The first image that rushes to mind when one thinks of Eleanor of Toledo can only inevitably be Bronzino’s sumptuous portrait in which the splendid duchess of Florence, clad in one of the most material and evocative dresses in the history of art, is depicted together with her son John, in one of the most famous icons of power of the Renaissance. Opulence, wealth, sophistication, haughtiness. This could be summed up more or less as the idea of Eleanor that has become wedged in the collective imagination, and so it will come as no surprise if, still in 2007, Bruce Edelstein wrote, in the entry devoted to the duchess on the Encyclopedia of Women in the Renaissance, that Eleanor “is almost exclusively renowned for her wealth and powerful family connections.” Today we owe in large part to Bruce Edelstein a more accurate and complete picture of Eleanor: the American art historian has been dealing with her for more than twenty years, and there is no scholar who has produced more and better research on the figure of Eleanor of Toledo. Research that, exactly five hundred years after Eleanor’s birth, has found its crowning glory in the major exhibition with which the Uffizi Galleries intended to celebrate the exact anniversary: Eleanor of Toledo and the Invention of the Medici Court, the exhibition curated by Edelstein himself and Valentina Conticelli, which can be visited until May 14 in the spaces of the Grand Dukes’ Treasury on the ground floor of the Pitti Palace, comes last in a year in which many institutions have paid tribute to the duchess, but it is certainly the largest and most comprehensive exhibition ever devoted to her.

At the Pitti Palace, in the residence that Eleanor herself purchased in 1550 after months of negotiations that began in 1549, comes an exhibition that succeeds in summarizing the most up-to-date studies on the duchess to present the public with a dense and complete overview of her figure. The historical image of Eleanor of Toledo has suffered for several reasons: first of all, the fact that ancient historiography is rather sparing on her account, although in the contemporary sources there is certainly no lack of praise from contemporaries. Further circumstances must then be added, above all the fact that Eleonora exercised her political role always in the background and carefully avoiding the spotlight, or again, speaking of her numerous artistic commissions, the fact that payments were often authorized by her husband Cosimo I de’ Medici and vice versa (and consequently, noted already Edelstein in 2000, in his first article on Eleonora, it is not always an easy task to trace the real commissioner of a work), or the little sympathy she must have enjoyed among the Florentines. As a result, the curator explains, “only recently has a path of research been initiated aimed at redefining her specific merits, although there is still a long way to go.” Her specific merits: it is mainly around Eleonora’s works that the exhibition focuses.

A gentlewoman of vast culture, a sovereign of supreme political talent (she was praised by her contemporaries for her prudence, and in more the historian Bernardo Segni, Cosimo I de’ Medici’s ambassador to the imperial court, recalled how the duke himself accepted advice on the management of the state only from his wife and her uncle, Francesco di Toledo, imperial ambassador to Florence), founder of the Boboli Gardens, patron and collector of the highest order who loved to maintain personal and equal relationships with the artists of the Medici court, shrewd administrator of the state’s finances, capable of shrewd investments, very careful in shaping her and her family’s public image, as well as looking after family interests (she contributed determining the careers, and thus the future, of her own children and combining marriage policies for them), without neglecting her weight as a trend setter ahead of the letter and finally, as Chiara Franceschini writes in the catalog, “founder” of “new and modern religious institutions and noble monasteries in the heart of Medici Florence,” as well as patroness “of a devotional art to be enjoyed in the context of a court often on the move between Florence, country residences, Pisa and Siena.” This, in a nutshell, is the portrait of Eleanor that emerges powerfully from the exhibition at Palazzo Pitti.

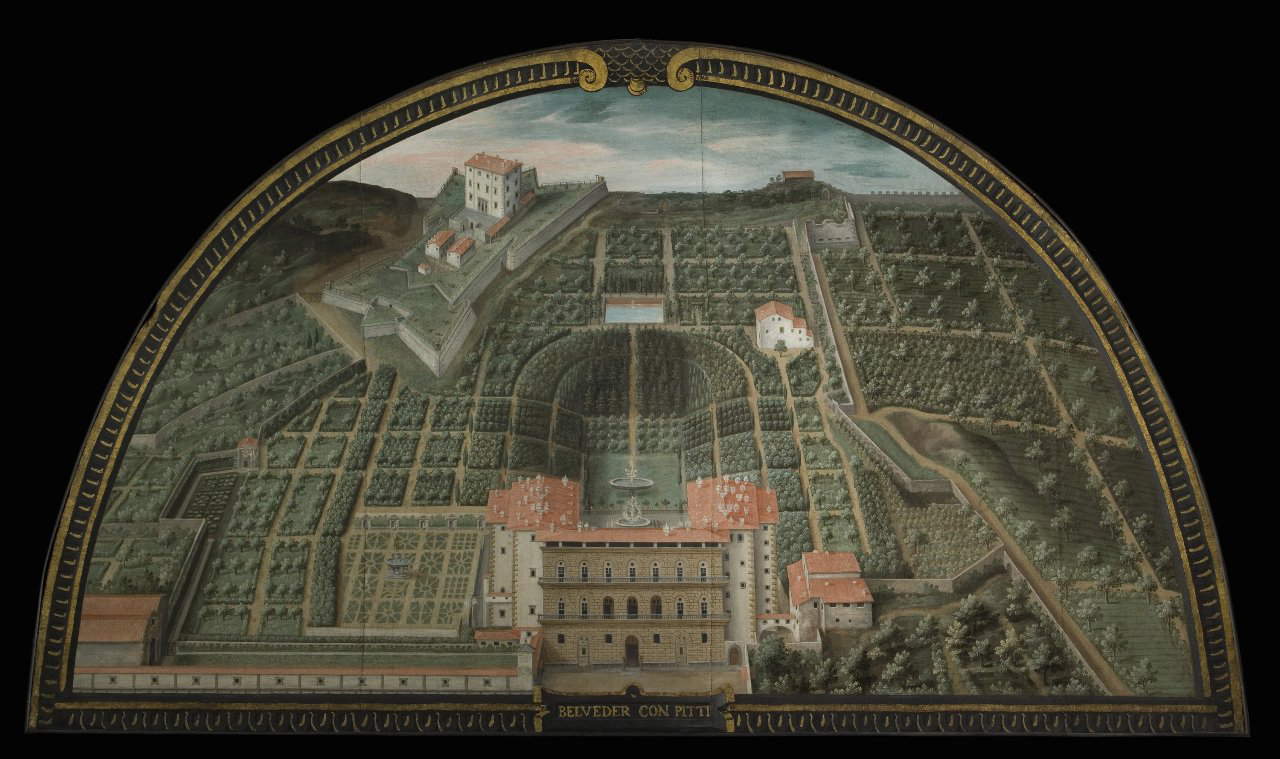

It begins with an introductory section dedicated to what the curator calls “the greatest work of patronage in the artistic-architectural sphere attributable to Eleonora di Toledo,” namely the Boboli Gardens. Welcoming the public is a variant of Bronzino’s celebrated portrait, executed posthumously (in 1584) by Lorenzo Vaiani, known as “lo Sciorina,” who portrays Eleonora together with her son Garzia for the “Aulica Series” of Medici portraits commissioned in 1584 by Francis I in order to be displayed in the Uffizi’s east corridor. The effigy of the duchess is thus linked to her most significant undertaking, evoked by the statues by Valerio Cioli that once adorned the Boboli Gardens, and especially by the canvas by the Flemish Giusto Utens depicting the Belveder with Pitti, painted between 1599 and 1604 with the image of the original design of the Garden elaborated by Niccolò Tribolo after direct indications from the duchess. We then enter the heart of the exhibition with the section presenting Eleanor’s youth and education. The future duchess was the daughter of the viceroy of Naples, Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, and the marquise of Villafranca, María Osorio Pimentel: the portrait of her father, by Titian on loan from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, as well as the bust of Charles V in Carrara marble by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli, are functional in presenting Eleanor’s family background and the ambitions of her father, who, having obtained in 1532 the appointment as viceroy of Naples, promoted a policy of profound renovations for the city, aimed at making it a modern capital (it was under Pedro, for example, that the present-day Via Toledo was opened), a stronghold of the empire from an anti-French perspective, as well as the seat of a culturally refined court, which boasted of hosting such personalities as the poet Garcilaso de la Vega, the theologian Juan de Valdés, and the painters Giorgio Vasari and Pedro de Rubiales. Eleanor was formed in this environment, educated from a very young age in the management of the state (at home she also had the example of her mother María Osorio Pimentel, who replaced Don Pedro at the head of the viceroyalty when he was absent for military campaigns), with the consequence that in her gaze overlapped, writes Carlos José Hernando Sánchez, “the aristocratic reason and its aristocratic strategy, the reason of government concerned with the management of territorial power and the reason of empire, expressed by a dynastic geopolitics that corresponded both to the interests of the Spanish monarchy and to the less effective but legally enforceable interests of the Holy Roman Empire, concentrated in the single figure of Charles V of Habsburg, on whom depended the survival of the young Florentine duchy.” To give an account of the finesse of Pedro’s taste, a fascinating Lucrezia by Leonardo Grazia da Pistoia, a painter much appreciated by the viceroy of Naples, is on display, and likewise Pierino da Vinci’s persuasive river god, a gift from Eleonora to her father for the garden of Don Pedro’s villa in Pozzuoli, bears witness to the passion for the arts that united parent and daughter. Prominent in the same section is Bronzino’s portrait of Eleonora, brought here for the occasion from the Uffizi and displayed next to a portrait of Cosimo, another well-known Bronzino effigy, and some textiles that recall what the duchess wears in the court painter’s painting.

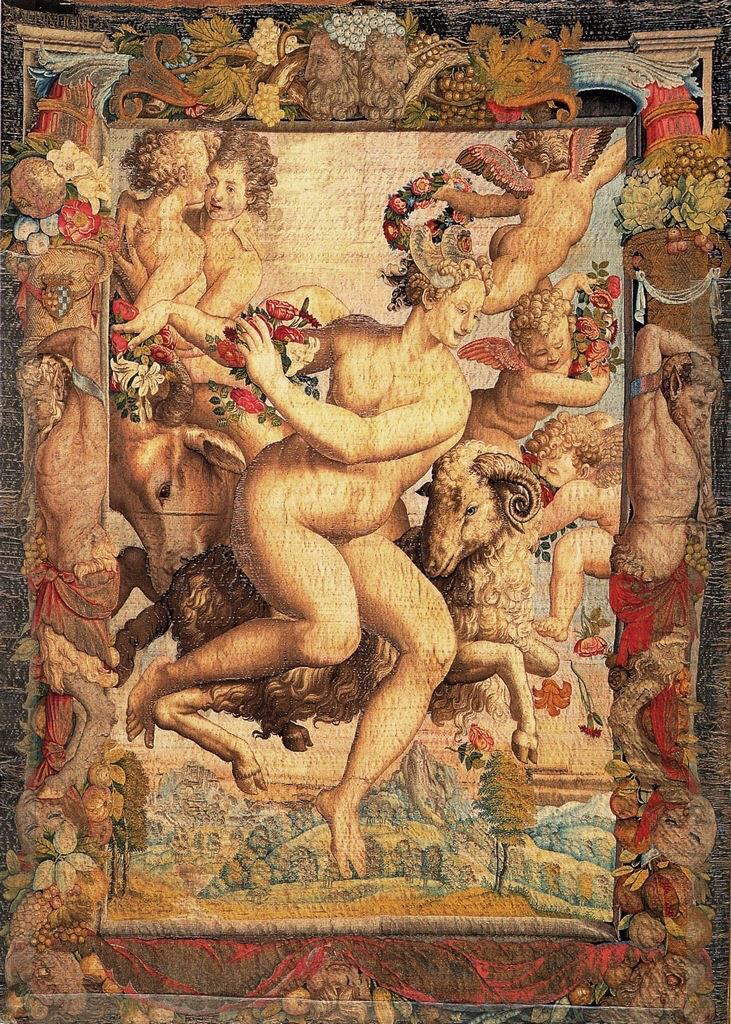

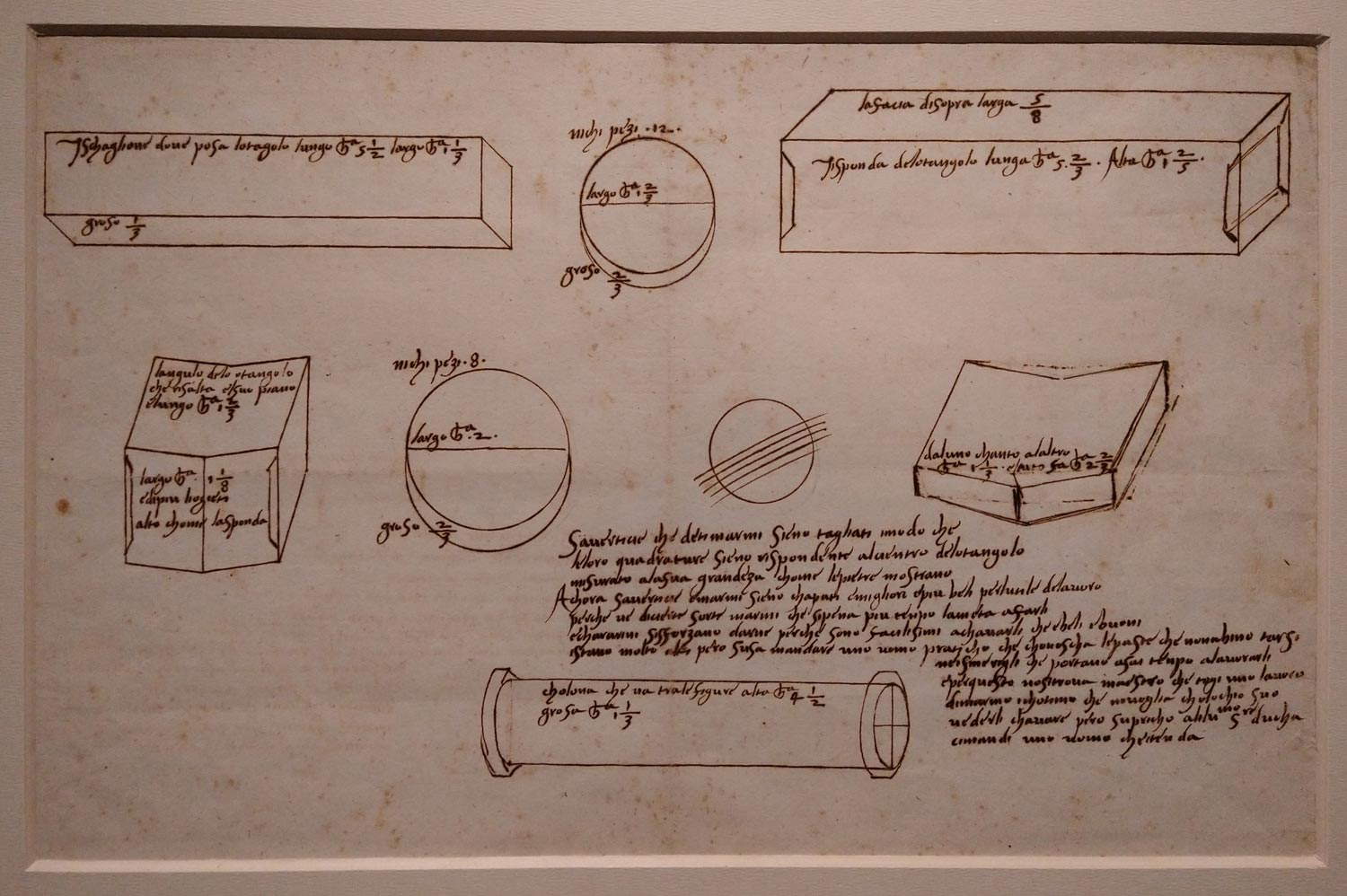

Two white Carrara marble seating bases, on which the image of the Pitti Palace is carved, lead to a sort of coda to the introductory section, to extend the discussion of the Boboli Gardino: in this passage the visitor will be surprised in front of the Villano che vuota un barile, a work by Giovanni di Paolo Fancelli presented in the exhibition as the “first known example of genre sculpture in Western art since antiquity” (it is one of the statues Eleonora requested for the garden), will get into the thick of the work with a sketch by Baccio Bandinelli bearing some notes on the blocks to be quarried in Carrara for the fountain of the Boboli lawn, and will get an idea of the duchess’s programmatic intentions by admiring the tapestries of Spring, by the workshop of Jan Rost from Bronzino’s idea, and of December, January and February from the series of four cloths dedicated to the seasons (workshops of Jan Rost and Nicolas Karcher on cartoons by Francesco Bachiacca), all commissioned by Eleonora. The abundance of fruit and the industriousness of the characters depicted in the tapestries allude, not even too covertly, to the good policies of Cosimo and Eleanor’s government: the visitor has a concrete example of this with the portrait of Luca Martini, the court architect who oversaw the reclamation of the countryside of Pisa, the second city of the duchy, for which the duchess always had significant regards.

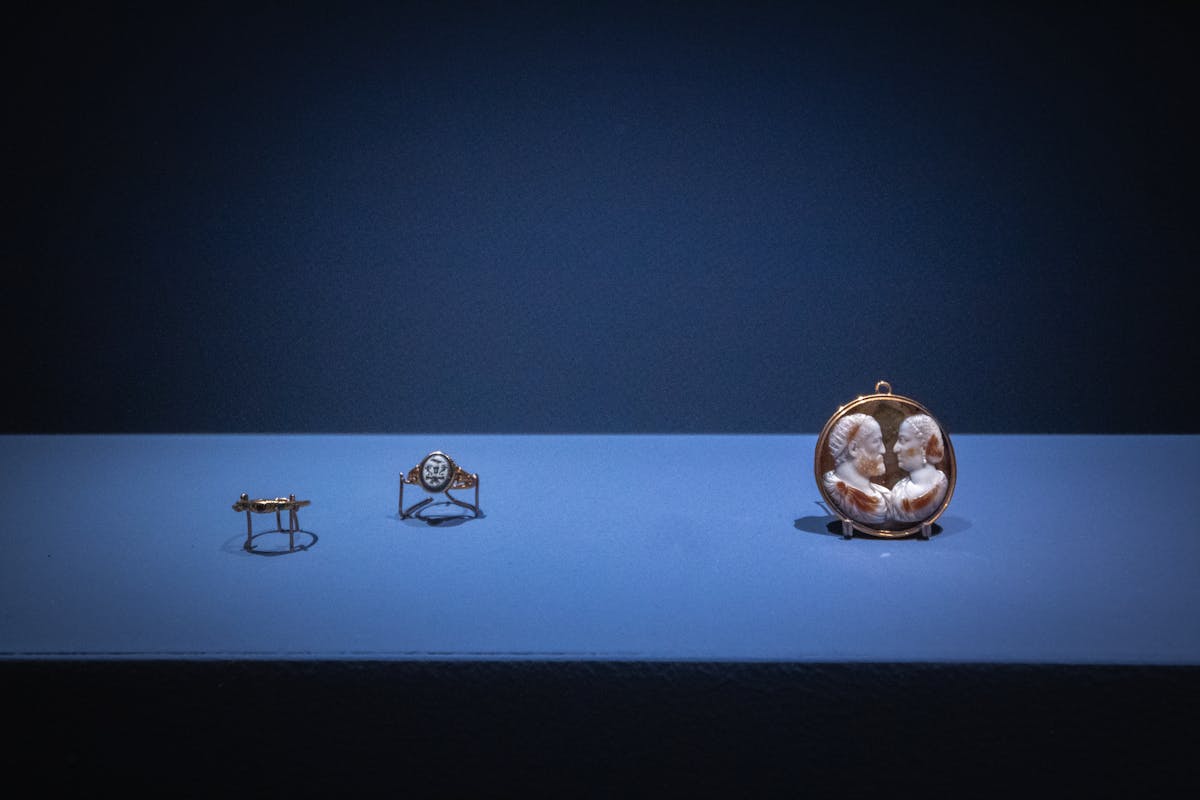

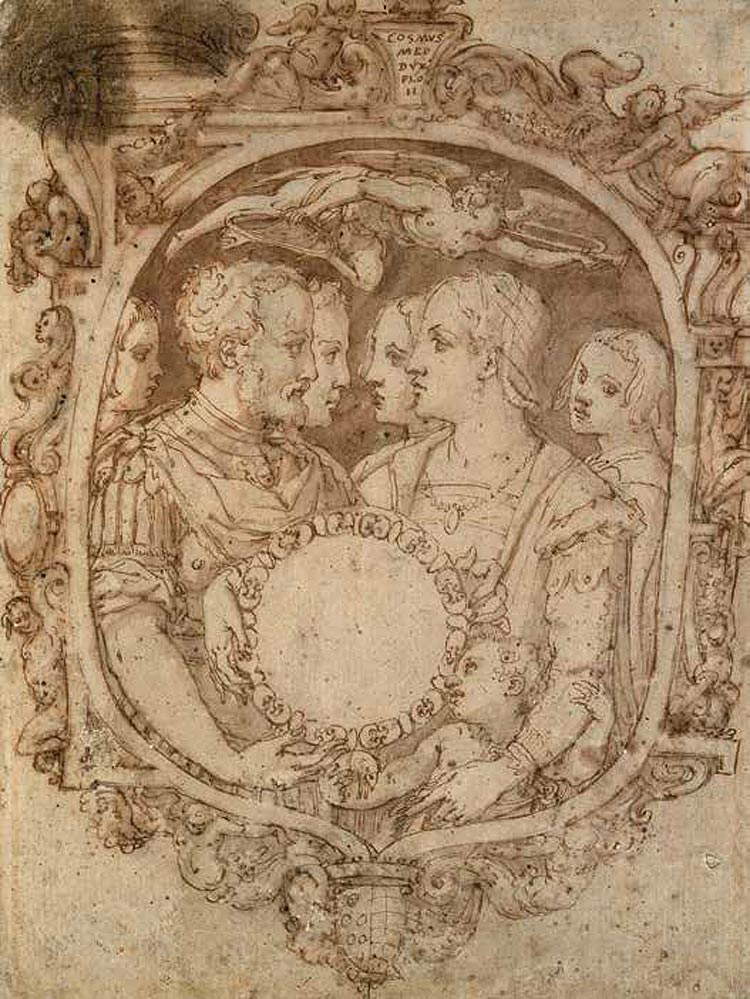

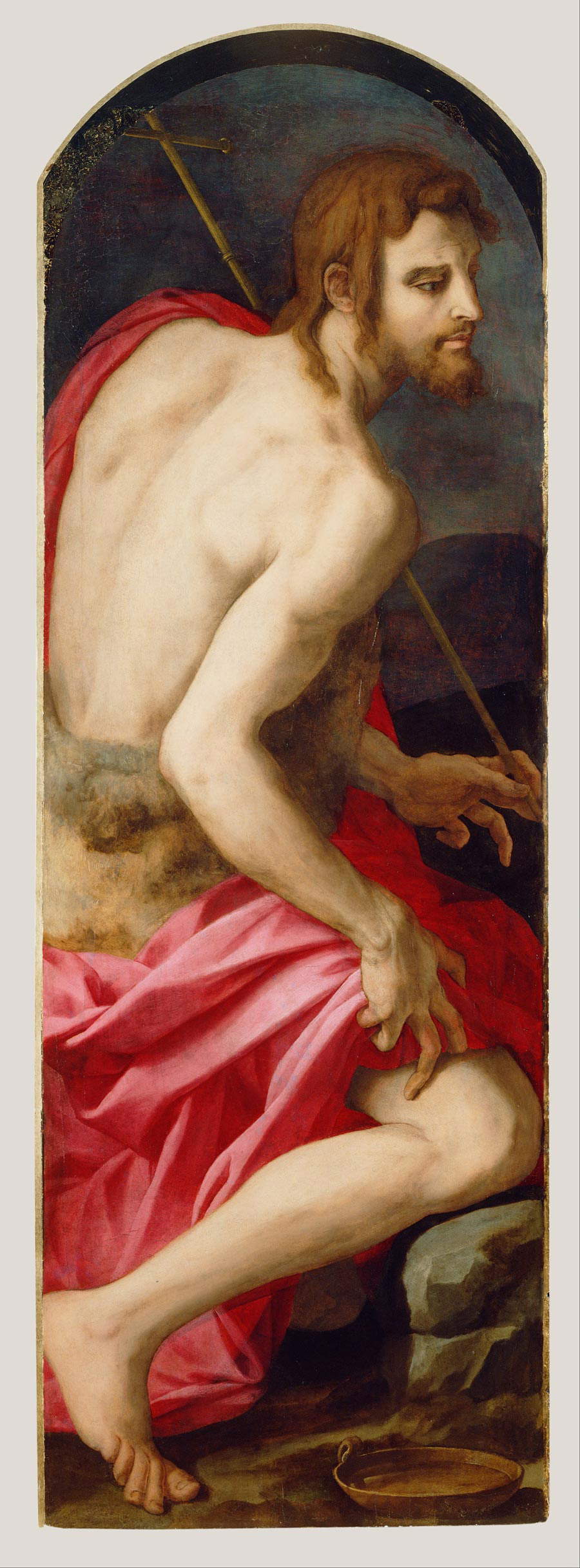

The “invention of the court” that appears in the title of the exhibition is explored in greater depth in the next section, which follows the duchess from the moment of her triumphal entry into Florence in the summer of 1539, a few months after her marriage by proxy in Castel Nuovo in Naples stipulated on March 29, 1539 (it was June 29 when the couple entered the Medici capital). Cosimo and Eleonora first settled in the Medici Palace, but by the following year they had already moved to the Palazzo Vecchio, which was to be radically transformed by the duchess: even today, the itinerary through her apartment is one of the highlights of a visit to the Palazzo Vecchio. The exhibition’s chapter devoted to the transformations of the Florentine court is opened by an excellent comparison between Giovanni Antonio de’ Rossi’s cameo depicting Cosimo, Eleonora and five of their children, a masterpiece of Renaissance glyptics (albeit left unfinished) executed in 1558-1562 to celebrate the ducal couple, and the design that Giorgio Vasari provided to the Milanese carver, on loan from the Christ Church Picture Gallery in Oxford, and continues with some splendid pieces that offer testimony to the image Cosimo and Eleonora wanted and knew how to give of the Medici court, using art as a means of promotion. From Los Angeles comes the St. John the Baptist by the court painter Bronzino, who in ancient times decorated the altar of Eleanor’s chapel in the Palazzo Vecchio, while a little further on theEcce Homo woven by the workshop of Nicolas Karcher to a design by Francesco Salviati stands out as one of the finest products of Florentine tapestry, and not far away the Book of Hours of Eleanor of Toledo gives account of how even in private devotion the models of reference were the highest (the prayer booklet, from 1541, is exemplified by Margaret of Austria’s Book of Hours, from five years earlier). Also on display in the same section are two of Eleanor’s rings, one of them set with a stone from the Roman era, worn by the duchess in a famous portrait preserved in Prague (and unfortunately not present in the exhibition): both bear the symbol of the clasping of the right hands, a symbol of fidelity of the couple. A small appendix on Eleonora’s collecting and, in particular, on her passion for exotic objects, offers the public a Congo call trumpet, stowed in a leather casing with the Medici-Toledo coat of arms (this is probably a gift from the king of Tunis, who sojourned in Florence in 1543), and a mixteca mask from pre-Hispanic Mexico, which most likely came to Florence through Dominican missionaries working in the Americas.

It was mentioned in the opening that Eleanor had shown great care in thinking about her children’s careers: one section, entitled “La fecundissima e iocundissima signora duchessa” (as Paolo Giovio had called her in a letter sent to Cosimo), is devoted precisely to the relationship between Eleonora and her offspring, although it is resolved solely in the display of her portrait (a work by Alessandro Allori dating from 1560, which shows the image of an Eleonora certainly more rehearsed than she appeared some fifteen years earlier in Bronzino’s famous portrait) and of seven of her children (Maria, Garzia, Ferdinando, Lucrezia, Francesco, Giovanni and Pietro), works by Bronzino, Alessandro Allori and their respective workshops. For her children, Eleonora chose names, drawing mostly from those in her family, followed the education by demanding, against the customs of the time, that males and females be educated equally, planned their careers and arranged their marriages. These are stories behind these small portraits on tin, and although the section is a little poorer than the others, they are nonetheless essential works for understanding the public image Eleanor intended for her family: “effigies of individually represented children were quite rare before the end of the fifteenth century and were first commissioned at the court of the Habsburgs,” writes Edelstein, recalling how the duchess had “played a decisive role in introducing this practice to Florence, where Agnolo Bronzino established innovative prototypes that became a model for later generations of the Medici dynasty. These portraits, intended to be bestowed to cement ties with foreign courts, were thus purely political in nature.”

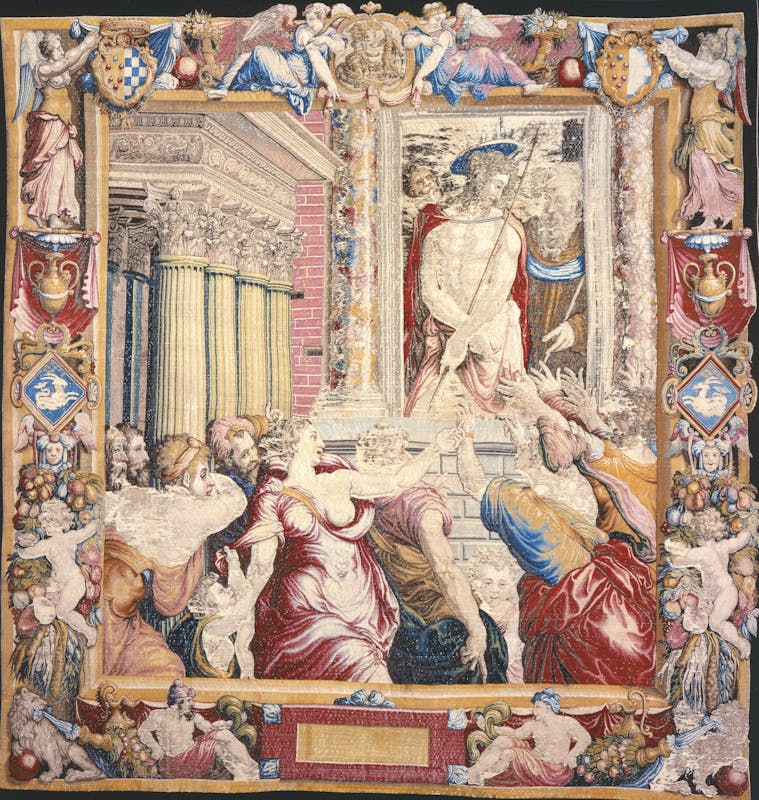

With a leap back in time, the Palazzo Pitti exhibition returns to 1539 and the marriage between Cosimo and Eleonora, tracing the reasons that led their respective families to combine the union between the two (although it was a marriage of interest, it was nonetheless a happy one): at the time of the marriage, husband and wife were twenty and seventeen years old, respectively. Legend has it that Cosimo fell in love with Eleonora after seeing her at a party in Naples, at the time of Cosimo’s first stay in the city, having traveled to Naples as a 16-year-old following his cousin Alessandro, the first duke of Florence, who was going to seal his engagement to Margaret of Austria, the illegitimate daughter of Charles V. That of the sudden falling in love is, however, nothing more than a beautiful legend: it is, if anything, far more plausible that Cosimo and Eleonora had never seen each other before the wedding. And to commemorate the year of their union arrives on loan from the Louvre a drawing by Tribolo, the only evidence of the sets that the architect imagined for Eleanor’s entrance to Florence: a rare foil, not least because often, on similar occasions, all the stage apparatus was thrown away. Next on display is a copy ofApparato et feste nelle noze dello illustrissimo Signor Duca di Firenze et della Duchessa sua Consorte, an account by the humanist Pierfrancesco Giambullari that in nearly two hundred pages provided a meticulous account of the wedding reception, and given to the presses just a month after Eleanor’s arrival in Florence. The political intent was clear: the rapid dissemination of theApparatus, Edelstein writes, “aimed at ensuring that members of the Spanish and imperial court were well informed of the splendor of the Florentine court and its sophisticated artistic, literary and musical culture.” Probably for the same reason, also in 1539, all the music performed for the wedding was printed in Venice: on display is a copy lent by the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice. Then here, in the same room, is the tapestry with Justice Liberating Innocence, another allegory of the qualities of Medici rule, a product of Jan Rost’s workshop on a cartoon by Bronzino, displayed alongside a drawing on the same subject by Francesco Salviati.

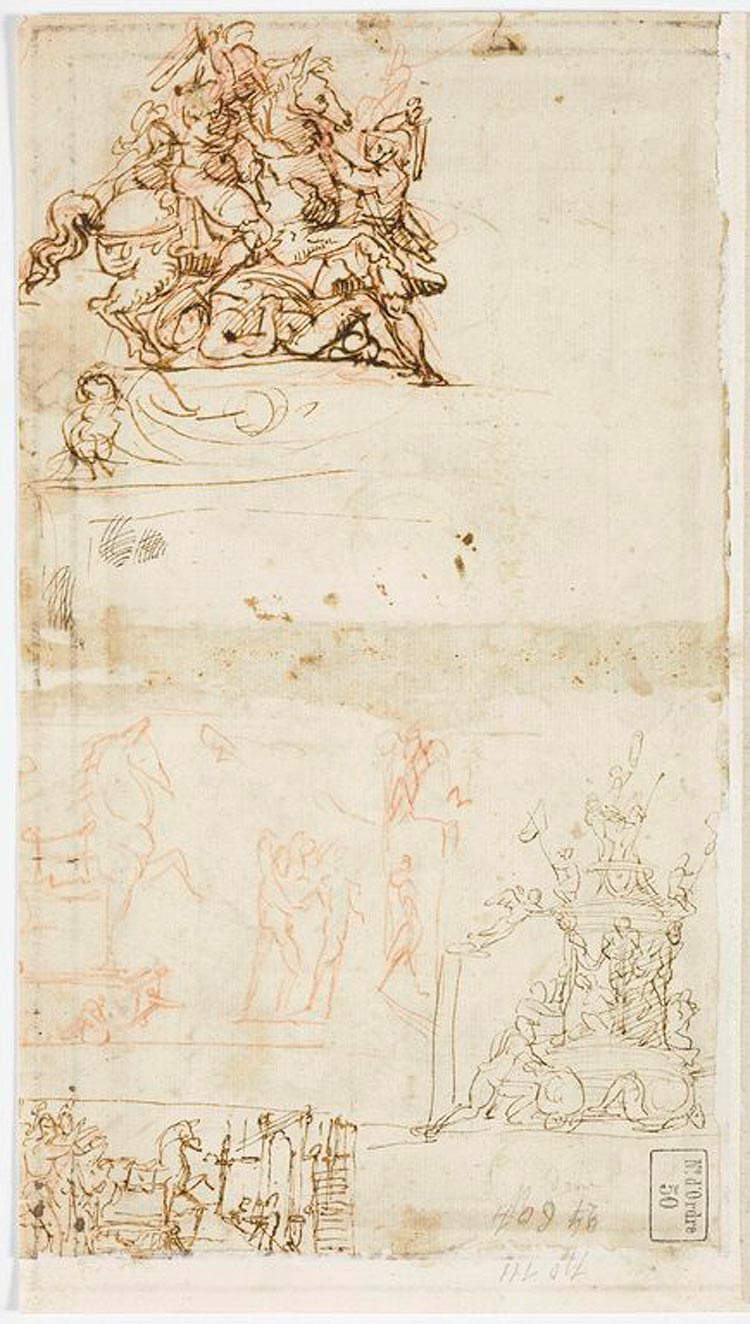

Bronzino’s drawings for various feats of Eleonora and the delightful tempera on parchment by Giulio Clovio, a Croatian miniaturist (real name was Juraj Klovi�?) whom the ducal couple wanted to bring to Florence at all costs (and succeeded: some of his delicate works, such as the Crucifixion with Mary Magdalene or the Rape of Ganymede, splendid tempera paintings with a Michelangelo flavor, are also the result of Eleonora’s direct commission), accompany the visitor to the final room, which focuses mainly on two themes: the transformation of fashion in Florence (the sobriety that had characterized the tastes of republican Florence was definitively abandoned and the era of sumptuous and colorful fashion that looked to Spain opened) and Eleanor’s patronage. In the center is a portrait of Eleanor with her son Francesco, another variation of Bronzino’s image, and around it clothes and jewelry for the chapter on fashion (a woman’s dress from the workshop of Agostino da Gubbio, the court tailor, stands out), and some relevant works to underscore Eleanor’s role as patron of the arts. Singular are the Rime of Tullia of Aragon, perhaps the first work in the history of Italian literature written by a woman and dedicated to a woman, and then there is the portrait of Laura Battiferri, a celebrated poetess who similarly offered her rhymes to Eleanor (with the peculiarity that in her tribute the duchess appears first and Cosimo second), and on to the magniloquent pair of red porphyry portraits of Eleanor and Toledo, the very hard stone in ancient times reserved for royal portraits. Closing is an altarpiece by Alessandro Allori, Jesus and the Canaanite Woman, commissioned by Laura Battiferri and her husband Bartolomeo Ammannati for the Jesuit church in Florence, San Giovannino degli Scolopi: it was Eleonora who strongly wanted the Society of Jesus to come to Florence, with an insistence perhaps due mainly to practical reasons (“to secure Spanish-speaking confessors,” writes Lucia Meoni in the catalog, echoing Edelstein’s hypothesis).

The aim of the exhibition is to convey the idea that Eleonora was not only the “wife of Cosimo I,” but his “most important collaborator,” an ideal model of a noblewoman, a refined patroness, a careful administrator, a politician of exceptional ability, a regent of the state when the duke was absent, and a transformer of Florentine fashion. One of the most singular traits of her figure, namely her economic independence and her propensity for financial investments, which was moreover unusual in a time when women’s activities had limitations (all the more so considering that Eleonora administered her and her husband’s estates), runs more quietly, but on the whole the path devised by the curators is convincing, and the idea of Eleonora that the review wants to convey is effectively asserted both through the images of the duchess and the family, eloquent witnesses to the direction that Eleonora and Cosimo knew how to give to their government, and through the works that, Edelstein rightly writes, “continue to testify to her extraordinary role in the invention of the Medici court, which would continue to rule Florence for almost two centuries after her death.”

Finally, the good arrangement put together by Elena Pozzi, Annalisa Orsi, Giuseppe Russo and Paola Scortichini, and the voluminous catalog of more than four hundred pages, which gathers the contributions of some thirty specialists and intends to configure itself not only as a tool that condenses all the most most up-to-date on Eleanor of Toledo, but also as a starting point for new research on her figure, around which many aspects remain to be discovered, above all the first period of her life, for which we can only speculate in the total lack of documents and attestations. An exhibition of great quality to take stock of a woman to whom, thanks to her taste, culture and insights, we still owe part of the image of Florence itself in the eyes of the world.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.