In a present teeming with avowed travelers who cross the world from north to south, east to west (and beyond...) with such ease and mind-boggling speed that even the greatest travelers of all time would have their heads spinning, in Modena, in the new exhibition space on the ground floor of the Galleria Estense, the latter’s director herself, Martina Bagnoli, has chosen to conceive and curate an exhibition precisely on travel. Having ascertained that travel is a theme that fascinates people of all ages and tastes, because it has inherent in it the desire for escape and knowledge of other cultures, other places and other living beings, the exhibition Wonderful Adventures. Tales of Travelers of the Past (this is the title of the exhibition that can be visited until January 6, 2019 by anyone who proves curious to take a “journey” on travel), convinces for several reasons: first of all, it deals with a topic that might seem to be all too much addressed, but in fact what is presented is by no means trivial. Perhaps not everyone is familiar with characters like Jean de Mandeville or Ludovico de Varthema, or even John Baptist Ramusio or Maria Sibylla Merian. Travelers, adventurers, merchants and figures from the world of science who through books told biographical stories, historical facts, landscapes, ethnic groups and animals in a period between the 15th and 18th centuries, sometimes interweaving reality and imagination.

A considerable and characterizing aspect of the exhibition is that the books and works on display, including objects and paintings, come in most cases from the collections of the Estensi Galleries themselves and from the Biblioteca Estense Universitaria: nowadays it is almost unicuum in the panorama of Italian exhibitions to see this synergy, between the museum system and the library system of a city, aimed at the purpose of realizing a project with a definite and precise objective and construct.

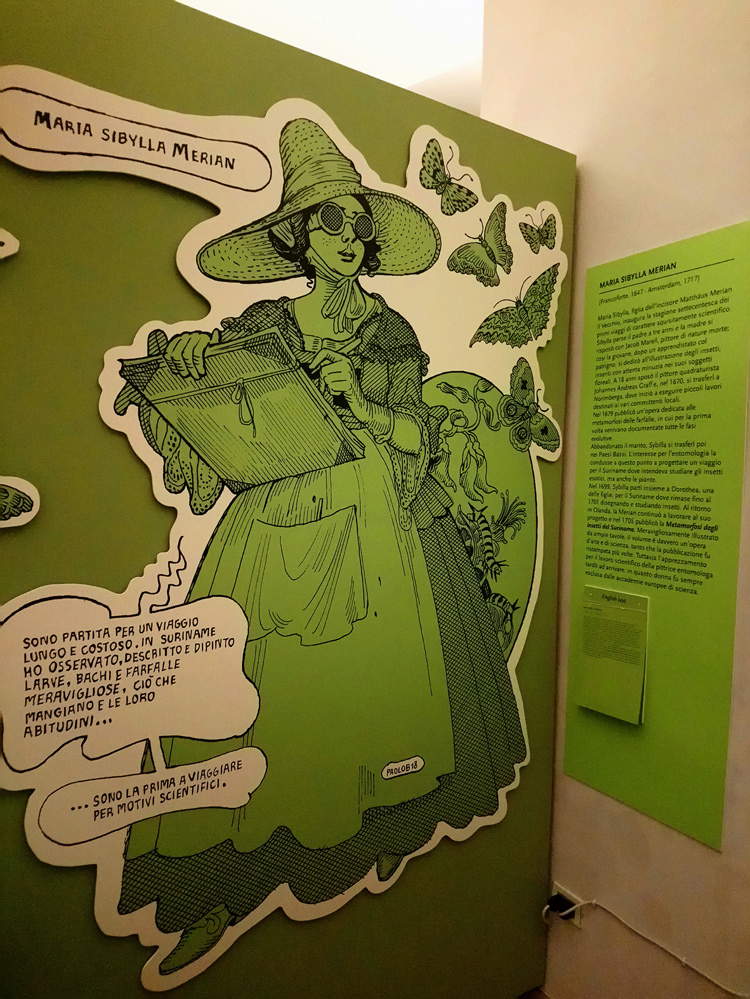

In addition to being in fact a well-researched and comprehensible exhibition, with the presence of clear display panels, its layout and thus the entire visit is particularly enjoyable: each section is colored and illustrated by the well-known cartoonist Paolo Bacilieri with life-size figures of individual travelers accompanying visitors through the exhibition.

|

| A room of the Meravigliose Avventure exhibition at the Galleria Estense in Modena |

|

| A room of the exhibition Meravigliose Avventure at the Galleria Estense in Modena |

|

| Set-ups of the Meravigliose Avventure exhibition at the Galleria Estense in Modena, Italy |

|

| Set-ups of the Meravigliose Avventure exhibition at the Galleria Estense in Modena, Italy |

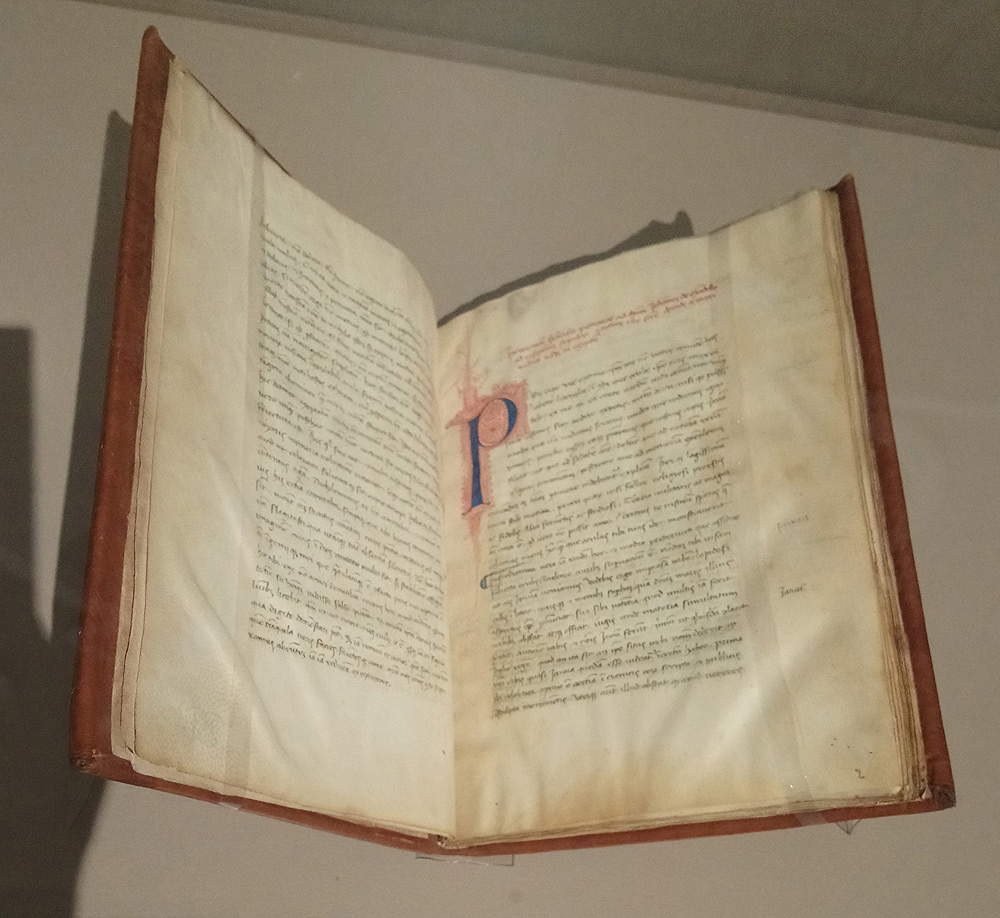

The journey begins with the Holy Land, a favorite destination since the first centuries of the Christian era for the faithful, who saw reaching this place as the pinnacle of their religious life. However, pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land had become much more numerous thanks to the establishment of the naval system between the city of Venice and Palestine: therefore, the stories of the pilgrims themselves had also increased, interweaving reality with fantasy, giving rise to a new literary genre. In this sense, pilgrimages had increasingly taken on the appearance of a journey, where everything seen as new and exotic attracted. And it is mostly unusual to discover that one of the authors of the time who had confronted such a genre was Francesco Petrarch (Arezzo, 1304 - Arquà, 1374), a celebrated 14th-century poet, best known to most for his Canzoniere. On display in the exhibition is his letter-treatise Itinerarium Francisci Petrarce ad dominum Johannem de Mandello ad visitationem sepulcri et totius Terrae Sanctae deinde a mari Rubro usque in Egyptum addressed to his young friend Giovanni da Mandello, a prominent figure in the Visconti court, who had invited him to undertake a journey together to Jerusalem. Petrarch had declined for reasons of health and fear of having to face such a long journey by sea, but he had decided to compose in just three days this letter, in which he describes on the basis of his direct experiences and his readings of classical and medieval authors the different places he would encounter starting from embarkation in Genoa.

The most extraordinary example of this genre, however, is the Book of Wonders by Jean de Mandeville, an author who is known to have written between 1343 and 1372, although his identity remains unknown to this day. The book was probably written in the 1350s and 1360s and at the time proved to be a bestseller, translated into many languages. Its success was most likely determined by the intersection in one and the same text of real facts and places with imaginary and fantastic ones, in which the influence of Pliny, Solinus, and medieval Bestiaries is captured. A book in which the author’s journey to Jerusalem is recounted, but then, having reached his destination, he had headed for the East, moved by sheer curiosity and childlike exaltation.

If in the fourteenth century the widespread destination was the Holy Land, by the second half of the fifteenth century, the focus became Constantinople, due to cultural and commercial exchanges between Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Travelers thus testified, often with illustrated books, to their wanderings to the Ottoman city, but they also included records ofAsia Minor,Egypt,Arabia and Syria. Among the most prominent figures who explored the Near East area is mentioned the Bolognese Ludovico de Varthema (Bologna, 1461/1477 - Rome, 1517): Driven by a strong desire to know personally what he had heard about, such as places, the qualities of people, the diversity of animals and the variety of plants, as well as, as he himself wrote, to “investigate some particle of this earthly globe of ours,” he had set out from Venice to disembark in Cairo and continue by sea to Lebanon and Syria. Having visited Persia, India, Siam, and the Malay archipelago, he had circumnavigated Africa. De Varthema was the first Westerner to enter Mecca, visiting the tomb of Muhammad. He recounted his long journey in his Itinerario, published in 1510, with such a strong claim to truth that it was used as a source by geographers and cartographers.

|

| Francesco Petrarch, Itinerarium Francisci Petrarce ad dominum Johannem de Mandello ad visitationem sepulcri et totius Terrae Sanctae deinde a mari Rubro usque in Egyptum (14th century; manuscript , cc. I, 48, I, 270 x 195 mm; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

![Ludovico de Varthema, Itinerario de Ludouico de Verthema Bolognese ne lo Egypto ne la Suria ne la Arabia Deserta & Felice ne la Persia ne la India & ne la Ethiopia. La sede el uiuere & costumi de tutte le presate prouincie. Nouamente impresso, pubblicato in Milano presso Giovanni Angelo Scinzenzeler (1523; XLII, [2] c., ill., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Ludovico de Varthema, Itinerario de Ludouico de Verthema Bolognese ne lo Egypto ne la Suria ne la Arabia Deserta & Felice ne la Persia ne la India & ne la Ethiopia. La sede el uiuere & costumi de tutte le presate prouincie. Nouamente impresso, pubblicato in Milano presso Giovanni Angelo Scinzenzeler (1523; XLII, [2] c., ill., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/ludovico-de-varthema-itinerario.JPG

) |

| Ludovico de Varthema, Itinerario de Ludouico de Verthema Bolognese ne lo Egypto ne la Suria ne la Arabia Deserta & Felice ne la Persia ne la India & ne la Ethiopia. La sede el uiuere & costumi de tutte le presate prouincie. Nouamente impresso, published in Milano presso Giovanni Angelo Scinzenzeler (1523; XLII, [2] c., ill., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

Other significant figures in the exhibition include Nicolas de Nicolay (La Grave, 1517 - Soissons, 1583), an official writer and cartographer to the king of France who in 1551 had accompanied the French ambassador to the court of Suleiman the Magnificent, and who produced one of the earliest collections of illustrations of the Islamic world, especially relating to customs; later, between 1693 and 1698, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri (Radicena, 1648 - Naples, 1724) had made a long journey around the world recounted in 1699 in his Around the World. In later times, in the second half of the eighteenth century, a scientific expedition had been organized through Egypt, Arabia and Syria, financed by King Frederick V of Denmark and aimed at various purposes: identifying the flora and fauna described in the Bible, making a topographical map of the Holy Land and documenting the daily life of Arabs and Jews. The mathematician and cartographer chosen for this expedition had been Carsten Niebuhr (Lüdingworth, 1733 - Meldorf, 1815), the only survivor who managed to survive the hardships and illnesses of the journey, and author of the Description of Arabia published in 1772. He had been able to reproduce inscriptions, coins, hieroglyphics and manuscripts with great accuracy.

Italian, but who became during his lifetime almost fully Chinese, so much so that the emperor knew him by the Oriental name of Li Madou, was Matteo Ricci (Macerata, 1552 - Peking, 1610). He had arrived in China by the Jesuits and had begun to study the language and carry out evangelization activities in order to spread Christianity to the educated class through the study and translation of literary classics. Ricci was considered a great astronomer: he had served at theNanjing Observatory; he was also an expert in mathematics, moral philosophy and apologetics in Chinese, but above all he had composed the first true monograph of sixteenth-century China, with his Commentaries on China and his Letters. Also significant was the contribution of Gottlieb Sigfried Bayer (Königsberg, 1694 - St. Petersburg, 1738), who intended to create a kind of dictionary andintroduction to the Chineselanguage, and Athanasius Kircher (Geisa, 1602 - Rome, 1680), a versatile man with an incredible memory, who had published China illustrata in 1667: the peculiarity of this text lies in the fact that it is not based on the author’s direct experience, but on the enormous amount of material his Jesuit brethren had provided him with on his return from the missions.

Instead, it was Giovanni Battista Ramusio (Treviso, 1485 - Padua, 1557) who was interested inIndia: in the sixteenth century for the European world India was a popular destination for spices and precious stones, which usually departed from the ports of Goa and Calicut. Names that also recur in Ramusius’ Navigationi et viaggi : a three-volume collection of travel reports by the Venetian humanist and geographer, which spread knowledge of Africa, the New World and Asia.

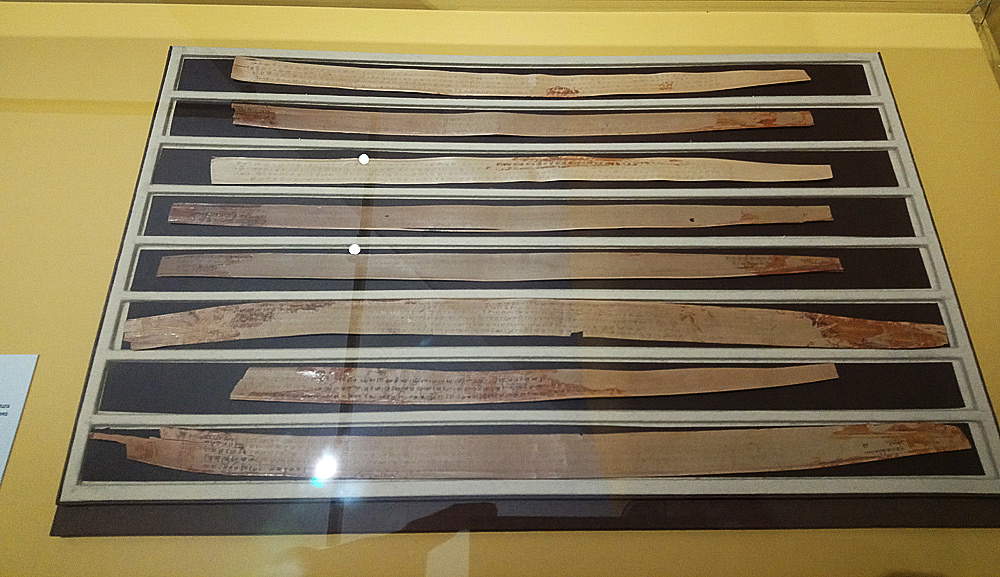

On display is a rare manuscript on palm leaves that has an inscription in the Malayalam language, an idiom spoken in India: in order for the leaves to be used as sheets of paper, they were cut, boiled in water and finally dried in the shade; the part of the central rib was removed and then they were pressed, polished and cut to size. Writing techniques differed from north to south: in the north a pen or brush was used, while in the south the leaf was engraved. A layer of charcoal powder mixed with oil was finally applied to the lettering to make the letters more visible.

![Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, Giro del mondo del dottor d. Gio. Francesco Gemelli Careri [...] Tomo primo [-nono]. - Nuova edizione accresciuta, ricorretta e divisa in nove volumi, con un indice de' viaggiatori e loro opere, pubblicato in Venezia presso Sebastiano Coleti (1728; 9 v., ill., 8°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, Giro del mondo del dottor d. Gio. Francesco Gemelli Careri [...] Tomo primo [-nono]. - Nuova edizione accresciuta, ricorretta e divisa in nove volumi, con un indice de' viaggiatori e loro opere, pubblicato in Venezia presso Sebastiano Coleti (1728; 9 v., ill., 8°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/careri-giro-del-mondo.jpg

) |

| Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, Giro del mondo del dottor d. Gio. Francesco Gemelli Careri [...] Tomo primo [-nono].- New edition enlarged, rectified and divided into nine volumes, with an index of travelers and their works, published in Venice at Sebastiano Coleti (1728; 9 v., ill., 8°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

![Carsten Niebuhr, Description de l'Arabie d'apres les observations et recherches faites dans le pays meme. Par m. Niebuhr, pubblicato in Copenaghen presso Nicolas Möller (1773; [2], XLIII, [3], 372, [2], p., XXIV c. di tav. ripieg., ill., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Carsten Niebuhr, Description de l'Arabie d'apres les observations et recherches faites dans le pays meme. Par m. Niebuhr, pubblicato in Copenaghen presso Nicolas Möller (1773; [2], XLIII, [3], 372, [2], p., XXIV c. di tav. ripieg., ill., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/carsten-niebuhr-descrizione-arabia.JPG

) |

| Carsten Niebuhr, Description de l’Arabie d’apres les observations et recherches faites dans le pays meme. Par m. Niebuhr, published in Copenhagen at Nicolas Möller (1773; [2], XLIII, [3], 372, [2], p., XXIV c. of fold-out table, ill., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

![Athanasius Kircher, Athanasii Kircheri e Soc. Jesu China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae & artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabiulium argumentis illustrata, pubblicata in Amsterdam presso Jacob van Meurs (1667; [16], 237, [11] p., [26] c. di tav. di cui [4] ripieg., ill., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Athanasius Kircher, Athanasii Kircheri e Soc. Jesu China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae & artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabiulium argumentis illustrata, pubblicata in Amsterdam presso Jacob van Meurs (1667; [16], 237, [11] p., [26] c. di tav. di cui [4] ripieg., ill., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/athanasius-kircher-cina-illustrata.JPG

) |

| Athanasius Kircher, Athanasii Kircheri and Soc. Jesu China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae & artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabiulium argumentis illustrata, published in Amsterdam at Jacob van Meurs (1667; [16], 237, [11] p., [26] c. of tables, of which [4] folded, ill., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

![Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Primo volume delle nauigationi et viaggi, pubblicato in Venezia presso eredi di Lucantonio Giunti (1550; [4], 405, [1] c., ill., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Primo volume delle nauigationi et viaggi, pubblicato in Venezia presso eredi di Lucantonio Giunti (1550; [4], 405, [1] c., ill., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/ramusio-navigatori.JPG

) |

| Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Primo volume delle nauigationi et viaggi, published in Venezia presso eredi di Lucantonio Giunti (1550; [4], 405, [1] c., ill., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

|

| Manuscripts on Palm Leaf (Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

The African world, unlike the Holy Land andArabia, had remained half-known until the seventeenth century, when evangelization had been increased mainly by Capuchins: among them was Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi da Montecuccolo (Montecuccolo, 1621 - Genoa, 1678), who had lived for a good twenty years or so in the Congo. His is the Istorica descrizione de’ tre’ regni Congo, Matamba e Angola, published posthumously in 1687, the most important and complete description of the Congo and neighboring places. Along the exhibition we learn about the work of Hiob Ludolf (Erfurt, 1624 - Frankfurt am Main, 1704): through his Historia Aethiopica, he had laid the foundations of Ethiopian studies. In a print from the illustrated work, many elephants can be seen intent on foraging for food among fallen leaves and branches on the ground, and one of the friendly, large animals is trying to shake a tree branch to drop something appetizing. In addition to Ethiopian history and culture, Ludolf had dealt with language and produced the Grammathica Aethiopica.

Olfert Dapper (Amsterdam, 1639 -1689) had devoted himself to the west coast of Africa, combining geographical and economic information in his Description de l’Afrique: in the latter he had spoken of the capital of the Benin empire as a place full of sumptuous palaces, with orderly streets, cozy and ruled by a powerful ruler; the latter consisted of a collection of buildings and courtyards surrounded by walls, and occupied an area equal to the city of Harleem. Dapper also notes that the population was not inferior to the Dutch with regard to cleanliness. In the African sphere, Pierre Sonnerat (Lyon, 1748 - 1814) had also made his contribution, who in his Voyage aux Indes Orientales had presented the appearance of a family of Hottentots, an indigenous population ofsouthern Africa, considered due to lack of knowledge as savage and beastly-looking, since they engaged in animalistic and brutal practices; however, Sonnerat had depicted them with connotations that were by no means strange.

![Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, Istorica descrizione de' tre' regni Congo, Matamba et Angola situati nell'Etiopia inferiore occidentale e delle missioni aposotliche esercitateui da religiosi Capuccini, accuratamente compilata dal P. Gio. Antonio Cauazzi da Montecuccolo [...] e nel presente stile ridotta dal P. Fortunato Alamandini da Bologna, pubblicato in Bologna presso Giacomo Monti (1687; [16], 933, [3] p., [10] c. di tav. di cui 2 ripieg., ill. e antip. calgogr., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, Istorica descrizione de' tre' regni Congo, Matamba et Angola situati nell'Etiopia inferiore occidentale e delle missioni aposotliche esercitateui da religiosi Capuccini, accuratamente compilata dal P. Gio. Antonio Cauazzi da Montecuccolo [...] e nel presente stile ridotta dal P. Fortunato Alamandini da Bologna, pubblicato in Bologna presso Giacomo Monti (1687; [16], 933, [3] p., [10] c. di tav. di cui 2 ripieg., ill. e antip. calgogr., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/giovanni-antonio-cavazzi-istorica-descrizione.JPG

) |

| Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, Istorica descrizione de’ tre’ regni Congo, Matamba et Angola situati nell’Etiopia inferiore occidentale e delle missioni aposotliche esercitateui da Religiosi Capuccini, accuratamente compilata dal P. Gio. Antonio Cauazzi da Montecuccolo [...] e nel presente stile ridotta dal P. Fortunato Alamandini da Bologna, pubblicato in Bologna presso Giacomo Monti (1687; [16], 933, [3] p., [10] c. of tables, 2 of which are folded, ill. and antip. calgogr., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

![Hiob Ludolf, Iobi Ludolf aliàs Leut-Holf dicti Historia Aethiopica, sive brevis & succincta descriptio Regni Habessinorum, quod vulgò malè Presbyteri Iohannis vocatur. In qua libri quatuor agitur [...] Cum tabula capitum, & indicibus necessariis, pubblicata in Francoforte sul Meno presso Johann David Zunner II, per i tipi di Balthasar Christoph Wust sen. (1681; [168] c., [10] c. di tav. di cui 9 ripieg., [2]c. di tav. ripieg., ill., 1 ritr. e c. geogr. calcogr., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Hiob Ludolf, Iobi Ludolf aliàs Leut-Holf dicti Historia Aethiopica, sive brevis & succincta descriptio Regni Habessinorum, quod vulgò malè Presbyteri Iohannis vocatur. In qua libri quatuor agitur [...] Cum tabula capitum, & indicibus necessariis, pubblicata in Francoforte sul Meno presso Johann David Zunner II, per i tipi di Balthasar Christoph Wust sen. (1681; [168] c., [10] c. di tav. di cui 9 ripieg., [2]c. di tav. ripieg., ill., 1 ritr. e c. geogr. calcogr., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/ludolf-aethiopica-elefanti.jpg

) |

| Hiob Ludolf, Iobi Ludolf aliàs Leut-Holf dicti Historia Aethiopica, sive brevis & succincta descriptio Regni Habessinorum, quod vulgò malè Presbyteri Iohannis vocatur. In qua libri quatuor agitur [...] Cum tabula capitum, & indicibus necessariis, published in Frankfurt am Main at Johann David Zunner II, for the types of Balthasar Christoph Wust sen. (1681; [168] c., [10] c. of tables, of which 9 fold., [2]c. of fold. tables, ill., 1 ritr. and c. geogr. calcogr., fol.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

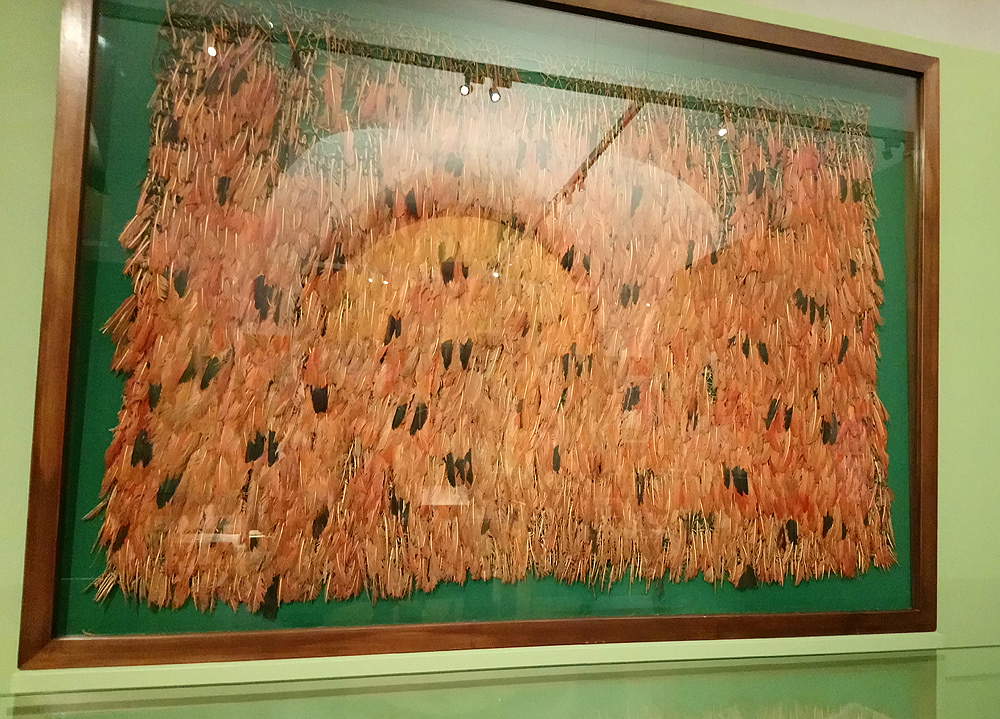

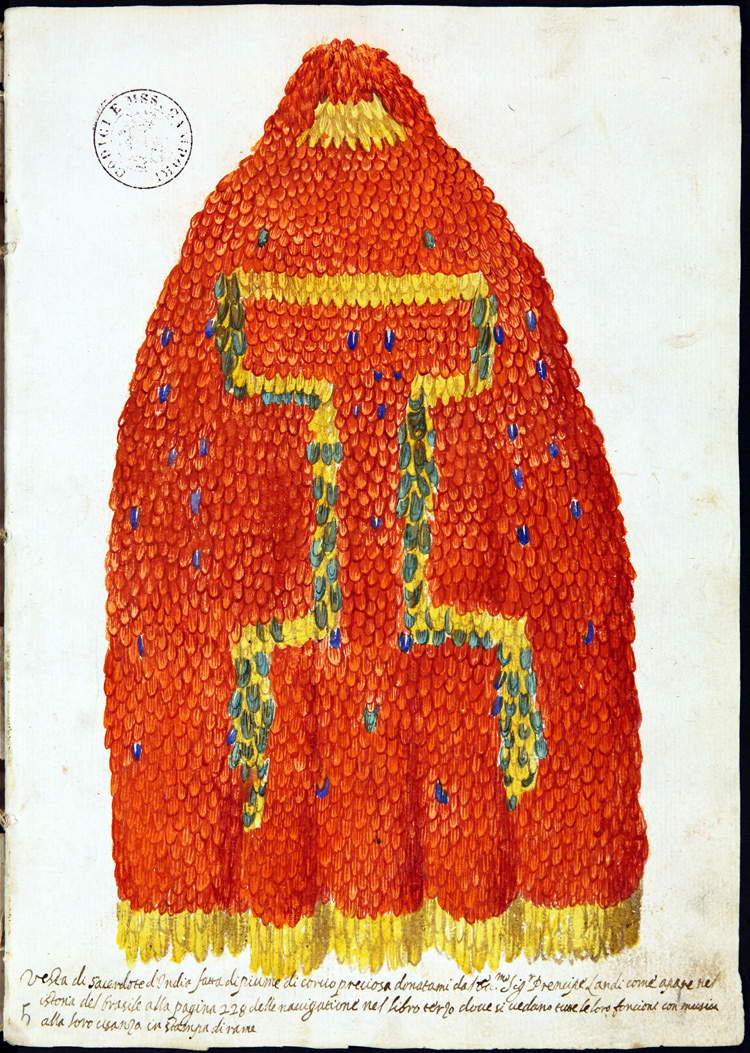

If we talk about new worlds, how can we not remember Christopher Columbus (Genoa, 1451 - Vallodolid, 1506) who had landed in San Salvador on October 12, 1492, landing in the first American land known to a European. By April 1493, Leandro de Cosco ’s Latin translation of theEpistola de insulis nuper inventis, or letter in which Christopher Columbus had described the lands he had discovered to the treasurer of the Spanish sovereigns, had begun to circulate. The narrative dwelt heavily on one aspect of those regions that had particularly impressed him: the lush vegetation with towering trees, flowers, fruits, and vast meadows. He had also been struck by the wide variety of birds that inhabited this lush nature. He had told of the natives instead as simple and generous but naked men because of their lack of culture. Columbus had learned, however, about the inhabitants ofCharis Island, who were considered very fierce: they ate human flesh and stole everything they could find. Of the peoples who practiced cannibalism, such as the Carios and the Tupinikin of Brazil, Ulrich Schmidel (Straubing, 1510 - Regensburg, 1579), who came to America in 1534 as a member of the expedition of Don Pedro de Mendoza, the first governor of the Rio de la Plata, had dealt extensively. It was Hans Staden (Homberg, c. 1525 - Wolfhagen, c. 1579) who had spread the anthropophagic rituals of this population with the account of his experience of captivity with the Tupinambas; however, the Calvinist missionary Jean de Lery (La Margelle, 1536 - L’Isle, 1613), who had lived among these natives for a year, even learning their language, had placed such rituals in war ceremonies and claimed that the Tupinambà ate their captives more for revenge than for taste. Typical of the rituals of the Tupinambà were the feathered accessories and cloaks, a specimen of which, composed of red ibis feathers, is on display in the exhibition and comes from the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Florence (in Grand Duke Cosimo II ’s inventory of 1618, two multi-colored feathered cloak-like garments up to half a leg long are mentioned). Levin Hulsius (Ghent, 1546 - Frankfurt am Main, 1606), a German writer and publisher, on the other hand had published the Breuis & admiranda descriptio Regni Guianae, written by Walter Raleigh (East Devon, c. 1552 - London, 1618), where the myth of a population of headless men, with eyes and mouth on their chests, depicted with bows and arrows, is told and illustrated: the Ewaipanoma, who, according to European beliefs, lived in a region of America.

The aforementioned Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, in his six-volume Tour of the World , shows a map depicting the Aztlan of the Aztecs, a mysterious paradise located in the northwestern part of Mexico, on Chapultepec Hill. More oriented toward theobservation and study of local flora and fauna was the voyage of Maria Sibylla Merian (Frankfurt am Main, 1647 - Amsterdam, 1717), who had undertaken a scientific expedition to Surinam in 1699 in the company of Dorothea, one of her daughters: an incredible fact for that time when one thinks of a purely scientific voyage led by a woman. The daughter of MatthäusMerian the Elder, an established Swiss engraver and draughtsman who died prematurely when Maria Sibylla was three years old, she had learned the art of drawing, painting and engraving from her stepfather Jakob Marell, a flower painter, but her real passion wasentomology and in particular the study of caterpillars and butterflies. The decision to leave for Suriname, the country of greatest prevalence of the latter, had been dictated precisely by her desire to study theorigin and reproduction of insects. Having left without funding because of the skepticism of possible supporters, she had found in the natives the fundamental help: they had shown her all the varieties of flowers, plants, insects and animals present in their land. Her Dissertatio de generatione et metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium was published six years later: the result was an extraordinary book, where the text in Latin and French was accompanied by precise and wonderful engravings. An incredible union of art and science, however, which, because it was produced by a female author, was appreciated after various times and Maria Sibylla never joined the European academies of science.

![Cristoforo Colombo, Epistola de insulis nuper inventis, pubblicata in Roma presso Stephan Plannck (dopo il 29 aprile 1493; [4] c., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Cristoforo Colombo, Epistola de insulis nuper inventis, pubblicata in Roma presso Stephan Plannck (dopo il 29 aprile 1493; [4] c., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/cristoforo-colombo-lettera.JPG

) |

| Christopher Columbus, Epistola de insulis nuper inventis, published in Rome at Stephan Plannck (after April 29, 1493; [4] c., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

|

| Original drawings that are described in the work written in Latin by Dott. Fis. Collegiate Paolo Maria Terzago, translated into Italian with augmentations by Dott. Fis. Pietro Francesco Scarabelli and printed in Voghera in 1666 in a quarto volume by Eliseo Viola (17th century; ms. cart., cc. I, 87, 310 x 225 mm; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

|

| Mantle (17th century; red ibis feathers, 125 x 70 x 8 cm; Florence, Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology) |

![Maria Sibylla Merian, Dissertatio de generatione et metamorphosibus insectorum Surinamensium: in qua, praeter vermes & erucas Surinamenses, earumque admiradam metamorphosin, plantae, flores & fructus, quibus vescuntur, & in quibus suerunt inventae, exhibentur. His adjunguntur bufones, lacerti, serpentes, araneae [...] Accedit appendix transformationum piscium in ranas, & ranarum in pisces, pubblicata all'Aia presso Pierre Gosse (1726; [10], 72 p., 72 c. di tav., ill., atl.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Maria Sibylla Merian, Dissertatio de generatione et metamorphosibus insectorum Surinamensium: in qua, praeter vermes & erucas Surinamenses, earumque admiradam metamorphosin, plantae, flores & fructus, quibus vescuntur, & in quibus suerunt inventae, exhibentur. His adjunguntur bufones, lacerti, serpentes, araneae [...] Accedit appendix transformationum piscium in ranas, & ranarum in pisces, pubblicata all'Aia presso Pierre Gosse (1726; [10], 72 p., 72 c. di tav., ill., atl.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/maria-sybilla-merian-lucertola.jpg

) |

| Maria Sibylla Merian, Dissertatio de generatione et metamorphosibus insectorum Surinamensium: in qua, praeter vermes & erucas Surinamenses, earumque admiradam metamorphosin, plantae, flores & fructus, quibus vescuntur, & in quibus suerunt inventae, exhibentur. His adjunguntur bufones, lacerti, serpentes, araneae [...] Accedit appendix transformationum piscium in ranas, & ranarum in pisces, published in The Hague at Pierre Gosse (1726; [10], 72 p., 72 c. of table, ill., atl.; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

![Ulrich Schmidel, Vera historia, admirandae cuiusdam nauigationis, quam Huldericus Schmidel, ... ab anno 1534. usque ad annum 1554. in Americam [...] iuxta Brasiliam & Rio della Plata, confecit [...] Ab ipso Schmidelio Germanice, descripta: nunc vero, emendatis & correctis vrbium, regionum & fluminum nominibus, adiecta etiam tabula geographica, figuis & alijs notationibus quibusdam in hanc formam reducta, pubblicata a Norimberga presso Levin Hulsius (1599; [2], 101, [1], p., [23] c. di tav. calcogr., ill., ritr., c. geogr., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Ulrich Schmidel, Vera historia, admirandae cuiusdam nauigationis, quam Huldericus Schmidel, ... ab anno 1534. usque ad annum 1554. in Americam [...] iuxta Brasiliam & Rio della Plata, confecit [...] Ab ipso Schmidelio Germanice, descripta: nunc vero, emendatis & correctis vrbium, regionum & fluminum nominibus, adiecta etiam tabula geographica, figuis & alijs notationibus quibusdam in hanc formam reducta, pubblicata a Norimberga presso Levin Hulsius (1599; [2], 101, [1], p., [23] c. di tav. calcogr., ill., ritr., c. geogr., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/ewaipanoma.JPG

) |

| Ulrich Schmidel, Vera historia, admirandae cuiusdam nauigationis, quam Huldericus Schmidel, ... ab anno 1534. usque ad annum 1554. in Americam [...] iuxta Brasiliam & Rio della Plata, confecit [...] Ab ipso Schmidelio Germanice, descripta: nunc vero, emendatis & correctis vrbium, regionum & fluminum nominibus, adiecta etiam tabula geographica, figuis & alijs notationibus quibusdam in hanc formam reducta, published in Nuremberg at Levin Hulsius (1599; [2], 101, [1], p., [23] c. of chalcogr. table, ill., retr., c. geogr., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

|

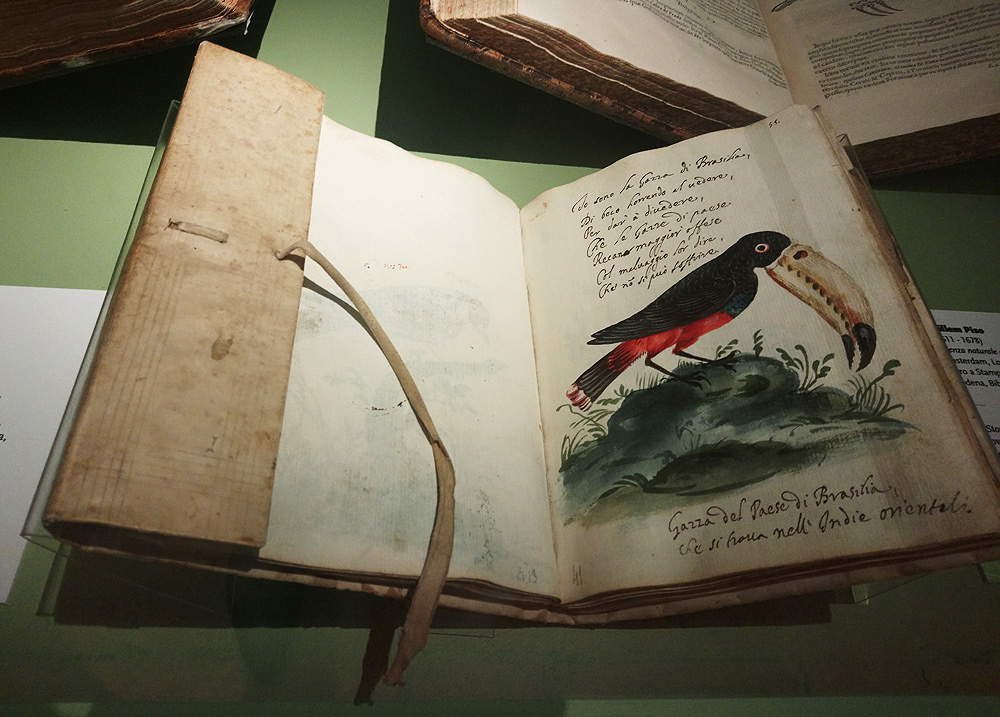

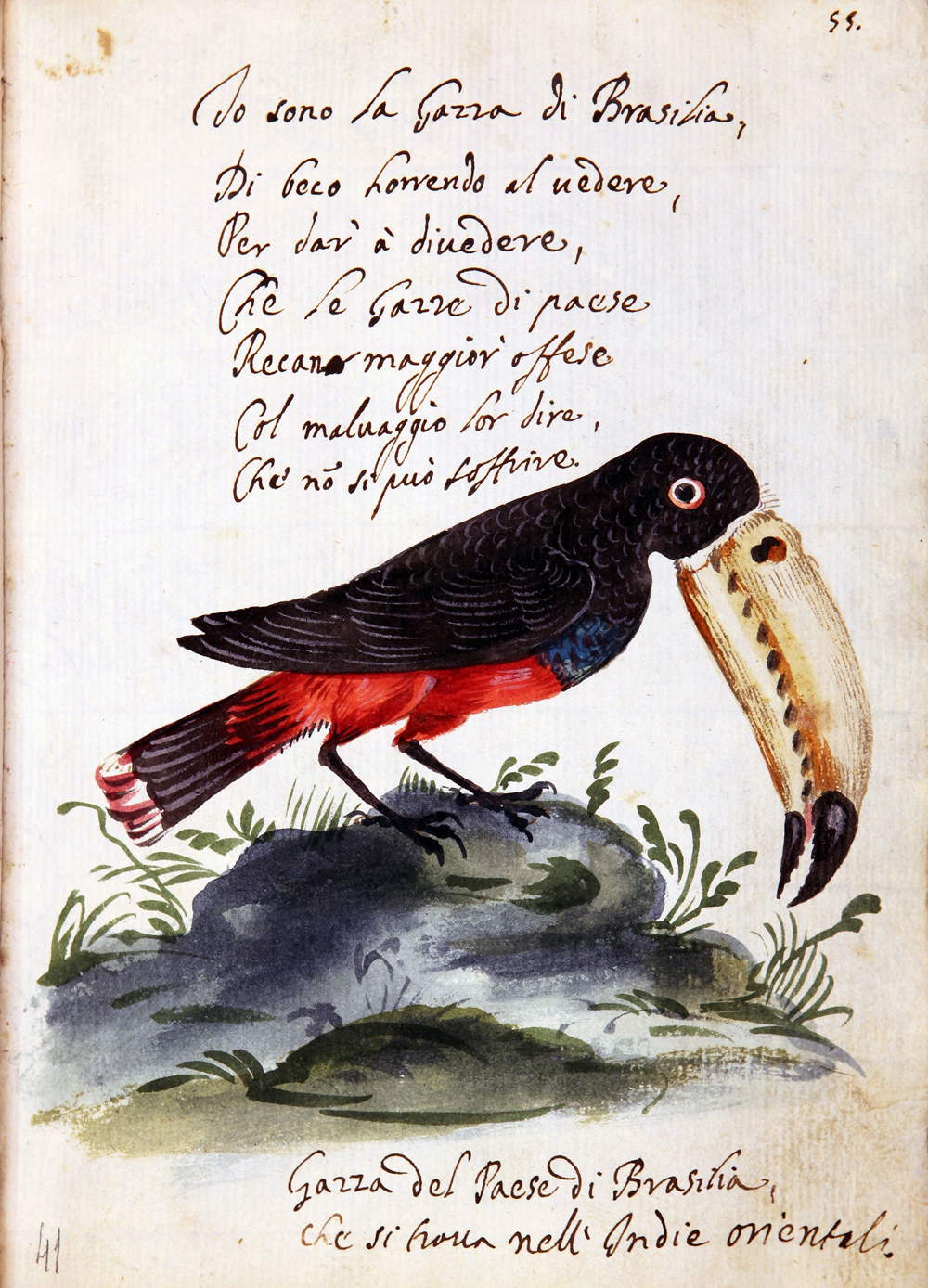

| Drawings of Animals (17th century; ms. cart., cc 102, 210 x 150 mm; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

|

| Drawings of Animals (17th century; ms. cart., cc 102, 210 x 150 mm; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

![Alonso de Ovalle, Historica relatione del Regno di Cile, e delle missioni, e ministerij che esercita in quelle la Compagnia di Giesu, pubblicato in Roma presso Francesco Cavalli (1646; [8], 378, [2], 12, 6 p., [32] c. di tav., [1] c. di tav. ripieg., ill., c. geogr., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)

Alonso de Ovalle, Historica relatione del Regno di Cile, e delle missioni, e ministerij che esercita in quelle la Compagnia di Giesu, pubblicato in Roma presso Francesco Cavalli (1646; [8], 378, [2], 12, 6 p., [32] c. di tav., [1] c. di tav. ripieg., ill., c. geogr., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2018/976/albero-crocifisso.JPG

) |

| Alonso de Ovalle, Historica relatione del Regno di Cile, e delle missioni, e ministerij che esercita in quelle la Compagnia di Giesu, published in Roma presso Francesco Cavalli (1646; [8], 378, [2], 12, 6 p., [32] c. di tav., [1] c. di tav. ripieg., ill., c. geogr., 4°; Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria) |

More popular in character, however, is the anonymous manuscript formerly owned by Modena historian Ludovico Vedriani (Modena, 1601 - 1670), consisting of 102 papers depicting animals. Among them, one on display depicts a large toucan colored black and red with a huge beak accompanied by its description, “I am the magpie of Brasilia, / of beak horrendo al vedere, / per dar à divedere, / che le gazze di paese / recan maggior offense / col malvaggio lor dire / che non si può soffrire.” Finally, another oddity noted in the exhibition is an illustration of thecrucifix-shaped tree in the forest of Limache, Chile: a curiosity recounted by Chilean Alonso de Ovalle (Santiago, Chile, 1603 - Lima, 1651) in his Historica relatione del Regno di Cile, a historical and ethnographic treatise related to the Jesuit missions published in 1646. At the end of Wonderful Adventures. Tales of Travelers of the Past one has the feeling of having traveled among the different continents presented and of having been heir to the discoveries made by great people who, out of curiosity, evangelization, desire for knowledge or scientific studies, explored lands unknown to them. One journey through books or as many “little” journeys as there are books? To the visitor his answer.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.