by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 21/04/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Guercino in Piacenza. Between Sacred and Profane' in Piacenza, Palazzo Farnese, from March 4 to June 4, 2017.

Among the great Bolognese painters of the seventeenth century, perhaps Giovanni Francesco Barbieri da Cento, better known as Guercino (Cento, 1591 - Bologna, 1666), is the one who best exerts his ascendancy over a vast public: certain merit of the great ductility of his brush, capable of capturing the most disparate suggestions to merge them into a unique style, easily recognizable once the eye has become accustomed to it, and in constant and constant evolution. An unparalleled versatility, one could compare her just to that of Guido Cagnacci, although the Romagnolo’s fortunes were always penalized by a life constantly spent on the razor’s edge, a problematic artistic career punctuated by defeats and an epilogue far from Italy. Guercino never had any of these problems; on the contrary: He worked for popes, cardinals and powerful varî (among whom it is worth mentioning the Duke of Modena, Francesco I d’Este), kept a flourishing workshop and, although he too experienced phases of profound critical misfortune (especially during the second half of the 19th century, following the critique of Ruskin, who in his Modern painters apostrophized theAbraham repudiating Agar of Brera by calling him “the vile Guercino of Milan,” or “the unworthy Guercino of Milan.” for the sake of the record, however, it should be reiterated that the English critic’s destructive pen affected seventeenth-century art in its entirety), he had the public, critics, and collectors on his side from the start.

This good fortune that befell Guercino, all the more reinvigorated following the studies of Sir Denis Mahon, the authentic re-discoverer of the Cento artist together with Roberto Longhi and curator of the first monographic exhibition dedicated to him (in Bologna, in 1968), is at the basis of numerous exhibitions that in recent times have seen him undisputed and often the only protagonist and that have, moreover, intensified, in the guise of tributes, following Mahon’s death in 2011: the latest, in 2015, was even a traveling exhibition that stopped in Rome, Warsaw and Zagreb. There has been no shortage, of course, of events one would gladly have done without, but that is simply the price to pay when dealing with an artist whose star is one of the brightest in the constellation of our art history and whose favor with the public is gradually rising.

Let us immediately dispel any kind of doubt to state that the exhibition Guercino in Piacenza. Tra sacro e profano, which is being held in the Ducal Chapel of Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza, belongs to the case of exhibitions with a high scholarly profile to which is added an excellent dissemination system, for a result whose quality does not come out in any way affected by the relative narrowness of the number of works on display: twenty-eight in total, arranged along a chronological path that has its greatest peculiarity in the attempt to avoid solemn deference to the divisions of Guercino’s career and to present, if anything, the evolution of his art according to that basic unity that always distinguished it and that was substantiated by the desire to adhere unswervingly to the principle of imitation of the natural learned from Ludovico Carracci (Bologna, 1555 - 1619), his first point of reference. While that extreme versatility that makes Guercino so different from so many other Bolognese painters of the 17th century obviously remains unquestionable, Daniele Benati, curator of the exhibition together with Antonella Gigli, is at pains to point out how Mahon, in elaborating a subdivision of Guercino’s career into five phases, had not resorted “to any further connotation that was not merely chronological, and therefore internal to a path that now finally appears to us to be entirely coherent.” Coherence seems to be, in essence, the watchword of this exhibition, which seeks to frame according to such a viewpoint and, consequently, according to a reading that is at all organic and therefore based on a restricted but extremely effective and exceptionally carefully selected nucleus of masterpieces, an artist for whom “the ancient imperative of seeking the reasons for the story in the confident carryover from the world around him, listening at the same time to the solicitations that come from his own heart” always applies.

|

| The entrance to the exhibition at Palazzo Farnese, Piacenza |

|

| The arrangements |

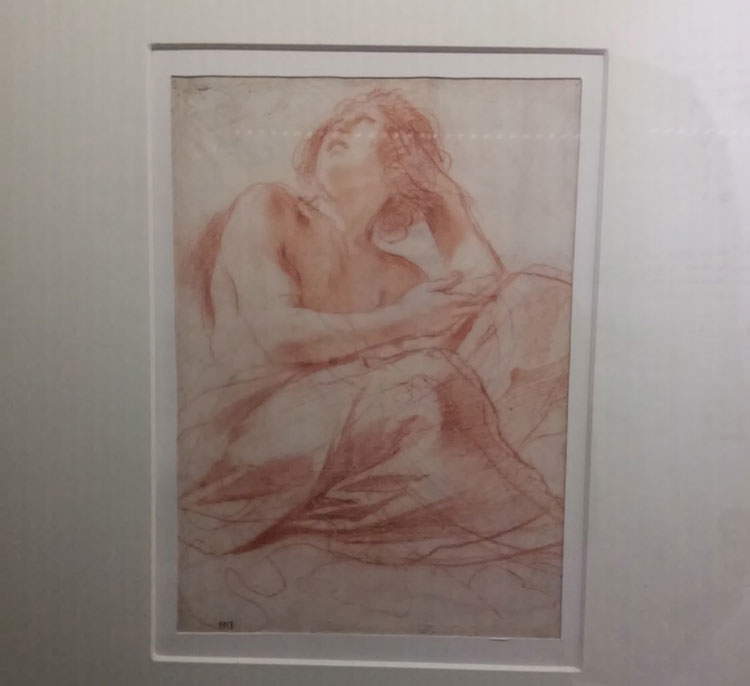

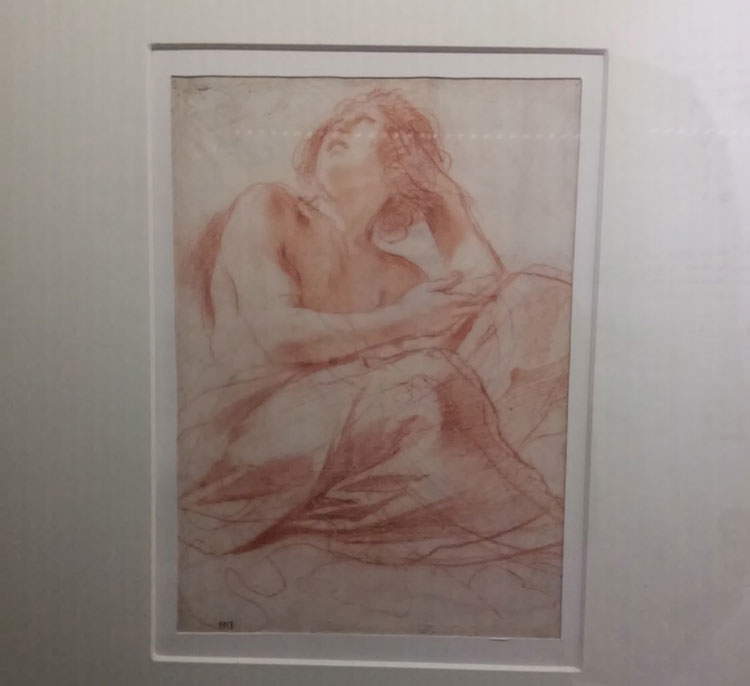

In addition to the reasons just listed, there are at least two other reasons that elevate the Piacenza exhibition to the rank of quality exhibitions. The first is the far from idle tribute to the host city and to the anniversary of the execution of the frescoes that decorate the dome of the Cathedral and that visitors, on the occasion of the exhibition and related events, can see up close by climbing up the steep stairs of the house of worship to the gallery of the tiburium, some 30 meters above the ground. The frescoes were painted in 1627 (yes, the anniversary is the number 390, so it is not a round number, but the occasion, in all evidence, will have seemed equally good to celebrate) and in the exhibition we have the opportunity to admire four preparatory drawings that came from the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe di Palazzo Rosso in Genoa. Four vivid testimonies of the meticulous and feverish preparatory work with which Guercino prepared to finish the cycle left unfinished by Morazzone in 1626, all the more precious because illustrating to the public the genesis of a work is always a meritorious operation, and all the more eloquent because they are accompanied by the excellent popularizing expedient of the panel with reproductions of the four details of the frescoes to which the studies on paper (three in red pencil, one in pen and ink with added brush and watercolor ink) refer. The second reason, on the other hand, is the presence of a painting that has just come out of restoration: it is the Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, which is located at the end of the itinerary (curiously enough, it has been placed in a sort of aulette carved out inside the bookshop) and which underwent conservation work in January 2017. The lifts were fixed, the frame disinfected, the lacerations repaired, and the whole thing finished with a cleaning operation.

|

| The drawings in the second section of the exhibition |

|

| Guercino, The Prophet Zechariah (1626; red pencil on white paper with watermark, 24 x 17.2 cm; Genoa, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe di Palazzo Rosso) |

The first part of the exhibition, devoted to Guercino’s beginnings, exhibits a good number of early masterpieces, beginning with a highly refined Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine that denounces debts to Ludovico Carracci as per the “self-certification” of Guercino himself, who always admitted to having been inspired by the great Bolognese in his approach to painting, but which also highlights, given the artist’s provenance, a resumption of the manners of Carlo Bononi (Ferrara, 1569 1632), a Ferrara painter who shared with Barbieri (more kilometer, less kilometer) his geographical origin. The profile of St. Catherine, the angled folds of the Madonna’s robe, and the clouds painted with taut brushstrokes add here to the spontaneity of gestures all Carracci-like and to the invention, also borrowed from Ludovico Carracci (in particular from a work now in Gothenburg), of the Child turning not so much toward the protagonist as toward the saint accompanying the main figures (Carlo Borromeo in the Guercino painting: in Carracci it was St. Francis instead). A painting of closer Carracciesque observance would come a few years later, following the painter’s momentary move to Bologna, where he was able to closely observe the results of Ludovico Carracci’s painting and have fruitful encounters with him: the St. Bernardine of Siena and St. Francis praying before the Madonna of Loreto belongs to this period, that is, about three to four years after the above-mentioned Marriage. Still from Ferrara are the putti above, an almost literal quotation from a painting by Scarsellino (Ferrara, 1550 circa 1620) made for the convent of Santa Maria Maddalena delle Convertite in Ferrara and now in Houston, but deriving from Ludovico Carracci are the taste for the natural the devout atmosphere, the gesture of St. Francis borrowed from that of the same saint Carracci painted in the Cento altarpiece, and again “lampiazza of gestures, scaled in depth according to the powerful trajectories” of Carracci and pupils (so Benati in the catalog’s file on the painting). A symptom, on the other hand, of a personal taste that will be better developed in the years to come, is that luminism that produces striking contrasts between areas of light and areas of shadow (see, paying attention to the spotlights that cast glare on some of the large-format works, making it necessary to find an optimal vantage point, the statue of the Madonna, cut in two by the shadow cast on her by the drape of cherubs). Sealing off this first section and pointing to further assimilation by the young Guercino is the Uffizi Concert, with a distinctly Venetian theme that reached the Cento artist probably through Dosso Dossi, who, as is known, was active in Ferrara for a long time, and perhaps also through the engravings of Domenico Campagnola.

|

| Section devoted to early works |

|

| Guercino, Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine in the Presence of Saint Charles Borromeo (1611-1612; oil on panel, 50.2 x 40.3 cm; Cento, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Cento) |

|

| Guercino, Saint Bernardine of Siena and Saint Francis of Assisi praying before the Madonna of Loreto (1618; oil on canvas, 239 x 149 cm; Cento, Pinacoteca Civica Il Guercino) |

|

| Guercino, Country Concert (ca. 1617; oil on copper, 34 x 46 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

The section dedicated to the 1920s (“The years of fame,” according to the curators) hosts some of the most celebrated masterpieces of Guercino’s entire production, starting with the very famous Et in Arcadia ego, a painting that has been the protagonist of many exhibitions on Guercino because of its undoubted load of suggestion, disquiet, mystery, and of course because of the jarring between the amenity of the landscape and the sinister detail of the skull eaten by rodents. Looking at the paintings after his stay in Rome, dated 1621, during which, moreover, Guercino shared the same residence with the aforementioned Cagnacci, one can also guess why the Cento artist exerts a fascination that has now become magnetic even on a public unaccustomed to 17th-century Emilian art: many scholars have discussed Guercino’s relations with the art of Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610), and the Piacenza exhibition is also a further opportunity to reflect on the subject. The St. Matthew and the Angel, a striking work on loan from the Pinacoteca Capitolina, could not be explained if not on the basis of a meditation on Caravaggio’s light (“albeit mediated and re-educated by the manners of his epigones still active in Rome,” Massimo Francucci points out in the catalog), and the same goes for the celebrated Apparition of Christ to His Mother: that curtain appearing in the upper right corner would seem to come from the Death of the Virgin by the great Michelangelo Merisi. The two great souls of Guercino’s painting coexist here, for though close to the natural that always characterized his research, he emerged, if anything, with new suggestions from his confrontation with Caravaggio, and that here, as in so many other works by Guercino, is especially noticeable in the hands of the protagonists (such an anatomical element is perhaps the one that, in all of Guercino’s production, most and best betrays his search for the natural), the work is animated by those concepts of “idealization” and “simplification” that Mahon used to propose a comparison with Guido Reni and to trace affinities and differences. The latter, in particular, would be to be found in Guercino’s failure to resort to the antique and in the more violent (pardon the adjective) light-shadow games of the centese. One could speak of a balanced “natural,” in short, kept under tight control.

|

| Section devoted to the years of fame |

|

| Guercino, Et in Arcadia Ego (1618; oil on canvas, 78 x 89 cm; Rome, Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica) |

|

| Guercino, Saint Matthew and the Angel (1622; oil on canvas, 120 x 180 cm; Rome, Musei Capitolini - Pinacoteca Capitolina) |

|

| Guercino, Apparition of Christ to His Mother (1628-1630; oil on canvas, 260 x 179.5 cm; Cento, Pinacoteca Civica Il Guercino) |

The large canvas of theApparition then introduces us to what is the leitmotif of the last section of the exhibition (“The Years of Glory”), namely the taste for theater that distinguished much of Guercino’s production and that does not fail in his extreme phase: it is on this aspect, more than on the classicist turn of the last years, that the Piacenza review seems to insist most. A theater of feelings, to be sure (and theApparition is an excellent example), but one that often becomes concrete theater, as in the magnificent Cleopatra in Palazzo Rosso, one of the artist’s best-known achievements and probably also the most theatrical strictu sensu of his entire output. A jubilation of gestures, hinted at but also blatant, elaborate poses, sometimes languid, sometimes moved gazes, that leads the protagonists of the works to emotionally involve, as Benati again points out in the catalog, the viewer (particularly, the scholar notes, in the early years of his activity, but it is a specification that continues throughout Guercino’s career). The intense and sweet beauty of the Susanna violated by the two old men and who, without losing faith and control for a moment, turns her gaze to heaven to seek comfort, the tenderness of the Saint Agnes who almost with awe stares at us who in turn look at her, and again the profound humanity of the Immaculata who plows through a sea illuminated by poetic moonlight (one of the most beautiful of the seventeenth century) on her little cloud are, in this sense, true summits that the curators have been able to bring together in an exhibition that is among the most successful in recent years.

|

| Guercino, Death of Cleopatra (1648; oil on canvas, 173 x 238 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova, Palazzo Rosso) |

|

| Guercino, Susanna and the Old Men (1649-1650; oil on canvas, 133 x 181 cm; Parma, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Guercino, Saint Agnes (1652; oil on canvas, 117 x 96 cm; Cesena, Galleria dei dipinti antichi della Fondazione della Cassa di Risparmio) |

|

| Guercino, Immaculate Conception (1656; oil on canvas, 259 x 180 cm; Ancona, Pinacoteca Civica Francesco Podesti) |

One more Guercino exhibition, then? Yes and no. No, because we are able to say that the Piacenza exhibition differs from many of the recent events devoted to Guercino: the examples of the “tripartite” exhibition mentioned in the opening, which had, if anything, another merit, namely that of bringing out of the Pinacoteca di Cento damaged by natural events more than twenty of the artist’s works, which represented two thirds of the works on display, and making them known in three countries, or again the small event in Cento in 2014 dedicated to the relationship between the artist and music, or the Bologna exhibition in 2009 dedicated to the artist’s youthful production. Yes, because Guercino is a complex artist, because new things emerge from the exhibition (few, but present), because the review is well accompanied by the opportunity to see the frescoes of the Cathedral up close, because it does the artist good to have a reinterpretation of his path founded on a now well-solid basis, taking into account the latest studies, and presented, moreover, with a popular project (with scenic, but sober settings: very interesting is the corridor with some sentences on Guercino taken from writings by great scholars such as Mahon, Longhi, Gnudi, and Cavalli) that can only benefit the public. Finally, the well-structured catalog published by Skira presents, in addition to the good introductory essay by Benati and the well-prepared descriptions of the paintings, a contribution by Susanna Pighi dedicated to the frescoes in the cathedral, a valuable photographic atlas of the dome, the result of a very recent photographic campaign, an essay on the restored St. Francis and a sort of “guide”, written by Manuel Ferrari, to the route from the cathedral to the dome.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.