by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 10/01/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of Giovanni Frangi's exhibition 'Usodimare,' in La Spezia, CAMeC, through Feb. 19, 2017.

Singing the poetry of the sea. Not an easy task, for which a visceral love for the sea is indispensable, one that also manages to substantiate itself in an intense, passion-filled, continuous, close relationship. Free man, always you will love the sea, wrote Baudelaire: for it is not necessarily the case that the proximity to the sea necessary to grasp its lyricism has to be geographical. Certainly: those who live on the shores of the sea all year round are facilitated, not least by virtue of the fact that, as a phrase by Egisto Malfatti has entered the common imagination of the people of the coast to the point that it has become a kind of popular saying, the children of sailors, wherever they go, will always taste of salt. But with the poetry of the sea is also very familiar a Milanese like Giovanni Frangi (1959), a painter with all evidence cultured and sensitive (one only has to look at his paintings to understand this): a sign that, in the end, proximity to the sea prescinds from place of birth.

The high frequency of the word"proximity" in the first lines of this contribution is due to the fact that it can be an excellent key for those approaching Usodimare, the exhibition of Frangi’s works on the marine theme hosted until February 19, 2017 in the halls of the CaMEC in La Spezia. The sea is just a few dozen meters from the exhibition venue. The air one breathes as one enters the museum is therefore that charged with salt that envelops every city that faces the sea. That can be felt especially towards evening, when it intoxicates you with its scent of iodine and on the wettest days it sticks to you, leaving your skin clinging. Entering CaMEC after taking a stroll along the gulf is the best way to be transported by Giovanni Frangi’s evocative paintings, which take the visitor on a journey through the Mediterranean (but not only) that then, inevitably, ends up bringing him back home, to the shores of that inlet to which Lawrence’s loves, Shelley’s death and Byron’s intemperance earned it the name “poets’ gulf.” Usodimare after Antoniotto Usodimare, the 15th-century Genoese merchant who traveled the world by ship to explore and learn. Frangi’s travels are less adventurous but do not fail in their intent to explore, through a fluid, liquid, almost transparent brushstroke, what lies above and below the surface of the water.

|

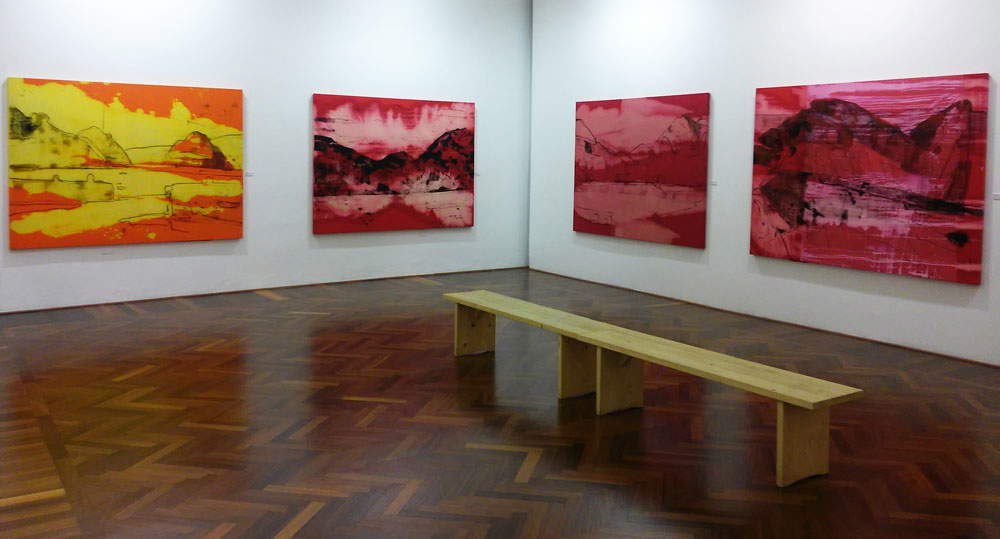

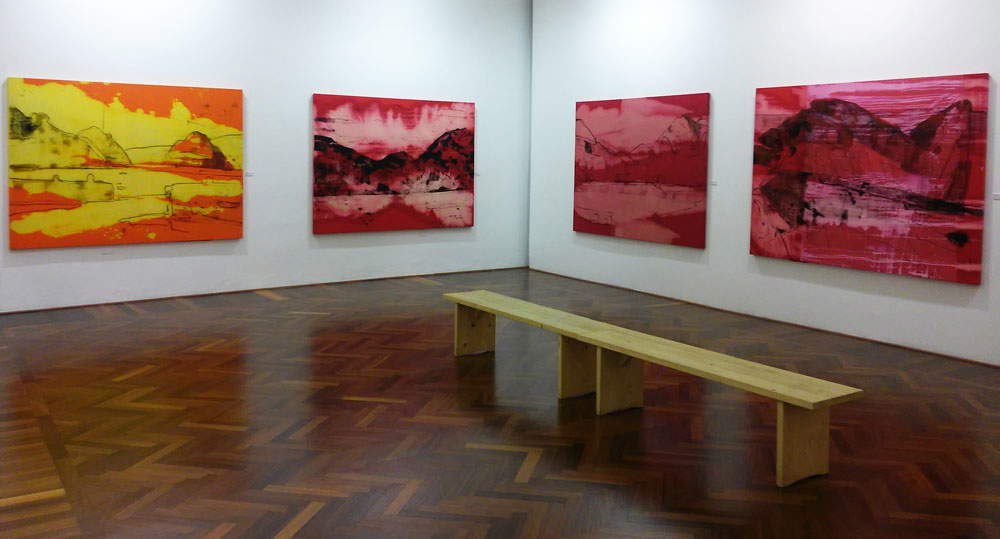

| The last room of the Usodimare exhibition with the Arcipelago cycle created by Giovanni Frangi on the occasion of the exhibition |

|

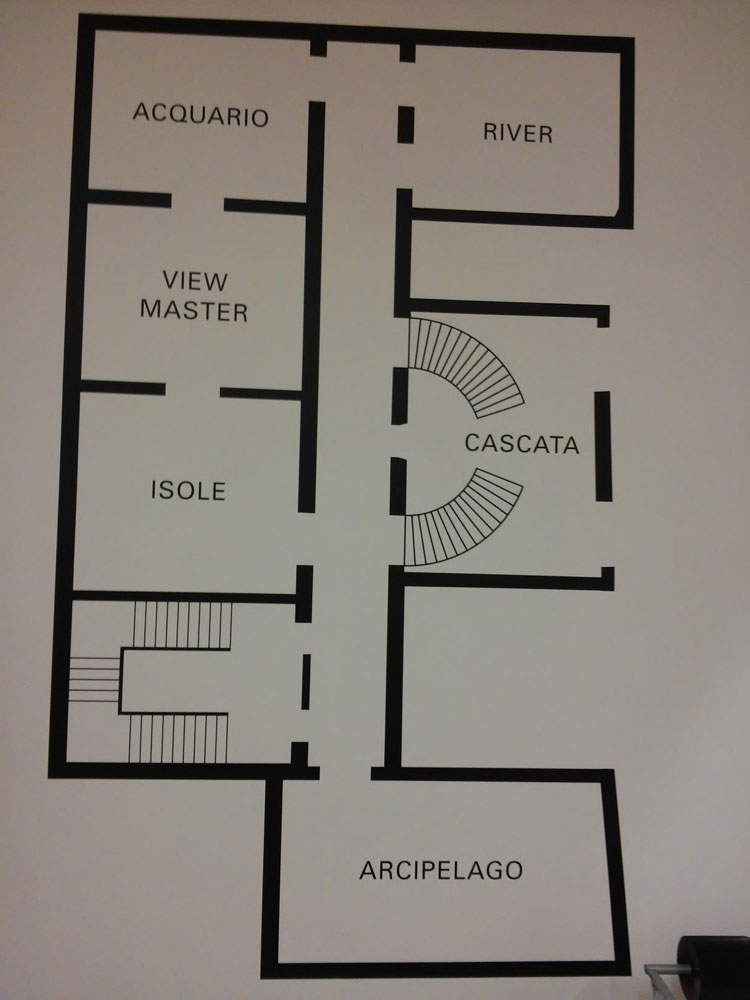

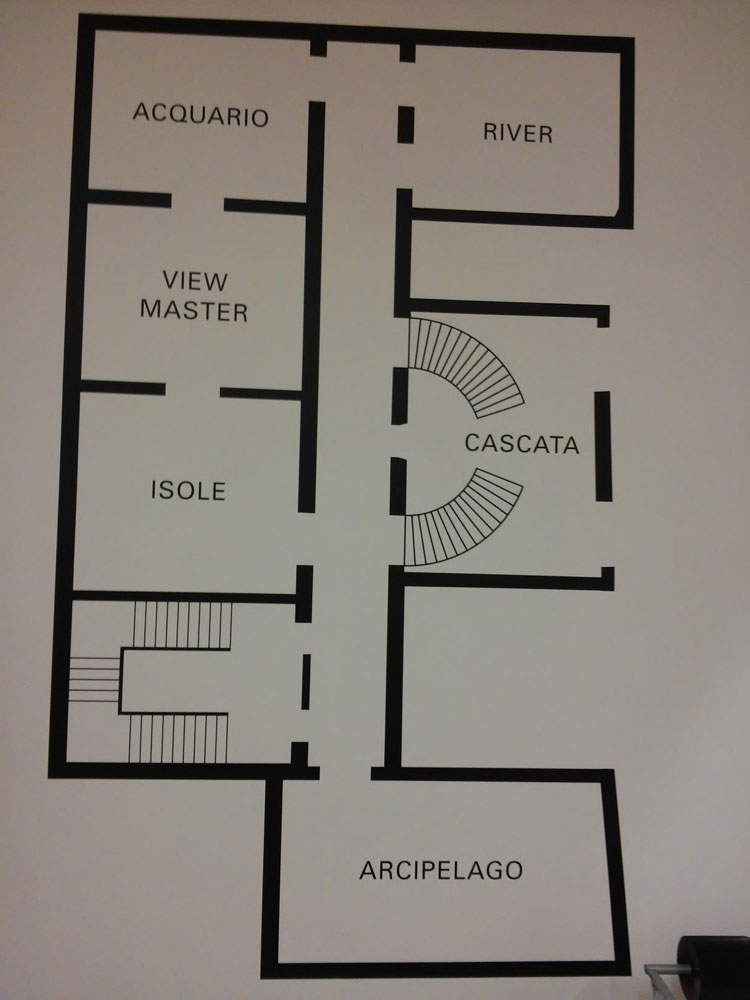

| Map of the exhibition |

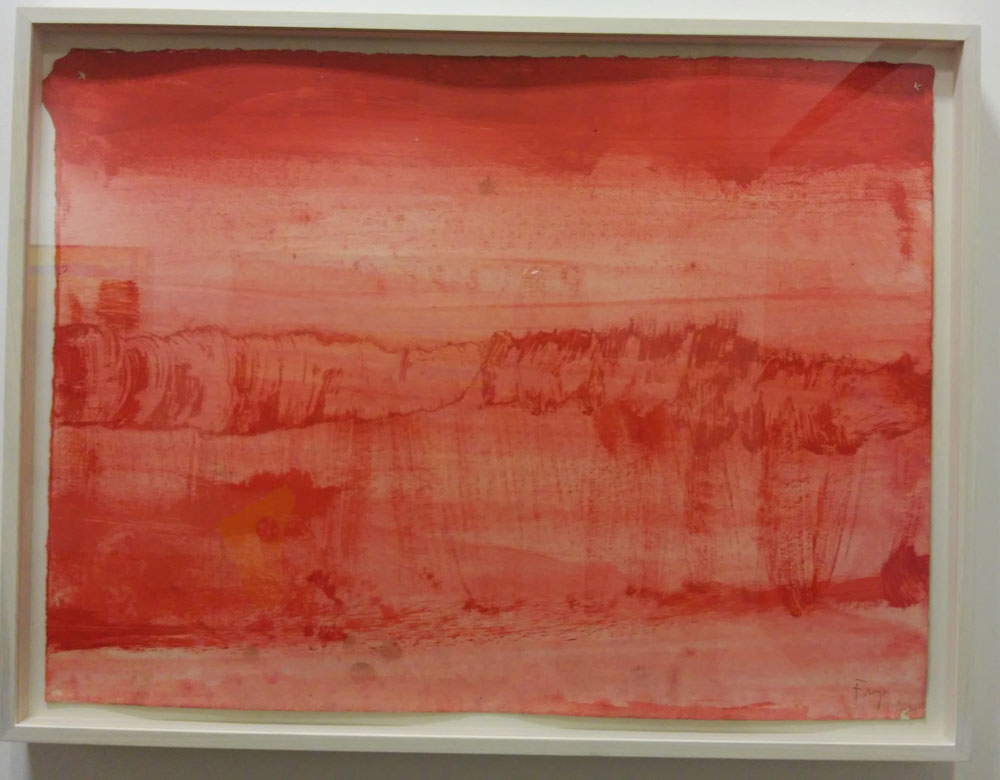

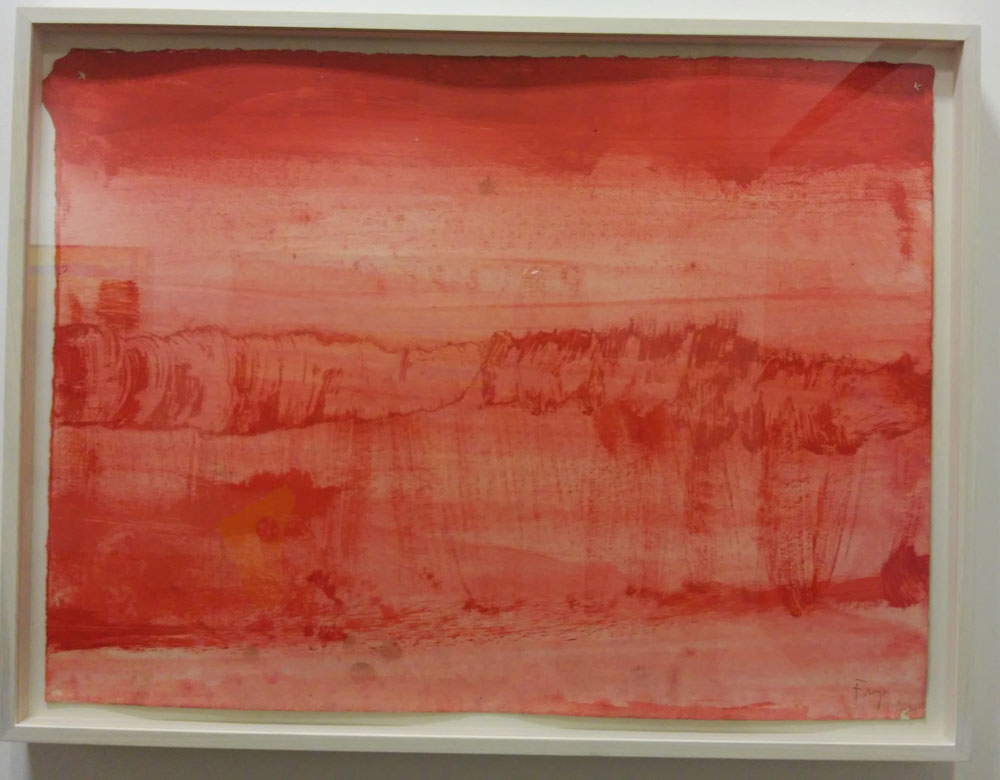

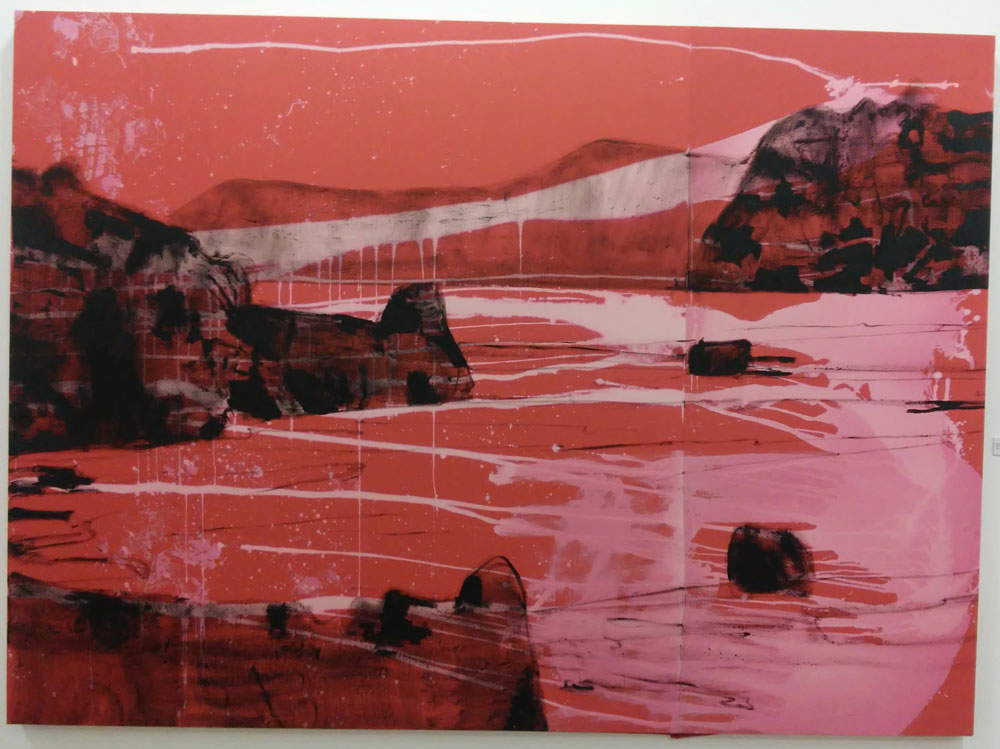

The Islands are visionary views of maritime vistas around the world, which with their violent and unnatural colors (Gauguin, after all, taught us that the artist, if he sees the sea red, must paint it red) envelop the viewer, guided on his journey by the black frames that frame the panorama: open windows on marvelous vistas? Bows of small boats plying the waters taking us to our destination along with someone? Because the island landing, for Giovanni Frangi, is always shared with a person: we arrive in Samos, Greece, with Mara, watching together with her the reddish light of the sun flooding the waters of the Aegean transforming it into a kind of colorful tropical sea. The waters of Cuba, on the other hand, inspire a playful reminiscence in the company of Michi, who takes the form of large Russian Cubofuturist letters that are neatly arranged along the lower edge of the painting. The undertow, on the other hand, resounds in Essaouira: a Moroccan beach on which the waves break, veiled in a vermilion red that divides the sea from our thoughts but at the same time brings it closer to our souls, because the red becomes the screen through which the painter contemplates (and allows us to contemplate) the waves that are breaking on the shore, making us participants in his reflection. Indeed, it should be emphasized that, for Frangi, the sea is neither the exclusive Pérez-Reverte-style sea, which only those who deserve to talk about and those who are up to it can talk about, nor the noisy and crowded summer comedy sea. Frangi’s is a lyrical, meditative sea, made to be seen, breathed and listened to in silence, perhaps in the company of someone you love, to the notes of equally meditative artists: a blues by Buddy Guy, or a jazz by Chet Baker, for example.

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Mara in Samos (2004; oil on canvas) |

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Michi in Cuba (2005; oil on canvas) |

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Essaouira (2002; Primal and pigments on paper) |

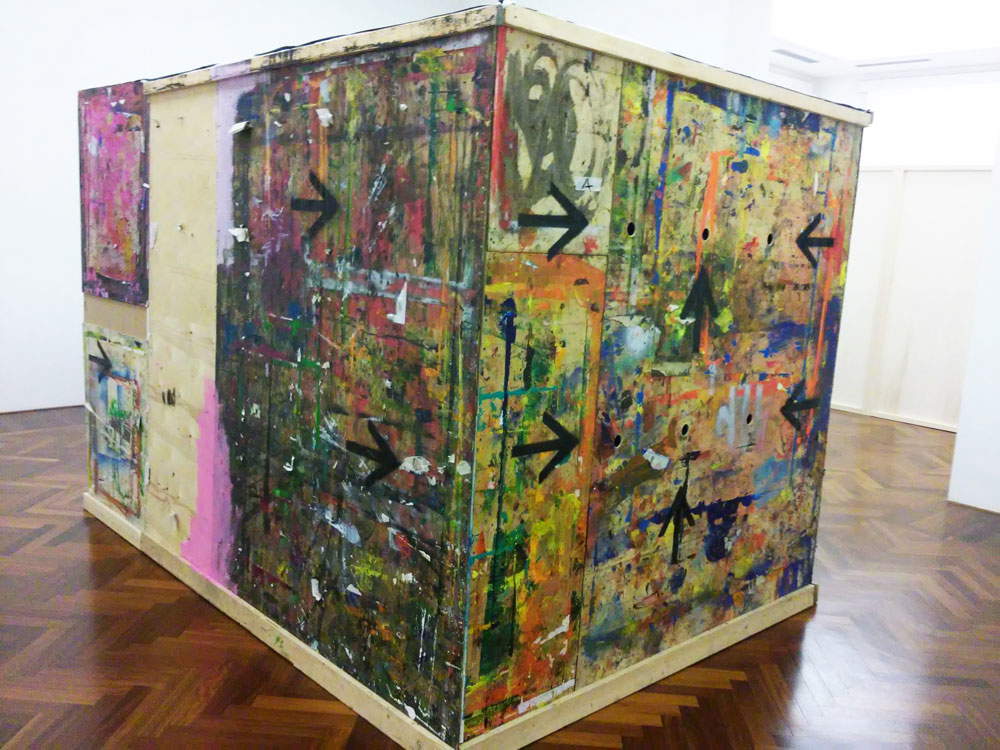

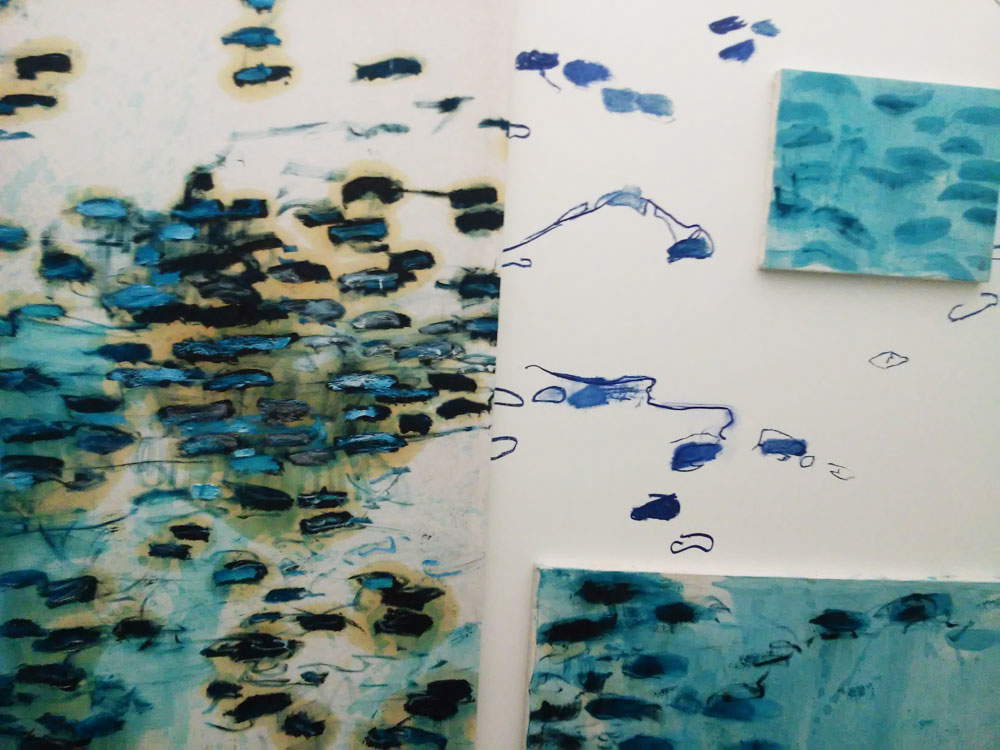

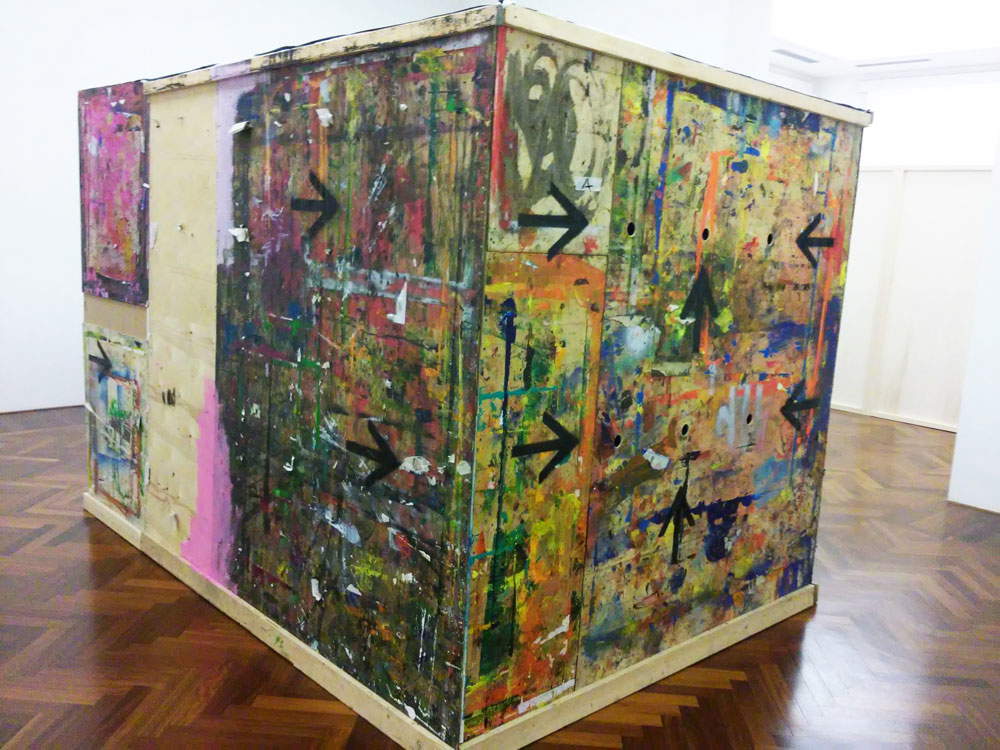

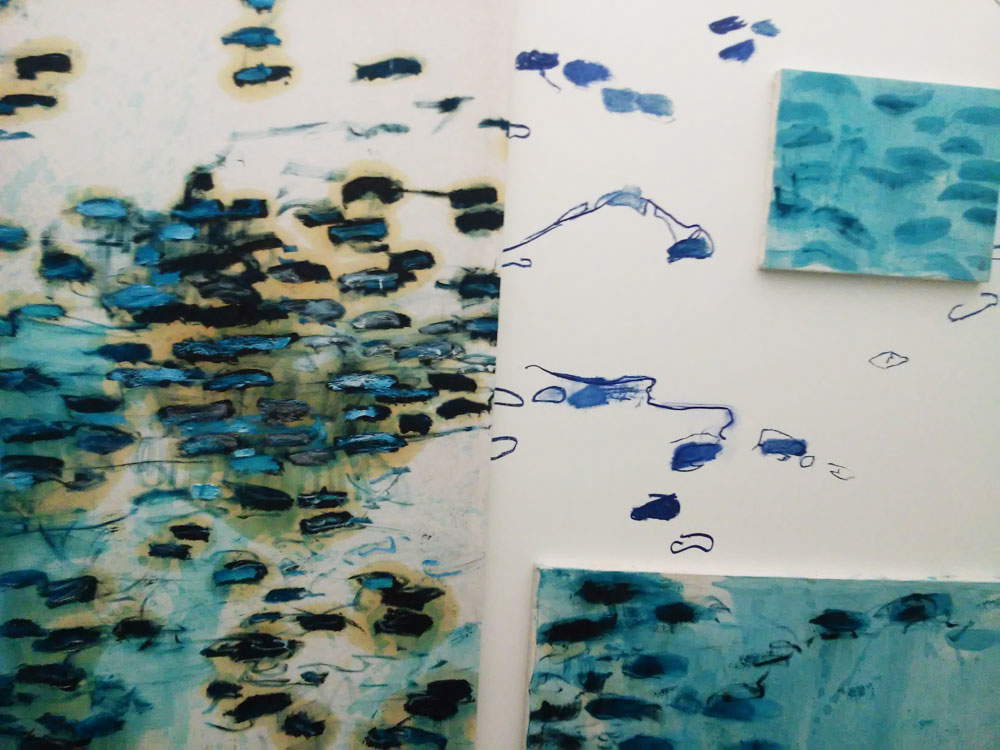

Frangi’s poetry obviously does not stop at the ripples of the surface but also goes so far as to investigate the seabed. The impressions of the islands, those views that recall equally the watercolors of Degas (perhaps the least known productions of his career, but probably also the most emotionally intense) and the swirls of Turner, an artist who comes to mind when our gaze is lost beyond the horizon of Frangi’s paintings, give way to the childlike submerged epiphany of View-Master, an installation conceived like the toy of the same name from the 1930s, a kind of binoculars through which to lose oneself in fantastic visions. It is a huge plywood box, on which the artist has made a few, skimpy parallel holes that allow us to peek inside. There appears to us a world of reefs, seaweed, jellyfish, creatures swimming on the dark, impenetrable bottom of a seabed of which we cannot be a part, but can only investigate as outside observers. Radically opposite, however, is the approach to which Wabi-Sabi’s aquarium calls us: the box, this time, is open, and we enter it, begin to swim in this crystal-clear sea along with myriads of little fish that gathered in festive shoals accompany us, marking with their presence and movement the cardinal points of the whole. Thoughts here can stay out of the box for a while, because Wabi-Sabi is a hymn to lightness, to total emotional involvement: we ourselves become part of the work. A hymn to lightness that is, in fact, profound and pregnant with meaning, as the title of the work leads us to think: “wabi-sabi” is a Japanese Weltanschauung founded on the assumption that everything, in this way, is transitory and, consequently, there is nothing that is destined to remain. We are part of a nature that exists at a given moment but then will be no more: it is we observers-spectators-swimmers, then, who are the metaphor at the center of the work, from the moment we enter this wonderful aquarium to the moment we leave behind the enveloping flickers of the underwater world that Frangi has painted with his usual elegance. A reflection on the relationship between man and nature, a constant in Giovanni Frangi’s art (as the timely captions accompanying the exhibition rooms let us know), on which we are thus called upon to intervene in the first person.

|

| Giovanni Frangi, View-Master, the seabed (2006-2016; foam rubber, pigments, primal, spray, paper) |

|

| Detail of View-Master |

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Wabi-Sabi (2010; oil on canvas) |

|

| Detail of Wabi-Sabi |

|

| The Fish of Wabi-Sabi |

From meditation cloaked in lightness we return to contemplation in the River section: we are still on the water, but we leave the sea for a moment to dive into the rivers. We are particularly surprised by theAdige panels: views by an Impressionist of the 1910s who has Monet’s lesson in mind and offers what appear to us as two intense nocturnes in which the waters of the river that flows between Veneto and Trentino are colored a somber blue furrowed by whitish reflections. The brushstroke is more watery and expansive than ever. Small touches of white in the distance lead us to think that on the river we are sailing, and in the distance we see the lights of a city. Closer to us, oblong shapes, shadows stretching across the water, flickers that almost resemble human figures: are we not alone, then, in this sailing of ours on the Adige?

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Adige 1 (2014; oil on canvas) |

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Adige 2 (2014; oil on canvas) |

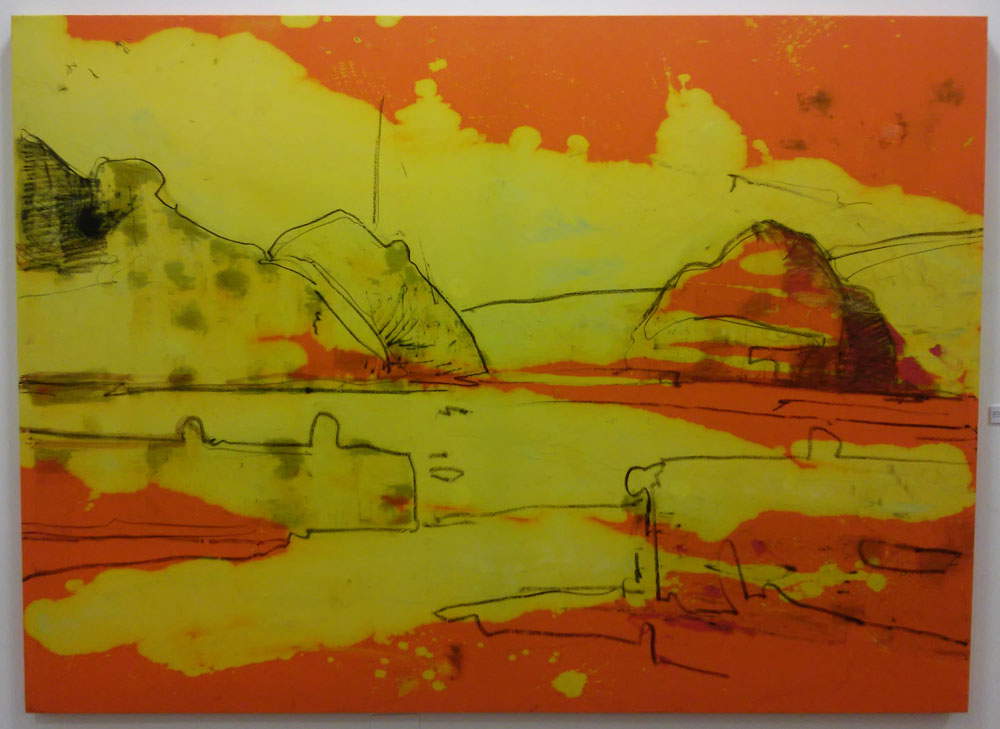

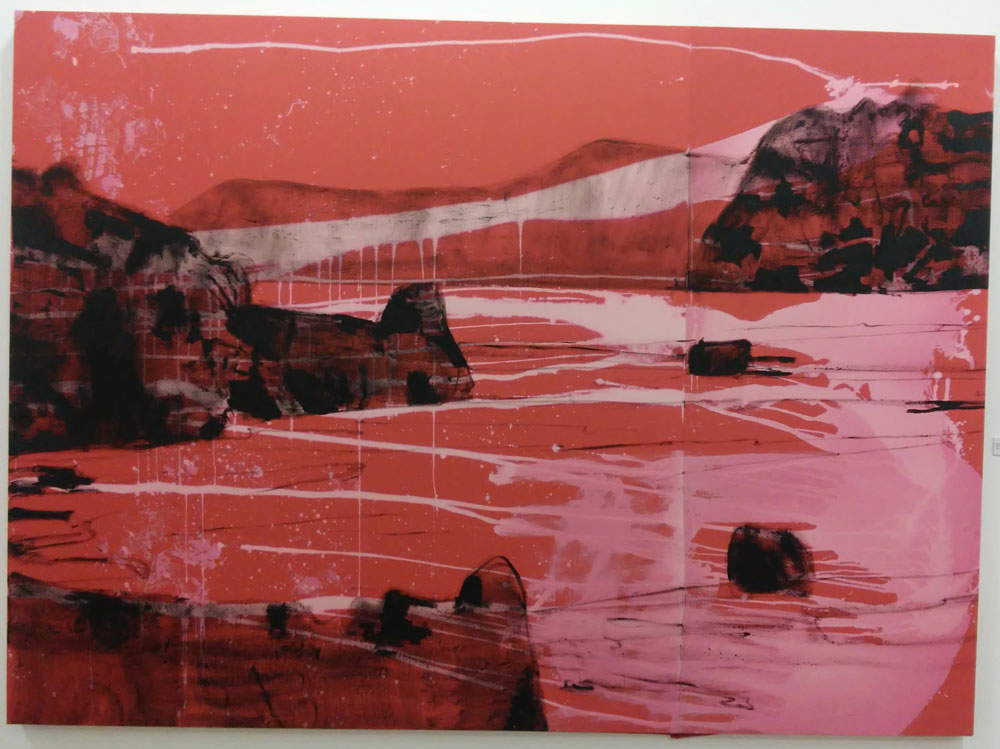

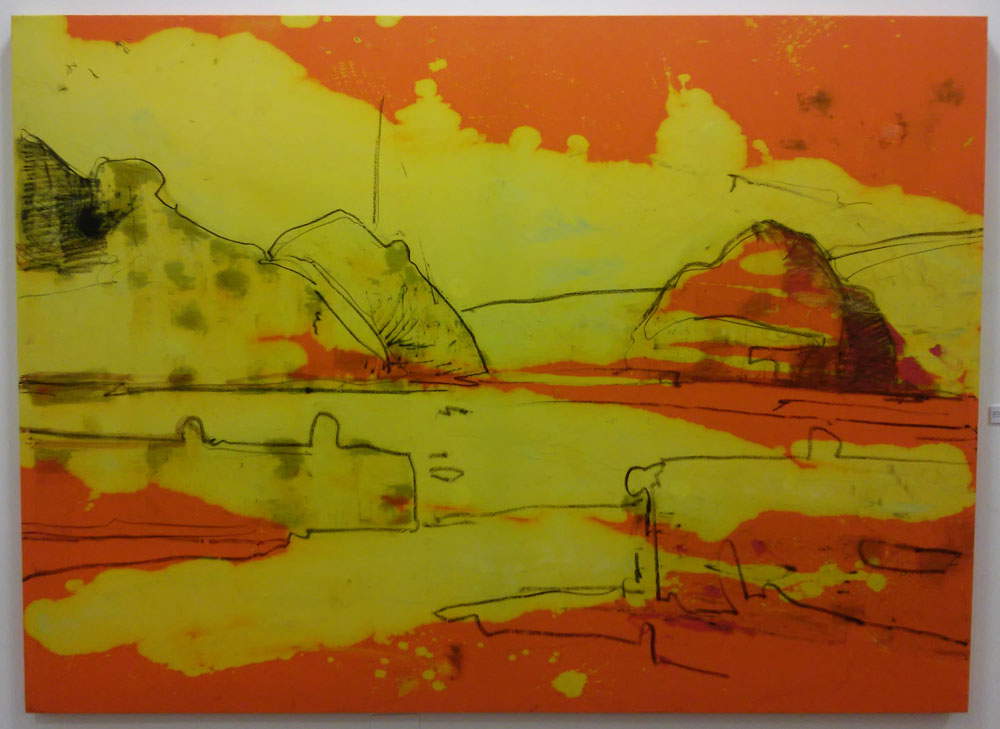

A quick glance at the Waterfall strategically placed around the stairs leading to the lower floor (it is an installation that recreates, precisely, a waterfall: a painting with water flowing vertically, the only case in the entire exhibition, breaking on the foam stones placed at the foot of the painting) guides us toward the inevitable conclusion of our journey. Archipelago is a homecoming: after having traveled the world and immersed ourselves in the depths, Giovanni Frangi takes us back to the shores of the poets’ gulf (though not before making us pass through Greece for a moment), presenting us with a cycle, conceived especially for Usodimare, with some views of Portovenere, Cinque Terre, and Palmaria. Here, an unprecedented black mark, simple but powerful, occasionally sloping into shades that are also liquid, traces the lines of a familiar landscape invested with acid colors that at first glance bring us back to Andy Warhol’s views of Vesuvius. Only there they emphasized an explosion, a drama, a convulsive churning of matter. Here, on the other hand, they describe interior landscapes even before views of the gulf. The viewer, again, stands on the water, and turns his gaze to the land, to those “dark, lustrous rocks of graceful headlands, between one and the other of which appeared, close and inviting, a short inlet of sand or fine gravel.” with their “lush forests that climbed uninterruptedly up the steep hills and gradually closed the view without ever coming to discover the sky or the smallest dwelling,” as another of the great poets who frequented the gulf, Mario Soldati, wrote in one of his memoirs. He was talking about the coast around Lerici, but his description fits well with Frangi’s views looking instead toward Portovenere and Palmaria. The “dark and lustrous rocks” with their little beaches close to us are our guide, our handhold to cling to, as Marco Meneguzzo, curator of the exhibition, suggests, in order not to drown in the pink casts. And to continue to lose ourselves in the wonder of a nature from which Frangi, for the occasion, seems to have expunged any human trace (as Soldati had done in his memoir), bringing us back to a gulf of poets still far from boisterous tourism and not yet become today’s “container gulf,” according to the nickname invented by Marco Ferrari, a La Spezia writer with a profound knowledge and refined narrator of these places that, despite everything, still remain full of poetry. It is enough to know how to find it and how to grasp it, and Frangi’s invitation is self-evident.

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Waterfall (2005; oil on canvas, foam rubber) |

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Archipelago, Palmaria southwest view (2016; oil on canvas) |

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Archipelago, Clear Dawn (2016; oil on canvas) |

|

| Giovanni Frangi, Archipelago, September (2016; oil on canvas) |

The water of Frangi, one of the most interesting painters on the contemporary Italian scene, flows in a space that lies somewhere between the natural datum and introspection but which hardly lends itself to being enclosed within rigid conventions. Liquid is not only Giovanni Frangi’s paintings, but it is the exhibition itself, which allows the visitor, as already mentioned, to “swim” among the works of the Milanese artist, to choose his own thread, to go back to the beginning and start looking again as if transported by a current flowing inside the halls of CAMeC, an institution among the most up-to-date and, at the same time, among the least taken for granted in Italy when it comes to contemporary art, which deserves the credit for having given life to a dense retrospective, which rereads Frangi’s works of the last fifteen years on the theme ofwater from a unified point of view, presenting them to the public (even to those not necessarily accustomed to contemporary painting) with coherence and surprising communicative ability. A review of high quality, inextricably linked to the territory that hosts it (thus further intelligent), and from which not only the artist’s culture and philosophical reflections shine through, but also, perhaps more trivially, all his love for the sea, to be shared with other lovers of the sea, and not only.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.