by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 19/11/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Genovesino. Nature and Invention in Seventeenth-Century Painting in Cremona', in Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone, from October 6, 2017 to January 6, 2018.

In the autumn of 1647, the quiet existence of the city of Cremona, which had experienced nearly two decades of relative calm after the great Manzoni plague, found itself disturbed by the events of the Franco-Spanish war. Cremona, the most important pro-Spanish city immediately south of Milan, was besieged in October of that year by the Duke of Modena, Francesco I d’Este, commander of the French forces in Italy, who nevertheless underestimated the fierce resistance of the Cremonese. The city in fact had no walls or fortifications: nevertheless, Lorenzo Manini narrates in his Historical Memoirs of the City of Cremona, “shelters were erected, ditches dug, trees felled, villages ruined, and bridges cut across the canal along the road known as the Cerca, so that enemies would not approach [...]. The urban militia took up arms, and was reinforced with several ranks of peasants,” to which were added “the poor and artisans.” The inhabitants, aided also by the heavy rains of that autumn that caused widespread flooding in the countryside, forced the enemies into a truce: the Franco-Modenese thus spent the winter in Casalmaggiore, and tried to attack the city again in the summer of 1648, suffering the ultimate defeat, partly because the Cremonese had spent the winter fortifying the city and were supported by thousands of Spanish soldiers. The besiegers had to content themselves with wreaking havoc on the countryside. Disturbing news was therefore coming from the countryside: the enemies were robbing, harassing and imprisoning the inhabitants, and they were only subjecting the country churches to pillage, stealing the works of art preserved there.

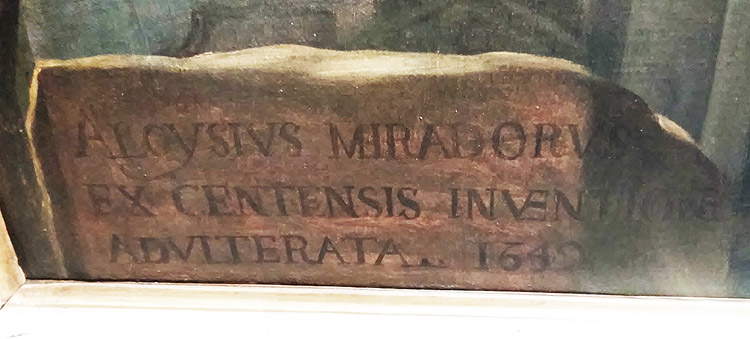

In that same year, the greatest artist active in Cremona, Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino (Genoa?, c. 1605-1610 - Cremona, 1656), painted, for the parish church of San Clemente, the altarpiece depicting the Miracle of Saint John Damascene: the saint had fought vigorously against the iconoclasts of Emperor Leo III, and in response his adversaries had raged against him by cutting off his hand, which in the painting is literally reattached to his arm by the Madonna and the Child Jesus. The painting is one of the protagonists of the major exhibition, the first monographic exhibition ever dedicated to Genovesino, entitled Genovesino. Nature and Invention in Seventeenth-Century Painting in Cremona, which is being held precisely in Cremona, at the Museo Civico “Ala Ponzone”: for Valerio Guazzoni, who together with Francesco Frangi and Marco Tanzi is one of the curators of the important exhibition, the painting that Luigi Miradori executed in 1648 could hold a very high symbolic significance, given the circumstances of the time in which it was made. The plundering to which the Franco-Modenese subjected the countryside around Cremona was certainly not dictated by iconoclastic fervor, but the results appeared quite similar, and it would like to think that the artist wanted to offer the inhabitants of his adopted city a painting in front of which they could gather in order to avert the danger of seeing the city meet the same distressing treatment that the enemies reserved for the rural villages.

|

| The entrance to the Genovesino exhibition at Cremona’s Ala Ponzone Civic Museum |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Miracle of Saint John Damascene (1648; canvas, 207 x 140 cm; Cremona, Santa Maria Maddalena) |

The work comes almost to the end of the exhibition itinerary, but we chose to present it at the opening because it is particularly illustrative of the times in which Genovesino lived (and his art is heavily influenced by the climate of the time), and also because it is an important witness to a close relationship with a city that welcomed him after a not particularly fortunate life: not even thirty years old, Luigi Miradori had lost his wife, Girolama Veronesi, a Genoese like himself, and two children, and had first left Genoa (although we do not know the reasons why), and then Piacenza, a city in which he had not been able to find enough work. The final move to Cremona, however, had a decisive effect: in the Lombard city, the Genovesino achieved the success he deserved. Fame, however, did not come to him in the same way after his demise: soon forgotten, scarcely mentioned by the sources, he was rescued from oblivion only thanks to the work of a great Cremonese, Mina Gregori, who dedicated to the Genovesino, in 1949, her own graduation thesis discussed at the University of Bologna, starting the rediscovery of one of the most versatile artists of the seventeenth century, which continued in 1954 with a new study signed by herself, and then with several contributions born in the wake traced by the fundamental essays of the distinguished scholar. And as much as the Genovesino catalog has been enriched over the decades, and although his works have begun to be shown with insistence in exhibitions devoted to the seventeenth century, a monograph that could provide both scholars and the general public with a complete and up-to-date overview of the artist had hitherto been lacking.

The start of the Cremonese review is decidedly intriguing: not only because the first room presents a number of works that make manifest Genovesino’s ties with his native land (although, given also the obvious Lombard cues, it is as difficult as ever to be able to place them chronologically), but also because the paintings exhibited here constitute an initial critical and historical introduction to the artist. The first work we are confronted with is the Suonatrice di liuto, first recognized as a work by Genovesino by Roberto Longhi in 1951, when the art historian was preparing the celebrated Caravaggio and Caravaggesque exhibition in Milan, an exhibition in which Luigi Miradori’s Suonatrice also had a place. The work, however, had already been known for some time, and the fact that a great scholar such as Wilhelm Suida (who deserves the credit for being the first to mention it) considered it to be the work of a young Caravaggio, should be eloquent indications of the artist’s abilities as well as the quality of this canvas, which induces the viewer to reflect on the transience of life: the young woman devotes herself to worldly pleasures, symbolized as much by the lute as by the jewelry scattered on the table and the sack of coins, but looming over her is the torn sheet of paper and especially the ominous skull located in the upper right corner. A theme, that of vanitas, which will recur, in all its lugubrious visionariness, to consistently punctuate the painter’s production. And besides the iconological datum (reflection on the transience of man was typical of the time) interesting, as with all Genovesino’s paintings, is the stylistic one: obvious are the Caravaggesque references (modeling, atmospheres, lights, drapery), probably mediated by an Orazio Gentileschi known in Genoa, but the links with the hometown could also result from the profile of the suonatrice, which shows more than one debt to the art of Bernardo Strozzi, one of the great names of the Ligurian seventeenth century (however, in the exhibition, it should be emphasized, there are no works by other artists).

Another painting in the same room also has Ligurian overtones: the subject may be the Punishment of Core, Dathan and Abiram, three biblical characters who, as we read in the book of Numbers, rebelled against the authority of Moses and Aaron and were for that reason punished by God (there are, however, some inconsistencies with the religious text). The characters gather around the altar on which Moses had decided to offer, along with Aaron and the three rebels, sacrifices to God: the deity would then choose who was worthy of incensing, reserving punishments for the others. Thus, punctually, we see some of the rebels being sucked from the earth, while the sky is ripped open by God’s lightning bolt that illuminates the night and moves all onlookers to amazement (of particular effect is the passage of the two women who, in the lower right corner, watch in wonderment as this happens). The work is another cornerstone of criticism: assigned to Genovesino in 1939 by Armando Quintavalle after a cue suggested by Longhi, it was then with profusion of analysis by Mina Gregori, who emphasized its dependence on the manner of Gioacchino Assereto, as well as on Lombard naturalism.

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Lute Player (canvas, 138 x 100 cm; Genoa, Strada Nuova Museums, Palazzo Rosso) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Punishment of Core, Dathan and Abiram? (canvas, 71.8 x 117.7 cm; Parma, Galleria Nazionale) |

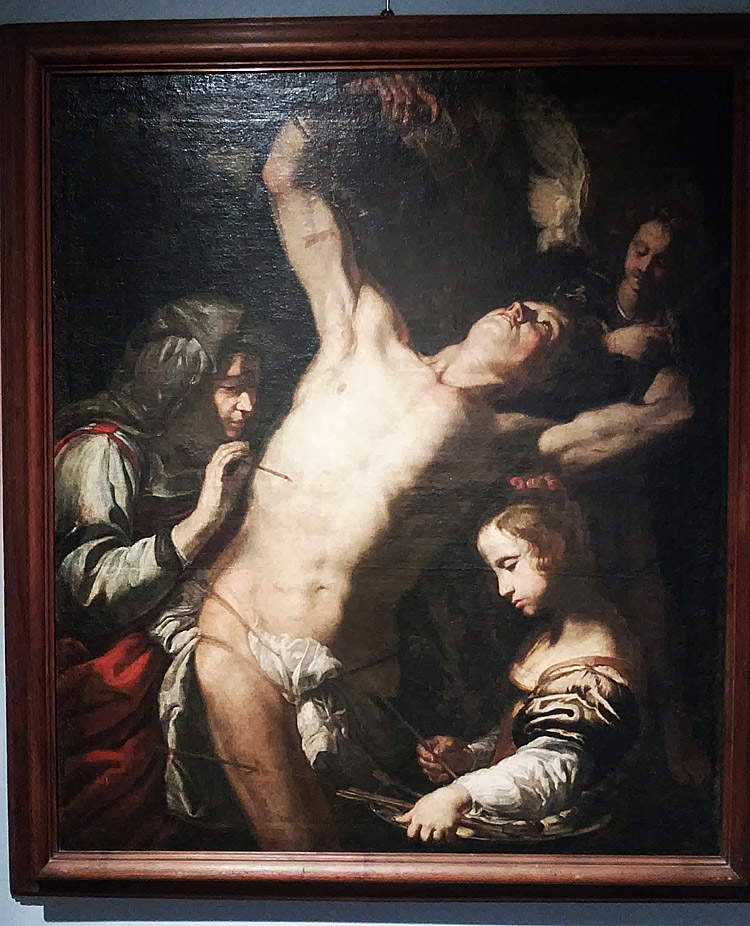

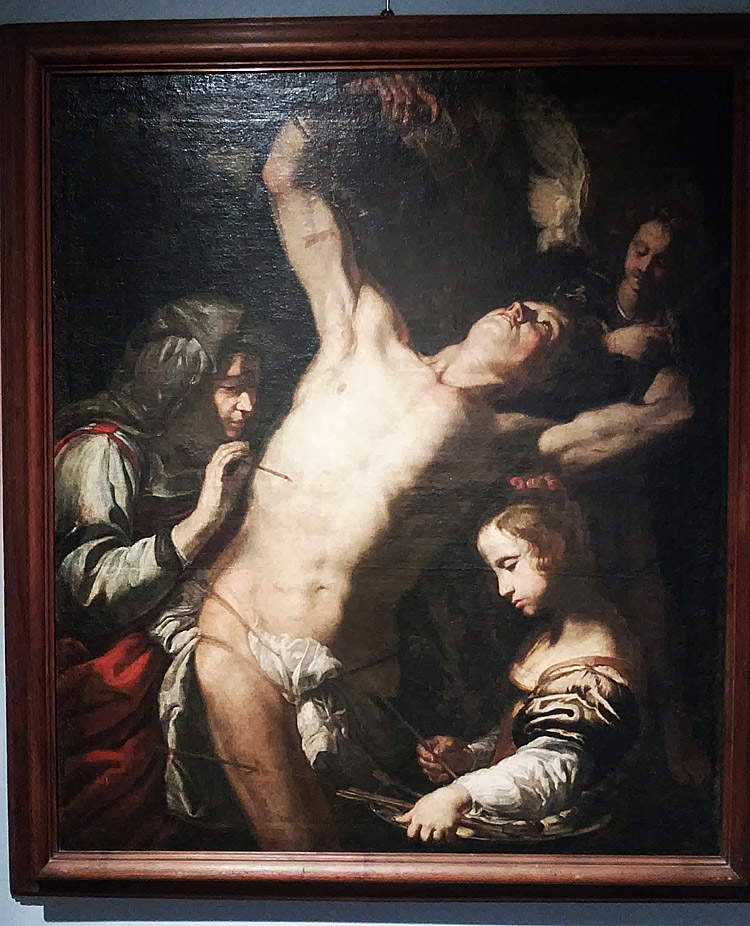

With the next room (a dark and intimate room), we begin to learn about some of the staples of Luigi Miradori’s production. The first of these is a Holy Family, now kept at the Gazzola Institute in Piacenza, signed and dated 1639 (we see the signature and date on the note the artist inserts under the Madonna’s chair): this is the Ligurian painter’s first work that can be dated with certainty. It is a tasty and touching narrative of a family idyll: the baby Jesus takes his first steps in front of the Virgin who, as any mother would do when she sees her child walking for the first time, stretches her hands forward to keep him from falling. Above, a younger-than-usual Saint Joseph leans his hands on his staff and watches the scene smugly. Below, two rabbits, one white and one black, flanked by a pair of pens and an inkwell whose symbolic meaning escapes us, and which constitute a clear homage to the animalist painting that was widespread in seventeenth-century Genoa and which had seen in Sinibaldo Scorza its first prominent representative, later followed and surpassed by Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, better known as il Grechetto. Genoese references would also demonstrate the figures of the Virgin and Child, which resemble the counterparts of Anton van Dyck, an artist known to have sojourned in Genoa in the early seventeenth century. Of a different accent is the decidedly more crowded Adoration of the Magi, with the figures squeezing in to occupy every possible corner of the scene: only one space at the top, the one cluttered by the roof of the hut, remains open. Another painting of uncertain provenance (as are all those seen so far), theAdoration of the Magi is a work that feeds on the contrasts between the humble tone of the Holy Family (note St. Joseph: he looks at the procession, but almost seems to want to stand aside) and the luxury of the procession of the Magi, who arrive complete with page and greyhound. The latter is taken from an engraving by Albrecht Dürer, but Nordic is also the setting of the scene, which derives from a print by Hendrick Goltzius: such works were known to circulate in abundance in the workshops and schools of the most artistically up-to-date cities. And it brings us back again to Genoa a further work of which very little is known: a Saint Sebastian cared for by Irene still of Caravaggesque intonation: the model here is Simon Vouet, who in the Ligurian capital painted, in 1622, a painting of similar subject, now in a private collection, for Giovan Carlo Doria. The figure on the lower right is then again related to Bernardo Strozzi: there may be sufficient clues to indicate in this painting one of the rare works executed by Genovesino in his hometown.

We then move on to a room displaying small-format paintings, which show a style still halfway between Genoa and Lombardy. These are paintings that are difficult to place, but which offer clear evidence of the artist’s versatility: of particular interest is an unpublishedLast Supper, which revisits the Gospel episode “with the inventive originality that Genovesino always brings to bear, even when he has to deal with the most popular themes” (so Francesco Frangi in the catalog): space, therefore, for a devil who emerges from the ground to put chains on Judas the traitor, who still clutches in his hands the bag with the thirty denarii, space for the more than unusual choice of representing thirteen apostles, instead of twelve (Saint Matthias already figures called in place of Judas), space for characters who converse in an obvious state of intoxication (and we shall see how this is not the only case in Genovesino’s production in which the Last Supper is treated as if it were a dinner in a tavern: raw Lombard realism, here treated with Ligurian colors). And again: the remains of the chicken on the plate, an apostle pouring wine on the floor (why, we do not know), St. John falling asleep disheveled on Christ’s arm. Less boisterous, and conversely more meditative, is the panel with the Funerals of the Virgin, a work from the Cremona Civic Museum: possibly part of a predella, it is a somber painting, furrowed by the mournful figures of the candles whose white outlines dart across the dark background, and veiled by the palpable sadness of the apostles, arranged “as if on a stage” around that “blue catafalque of perfect geometric solidity” that stands at the center of a “markedly perspectival compositional layout, dominated by precise, well-scored volumetries” (Beatrice Tanzi in the catalog entry).

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Holy Family (1639; canvas, 182 x 134 cm; Piacenza, Fondazione Istituto Gazzola) |

|

| The Rabbits of the Holy Family |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Adoration of the Magi (canvas, 240 x 178 cm; Parma, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Saint Sebastian being cared for by Irene (canvas, 130 x 111 cm; Genoa, Museo dei Beni Culturali Cappuccini) |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, The Funeral of the Virgin (panel, 35.5 x 92.3 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Last Supper (panel, 27 x 44.5 cm; Private collection) |

The next two rooms introduce us to the most unusual paintings in Genovesino’s production. We begin with an entire room devoted to vanitas, a theme among the most popular among artists in an era of wars, widespread famine, epidemics, and generalized distrust, a theme that constituted the macabre counterbalance to Baroque magniloquence, and a theme that Luigi Miradori, as a man of his time, practiced assiduously, casually, and above all with a wholly personal sensitivity. Genovesino’s memento mori do not have the funereal coldness of their Flemish counterparts, do not arouse revulsion like Jacopo Ligozzi’s horrifying ones, nor do they include moments of action, or aim to move the viewer to awe. His variations on the theme are all marked by a great lightness: next to the macabre always figures a delicate element, which softens the scene achieving, thanks to such a skillful play of contrasts, the result of capturing the viewer by inducing him to dwell on every single detail of the composition. A similar effect is elicited by a work such as the sleeping Cupid leaning against a skull with its mouth wide open, from which, a gruesome detail, a toad emerges (which plays, in a kinder way, the same role that in similar paintings by other artists is played by insects: a symbol, therefore, of corruptibility): the composition might again derive from Goltzius’ engravings, but Miradorian inventiveness succeeds in making it much more suave by securing for our view a plump Cupid with flushed cheeks, asleep, and a vase of flowers (both symbols of goods destined to fade away: love and beauty) that lighten the skull’s gloomy presence. There is no shortage, however, of more terrifying memento mori: the Vanitas of Breno, a recent acquisition in Genovesino’s catalog, is simply and terrifyingly composed of a skull resting on top of a bloody surface and accompanied by a scroll that, in Latin, reads “morieris” (“you will die”).

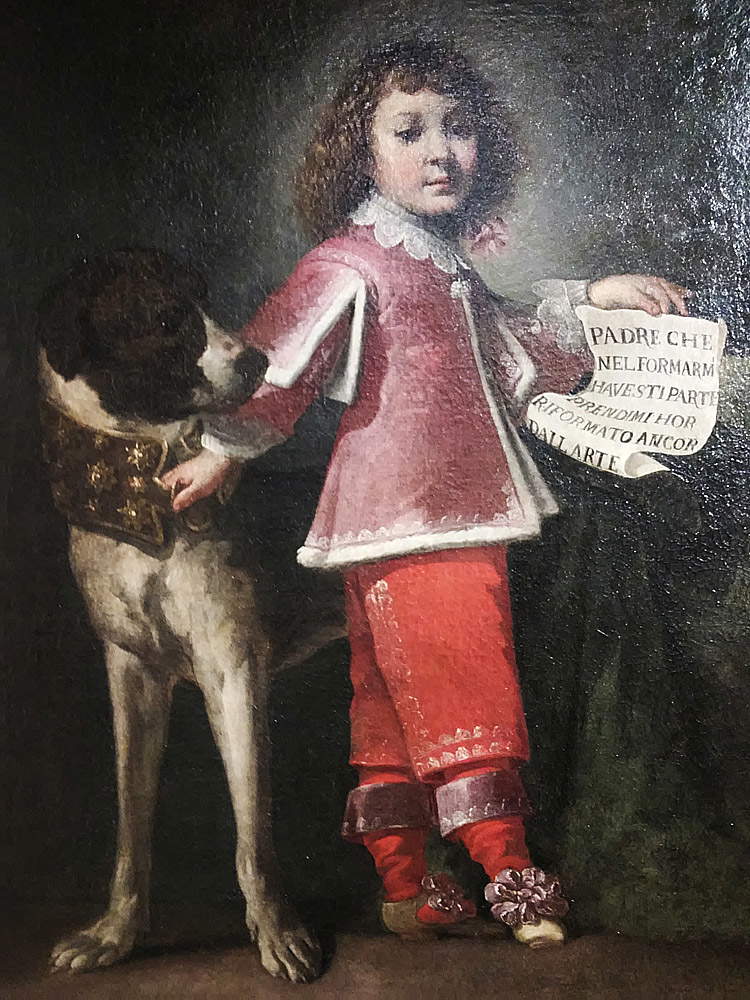

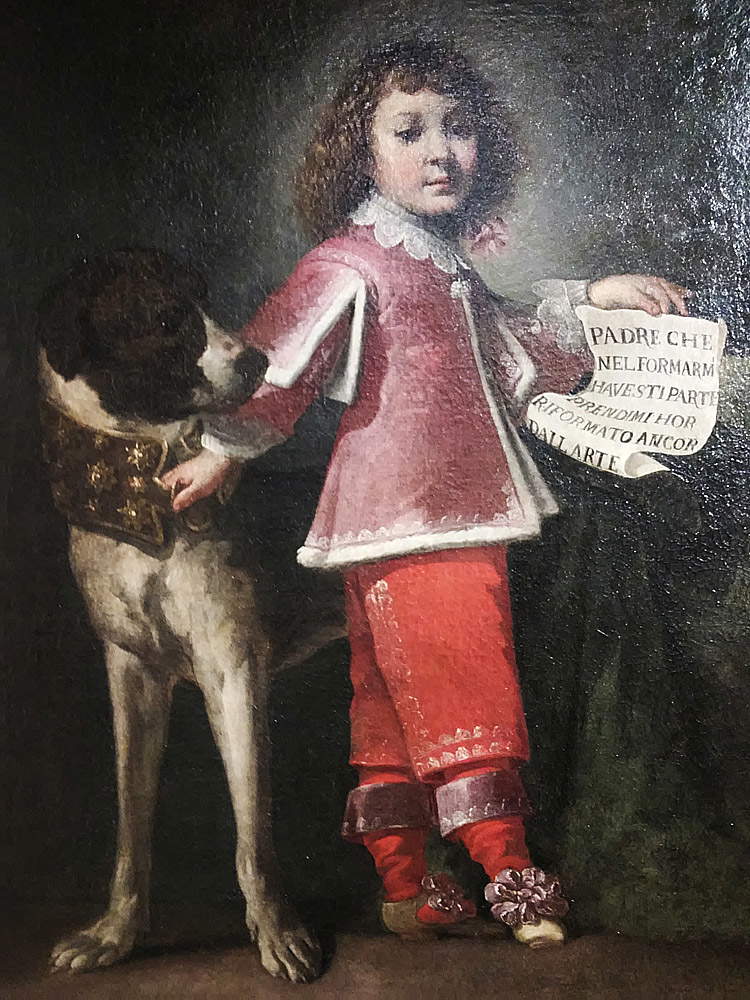

That the Genoese painter had a penchant for unusual themes is shown by several paintings we notice in the next room. It is worth mentioning a couple of them: the first is a Portrait of Sigismondo Ponzone, a small member of the Cremonese family for whom Genovesino worked, and from whose collection the city’s Museo Civico, which houses the exhibition, originated. Elegance and page-like bearing, the guarded big dog that reminds us of portraits from the Spanish area (and specifically those of Velázquez, Mina Gregori pointed out), and a highly original cartouche with a dedication to his father make this four-year-old one of the most intense portraits of seventeenth-century Lombardy. And equally intense is the painting depicting Queen Zenobia, the first and only queen of Palmyra, the city over which she ruled from 267 to 272 A.D. before being defeated and imprisoned by the Roman emperor Aurelian: the work depicts her precisely during her imprisonment, and would demonstrate the author’s knowledge of the drama La gran Cenobia by Pedro Calderón de la Barca, to which Louis Miradori was introduced by his powerful patron, Don Ãlvaro Suárez de Quiñones, Spanish governor of Cremona.

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Sleeping Cupid (canvas, 76 x 61 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Vanitas (panel, 28.5 cm diameter; Breno, Museo Camuno - CaMus) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as Genovesino, Portrait of Sigismondo Ponzone (1646; canvas, 131 x 100.5 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

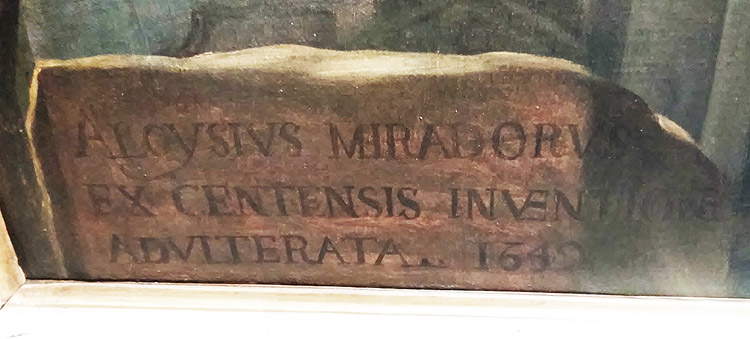

The last two rooms are devoted to altarpieces and paintings executed during the last phase of Luigi Miradori’s career. Among the certain works executed in Cremona are a number of paintings for the abbey church of San Lorenzo: two of these, the Nativity of the Virgin and the Beheading of St. Paul, are now preserved at the Museo Civico “Ala Ponzone” and are on display in the exhibition. Two canvases completely similar in format and style but whose subjects justify two totally different atmospheres: the Nativity is set within a domestic interior described with meticulousness, intense naturalism (the seated fantesca is a woman of the people, revealing Spanish suggestions) and not without a certain taste for the bizarre (the basin and the pitcher, with their monstrous decorations), while in the Beheading it seems that even the landscape and the sky participate in the drama of the saint about to suffer martyrdom at the hands of the muscular tormentor who gathers his strength to deliver the fatal slash with his two-handed sword. The little angels, above near the rosy clouds that recur in Genovesino’s paintings, are already ready to reward the saint with the palm of martyrdom, while below, on the boulder we notice in the foreground and partially obscuring the church in the distance, the artist claims to have been openly inspired by an invention of Guercino (a Martyrdom of St. James the Greater for the church of Saints Peter and Prospero in Reggio Emilia now lost, but known through engravings, a medium by which Luigi Miradori may also have become acquainted with Guercino’s work). All dropped into the theological issues of the time is the Miracle of the Mule, aimed at making the faithful understand the truth of transubstantiation, which is also recognized by the mule that is the protagonist of the painting. Legend has it that St. Anthony of Padua had made a bet with a heretic, the owner of a mule: the animal would be kept on an empty stomach and then spurred to choose whether to fling himself on a sack full of fodder, or to reverence the consecrated host. St. Anthony, as one would imagine, would have won the bet: we see in the painting that the mule, despite fasting, chooses to kneel before the body of Christ, to the amazement of his master and onlookers, at the end of a street that for Valerio Guazzoni could be linked to memories of the artist’s homeland (the monumental context would indeed seem to be that of Genoa’s Strada Nuova).

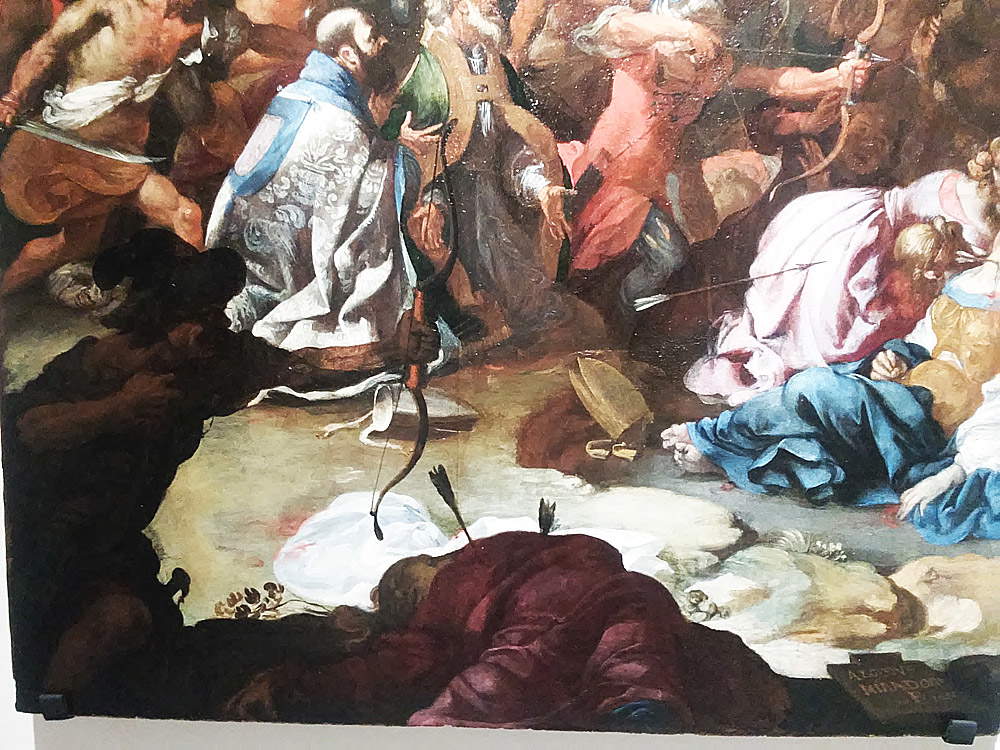

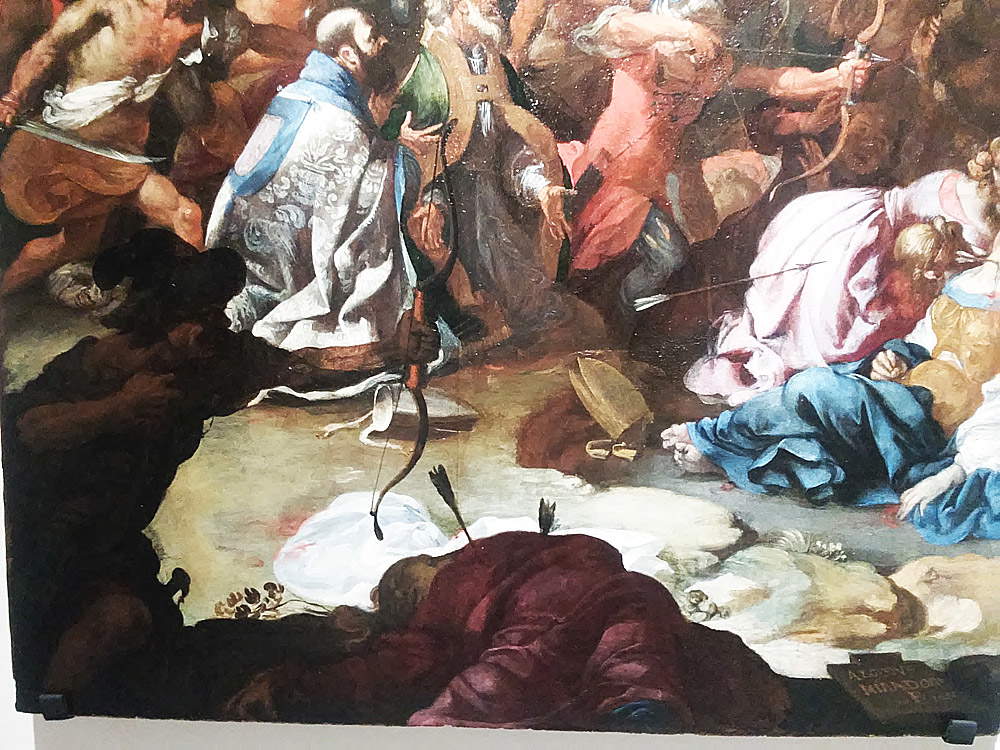

In the last room we are greeted by theAnnunciation of San Martino dell’Argine, a painting “of great charm and aristocratic compositional setting” (Marco Tanzi), compromised, however, by suboptimal conservation that has led to color falls. The archangel arrives from the left, on a cloud, inside a building of classical breath, and finds before him an elegant Madonna already kneeling and with delicate hands on her chest, and above a tangle of putti rushing to witness the scene: it is a work with a complex history, which was reconstructed on the occasion of the exhibition thanks to the decisive contribution of two very young scholars (Martina Imbriaco and Giorgia Lottici), who are credited with having found, in the Parish Archives of Marcaria, a document that attests to the name of the commissioner, Marquis Giulio Cesare Mainoldi, and that of the church in which the painting was originally located (the oratory of the Madonnina di San Martino dell’Argine). Past the St. John Damascene mentioned in the opening, the visitor will find before him a pair of very interesting panels, one depicting the martyrdom and the other the glory of St. Ursula: for these paintings, too, the exhibition has provided an opportunity to reconstruct their vicissitudes, thanks to the work of Giambattista Ceruti, who has proposed identifying them as two ornaments of the apparatus that, in 1653, was set up in San Marcellino in Cremona to receive a relic of the Cremonese bishop Bassanus from Germany, the land where he had suffered martyrdom. The story of Saint Bassanus is in fact linked to that of Saint Ursula, together with whom he was martyred in Cologne: in the first work we see him in the midst of general disarray (tradition has it that Ursula was killed together with the eleven thousand virgins who had accompanied her on a pilgrimage to Rome), in the second while he is in heaven together with his companions who ascended among the blessed. These are two paintings marked by great immediacy, by very high emotional participation in a tremendous drama (the depiction of martyrdom is probably one of the most violent in the entire history of art), by unusual iconographic solutions (St. Ursula, in the painting of the martyrdom, is in the background) and by real pieces of virtuosity (such as that of the henchman in the foreground who, against the light, shoots an arrow from his bow).

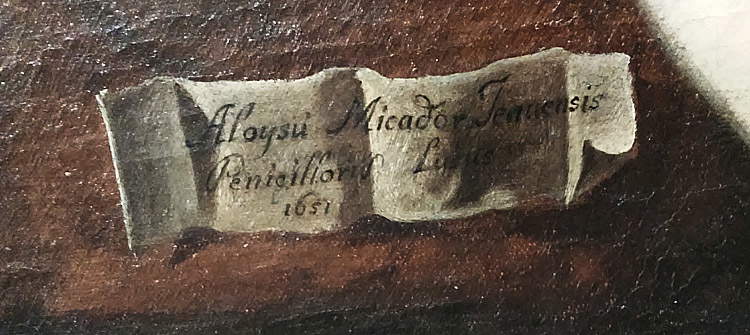

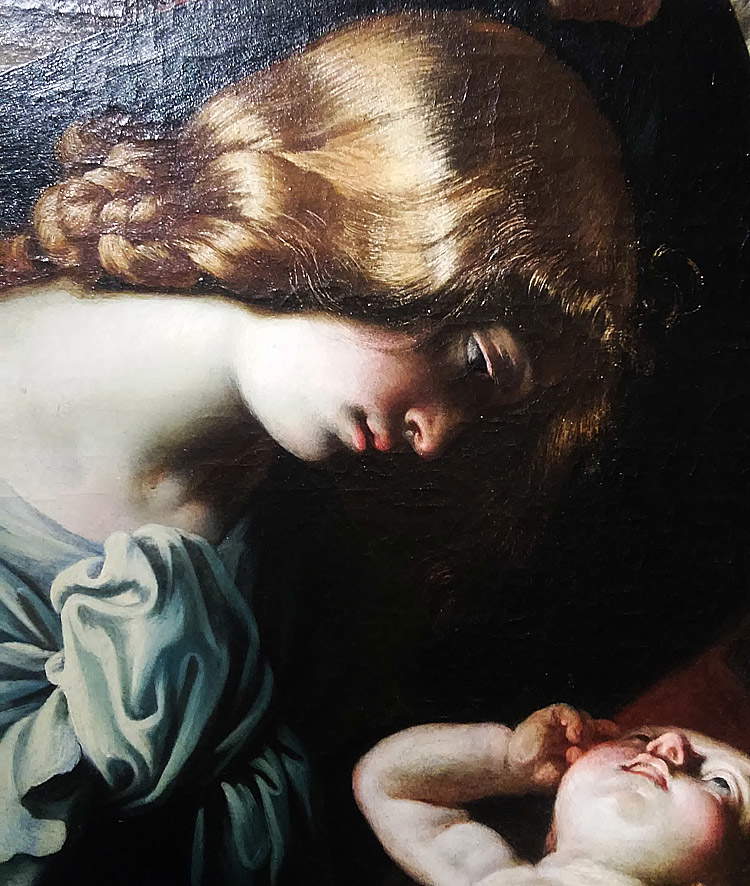

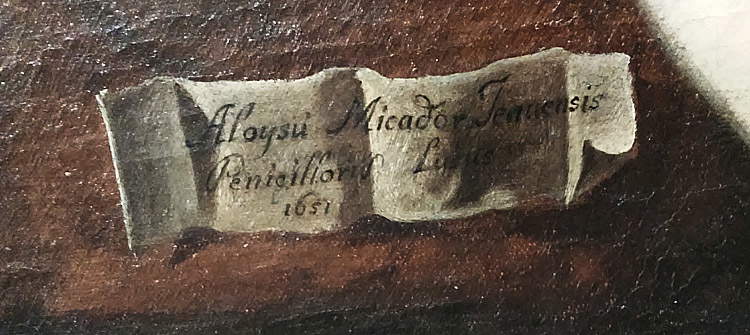

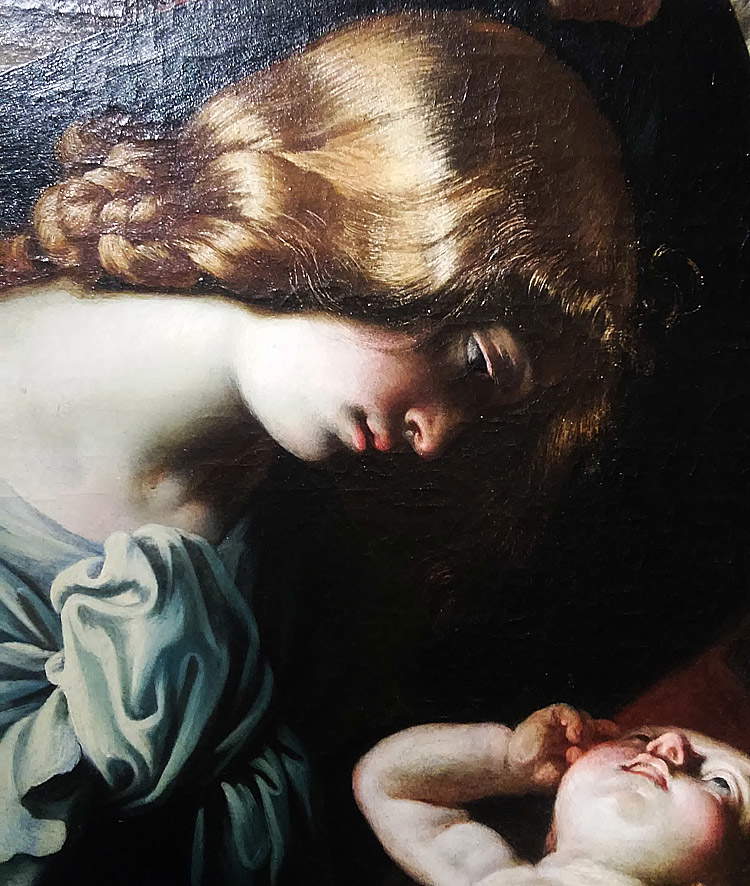

The altarpiece with the Saint Lucy of Castelponzone, and its smaller replica from a private collection, accompany us toward the work with which we can bid farewell to the exhibition: the Rest during the Flight into Egypt, a complex work from the late phase of Genovesino’s career, “to be counted among the most intense and original interpretations of the Gospel episode offered by seventeenth-century painting” (so assures the catalog entry prepared by Francesca Bazza, Pamela Cremonesi and Lisa Marcheselli, other young scholars involved in the project). Genovesino himself was alert to the fact that the canvas represents one of the most bizarre Rests of the time: in fact, the artist’s signature is accompanied, in the tag on the lower right, by the formula penicillorum ludus (“brush game”). The main scene takes place on the left: a naturalistic, blond adolescent Madonna welcomes on her lap a stretching baby Jesus while St. Joseph leans on his staff as usual, but is almost about to be embraced with his wings by the angel who stands beside him and participates in the intimacy of the moment by bringing his hands to his chest. To add to the naturalism, another angel arrives with a shawl to cover Mary’s shoulders, while the sentimental intonation of the scene in the foreground is further ensured by the two putti on the lower border: however, were it not for the wings, the latter would appear to us to be destitute of any celestial attributes, since they seem, if anything, to be two tender children, a little girl bringing dates to the Virgin, and a little boy holding the sack of fodder to the donkey. Serving as an architectural backdrop are classical ruins on which, in the distance, the motif of the flight to Egypt is consumed: the slaughter of the innocents, depicted with stark drama (note the bodies falling into the void). Precisely what happens in the background is the reason that erases any smile from any face: all the characters, from the holy family to the two angels in the foreground to the group of cherubs fluttering in the sky, are pervaded by a veil of worried sadness. This is a great masterpiece, dated 1651, that assimilates most of the characteristics of Genovesino’s style: Lombard narrative accents, Caravaggio-like realism, vivid coloring, extreme iconographic versatility, and a certain Baroque theatricality. Characteristics that, as we leave the Museo Civico, we can find in the Cathedral’s Stories of St. Roch (pay attention to opening hours: the city’s main house of worship closes between noon and half past three), or in the two large paintings preserved at the Palazzo Comunale, the extraordinary Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes, an enormous canvas of popular taste measuring almost five meters by eight, or theLast Supper in which the Gospel episode seems almost (as it was for the unpublished Last Supper mentioned above) to be set in a dive bar of the time. Both the Cathedral and the Palazzo Comunale can be considered an integral part of the exhibition itinerary.

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Birth of the Virgin (1642; canvas, 188 x 276 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Beheading of St. Paul (1642; canvas, 190.5 x 260 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

|

| The boulder with the reference to Guercino |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Annunciation (canvas, 280 x 190 cm; San Martino dell’Argine, Saints Fabian and Sebastian) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Martyrdom and Glory of St. Ursula (both: 1652; panel, 208 x 85.2 cm; Cremona, Santi Marcellino e Pietro) |

|

| Detail of the foreground of the Martyrdom of Saint Ursula |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Rest during the Flight into Egypt (1651; canvas, 328 x 220 cm; Cremona, Sant’Imerio) |

|

| Angel in the foreground in the Rest during the Flight into Egypt |

|

| The card in the Rest during the Flight into Egypt |

|

| Our Lady in the Rest during the Flight into Egypt |

|

| Genovesino’s Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes in the Cremona Town Hall |

An exhibition that proposed a critical reappraisal of Genovesino was needed. The gap has finally been filled, with a major exhibition that brings together much of the artist’s known output and also extends to the rest of the city. An exhibition of reconnaissance and research, as indeed happens with every first monographic exhibition, all the more so since it has forced, write the three curators, “to bring order to the career” of Genovesino, with a job that is anything but easy, given that there are not many fixed points that punctuate the parabola of this whimsical seventeenth-century painter, adept at deftly probing the most varied registers, from the lofty one of religious art to the trivial one of genre painting, without disdaining the macabre and the bizarre and being at ease also with an intimate lyricism, with a committed art pregnant with literary references, with the naturalism typical of the century and characterized by a typically Lombard narrative verve. A painter so accustomed to moving on several levels, that attempts to draw up a precise chronology would be in vain, so much so that, prudently, the curators do not venture to hypothesize dates for paintings that are not strong enough: in this sense, the exhibition (whose project has involved many young people from the Department of Musicology and Cultural Heritage of the University of Pavia, which is based in Cremona) is therefore also a “moment of verification” on which scholars can compare notes. A true art history exhibition, in short, the kind that allows the subject to progress, and also decidedly interesting for the public.

Genovesino, it should be emphasized, is not only an artist of local scope: he is an extremely fascinating painter, who was able to grasp, despite the limited geographical territory in which he moved, cues from even very different artistic realities, and to descend within his restless figurations is tantamount to opening a seventeenth-century history book. Beyond the sure scientific interests, there were therefore all the prerequisites for an exhibition capable of speaking clearly and compellingly to the general public: the expectations, in this sense, have not been disappointed, since the exhibition also avails itself of a very effective didactic path, with a very useful app for smartphones and tablets, free to download, which contains additional information and descriptions of most of the paintings on display. The catalog published by Officina Libraria, with its four concise but comprehensive essays (on critical fortune, youthful experiences, activity in Cremona, themes) serves as an up-to-date monograph on Genovesino and marks a new, important point of reference for studies on the artist.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.