too, like the Saint Who Writes, had been attributed by Roberto Longhi to Serodine (the work had a contentious attribution affair). For the curator, the St. John the Evangelist in the Sabauda Gallery presents clear correspondences with both the SpierAdoration of the Shepherds and the Negation of St. Peter, but above all he notes affinities with the canvases for the Carthusian monastery in Pavia and recognizes a physiognomy close to those of the painter’s Dutch production.

Finally, it is still due to Papi to have recognized in the Saint John the Baptist of the Carthusian Monastery of Pavia, lent on the occasion of the exhibition, the hand of another painter besides that of the Dutch artist: Giulio Cesare Procaccini , who, according to the scholar, would have made the face, with its more correggesque features, in contrast to the body executed instead by Ter Brugghen. And following this revelation, again Papi advances a collaboration between the two painters also in the Supper at Emmaus exhibited here and coming from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, since the difference in hand between the figure of Christ, particularly the face, and the disciples would be evident. As early as 1999 Alessandro Morandotti speculated on a collaboration in 1614 between Ter Brugghen and Procaccini for the figure of Christ. Among the few certain news about the Dutchman’s life is his presence in Milan in 1614, and considering this collaboration, as well as the making of the canvases for the Certosa di Pavia, it must be considered likely that the painter’s stay in Lombardy was something more important than a fleeting appearance in the summer of 1614 on his way back to Utrecht.

With a new section, the exhibition continues with works belonging to Ter Brugghen’s Dutch period after his return from Italy, but still by 1620. Here, then, is the canvas depicting Pilate washing his hands, mentioned earlier for its reference to that white turban found on the head of the handmaid in the Negation of St. Peter. The one in the Muzeum Narodowe in Lublin is a painting in which the influence of the artist’s Italian sojourn, especially of his Lombard works, is clearly discernible. In the servant pouring water on Pilate’s hands a correspondence with the St. John the Evangelist in the Sabauda Gallery is recognized (particularly in the green of the former’s robe and the latter’s cloak), while Pilate’s hands are considered “a signature ” of Ter Brugghen, since they are found in the Saint Writing, Salome, St. John the Baptist, and theAdoration of the Shepherds. And even one of the Dutch painter’s most famous masterpieces, the Vocation of St. Matthew, on loan from the Musée d’art moderne André Malraux in Le Havre, very clearly cites, albeit in an inverted sense, Caravaggio ’s masterpiece in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, yet interweaves this citation with elements that are almost Nordic, such as the feathered hat or white sleeve of the boy in the center of the scene, the crumpled papers in the background to the right, and the group intent on counting coins.

Finally, the exhibition concludes with a roundup of both artists who prompted a comparison with Ter Brugghen’s production, such as Procaccini and Serodine (the former, as noted, for the hypothesis of a collaboration between the two; the second for the attribution of some paintings now given to Ter Brugghen), as well as painters who bring out how the Dutchman was among the protagonists of that naturalistic language that sprang up in the footsteps of Caravaggio, such as Jusepe de Ribera, Dirck van Baburen, and Gerrit van Honthorst, which is realized above all in the realistic rendering of figures and settings and in a luministic rendering that plays on chiaroscuro or nocturnes with a single source of light capable of creating particular suggestions.

Despite the fact that the lighting makes it really difficult to see many of the paintings on display well, a problem that should not exist at all in an exhibition such as this one that focuses precisely on comparing elements of individual paintings and in a museum venue among the most important in Italy such as the Galleria Estense, Ter Brugghen’s exhibition in Modena gives the opportunity to admire reunited works that we could not otherwise see on Italian soil, since many come from abroad and in private collections, and to be able to observe still displayed together the aforementioned canvases for the Certosa di Pavia. It is an exhibition worth visiting, not only because of the masterpieces present (the Vocation of St. Matthew from Le Havre is one example), but also because it confronts the public with the latest research on a painter about whom very little is still known, especially about his Italian phase, and who appears to be immersed in the broad context of Caravaggesque naturalism, and thus strongly influenced by Italian painting. It is also the first monographic exhibition in Italy devoted to Ter Brugghen and the first ever to explore his Italian years, an opportunity therefore not to be missed. The catalog that accompanies the exhibition, the first catalog on Ter Brugghen in Italy, is also useful: all the works in the exhibition are accompanied by their fact sheet (an element not to be underestimated since “modern” catalogs unfortunately often tend to eliminate them); then there are essays by the two curators, Tommaso Borgogelli ’s contributionHendrick Ter Brugghen in Italy through sources and documents, and finally a section written by Gianluca Poldi on the technical investigations carried out on the Saint he writes. As Gianni Papi writes, the exhibition is meant to be “a big step forward to define some fixed points” on the Italian activity of the painter and then “to move forward from here”; to bring forth “numerous points of reflection and discussion and new paths of study,” as the director of the Estense Galleries Martina Bagnoli points out, because “one of the main tasks of a museum of ancient art is precisely to open new perspectives and encourage new encounters.” And we hope that studies and research on this painter will continue.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.