It now appears as timely as ever, in my opinion, the exhibition that Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino in Genoa is dedicating to Domenico Parodi (Genoa, 1672 - 1742), a late Baroque artist (in fact, the exhibition is part of the larger Genoese project Superbarocco. The protagonists. Masterpieces in Genoa 1600 - 1750) who played a leading role precisely in the 18th-century phase of updating the palace itself. Domenico Parodi. Arcadia in the Garden, curated by Daniele Sanguineti and Laura Stagno with the technical collaboration of Valentina Borniotto, is topical because the themes ofecology, the environment, sustainability, and love and respect for nature are becoming central to the debates and the art scene in recent years, and in line with this trend we could say that the exhibition addresses these themes from a double point of view. First and foremost, thePalazzo Lomellino Association was keen to specify that it intended to contribute to raising awareness and attention to the issue ofeco-sustainability through the creation of a green setting, using natural and recyclable materials and low-consumption energy. Set-ups that have been created thanks to the collaboration with theLigustica Academy of Fine Arts and the curatorship of Guido Fiorato and that are highly immersive: in fact, the exhibition rooms on the main floor of the palace have been literally transformed into real stage sets.

The walls have been given motifs reminiscent of what Parodi accomplished in reference to nature, painted backdrops and theater wings that recall the scene of the Baroque theater; the floors have been covered with large antique carpets from Genoese mansions that recall natural elements in their motifs, to give the visitor the impression of being walking on a soft meadow while projecting him or her into an outdoor environment. Contributing to this intention is the choice of dominant colors, namely the green of nature (in the first three rooms) and the blue of the sky in the fourth and last room. The writer also fully perceived this intention to bring nature inside the building, thus eliminating the boundaries between inside and outside. Secondly, the exhibition focuses on the past, analyzing of man with nature and the expedients, frequent in the Baroque period, through which spaces of Genoese mansions were designed precisely to incorporate natural elements, such as rocks, shells, plants and flowers, giving a fundamental role to nature. In fact, many mansions possessed inner courtyards, where it was not unusual to find a nymphaeum, a very scenic construction, at the center of which was a fountain, embellished with niches, statues and especially artificial caves, within whichwater flowed.

In antiquity, nymphaea were sacred places of nymphs (hence the name), located near water springs: nymphs were in fact divine beings linked to nature, woods, trees, and closely connected to water. Baroque dwellings therefore housed these mock caves populated by myths in order to tie themselves to antiquity and to the sense of sacredness that could be found in nature. In the Baroque age, the image was meant to exalt the elements of nature, also tying in with the poetics that had been disseminated by the Colonia Ligustica of Arcadia, born in 1705 thanks to Giovanni Battista Casaregi, which provided for the exaltation of an ethical value of nature regulated by reason; in this view, the spiritual and intellectual qualities of the patron were celebrated through artistic projects in the gardens. Domenico Parodi was one of the artists who best espoused the Arcadian spirit: the interior spaces opened up to an uncultivated and genuine nature through the creation of artificial and illusionistic grottoes, caverns, and rock concretions, while in the exteriors overlapping terraces, symmetries, flowerbeds, and rows of trees interspersed with creations that were meant to inspire wonder, such as fountains, nymphaea, and sculptures of deities linked to the mythological world predominated. In the early eighteenth century, therefore, the desire of some of the city’s patricians to experiment their own Arcadia with a new conception of the villa garden spread in Genoa on this naturalistic wave, and in many cases, as an expert, such projects were entrusted to Domenico Parodi: Examples are the Durazzo palace on Via Balbi (Parodi was its family artist), the villas of Romairone and Pino Sottano; in the latter he even created the “grotesque room” and the bath of Diana, employing limestone concretions and faux stalactites, corals, shells, mirrors and deities that were meant to celebrate Giovanni Luca II Durazzo and his wife Paola Franzone. Distinctive ciphers of Parodi’s most original and most scenic “transformations” were in fact the mock grotto (such as the one he created at Palazzo Brignole Sale for Anton Julius II) and the woodland theme, to give a central role to nature populated by divine figures.

Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino also passed through the hands of Domenico Parodi when the Pallavicino family, who resided in the mansion from 1711, wanted to carry out that Arcadian update mentioned earlier: the artist, son of the famous sculptor Filippo and pupil of Domenico Piola, who was his godfather and his father’s friend, was responsible for the arrangement of the upper garden and the design of the monumental nymphaeum in the inner courtyard that still attracts visitors who catch a glimpse of it already from Strada Nuova.

The collected and delightful exhibition kicks off from that very nymphaeum that Carlo Giuseppe Ratti first mentioned in his guidebook on the artistic beauties of the city in 1766 and that he also mentioned in Parodi’s biography: “the beautiful fountain in the courtyard of the Pallavicini palace in Strada Nuova in stucco worked with two beautiful and well resented terms and a Phaeton falling into the Po with two cherubs worked in stucco with much skill that well make known his much knowledge,” he wrote in the manuscript version.

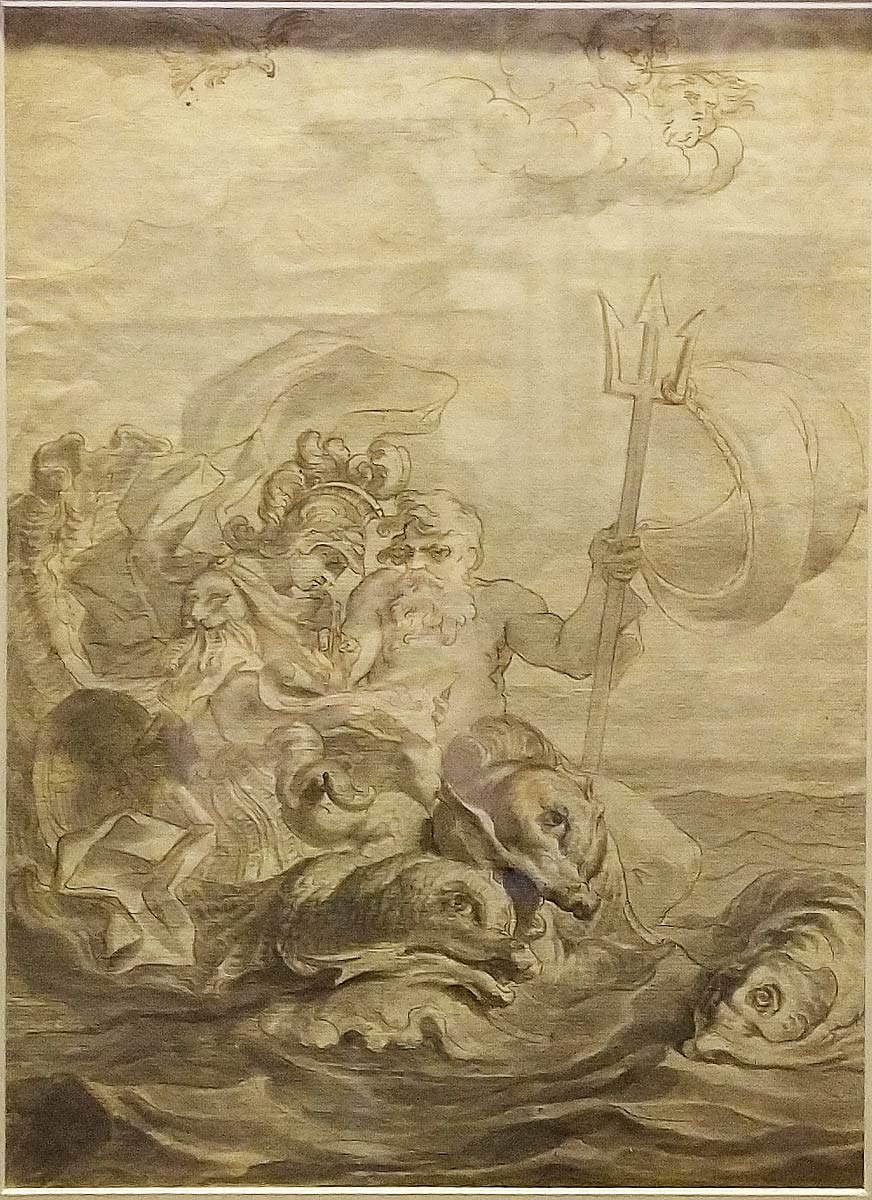

According to the testimonies, Domenico Parodi worked, renovating it, on an older pre-existing nymphaeum, to which he added the scenic practicable balcony supported by two tritons with pisciform protomes acting as telamons and delimiting a sort of naturalistic stage dedicated to the representation of the myth. However, the question of the depiction of Phaeton quoted by Ratti remains debated since it deviates from Parodi’s drawing in the exhibition coming from the Drawings and Prints Cabinet of Palazzo Rosso in which a divine river being is depicted pouring water into the mouth of the dragon below in a large shell-shaped basin. The most credible hypothesis would be that the design was modified at the behest of the patron at a stage later than the mentioned drawing: probably the fall of Phaeton was more in line with the stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses depicted on the second piano nobile. Instead, today we can admire a seated child on the highest level of the nymphaeum (perhaps personification of Eridanus), which would date from the 19th-century restorations. As for tritons, Domenico Parodi was well acquainted with the telamons made by his father Filippo for the garden portal of the Brignole Durazzo palace, even before he was familiar with Bernini’s fountain in Piazza Barberini in Rome: it was a figure widely used locally, as also evidenced by drawings in a private collection showing four pairs of tritonesses in the room with Bacchus on the second piano nobile of the Pallavicino palace.

After admiring the monumental nymphaeum by Parodi and his pupil Francesco Biggi in the inner courtyard, the tour continues to the four rooms on the piano nobile. The visitor immediately finds himself directly involved in the scenery thanks to a mirror that projects him near Paride to recall the Sala del Bagno in Pino Sottano’s Villa Durazzo. One then enters a room covered on the walls with elements of verzura taken from 18th-century prints, where designs of outdoor spaces are displayed, the design of Diana’s bath in which a nymph holds up a drape to hide a nude figure immersed in water whose legs emerge only, and designs of fountains with child Hercules choking snakes or with a putto on a shell or the one with the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus. This is followed by depictions of Diana the huntress and Adonis with a wild boar, but first and foremost to open the exhibition is theSelf-portrait from the Uffizi that Domenico Parodi sent to the Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo III de’ Medici, in which the artist portrays himself dressed as a scholar, as a personage of the culture of the time, with his turban and the damask fabric on his shoulders. He proudly displays his palette with paintbrushes, his square and compass and above all his open book as a reminder that, as a member of Arcadia, he reads the great classics such as Petrarch and the Virgilian Aeneid.

If in the second room the scenic setting features columns with caryatid figures supporting a balustrade, the third ideally leads to flowering meadows with conical trees in the center covered with colorful floral creations: the room is in fact dedicated to Spring, and representing it is Paola Maria Lomellini Adorno as Flora, the goddess of Spring. Referring to the poses of rigaudian ladies, Parodi transposes the poetics of Arcadia into the portrait, making the figure of the patron mythological: the woman advances triumphantly with fluttering veils scattering flowers from the lush bouquet she holds gathered in her robes. As Flora symbolizes fertility, the ability to generate the flowering “of all plants and green meadows still,” Paola Franzone Durazzo is also depicted with freshly picked flowers that she holds gathered in a hem of her mantle. Portrayed as a “beautiful gardener” with very pale skin and eighteenth-century hairstyle, Paola Franzone appears in the foreground over a garden view with flower beds, a pool with water features, and a nymphaeum with a statue of Adonis. The Genoese lady together with her husband Giovanni Luca II Durazzo commissioned fresco decoration with a woodland theme from Domenico Parodi in the villa of delights of Pino Sottano, and on the occasion of the couple’s wedding, the artist staged in the palace on Via Luccoli the allegory of Petrarchan poetry, an author in whom the Genoese archaeologists found inspiration.

Finally, in the last room, in which a large set design stands out, recalling the “Macchina per il divertimento di ballo” conceived by Parodi and made with the collaboration of sculptors and plasticists coordinated by Francesco Biggi for the dancing reception held in Genoa on July 23, 1716 on the occasion of the end of the Italian sojourn of the Elector of Bavaria Prince Karl Albrecht Wittelsbach, the Death of Germanicus refers to Parodi’s culture that draws history from the great Latin historians. The artist here depicts himself in the right-hand corner of the painting, closing the exhibition in the first piano nobile as the Uffizi Self-Portrait had opened it.

From the main floor one then climbs the side stairs that connect the inner courtyard where the nymphaeum is located to the upper garden, making an intermediate stop to admire seventeen papers by Italian and international architectural firms that have provided their design solution and reinterpretation of the nymphaeum. Resulting from the call The Statue and the Nymphaeum made by the Caarpa (Casana Architettura Paesaggio) studio in 2019, as part of OPEN open studios, as part of a vast project dedicated to the nymphaeum of Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino, a series of highly original and very different designs, each with its own identity, have resulted to give life to an unprecedented backdrop for the courtyard.

Upon reaching the upper garden, bordered toward the inner courtyard by a balustrade with statues of satyrs, a lush place opens up before the visitor, rich in plants, flowers and mythological suggestions; there is a pergola of fragrant wisteria, citrus plants whose orange blossoms give off an intoxicating essence, hedges that give the garden a geometric appearance punctuated in the center by a fountain with an octagonal basin. The plants present today do not correspond scientifically to Parodi’s design, but the nymphaeums with artificial grottos that can be seen at the end of the garden were made by Francesco Biggi and collaborators to Parodi’s design (with nineteenth-century interventions): one with the group of Silenus watering Bacchus surrounded by satyrs and bunches of grapes, the other with Adonis who with one knee resting on a rock is hunting a wild boar, as the myth dictates.

Thus ends, descending into the inner courtyard, the exhibition at Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino, which has the merit of having devised an exhibition itinerary closely linked to the place in which it unravels and in which parts of the structure of the palace are precisely the founding elements of the itinerary. He also had the happy intuition to deal with a very topical theme by connecting it to the way this theme was felt in the Genoese Baroque period: nature and its connection with man is therefore presented both from the point of view of the present and the ancient. The exhibition also gives an opportunity to get to know a multifaceted artist who at the same time specialized in these original projects, which enabled him to work for the most important Genoese patronage of his time, but also for an international patronage, such as the Elector Prince of Bavaria Karl Albrecht Wittelsbach, for whom he designed a series of sculptures to adorn the Marble Gallery in the Lower Belvedere.

All in all, a pleasant, unassuming exhibition that is linked to the city and brings a current theme into an exhibition project in a novel way.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.