As Andrea Emiliani wrote in 1975, signing the catalog of the exhibition that is still considered a landmark in the critical relocation of Federico Barocci, an artist who never achieved the status of the revolutionary who conditions an era and redefines it according to his own parameters: Barocci will long remain in that intermediate space of one who stands on the two stirrups of the prosecutor and the anticipator. With his great painterly qualities and remarkable training culture he is the heir who lengthens the trajectory of Raphaelism “in an existential rather than humanistic direction”; but, on the other hand, he is also the hypersensitive innovator who breathes in the airs of the nascent classicist naturalism of Emilia without ever fully landing there because of his visionary understanding of color: not a relationship with the natural, but the verisimilitude of the “impossible believable” (pre-Baroque, after all; he could not have aspired to more). While offering new stimuli, even in terms of classicism Barocci would be overwhelmed by the peremptory expressive force of Annibale Carracci. At the same time, in an anti-Mannerist direction, he will manifest formal languor that already tilts toward the Baroque, particularly with a poetics of the affections based on the truthful potentialities of sentiment, which in him never “reaches physiological maturity,” but touches the heights of what we might call precisely a magical luminism.

With formidable definition, Emiliani compares Barocci’s light-color form to “photographic emulsion” (taking cues from Mengs) since his compositions are apparitions evaporated in the light and gentle clarity of forms. Unusual moments of transparency were readily found by a seventeenth-century artist, a native of Pesaro and for this reason nicknamed the Pesarese, Simone Cantarini, in the sublime canvas of the Beata Michelina- “that veiled color that blurs the image, that restless lumeggiare,” accurately rendered by Arcangeli; and it should not be forgotten that Cantarini was a heretical pupil of Guido Reni, who was very attentive to Barocci’s painting.

Despite this interweaving of relationships, the Urbinate, even in the criticism of the moderns closest to our time, never managed to “break through the wall of mass notoriety.” On the contrary, Emiliani continues, “Federico Barocci’s time is certainly that of the dissolution of the Renaissance system to a restless condition of uncertainty...”; that is to say, he bridges the severe Renaissance form that then juts out toward transcendent transparency by making “miraculous visions natural,” yet without marking his own time with a strong style and revolutionary language. He was, in short, a genius of the highest pictorial caliber, but not the performing artist of an era.

About Barocci there is still the vulgate that sees him as a man marked by illness. And certainly he was of a frail constitution. The mythographic pendant is in the narrative of when-while in Rome he was gaining consensus and space among high-ranking patrons-he paid dearly for the fatal envy of his colleagues who, biographers tell us, Bellori in primis, poisoned his salad and thus marked forever his already precarious health condition induced by a particularly hostile helicobacter, which had caused him a’persistent ulcer hindering and limiting his working time-from the letters of his most loyal supporter, the duke of Urbino Francesco Maria II della Rovere, one can sense his impatience with the tardy painter, whose slowness by this caused him diplomatic annoyances with the great patrons whose liaison with Barocci he had made: in a letter of 1588 the prince even went so far as to ask himself in utter exasperation whether it would not be better for the artist to die of his illness than to continue to give him all that trouble. It was still an era where a painter could weigh in on the fortunes of politics.

The Uffizi preserves Della Rovere’s splendid portrait that Barocci made of him wearing armor while resting his right hand on his gleaming helmet, a canvas now on display in the retrospective the city of his birth now dedicates to him, right in the Ducal Palace (until October 6), alongside other portraits, a genre in which Barocci was an undisputed master. Thus Urbino settles its debt by mounting for the first time a retrospective on its illustrious painter.

Francis Mary II participated in 1571 in the Battle of Lepanto, leading an army of two thousand soldiers and emerging triumphant. This is what Barocci’s portrait is meant to celebrate: the image of a virile man, not overly emphatic, willing to exhibit the calm certainty of his own means in the confident gaze of a condottiero. This pride of the future ruler (his father Guidobaldo died in 1574) confirms the supreme prestige and respect reserved for the painter in the court so much so that, as recalled in the exhibition catalog - published by Electa - Raffaella Morselli, it was the duke who visited Barocci in his home, reversing the courtier relationship, as a sign of the uniqueness of their relationship (the painter, born in 1533, was sixteen years older than the duke). But Barocci,“ the scholar points out, ”was far more than a court painter; he can be defined rather as the superintendent of the artistic affairs of the duchy (in a small way, as due proportion dictates, Barocci was to the duchy what Raphael was to papal Rome).

Trained in music, architecture, and the other arts-through his youthful experience with Bartolomeo Genga, an architect, and his father Gerolamo, a painter, sculptor, and architect from whom he may also have taken rudiments in sculpture-returning to Urbino from Rome in 1565, he then became the new prince’s adviser on all decisions concerning the arts. Meanwhile, his notoriety in Europe was expanding thanks in part to the spread of his visual inventions, which engraving stimulated, so that Barocci bypassed Italian borders while remaining stationary in the duchy of Marche.

But on the little story that tends to motivate Barocci’s sudden departure from Rome after the poisoning episode, Emiliani was skeptical. Too anecdotal and not very credible, according to the scholar. After all, Barocci in Rome was seen as the continuer of Raphael’s line, esteemed for his painting skills by Taddeo Zuccari and the elder Michelangelo; moreover, during his Roman sojourn, the Urbino established relations with Saint Philip Neri, who declared all his esteem for the painter by commissioning from him for Santa Maria in Vallicella the great altarpiece of the Visitation, a work, the chronicles narrate, in the presence of which the founder of the Oratorians reached ecstasy. In the 1975 essay, Emiliani never gives the impression that he considers Barocci a coward, one who surrendered to human wickedness; it would have been like reducing his luminous painting and gentle form under that view: a sweetened idea, today we would say buonista, when the very last period of his artistic life transposes on canvases a Christian piety marked by supremely tragic stigmata; a “mystical” phase that it would not be improper, in terms of poetic intensity, to place next to the noche obscura of St. John of the Cross.

Moreover, Barocci’s elegance is not a psychic reduction of mannerist timbre, indeed; nor is it a balancing act between naturalism and classicism. Rather, its “heavenly” transparency is an existential mask. Emiliani spoke of the return to Urbino as a desire to recover one’s cultural roots. Barocci was to be in this sense the exemplary standard-bearer of the duchy, while Urbino’s fortunes on the political scene were, however, declining; and at the same time he bore witness to the aesthetic and religious re-foundation desired by the Counter-Reformation. The Visitation does indeed embody a humanity faithful to Christian truth, but in its depiction also close to the condition of the simple (along the lines of the low church, recalled by Emiliani, which has its champions in the Oratorian and St. Charles Borromeo): note the singular handshake between Elizabeth and Mary embracing each other; it could be the street meeting between two ordinary women divided only by the gap in age, but united by the feeling of a new embodied faith. Sprouting from the left of the painting is the donkey’s head, which seems to be inspired by secret thoughts (donkeys also have a mind, “divine” would say the devotees of alchemy and Kabbalah): it is, like Caravaggio’s donkey in the Flight into Egypt, whose far from ebete eye gazes, as it were “in the car,” at the sacred stone summoner who testifies to the vigilant attention of the divine guarantor on the Holy Family.

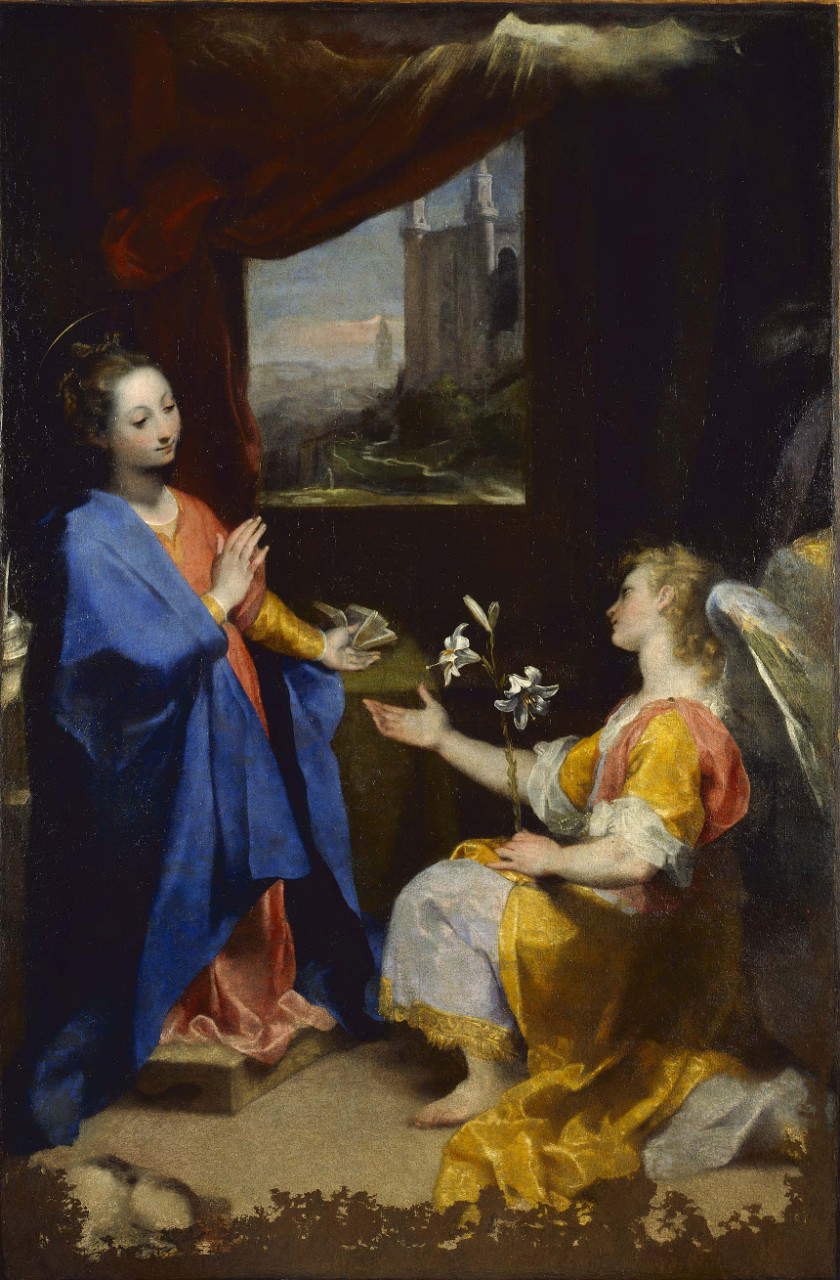

The Urbino exhibition constitutes a fundamental fine-tuning, even in comparison with Emiliani’s, for the emphasis it places on Correggio, of whom Barocci exhibits more than one quotation confirming an Emilian stage of his own and a de visu experience; but also, for how he insists on the last creative period, where the painter’s state of mind is expressed in the “wonder of the night,” as Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari (curator with Luigi Gallo, of the review) writes. Atmosphere that, if, on the one hand, makes one think of a meditation on Tintoretto, with a transfer to Venice, is nevertheless rooted in the nocturnal sense that we already find in Raphael(Liberation of St. Peter); and in the penumbra of condensed lights, a splendid synthesis of various thoughts amalgamated, for example, in the pictorial fabric of theAnnunciation in the Vatican Museums, also seems to bring out Leonardo reminiscences. On the other hand, in the chiaroscuro drama enveloping the Escape of Aeneas from Troy Barocci summarizes a long range of experience, from Raphael to Tintoretto, passing through the luministic atmospheres of Jacopo Bassano.

TheInstitution of the Eucharist seems to be the work of a painter provoked by a strong feeling for the real, with effects of reality deeply “human but not humanistic,” as Longhi wrote of Caravaggio; lines of study that will have to be rethought in the light of this exhibition, the revival of which has the force of a new beginning, that is, retracing the paths taken by Barocci and following in the footsteps that make him an anticipator of Baroque culture.

The counterpoint established by Argan between Barocci and Caravaggio, does not indeed make them distant in the feeling of reality, even if the method separates them: that of the Urbinate produces dozens of study drawings, on account of which Bellori already spoke of “studio vigilanti,” which is then followed by the involvement of collaborators in the development of his inventions through the reuse of models and structures; while in Caravaggio the urgency of reality, of the real, moves from the praxis charged with furor, which sees him as the sole protagonist: the Lombard painter, it is well known, did not delegate to anyone the completion of the work, supremely jealous as he was of his own inventions. And this formal and aesthetic difference between true and verisimilitude, properly methodological and poetic, aroused in Bellori a Caravaggesque “antipathy.” The issue was addressed again in 2000 in Rome, in the exhibition dedicated to the seventeenth-century writer and entitledThe Idea of Beauty.

Indeed, Barocci is also a characteristically tormented man; his ulcer seems, as, moreover, current medical research also reminds us, to be the psychosomatic effect of an exacerbated soul, about which Ambrosini Massari writes in the catalog. The scholar, specifically, argues that the more physical and inner suffering acted on Barocci “the more his works expressed that continuous smile that makes the painter a crystalline protagonist of the Counter-Reformation, or rather the Catholic Reformation.” Remarkable theme. As modern psychologists tell us, a repeated smile, almost reactive to the inauspicious events of life, often conceals a melancholic. For Barocci, the ulcer was the viaticum to a profound knowledge of the spirit of the world, which caused him lacerating torment because it was clearly far from the evangelical good. A great Italo-German theologian who was a friend of many artists, I speak of Romano Guardini, wrote penetrating pages about artist melancholy that should be reread. For the theologian, the German root of the term melancholy, Schwer-Mut, does not mean “black humor,” as we are wont to say, but “grave humor” (pregnant, heavy): it is something that looms over the soul and produces malaise and self-consciousness. In general, the melancholic experiences a feeling of the inescapable that “exposes him to all risks.” The artist’s tension at the fulfillment of the work burdens him with a restlessness and dissatisfaction that can become dangerous, as “the greater the value, the more destructive effects it can have.” In essence, melancholy is life playing against itself, and “the instinct of self-preservation, self-esteem, the desire to do one’s own good can be distorted, made uncertain, uprooted by the instinct of self-destruction.” Longing for the beloved also makes itself felt as a “contradiction between time and infinity,” a longing for the absolute, of which melancholy embodies “the pain caused by the birthing of the eternal in man.” Melancholy will also be “relation to the dark foundations of being,” Guardini writes, but this darkness is not to be confused with the negativity of darkness, but rather understood “as a strange form of approaching light.... Darkness is bad, being something negative. Darkness, on the other hand, belongs to the light.” If in the latter part of Barocci’s life there recurs frequently, as Ambrosini Massari writes, “the setting by nightlight,” one may ask then whether the luminous transparency of the first period and the dark nocturnal projection of the last are not two sides of a single melancholy of the artist. The answer to this question may point a different way to definitively rescue Barocci from the misconception of a “smile” painting.

The author of this article: Maurizio Cecchetti

Maurizio Cecchetti è nato a Cesena il 13 ottobre 1960. Critico d'arte, scrittore ed editore. Per molti anni è stato critico d'arte del quotidiano "Avvenire". Ora collabora con "Tuttolibri" della "Stampa". Tra i suoi libri si ricordano: Edgar Degas. La vita e l'opera (1998), Le valigie di Ingres (2003), I cerchi delle betulle (2007). Tra i suoi libri recenti: Pedinamenti. Esercizi di critica d'arte (2018), Fuori servizio. Note per la manutenzione di Marcel Duchamp (2019) e Gli anni di Fancello. Una meteora nell'arte italiana tra le due guerre (2023).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.