From Pasquale Rotondi to Fernanda Wittgens, our monuments men who saved art: the exhibition in Rome

Without a true love of art, which also goes beyond what an insider’s profession requires, and sometimes without a courageous spirit, numerous masterpieces that we can still admire in our museums today would most likely no longer be in Italy. This is the reflection that those who visit the major exhibition at the Scuderie del Quirinale Arte liberata 1937-1947. Masterpieces Saved from the War, running until April 10, 2023, curated by Luigi Gallo and Raffaella Morselli and organized by the Scuderie del Quirinale in collaboration with the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, the ICCD - Istituto Centrale per il catalogo e la Documentazione and the Archivio Luce - Cinecittà, is inevitably led to make. With this important exhibition, the Scuderie del Quirinale intends to recall, as Ales spa Scuderie del Quirinale president and CEO Mario De Simoni states, “the far-sighted action of the many Superintendents and officials of the Fine Arts Administration who, in the steel storms of the war, found the strength, ideas and means (usually scarce) to tackle one of the great undertakings of the era: the preservation of Italy’s immense historical and artistic heritage at war. A heritage put at risk even before the war by forced exports to the Third Reich, then during the war by Allied bombings, Nazi raids and generally by the movement of the front along our territory. With their action, of universal significance, they contributed to affirming the value of cultural heritage as a founding element of a more complete civic and national identity.” Thus, the exhibition aims to pay tribute to "a group of young officials of the Fine Arts Administration who, assisted by art historians and representatives of the Vatican hierarchies, were the interpreters of a patriotic feat of preservation conducted with very limited means."

Visitors will leave this exhibition event enriched by the narrative that, section after section, will be provided to them of the course of History, from the Führer ’s dream of creating in Linz, Austria, a museum where art masterpieces expressing the values and tastes of the Nazi regime could be brought together to the activity of the Monuments Men, but above all of the stories of all those people in Italy who made their fundamental contribution in saving works of art during the years of World War II, aware of the universality of artistic and cultural heritage. “This is an exhibition of stories. Of stories of women and men, of difficult and silent heroisms, of works of art protected, lost, saved and finally recovered,” says De Simoni. History and the stories of these protagonists who refused to join the Republic of Salò are mutually intertwined along the exhibition itinerary consisting not only of works of art among those saved during the World War (more than a hundred) from the museums that still (fortunately) preserve them today, but also of photographs and documentary material; all enriched by comprehensive explanatory panels that narrate the various events and make the succession of sections clear in intent and comprehensible, without being heavy despite the length of the itinerary and the wealth of materials.

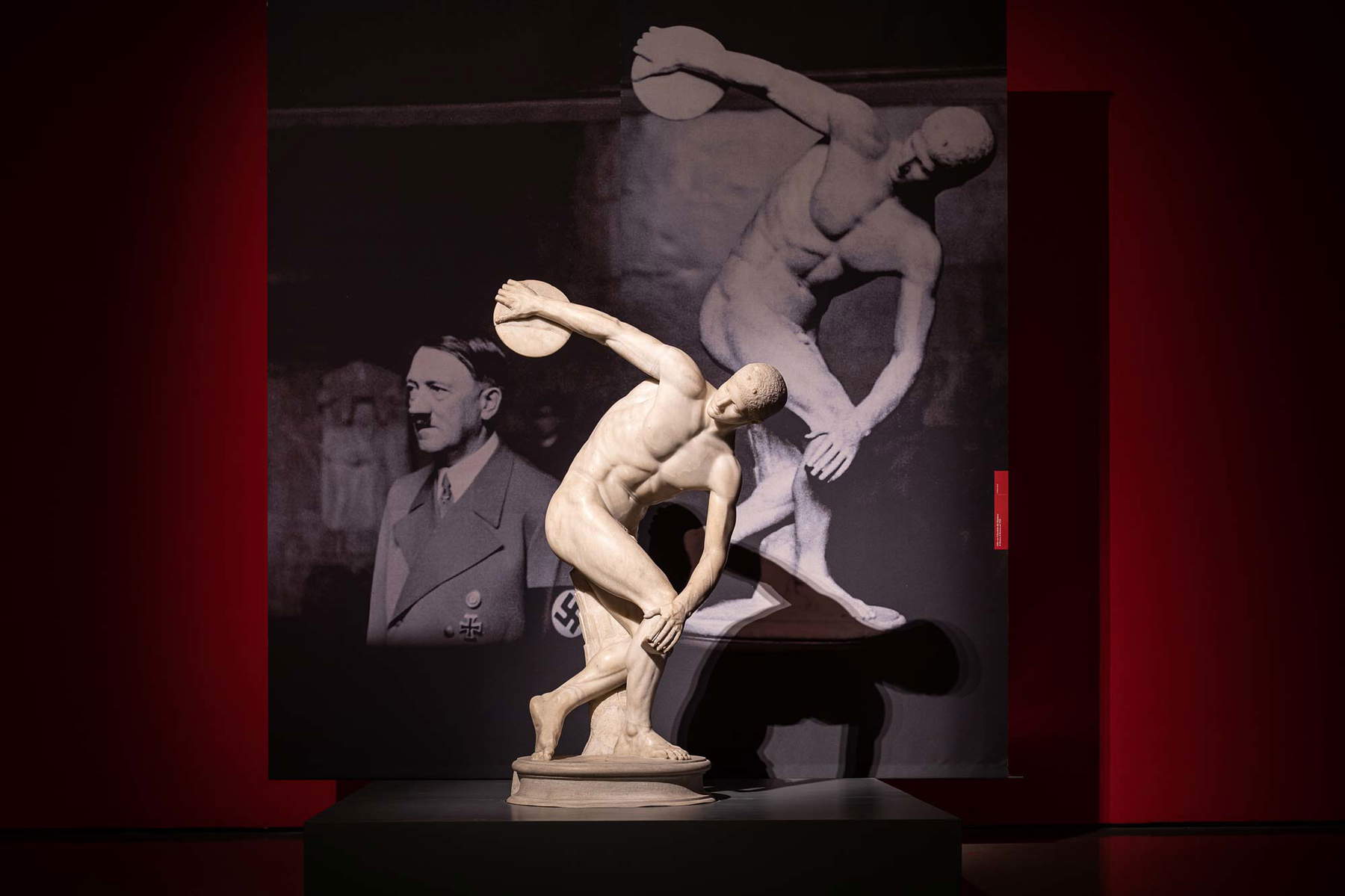

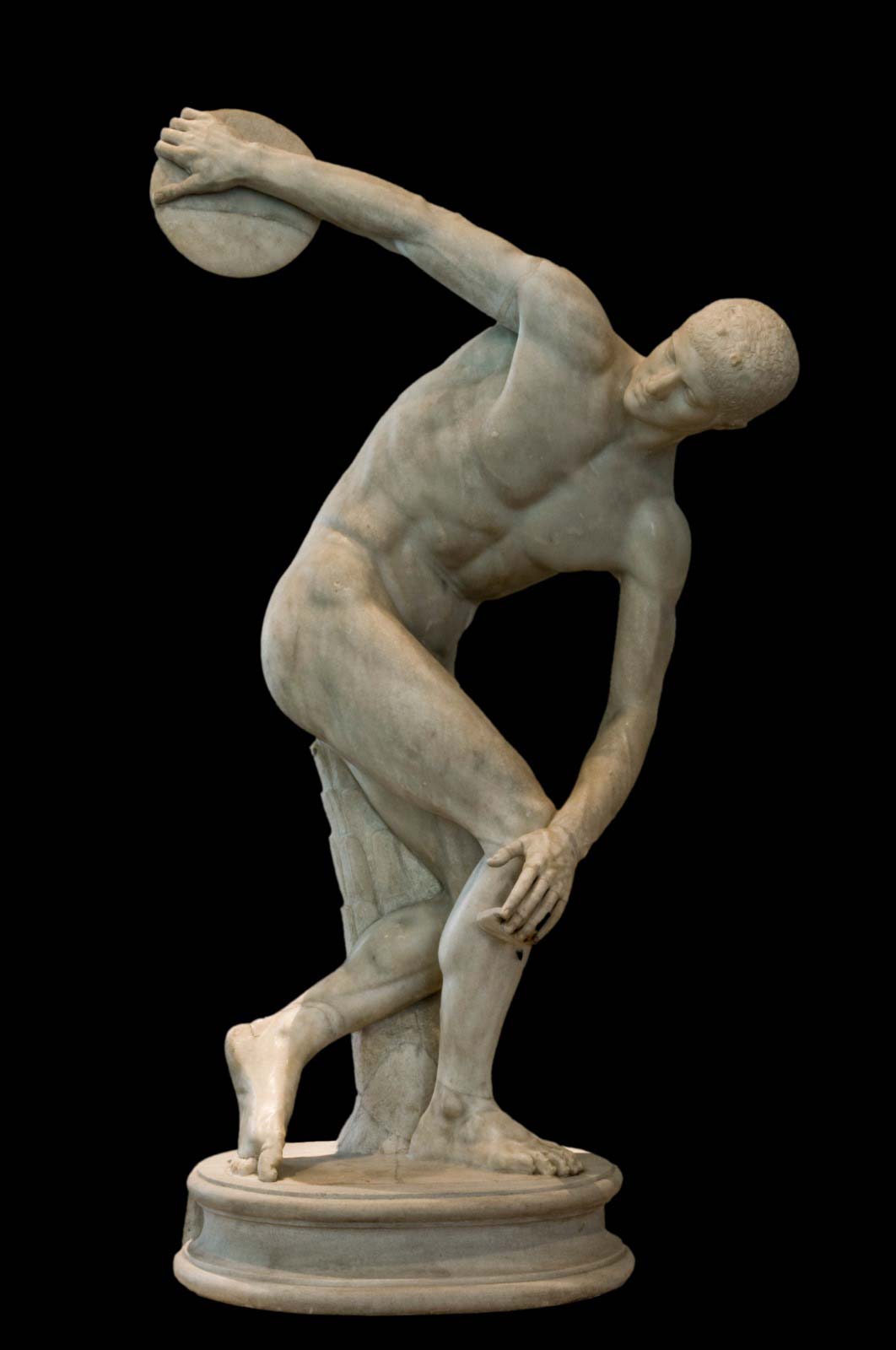

The beginning of the exhibition is entrusted to the Lancellotti Disk from the Palazzo Massimo at the Baths in Rome, a Roman copy from an original by Myron: the sculpture was in fact among those that Hitler wanted for his museum in Linz, through which he wanted to celebrate the greatness of the Third Reich. Not only German art then, but also all those works that could represent the values of classicism and Aryan perfection expressed by European civilization sinceclassical antiquity. As Gianluca Scroccu recalls in his essay, where he outlines Hitler’s biography in relation to his artistic ambitions (even as an artist), since his 1938 visit to Italy, requests for loans of famous works by the Nazi government were increased, and our country was considered a real treasure to be accessed voraciously, exploiting the relations between the two Axis powers. The commission to purchase the works of art was headed by Prince Philip of ’Hesse, husband of Mafalda of Savoy, who in 1938 requested permission for the Lancellotti Discus, which had been under bond since 1909, to be transferred to Hitler, and, as curator Luigi Gallo, current director of the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, recalls in his essay, in which he outlines a history of tutelage during the years of World War II, the work was granted, despite the negative opinion of the Superior Council of Sciences and Arts, "through the direct interest of Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano, and on June 9, 1938, it took its place in the Glyptothek in Munich as a gift from the Führer to the German people." The Discobolo, together with a nucleus of works illegally exported by the Nazis before September 8, made its return to Italy in November 1948. It is thus emblematic of those works that left Italy only to please the Führer and his hierarchs and were later recovered after the conflict.

It is then recounted in the exhibition how Education Minister Giuseppe Bottai, following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, sensed that Italy would soon enter the war and, fearing air raids, was concerned about theimmense Italian artistic heritage, which had to be saved like families and homes, and ordered the monuments, which were marked with a distinctive sign on the roofs, to be secured and the movements of the works, divided by category of importance, to be worked out. In fact, as early as 1938 the minister had sent a circular to the Superintendencies to arrange for the classification and listing of all the material to be subjected to protection in case of war into three distinct groups: the “goods of greater value” to be moved to shelters, the “goods of high value” immovable due to fragility and size to be protected in situ, and “goods of secondary importance” also to be protected in situ. The exhibition, while reiterating Bottai’s role in safeguarding heritage during the war, does not, however, mention in the exhibition itinerary the responsibilities that the minister himself had on the events recounted toward the conclusion (which will therefore be discussed later), namely the spoliation of Jewish property as a result of the racial laws, which Bottai (a signer, moreover, of the Manifesto of Race), as minister ofEducation, enforced strictly within his sphere, and which led to some measures directly signed by the minister, such as the circulars on the “defense of the national artistic heritage in Jewish hands,” through which Bottai instructed ministerial officials to hinder (through vetoes and tax increases) the outflow of goods of considerable artistic interest in the possession of Jews who, affected by the persecution, including economic persecution enacted by the regime, sought to take them out of the national borders.

Returning instead to the protection of buildings in the run-up to the war, churches and monuments were propped up with masonry supports and stuffed with sandbags, as seen in the archival photos displayed along the route, frescoes, statues and fountains protected by wooden armor, while paintings and sculptures relocated to places deemed safe. Of the latter point, Pasquale Rotondi, the protagonist of the second and third sections of the exhibition, became a key figure. Since 1939 Superintendent of the Galleries and Works of Art of the Marches, Rotondi was commissioned by Minister Bottai to transport and store a high number of works in the Ducal Palace in Urbino, which was considered safe because of its decentralized location, but he realized that the city could be a military target because of an air force arsenal hidden in a tunnel in an Urbino hillside. He then deposited the works from the Ducal Palace, churches and civic museums of the Marche region in the Sassocorvaro fortress, designed in the second half of the 15th century by Francesco di Giorgio. The hundreds of works transferred to Sassocorvaro include, to give one example, Piero della Francesca’s Madonna of Senigallia, which the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche loaned to the Scuderie del Quirinale exhibition to pay homage to the memory of Pasquale Rotondi’s feat, as well as Bartolomeo della Gatta ’s Salvator Mundi (once given to Melozzo da Forlì). Remaining in Urbino, however, were works by Giovanni Santi ( Tobiolo and the Angel and San Rocco are on display here) and masterpieces by Federico Barocci, represented in the exhibition by the sketch of the Pardon of Assisi and theImmaculate Conception. The masterpieces that came instead from the civic museums of the Marche to Sassocorvaro include Giovanni Bellini ’s Head of John the Baptist (which is now, however, no longer on view in the exhibition having meanwhile moved to the exhibition on Ercole de’ Roberti and Lorenzo Costa in Ferrara), the predella with Paolo Veneziano ’s Stories of the Virgin and the Deposed Christ Supported by Two Angels by Marco Zoppo, from Pesaro, Carlo Crivelli ’s Second Triptych of Valle Castellana and Carlo Maratta’s Saint Francesca Romana, from Ascoli Piceno, Olivuccio di Ciccarello ’s Dormitio Virginis and Guercino’s Saint Palazia , from Ancona, and Lorenzo Lotto ’s Visitation andAnnuciation from Jesi. All generously loaned for exhibition at the Scuderie del Quirinale. With the announcement of Italy’s entry into the war, works from the Veneto also arrived at the Rocca, particularly from the Gallerie dell’Accademia and the Ca’ d’Oro. Requests for shelter for works of art multiplied, from all over the peninsula: the fortress of Sassocorvaro was then joined in April 1943 by the palace of the Falconieri princes in Carpegna. They arrived here masterpieces from Rome, Milan, Venice.

After the armistice in September 1943, the situation became more complicated, not least because of the missions of the Kunstschutz, the German agency responsible for unearthing works hidden during armed conflicts. Following the search by German soldiers in Carpegna in October 1943 (they opened only one crate containing Rossini’s scores; Rotondi had providently removed the tags from the other crates), the superintendent decided to return the crates to Urbino, to the basement of the Ducal Palace: it is reported that smaller, more valuable works such as Giorgione ’s Tempest or Mantegna ’s St. George were loaded directly into the car and hidden on the estate where Rotondi and his wife Zea Bernardini, also an art historian, spent the autumn, storing them in the bedroom. A curiosity that is certainly not found in history books, and which the exhibition instead has the merit of recounting and making known to the public. Important to this more intimate aspect were the pages of diaries and letters left by the superintendents themselves, which narrate the vicissitudes but above all the feelings and thoughts that were going through their minds at this juncture. The last section of the second floor of the exhibition is dedicated to the figure of Emilio Lavagnino, a retired Superintendency of Rome official who in January 1944 directed the expedition aimed at emptying the Marches warehouses to lead hundreds of crates within the neutral walls of the Vatican, driving at night with headlights off in his Topolino. Operation made possible by Giulio Carlo Argan, another key figure in the rescue of the works, who obtained permission from Cardinal Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, to keep the works in the Vatican. Lavagnino had also already accomplished the census and safeguarding of Lazio’s treasures, convincing bishops, parish priests and mayors to hand over the works to be sheltered in the Vatican. Among these works, four paintings by Antoniazzo Romano, now kept between Rieti and Sutri, and a work by Cristoforo Scacco from Fondi Cathedral were loaned to the exhibition. Note how the layout is often reminiscent of the wood of the crates within which the works of art were transported.

Moving up to the second floor of the exhibition, sections five through eight share similar titles, illustrating the situation in different Italian cities (Milan, Venice, Turin; Rome; Florence and Bologna; Genoa, Naples and Palermo) since the closure of the museums in 1940, and presenting the key figures who rose to prominence in the preservation of the artistic heritage. In her essay illustrating the fundamental contribution of art historians during the years of the conflict, who wrote diaries or small pamphlets “in which they recounted, sometimes day by day, sometimes in summaries, through a selection of the most striking actions, the transits of paintings, statues, frames, chandeliers, books, papers, from one depository to another, passing through checkpoints, bombings, torrential rains, with makeshift means that were never suitable and sometimes dangerous”, curator Raffaella Morselli recalls that on June 5, 1940, Minister Bottai ordered the implementation of all measures established for the protection of the movable artistic heritage, and especially the closure to the public of all museums, galleries and art collections until otherwise disposed. And it is for these works and these museums that it is necessary to remember figures such as Fernanda Wittgens, Vittorio Moschini, Noemi Gabrielli, Aldo de Rinaldis, Palma Bucarelli, Francesco Arcangeli, Antonio Morassi, Orlando Grosso, Bruno Molajoli, and Jole Bovio Marconi: men and women who committed themselves with their own strength, and sometimes even risking their own lives, in saving the monumental and artistic heritage of cities and entire territories. The catalog devotes ample space to their biographies to give a complete picture of their roles and courageous decisions. On the other hand, some of the works that were able to be saved thanks to their actions are visible in the exhibition, broken down by individual cities: just by way of example, and to mention the most important ones, we see Francesco Hayez’s Portrait of Alessandro Manzoni, Gaetano Previati’s Madonna of the Chrysanthemums , Tintoretto’s Portrait of Battista Morosini , Sebastiano Ricci’s Diana and Callisto, Francesco Francia’s Saint Stephen , Hans Holbein the Younger’s Portrait of Henry VIII, Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo’s Tobiolo and the Angel , and El Greco’sAdoration of the Shepherds and Baptism of Christ.

The exhibition draws to a close with a section devoted to an “incalculable damage to Italy as a whole, from which an incomparable heritage and a fundamental piece of its history was taken,” as Serena Di Nepi writes in her essay. She is referring to the raid that was carried out on the library of the Jewish Community of Rome in October 1943: here were preserved texts from the medieval and Renaissance periods, precious manuscripts, incunabula, the complete collection of Levantine Hebrew prints published between the fifth and seventeenth centuries in the Ottoman Empire, and much more. At the time of the raid, however, as Di Nepi explains, there was a lack of a catalog and a lack of accurate and up-to-date information on the qualitative and quantitative size of this collection. In 1948, thanks to the work of the Italian Restitution Mission directed by Rodolfo Siviero more than fifty cases were recovered from the Library of the Italian Rabbinical College, but of all those from the Community Library nothing has been heard since that October of 1943.

The closure of the exhibition is instead entrusted to the chapter on restitutions and recovery activities, starting with the Monuments Men, who still since 1943 have been engaged in saving the artistic-cultural heritage and in the restitution to the legitimate owners of the dispersed works of art, and ending with the figure of Rodolfo Siviero, appointed head of theInterministerial Office for the Recovery of Works of Art, as well as sent to direct the Italian diplomatic mission to the Allied Military Government in Germany. In 1947 he obtained the restitution of art goods stolen after September 8, 1943, and in 1948 the return of works purchased by Nazi hierarchs and illegally exported to Germany, such as the Lancellotti Disk. Exhibitions were also organized to celebrate the return of the artworks to Italy, including one in the halls of the Farnesina between 1947 and 1948 and those at Palazzo Venezia in 1948 and 1950. Among the works exhibited at the first Exhibition of Works of Art Recovered in Germany, held in 1947 at the Farnesina, was Titian’s Danae, which Hermann Göring (Hitler’s top lieutenant) had hung in his bedroom and which is now on display at the Scuderie del Quirinale as a symbolic work of those events.

This concludes an exhibition that the writer found informative and well-structured, which should be visited by as many people as possible, especially schools. Because this exhibition has the merit of bringing into play a dramatic moment in History, while accompanying its course through the eyes of those who did so much to fight against this terrible monster that is war and the destruction it brings with it. It has the merit of introducing aspects not found in history books and showing through archival photos how monuments and cities were protected in that past. Perhaps the topic of the penultimate section, that of the Jewish community’s book heritage, should have been developed more to reflect on the fact that the latter, contrary to Minister Bottai’s efforts to safeguard the works, was not saved and was therefore lost. With regard to the works, it was also noted that both the exhibition and the catalog lack a descriptive apparatus, but this is something that, in the writer’s opinion, does not jar with regard to this type of exhibition.

The exhibition aims (succeeding) to lead visitors into an important reflection on the protection of cultural property, a fundamental theme in the present because not taking care of monuments, works and artistic-cultural treasures all means not understanding their value, just as in the past, when the Second World War put them in serious danger and, if it had not been for the women and men who fought to protect them, what would be left of them today?

“What we have told here is a story of which Italy should be proud, which we hope to bring out in all its importance, and which should be considered a decisive step in the formation of the contemporary national consciousness of the protection of cultural heritage,” stressed Ales spa Scuderie del Quirinale president and CEO Mario De Simoni. “An achievement that we owe to the women and men we spoke about.” And to these goes all our gratitude.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.