Severe and Miraculous. Following Caravaggio "with vigorous and dyed manner, " from July 28 to October 14 at MuMe, Regional Museum of Messina, is an exhibition with something of another era. The dry and rigorous set-up concedes nothing to the expectations (or pretensions) of a visitor now spoiled by a fruitive paradigm that envisions his involvement with the most subtle and advanced exhibition techniques and technologies. Between panels, essential didactic apparatus and shadow-shrouded rooms, the paintings surface to observation as naked truths, skillfully brought into focus by a luministic strategy that is as simple as it is effective.

The overall effect, of severity as we were saying, gives the impression of having plunged into the years preceding Longhi’s exhibition dedicated to Caravaggio in 1951 at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, where between counter walls and theatricalizing solutions Roberto Longhi “gave back” to the world what until then was a great artist for the few and at the same time created an inalienable icon. A gigantic reminder just to say that the non-risky proposition of a “tout court” exhibition can only be picked up in the 21st century if the discipline of scholarly research remains the beacon of curatorship. Choral, the latter is owed to the museum’s four art historians, Elena Ascenti, Giovanna Famà, Alessandra Migliorato and Donatella Spagnolo.

Arrangements

Arrangements Set-ups of

Set-ups of Preparations of

Preparations ofMiraculous, we said of the exhibition as well. Because in fact the museum’s director, Orazio Micali, was able to make a virtue out of necessity. The exhibition, which cost just 67.344.00 euros (no catalog), was entirely prepared with economy solutions that, rather than highlighting managerial skills of the director, so much appreciated seamlessly from the previous to the current ministerial course, have made Micali a true “deus ex machina,” always on site, ready to solve every step of a set-up that has also had to deal with the continuous blackouts related to the great heat and fires that just a few days before the inauguration had brought the city to its knees. With no water and no light, with a staff already stretched thin, the paintings under the watchful eye (and lent arms) of the architect director, found the right alignment on the walls where the only sources of light, in the agitated final moments, were flashlights and laser pointers. We could say that the final minimalist staging was inversely proportional to the pathos behind the scenes.

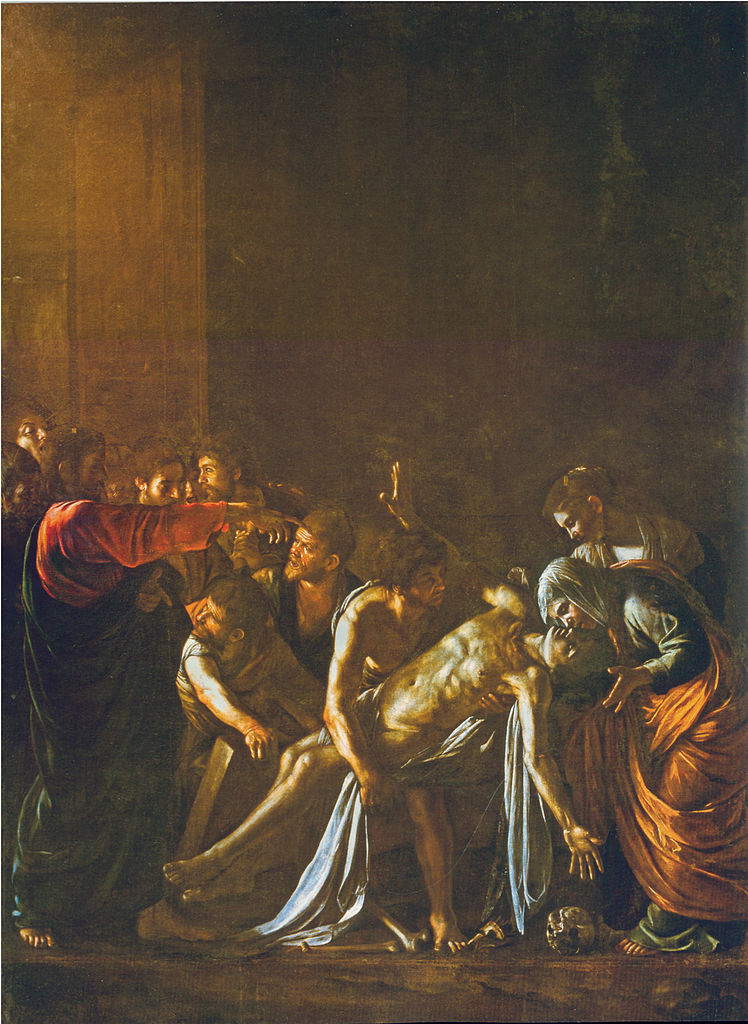

With an unparalleled advantage, compared to other exhibitions devoted to the Caravaggesque painters (even compared to the one, to stay in Sicily, at the Regional Gallery of Sicily at Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo in 2017), the exhibition’s itinerary, set up in the former Filanda Mellinghoff, the museum’s old site used with the opening of the new one for temporary exhibitions, complements the permanent collection. That of the Caravaggesque painters of closer observance, Rodriguez and Minniti, which winds around the room reserved for Caravaggio’s two masterpieces, the Resurrection of Lazarus and theAdoration of the Shepherds, and is articulated between the first and second exhibition levels, in a relationship of continuity. The first phase bears witness to Caravaggio’s innovative experience with diachronic perspectives and thematic hooks that testify to its premises and consequences, while the second relates to the parallel emergence of the Roman classicist currents being imported to the city. Exhibit rouge reproposed in the temporary exhibition.

And visitors have definitely shown their appreciation for the “Caravaggesque guests in the house of Caravaggio” formula: as of mid-September, the museum has already surpassed the takings of the entire 2022, which had been higher than those of 2019, the last pre-pandemic year; with the well-founded expectation of beating at the end of the exhibition even the takings of 2017 in which the new museum venue had been inaugurated.

Let’s face it, an exhibition on “Caravaggism” is more challenging than an exhibition on the star Caravaggio. It is one of the most arduous topics in art criticism. Longhi disdainfully rejected it, considering the term tied to a conceptual category and therefore not applicable to works of art. Well was chosen, therefore, already from the title of the exhibition to avoid it, inviting, instead, the visitor to dispose himself to the visit “following Caravaggio.” On the trail of his passage through Sicily, with 52 works, of which just over half are on loan from Palazzo Abatellis; Museo diocesano di Palermo; Curia arcivescovile di Palermo; Curia arcivescovile di Messina, Lipari and Santa Lucia del Mela; Lucifero Foundation in San Nicolò; Palazzo Alliata di Villafranca in Palermo; Castello Ursino Civic Museum in Catania, as well as from the Ministry of the Interior - Fondo Edifici di Culto and private collections. Of the twenty-five works from the Messina Regional Museum itself, 15 come from storage, in more than one case exhibited for the first time.

In the itinerary proposed to visitors are exemplified the painters who, between eastern and western Sicily, had breathed the oxygen of innovation, assimilating it into a personal and autonomous reworking of the language of the Lombard master, in which the use of color and chiaroscuro deflagrates the expressive force of the “inventions.” A revolutionary language effectively synthesized by Francesco Susinno, an eighteenth-century Messina historiographer, in the syntagm “vigorous and tinted manner,” taken up in the title of the exhibition.

The chronological range is between the mid-sixteenth century and the 1930s and 1940s, with outcomes of varying quality. Weak in the Christ at the Column of Catania, where the figures appear flattened on the surface, nullifying the attempt to give them prominence with chiaroscuro, or in the Conversion of St. Paul, by Antonino Barbalonga Alberti and helpers, with the saint’s expressionless face bizarrely offset by the gaze of the white horse that emerges out of the canvas straight toward the viewer. It rises, however, like a solo, in Filippo Paladini’s Saint Francis in Ecstasy, shortly after his encounter with Caravaggesque works; in Minniti’s Miracle of the Widow of Naim; in Saint Charles Borromeo intercedes for the end of the plague in Milan, with the perspective flight of rooms connoted by a bold foreshortening, almost a metaphysical vision that rips through the burnished wall on which the figure of the saint stands out; or again in Rodriguez’s Commiato dei Santi Pietro e Paolo prima del marttirio (Farewell of Saints Peter and Paul before the Martyrdom ), one of the highest Sicilian proofs of Caravaggio’s understanding in terms of dramatic charge and pictorial values. Among these works in the Messina museum’s holdings should also be mentioned the delightful oil on copper a Still Life with Fruit, Vegetables and Quince, dubiously traced back to Van Houbracken.

The exhibition criterion, however, does not have a monographic slant on individual personalities, favoring a criterion by epochs, themes and significant strands that encourages comparisons and cross-references. After almost seventyyears since the Milan exhibition (not to mention Caravaggio returned to the Palazzo Reale in 2006) and forty since the historic one of 1981-82 at the same museum on the banks of the Straits, in between studies, research, documentary updates, findings and let’s throw in the sensationalist eagerness aimed at enriching the master’s catalog in ways once unthinkable, the exhibition does a good service to studies, with its unsurprising juxtapositions of little-known works or those resurfacing from storage, intended also to stimulate new reflections on the geography of routes and exchanges between Sicily andEurope in the first half of the seventeenth century.

With one exception to the general criterion: the room entirely dedicated to the Messina outsider Giovan Simone Comandé, curated by Famà, to whom is due meticulous research aimed at highlighting a painter "always poised between late Mannerism and naturalism, trait d ’ union between Filippo Paladini, Antonio Catalano l’Antico and Alonzo Rodriguez, never really ’adhering’ to Caravaggio, but certainly one of the forerunners of the naturalistic reform in Messina."

After the introductory room, we begin with the historical context in which the Caravaggesque leaven would come to be grafted, that of Messina in the golden years between the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century. In painting the climate of assimilation of Tridentine precepts is documented by the Neapolitan Deodato Guinaccia, in Messina from 1570 to 1585. Still steeped in mannerism, his Pietà is inspired by a famous drawing by Michelangelo Buonarroti executed for Vittoria Colonna and translated into painting by Marcello Venusti, among the leading exponents of Tuscan-Roman artistic orthodoxy. Other examples of counter-reformed altarpieces are the Madonna and Child in Glory between Saints Placido, Flavia, Eutychius and Vittorino by Antonio Catalano l’Antico, a pupil of Guinaccia, and theAdoration of the Magi by Giovan Simone Comandè. A previously unpublished work(Madonna in Glory between St. Erasmus and St. Anthony of Padua) by Gaspare Camarda signed and dated 1608, the year of Caravaggio’s arrival in Messina, photographs the cultural and artistic terrain that would be shaken by the Master’s revolution.

In the third room, the comparison is with one of Caravaggio’s most popular themes, the Passion of Christ: From Minniti’s Christ Carrying the Cross toEcce Homo, once assigned to the Rodriguez and in the exhibition indicated with a more cautious “unknown,” an ancient copy of the Genoa exemplar, on whose dubious as well as incredible attribution to Caravaggio the Madrid painting discovered in the Pérez de Castro Méndez; up to a Coronation of Thorns, where the theme of Christ Mocked also appears, useful, on the contrary, to document the absence of the direct influence of Caravaggio in a work of the late manner between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

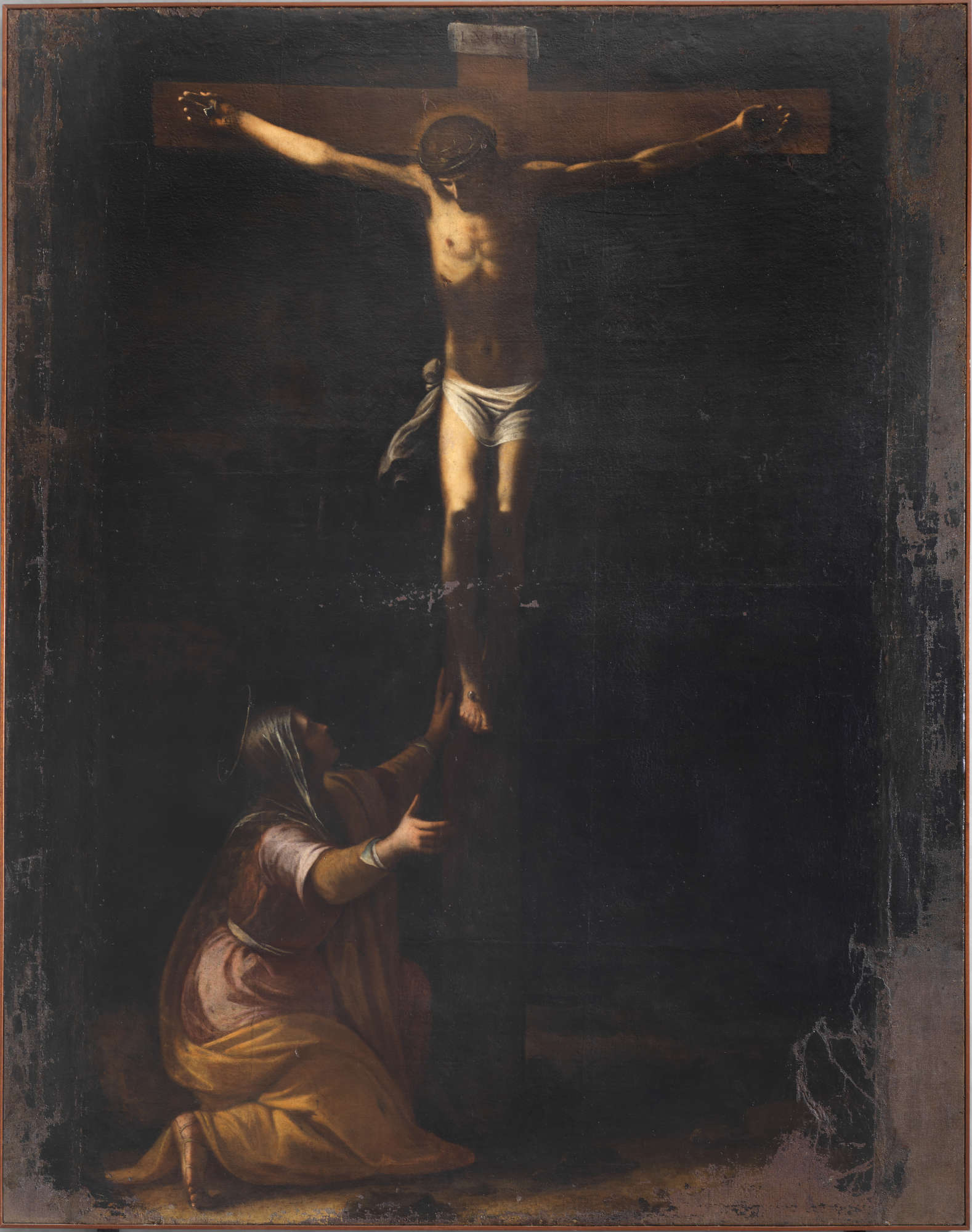

To the crucial years of Caravaggio’s influence on Sicilian painting, from about 1610 to 1629, is devoted the next section, which runs through four rooms. In the first (“Caravaggio’s Naturalism in Sacred, Allegorical and Everyday Themes”) it is possible to follow the gradual assimilation of Caravaggesque ideas by artists such as Minniti, in Poverty in the Ingenious Rich and Christ Crucified and Mary Magdalene; and Rodriguez, with the Farewell of Saints Peter and Paul. In the second room, Caravaggesque reflections combine with the Flemish landscape. In Minniti’s two Scenes from the Parable of the Good Samaritan, the natural backgrounds are almost hapaxes in the early seventeenth-century Caravaggesque Sicilian context, because of the unusual outdoor settings with passages of landscape populated by wayfarers, hunters or shepherds engaged in daily activities unrelated to the main subject. It owes part of its attractiveness precisely to the landscape backdrop of Naim ’s Miracle of the Widow, transferred here from the Museum’s permanent exhibition and considered the masterpiece of the painter who was a friend of Caravaggio. The protagonist of the third room of the section are the allegorical paintings The Touch and the Taste, part of the series of The Five Senses of Caccamo, attributed to Jan Van Houbracken, in which a narrative and theatrical attitude, together with sensitivity to the popular world, offers the visitor another fundamental aspect of Caravaggio’s message. From eastern Sicily we move, then, to Palermo, between 1621 and 1622, in the room that closes the section, with theLast Supper painted for the convent of Santa Maria di Gesù by the Racalmutese Pietro D’Asaro, an eclectic artistic personality, and with theElemosina di San Carlo by Pietro Alvino.

A prominent place in the itinerary, we said, has the salon dedicated entirely to Giovan Simone Comandè, “perennial river of painting,” whose personal adherence to the Caravaggio lexicon is revealed in the “imposing figure of Saint Anthony Abbot (of the Regional Museum, ed.) and in the chromatics modulated between the severe tones of brown and black,” observes Giovanna Famà, a scholar to whom we owe the recomposition of the catalog of paintings (from the end of the 16th century to the first thirty years of the following century) attributed to this painter celebrated by the most ancient historiography ancients, and in whose works, Famà writes again, “one finds, within a composite culture of a high level, complicated feelings where the Caravaggesque experience, direct or inferred from school works, shines through without ever being the protagonist.” Proof of this is also the precious Vocation of St. Andrew or Miraculous Fishing.

From the salon one passes through a dark tunnel, almost an anti-structure of decompression from the previous monographic space to arrive in the room where the new suggestions are documented, between the fourth and fifth decades of the seventeenth century, between naturalism, refined classicism and baroque, with works still by Minniti and Rodriguez, along with Jusepe De Ribera and the Dutch Stomer (or Stom). From here we move on to the main exponents of the pictorial renewal present in Messina from the fourth decade of the seventeenth century, who, although in a changed cultural climate, were still influenced by Caravaggism: Giovan Battista Quagliata, with Saints Cosmas and Damian; Antonino Barbalonga Alberti, with the large ribbed canvas depicting the Conversion of St. Paul, returned to the public after the recently completed restoration; and Nunzio Rossi, with an unpublished painting with the same subject.

Concluding the visit is the section “Tangencies with Flanders, Naples, Genoa and Malta in Some Case Studies,” in which the cards on the table are shuffled, academic certainties become perilous and hypotheses are likely to caraculate. While the simple visitor is allowed not to bridle the spirit among paintings, unpublished or little known, or on the contrary, very well known but with controversial attribution, put in dialogue with each other in the name of a common Caravaggesque figure. Here, then, is also the unique opportunity to closely examine Santi Pietro e Paolo from Santa Lucia del Mela, for many years “in search of an author” among the Sicilian Caravaggesque painters, or to linger in front of the homage to Caravaggio in the unpublished Martirio di Sant’Orsola, taken with some variations from the Caravaggesque original of 1610 (Naples, Gallerie d’Italia).

The exhibition, in conclusion, far from simplistic reconstructions, is a valid attempt to recount the real “fortune” of Caravaggio’s painting in Sicily, at his time and thereafter, in overall historical terms and not only historical-artistic or merely stylistic.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.