by Ilaria Baratta , published on 08/12/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Giuseppe Diotti. A protagonist of the 19th century in Lombardy' in Casalmaggiore, Diotti Museum, until January 28, 2018

It is not easy to find an exhibition set up in the same place where the artist lived and created part of his works: this is a strong point for the review that Casalmaggiore, a small town not far from Cremona, is dedicating until January 28 to one of its most illustrious sons, Giuseppe Diotti (Casalmaggiore, 1779 1846). An artist glorified in his era, between the end of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, so much so that he earned the honors of Defendente Sacchi, among the most important and authoritative art critics of his contemporaries, who wrote in 1832: Diotti is the best painter in Lombardy and some believe even the best who paints in Lombardy: fashion gives the palm to Hayez and Pelagi, perhaps time will give it to Diotti...: however, after his death he was neglected by critics and today, unfortunately, few remember him.

Only in 1991, thanks to Renzo Mangili who curated the unforgettable exhibition in Bergamo Giuseppe Diotti. In the Academy between Neoclassicism and Historical Romanticism, interest was reawakened in that first Lombard painter, as Defendente Sacchi still called him, recognizing his primacy in the revival of the ancient fresco technique and in the realization of sacred painting, represented by the artist in a skillfully innovative way for his time. It continues along the same lines lattuale exhibition in Casalmaggiore, which synthesizes Giuseppe Diotti. A Protagonist of the Nineteenth Century in Lombardy, and which intends, if not to restore Diotti to his former praise, at least to make one of the greatest exponents of Lombardy’s nineteenth century known and reappropriated. The exhibition is also intended as an invitation to admire the protagonist’s works also in places of worship and culture in neighboring territories: visitors will be able to follow some of the itineraries proposed on the occasion of the retrospective in order to arrive at a broader vision and knowledge of the masterpieces created, which would otherwise remain confined to the exhibition route alone. Admirable idea.

|

| A room of the exhibition “Giuseppe Diotti. A protagonist of the 19th century in Lombardy.” |

|

| A room of the exhibition “Giuseppe Diotti. A protagonist of the 19th century in Lombardy.” |

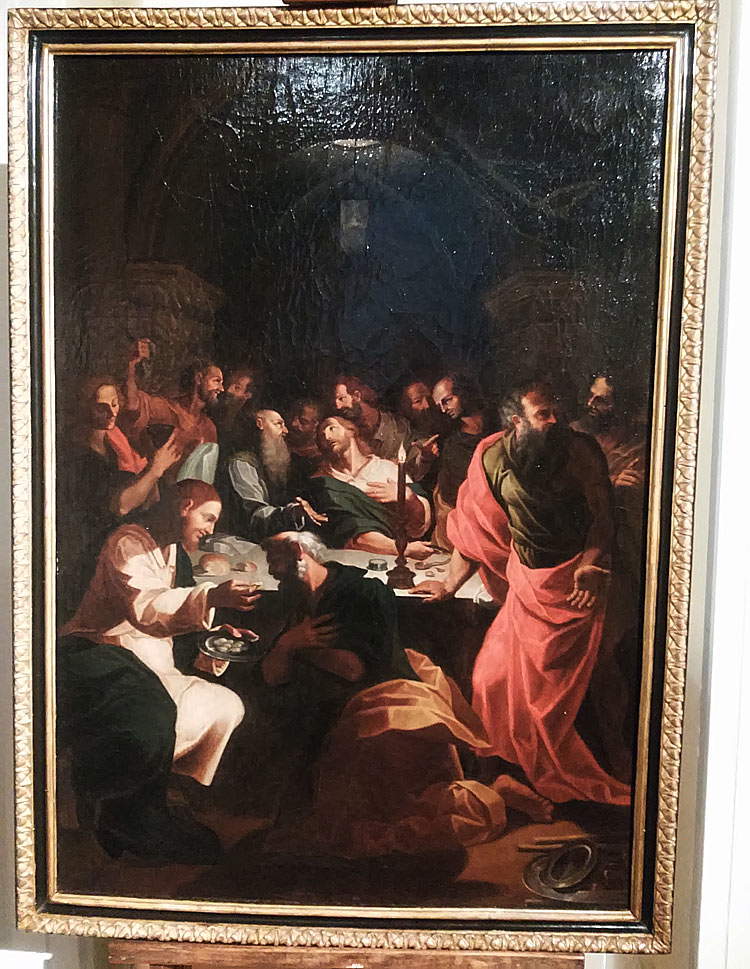

The itineraries will take visitors to the provinces of Lombardy where the artist worked during the course of his activity, particularly on the Casalmaggiore-Cremona-Bergamo axis: Examples include the Cathedral of Santo Stefano in Casalmaggiore, where the high altarpiece depicting the Madonna with St. Stephen and St. John the Baptist is located, the subject of which is reminiscent of Parmigianino’s painting done in 1540 for the old church of Santo Stefano, now housed in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden, as well as the large canvas of the Flagellation of Christ from 1802 and two works made by Gian Battista Trotti, known as the Malosso, copies of which Diotti’s copies are on display, namely TheLast Supper and St. Peter Freed by the Angel. Still in Casalmaggiore, it is possible to visit the Giuseppe Bottoli School of Drawing, whose gipsoteca preserves antique pieces from Diotti’s private gipsoteca, and again the Palazzo Favagrossa in which the painter frescoed the Toeletta di Venere in 1819, and the Palazzo Comunale, which preserves in the Sala Consiliare the enormous canvas depicting the Oath of Pontida, one of his last masterpieces.

If you continue to nearby Cremona, you can visit the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta (which preserves a cycle of frescoes by Diotti located on the sides of the presbytery, with a Christological and Marian theme, created between 1830 and 1834), Palazzo Mina-Bolzesi with a cycle of frescoes with a mythological theme that allowed him to experiment and practice the technique of fresco painting (until then he made his works on walls using tempera) and whose completion took thirteen years, and of course the Museo Civico Ala Ponzone, which preserves the highest number of the artist’s works, many of which are nevertheless on display in Casalmaggiore. In Bergamo, on the other hand, it is possible to go to the Accademia Carrara, in which Diotti served as a painting teacher and which he then directed for more than 30 years; the Colleoni Chapel, in which there is the oval depicting Tobias restoring sight to his father from 1827; and the Basilica of San Martino Vescovo in Alzano Lombardo, which preserves in the Chapel of the Rosary the painting with Isaac blessing Jacob from 1836. Other works by the painter can be seen in Iseo and Rudiano in the province of Brescia; Lovere, Ranica, and Stezzano in the province of Bergamo; and Soresina and Rivarolo del Re in the province of Cremona.

The retrospective Giuseppe Diotti. A protagonist of the 19th century in Lombardy is set up in a 19th-century palace that the artist bought and renovated in the village in the Cremona area that gave him his birth and death: although he spent his life between Parma, Rome and Bergamo, the painter returned in the last years of his existence to Casalmaggiore where, having settled in the aforementioned palace, now home to the Diotti Museum, he created his last works, namely the Petrobelli Altarpiece, on display for the first time at the exhibition, and the unfinished Oath of Pontida, which was not completed due to his death in 1846. A house-museum inaugurated ten years ago now pays homage with great pride to the artist who spent the last years of his life within its walls, drawing, painting and designing great masterpieces that will forever remain testimonies of his artistic work.

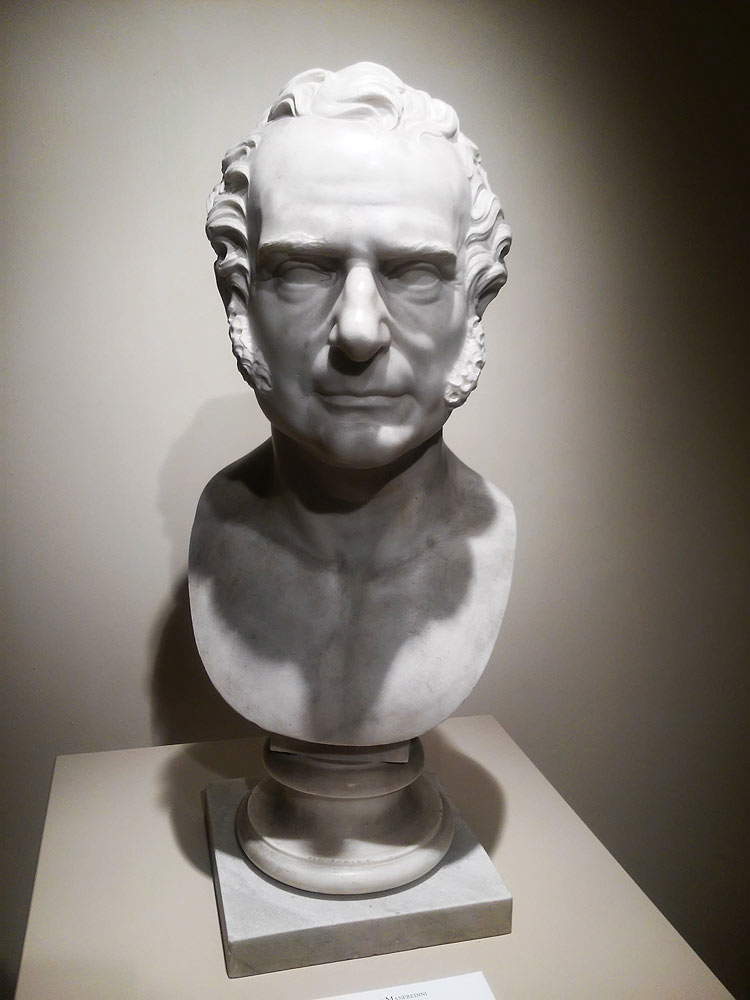

And it is precisely with tributes that the exhibition in question begins: we find here the marble bust made by Gaetano Manfredini in 1837, portraits made with the dellincisione technique and circulated among his friends, and the very special Carme, which some young fellow citizens dedicated to him on the occasion of his return to Casalmaggiore, printed on an embroidered silk handkerchief dating back to 1840. Also on display here is the design of the facade of Palazzo Diotti entrusted to architect Fermo Zuccari.

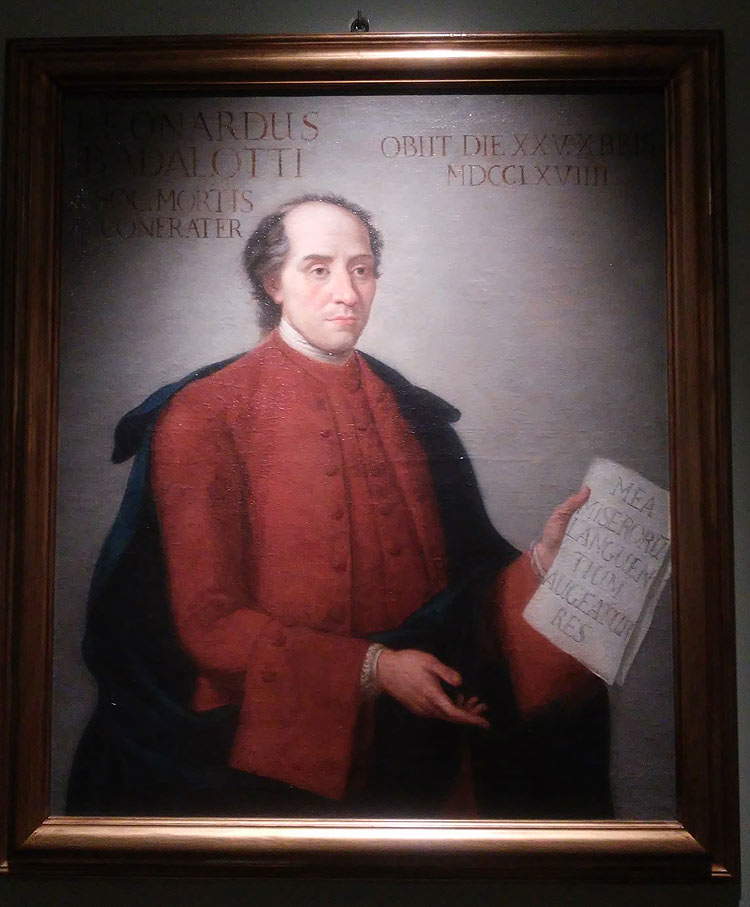

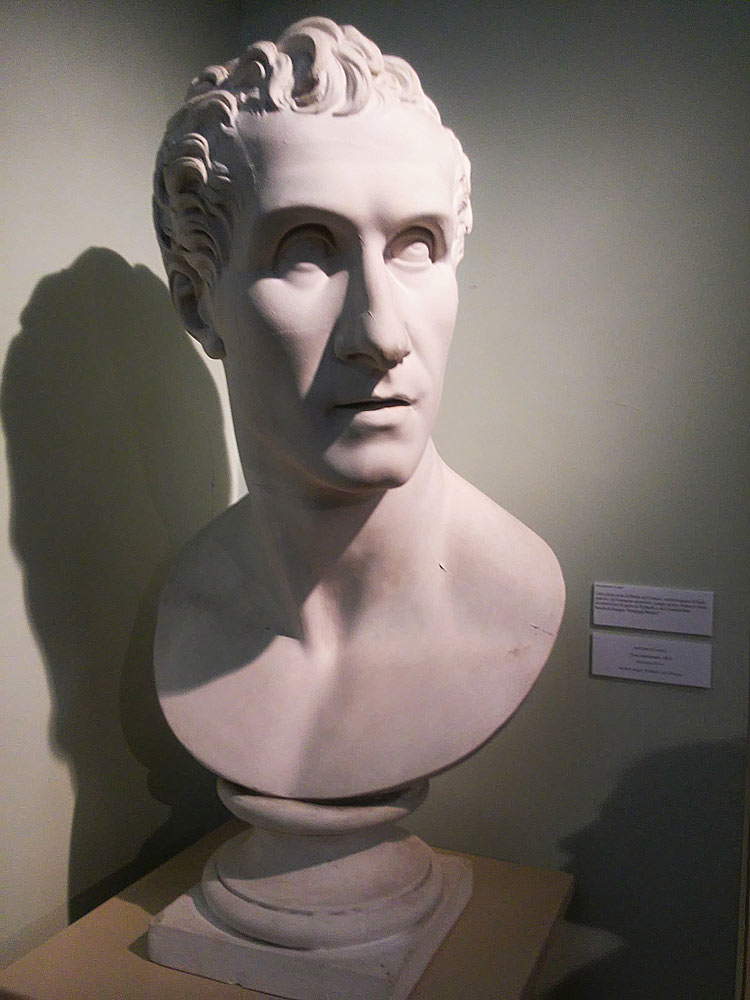

Giuseppe Diotti had a fully academic education, as he attended from 1790 to 1794 the School of Drawing, which was founded in 1768 in Casalmaggiore by Francesco Antonio Chiozzi (whose four fine paintings depicting Joshua, Moses, David and Aaron and the portrait of Leonardo Badalotti are on display), and later the Academy of Fine Arts in Parma. The occupation of the Napoleonic army forced him to interrupt his studies in 1796 and to continue practicing by making copies of ancient paintings: this led him to get closer to 16th-17th-century luminism, for which he made copies from works by Malosso, such as those on display. These are, as anticipated, theLast Supper, which Diotti saw in the Cathedral of Santo Stefano in Casalmaggiore, and St. Peter freed by the angel. The next room is devoted to the years of the Artistic Retirement (1805-1809) that Diotti spent in Rome, guided at a distance by Giuseppe Bossi, an exponent of Milanese neoclassicism, who is present in the exhibition with a copy of the Arm of Justice from the Hall of Constantine, and under the protection of Antonio Canova, whose Self-Portrait Head is exhibited. Some drawings and paintings that the artist sent from Rome to the Brera Academy to account for his progress also stand out. These include Moses presenting the tables of the law (1808), two heads from Raphael’s Dispute (1805), and the wonderful canvas depicting theAdoration of the Shepherds (1809). The latter painting is refined, delicate and ecstatic: the Infant Jesus emanates his own light with an extraordinary whiteness that illuminates the faces and figures of the characters. To the right of the Child, the adoring Madonna on her knees with clasped hands has a sweet and candid face; behind her, Saint Joseph is seated and attends the scene holding his hands intertwined in a singular pose; on the left, a group of shepherds kneeling or in the act of genuflecting adore the Child, and in a privileged position with respect to Jesus, a shepherd holds a docile lamb in his arms and a shepherdess is depicted in the act of offering a dove to the little parishioner. The theme of this work would be taken up in the Petrobelli Altarpiece, considered the final work of the Casalasco artist.

|

| Gaetano Manfredini, Portrait of Giuseppe Diotti (1837; white Carrara marble; Casalmaggiore, Diotti Museum) |

|

| Francesco Chiozzi, Portrait of Leonardo Badalotti (1775; oil on canvas; Casalmaggiore, Deposito Fondazione Conte Busi Onlus) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Head Self-Portrait (19th century; plaster cast; Casalmaggiore, “Giuseppe Bottoli” School of Drawing) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Last Supper, copy from Malosso (1802, oil on canvas; Casalmaggiore, Parish Church of Santo Stefano) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Moses Presents the Tables of the Law (1808, oil on canvas, 162 x 116 cm; Casalmaggiore, Diotti Museum, deposit of the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Adoration of the Shepherds (1809; oil on canvas, 174 x 225 cm; Museo Diotti, depository of the Brera Academy of Fine Arts) |

Trained, as mentioned, in academia, Diotti gave considerable importance to drawing in the creation of his works, so much so that drawing became his main method of work, even in teaching at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo. Moreover, the artist’s direction for over thirty years led the Carrara Academy to form a school of painting that, in terms of teaching method and the training of talented artists, had nothing to envy the Brera Academy (artists such as Enrico Scuri, Francesco Coghetti, Giovanni Carnovali and Giacomo Trécourt were his students).

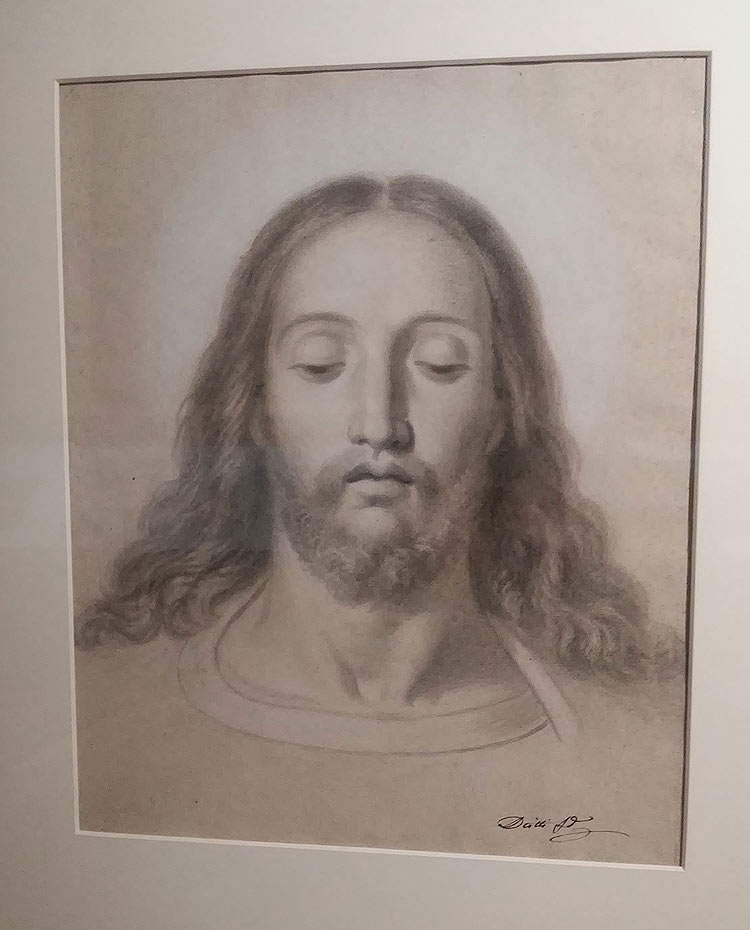

Starting with initial sketches and then moving on to overall or partial drawings, such as anatomical details, draperies, and whole figures, Diotti made full-scale preparatory cartoons for frescoes and large altarpieces. Such as the large cartoon of the fresco of the Delivery of the Keys to St. Peter for the presbytery of Cremona Cathedral, a work that visitors have the opportunity to view in the exhibition. Also placed side by side are the various studies related to the latter, such as the drapery for Saint Peter the Penitent, and those for theAdoration of the Magi in the parish church of Rudiano and the altarpiece in the church of Santo Stefano in Casalmaggiore depicting the Virgin and Child between Saint John the Baptist and Saint Stephen. Also notable is a Head of Christ made in 1833.

A central section of the exhibition is dedicated to Diotti the art collector, a still little-known aspect of Diotti’s activity: in the largest room of the Diotti Museum, where the painter gathered his collection of paintings and art objects formed during his years in Bergamo, later dispersed by his heirs, his collection of prints has been ideally reconstructed.

|

| The room with the large cartoon of the Delivery of the Keys to St. Peter |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Jesus Delivering the Keys to St. Peter, cartoon for the fresco in the presbytery of Cremona Cathedral (1834; charcoal, sfumino and white lead on canvas paper, 247 x 436 cm; Casalmaggiore, Diotti Museum, Bergamo Carrara Academy Deposit) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Head of Christ (1833; pencil, charcoal and sfumino on ivory paper; Brescia, Musei Civici d’Arte e Storia, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

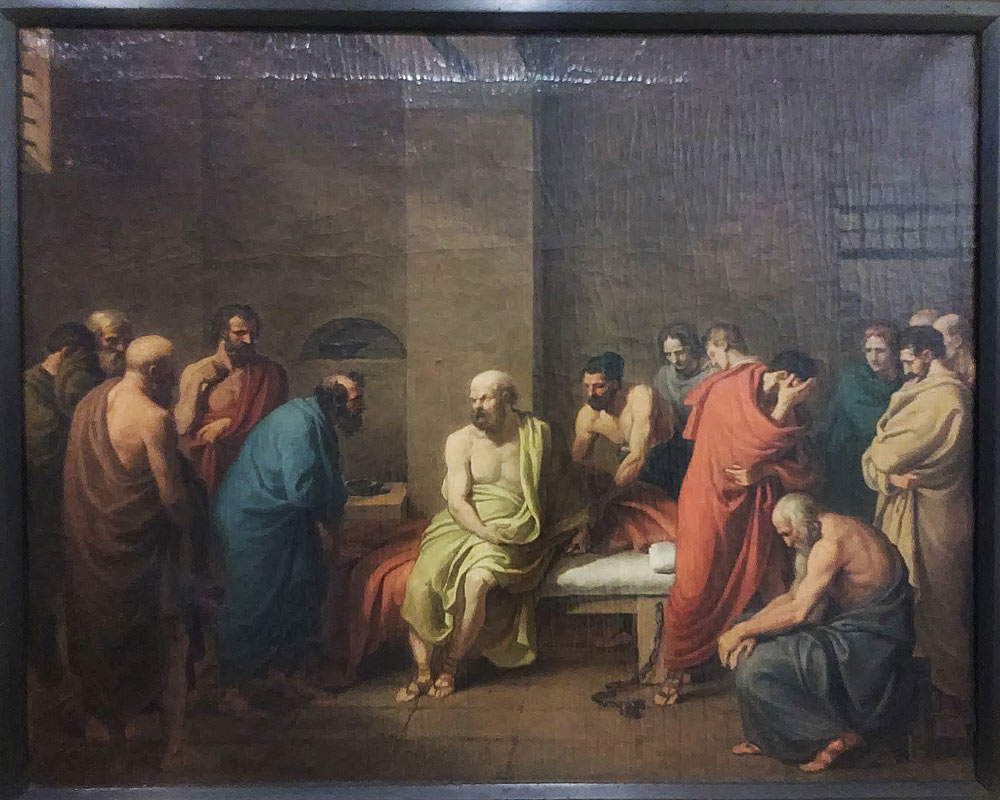

The thematic exhibition continues with the theme of Socrates, a subject addressed during the Artistic Retirement in Rome: on display is a painting from 1809 depicting the Death of Socrates, now in the Ala Ponzone Civic Museum in Cremona. The scene captures the moment when the philosopher, in his prison cell, awaits death after drinking the hemlock, while his friends and disciples despair around him; the vessel with which he was administered the poison is visible leaning to the philosopher’s right. This theme harks back to the spontaneous encounters of artists outside academia aimed at dialogue about thoughts, that is, about how to depict a literary subject. It was precisely on these occasions that the neoclassical workshop developed in which the Casalasco artist participated and was part of.

Relative to sacred painting, we note that Diotti made an innovation in its representation: he freed it from the allegorical patina to be inspired by the classical manner in expressing moral and educational principles. In addition, in sacred depictions he gave significant importance to light, especially in nocturnes: light becomes in most cases a manifestation of the divine, as can be seen in theAdoration of the Shepherds mentioned earlier, as well as in the Nativity of Jesus Christ with Adoring Shepherds the so-called Petrobelli Altarpiece made between 1842 and 1845. Both show the same setting: in the part on the right the Madonna and St. Joseph with two little angels above, in the part on the left the shepherds in adoration, in the center a white light floods the Infant Jesus, who almost appears undefined in his straw bed. Note this device of the theophany of light also in the Beheading of St. John the Baptist (1823-24). Among the drawings and paintings with a sacred theme we admire the beautiful Rebecca (1810), Moses and the Bronze Serpent (c. 1809), the sketch for the altarpiece of the church of Santo Stefano in Casalmaggiore depicting the Virgin and Child between Saint John the Baptist and Saint Stephen (1814), two studies for Saint John the Baptist, and the Kiss of Judas (1839-40), in which only the busts of Christ and Judas are depicted.

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Death of Socrates (1837; oil on canvas; Casalmaggiore, Diotti Museum) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, sketch for the Stezzano altarpiece (1823-24; oil on canvas, 51.5 x 37 cm; Casalmaggiore, Diotti Museum) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Rebecca (1810; oil on canvas, 46 x 38 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Virgin and Child between Saint John the Baptist and Saint Stephen, sketch for the altarpiece for the church of Santo Stefano in Casalmaggiore (1814; oil on canvas; Private collection) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, The Kiss of Judas (ca. 1840; oil on canvas, 162 x 116 cm; Cremona, Bishop’s Seminary, Berenziano Museum) |

Other themes dear to Diotti were those of Count Ugolino in the tower and Antigone, taken from literature. The first, narrated in Canto XXXIII of Dante’s Inferno, is truly famous: Count Ugolino della Gherardesca has been imprisoned in the tower of the Muda for months now with his four sons; the certainty of death comes the moment they hear the access door to the tower being nailed shut. Ugolino is petrified with grief at the tragic end he and his sons will meet, while at a later moment he bites off both of his hands in a gesture of rage: one of his sons, similarly exhausted, believes that his father behaves this way out of hunger, and in one of the most tragic passages of the tale he offers himself to him for food. The affair ends with the death first of the sons and later of Ugolino from starvation (Poscia, più che ’l dolor, poté ’l digiuno: a verse that has also been interpreted, wrongly, as a description of the implausible act of cannibalism of a hunger-won Ugolino who would accept his sons’ macabre offer by feeding on their corpses). The works on display in the exhibition represent in various versions the two moments of despair and rage narrated in the Canto: Ugolino petrified at the thought of the tragic death of his sons and himself, while his sons are already exhausted (one on the right appears unconscious and is supported by a brother) and Ugolino as he bites his hands, with a son offering himself as a meal. We see versions of the theme made by Diotti in 1831-32, and 1836-37, but there are also depictions by Reynolds, Palagi, Doré, and a small painting by Pasquale Massacra.

The theme of Antigone is addressed in the exhibition with a large canvas from 1845 depicting Antigone condemned to death by Creon. The beautiful Antigone was sentenced to death by Creon, king of Thebes, because she was determined to give honorable burial to her brother Polynices, who died in a duel for possession of the throne against Eteocles and was considered a traitor. The Dioptic painting depicts the moment when Antigone and her sister are brought before Creon and, having found them both guilty, he orders their imprisonment. The painting is presented with extraordinary classicist refinement and fine painting technique.Diotti arrived at the present depiction after several studies, drawings and a long conceptual elaboration. Among the studies present, it is also possible to admire the one for Creon’s head.

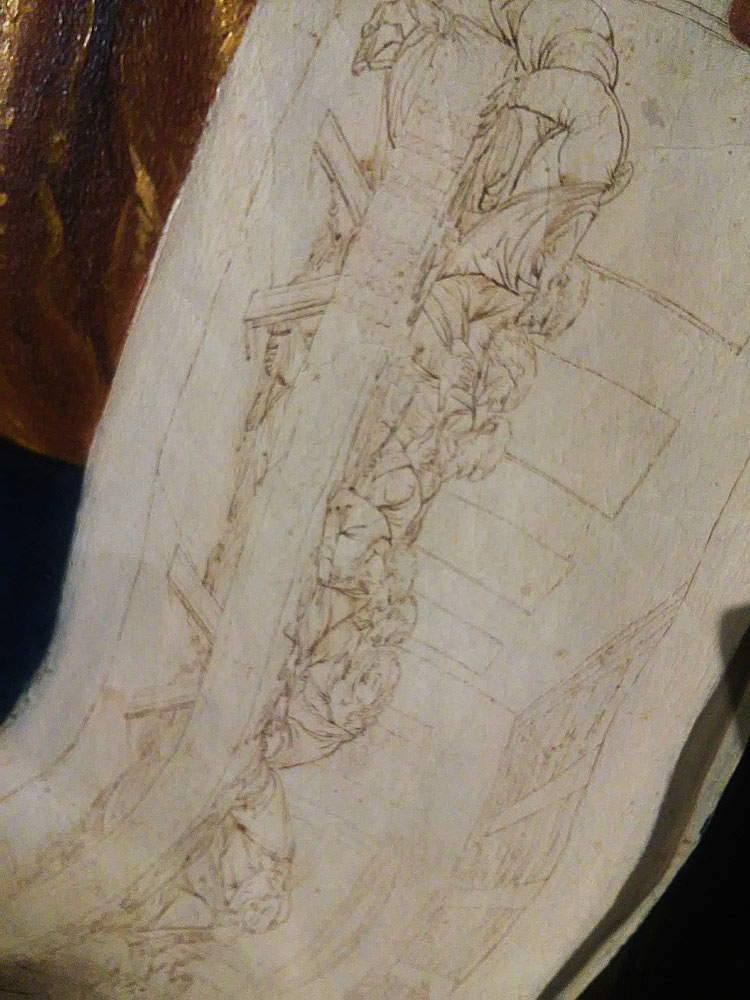

The exhibition continues with the Court of Ludovico il Moro (1823), one of the artist’s most famous works, which belongs to the masterpieces attributable to history painting. This one presents with great pictorial and compositional skill a detailed scene from Lombard history of the 19th century, a time when a prominent figure was Ludovico il Moro at the head of the Milanese court and a time when Leonardo da Vinci’s extraordinary presence in Milan is attested. For the canvas, commissioned by Count Giacomo Mellerio for his villa in Brianza, Diotti enlisted the help of his friends, including Bergamascans Agostino Salvioni and Simone Mayr, who are present in the painting in the guise of historian Bernardino Corio and composer Franchino Gaffurio, as it became necessary to collect numerous iconographic sources relating to the characters’ physiognomies and costumes. The last section of the exhibition is devoted to the Oath of Pontida (at the Diotti Museum the preparatory cartoon, while the large canvas is kept in the Council Chamber of the Municipal Palace of Casalmaggiore) to which the artist devoted the last years of his life. The work, which remained unfinished due to the painter’s untimely death, depicts the moment when representatives of Lombard communes hostile to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa allied themselves by signing the oath in the Benedictine abbey of Pontida on April 7, 1167. The scene is crowded; many characters are depicted, whose features can be likened to Diotti’s pupils and great friends.

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Count Ugolino in the Tower (1831; oil on canvas; Cremona, Museo Civico “Ala Ponzone”) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Count Ugolino in the act of biting his hands, sketch for the Stezzano altarpiece (1836-37; oil on canvas; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Antigone condemned to death by Creon (1845; oil on canvas, 375 x 275 cm; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

|

| Detail of Antigone |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, The Court of Ludovico il Moro (1823; oil on canvas; Lodi, Museo Civico) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, The Court of Ludovico il Moro, detail of the sketch of the Last Supper that Leonardo da Vinci presents to Ludovico il Moro |

|

| Cartoon of the Oath of Pontida |

Retracing this Diotti exhibition itinerary we understand the great versatility of the genius loci of Casalmaggiore: an artist who never forgot and abandoned his academic training, founded on drawing and the study of physiognomies and anatomies, accompanied by a great painting technique with which he gave soul to the canvas. An artist who, however, did not stop at the techniques he learned during his training and the Roman Artistic Boarding School, but tried to innovate the usual iconographies of the time, experimenting and studying. A painter who had nothing to envy to Hayez, his contemporary (1791-1882) considered the leader of historical Romanticism.

Valter Rosa, curator of the exhibition, defines him neither as a tardy neoclassical painter nor as a neo-Davidian out of his time, but rather as a painter perfectly attuned to his own time, tenaciously determined to mark a different path, in his own way alternative and to some extent related as much to historical Romanticism as to the emerging Purism. And even if it is pointed out that this exhibition review is forcibly lacunar and imperfect, in the opinion of the writer this is one of the best composed and conceived exhibitions of this year, intimately linked to its own territory, and we therefore hope that new studies and new discoveries about an artist who unfortunately struggles to attract a large audience today will emerge from it.