The biggest mistake one can make in making an exhibition of artworks that should have irony as its common thread is to explain where it lurks by overwhelming it with words and reflections. But, on the other hand, what to do? Irony is a “celibate machine,” it admits of no explanation because to strip irony of the veil that makes it ambiguous and even contradictory is to bend it to rationality, which disassembles the “machine” into so many pieces, but thus scatters into the air the genius that made it what it was: a paradox. In irony, all the more so when lowered into the forms of art, the verbal element is almost always surplus to the functional “uselessness” of this bizarre way of saying where one thinks the opposite of what one is stating (perhaps). Removing the veil from irony is a bad joke. As Francesco Poli also reminds us in one of his recent books, Irony is a Serious Thing (Johan & Levi): irony should never be stated, i.e., reported or explained, because its way of being is to raise a doubt about what it proposes. We have all realized this at least once when in public we have heard someone make a statement and immediately afterwards say that it was “ironic,” for fear of being misunderstood: but misunderstanding is part of irony, and misuse of the rhetoric of negation that belongs to it also devalues the intelligence of others.

Texts explaining the reasons for an exhibition on irony should be limited to pure didacticism, where we simply tell the viewer that he is moving inside a room where not everything he will see is what it seems. Period. Then if one is grappling with a book, the only way, in my opinion, remainsecfrasis, the verbal analogy that speaks of the sublime concept in a work without ever naming it. To make reasonings, speculations beyond pure didacticism, betrays the sense of irony itself, which must be considered, Duchampianly, a nonsense irreducible to the logic of the rebus. Like the ready-made of the great prankster, the supreme illusionist or le Grand fictif, as Jean Clair called it half a century ago.

So how many questions does the exhibition Facile ironia, which MAMbo in Bologna opened a few days ago, pose? Are they more questions or does the intention to explain what eludes rational logic prevail? How is this ironic intention revealed? Long ago one of the great modern philosophers, Vladimir Jankélévitch, wrote that irony is asking questions to flush out the opponent who wants to prevail through a kind of hypocritical reasoning: “irony - in fact - is the bad conscience of hypocrisy.”

Beginning his investigation of irony in contemporary art, Poli wonders why it has often been the focus of philosophical, aesthetic, literary and linguistic studies, “but critical contributions of any significance that focus on the incidence of this fascinating and elusive mode of expression in the visual arts are inexplicably rare.” Jankélévitch, in what is probably the most important study on irony in recent centuries, published in 1936 and later expanded in 1950 under the title L’ironie ou la Bonne conscience, an essay that was also a programmatic palimpsest for his entire philosophical research, goes so far as to say that speculation and art are not ironic because “they lack the oscillation between extremes and the movement of dialectical coming and going from contrary to contrary.”

The discourse is somewhat elliptical, as is the irony after all; to understand it we must first enter, albeit briefly, into the history of this great French thinker. Born into a family of Russian Jews who immigrated to France, he was always faithful to his roots while not being an observant Jew (in the mid-1960s he blamed Heidegger’s support for the German and Nazi attack on Russia, raising fierce controversy). A lecturer at various universities and at the Sorbonne, where he sat on the chair of Moral Philosophy (in 1968 he was among the professors who supported the French May), he also proved to be a remarkable musicologist and pianist (he wrote memorable essays on Debussy and the ineffable and on Liszt). A disciple of Henri Bergson, to whom he devoted a successful monograph in 1931, he was an insightful interpreter of the concept of Je-ne-sais-quoi et le Presque-rien (the not-so-what and the almost-nothing), the instant that tests being, the ineffable, that which cannot be said. Jankélévitch calls it charme: the “principle” of “entities,” without itself being an entity, that is, something that can be located in space and time, for it is rather the witness to the total gratuitousness of the real. Irony becomes its revealing device because in itself it has no purpose, and when one wants to reduce it to criticism one realizes that in essence it denies itself a task that does not belong to it. Irony, as Poli rightly observes, “operates at the level of linguistic structures by affecting the plane of signifiers even before that of meanings.” On the “how” before the “what.” If irony, “true irony... does not have to be declared,” MAMbo then took on an arduous task and by paradox wanted to declare right from the title what irony is not and cannot be: “easy.” A title that works as an oxymoron?

But let us return to Jankélévitch. He is not entrenched in the false schema of irony as the aristocratic sister of the comedian or the joker; instead, he studies the irreducible negation of irony itself to something that makes people laugh: Severe ludit, because “irony plays seriously.” Jankélévitch’s thoughts on the qualities of irony, on the other hand, are quite clear: “it is laconic, it is discontinuous, irony is a brachylogy. Its style is elliptical.” And to quote another great Frenchman, Remy de Gourmont irony is a solvent of stereotypes, it is dissociative because it makes idées reçues react with something that there and then seems “strange” to us; that is not brutal but subtle, light, antitragic. Irony is the fundamental weapon of those who, like Socrates, know that they do not know; “the weapon of the strong,” Jankélévitch writes again, “is the patience of a god disguised as a beggar. This metaphor of dissimulation is an idea that could descend from the one who came to be seen as a Prussian Socrates, Johann Georg Hamann, also known as the ”Wizard of the North," a great thinker and critic of the Enlightenment, a friend in concordia discors of Kant. Hamann addresses the dereliction of God on Golgotha according to an idea of foolishness that contains within itself the Socratic irony: “his ignorance and folly.” What supreme irony to die as a man while also being God? But to understand this mysterious “negligence” one must be able to see beneath “all the rags and divine garbage,” Hamann argued. And perhaps the sharpest interpreter of this paradoxicality was Nietzsche when he invites us to think as if we were in a condition of strange blindness: “the right eye must not trust the left, and light will be called darkness for some time.” The purpose of irony, in short, is irony itself; it cannot be enslaved as a means to fight ideological battles; it is a viaticum to unmasking, a kind of rhetoric or language game, and a test of the suspicion that generates our disenchantment with the ambiguity of reality.

Similarly, dropping into the problem of art, Poli argues that “an ironic operation has an authentic artistic function when it is not an end in itself but succeeds in undermining homologated formal and iconographic schemes.” The vocation to discombobulate the cards links irony with a myth that comes from afar, that of the divine rascal (see Paul Radin) who in folkloric mythology is called a trickster, literally “trickster,” a “swindler,” whose amorality is proportional to the mission of collapsing cultural stereotypes to generate a new order of knowledge. A “swindle” that turns against the perpetrator if one does not resist the temptation to confess it. For example, Odysseus: he is the image of cunning, and the function of the ironic device is laid bare in the episode where Odysseus in front of the Cyclops-Polyphemus says his name is Nobody; thanks to this deception he manages to escape with his men. Having taken to sea with the ship, Odysseus nevertheless makes the mistake of wanting to reveal the irony that saved him and, swaggering, shouts to the Cyclops that if he is interested in finding out who mocked him, well, let him know that it was him, and his name is Odysseus, the son of Laertes of Ithaca. As we know, this recklessness gets him into a lot of trouble. Unveiling irony, then, can get downright serious.

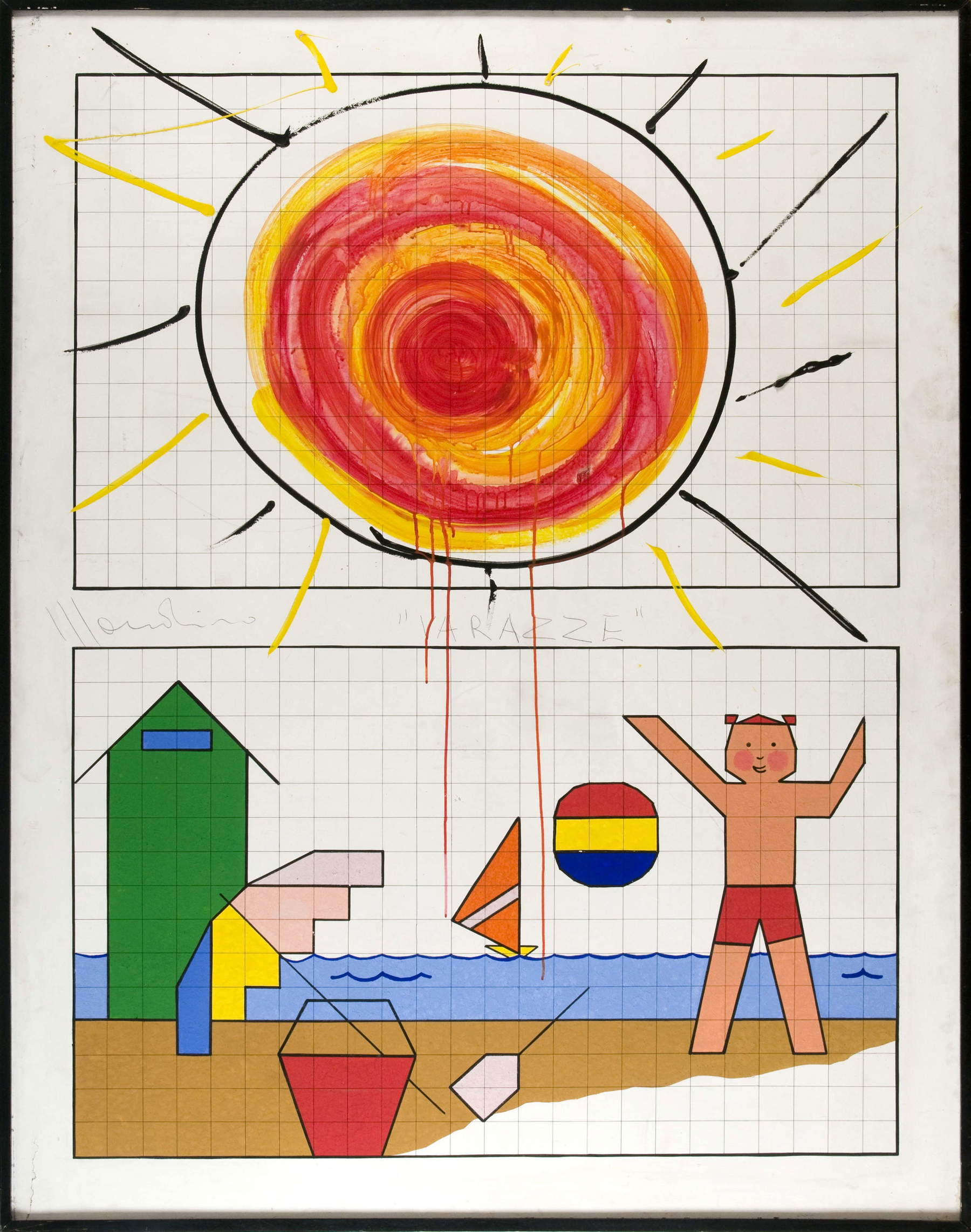

Francesco Poli’s book traces an overview of the main registers of irony: humorous, satirical, dramatic, tragic, transcendental, lyrical, melancholic, nihilistic, paradoxical. The fact is that irony is all of these things and none of them. In the MAMbo exhibition, however, “ineffability” seems to become even superfluous in works that discover themselves in a difficult condition precisely because they are part of a container that addresses the viewer by telling him: everything you see is ironic (starting with the bright colors of the walls, designed by Filippo Bisagni, as a revelation of the “rossian ghost”: the building, in fact, is the unfinished result of the renovation of the Sala delle Ciminiere designed by Aldo Rossi).

De Dominicis’s Mozzarella in a Carriage, a work from 1968-1970, deconstructs a reality-metaphor and reduces it to antiphrastic evidence with that lustrous white mozzarella that seems to have just emerged from its amniotic bath to “sit” prettily on the carriage seat. But is this really ironic, or does it stop at the level of intellectual sarcasm? Does it perhaps have something to do with the canulars that were repeated every night in the cabaret of Montmartre due to the brilliance of improvised blagueursactive in groups with such waffling names as “Idropaths,” “Incoherents,” and “Hirsute” that animated late 19th-century Paris. But irony is enhanced in the linguistic mechanism that challenges the commonplaces circulating in society, and perhaps even attracts criticism from viewers. As in Meret Oppenheim’s Le Déjeuner en fourrure, which, on the occasion of the Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition held at Moma in 1936-1937, then-director Alfred Barr called Service à thé en fourrure, confessing that it “embodies the most extreme and bizarre improbability.” so irritating is that irony to the respectable public of the time that - Barr admits - “tens of thousands of Americans expressed anger, laughter, disgust or joy.” But this confirms that irony in artwork is something “irreducible” that elicits opposing reactions among viewers by making its own paradox an allergy-producing substance.

Is Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit ironic? The description of the product, stated externally on the label glued to the tin, is certainly ironic: “Net content gr. 30. Preserved unopened. Produced and canned in May 1961.” But the irony remains intact as long as one believes the artist that with the éclatant gesture of the canned shit he really only intends to make explicit the great hypocrisy of consumer society (i.e., the redistribution of wealth through wider access to goods). The only way to thwart the Manzonian irony is to take a can opener and see what the can contains. But by then the mass bourgeois will have disproved himself by zeroing in on the economic surplus of the work of art ( kitsch here coexists with the capitalist realism of “seeing is believing”).

Perhaps the most interesting game that Lorenzo Balbi and Caterina Molteni, the curators of the MAMbo exhibition, propose to us (through Sept. 7, Allemandi catalog) is to test the declared “ease” by overthrowing its meaning: but theautoreverse of meaning gets jammed in works that want to be ironic by provoking laughter and sarcasm against someone. As happens, for example, in the trivial game provoked by Monica Bonvicini’s work: the bronze sculpture of a forearm and a hand in the act of grasping-weighing something comes out of the wall at crotch height and intends, as the title Prendili per le palle (moreover, already explicit in the work so as to be pleonastic) suggests, to criticize the triviality of Donald Trump and all that he represents: easy irony, indeed. Less funny, nonetheless, than a famous and grotesque little story spread perhaps to counter another hoax, the one about Pope Joan. According to this legend, every pope elected had to take a “manhood test” to attest to his masculinity and prevent a woman from ending up in the Petrine chair. The hand of a person in charge of the surreal task - like Bonvicini’s - had to attest that the newly elected “habet testicolos duos, et bene pendentes!” An absurd (and completely false) legend, but who can say that it did not also inspire Bonvincini for her anti-Trumpian irony?

The exhibition develops in several sections the different modes of artistic irony: irony as paradox, as play, as feminist critique, as an instrument of political mobilization, as institutional critique, as nonsense. Here are some examples. Of a more classical measure and internal to questions of artistic form are some works born at already historicized moments of the last century: Pino Pascali’s The Great Reptile, Vincenzo Agnetti’sSelf-Portrait with the inscription “When I saw myself I was not there” replacing the image of the face, Giorgio De Chirico’s melancholy Mannequin Painter, Salvo’s tombstone with the inscription “Salvo is dead”; while more contemporary installations such as Maurizio Cattelan’s pigeons or Paola Pivi’s polar bear seem directed toward a “playful” critique of emblematic situations of today (thenow irreducible aversion to the pigeons that spread guano everywhere in our cities, but are hired by the equally impecunious tourists for photos in Piazza Duomo in Milan or Venice; or, the solidarity with protection campaigns of the kind “nobody touch the bear,” polar or woodland, prompted by news events, where the bear thanks to art has been given a yellowish, bird-like plumage).

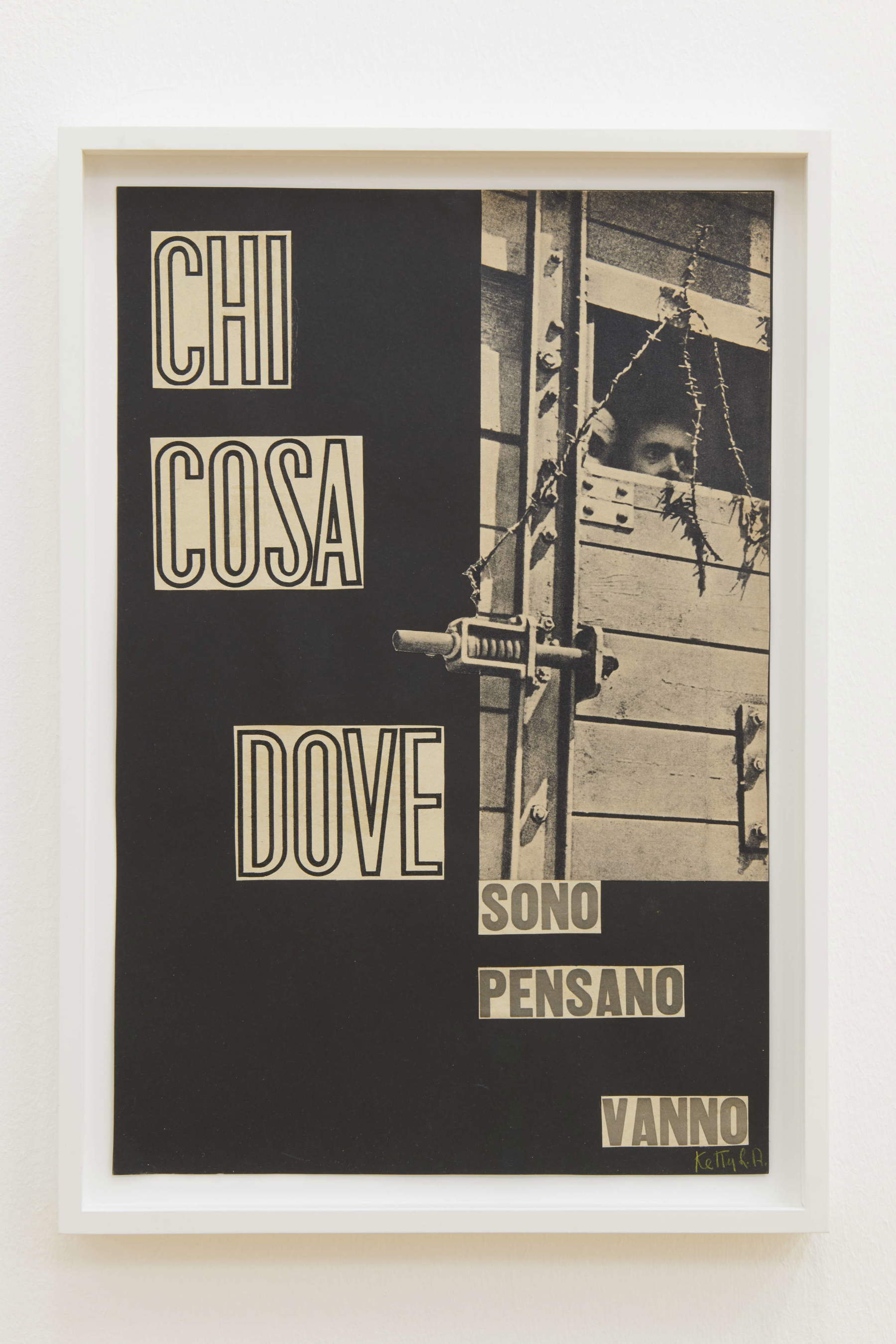

Still from the last century, we find Savinio, who makes a mountain of his phantasmagorical baubles fly on the carpet; and Donghi with The Dog Trainer: both belong to the poetic side of irony, like Bruno Munari’s “canvas with oil stains,” a true aesthetic calembour, as well as Aldo Mondino’s “Quadrettature”; while Lisa Ponti’s subtle paradox of colored signs-one of the most ironic works in the exhibition-becomes an amused critique of inherited artistic languages. On the contrary, the sections conceived with a function of social and political criticism lose, in my opinion, that ironic specificity that in art should remain internal to formalistic thinking and the critique of expressive languages (a balance that still resists, for example, in the collages on newspaper pages that Nanni Balestrini dedicates to Italian society in the 1960s), but often becomes a means of political struggle, losing that ineffability that is the ironic specificity.

The secret of all this is contained in Duchamp’s law: “n’importe quoi.” The “nothing,” which nevertheless conceals something. In this paradox that does not depend on an explicit meaning, but opens a gateway to the creativity of the common man, “we are all artists,” irony acts as a purgative administered to an academic idea of art; as much as it can become a mystification in so much of today’s miserable conceptual art, in Duchamp it instead stands the test as it stages different canulars. This is what the ready-made, the already made, tells us about, which for Duchamp is an objective correlative of irony. And it is ironic because it negates what Duchamp states, “n’importe quoi.” Everything matters to Duchamp, it does, and this is what I have tried to demonstrate in the book Out of Service. Notes for the Maintenance of Marcel Duchamp, written on the fiftieth anniversary of his death. Each of the Grand Fictif’s works arises from a biographical-existential background, and irony becomes the trojan horse he introduces inside the walls of hypocritical society, making the ready-made a corrosive enigma for the mind. And it is the same solvent that for centuries has diluted the thoughts of so many who have stood before the Mona Lisa, an enigmatic figure “smiling under a mustache” that he does not materially have, but which Duchamp provided for her by interpreting the popular saying. Thirty years earlier, a celebrated caricaturist, Sapeck, had drawn the Mona Lisa while smoking a pipe at the 1883 Arts Incohérents exhibition, not only burning poor Duchamp on the spot but demonstrating, we might say today in hindsight, the difference between humor and irony. And it is to the genius of the Romantic thinker Friedrich Schlegel that we owe this fundamental clarification not to reduce irony to a joke, since it almost always releases a tragic hint: “Irony means nothing more than the self-surprise of the thinking spirit, which often results in a silent smile; but even this smile of the spirit hides, however, a deeper meaning, another higher meaning which, not infrequently, contains within itself a more sublime seriousness beneath a serene surface.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.