by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 05/08/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'The Good Century of Sienese Painting,' in Montepulciano, San Quirico d'Orcia and Pienza through Sept. 30, 2017.

And so here we come to the good century of Sienese painting, and here are its most worthy masters. This formula, which Abbot Luigi Lanzi employs in his Storia pittorica d’Italia in order to introduce the chapter devoted to the most notable artists of the sixteenth century in Siena, could serve as a laconic but dense presentation of the exhibition on the Sienese sixteenth century which, in its title, borrows precisely Lanzi’s words: Il buon secolo della pittura senese. From the Modern Manner to Caravaggesque Enlightenment. An exhibition divided into three sections, in Montepulciano, San Quirico d’Orcia and Pienza, to retrace the history of painting in Siena and its environs, from the beginnings of Mannerism, with the young Domenico Beccafumi, to the Caravaggesque naturalism of Rustichino: in between, all the “most worthy masters” who allowed Siena to experience one of the most artistically lively and fruitful seasons of its history, even if little known to the general public. Not the easiest operation and, if you will, also somewhat laborious, as is any exhibition that unravels across several venues and is notably animated by a research project far from easy clamor, but certainly decidedly intriguing. In fact, there are many reasons to consider the Sienese exhibition an authentic gem: first of all, it is an exhibition that presents the public with important new discoveries, some of which concern the fundamental figure of Domenico Beccafumi (real name Domenico di Giacomo di Pace, Sovicille, circa 1484 - Siena, 1551). Again, the exhibition attempts to untie the knot concerning one of Sodoma’s most talented pupils, that unidentified “Marco Bigio” author of some works now wanted to be assigned to Girolamo Magagni, better known as “Giomo del Sodoma.” Then, the exhibition is an opportunity to observe some interesting unpublished works, among which a splendid, refined Visitation by Rustichino stands out.

However, beyond the aspects that are perhaps more suited to an audience of specialists, or to those with a strong passion for Sienese painting, it is also necessary to highlight other themes that The Good Century of Sienese Painting intends to present. One above all: the exhibition is inextricably linked to its territory. This is one of the topics of the current debate around exhibitions: too often, in our cities, pre-packaged exhibitions swoop in that not only have nothing to do with the territory that hosts them, but also do not even bother to seek even tenuous ties, or at least to collaborate with the cultural institutions of the host city. The Montepulciano, San Quirico d’Orcia and Pienza exhibition, on the other hand, is strongly rooted in its land: if desired, the exhibition’s itinerary continues outside its three venues. This is an aspect on which the curators have greatly insisted: in each of the three venues, the visitor will find suggestions that will enable him to discover other works, complementary to the discourse begun in the exhibition, scattered in the museums, churches, monasteries and palaces of the area. The visitor will also be able to benefit from a well-curated informative project, capable of providing everyone with a clear introduction to the problems of Sienese painting in the sixteenth century. And it is necessary to reiterate how the itinerary leaves great freedom to the public. As much as the natural consecution of the topics suggests starting from Montepulciano and then going to San Quirico d’Orcia and finally to Pienza, there are no problems in taking the reverse route (exactly as the writer has done), or in choosing a different starting point than the more “logical” one, and then carving out spaces of maneuver consonant with one’s own inclinations.

|

|

Exhibition The Good Century of Sienese Painting: the Montepulciano section |

|

|

Exhibition The good century of Sienese painting: the section of San Quirico d’Orcia |

The narrative can therefore start from the Montepulciano section(Domenico Beccafumi, the artist as a young man), set up at the Museo Civico Crociani and curated by Alessandro Angelini and Roberto Longi. Although this is probably the most interesting section, in terms of the quantity of novelties proposed by the curators and the quality of the works exhibited, it is perhaps, at the same time, also the one with the least successful organization: the setting up of the exhibition not in a reserved exhibition space, but in a room of the museum that houses a considerable part of the picture gallery, and the confusion that certain choices may generate in the visitor (such as starting the exhibition from the room dedicated to the so-called “Caravaggio of Montepulciano,” with apparatuses that are moreover similar to those of the permanent collection) do not depose in favor of the project. However, these are details that, it is safe to say, are overshadowed by the exceptional nature of the exhibition, which opens immediately with the new discovery that redraws Domenico Beccafumi’s early activity. The first work is in fact a St. Agnes that has had alternating attributional vicissitudes (at one point in its history it was even thought to be an 18th-century copy of a 16th-century original): these originated above all, as Alessandro Angelini explains in the catalog, “from the insistently sacral, as it were timeless, aspect with which the Polizian saint is depicted, almost with the desire to re-propose with that rigid frontality an older cult image of the city’s patron saint.” The turning point came precisely on the occasion of the exhibition: the scholar Andrea Giorgi discovered a document from 1507 in which Lorenzo Beccafumi, a banker who later became podestà of Montepulciano, and above all the “discoverer” of Domenico’s talent (so much so that the artist, welcomed under the protective wing of the landowner, would take his surname in homage to him), assigned the painter the realization of a “figure of Sancta Agnese” for the municipality. This is an important piece of evidence, which has made it possible to uncover what is now considered the artist’s earliest documented work, and which also finds stylistic parallels in the painting’s essentially Perugian setting, in accordance with Vasari’s assertions in his Lives. It should also be noted how, until now, Vasari’s report of Perugino ’s influence on Beccafumi could not be verified through secure works on a documentary basis: the first certainties about the Sienese painter’s art, in fact, start from a period of five years after the execution of the Sant’Agnese, that is, when the artist was already beginning to experiment with new possibilities.

Around the Sant’Agnese unravels the plot of Domenico Beccafumi’searly activity. The second part of the exhibition therefore opens with the works of some of the masters who worked in Siena at the beginning of the sixteenth century (we have Girolamo del Pacchia, and above all the elegant Allegory of Heavenly Love by Sodoma, one of the most famous and valuable paintings in the entire exhibition: less specifically, we observe a set of panels that demonstrates how strong, at the time, was the dependence of Sienese painting on typically Umbrian modes) and continues with a reconstruction of Domenico Beccafumi’s career up to about 1515. It begins with the three Heroines of Antiquity, a Judith, an Artemisia and a Cleopatra, which constitute as much “one of the oldest attestations of the triad with heroines extolling the fidelity of marriage, so widespread in painting in Siena in the first half of the sixteenth century,” as Angelini explains in the catalog, as well as one of the earliest evidence of Beccafumi’s art: they are in fact referable to a period close to the execution of the Sant’Agnese, although there is a certain stylistic gap between the more awkward Judith (which should therefore be earlier) and the more fluid Artemisia and Cleopatra.

In the latter two the first Raphaelesque suggestions would seem to become apparent: the exhibition gives us a way to follow the development of Beccafumi’s reflections on Raphael (and not only) by offering us, in the meantime, a Madonna and Child with St. John, from a private collection, of nineteenth-century attribution to the Sienese painter. Domenico Beccafumi, in 1508, had sojourned in Florence, and this painting may be an early result of his study of Raphael’s art, evident not only in the painting’s crystalline clarity, but even in its treatment of the affects, and also in its proximity to Leonardo da Vinci: indeed, the composition picks up some motifs from Leonardo’s Madonna dei Fusi. In the work, and in particular in the landscape that can be seen behind the protagonists, the influence of the art of Fra Bartolomeo is also discernible, of such importance that it led to the Florentine artist’s Rest during the Flight into Egypt being brought to Montepulciano (from Pienza). A continuous crescendo, which also passes through mythological subjects (exhibited is a Venus with two cupids from about 1513), leads to the Madonna and Child of about 1514, kept at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena: it is a work that, although fragmentary (the background and the mantle on the right were repainted later), certifies Domenico Beccafumi’s now achieved maturity. As Roberto Longi points out, even a quick glance at the Virgin’s face would be enough to notice: “thin layers spread in veils create effects of transparency, allowing a glimpse of the underlying blond hair, while strokes of fuller white reveal the folds of the very light fabric embellished by the insertion of double gold fillets, just as with gold the sparse, but brightly shining, curls of the head of the little Redeemer are detected.”

|

|

Domenico Beccafumi, Saint Agnes of Montepulciano (1507; oil on canvas, 163 x 123 cm; Montepulciano, Museo Civico Pinacoteca Crociani) |

|

|

Girolamo del Pacchia, Madonna and Child, St. John and Two Angels (1505-1510; tempera grassa on panel, 55.8 x 42.2 cm; Siena, Private Collection) |

|

|

Giovanni Antonio Bazzi known as Sodoma, Allegory of Heavenly Love (c. 1504; oil on panel, 96 x 49.5 cm; Siena, Chigi Saracini Collection, Property of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena) |

|

|

Domenico Beccafumi, The Three Heroines of Antiquity: Judith, Artemisia, Cleopatra (c. 1506; oil on panel, 77 x 44.7, 77.1 x 43.5, and 77 x 44 cm, respectively; Siena, Chigi Saracini Collection, Property of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena) |

|

|

Domenico Beccafumi, Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist (c. 1508; oil on panel, 72 x 58 cm; Florence, Private Collection) |

|

|

Fra’ Bartolomeo, Rest during the Flight into Egypt (1505-1506; tempera grassa on canvas, 135 x 113.5 cm; Pienza, Museo Diocesano) |

|

|

Domenico Beccafumi, Madonna and Child (c. 1514; oil on panel, 60 x 45.5 cm; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

The San Quirico d’Orcia section(From Sodom to Hedgehog: Sienese Painting in the Last Decades of the Republic, curated by Gabriele Fattorini and Laura Martini), characterized by a much more linear layout and taking place in the rooms of Palazzo Chigi Zondadari, is an overview of Sienese art in the first half of the 16th century: a short but complex section, consisting of some 30 works and opening with a new, dense comparison between Sodoma and Domenico Beccafumi, which also takes on the role of questioning (should there have been a need, given that Sodoma’s work has now been fully reevaluated) Vasari’s judgment: the Aretine had in fact compared the two artists only to have the latter come out the winner. In Vasari’s account it almost seems as if the Piedmontese Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, who went down in history by the nickname of Sodoma (Vercelli, 1477 - Siena, 1549), had moved to Volterra in order to escape comparison with his younger rival, but in reality it was not out of necessity that the artist left his adopted city. From the juxtaposition emerge the original, independent and profoundly different personalities of two supreme artists who marked the art of the time: we therefore have the opportunity to admire two Cristi portacroce by Domenico Beccafumi, one of which was made with the participation of the workshop, referable to two different moments of his career (the one with the workshop around 1520, the other painted around 1545), and the coffin heads that Sodoma painted between 1526 and 1527 for the company of San Giovanni Battista della Morte in Siena. This particular type of object, which abounds in Sienese art of the period (the Montepulciano section also includes two pairs of paintings by Beccafumi made for identical purposes), was intended to decorate the biers of the deceased that were used to carry coffins during funerals. In particular, in the panel of the Madonna and Child, Sodoma produces, as Enzo Carli noted, one of the best interpretations of Raphael’s art, but in general the whole is marked by anintensity and a participatory rendering of feelings (note the body and the expression of Christ in pity) that are hardly matched, so much so that they have merited the open praise of Vasari, who even defined this group of panels as the “most beautiful work in Siena.” Turning our gaze in the opposite direction we will encounter Beccafumi’s Christ Carrying the Cross: a work that is also interesting for the fact that the artist tries his hand at an iconographic theme of Lombard matrix, particularly practiced by Sodoma (who also tackled it in the frescoes of Monteoliveto Maggiore), and which is resolved by the Sienese artist with a pose and expression that denote great suffering, with the figure of Christ connoted by Michelangelo-like anatomies and modern chiaroscuro effects, and with the 1545 version characterized by a very rapid and loose brushstroke.

The first room, which serves as an introduction and offers a roundup of works painted by artists active in Siena in the first decades of the 16th century, is followed by one that focuses on the extreme stages of Sodom’s career. These are mostly works intended for private devotion and of traditional iconography, which the artist is nevertheless able to render with great refinement and intimism: observe, by the way, the Holy Family with St. John of the Crociani Museum in Montepulciano, a work that presents us with a Virgin of rare beauty, of Raphaelesque matrix, who presents, like the other figures, that “turgid, compact modeling , almost enameled” of which Laura Martini speaks in the catalog entry, showing the hair highlighted by the marvelous threadlike golden highlights typical of the artist, and distinguished by her “turned and polished” face also discernible in other coeval realizations. And it is also to such realizations that he had to look at that “Marco Bigio” mentioned above, whom Gabriele Fattorini suggests, in a seven-page essay, to identify with Giomo del Sodoma on the basis of stylistic comparisons. A pupil of Sodoma, Giomo-Marco is a painter unknown to most, and yet capable of articulating skillful and cultured compositions: this is the case, for example, of Venus, a painting with a complex iconography that is difficult to summarize in a few lines. Leonardoesque reminiscences and Nordic, Dürerian suggestions characterize this work as much as Montalcino’s Christ in Pity, restored for the occasion and displayed in the center of the room: a work that on the one hand openly refers to the Madonna del Corvo frescoed in Siena by Sodoma, reinterpreting the Vercelli painter “in eccentric forms,” as Gabriele Fattorini explains, “with a personal predilection for contrasts of light and for a sharp, metallic character of the physiognomies,” and on the other hand takes its cues from Leonardo models, as denounced by the face of Saint John.

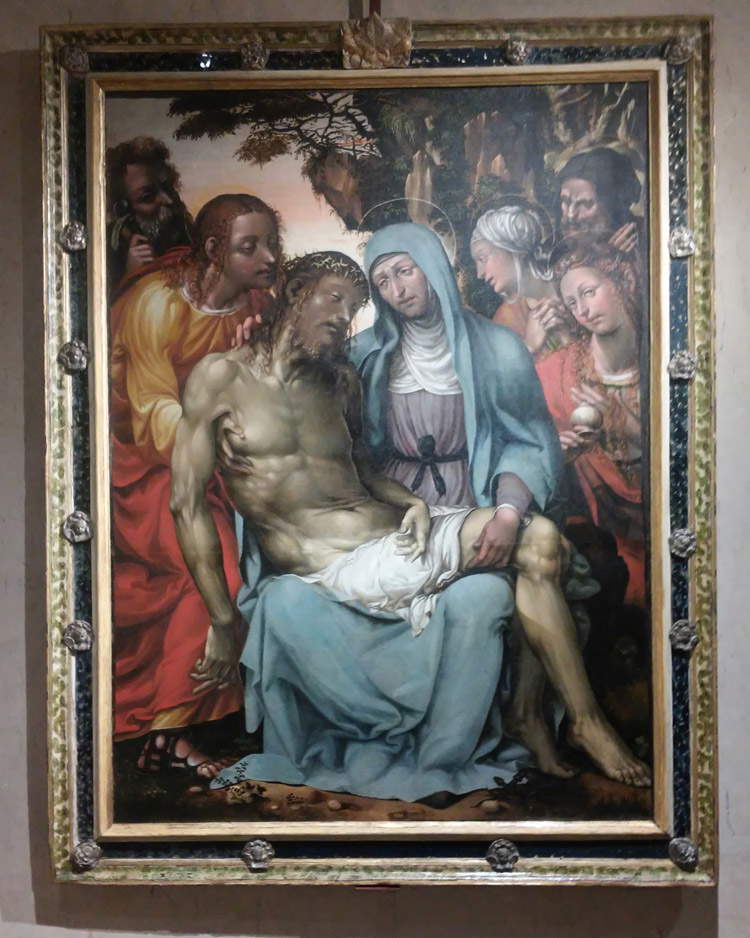

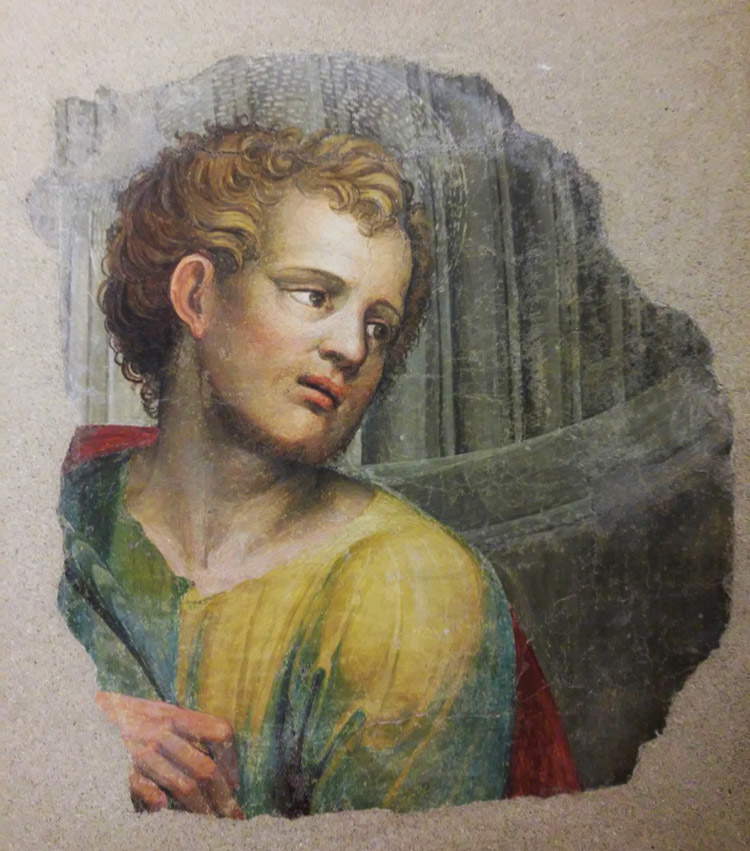

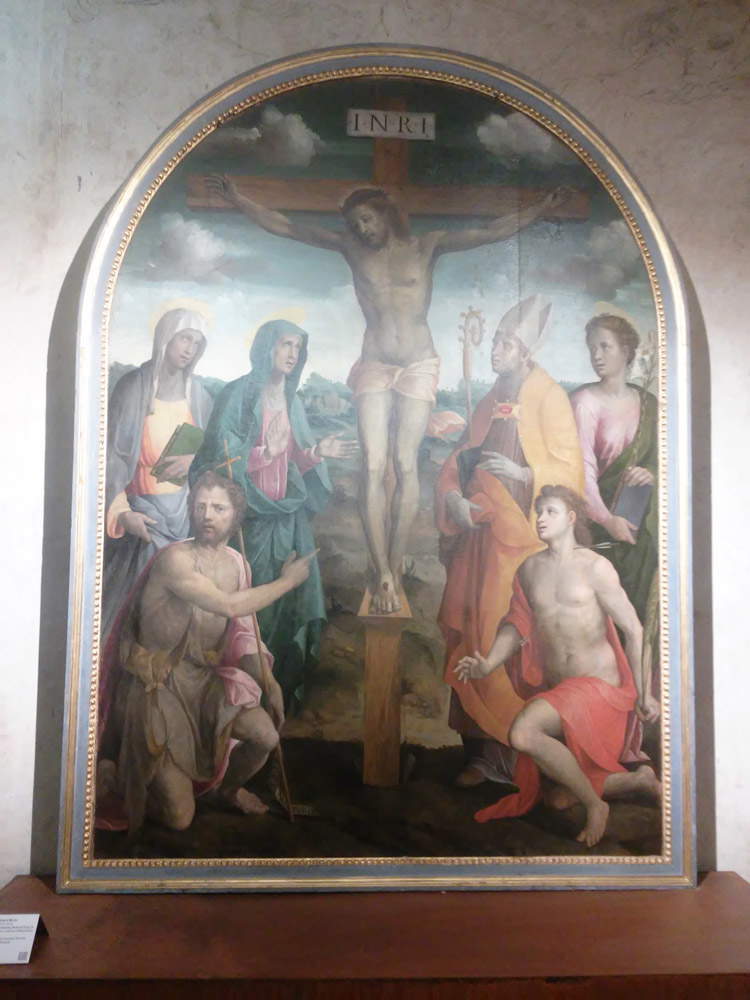

Closing the San Quirico section is the room devoted to the artist to whom the primacy of Sienese art in the middle of the century belonged, once Sodoma and Beccafumi had disappeared: Bartolomeo Neroni, known as the Riccio (Siena, documented from 1531 to 1571). A pupil of Sodoma (who later became his father-in-law) and an eclectic artist, he saw the end of the Republic of Siena, which fell in 1559, ending up incorporated into the Duchy of Florence to which it had definitively surrendered; he left his hometown to repair to Lucca and returned only at the end of his career: we appreciate his progress from his beginnings under the banner of a classicism indebted to the art of Baldassarre Peruzzi, and witnessed in the exhibition by the fragments of the frescoes in Siena Cathedral, to complex works such as the majestic Lucignano altarpiece, which achieves surprising results of monumentality, or the San Quirico altarpiece, in which Riccio meditates on Sodoma, Raphael (note the baldachin, mindful of solutions by the Florentine Raphael) and Friar Bartholomew (from him he derives the setting of the composition), and finally arriving at the compassed and devout works of the final phase of his career, which denote a certain stylistic regression and a retreat to more rigid forms.

|

|

Comparison of Sodom (foreground) and Beccafumi |

|

|

Giovanni Antonio Bazzi known as Sodoma, Head of Coffin for San Giovanni Battista della Morte, panel with Madonna and Child (1526-1527; oil on panel, 63 x 42 cm; Siena, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

|

|

Left: Domenico Beccafumi and workshop, Christ Carrying the Cross (c. 1520; oil on panel, 73.5 x 51 cm; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale). Right: Domenico Beccafumi, Christ Carrying the Cross (c. 1545; oil on panel, 80.3 x 60.5 cm; Siena, Museo Diocesano) |

|

|

Giovanni Antonio Bazzi known as Sodoma, Holy Family with St. Giovannino (c. 1540; oil on panel, 70 x 47 cm; Montepulciano, Museo Civico Pinacoteca Crociani) |

|

|

“Marco Bigio” (Giomo del Sodoma?), Venus or The Three Ages of Woman (c. 1540-1545; oil on canvas, 229 x 169 cm; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

|

“Marco Bigio” (Giomo del Sodoma?), Christ in Pity (1535-1540; tempera/oil on canvas, 191 x 149 cm; Montalcino, Sant’Egidio) |

|

|

Bartolomeo Neroni called the Hedgehog, fragments of frescoes for Siena Cathedral, from top, counterclockwise: Martyrdom of the Four Crowned Saints; Madonna and Child, Two Martyr Saints and Two Angels; Martyr Saint (1534-1535; frescoes detached and transported on fiberglass support, 75 x 125, 104 x 32 and 59 x 54 cm; Siena, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

|

|

Bartolomeo Neroni known as Riccio, fragments of frescoes for Siena Cathedral, detail of the martyr saint |

|

|

Bartolomeo Neroni known as Riccio, Lucignano Altarpiece: Crucifixion and Saints John the Baptist, Mary of Cleophas, Mary, Sebastian, Augustine, Catherine of Alexandria (1540-1545; oil on panel, 220 x 160 cm; Lucignano d’Arbia, San Giovanni Battista) |

|

|

Bartolomeo Neroni known as Riccio, San Quirico d’Orcia Altarpiece: Madonna and Child with Saints Sebastian, John, Quirico and Leonard (1545-1550; oil on panel, 270 x 195 cm; San Quirico d’Orcia, Compagnia del Santissimo Sacramento della Pia Associazione di Misericordia) |

The exhibition skips the second half of the sixteenth century (that, to be clear, of artists such as Francesco Vanni, Ventura Salimbeni, and Alessandro Casolani) to move to the end of the century, when the inspiration of Francesco Rustici was developing, in the wake of the achievements of the masters who had preceded him, known as il Rustichino (Siena, 1592 - 1626), a painter to whom the third and last section of the exhibition is dedicated, that of Pienza, set up in the premises of the Conservatorio San Carlo Borromeo(Francesco Rustici detto il Rustichino, caravaggesco e gentile, curated by Marco Ciampolini and Roggero Roggeri). Rustichino was the leading artist of the early seventeenth century in Siena, a time when he held the primacy of art in the city, sharing it with Rutilio Manetti (Siena, 1571 - 1636): a painter with a short but intense parabola, he proposed a Caravaggism mediated by tradition to elaborate a style that, in the words of Marco Ciampolini, was “capable of manifesting in an intimate and profound way the most authentic essence of Sienese painting” and “succeeded in innovating tradition from within, without apparent upheaval but in such a radical way that after him nothing would ever be the same.” The start is delegated to the context within which Rustichino’s training took place: the exhibition thus allows us to familiarize ourselves with artists such as the aforementioned Alessandro Casolani, whose Sacra Famiglia con san Giovannino e santa Caterina (Holy Family with St. John and St. Catherine) is exhibited, as gentle and soft as the characters that populate the Sant’Ansano che battetezza una bambina (St. Ansanus baptizing a little girl ) by Vincenzo Rustici, Francesco’s father and Casolani’s brother-in-law, whose collaborator he was and whose various stylistic solutions he took up, as the painting attests. This is the strictest Sienese tradition within which Rustichino would always have moved, but there are also other models: in 1615 the artist in fact made a sojourn in Rome where he came into contact with Caravaggesque circles. Prominent in the exhibition are a Madonna and Child by Orazio Gentileschi, related to the Annunciations of San Siro in Genoa and Turin, and an Allegory of Purity recently attributed to Antiveduto Gramatica (a painter Rustichino frequented for some time) and recently “discovered”: its only appearance in a scholarly publication dates back to 2015.

Thus begins a four-room itinerary that leads the visitor into the meanderings of Rustichino’s art, with a stage that explores the context of painting of his contemporaries (with works by Rutilio Manetti, Bernardino Mei, Niccolò Tornioli and others). An itinerary that can begin with an unpublished St. John the Baptist, the work of a Rustichino at the beginning of his career who, while not moving away from the lesson of Vincenzo Rustici and Alessandro Casolani, already demonstrates his own sensitivity, thanks to which a vivacity unknown to his father and uncle creeps into the works: that of Rustichino is a "suggestive pictoricism that flows into pleasant landscapes illuminated by a white, almost lunar light, according to the modes proposed by Paul Brill, which had found such a welcome in the late Mannerist culture of Siena. A spontaneity equal to that of the Baptist is discernible in the Visitation, another unpublished work (mentioned in the opening), still reminiscent of late Sienese Mannerism: delicate faces, measured composition, draperies that recall that Baroque lesson that made such a splash in the city and was among the reasons for the major exhibition that Siena dedicated in 2009 to Federico Barocci and his influence on local artists. We follow Rustichino’s progress to a point where his “gentle Caravaggism” has now fully unfolded: the last work in the exhibition (which concludes the itinerary as it is still located in its original location, that is, the high altar of the church of San Carlo Borromeo, integrated into the museum itinerary), a Madonna and Child with Saints, demonstrates the first openings toward Caravaggio’s naturalism, evident in the features, poses and looks of the characters (as well as, of course, in the study of light and shadow), leading to the incredible results of a work such as the Dying Magdalene, which undoubtedly looks to Gerrit van Honthorst.

|

|

Alessandro Casolani, Holy Family with St. John (1596; oil on canvas, 116 x 88 cm; Siena, Chigi Saracini Collection, Property of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena) |

|

|

Vincenzo Rustici, Saint Ansano baptizing a little girl (c. 1585; oil on canvas, 99.5 x 99.5 cm; Siena, Monte dei Paschi Foundation) |

|

|

Orazio Gentileschi, Madonna and Child (c. 1613-1620; oil on canvas, 139.8 x 98 cm; Private collection) |

|

|

Antiveduto Gramatica, Allegory of Purity (oil on canvas, 74 x 59 cm; Private Collection) |

|

|

Francesco Rustici known as Rustichino, Saint John the Baptist (c. 1600-1605; oil on canvas, 138 x 106.5 cm; Florence, Massimo Vezzosi Collection) |

|

|

Francesco Rustici known as Rustichino, Visitation (c. 1600-1605; oil on canvas, 142 x 101 cm; Private Collection) |

|

|

Francesco Rustici known as Rustichino, Maddalena Morente (c. 1625; oil on canvas, 148.5 x 219 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

|

Francesco Rustici known as Rustichino, Madonna and Child with Saints Charles Borromeo, Francis, Clare, Catherine of Siena and John the Baptist (1622-1623; oil on canvas, 296 x 207 cm; Pienza, San Carlo Borromeo) |

After such an exhibition, taking a day or two to visit the places where it takes place is an activity that becomes almost natural and indispensable: precisely because The Good Century of Sienese Painting is an open exhibition, involving the territory (from which, moreover, the vast majority of the loans come) and extending its discourse to whatever else can be observed in the villages of this placid portion of Tuscany. The operation is promoted with full marks and The Good Century of Sienese Painting could almost be indicated, with an Anglicism that is particularly in vogue today, as a best practice, attentive, non-invasive and intelligent: a timely, serious and high quality research exhibition that speaks to both the specialist and the enthusiast, and whose attempt (in many ways successful) to open itself up to the general public should be appreciated, despite the fact that it certainly cannot be called a box-office exhibition. A note, finally, on the superlative catalog, published by Pacini: full of information, long, exhaustive, well-detailed entries, and essays that open up new scenarios, it has already become an indispensable tool for anyone wishing to study 16th-century Sienese painting.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.