by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 02/04/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Genovesino and Piacenza,' in Piacenza, Palazzo Galli, March 4 to June 10, 2018.

The Genovesino and Piacenza exhibition that recently opened in the rooms of Palazzo Galli, a valuable exhibition venue of the Banca di Piacenza, is more than just an appendix born on the heels of the success of the successful monographic exhibition in Cremona, the first ever dedicated to Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino (Genoa?, circa 1605-1610 - Cremona, 1656). In spite of the small number of works present (about twenty, in two rooms), the Piacenza exhibition stands out as an exhibition with its own autonomy, and aimed at shedding light on at least three main topics. The first concerns the presence of Genovesino in Piacenza: a presence about which, in truth, very little is known, with the aggravating circumstance that no works are known that can be referred with certainty to the period that the painter spent in Emilia. The second is the persistence of relations with Piacenza after Genovesino’s move to Cremona, which decreed the painter’s success. The third is instead the link between painting and engraving in the production of the artist of Ligurian origin, but Lombard by adoption: a relationship that the Cremona exhibition had indeed framed, notably in the catalog, but without going into too much detail with precise comparisons between paintings and prints, as happens in the Palazzo Galli exhibition. All the prerequisites are therefore in place for a small research exhibition, animated by a project aimed at clarifying one of the most obscure points in Genovesino’s career and, thanks to the contribution ofsome interesting new developments, at laying the foundations for future research on some important aspects of his production.

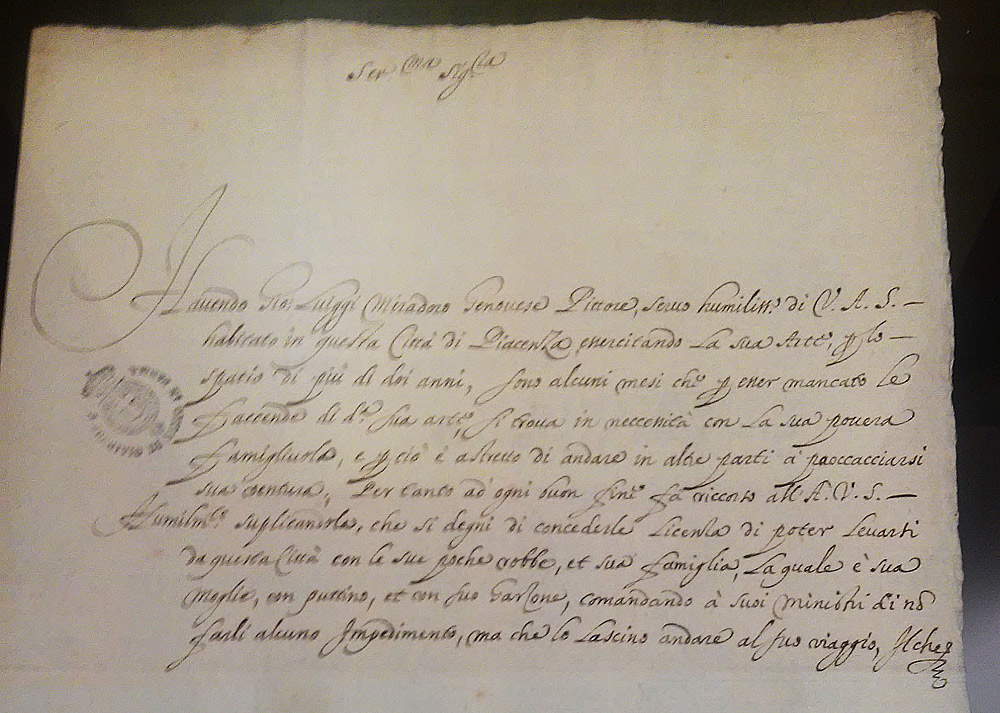

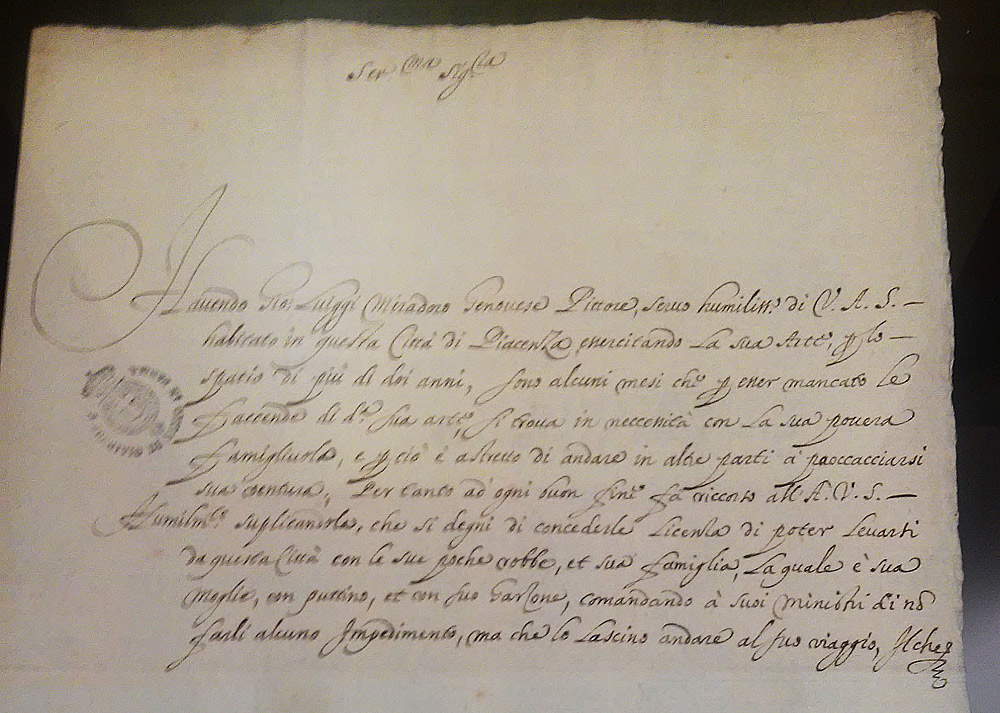

The curators, the same as those of the Cremonese exhibition(Francesco Frangi, Valerio Guazzoni and Marco Tanzi), offer clear indications about the title chosen for the review: not Genovesino in Piacenza, but Genovesino and Piacenza, because “the conjunction,” they write in the catalog, “immediately suggests that the reflections on the painter’s relationship with the Emilian city cannot be focused on the short time of his stay,” and this for the two reasons mentioned above, namely because too little information is available about Luigi Miradori’s actual presence in Piacenza, and because his relationship with the city continued even after his move to Lombardy. The period he spent in Piacenza can be roughly placed between 1632 and 1635: to fix it with relative certainty it would help to have some documents, which attest to the birth of his three children (Giovanni Giacomo in 1632, Angela Nicoletta in 1634 and Giovanni Battista in 1635: the last two, however, survived only a few days), the disappearance of his wife Girolama and his subsequent marriage to Anna Maria Ferrari, and the plea to the duchess of Parma and Piacenza, Margherita de’ Medici, in which the painter asks the lady to allow him to leave the city to seek his fortune elsewhere. This is a very touching document, moreover on display in the exhibition: the painter, at the height of his despair, stating that “he finds himself in need with his poor little family, and in order to do so he is obliged to go to other parts to seek his fortune,” asks the duchess for “permission to be able to leave this city with his few belongings, et his family, which is his wife, a cherub and one of his Garzones, commanding his ministers not to make any impediment for him, but to let him go on his journey.” Thanks to this document, dated September 1635, it was possible to have confirmation on the length of Genovesino’s stay in Piacenza, since the artist, in the letter, declared that he had been in the city for “more than doi years.” Other sources help to reconstruct a partial picture of the Piacenza sojourn: we know, in particular, that some of the artist’s works were located in some of the city’s churches, but are now lost. We can then hypothesize that the artist chose to move to Piacenza, as Laura Bonfanti recalls in her catalog essay entirely devoted to the relationship between Genovesino and the city, because he was called there by one of his fellow citizens, the man of letters Bernardo Morando (Sestri Ponente, 1589 - Piacenza, 1656), who had been residing in Piacenza since 1604 and who worked at the Farnese court as director of theatrical performances, stage designer and poet. At present, however, not much else is known.

|

| A room of the Genovesino and Piacenza exhibition |

|

| A room from the Genovesino and Piacenza exhibition |

|

| A room from the Genovesino and Piacenza exhibition |

|

| The supplication to Margherita de’ Medici |

The room that opens the exhibition offers a quick survey of what, at the current state of knowledge, are Genovesino’s earliest known paintings: on display are works that already figured in the Cremona exhibition, such as the Holy Family from the Gazzola Institute (the painter’s first dated work: 1639), the Caravaggio-esque Lute Player formerly assigned by Roberto Longhi to Orazio Gentileschi and later referred by him to Luigi Miradori almost forty years after the first attribution, and theAdoration of the Magi from the National Gallery in Parma. This first overview, in addition to providing visitors with some important elements to begin to familiarize themselves with the painter’s style (fascinated by Caravaggio, dense with Genoese memories from Bernardo Strozzi to Anton van Dyck, with one eye looking to the Milan of Morazzone and the other attentive instead to the sixteenth-century Emilia of Correggio and the seventeenth-century Emilia of Guercino), also offers the possibility to begin to investigate the artist’s relations with Piacenza. In particular, for the Holy Family the identification with a homologous work that in 1693 was in the home of a Piacenza priest, Giambattista Riccardi, has been hypothesized, and this circumstance would suggest that the painting was made for an ancestor of his who was in contact with Genovesino: it would be, in the case, one of the many works that the artist made from Cremona for Piacenza (a city from which, moreover, the Holy Family has never moved: recorded with certainty in the collection of another Piacenza family, the Martellis, it was donated by them in 1838 to the Gazzola Institute, where it is still preserved). More tenuous, on the other hand, are the connections for the large Adoration of the Magi, whose ancient history is currently unknown: however, the fact that a copy of it can be found in the parish church of Albarola, a village in the province of Piacenza, might suggest that the painting was executed for a Piacenza location.

Alongside the three works mentioned above, the first room presents visitors with two paintings that were not on display in the Cremonese exhibition, however. The first is a Circumcision of relatively small format, but distinguished by monumental breath and scenographic taste: in fact, the scene finds space under a large classical archway, beyond which an imposing cult building can be glimpsed, also classical in style, and is configured, according to Marco Tanzi, as “the first attempt to frame the sacred episode in an articulate and majestic perspective setting, strongly allusive.” It is a work dated 1643 (the date is conspicuously affixed to the base of the altar above which Jesus is undergoing the rite of circumcision), but whose known history has always been linked to Piacenza, since it was first presented to the public in the city in 1926 and was held in a Piacenza collection at the time. The second is a Portrait of a Gentleman, owned by the Cavallini-Sgarbi Foundation, and on whose attribution, however, there are different positions: the work of Genovesino according to Marco Tanzi, who found the similarity between the effigy and the offerer Martino Rota who appears in the altarpiece with Saint Nicholas of Bari, dated 1654 and now in the Brera Art Gallery, while it would be painted by Cristoforo Savolini (Cesena, 1639 - Pesaro, 1677) in the opinion of Massimo Pulini.

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Holy Family (1639; canvas, 182 x 134 cm; Piacenza, Fondazione Istituto Gazzola) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Lute Player (canvas, 138 x 100 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova, Palazzo Rosso) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Adoration of the Magi (canvas, 240 x 178 cm; Parma, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Circumcision (1643; canvas, 142 x 107 cm; private collection) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Portrait of a Gentleman (1639; canvas, 91.5 x 67 cm; Ro Ferrarese, Cavallini-Sgarbi Foundation) |

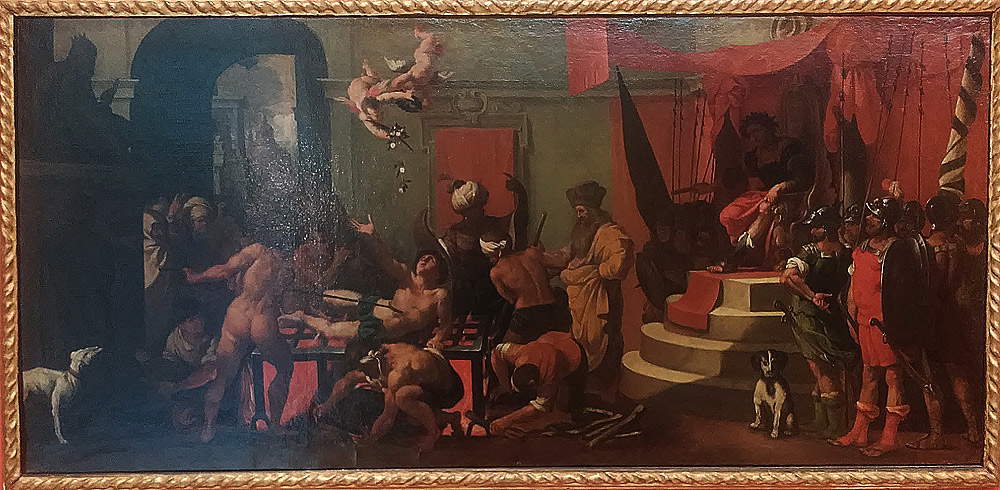

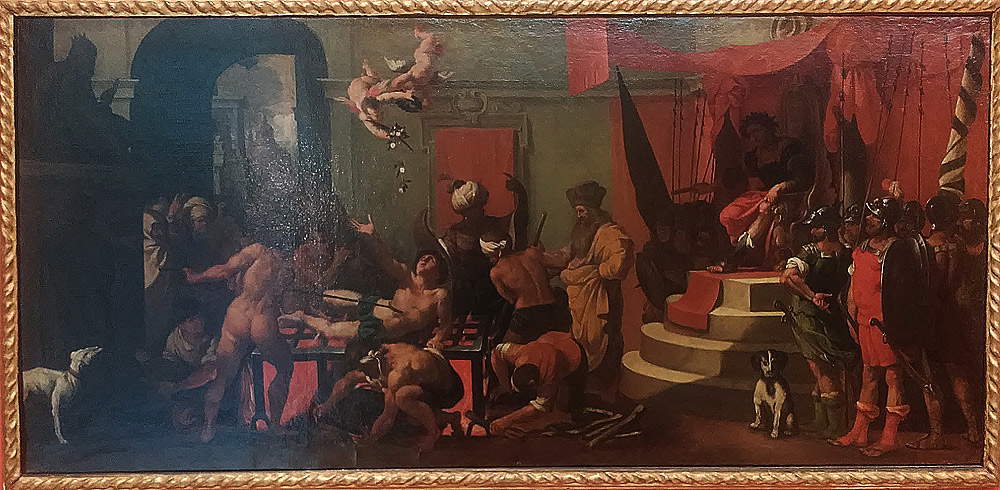

To find a painting that, albeit entirely hypothetically, could be assigned to the Piacenza sojourn, we have to wait until the second and last room, where the canvas, also already at the Cremona monograph, depicting the Punishment of Core, Dathan and Abiram (although doubts remain around the subject), the three characters from the book of Numbers who, for rebelling against the authority of Moses and Aaron, had suffered divine punishment, is on display. The first mention of the painting, which was then in the Piacenza collection of Marquis Francesco Serafini (albeit with attribution to Morazzone), dates back to 1734, while for the reference to Genovesino it is necessary to wait until 1939 with Armando Ottaviano Quintavalle: the stylistic proximity to coeval works in the Genoese sphere (one wanted to relate the small canvas to the achievements of Gioacchino Assereto), and the ancient attestation at a Piacenza collection, which would suggest that the work was in ancient times intended for the city, are the only, shaky footholds for a hypothetical reference to the years between 1632 and 1635. After passing the great Beheading of St. Paul, with which Genovesino takes up, revisiting it (and stating it directly on the painting: a bizarre and unusual fact), an invention of Guercino’s (it is the lost Martyrdom of St. James the Greater, made for the cathedral of Reggio Emilia and known only from an engraving by Giovanni Battista Pasqualini, featured in the exhibition next to Luigi Miradori’s painting), we encounter a pair of canvases from a private collection, the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence and the Massacre of the Innocents, published in 1989 by Ferdinando Arisi, a great art historian from Piacenza: a pair of inscriptions on the back inform us that the works are to be dated to 1643 and were made for an “Ill. S. Presidente Rosa / Piacenza,” identified by Marco Tanzi as the aristocrat Pier Maria Dalla Rosa, who at the time the painting was executed held the post of president of the Camera Ducale di Piacenza, a city administrative institution.

The two works also immerse visitors in the relationship between Genovesino and engraving, which is explored in the catalog by the contribution of the young scholar Francesco Ceretti. Indeed, the artist possessed a conspicuous collection of prints, which allowed him, Ceretti writes, “to appropriate engraving models, to re-propose or reinvent them with unscrupulous ease.” For many of his works, in fact, it is possible to find precise precedents in printed production: the scholar points out that even the Holy Family of the Gazzola Institute and the Lute Player derive from two engravings, respectively by Raffaello Schiamanossi (in turn derived from a drawing by Luca Cambiaso) and Hendrick Goltzius. The Palazzo Galli exhibition presents visitors with two Slaughters of the Innocents, one engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi from a drawing by Raphael, and the other by Marco Dente from a drawing by Baccio Bandinelli, which constitute the two precedents of Genovesino’s Slaughter identified by Ceretti, but not only: the delightful Sposalizio mistico di santa Caterina, a small panel preserved at the Episcopal Seminary in Cremona, owes its obvious Correggio vein to the fact that it turns out to be taken from a 1620 engraving by Giovan Battista Mercati, itself derived from Correggio’s Sposalizio mistico di santa Caterina, a work now in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte but formerly in the collections of the Farnese family. In the exhibition, panel and engraving are displayed side by side, but one must wonder whether Genovesino took Mercati’s print, or even Correggio’s masterpiece itself, as he could easily have seen it during his stay in Piacenza. Tanzi notes, however, in the catalog entry, that the evidence favors the engraving, for several reasons, "beginning with the insistent graphism with which the painter constructs the Cremonese painting compared to the luminous atmosphericity of the panel now in Capodimonte, where the chromatic choices are played out under the banner of a delicate palette, embellished by subtle nuances that do not find their counterpart in the execution for planes of color refined yes, but precisely defined."

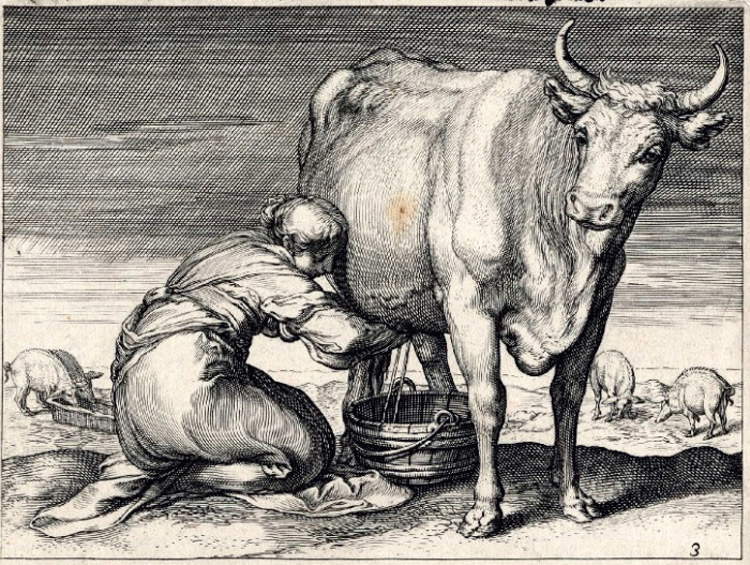

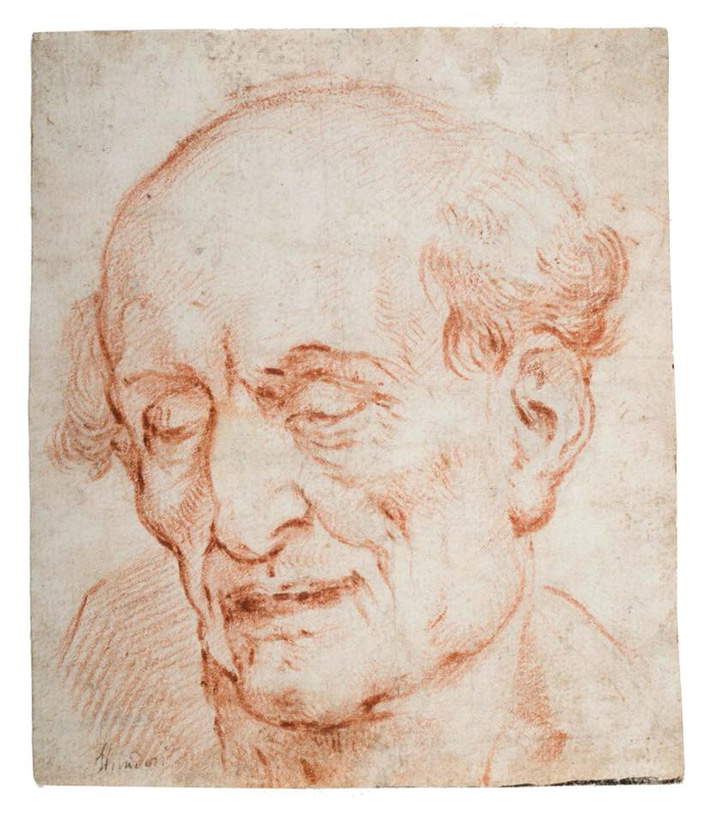

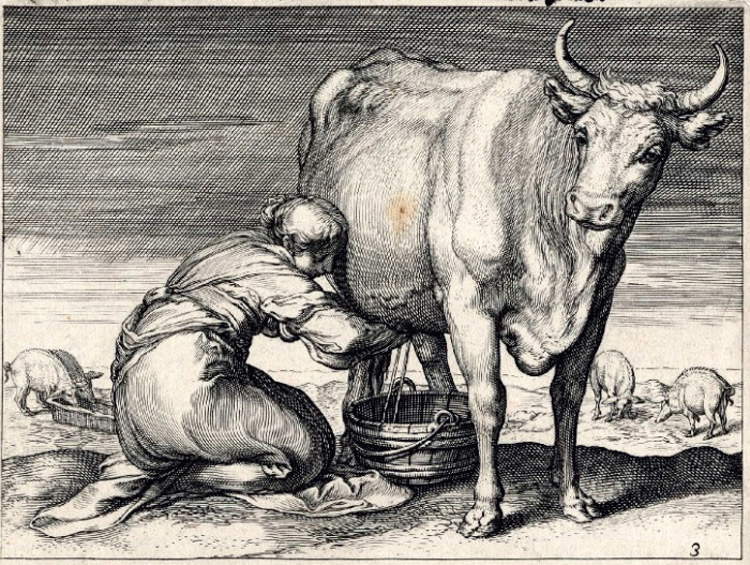

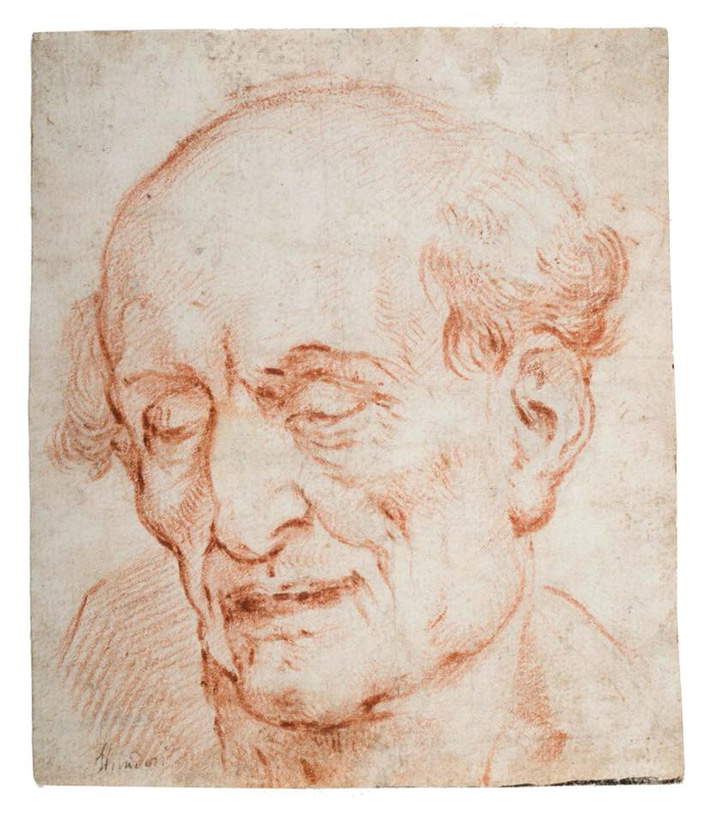

Two paintings from a private collection, conceived as a pendant and made known on the occasion of the Cremona monograph (in the catalog, in a card by Beatrice Tanzi, who pointed them out after a cue from Francesco Frangi), where, however, they had not been exhibited, arrive in the show: they are a Satyr milking a goat and a Villanella milking a cow, the latter probably derived from a Milking and Heifer by an anonymous engraver, itself inspired by a Prodigal Son of 1603-1605 by Jan Saenredam. Ceretti points out that "Miradori’s stylistic signature is recognizable [...] both in the effervescent dress of the villanelle, an exquisite reminiscence of the drapery of the Lute Player at Palazzo Rosso, and in the palette played on earthy hues, enlivened by white and reddish tones, according to the customs of the Ligurian’s coloristic vein,“ and adds that this ”animalistic attention" evident from the pair of tablets turns out to be a constant in Genovesino’s production of the fifth decade of the seventeenth century. That the painter was an excellent animalist is a well-known fact, while his talent as a naturamortista is more elusive: Laura Bonfanti recalls that research allows us to hypothesize that Genovesino executed several autonomous still lifes (after all, his familiarity with natural motifs is evident not only from the paintings with animals, but also from the frame with putti and flowers of 1652, preserved in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Codogno), suggesting that interesting lines of research could open up in this regard. Finally, another interesting front that could open up in the future is the one related to Genovesino’s graphic production: at the Palazzo Galli exhibition, in fact, a Studio per il volto di un vecchio (Study for the face of an old man) is on display, a drawing that represents in this sense “the only specimen definitely referable to Miradori’s production” (so Marco Tanzi in the catalog entry). It is an unpublished one that, as the curators state, emerged from a private collection while the Cremona exhibition was in progress: given its close stylistic relationship with the Miracle of the Mule in Soresina, and given also an eighteenth-century inscription assigning it to the Ligurian artist (a precise reference that “would not be justified [.... in years when the critical fortune of Genovesino was limited to a very small circle of amateurs”), there are no doubts about the authorship of the sheet, which therefore represents the first, fundamental piece to reconstruct the artist’s graphic activity.

--

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Punishment of Core, Dathan and Abiram? (canvas, 71.8 x 117.7 cm; Parma, National Gallery) |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Beheading of St. Paul (1642; canvas, 190.5 x 260 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

|

| Beheading ofSt. Paul, the wall with Genovesino’s painting and Martyrdom of St. James the Greater, engraving by Giovanni Battista Pasqualini (from Guercino) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Martyrdom of St. Lawrence (1643; canvas, 72 x 153 cm; Piacenza, Private Collection) |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Massacre of the Innocents (1643; canvas, 72 x 153 cm; Piacenza, Private Collection) |

|

| Marcantonio Raimondi (based on a drawing by Raphael), Massacre of the Innocents (1511-1512; burin engraving; Chiari, Pinacoteca Repossi) |

|

| Marco Dente (from Baccio Bandinelli), Massacre of the Innocents (1519-1520; burin engraving; Chiari, Pinacoteca Repossi) |

|

| Comparison of Genovesino’s Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine (panel, 29 x 23 cm; Cremona, Bishop’s Seminary) and Giovanni Battista Mercati’s Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine by Correggio (1620; etching; Reggio Emilia, Panizzi Library) |

|

| Luigi Miradori known as the Genovesino, Villanella milking a cow (panel, 41.5 x 52 cm; private collection) |

|

| Anonymous engraver, Milking Woman and Heifer (after 1611) |

|

| Jan Saenredam, Prodigal Son (1603-1605; burin engraving; Chiari, Pinacoteca Repossi) |

|

| Luigi Miradori called the Genovesino, Study for the Face of an Old Man (red pencil on slightly yellowed white paper, 15 x 13 cm; Private collection) |

A solidly scientific, serious and even courageous exhibition at a time when it is not an easy operation to do research and propose to the public names of authors who deviate from the usual roster (and so kudos to the Banca di Piacenza, which has excellently invested in a project that is not the easiest, but at the same time represents a small jewel in the panorama of national exhibition activities), Genovesino and Piacenza tries to shed light on a subject that is anything but easy, thus opening a new chapter in the history of the rediscovery of an artist who needs to be explored in depth, but who is gaining increasing interest from both the public and critics (evidence of this is, for example, the attention received by the Martyrdom of St. Alexander, another painting that recently emerged and is on display at the exhibition The Last Caravaggio at the Gallerie d’Italia in Piazza Scala in Milan). The result is a portrait of an artist who, despite the poor fortune he encountered during his stay in the city, which resulted in a period that almost forced him into destitution, nevertheless had the opportunity to establish relationships that would continue even after his move to Cremona, as attested by the canvases he executed for Piacenza even after 1635. A portrait, of course, open to future contributions and developments: apart from some pioneering studies of the twentieth century (such as those of Mina Gregori and Roberto Longhi, who is credited with having rediscovered the Genovesino), the studies around Luigi Miradori are, in practice, just beginning, and the Palazzo Galli exhibition is clear in underlining how various questions that emerge from the works gathered here will certainly have to be studied in depth and could reserve interesting surprises.

Of great interest, finally, is the catalog, published by Officina Libraria: Vittorio Sgarbi’s introduction traces a brief profile of the artist, then deepened with the essay by the three curators who take stock of the current state of research. This is followed by the aforementioned contributions by Laura Bonfanti and Francesco Ceretti, dedicated to the two main focuses of the exhibition, namely, as mentioned, the relationship between Luigi Miradori and Piacenza, and the connections between paintings and printed productions. Note of merit (which may seem trivial, but it is indeed a practice not so widespread) for the inclusion of an index of names, which greatly facilitates the consultation of the volume.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.