by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 08/03/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Painting and Drawing as a Grand Master: the Talent of Elisabetta Sirani,' in Florence, Uffizi Gallery, March 6 to June 10, 2018.

Short and tragic was the parabola of the star ofElisabetta Sirani (Bologna, 1638 - 1665), an artist of exceptional virtue, daughter of that Giovanni Andrea Sirani who, from being a pupil of Guido Reni, became his closest and most faithful collaborator, and a painter capable of astounding her contemporaries thanks to an elegant and modern art, innovative and versatile, capable of measuring herself with always happy results in both profane and sacred subjects, in portraits as well as in allegories. A short but intense and luminous parable: when she passed away just 27 years old, taking away an adorable daughter from her poor ailing father, who would outlive her by only five years, and a rare talent to the art world, her fame was already shining, patrons couldn’t wait to get one of her paintings, colleagues admired her and liked to discuss art with her, others apparently envied her, and her name was among the best known in her native Bologna. But her genius also reached across the Apennines and fascinated the rich and cultured Florentine clientele: the Medici, in particular, could not do without her marvelous paintings. It is said that on one occasion, in the presence of Cosimo III, Elisabeth astonished the then 22-year-old prince by quickly and promptly painting one of the children in the allegory of charity that appears in the canvas with Justice, Charity and Prudence now owned by the Municipality of Vignola, so much so that the future grand duke was persuaded to commission a Madonna and Child from her immediately.

The link between Elisabetta and Florence is one of the many themes underpinning the exhibition Painting and Drawing as a Grand Master: the Talent of Elisabetta Sirani, running at the Uffizi Gallery until June 10, 2018 and curated by Roberta Aliventi and Laura Da Rin Bettina. It was her first biographer, Carlo Cesare Malvasia (Bologna, 1616 - 1693), who wrote that Elisabetta had a “way of drawing like a grand master and practiced by few, nor less so by her father himself.” Malvasia himself, after all, had been an eyewitness, having seen her several times at work on a sheet of paper, tracing, with that promptness that was recognized as one of her most formidable gifts, a few marks capable of giving shape to a figure, then completed with the tip of a brush dipped in diluted ink so as to create a sort of "speckled drawing." And it was Malvasia again who started the myth of Elisabetta Sirani: with vivid transport and writing steeped in emotion and sincere sorrow, made all the more profound by the fact that the great Bolognese writer was a friend of the Sirani family, in his Felsina pittrice Malvasia spared no adjectives in singing the young woman’s praises, calling her “courteous in hearing, charming in her replies, gentle in her features,” “lovable beyond measure,” “worthy of eternal fame,” and again “prodigy of art,” “gem of Italy,” “sun of Europe,” “heroine painter.” “Heroine” is a term certainly dictated by Malvasia’s particular fondness for the artist, but which nevertheless does not seem so out of proportion when compared to the actual historical role played by Elisabetta Sirani. Beyond the mythicizations to which her figure has been subjected, and to which her high level of education and talent, the sweetness of her temperament and the beauty of her appearance have contributed, it is necessary to emphasize how Elisabetta Sirani represented the case of a woman who in the seventeenth century found herself having to manage her father’s workshop alone (and, moreover, very young), and, above all, it is necessary to note that the young woman is listed as a professor in the registers of the Accademia di San Luca, and that she animated a kind of artistic coterie, all female, of which her sisters Barbara and Anna Maria, also painters, and several other young artists were part. “The main significance of the figure of Elisabeth,” wrote the scholar Adelina Modesti in a contribution published in 2001 in English, “lies in the professionalization of women’s artistic practice, through the development of a method of professional training for women, outside the traditional model of the mentor man (female artists in fact learned their craft through male colleagues: fathers, husbands, brothers), and thus in having created broad avenues for female cultural production and female transmission of knowledge, having been an educator and model for the next generation of women artists.”

|

| Hall of the exhibition Painting and drawing as a grand master: the talent of Elisabetta Sirani |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Painting and drawing as a grand master: the talent of Elisabetta Sirani |

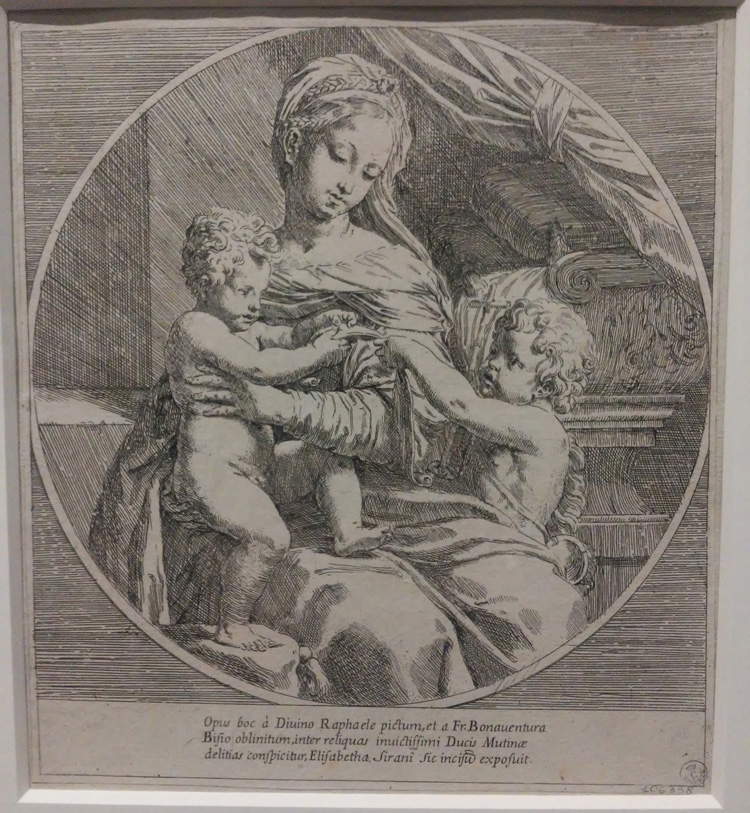

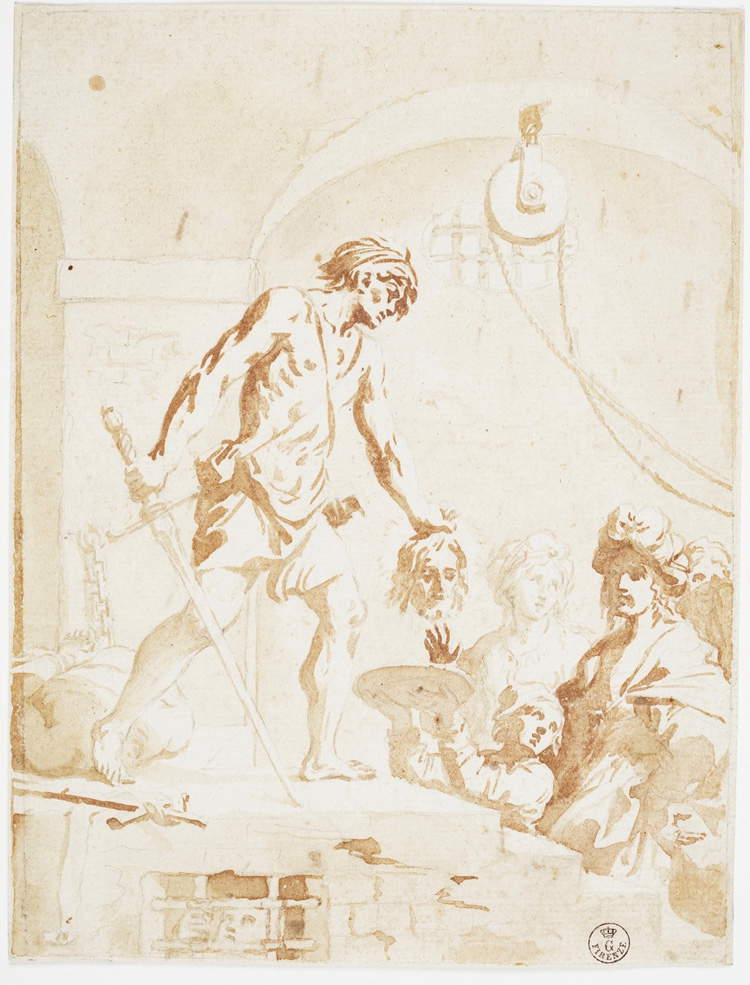

In order to historically frame the figure of Elisabetta Sirani, the Uffizi exhibition, which starts from the Sala Detti, begins with a series of works that offer an icastic testimony to the wide network of patrons that the Sirani family was able to build, and of which the young artist took advantage, satisfying the requests of a cultured, attentive, demanding and refined clientele, which was also helpful to Elisabetta in acting as her liaison with the Medici court. We thus find a sequence that introduces us to the figures who were significant to her, starting with Carlo Cesare Malvasia himself, for whom Elisabetta executed the etching that opens the exhibition and which translates into engraving an Immaculate Virgin who had previously been painted by her father for the church of San Paolo in Monte in Bologna: the Madonna, with her long hair loose on her shoulders, her hands crossing as if by instinct at breast height and her serene gaze turned toward the ground, is distinguished by that immediate, free, almost impulsive sign that characterized all of Elisabetta Sirani’s graphic production. The work that the public encounters immediately afterwards, a further etching, depicting a Madonna and Child with St. John, bears a dedication to Friar Bonaventura Bisi, a Franciscan minor as well as a valid painter specializing in copying ancient works, and above all the first author of a eulogy to the young woman: dates back to 1658, when Elisabetta was still in her early twenties and Bisi, on terms with Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici, sent a letter to the prelate with a drawing of Elisabetta enclosed, asking him to “see this little sketch for being by the hand of a very talented putta, et è la figlia del nostro Sirano da Bologna d’età d’anni 19 in circa, e dipinge da omo con molto prontezza et invenzione.” The cardinal must have evidently appreciated the friar’s homage given that, from that moment on, relations with Elisabetta would not be interrupted: this is also testified by two drawings, a Decollazione di san Giovanni Battista and a Ritratto di giovane, which the Bolognese nobleman Ferdinando Cospi (who was also distantly related to the Medici) sent in 1662 to Leopoldo de’ Medici himself, stating that “la figliola [....] in hoggi è tenuta maestra et è lei che mantiene co’ sua lavori tutta la sua numerosa famiglia, anco con avanzo in capo al anno essendo il padre affatto impotente et il Volterrano che ha visto le sue opere e lavorare le disse esser il meglio pennello che fusse ora a Bologna”.

The fact that she was recognized as having “da omo” qualities, that she was considered a “maestro,” and that even Baldassarre Franceschini, the “Volterrano” to whom Cospi refers in his missive, considered her “the best brush” in Bologna, might already constitute sufficient details in themselves to give us a first idea of what Elisabetta Sirani’s abilities were: to complete this idea comes, therefore, the first painting in the Florentine exhibition, a very refined Galatea also executed for the Marquis Cospi, signed and dated on the edge of the cushion, according to that ingenious taste that led Elisabetta to affix her signature in the most unthinkable areas of her paintings. This is the last work that the young woman executed for the nobleman: it gives us a Galatea with adolescent features, with a headband on her head to give order to a modern-cut hair, with her veil stirred by the wind to form a large vermilion circle that picks up on a motif widely practiced by Francesco Albani and later becoming part of the typical repertoire of many painters from Bologna, and depicted in the act of plowing the sea waves on a bizarre and uncomfortable shell pulled by a large dolphin. A Galatea who is almost an embodiment of the feminine ideal that populates Elisabetta Sirani’s imagination: a girl with sweet features and a petite but shapely and graceful body, who denotes an ill-concealed youthful pride with her gaze somewhere between innocent and mischievous, and who with the studied gesture of her right hand, caught while choosing a pearl from the tray brought to her by the putto, reveals with palpable clarity the delicate gracefulness of her own manners. Completing the list of figures who mediated relations between Elisabetta Sirani and the Medici court comes the portrait of Count Annibale Ranuzzi, another prominent patron of the painter. Bisi, Cospi, Ranuzzi: all intermediaries and agents of the Medici on the Bolognese market, able to move with skill as much among antique art dealers as among the workshops of contemporary artists. They negotiated prices, searched for and found the most valuable objects, maintained relations with the most established artists and in parallel sounded out new talents, and once they had assessed the goodness of a young man they followed his progress and then informed the illustrious correspondents, advocating the purchase of their works.

This was also the case for Elisabetta, who in the portrait of Annibale Ranuzzi makes use of a few signs in red stone, a technique she did not use much, to draw a study that fixes on paper the nobleman’s stern gaze, a clear expression of a sullen temperament that is also evident from the letters written in his own hand. A rigidity of character that is nevertheless diluted in the letter sent to Leopold de’ Medici on August 28, 1665, the day of Elisabeth’s death. The count was the first to alert the cardinal of the tragic event, which threw all of Bologna into despair, as the artist “so much grew every day in virtue, that one could hope for great success.” The rest of the letter let out a very dismayed participation in the mourning: “if V.A. has conjuncture to see any of his things lately done, he will still know the considerable improvement that was always there. I know that the humanity, or the virtuous genius of V.A.S. cannot but be displeased by such news, nevertheless I make it known to you so that it may seem to me considerable, and so that you may not be surprised that I do not give you an account of his designs, while at the point that I hoped to show them to Mr. Gio. Andrea, somewhat relieved from the pains of gout, the poor man was inconsolably assailed by this travail.”

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Immaculate Virgin (etching; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist (etching; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1662; black stone, brush and diluted ink on paper; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Galatea (1664; oil on canvas; Modena, Museo Civico d’Arte) |

|

| The signature on the Galatea |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Portrait of Annibale Ranuzzi (red stone on paper; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

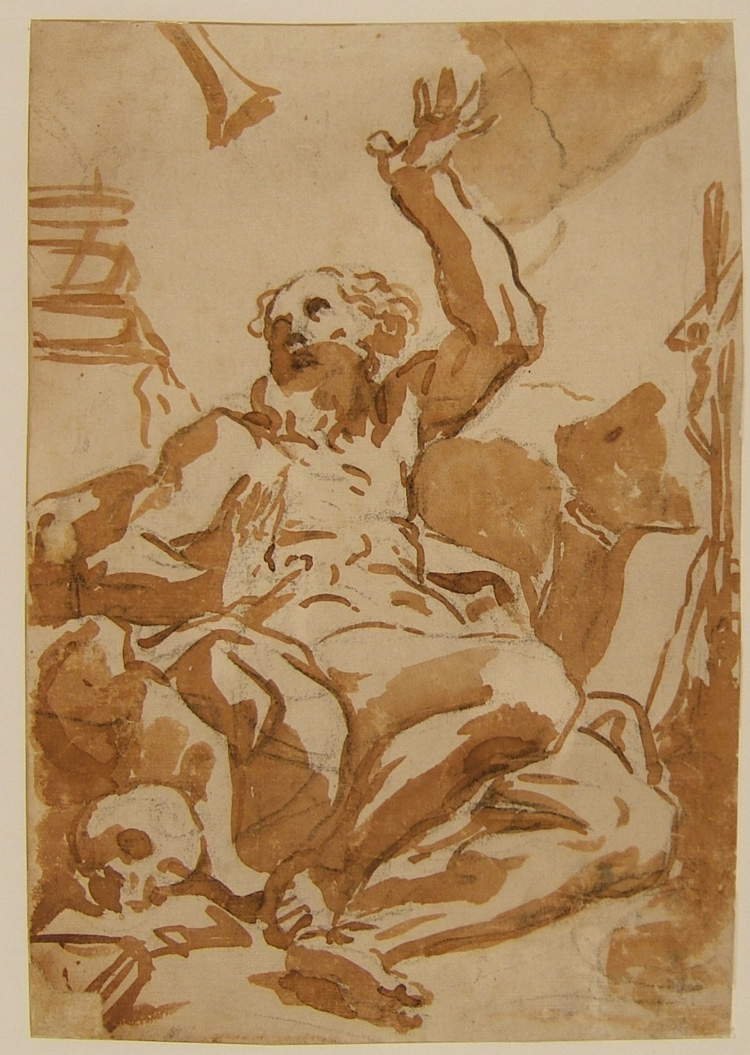

The second section of the exhibition aims to explore, with careful stylistic investigation, the peculiarities of the Bolognese artist’s graphic production. An interesting novelty is represented by a Sacra famiglia con sant’Anna e san Gioacchino (Holy Family with St. Anne and St. Joachim), which is exhibited in Florence for the first time with the attribution to Elisabetta Sirani (until now it had been referred to Domenico Maria Canuti): it is the study for the painting, also on display in the exhibition, made around 1662 as a variant of an earlier painting executed for a jeweler in Bologna. It is a sacred conversation in which the characters participate with emphatic gestures, and that the painter’s attention had focused mainly on the gestures and attitudes of the characters (the most eloquent detail in this regard is the gesture of St. Joachim, grandfather of Jesus, who playfully hands him a pair of cherries) is evident from the stroke that becomes more pronounced and studied near the hands and eyes of the characters, which Elisabetta Sirani builds with that quick and free sign that moved many of her contemporaries to wonder, not least because the prettiness and vigor of the lines were considered purely masculine qualities. The artist’s production does not abound in sheets marked in black stone as the study for the Holy Family does: nevertheless, Elisabetta Sirani excelled in this technique as well. It is necessary, however, to observe the studies with diluted ink in order to have a more solid and complete idea of the Bolognese artist’s skills: a Saint Agnes and a Saint Jerome that the public encounters in quick succession constitute two admirable essays of invention and speed of execution. After sketching the figures, Elisabetta would take a brush, dip it in diluted ink, and add backgrounds that gave her a way to study her figures’ chiaroscuro, shading, and highlights. In the Saint Agnes, for example, ink is used to set the dark background of the composition and to emphasize the shadows, as well as the folds of the draperies. The same is true of the sheet with Saint Jerome, from which it is evident how the rapid brushstrokes follow the contours of the figure of the saint and the rocks to delineate chiaroscuro contrasts.

There is also room for etchings: particularly interesting is the etching taken from the Mater dolorosa painted in 1657 for the Oratorian father Ettore Ghislieri, as the inscription accompanying the image in the printed work also attests. A classic theme of Marian iconography, that of the grieving Madonna with the angels bearing the symbols of the Passion, is declined by Elisabetta Sirani in terms of a balanced and composed, yet total, emotional participation in the sorrow: of great intensity is the detail of the little angel who, kneeling in the right corner of the composition, weeps rubbing his eyes with his hands. A composition that, noted scholar Vera Fortunati, effectively gives substance to Oratorian pedagogical principles, founded on playfulness, happiness, and vitality: thus, the clear and bright chromatics, and the affection conveyed by the angels surrounding the Virgin, help to better endure pain and comfort the devotee in his oration. The meticulous brushstroke that follows the forms finds an immediate echo in the etching: the sign, which even in the etching becomes minute, sometimes becoming denser and more marked, sometimes finer and more delicate, richly recreates the shadows and chiaroscuro of the painting.

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Holy Family with St. Anne and St. Joachim (1662; black stone on paper; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Holy Family with Saint Anne and Saint Joachim (ca. 1662; oil on canvas; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Saint Jerome (black stone, brush and diluted ink on paper; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Sant’Agnese (black stone, brush and diluted ink on paper; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Mater dolorosa (1657; oil on copper; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Mater dolorosa (1657; etching; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Comparison of the two versions of Mater dolorosa |

A small group of oils is entrusted with the task of introducing the public to the workshop of the Sirani family, from which came out works of the highest quality, which promoted (and, for that matter, could not have been otherwise) a suave classicism of Rhenish descent declined in less solemn and compassed tones and, conversely, marked by a warmer sentimentalism. A typical example of this manner is the Madonna and Child with St. John, owned by the Cassa di Risparmio di Cesena and whose attribution oscillates between John Andrew and Elizabeth, such is the closeness of manner: the playful movement of the little Saint John (the almost tactile rendering of the flesh tones in the half-light and the wavy ringlets verges on virtuosity) is answered as much by the attitude of the Child, leaning toward his cousin to join the game, as by the good-natured gaze of Mary, who curiously holds her son with her hands crossed, almost in a gesture of prayer. Again, a drawing by Giovanni Andrea for a more composed work on the same theme was taken up by Elisabetta, who translated it, turning it, however, into a Holy Family with St. John, in oil on copper (although the attribution is uncertain, since it could also be the work of her younger sister Barbara) and etching. The self-portrait loaned by the Pushkin Museum in Moscow closes the section: Elisabeth is portrayed dressed in a silk cloak testifying to the status she had achieved, with the gold chain around her neck, a symbol of painting (in Cesare Ripa’sIconology it is clarified that gold represents the nobility of the painter’s craft, and the mask that was to hang from the chain, hidden in Elisabeth’s self-portrait, served “to show that imitation is joined with painting inseparably”) and with sculptures and books behind her as symbols of culture.

The exhibition concludes in the Hall of the Fireplace, where the public will find a number of works with allegorical subjects: these are undoubtedly the most interesting paintings, since less conventional themes gave Elisabeth the opportunity to try her hand at her works with more freedom and the inventive originality that was her own and that her contemporaries unanimously recognized. The exhibition also displays the aforementioned canvas with Justice, Charity and Prudence, now in Vignola, which the artist painted for Cosimo III de’ Medici. It was a celebratory work, entrusted with the task of depicting the virtues that should inspire good government, specifically that of the Medici family over Tuscany: given the importance of the painting, Elisabetta put a great deal of effort into its realization, as the numerous studies that have come down to us testify. The three protagonists of the painting, each equipped with typical iconographic attributes (the children for Charity, with the one on the lower left echoing Cesena’s Saint John, the sword and scales for Justice, the mirror for Prudence) help to give substance to an ideal of virtue that is perhaps muliebre even before being political, and which is reflected in the proud and dignified attitude of the three women (see in particular the pose of Justice), in their beauty that does not yield to prissiness, in the firmness of their gestures and looks. Elisabetta adds her own signature on the buttons of Justice’s blue bodice, and the refined use of including her own name within the most unusual details also recurs in one of the young woman’s last works, the Portrait of Anna Maria Ranuzzi in the robes of Charity, where the artist’s name appears on the right cuff of the protagonist’s dress, sister of that Hannibal Ranuzzi mentioned above: the work, which fits into the vein of allegorical portraits (and where, moreover, the cherry motif returns), was executed in 1665, shortly before the artist passed away.

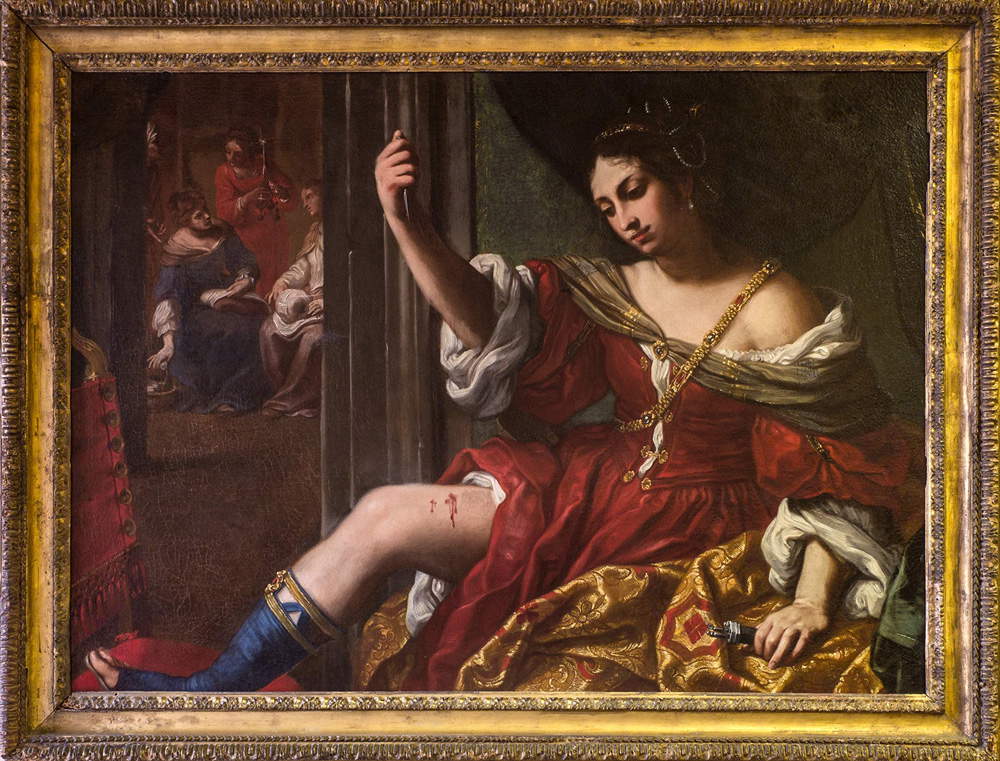

By contrast, the Portia signed on the back of the chair that the artist inserts in front of the Roman noblewoman is from a year earlier: daughter of Cato Uticense and wife of the Brutus who organized the conspiracy against Julius Caesar, Portia took her own life following the death of her husband, having promised him that she would commit suicide if their plan failed. An example of steadfastness, she is depicted by Elisabeth not, as is traditional, at the moment of suicide, but in the act of injuring her thigh to demonstrate to Brutus her conviction in wanting to follow him in his political plots: the artist intended to make a clear claim for the active role of women capable of rising above the subordinate condition that was reserved for them in their time (symbolized by the handmaids in the other room) and demonstrating their equality with men. The taste, typical of Bolognese classicism, for minimizing the most truculent details of the narratives is evident in the woman’s wound itself: little more than a scratch, with two rivulets of blood running down her flesh. Conversely, great attention is given to the rendering of materials: observe the silks, fabrics, golds, and jewelry that Portia wears on her head. The section is completed by a triumphant Cupid, another painting commissioned by the Medici, executed on the occasion of the marriage, celebrated in 1661 (and later revealed to be one of the most unhappy in Medici history), between Margaret Louise of Orleans (the recipient of the work) and Cosimo III: consequently, it is a canvas that sums up the whole range of allegories and symbols proper to a marriage painting. The figure of the protagonist himself, first of all: the god of love represents a clear invitation for the two spouses. And then the six pearls: arranged to evoke the Medici coat of arms, they allude to the name of Margaret Louise of Orleans(margarita is the Greek word for “pearl”). Also, the putto on top of the dolphin, a symbol of pleasantness (for Ripa, “a dolphin carrying a child on horseback” is the icon of the “pleasant, tractable et amorevole soul”), and the wind swelling the cupid’s veil, an auspicious symbol.

|

| Elisabetta Sirani or Giovanni Andrea Sirani, Madonna and Child with St. John (oil on canvas; Cesena, Cassa di Risparmio di Cesena) |

|

| Giovanni Andrea Sirani, Madonna and Child with St. John (black stone, brush and diluted ink on paper; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Drawings and Prints Cabinet) |

|

| Elisabetta or Barbara Sirani, Holy Family with St. John the Baptist (oil on copper; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Allegory of Painting (self-portrait?) (1658; oil on canvas; Moscow, Pushkin Museum) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Justice, Charity and Prudence (1664; oil on canvas; Vignola, City of Vignola) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Anna Maria Ranuzzi Portrayed as Charity (1665; oil on canvas; Bologna, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna Art and History Collections) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Portia (1664; oil on canvas; Bologna, Collezioni d’Arte e di Storia della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna) |

|

| The blood on Portia’s thigh |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Amorino trionfante in mare o Amorino Medici (1661; oil on canvas; Bologna, private collection) |

It comes naturally to one to wonder what other outcomes Elisabetta Sirani’s painting would have touched, had the young woman not been seized by an untimely death: it is rhetorical, yet it is the most natural reaction one feels when faced with her drawings and paintings. However, the public can get an idea by looking at the quality of the works on display at the Florentine exhibition: this is not the first exhibition ever on the Bolognese painter, who has already in the past had the honor of a monograph, but it is a review that, as is typical of exhibitions at the Uffizi devoted wholly or for the most part to graphic art, consistently maintains a very high level, it is supported by a quality scientific project, curated moreover by two very young scholars, and succeeds in keeping the public’s attention high throughout the exhibition (something that does not always happen in exhibitions dedicated to the graphic production of an artist). The absence of a real catalog is partly compensated for by anonline exhibition, accessible on the Uffizi website, with good reproductions, present for all the works, and for the most part accompanied by brief descriptive notes: this is by now a practice shared by all the Florentine museum’s exhibitions of graphic art produced within the Euploos project, and the present one does not deviate from it.

However, it constitutes a peculiarity that characterizes the exhibition on Elisabetta Sirani the presence of paintings, in addition to drawings and prints: more in detail, the review makes comparisons between drawings, paintings and prints that are always precise and alluring, and is in every step extremely consistent with the objectives stated in the opening of the itinerary: To illustrate, as the introduction states, “some key aspects for understanding the figure of Elisabetta Sirani,” namely “her role as a woman artist in the coeval Bolognese cultural context and the fame she enjoyed during her lifetime; the speed and dexterity of execution peculiar to her; her ability to deal not only with sacred themes and portraits, genres considered in the seventeenth century to be the most suitable for women painters, but also with allegorical and historical subjects, often interpreted with unconventional iconographies” and, of course, to provide the public with some tools to deepen their knowledge of one of the most interesting personalities of the entire seventeenth century. It is worth noting that the curators have made a small selection, since the exhibition consists of thirty-three works, but it is highly representative of Elisabetta Sirani’s biographical and artistic journey, and even useful for reconstructing the historical context in which the artist worked: a far from easy task, and the curators deserve credit for having successfully accomplished this task. Behind each of the works on display is in fact the piece of a mosaic that restores to the public of Painting and Drawing as a Grand Master: the talent of Elisabetta Sirani the portrait of a painter who was up-to-date, modern, ahead of her time, gifted with a natural talent, capable of rivaling her most quoted colleagues and reaching the most cultured, influential and important clientele.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.