by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 22/10/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition Domenico Piola 1628-1703. Pathways of Baroque Painting, in Genoa, Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino, from October 13, 2017 to January 7, 2018.

In the broad context of a national exhibition scene that often leaves something to be desired, taken as it is by following the reasons of marketing more often than those of scientific rigor, and increasingly accustomed to cutting off from the major circuits any proposal that deviates from established patterns, an exhibition such as Domenico Piola 1628-1703. Paths of Baroque Painting, underway in Genoa, seems almost an act of courage that should be rewarded regardless. Squeezed as we are between the meshes of a largely flat and homogenized system, this monograph on a painter of local scope such as Domenico Piola (Genoa, 1628 - 1703), whose production is almost entirely preserved in Liguria, is worthy of interest not only for intrinsic reasons, such as the extreme coherence of the itinerary conceived by curator Daniele Sanguineti for the venue of Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino, the punctual comparisons with the painters who suggested to Piola the “path” to take, and the relevance of the intelligent (and, if you will, also engaging) keys to interpretation provided for a vast production that is difficult to summarize with about fifty paintings (in this sense, Daniele Sanguineti has done an egregious job), but also because the exhibition on Piola is a total exhibition, involving the entire city.

In fact, the “paths” to which the title alludes unfold throughout Genoa, which is why places like Palazzo Rosso (where, in addition to the rooms frescoed by Piola, the visitor will find an exhibition of a group of about fifty of his drawings: this will be briefly accounted for in the conclusion), Palazzo Bianco, or the churches of Santissima Annunziata del Vastato, Santa Maria di Castello, and Santa Maria delle Vigne, and all the sites that the information material lists and describes precisely, are to be considered an integral part of the main itinerary, that of Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino: the historic palace on Strada Nuova, with its collected and frescoed rooms shortly before Piola was born, stands as a place more than any other suitable not only to host a review of seventeenth-century Genoese painting, but also and above all to allow the development of the curator’s interesting reflections, which seek to offer the visitor a kind of excellent guided itinerary, through the career, production and themes of Domenico Piola’s painting. And to trace this journey over half a century, Daniele Sanguineti availed himself of the ideal collaboration of Carlo Giuseppe Ratti (Savona, 1737 - Genoa, 1795), the painter and art writer who, with his Vite de’ pittori, scultori ed architetti genovesi (Lives of Genoese Painters, Sculptors and Architects ) published in 1769, augmented the work of the same name written by Raffaele Soprani a century earlier, creating a text that is still today an indispensable point of reference for the study of Genoese painting of the time: each section of the exhibition is thus introduced by quotations drawn from Ratti’s Lives. It is interesting to note that such insertions are not a mere affectation, as is usually the case in too many exhibitions: Ratti’s quotations truly constitute a guide for the visitor and are really a way of introducing him or her to the themes of the exhibition.

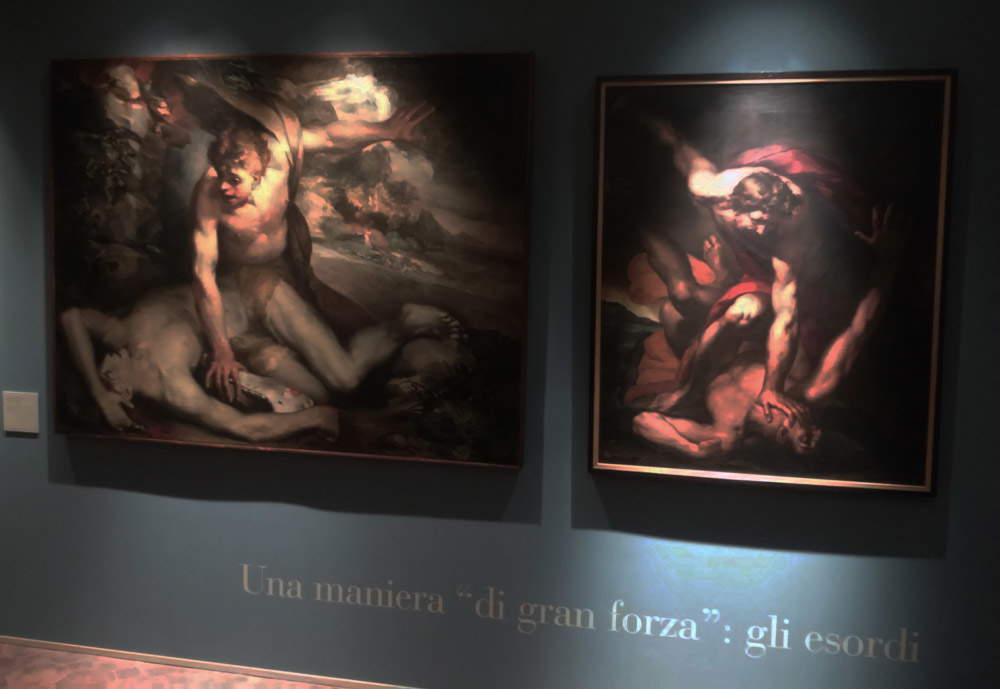

The example of the first room may help clarify. The initial section, devoted to the start of Domenico Piola’s career(Una maniera “di gran forza”: gli esordi), borrows Ratti’s definition of what we can identify as the artist’s first maniera. The Piola review can thus start from the earliest documented work known of the Ligurian artist, a Martyrdom and Glory of St. James that Domenico Piola, just 19 years old, painted in 1647 for the oratory of San Giacomo alla Marina in Genoa. “A manifesto of the intentions of a modern painter who skillfully quarries a synthesis between the most fashionable stimuli, including Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Anton van Dyck and representatives of local naturalism” (quoting from the catalog entry compiled by the curator), the painting allows us to make the acquaintance of a talented painter who, following the sketch (not in the exhibition) of Valerio Castello (Genoa, 1624 - 1659), a slightly older artist but his fundamental guide in the early years of his career, proposed a fresh and powerful work, spontaneous but founded on a “solid drawing framework.” a characteristic, the latter, that clearly distanced his painting from that of Valerius. The comparison between theenfant prodige of the Genoese Baroque and his younger collaborator comes very timely on the opposite wall: the exhibition gives us the opportunity to see three Escapes to Egypt together, all from private collections, one painted by Domenico and two by Valerio. Even to the untrained eye, the difference dividing the two artists in their early twenties will be obvious: although both share the light brushstrokes, the all-Baroque dynamism that animates the scenes and the flickers of light that enliven them, the fine Piola-like modeling possible thanks to thoughtful drawing, the more orderly and far from swirling layout and the more pronounced chiaroscuro denote an already achieved autonomy on Domenico Piola’s part. TheLast Supper in Pieve di Teco, besides being a summary of the suggestions available to Piola at the time, is also a reprise of the counterpart painting that Giulio Cesare Procaccini (Bologna, 1574 - Milan, 1625) executed in 1618 for the refectory of the Santissima Annunziata del Vastato: the comparison between the two artists, however, becomes close at the moment when we see the Cain and Abel by the Emilian painter and that of the Genoese painter side by side in the exhibition. The “great force,” precisely, with which Piola makes Cain’s head leap forward to break the two-dimensionality of the support, derives from the Procaccinesque composition, which in turn looked to models in sculpture.

|

| Domenico Piola, Martyrdom and Glory of Saint James (oil on canvas, 313 x 320 cm; Genoa, Oratory of San Giacomo alla Marina) |

|

| Comparison between Domenico Piola’s Cain and Abel (oil on canvas, 134 x 174.5 cm; Genoa, Palazzo Bianco) and that of Giulio Cesare Procaccini (oil on canvas, 122 x 99.5 cm; Turin, Pinacoteca dell’Accademia Albertina) |

|

| Domenico Piola, Last Supper (oil on canvas, 221 x 394 cm; Pieve di Teco, Museo Diocesano di Arte Sacra “Alta Valle Arroscia”) |

|

| The Flight into Egypt by Valerio Castello (center and right) and Domenico Piola (left |

The comparisons continue in the next rooms: a “tribute to the masters” presents us with a Madonna and Child by Domenico Piola, Madonna and Child with St. John by Procaccini, a Holy Family by Valerio Castello, and a painting of a similar subject by Pellegro Piola (Genoa, 1617 - 1640), Domenico’s very promising brother, murdered at the age of twenty-three, his career already launched. It is Pellegro himself who would direct Domenico toward preciousness and delicacy of Emilian matrix, notably Correggesque, which then, having passed the small section of paintings executed by Domenico in collaboration with his brother-in-law Stefano Camogli (Genoa, c. 1610 - 1690), a specialist in still lifes (in the first room, moreover, we note a radiant unpublished work by Piola and Camogli, an Abigail offering gifts to David), we punctually find in a splendid nocturne: it is anAdoration of the Shepherds that openly references Correggio’s Night, a model probably circulating in Genoa as a result of Cambiasque filtering. Set in the poor hut, theAdoration is a delightful tale that has the Child at its center, shining by his own light according to a well-established tradition, and illuminating the onlookers, all of whom participate in such a touching scene, decidedly Christmassy, to put it in modern terms. The angels in the upper register, the poses of the shepherds, and certain facial types hark back to the manner of Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, better known as il Grechetto (Genoa, 1609 - Mantua, 1664), to whom both Domenico Piola and Valerio Castello looked. Indeed: Ezia Gavazza pointed out that “to understand Valerio Castello and Domenico Piola in their outcomes without Castiglione’s medium is to deprive them of part of the cultural charge that is a fundamental element of their innovation.” More specifically, Domenico Piola spent a good deal of time copying and imitating Grechetto’s works as part of his training, and from Castiglionese cues he drew a figurative repertoire that he then declined entirely independently. The nocturne mentioned above is an example, but the visitor can also benefit from a direct comparison between an Adoration of the Shepherds by Grechetto, and Piola’s counterpart painting from Recco: just note the gestures and features of the two Madonnas.

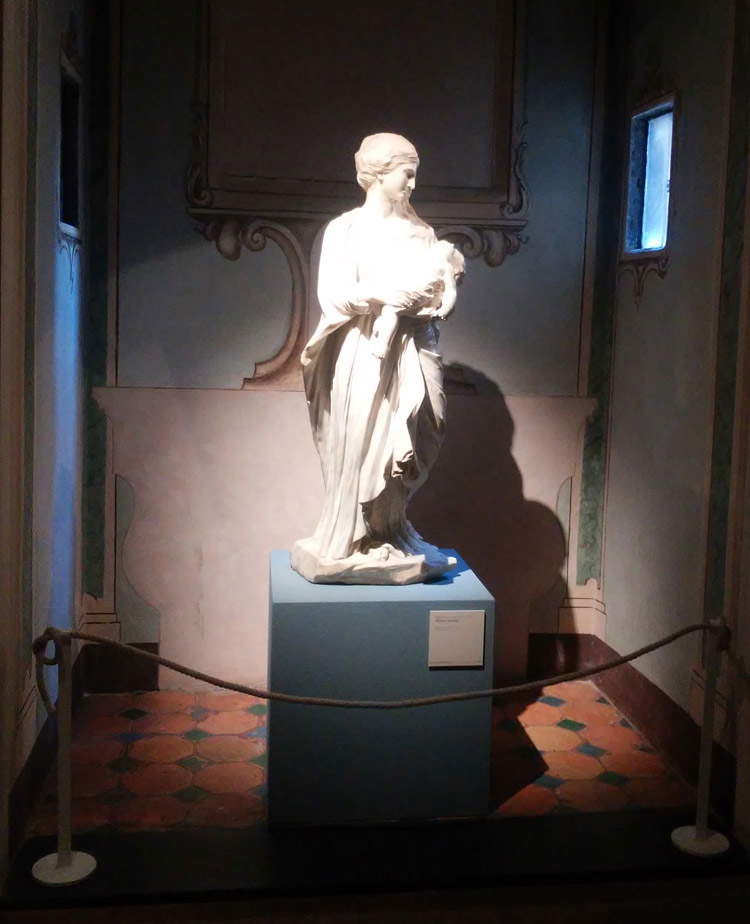

Mention was made earlier of models in sculpture, and here we need to open a parenthesis: one of the salient specifics of the exhibition are precisely the comparisons between painting and sculpture, aimed at suggesting to a certain extent to the public that idea of total art that guided the researches of many 17th-century artists. Not only that: we know, from Ratti, that Piola was a friend of two of the main sculptors active on the Genoese scene at the time, namely Filippo Parodi (Genoa, 1630 - 1702) and the Frenchman Pierre Puget (Marseille, 1620 - 1694), and he was aware of the exploits that his fellow countryman Giovan Battista Gaulli, better known as the Baciccio (Genoa, 1639 - Rome, 1709), was accomplishing in Rome together with Bernini. It is difficult to briefly summarize the ties between Piola and sculpture (a theme on which, moreover, Roberto Longhi also expressed himself): the painter was continuing in this sense a sort of Genoese “tradition,” since other greats who preceded him (Domenico Fiasella and Luca Cambiaso above all) also had relationships with sculpture. Relationships that the exhibition seeks to make explicit by exhibiting, in a specially created space taking advantage of the layout of the rooms in Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino, a marble Mother of Sorrows (but the identification of the subject is not entirely certain) by Filippo Parodi and a Project for an altar with canopy and statue of the Immaculate Madonna by Pierre Puget, by Domenico Piola: Parodi’s statue is modeled after the example of François Duquesnoy’s earlier St. Susanna in Santa Maria di Loreto in Rome (and Piola’s own production would have had points of contact with Duquesnoy’s) but also shows a certain rapprochement to the ways of Pierre Puget, whose Immaculata stands out in the center of Piola’s canopy, an element that shows how the Genoese artist made his own “the permeability and integration of the arts” (so Valentina Fiore in the catalog), moreover also drawing inspiration from the Bernini baldachin of St. Peter’s.

A comparison between sculpture and painting then returns in the exhibition’s finale: the Madonna of Mercy painted by Piola and the one carved in wood by Anton Maria Maragliano (Genoa, 1664 - 1739) are paired, facing each other. Piola’s work presents us with a Madonna clothed in white, appearing in a riot of angels and cherubs above a cloud materializing before the blessed Antonio Botta and most likely echoing Cosimo Fancelli’s idea for the marble altarpiece in the Gavotti chapel in San Nicola da Tolentino in Rome (further demonstrating how attentive Piola was to what was going on around him, and not just in painting): sculptural is the effect of three-dimensionality that Piola’s Virgin seeks to elicit, but sculptural is also the candor that seems almost to recall marble, and peculiar to a sculptor seem the draperies thus marked. Piola’s canvas thus constituted a good example for Maragliano, who, linked in friendship with the now more than 50-year-old painter (we are, it must be stressed, in the 1780s), took compositions and physiognomies from Piola.

|

| The section of the tribute to the masters with the four works compared. Left: Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Madonna and Child Jesus, St. John and Two Prophets (oil on canvas, 132 x 81.5 cm; Genoa, Palazzo Bianco). Middle: Pellegro Piola, Holy Family with St. John the Baptist (oil on canvas, 145.5 x 105.8 cm; Genoa, Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola). Right, top: Valerio Castello, Holy Family (oil on canvas, 98 x 74 cm; Private collection). Right, bottom: Domenico Piola, Madonna and Child Jesus and Little Saint John (oil on canvas, 115 x 91 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Domenico Piola, Adoration of the Shepherds (oil on canvas, 126 x 98.5 cm; Paris, Galerie Canesso) |

|

| Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione called the Grechetto, Adoration of the Shepherds (oil on copper, 65 x 56.5 cm; Palazzo Bianco) |

|

| Domenico Piola, Adoration of the Shepherds (oil on canvas, 260 x 200 cm; Recco, San Francesco) |

|

| Domenico Piola, Project for an altar with canopy and statue of the Immaculate Madonna by Pierre Puget (oil on canvas, 171 x 122 cm; Private collection, courtesy Galleria Benappi, Turin) |

|

| Filippo Parodi, Sorrowful Mother (marble, 130 x 50 x 50 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Domenico Piola, Madonna of Mercy (oil on canvas, 180 x 124 cm; Genoa, private collection) |

|

| Anton Maria Maragliano, Madonna of Merc y (carved and painted wood, 133 x 103 x 37 cm; Genoa, private collection) |

Assonances with Puget’s sculpture then recur in the two masterpieces of the section on “altar panels worked for churches and oratories,” namely St. Mary Magdalene at Prayer from the oratory of St. Mary Magdalene in Laigueglia and Our Lady of the Assumption from the church of St. John the Baptist in Chiavari, two large canvases roughly the same size (three by two meters), in which the plastic effect of the figures, especially that which distinguishes the two protagonists, owes more than a debt to Puget’s Madonnas. The two exemplars, chosen by Davide Sanguineti to give the public an account of an extremely vast sphere of Piola’s production, that of altarpieces, together with a good number of sketches placed in the same room, allow us to appreciate the characteristics of Piola’s painting in large-format pictures. Both altarpieces exhibited at Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino are works that the artist expected from 1676, are updated on a dynamism that, through the interpenetration of different scaled perspective planes, breaks the verticality of the composition, and above all aim at the direct involvement of the observer, also making use of expedients aimed at exploiting the environment that should have welcomed them. Obviously, in the exhibition it is difficult to picture the altarpieces immersed in the places for which they were conceived, but one cannot help but notice, observing for example the Magdalene of Laigueglia, how the golden light coming from the sky that spectacularly rips through the upper right corner ends up irradiating all the characters, fully investing the very refined figure of Magdalene (who does not seem in the least touched by the afflictions of her penance): the painted light, in Piola’s intentions, is meant to continue the natural light that, in the Laigueglia oratory, filters through a window.

Similarly in the ChiavariAssumption, the strongly lowered point of view (even more than in the Laigueglia altarpiece), the arrangement of the apostles all placed around the Virgin’s tomb (almost as if the central place is reserved for us who approach the scene), the gestures of the saints aimed at capturing anyone who turns their gaze to what is happening, the angels at the top who move the clouds as if they were the two halves of a curtain (a detail that increases the theatricality of the scene), are all elements that accentuate the distinctly scenographic character of the work, aiming at a first-person involvement of the observer, called to be himself the protagonist of the miraculous event to which he is witnessing, according to the typical topos of the figurative rhetoric of the Baroque age. The chiavarese altarpiece is also signed and dated 1676, with the notation appearing on the book placed in front of the tomb.

|

| Domenico Piola, Madonna Assunta (oil on canvas, 294 x 194 cm; Chiavari, San Giovanni Battista) |

|

| Domenico Piola, Saint Mary Magdalene at Prayer (oil on canvas, 300 x 198 cm; Laigueglia; Santa Maria Maddalena) |

The Genoese exhibition continually alternates between a Piola with a “public” dimension and a Piola with a “private” one, and it is worth pointing out that the seventeenth-century painter knew how to express himself with exceptional acuity even in works intended for private devotion. As soon as one leaves the “public” Magdalene of Laigueglia, the exhibition presents a marvelous St. Mary Magdalene comforted by angels intended for a private client of whom we have no information: as chaste and spiritual as the saint of Laigueglia was, so sensual and earthly is the one intended for the intimate enjoyment of her client. Certainly, Piola does not reach the carnality and eroticism of a Cagnacci or a Furini, but common to many other artists active at the time is the revisitation in a profane key of the theme of the penance of St. Mary Magdalene, rendered on this canvas as a girl with florid breasts caught in all her tangible physicality, not at all affected by the privations to which the young woman would have submitted herself according to her hagiographies. Sanguineti, in the catalog, points out literary connections between Piola’s saint and the converted sinner Mary Magdalene, the protagonist of a novel so titled and written by Anton Giulio Brignole Sale (publication dates to 1636). In the text we encounter a passage, an exclamation of the Magdalene ready to welcome divine love (yet more like the yearning of a lover than a mystical invocation), which Piola almost seems to want to transfer into image: “deh dolcezze, giubili, beatitudini: se voi forse non siete non altro che l’Amor, ond’io amo, riempitemi pure, inondatemi, submerge me pure, habbiate il mio Gesù con esso voi, perch’io ’l baci tutto, perch’io lo stringere tutto, ch’io no ’l lascierò mai più partire dalle mie braccia, acciocchéché ne meno mai più partiate.”

The visitor cannot help but notice how Domenico Piola’s manner has undergone considerable changes from that “di gran forza” of his beginnings. The guide is once again Ratti: “his figuring breathed grace, especially in the faces of the females, and of the children; and he represented the affections to the life; in which he showed how much study he had made on the natural and on the models of the Flemish [...]. The coloring then was delicate, juicy, soft, of a suave impasto, and true.” Beyond the probable reference to Duquesnoy (he could be the “Fiammingo”), this underlying sweetness that animates Piola’s second manner is to be found entirely in the private Magdalene, in her sweet and delicate face, as graceful as that of the beautiful protagonist of the Rape of Europe, which in the exhibition is displayed on the same wall, a few inches away. The painting, owned by the Carige, with its iridescence, with the soft coloring that counterbalances the sculptural plasticism of the figure of Europa, with the girl’s theatricality somehow kept at bay by the elegance of her gestures and the suavity of her body (this Europa surpasses in femininity the Magdalene flanking her), is particularly illustrative of the sweetened manners the artist arrived at in the 1960s (the Rape is probably a work from the early 1980s). The exhibition ends by giving an account of the great success achieved by the artist: a success that in the rooms of Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino takes the form of a real picture gallery, recreated as a seventeenth-century collector might have seen it in front of him. The last room thus presents us with a series of paintings made to embellish the residences of private patrons, and all with layouts designed with the place that was to receive them in mind. Choosing one or two that are more representative than others is a difficult task, not least because Piola’s production for Genoese houses was so abundant that it would tire any pen, Ratti assures us, and the selection made by Davide Sanguineti is also quite rich: all that remains is to observe live. Not least because we are inside a palace that belonged to a Genoese patrician family, in a room frescoed in the seventeenth century, with a seventeenth-century picture gallery in front of us, which painstakingly reconstructs even the taste with which paintings were arranged in a private setting at the time: ultimately, a far more immersive experience than many others officially presented as such.

|

| Domenico Piola, Saint Mary Magdalene Comforted by Angels (oil on canvas, 198 x 137 cm; Private collection, courtesy Galleria Benappi, Turin) |

|

| Domenico Piola, Rape of Europe (oil on canvas, 167 x 132 cm; Genoa, Collezioni d’arte Banca Carige) |

|

| The picture gallery in the last room |

Concerning the exhibition of drawings set up in the mezzanine of Palazzo Rosso, curated by Piero Boccardo, Margherita Priarone and Raffaella Besta, it can be said that a separate in-depth study will be needed to give an idea of the complexity of Domenico Piola’s graphic production, excellently summarized in little more than forty sheets aimed, more than at providing a complete overview (an arduous operation: there are hundreds of drawings left by Piola), at demonstrating the variety of themes addressed by the painter with the medium of drawing. For the most part, they are sketches for altarpieces or for paintings intended for domestic devotion: it should be borne in mind that Piola was for a long time the head of a flourishing workshop (remembered, moreover, with the last two paintings in Palazzo Lomellino), which operated substantially without competition. We can therefore imagine how many works came out of it, also due to the fact that Piola’satelier also worked with sculptors and carvers, to whom the artist himself supplied drawings. It will suffice here to mention two sheets that are interesting for their particularity: they are drawings for sterns of ships, of which Piola on more than one occasion found himself designing the decorative apparatus.

Leaving Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino first, and then Palazzo Rosso, and thus having completed the tour of the two exhibition venues, one can follow the booklet distributed in the exhibition to explore the Piola paths that complete the review on the great Baroque painter. To sum up in one line: first complete monographic exhibition dedicated to him, with several unpublished works of great quality, and based on an engaging model, in a sense new to Genoa (there had been no lack of synergies in the past, but never so extensive), and one that could set the standard: the current debate around exhibitions is largely about how to tie exhibitions to the territory. In Genoa, the goal was fully achieved, with an intelligent exhibition, an authentic gem to visit without hesitation to discover the production of one of the great protagonists of seventeenth-century Genoa and to understand what a useful exhibition animated by original research really is. The catalog deserves a final note, which consists of a single essay (a reconnaissance by the curator that, following the sections of the exhibition, offers a lively overview of Domenico Piola’s entire artistic career), and no less than one hundred and fifty detailed and impeccable entries of the works in the two “main” venues and the works that the visitor finds in the many “satellite venues” in the city that house paintings and frescoes by Domenico Piola.

|

| Domenico Piola, Project for the Stern of a Ship with the Arms of the Republic of Genoa (pen and ink, brush and watercolor ink, white paper, 37.4 x 29.1 cm; Genoa, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe di Palazzo Rosso) |

|

| Entrance to the Domenico Piola exhibition in Genoa |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.