It sometimes happens that a selection of works from a famous international museum moves en bloc to create an exhibition in Italy with masterpieces from that museum venue alone, generally emphasizing the concept and the extraordinariness of the event already in the title itself, which sees the repetition of the now usual formula “Masterpieces from... ” followed by the famous lending museum of the day. An operation that can be shared or not that nevertheless gives the opportunity to admire masterpieces from important foreign museums in Italy without going abroad. It had happened in 2018 with the exhibition Impressionism and the Avant-Garde. Masterpieces from the Philadelphia Museum of Art at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, or at the turn of 2022 and 2023 with the exhibition Van Gogh. Masterpieces from the Kröller-Müller Museum at the Palazzo Bonaparte in Rome, or again in 2019 with the exhibition Pre-Raphaelites. Love and Desire also at the Palazzo Reale in Milan (the exception here is the title, which does not carry the usual formula) with masterpieces all from Tate Britain in London. And now, in an entirely similar fashion, this model is being proposed again in Padua, with the exhibition Monet. Masterpieces from the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris, open to the public until July 14, 2024 at the Centro Culturale Altinate San Gaetano, curated by Sylvie Carlier, director of collections and chief conservator of heritage at the Musée Marmottan Monet, in collaboration with art historian Marianne Mathieu and Musée Marmottan Monet conservator Aurélie Gavoille.

Thus, sixty masterpieces from the museum that holds the world’s largest collection of Claude Monet ’s canvases have arrived in Italy for the Padua exhibition to narrate the various stages of the painter’s artistic research, from his beginnings to his stays in the Netherlands, Norway and London, and on to his large canvases with Water Lil ies and Wisteria. Through the six exhibition sections, visitors have the opportunity to retrace the key moments in the production of the master of Impressionism in the year that marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of the French movement, that is, from that first Impressionist exhibition held in Paris, in the studio of photographer Félix Nadar, at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, on April 15, 1874. And to take a closer look at many of the works that Monet himself jealously guarded, without ever wanting to part with them, in his home in Giverny until his death, and that now belong to the collection of the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris thanks to the bequest of more than a hundred works that his son Michel Monet, the painter’s sole heir after the death of his brother Jean, decided to dispose of in 1966 to the Académie des beaux-arts. In fact, Michel Monet’s will designated the Académie as the universal heir to the Giverny estate, the Japanese prints, Claude Monet’s collected works by artists such as Delacroix, Boudin, Renoir, Caillebotte, and Pissarro, and the last canvases made by the painter in his atelier in Normandy. The Musée Marmottan, which brought together the collections of Paul Marmottan and was one of the foundations of the Académie des beaux-arts, therefore became with Michel Monet’s donation the custodian of the world’s largest fund of paintings belonging to all stages of the Impressionist painter’s career; to accommodate this large collection of works, the then director of the museum Jacques Carlu designed a space carved out under the garden that was inaugurated in June 1971. And it was not until 1999 that Monet’s name was added to that of the Musée Marmottan.

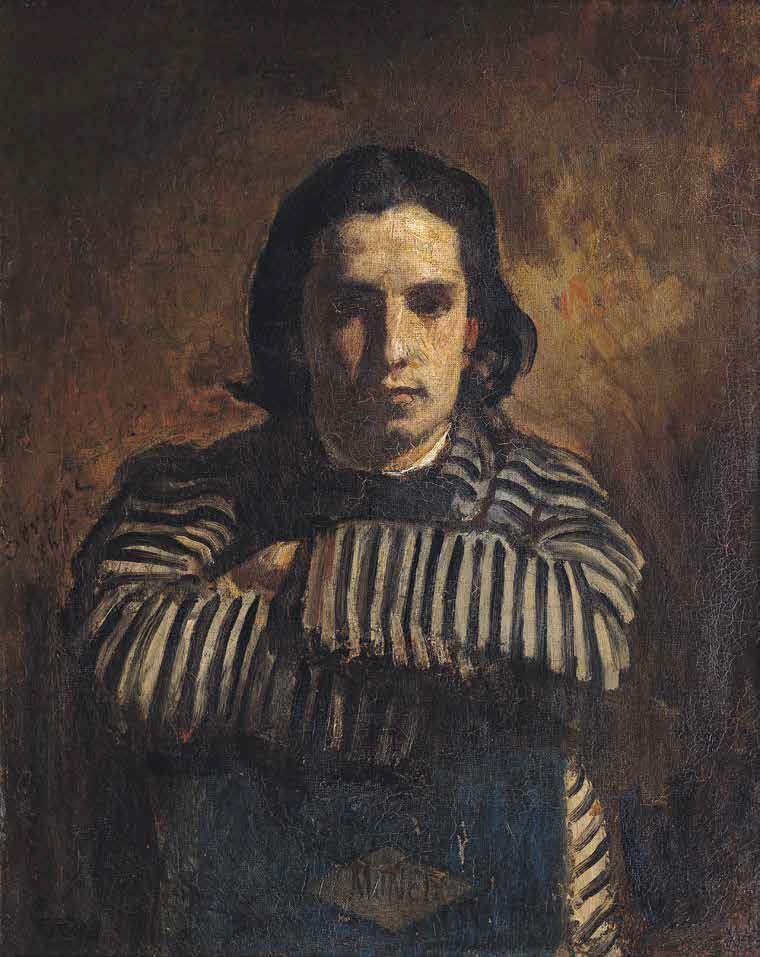

In fact, the exhibition in Padua opens with the Portrait of Michel Monet with a Pompom hat, made in 1880 when Michel was only two and a half years old-a portrait that was never exhibited and remained in the family until his death in 1966, and that thanks to the important bequest entered the collections of the Paris museum. Next to it, on the other hand, is the plaster bust portraying Claude Monet made by dentist Paul Paulin between 1908 and 1910, and which he himself gave to the painter: encouraged by Edgar Degas to sculpt, Paulin in fact began to make portraits of personalities of the time, including Monet. In contrast, the portrait displayed here of a young Claude Monet by the painter Carolus-Duran, which is also part of Michel Monet’s bequest, dates from 1867. The work is part of the gifts received by Claude Monet directly from artist friends, as is also the portrait also exhibited here that Pierre-Auguste Renoir paints of Monet reading the newspaper L’Événement and smoking a pipe, as if he were one of the family, or again the portrait that Gilbert Alexandre de Séverac paints of a 24-year-old Monet by limiting the color range to brown tones against a neutral background. The collector Monet is then witnessed in the exhibition by works by Johan Barthold Jongkind and Eugène Delacroix purchased by the painter between 1891 and 1900, and by watercolors by Eugène Boudin, such as Crinoline on the Beach.

To tell the story of Claude Monet’s painting, one cannot but speak of Impressionist light and en plein air painting, and indeed these two themes are addressed in the exhibition in two separate sections, one after the other, but in fact in the paintings of what is considered the father of Impressionism one permeates the other: the light, with its reflections, that floods Impressionist landscapes is inherent in the paintings that the painter makes in theopen air, and it is equally true that en plein air painting always sees the presence of that unique light that is transposed from nature to the canvas, considering that not the actual colors are represented, but rather the interpretation of them according to the light. A combination that is here well witnessed in the painting The Trouville Beach, which Monet made in the summer of 1870, when the painter, his wife Camille and their first son Jean are in the seaside resort of Trouville, Normandy, where they meet Eugène Boudin, a painter who specialized in beach scenes. Here Monet depicts Camille and her cousin sitting in the foreground, but he focuses mainly on the effects of light between the sky and the sea, and also on the clothes of the two women, as well as on the study of painting en plein air, whereby everything in the background is less defined than what is in the foreground. And the color scheme chosen for this painting, in shades of gray, white and brown, also harks back to early Monet. As is also seen in the juxtaposition of two paintings, one of them very famous, which both rely on shades of gray (of the sky) and white (of snow): Effect of Snow, Setting Sun and The Train in the Snow. The Locomotive, both from 1875 and both made in Argenteuil. Winter views that allow the painter to measure himself with new effects of light and contrast, highlighting his skills as a colorist. The en plein air painting section notably brings together works that Monet had occasion to make during his sojourns both elsewhere in France and abroad, such as in the Netherlands, Norway, and London. They are mostly works characterized by a color palette that becomes more “colored” and lighter than the earlier grays, and by a denser pictorial matter, with brushstrokes clearly visible on the canvas.

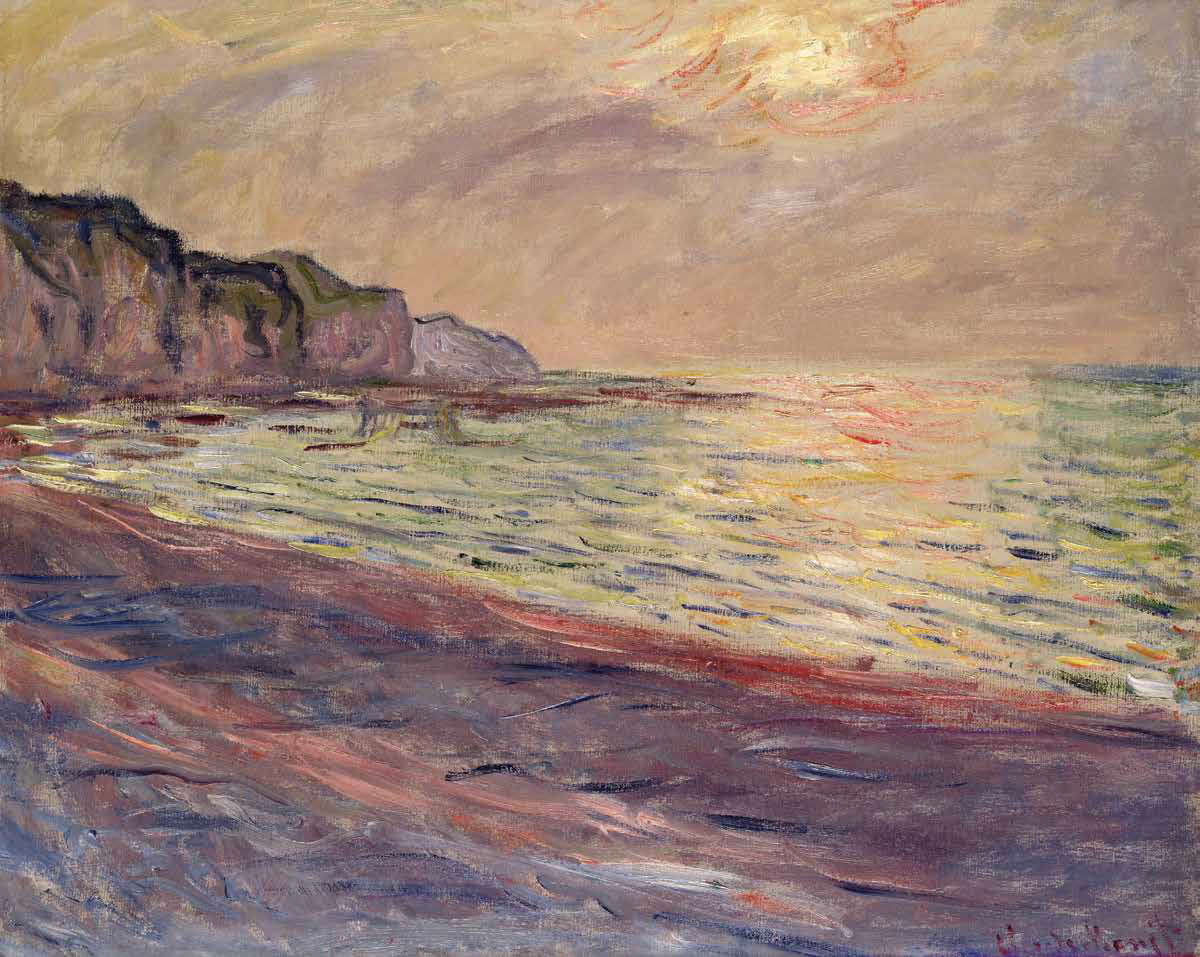

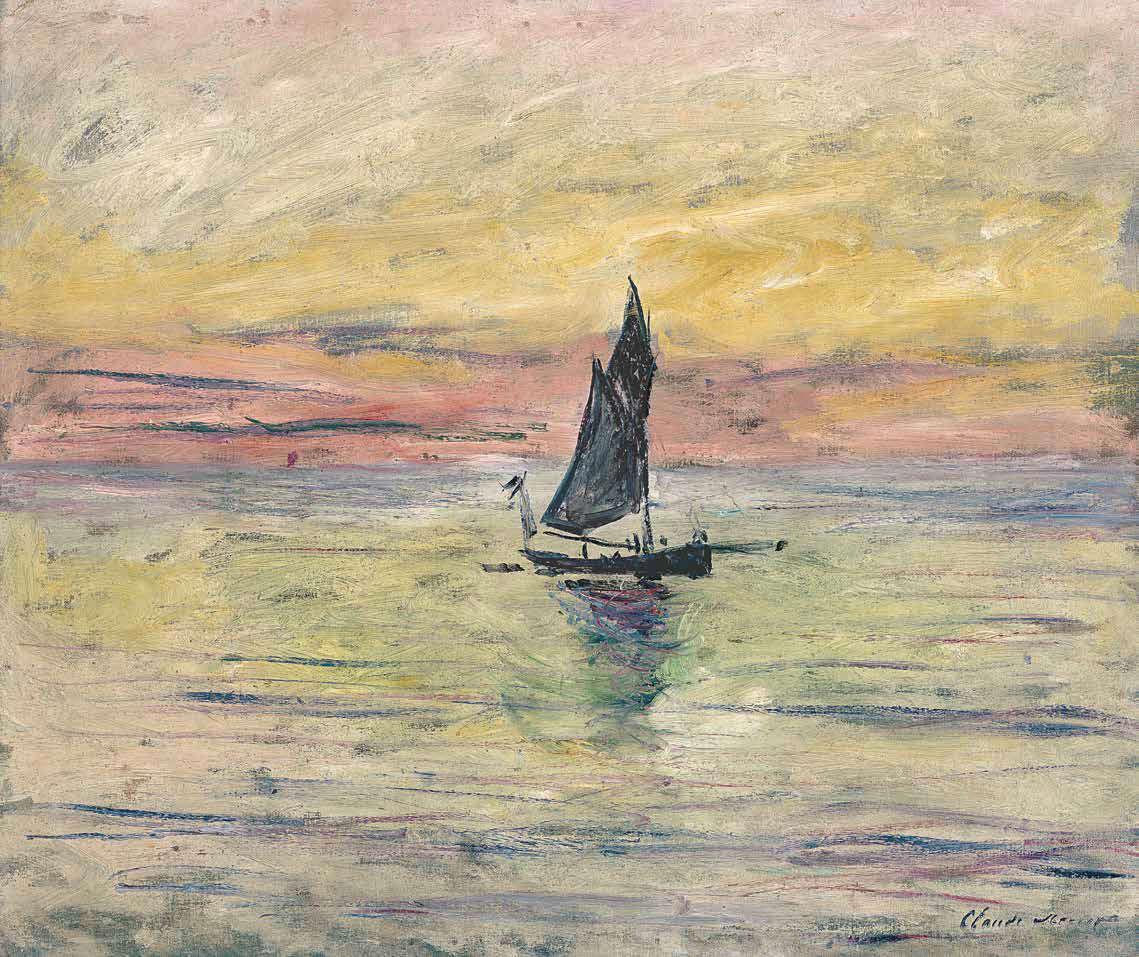

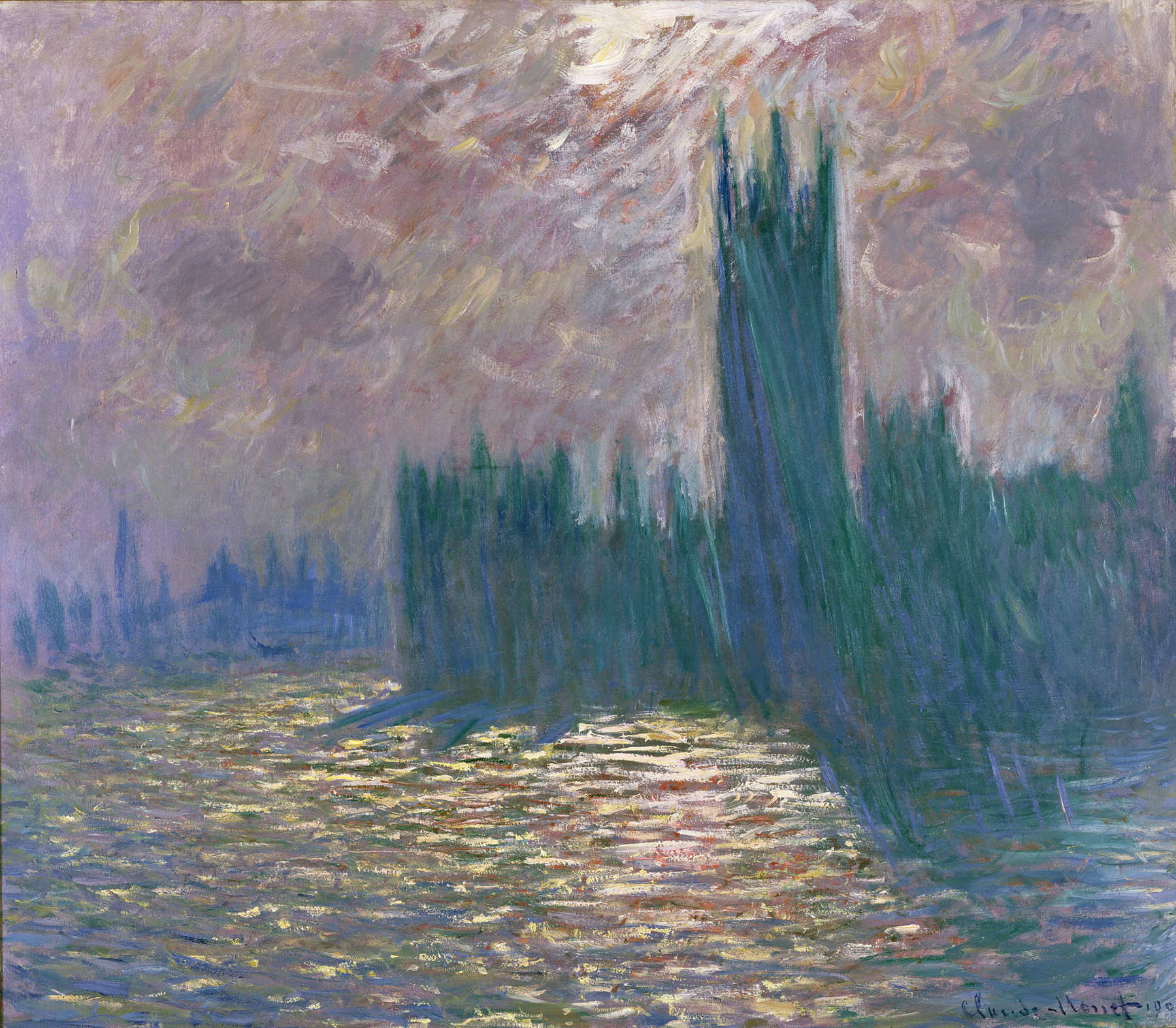

Then follow before the viewer’s eyes The Pourville Beach, Setting Sun, in which the painter renders the variations of light and the setting sun reflecting on the sea, the beach, the cliffs and creating suggestive hues in the sky; Sailboat, Evening Effect, painted on the beach at Étretat: a sailboat is depicted darkly in the center of the marina, contrasting with the pastel tones ranging from yellow to pink that occupy the entire scene and create a solution of continuity between sky and sea; Field of Yellow Irises at Giverny, in which the flowers are rendered with juxtaposed yellow touches that become increasingly broad brushstrokes in the background. The work is reminiscent of paintings the artist made in the Netherlands, where he stayed twice, as in Field of Tulips in Holland exhibited here. The man depicted half-length with hat looking at us sideways is Poly, diminutive of Hippolyte Guillaume, a lobster fisherman who for two francs a day became Monet’s porter during his stay from September to November 1886 on Belle-Île-en-Mer, a French island off the coast of Brittany, and who at the same time accompanied the painter in discovering the island’s wild character. We then move on to the en plein air Nordic painting of Norway, where Monet stayed between February and March 1895, taking advantage of the presence in the Scandinavian state of Jacques Hoschedé, the eldest son of his second wife Alice. And so here is Norwegian Landscape. The blue houses: the painter was deeply fascinated by a small village with wooden houses surrounded by snow: the brown of the houses contrasts with the white of the snow and the changing hues of the sky in shades of yellow and orange. And from Björnegaard’s red houses, colorful houses that reminded him of the Japanese villages he had come to know through prints purchased in Holland and Paris and kept in his home in Giverny. And finally, painting en plein air in London, where the artist stayed several times from 1870 to 1901. It is exhibited here, next to Charing Cross Bridge. Smoke in the Fog. Impression (1902), the 1905 painting that depicts against the light the silhouette of Parliament at the hour of sunset, a device that allows him to create shimmering reflections on the Thames. This is also one of the most striking rooms in the exhibition itinerary: in fact, a circular seat has been placed in the center of the room on which images of some of the painter’s thematic works are projected. Perhaps Monet’s most famous work, the one that arguably started Impressionism, or Impression, soleil levant, would have found its rightful place in this section of en plein air painting: the famous painting belongs to the collection of the Musée Marmottan Monet but is now extraordinarily on loan to the Musée d’Orsay for the current exhibition until July 14, 2024 Paris 1874. Inventing Impressionism, which celebrates the first Impressionist exhibition held in Paris in 1874, exactly 150 years ago.

Another pivotal chapter in Monet’s life and art is, of course, the move to his Giverny estate, where he spent the last two decades of his existence surrounded by his canvases, which were populated with flowers, and especially his garden. Indeed, this is precisely the theme of the next section: the visitor finds himself surrounded by canvases with irises with blue-purple petals, hemerocallids and water lilies, flowers that were found in his splendid water garden at Giverny, in which the weeping willows that the painter had planted around the pond were also reflected. Then there is a painting that depicts in the upper right-hand part of the canvas a boat, the one on which his second wife’s daughters, Suzanne and Blanche Hoschedé, often boarded to sail as a pastime on the waters of the Epte River, which flowed right by the Giverny house. In fact, as is similarly the case with the water lilies, the subject of the boat is an opportunity for Monet to concentrate on the aquatic grasses and the reflections with their multiple colorations on the water, here rendered in the form of real filaments. A vitrine also encloses on display the palette, post-surgery glasses from bilateral cataracts (which the painter was diagnosed with in 1912) and Monet’s pipe, which came from the Musée Marmottan.

And again, there follows an almost circular room at the center of which is a seat showing rotating images of water lilies: canvases with water lilies and irises, this time yellow, return on the walls. The theme is the Grand Decorations: the monumental panels with water lilies, which Monet worked on until his death, that led to the creation of the famous oval rooms of theOrangery.

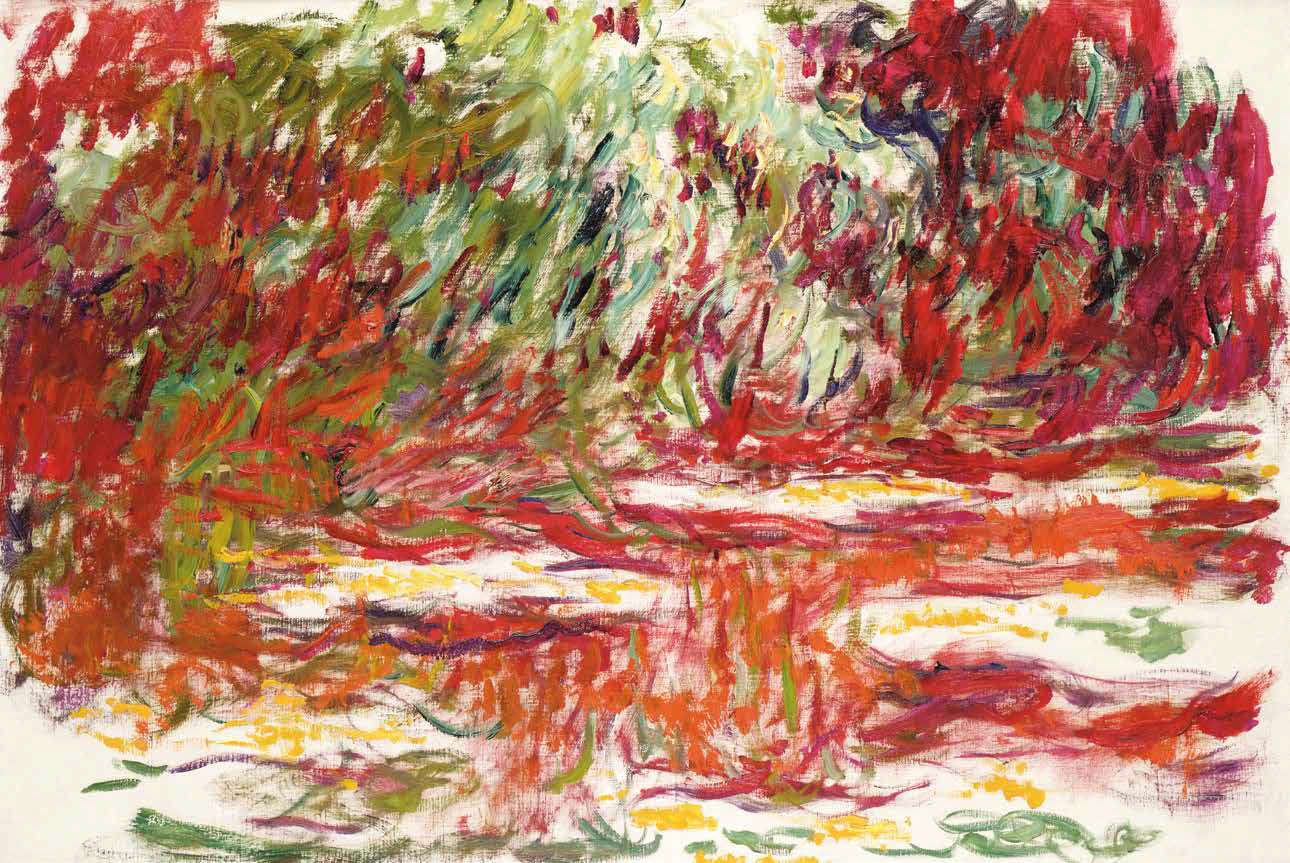

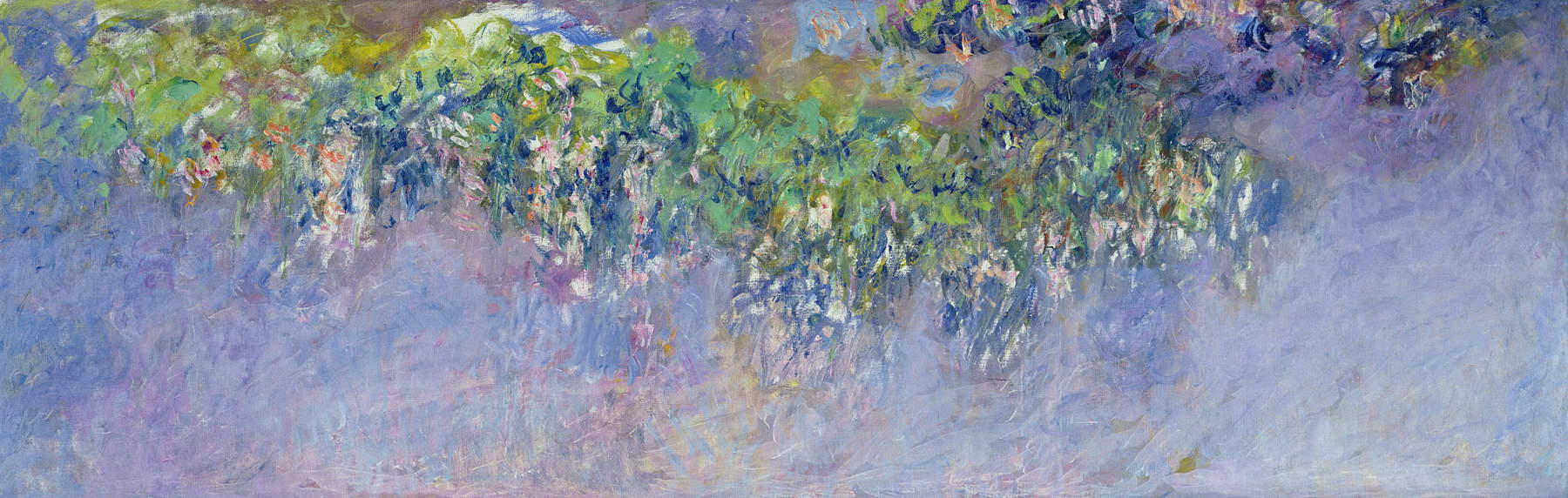

Finally, the last section documents a marked change in both colors and forms, even going almost toabstraction, as in the case of the painting The Garden of Giverny, where realistic details are eliminated while retaining only broad chromatic masses-a mode that would influence the American abstract painters of the second half of the 20th century. Browns, reds, and yellows dominate in these works, as seen in Water Lily Pond, Avenue of Roses, Japanese Bridge , or Weeping Willow. A change dictated by the vision problems that altered his perception of colors, but which probably led him unconsciously to an extremely modern and even more gestural painting. The exhibition concludes with two large elongated canvases dedicated to wisteria, plants that in the Giverny house climbed and fell on the arch installed on the Japanese bridge. Their large size and elongated form required a suitable location: they were in fact intended to decorate the garden pavilion of thehôtel Biron in Paris (today’s Musée Rodin), but the project was abandoned in favor of the Orangerie display. Now preserved at the Musée Marmottan Monet, these Wisteria that also veer toward abstraction with extraordinary evanescence were never exhibited while the painter was still alive.

Through all these works that arrived en bloc from Paris, therefore, Monet’s entire artistic universe and the themes that characterized his production are retraced, from his beginnings to the Great Decorations that flowed into abstraction. A chronological journey marked in a linear way in the different thematic sections also enriched by a didactic path on light and colors. Although it essentially adds nothing to our knowledge of the father of Impressionism, visiting the exhibition in Padua is an opportunity not to be missed if you have never been to the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris, the museum that every fan of the great painter should visit at least once in a lifetime.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.