In Praise of Beauty: twenty masterpieces to celebrate one of Italy's most beautiful museums

How could one integrate the collection that engineer Amedeo Lia, a fine and passionate art collector, donated in its entirety to the City of La Spezia in 1995, allowing the city to open the rich museum that now bears his name? This question is proposed to be answered by the exhibition L’elogio della bellezza (The Praise of Beauty), which brings to the Ligurian city twenty paintings from as many museums in a sort of ideal continuation of the work that enabled Lia to assemble one of the most important private collections at the European level, as well as probably the main one for gold backgrounds, which constituted perhaps his most constant and precious “fixation.” All to celebrate, albeit a few months late, the 20th anniversary of the opening of the Lia Museum, which began welcoming the public on December 3, 1996. Of course: one could reproach the curators, Andrea Marmori and Francesca Giorgi, for having chosen a title that includes that term, “beauty,” so much abused nowadays (and the more a term is abused, the more caution should be exercised in using it). For rather than beauty, a noun that means at once everything and nothing, one could speak of intuition, passion, preparation, intelligence, foresight. Well, patience: an exception will be granted to the reasons of marketing.

A dispensation that will be gladly granted, however, because we are not dealing with a vacuous celebration, but with a meritorious operation, which redeems the Lia Museum from a couple of disappointing exhibitions that have taken place in recent times, and also because it helps the visitor to become familiar with the figure of a collector who wanted to donate his collection to his adopted city in order to avoid its possible future dispersion (and above all to make his fellow citizens participate in his successes, a goal worthy of any enlightened entrepreneur), and finally because the “additions” not only denote those “assonances” with the works in the Lia collection that the curators aimed for, but they are also well placed in the context of the museum space that houses them, as if the panels prepared to welcome them were waiting for nothing more than them. “Guests of quality and family,” then, scattered along a path that is offered to the visitor from a novel perspective: for theIn Praise of Beauty, in fact, one enters from the staircase of the former convent of the friars of San Francesco da Paola, the place that the municipality elected in 1995 as the seat of the Amedeo Lia Museum, and one arrives directly in the hall of the gold funds passing through thearchaeological antiquarium (one thus skips the rooms on the first floor, those that house liturgical objects and miniatures: we will pass through them before leaving).

Almost an entire wall, the one at the back of Room IV, is dedicated to the Five Saints (Francis, Thomas, Catherine, Jerome and Louis of Toulouse) by Neri di Bicci (Florence, 1418/1420 - 1492) arriving from the Accademia Gallery in Florence: the work stands out on a long panel that is also gilded (great attention is paid to the colors of the settings that recall the characteristics of the works or periods to which they refer) and, showing a close adherence to the manner of his father Bicci di Lorenzo, introduces us to the next room, the fifth, that of the Quattrocento. There we find, in addition to the St. Jerome by Bicci di Lorenzo himself (but the attribution is disputed: it could be a work by the young Masaccio), paintings that attest to the transition from Late Gothic to Renaissance, with particular reference to Tuscany and northern Italy: a predella compartment with the Marriage of the Virgin by Beato Angelico (Florence, c. 1395 - Rome 1455) enriches the evidence of this transitional phase, while at “things already done” are dropped two splendid panels by Ambrogio da Fossano known as il Bergognone (Fossano, 1453 - 1523), a St. Agatha and a St. Lucy (note, in the latter, the unusual detail of the eyes stuck in a sort of skewer) once parts of the Polyptych of St. Bartholomew and now preserved at the Carrara Academy in Bergamo. They are on blue panels, like the sky that took the place of the gold background in the Renaissance, and they are entrusted with the task of fruitful dialogue with a Saint Joseph located on site and also, like the two Bergamo saints, assigned to the advanced stages of the artist’s career.

|

| The Hall of the Golden Grounds |

|

| Neri di Bicci, Saints (c. 1444-1453; tempera on panel, 130 x 89 cm; Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia) |

|

| Ambrogio da Fossano known as il Bergognone, Santa Lucia (c. 1500-1520; tempera on panel, 60 x 55 cm; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

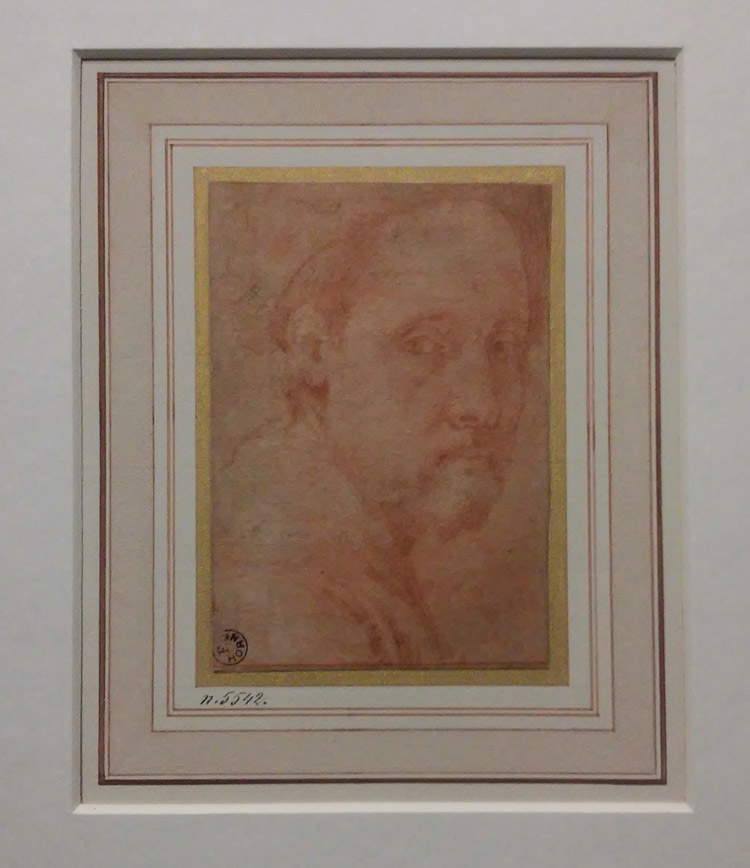

Entering the 16th-century room are what are in all likelihood the most interesting loans in the exhibition. Between the two works by Sebastiano del Piombo in the permanent collection, the Birth and Death of Adonis, anAdoration of the Shepherds by Jacopo Bassano (Bassano del Grappa, c. 1510 - 1592) makes its appearance, completing the wall dedicated to the Veneto, while on the adjoining one, reserved for the Emilians, appears a sumptuous work by Dosso Dossi (San Giovanni del Dosso, 1474 - Ferrara, 1542) from the Galleria Borghese in Rome, a Diana and Callisto that depicts the topical moment of the mythological episode (Diana’s discovery of Callisto’s nudity) and transports the viewer into an almost dreamlike dimension, with this landscape opening ideally continuing that of the Venetian painters. Particularly intense (also because it is set up in a small room thrown into the half-light) is the comparison between theSelf-portrait by Pontormo (Pontorme di Empoli, 1494 - Florence, 1557) belonging to the permanent collection and the drawing from the Horne Museum in Florence, another Self-portrait by the leader of Florentine Mannerism: the spontaneity with which the artist drew himself, pensive and melancholy, is the same as that found in the painting, the last acquisition in Lia’s collection.

|

| The Hall of the Sixteenth Century |

|

| Dosso Dossi, Diana and Callisto (c. 1529-1530; oil on canvas, 49 x 61 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Jacopo Bassano, Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1545; oil on canvas, 93 x 140 cm; Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia) |

|

| Pontormo, Self-Portrait (1530-1532; red pencil on white paper tinted pink, 12.1 x 8.2 cm; Florence, Museo Horne) |

Leaving the sixteenth century behind with another exceptional loan, Bramantino ’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Milan, c. 1465 - 1530) from the Castello Sforzesco, we come to the seventeenth-century corridor where ample space is given to the art of theage of the Counter-Reformation: the religious patheticisms and anxieties of the time, which indeed find little space in the permanent collection, are evoked by three works. These are a St. Clare by Panfilo Nuvolone (Cremona, 1581 - Milan, October 27, 1651) and especially a small Christ Crucified by Annibale Carracci (Bologna, 1560 - Rome, 1609) and a Madonna and Child by Ludovico Carracci (Bologna, 1555 - Rome, 1619). It is in particular the works by the two Bolognese cousins that strike the viewer and invite reflection on the two “souls” of Counter-Reformation art: the meditation on pain induced by the suffering Christ on the cross silhouetted against a somber sky, and the closeness to the faithful of the Christian pantheon depicted in all its humanity, which in Ludovico’s painting is substantiated in a Child wincing and throwing himself toward a rose that his mother shakes to make him play. The exhibition then continues with works by Guercino, Giulio Cesare Procaccini and, on the upper floor, a still life by Chardin that is measured against the similar paintings in Room XIII, a bronze Clement X, by Bernini, enriching the room of bronzes and marbles, and a Madonna by Matteo Civitali. One then descends and reaches the ground floor for the conclusion in the halls of miniatures and liturgical objects.

|

| The 17th-century corridor |

|

| Annibale Carracci, Christ Crucified (c. 1594; oil on canvas, 33.8 x 23.4 cm, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Ludovico Carracci, Madonna and Child (oil on canvas, 114 cm diameter; Rome, Pinacoteca Capitolina) |

The exhibition could have been accompanied by an effective didactic apparatus that could have illustrated the curators’ choices and helped to better context ualize the loans in the exhibition context: in this respect the exhibition fell short. Nonetheless, the operation is to be welcomed, also for another aspect, in addition to those listed above: it is an exhibition that affirms the role of the Lia Museum as a major European player, at the center of networks of collaborations with other museum institutions that have often had the Lia’s name marked on the list of lenders of important exhibitions, even at the international level, or have seen it support projects of various kinds, or have seen its director, Andrea Marmori, be part of scientific committees of considerable depth. Again, the selected loans have the merit of emphasizing Amedeo Lia’s taste and main artistic passions: space, therefore, to gold collections, as already mentioned, but also to small objects of ancient art, medieval codices, and seventeenth-century painting. Just missing is eighteenth-century vedutismo, a genre that abounds in Lia’s collection and to which an entire room in the museum is dedicated.

Not a usual exhibition, then. And, if we want, not an easy exhibition either, but this very feature marks a point in its favor: it induces us to walk through the halls of the Lia more than ever with the eyes of the collector who wanted to collect pieces of exceptional value and then make a gift of them to the city. It spurs us to walk slowly through the halls of the museum, to think about what choices dictated the purchase of a painting, a sculpture, a liturgical object, whether Lia had ever thought of completing certain parts of the collection or whether they seemed to him to be sufficient, whether there were authors that the engineer strongly wanted for his own collection and that he never managed to achieve. Answers that often come from the paintings themselves, hidden in the folds of a robe, behind the decoration of a gold background, among the objects scattered over a still life table, in the looks of a character. And just as often they come from the affinities and contrasts with the paintings in the Lia Museum’s permanent collection, which, withIn Praise of Beauty, probably reaches one of the high points of its short but already intense history.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.