From Group 63 to Group 70: in Spezia staged the moving reunion of a group of losers

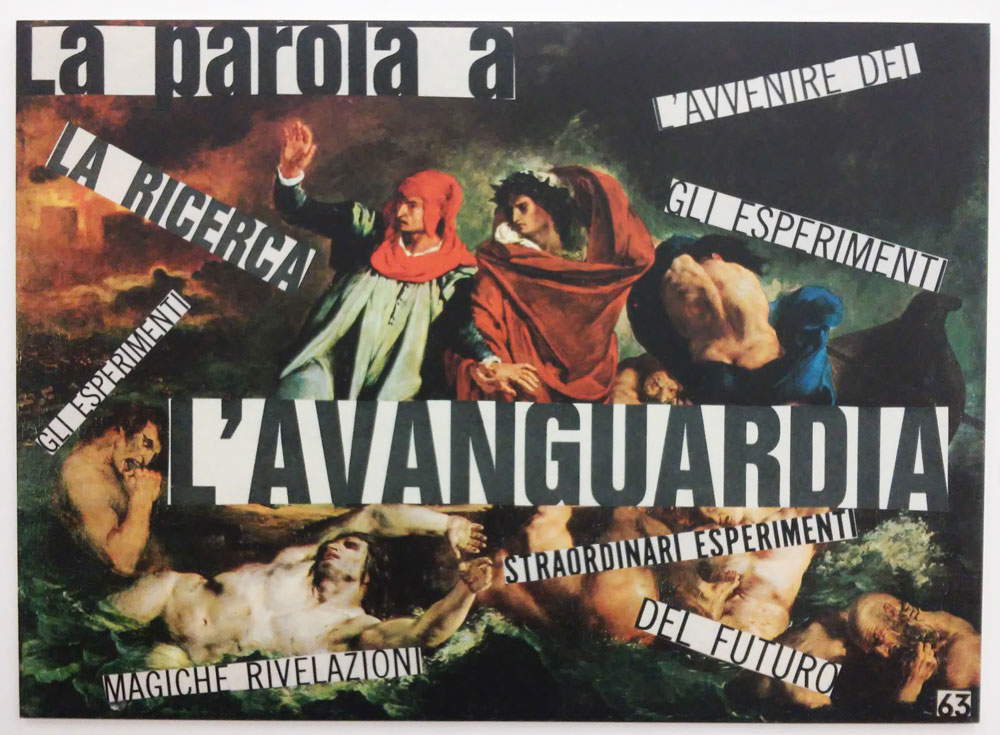

What is theavant-garde? For Nanni Balestrini (Milan, 1935), the definition can be broken down and then succinctly summarized with a few basic words. Research. Experiments. Magical revelations. Extraordinary experiments. Of the future. The future. All combined with a number that serves as a vindication: 63. A mosaic of serif characters taken from newspapers and magazines, scattered over Delacroix’s Dante’s Boat, elects Alighieri as history’s first avant-garde artist and gives birth to one of the most significant works among those on display at the exhibition From One Avant-Garde to Another. Verbo-visual Experiences between Group 63 and Group 70, running until March 19, 2017 at CAMeC (La Spezia). An exhibition, curated by Renato Barilli, halfway between history and current events, where the works of the beginnings and the current research of a group (or rather: two groups, which then were not groups) of avant-garde artists of the 1960s are united in a mélange that in the end a little tells and a little makes one reflect. And perhaps even manages to move.

|

| Exhibition entrance |

|

| Nanni Balestrini, The Avant-Garde (2014; inkjet on canvas; Florence, Galleria Frittelli) |

Because looking at these works in 2017 is a bit like dancing to a Jesse Green song: stuff for those who were there at the time, or for those who like to think back to a past they didn’t live through, or for maniacs, of 1970s disco as of 20th-century art. Seeing still at work artists-poets worthy of all praise such as Nanni Balestrini, Lamberto Pignotti (Florence, 1926) and others who, past the age of eighty, even today oppose their visual poems to a reality made of viral videos and social networks (by the way: but were social networks avant-garde?) comforts and discourages at the same time. It comforts because making visual poetry in 2017 is almost a heroic act: a profound rapidity and an intelligent synthesis against the idiocy of the vast majority of tweets, against the superficiality of aesthetic populism (to use an effective expression by Gabriele Pedullà ), against the arrogance of the former avant-garde that has institutionalized itself in the worst way (it is enough to walk a few dozen meters to find oneself in front of Daniel Buren’s highly contested car wash in Piazza Verdi). Group 63 itself has also institutionalized (otherwise it would not be exhibiting in a municipal museum with the approval of the authorities), although this is the price to pay for having entered the history of literature and even art. But it is comforting because some of the original members of Gruppo 63 and Gruppo 70 have remained, as they say, true to the line, and have not expired in the allology of articles for readers tuned in to faux Fazio-style cultural insights, in art modeled for the use and consumption of the market, or in mannered trombonism perhaps entrusted to technological means considered new but which are then not so new. Or it simply has not disappeared from the cultural radar, despite the fact that the signal is weak. It is discouraging because not only do avant-gardes no longer exist today (whatever some may say) but, if it is true what Tomaso Montanari asserted a few days ago, namely that artists today are socially irrelevant and that power is in the hands of the market, they are probably no longer even possible. In short, that kind of prophecy that Pignotti had launched with his 1964 Fantastico came true: a picture of a housewife and a café with two cutouts next to it that read Gli uomini di cultura passano all’offensiva and Non succede mica niente.

|

| Lamberto Pignotti, Fantastico (1964; collage on cardboard; Prato, Carlo Palli Archives) |

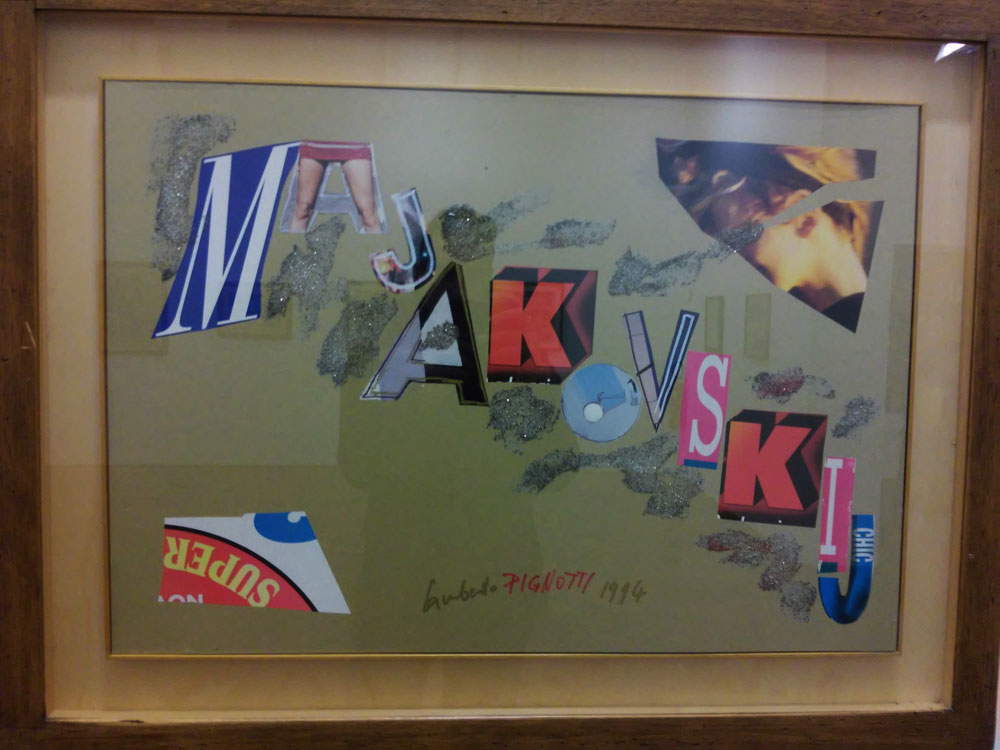

Thus an exhibition that smacks of a reunion is staged in Spezia. Because, to tell the truth, there was a reunion: in October the veterans of the Group met for a conference of nostalgia and memories, which Barilli summed up in one of the few articles on his blog that can be considered readable. And to tell the audience about how, exactly fifty years ago, the Group had held its fourth reunion on the very shores of the Gulf of the Poets: remembrance which, they point out, is not celebration. From that meeting emerged, in particular, the figures of Lamberto Pignotti and Lucia Marcucci (Florence, 1933), founders (in the same year 1963 as Group 63) of that Group 70 that set itself longer-term ambitions and, above all, attempted an approach that, compared to that of its colleagues, was less cerebral, more immediate, more attached to reality. Low culture manipulated to give birth to a high result. A middle ground between art and literature: a bit like seeing a work by Lichtenstein bent to the ways of Majakovsky’s poetry. And it is no coincidence, moreover, that the La Spezia exhibition displays a tribute by Pignotti to Majakovsky, to give credit to the poet who, together with Rodchenko but also alone, composed some of the first visual poems in history. Two of the exhibition’s four rooms are devoted precisely to Pignotti and Marcucci. The first, on the other hand, is a summary of the production of Nanni Balestrini, one of the founders of the group: there we find a fifty-year leap between the first visual poems of the 1960s, coeval with the founding of the Group, and the latest research, which runs from 2012 to the present. Finally, the last room welcomes experiences of perhaps the Group’s most sophisticated artists, those who did not go on to replenish the ranks of the “70s” and who kept to a production that had more in common with French Lettrism: Vincenzo Accame, Antonio Porta, Luigi Tola.

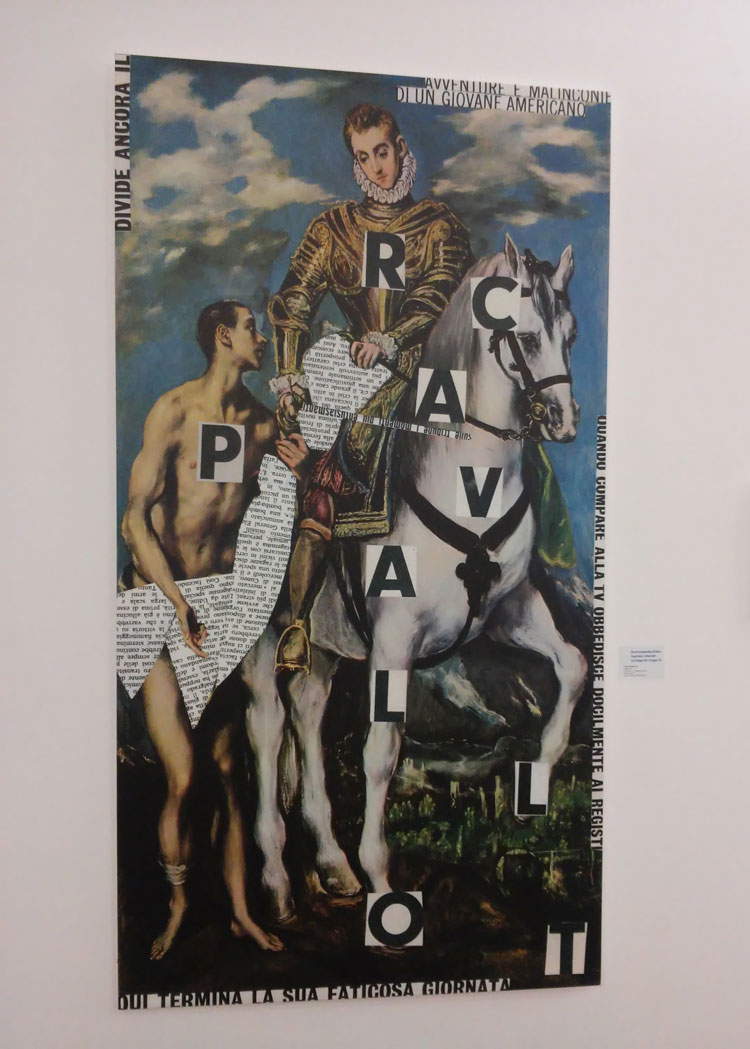

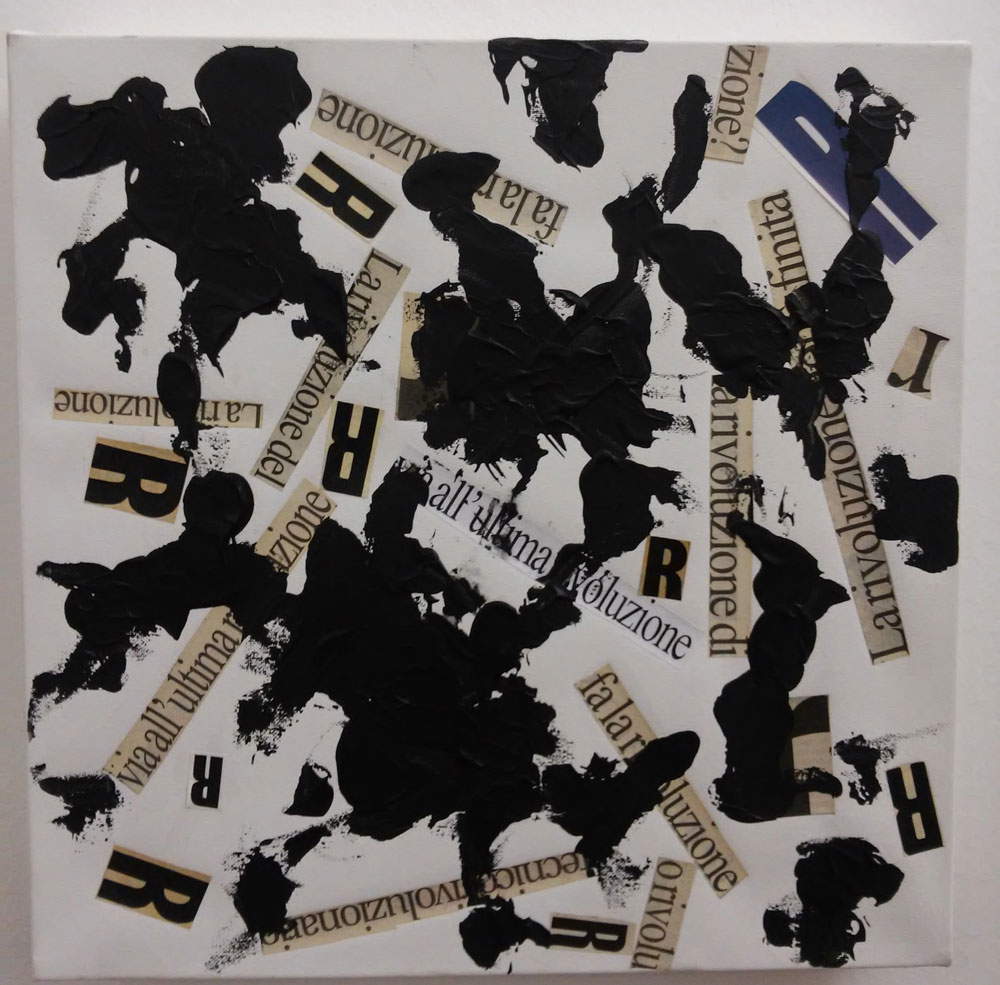

The ambition of these artists was to take literature out of the book: to abandon a place at the time still typical of high culture and drive poetry downward, exploiting the strategies of mass communication. This is the basis that gives birth to the most interesting and original experiences of Group 70, and the early works of Nanni Balestrini have the task of introducing the visitor to the exhibition. “If the public does not seek poetry, poetry must seek the public,” Pignotti echoed, reversing in intention, and also in practice, a famous assumption by Wilde. The Qualcosapertutti series of the 1960s, with which Balestrini began to propose his own visual poems, “uses as a background the large color photos of weekly gravure magazines of the time, when photography was a privileged means of communication” and exploits, to communicate, the technique of collage: a late return futurism for some, a sum of Picasso, Mallarmé and Schwitters for Balestrini himself but also for those who were able to grasp the novelty of this approach to poetry. The desire to experiment continues to this day: the Masters of Color cycle rereads some masterpieces of the past according to the typical ways of Group 70. Arthur Danto said that the work of art, being the result of an intention, must necessarily have an object, which must be interpreted. Balestrini adds newspaper clippings to the works, sometimes to reread them in an ironic key, sometimes to elevate them to a symbol (we saw this with the Delacroix work mentioned above), sometimes to better extrinsicate a meaning: in San Martino del Greco two large letters, a P (poor?) and an R (rich?) are placed at the height of the hearts of the painting’s two protagonists, and all around them newspaper clippings that actualize the parable of St. Martin and the poor man and perhaps reverse its meaning, as if the knight’s gesture, from disinterested, becomes a forced, almost exhibitionist act. The Blacks, newspaper clippings on white backgrounds smudged with black ink stains, destroy and recompose to show that, despite everything, the avant-gardist still harbors a certain confidence: I break but I do not bend. The revolution is not over. Off to the last revolution.

|

| The room with the works of Nanni Balestrini |

|

| Nanni Balestrini, Horse (2014; inkjet on canvas; Florence, Galleria Frittelli) |

|

| Nanni Balestrini, Mi spezzo (2013-2014; mixed media on canvas; Florence, Galleria Frittelli) |

|

| Nanni Balestrini, La rivoluzione (2014; mixed media on canvas; Florence, Galleria Frittelli) |

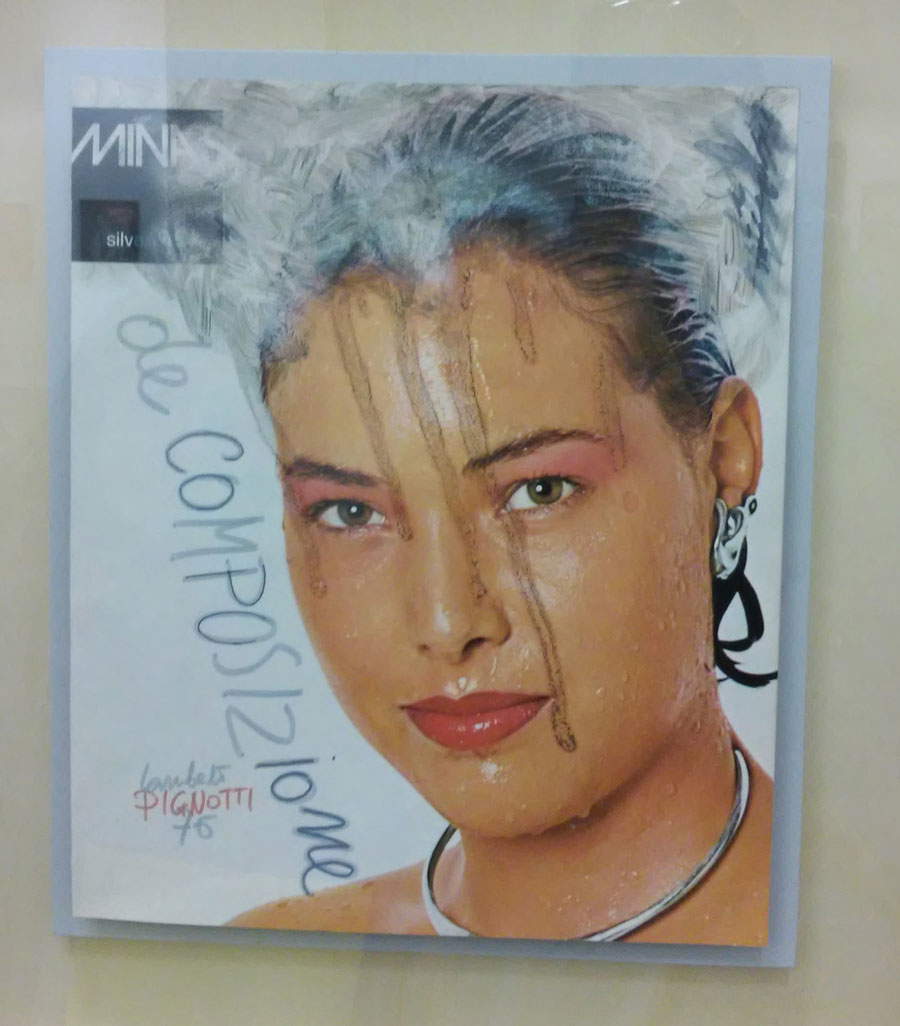

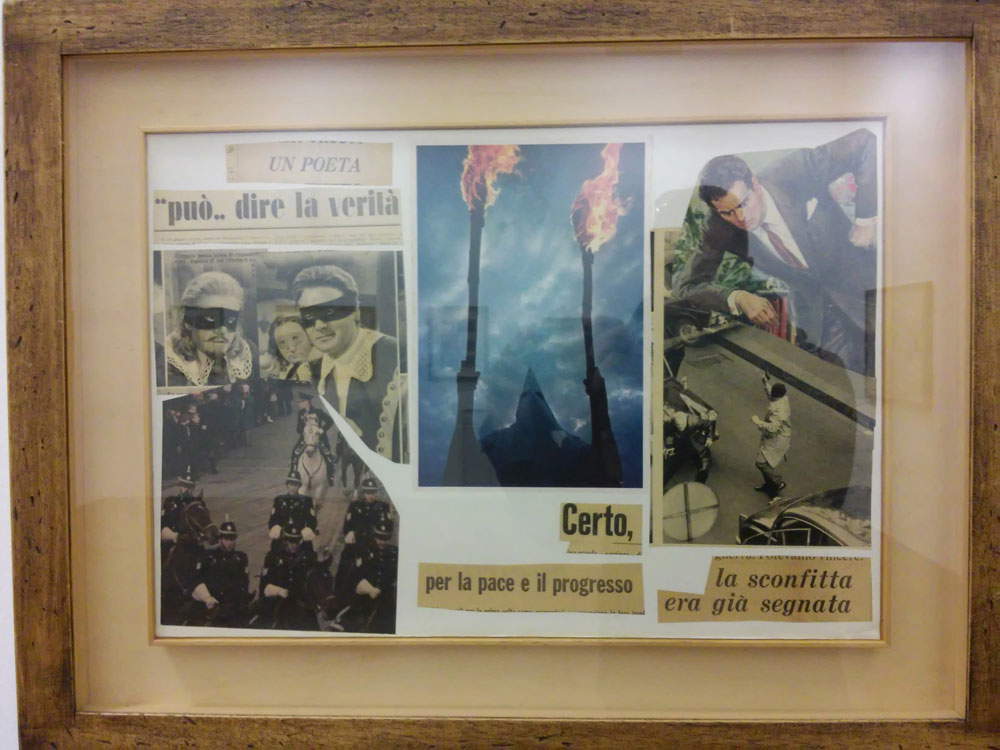

Pignotti and Marcucci start from advertising, perhaps the most typical language of mass society, as well as one of the means that power and capitalism use to subjugate the recipients of the message: the goal is to “send the goods back to the sender,” in Pignotti’s words, and to transform into an active subject (who does not just look, but after looking interprets and thinks) the passive subject who undergoes the repertoire of advertising communication (or marketing, we would say today). Pignotti uses the medium of parody by proposing irreverent reinterpretations of images that are typical of the visual repertoire of advertising and that aim to make fun of (but also condemn) stereotypes, power, consumerism, and the abuse of art and culture. Using advertising to make the audience realize how deceptive advertising itself is. Decomposition is a burlesque protest against female beauty standards from cosmetic advertisements: a stream of ink trickles down a beautiful model’s hair, ruining her make-up and revealing aesthetic deception to the viewer. Instead, it tries to shake up the collage You’re Still on Time, which combines images of crowds with a frame made of clippings featuring models wearing clothing: I will not write for those who are poor without a defined trend, the clippings emphasize. There is also time for a reflection on the role of the poet in contemporary society: in The poet “can” tell the truth? the title of the work, again taken from newspaper clippings, is accompanied by the phrase Of course, for peace and progress the defeat was already marked pasted next to five images (the three musketeers, a British military parade, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, a richly dressed character and a gunfight).

|

| Lamberto Pignotti, Majakovsky (1994; collage on cardboard; Prato, Carlo Palli Archives) |

|

| Lamberto Pignotti, Decomposition (1976; mixed media on printed paper; Prato, Archivio Carlo Palli) |

|

| Lamberto Pignotti, Un poeta “può” dire la verità (1966; collage on cardboard; Prato, Archivio Carlo Palli) |

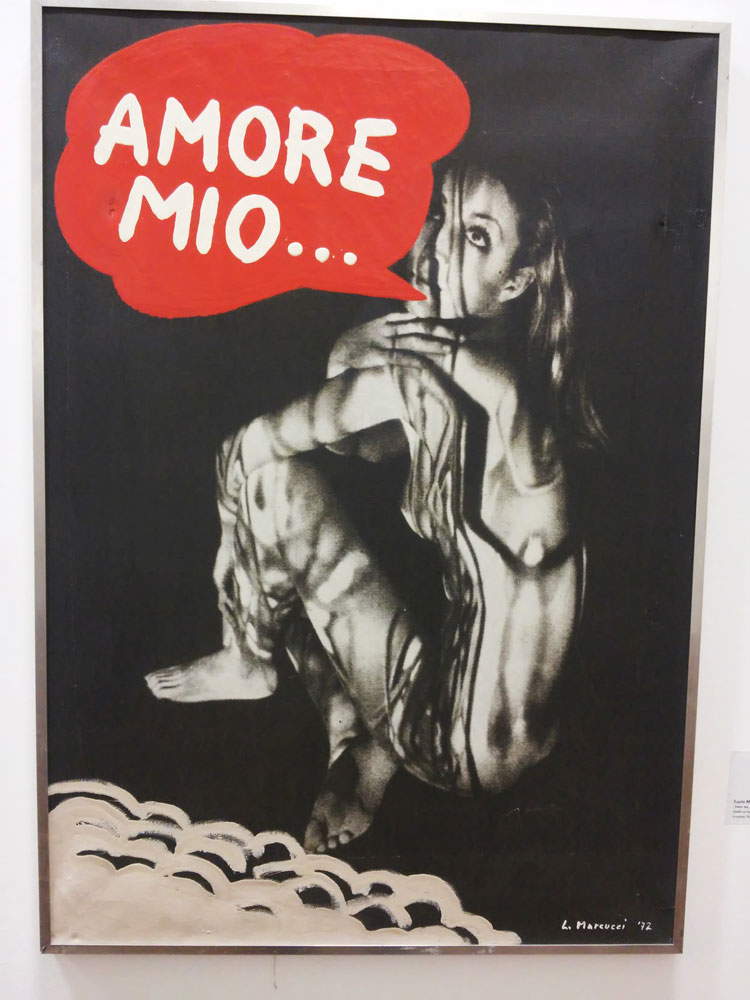

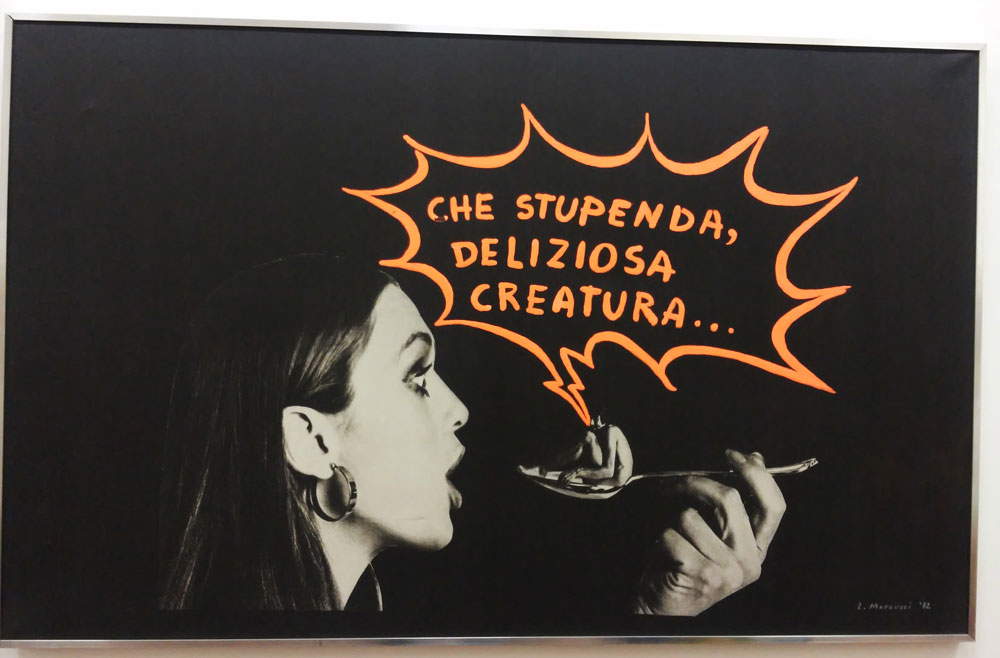

Lucia Marcucci’s critique is even simpler and more direct. Thick markers and acrylic colors are the means through which the artist expresses herself by modifying images that become slaps in the face of the observer: more than the structure of the whole, what matters is the strength of the message. A naked girl leans against a wall: it looks like an image of those that in newspapers they put to fill articles about violence against women. She looks in front of her, looking almost intimidated. But in front of her is a red comic strip: My Love. Of a totally opposite sign is a work from the same year: another young woman (probably the same one, she looks very much like her) carries a spoon with a cowering man on it to her mouth. What a wonderful, delightful creature. But she is about to eat him. And then reflections on love and sexuality, topics always creeping into Lucia Marcucci’s decades-long output. Or on the relationship between man and woman. The vices of society that spill over into intimacy.

|

| Lucia Marcucci, Amore mio (1972; enamels on emulsified canvas; Prato, Carlo Palli Archives) |

|

| Lucia Marcucci, How stupendous! (1972; arciles on emulsified canvas; Prato, Carlo Palli Archives) |

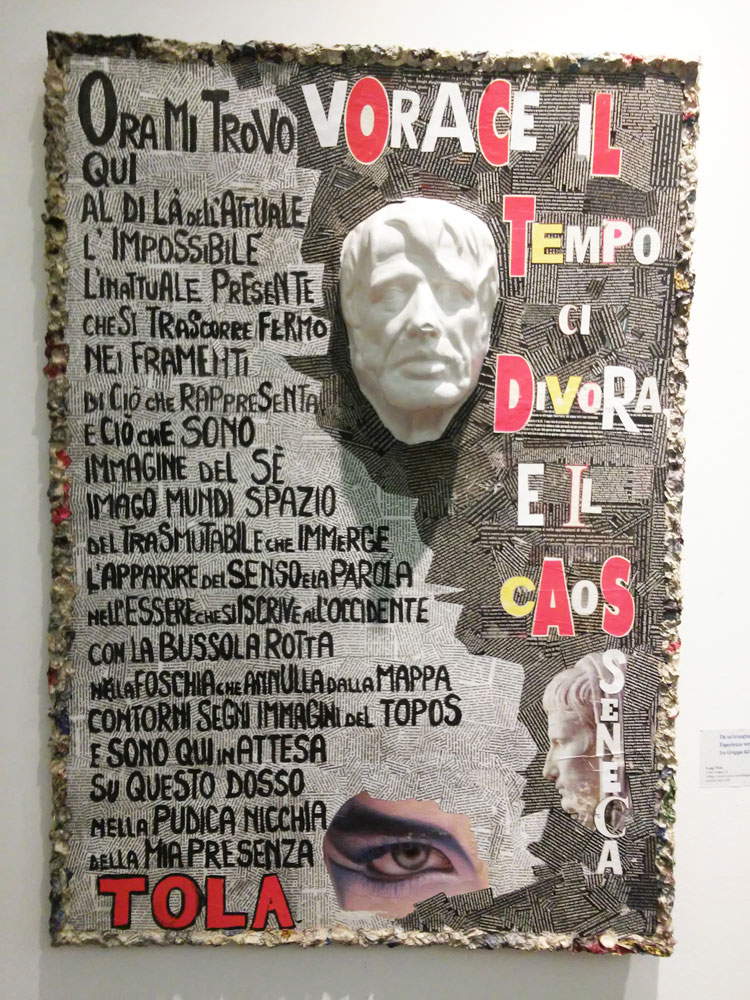

The last room of the exhibition flows by rather quickly: works by members of Group 63 who are no longer with us are displayed there. The visitor is captivated by the works of Luigi Tola (Genoa, 1930 - 2014): a rough texture, made of cutouts with tiny characters, is the carpet on which the poet vents his aggressive creativity to propose, paradoxically, a lyricism that, although not refined, is still far from the ironic parodies of Balestrini, Pignotti and Marcucci. Tola does not go toward the audience by using a language familiar to the public: the Genoese poet quotes Seneca’s Troad (even physically: a portrait of the great Roman playwright emerges from the painting) to reason about time through a text that seems to have been carved with an axe, but exudes passion from every single letter. The work of Vincenzo Accame (Loano, 1932 - Milan, 1999) is exceptional chirographic exercise with more than a debt to Lettrism. With his visual writing he has made the word a graphic sign that registers sensations in the form of images that have an almost musical progression: observing Vincenzo Accame’s signs is almost equivalent to listening to a symphony.

|

| Luigi Tola, Voracious Time (q.d.; collage and mixed media on plywood; private collection) |

|

| Works by Vincenzo Accame in the exhibition |

What is left today of Group 63 and Group 70, beyond a group of nice and lucid over-eighty-year-olds who inside, by their own admission, still feel young, still feel the passion they had in their twenties, thirties, forties? What is the legacy they have left, other than those words that escape from the pages and go to hang on a wall addressing messages to us in a language that has now been supplanted by other (even more basic, certainly more childish) forms of communication? Probably little, one would think. Umberto Eco, in an interview he gave to Repubblica shortly before he left, lamented the fact that among literati today there is a lack of taste for confrontation. At a time when the primary goal of many writers seems to have become to pursue commercial success (a success that, moreover, has arisen for Eco himself: I am convinced that we would very happily have done without the vast majority of his output), and possibly to pursue it alone, it is difficult to imagine groups of poets and storytellers coming together as a group, even with an undefined agenda, to try to change the fortunes of literature or even, more simply, to engage in social criticism. Modern-day publishing, which exacerbates competition among writers, simply does not allow this. What remains today is, essentially, a group of losers, but losers in the literal sense of the word, because Group 63 had among its ambitious goals to change the country through literature. They tried with a chaotic , messy, short-lived, and unrealistic revolution. But this goal has been lost today, in the sense that it is very hard to find someone who still pursues it with conviction, and it is practically impossible to find someone who pursues it and is successful at the same time. In short, there is a lack of someone who tries to subvert the canons of literature, who triggers ruptures. What survives, then? Memories. Attached to the white walls of an exhibition that seems almost like a long sigh, and combined with a certain ability to push opponents to controversy (even fifty-plus years later, and on a de facto finished experience). The desire to continue to produce, even in the knowledge that we are no longer in ’63. The desire to continue to make people think. And perhaps an invitation to seek out (obviously at the margins) and recognize those who are still trying to experiment today.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.