by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 28/06/2021

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Dante. The Vision of Art," in Forli, Musei San Domenico, through July 11, 2021.

There is a rather precise moment in the course of history when it is possible to identify the prodromes of the construction of today’s Dante myth. The Dante cult, in other words, has a place and a date of birth, namely late 18th-century England, and a surely unwitting father, Joshua Reynolds, but one who was nevertheless able to recover for the first time the themes of the Comedy without taking into account the religious, theological and moral implications of the poem, being more concerned with restoring the visionary power of Dante’s imagery. Reviving interest in Dante across the Channel had been a relief of Pierino da Vinci (thought to be by Michelangelo at the time) that had been brought to England around 1715 by the painter Henry Trench, and which had captured the attention of English cultural circles around the story of Count Ugolino della Gherardesca: and not coincidentally, the painting that Reynolds had presented in 1773 at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts was dedicated to Ugolino. For Dante scholar Lucia Battaglia Ricci, that 1773 represented a fundamental turning point in the history of Dante’s iconographic fortunes. The subsequent chapters, for that matter, are well known: the beginnings of Romanticism with Füssli and Blake bringing the themes of the Comedy back into vogue, guaranteeing the poem its success among the artists of the time, the interpretations of the Pre-Raphaelites, the Risorgimento readings of Dante’s work considered as one of the fathers of the nation, and so on.

More than an exhibition on Dante per se, the review that the San Domenico Museums in Forlì are dedicating to the Supreme Poet, or the immense Dante. The Vision of Art (a ravenous monstrosity of about three hundred works and to be visited at leisure), is an exhibition that tells the story of Dante’s fortunes over the centuries: the Forlì event therefore intervenes on a boundless subject, from which it is almost impossible to expect a complete exhibition, but this is not the key with which the exhibition must be evaluated. Dante. The Vision of Art is a grand overview that aims to offer the public an itinerary that relies on popularization and spectacular displays in order to reconstruct, in brief, the genesis of the cult of Dante, with an introduction divided into two moments (one on the Last Judgment, understood as the theological category without which it is impossible to understand the Divine Comedy, and one on the ancient illustrations of the poem, roughly from the 14th to the 16th centuries), and a narrative divided into two parts, corresponding to the two floors of the former Dominican convent: the first is centered on the figure of Dante, the second on the ways in which artists of all ages have read the three canticles of the Comedy based on their sensibilities. Detached, just before the halfway point, is an entire section devoted to printed editions between the 18th and 20th centuries, a true exhibition within the exhibition that represents the most successful and original section: a lunge that, for its display intelligence, organic character of the proposal and quality of the exhibits, alone is worth the visit.

Forlì, as is well known, is Dante’s city: in exile from Florence, Dante stopped in 1302 in the Romagnolo center that had given good reception to Guelph outcasts, and was the guest of Scarpetta Ordelaffi, the city’s Ghibelline lord (an inscription on the facade of Palazzo Albicini, built on a site where the Ordelaffi residence once stood, recalls Dante’s stay in Forlì). Dante, in 1303, leaned on Scarpetta to organize an attempt to return to Florence, which later failed at the hands of the Ordelaffi’s enemies: however, Dante would later return to Forlì on other occasions. It is a story that is marginally touched upon by the exhibition in the section devoted to civil Dante, with a painting by Pompeo Randi entitled Dante tries to persuade Scarpetta Ordelaffi to move against Florence, from a private collection in Forlì: a concession due to the city hosting the exhibition (and in any case well inserted in the context of the exhibition itinerary), and which outside of this painting does not otherwise delve into Dante’s relationship with Forlì: understandable, after all, in a review that offers little space for art contemporary or shortly after Dante, other than the personal events of the Supreme Poet.

|

| Hall of the exhibition Dante. The vision of art |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Dante. The vision of art |

|

| Danteexhibition hall. The vision of art |

|

| Danteexhibition hall. The vision of art |

|

| Pompeo Randi, Dante tries to persuade Scarpetta Ordelaffi to move against Florence (1854; oil on canvas, 140 x 176 cm; Forlì, private collection) |

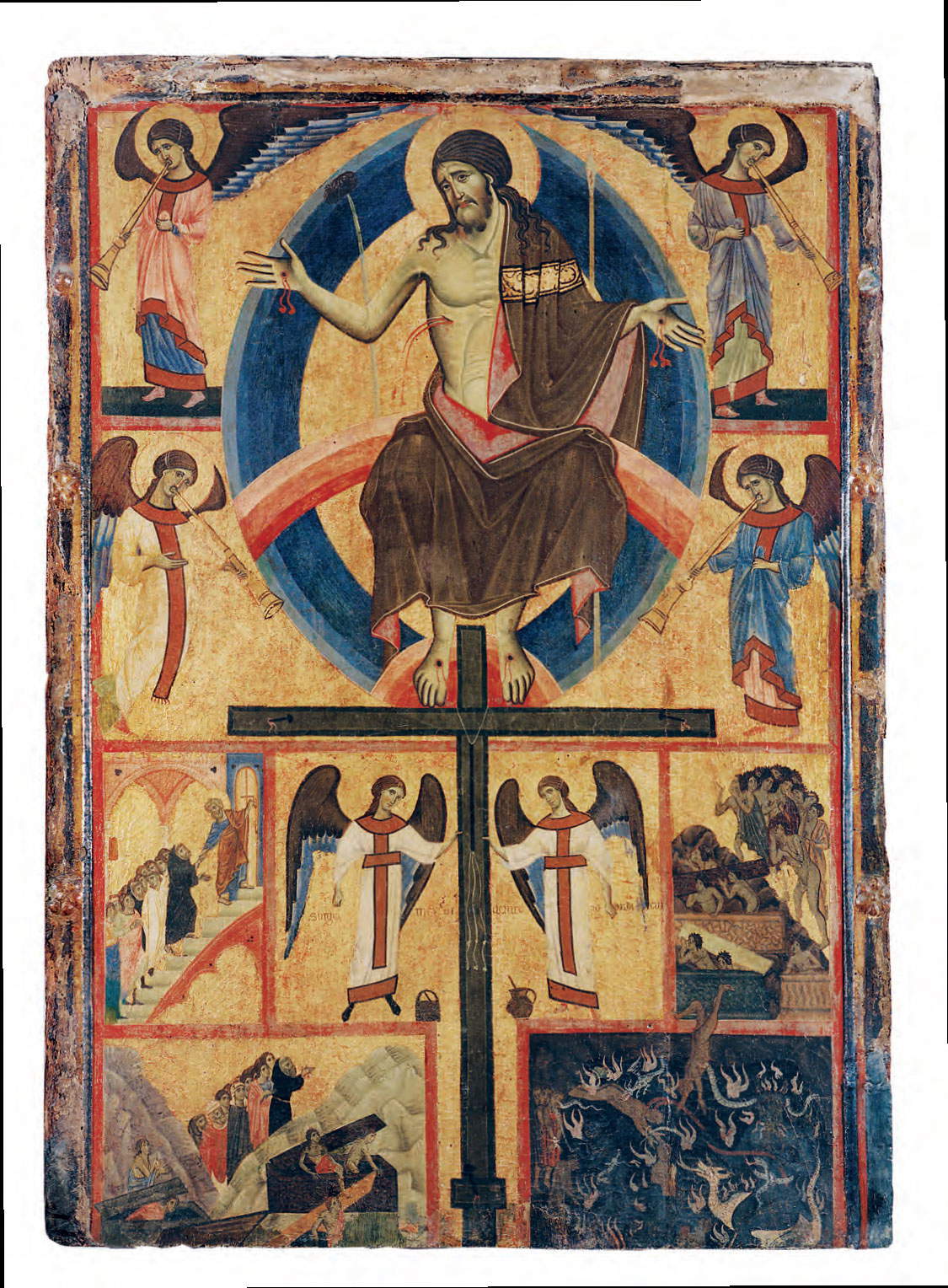

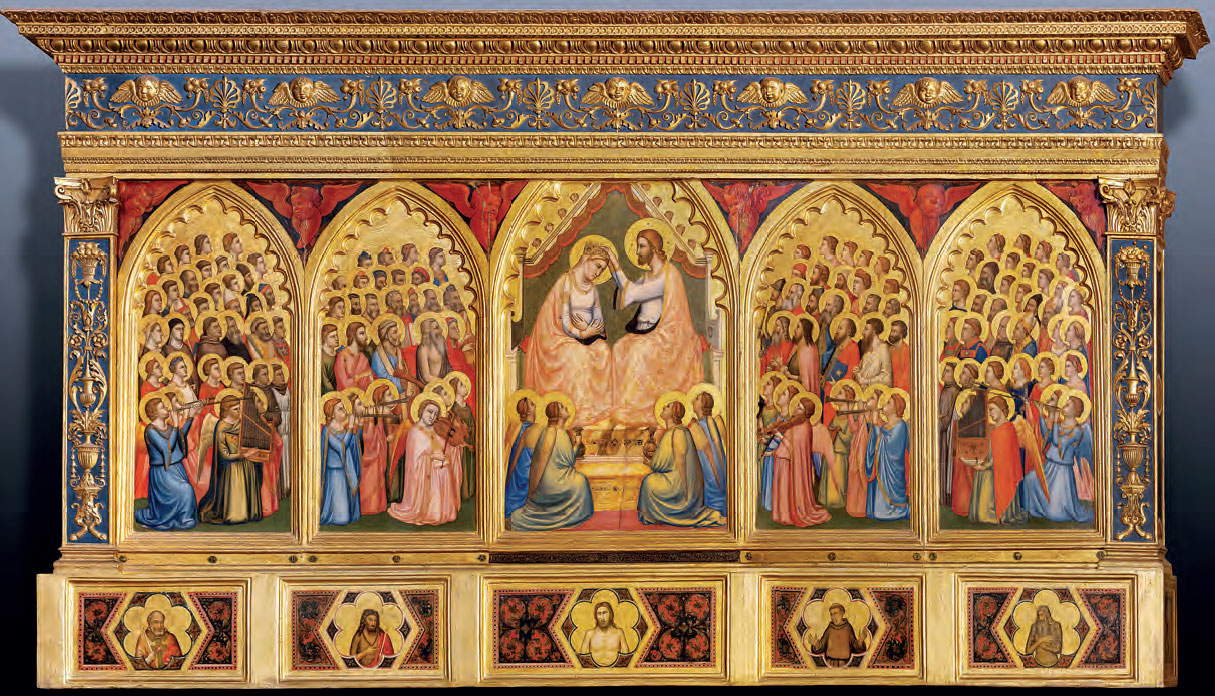

The art of Dante’s time is mostly concentrated in the first room, The Judgment and Glory, in which images of the Last Judgment from the 13th century to the late 17th century alternate. Without the concept of the Last Judgment, writes Gianfranco Brunelli (one of the four curators of the exhibition, along with Fernando Mazzocca, Antonio Paolucci and Eike D. Schmidt), “the entire poem cannot operate, because without this definitive moment there will be no eternal salvation that Dante-character seeks from the beginning of his journey to the afterlife and that Dante-narrator must recount.” A small but extremely significant nucleus of works, and preceded by a majestic Crucifix by a central-northern sculptor from the collegiate church of Santa Maria Annunziata in Poggio Mirteto, has the task of introducing the visitor to Dante’s theology: here, then, is Guido da Siena’s Last Judgment, a shining example of an iconography that Dante surely kept in mind for some of the most vivid images in his Comedy (here, an enthroned Christ, seated on the top of the cross and flanked by four angels who echo “the sound of the angelic trumpet” when “each will take up his flesh and his figure” and “will hear that which in eternity resounds.” is caught in the act of spreading out his hands to separate the elect from the damned, with the former guided to heaven by St. Peter and the others about to be hurled among the devils of hell), here is the Baroncelli Polyptych, which ranks among Giotto ’s great masterpieces to evoke the verses of the 11th canto of Purgatory in which the great Florentine artist is compared with Cimabue (“Credette Cimabue in painting tener lo campo... ”), here is also anAllegory of Redemption, circa 1338, by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, which is functional in touching on the theme of salvation, here mediated through St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans, of which the panel is a kind of translation in images, up to an early Renaissance masterpiece, Beato Angelico ’s Last Judgment, which wisely mixes Dantean cues (the Lucifer with the three mouths, for example) with authors of early Christianity (the dance of the angels, for example, which refers back to Boethius, one of the founders of Scholasticism, well known to Dante). The homage to Michelangelo cannot be missed, which can be seen as a sort of trait d’union between the introibo of the Forlì exhibition, linked to the art of Dante’s time and the artists who grappled with the theme of the Last Judgment, and the following sections: Marcello Venusti’s oil-on-canvas translation of the Sistine Chapel’s Last Judgment recalls the fundamental role the Caprese artist had in providing a figure counterpart to Dante’s imagery (“after the example of Reynolds,” Mazzocca writes in the catalog, "the privileged model for rendering the terrible grandeur of Dante’s world will continue to be identified in Michelangelo’s painting considered as a figurative counterpart to the Comedy").

There is a strong presence of the Uffizi (which alone lent about one-sixth of the works present) in the next section, devoted to the earliest illustrations of the Commedia: after the sequence of fourteenth-century manuscripts, which attest to the early fortune of Dante’s poem in Florence and its environs (a theme on which much of the exhibition on Dante at the Bargello Museum is centered) and in which the two manuscripts in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, the one attributed to Pacino da Buonaguida and the one by Niccolò di ser Sozzo (made in 1335 and before 1362, respectively), are certainly worth mentioning, the audience has the chance to linger in front of the drawings that Federico Zuccari made for his illustration of the Commedia, an undertaking to which he looked forward quite independently at the end of the century, and where for the first time images took priority over words (Zuccari’s Dante historiato contained only a selection of the poem’s tercets, “leading to a focus on Dante’s achievement of spiritual virtue in his difficult ultramontane journey,” writes Roberta Aliventi: an operation with a “moral and pedagogical intent” made explicit, moreover, by Zuccari himself in the first panel of the series, where Dante getting lost in the forest becomes a symbol of “misguided youth”). The illustrations of Dante’s works are accompanied by a series of images of the poet: above them all, stands the Dante of the series of Illustrious Men by Andrea del Castagno, exhibited in Forlì after the restoration carried out by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure.

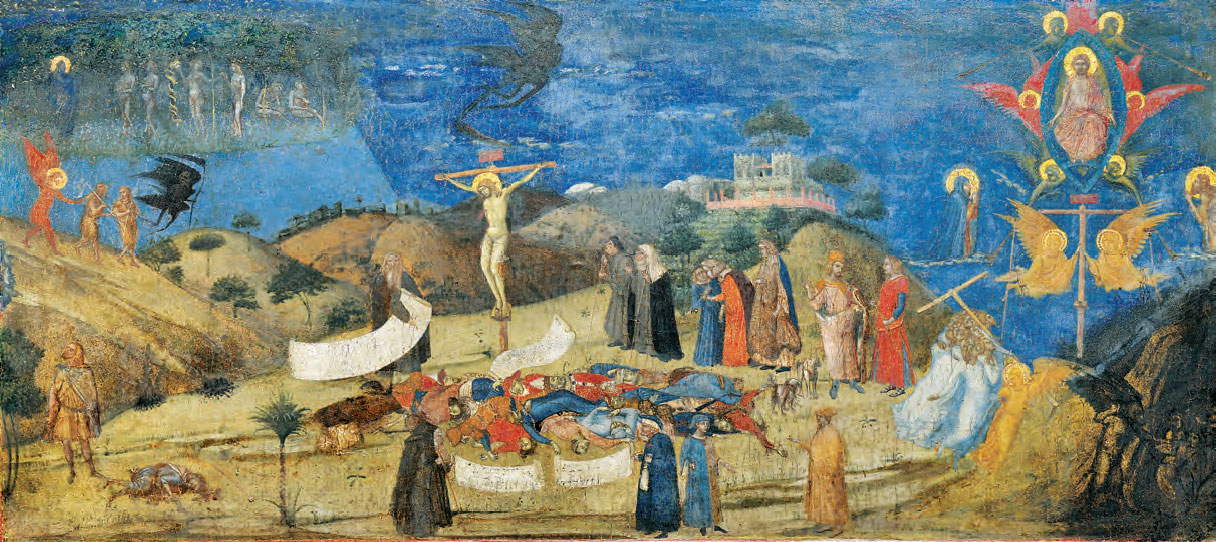

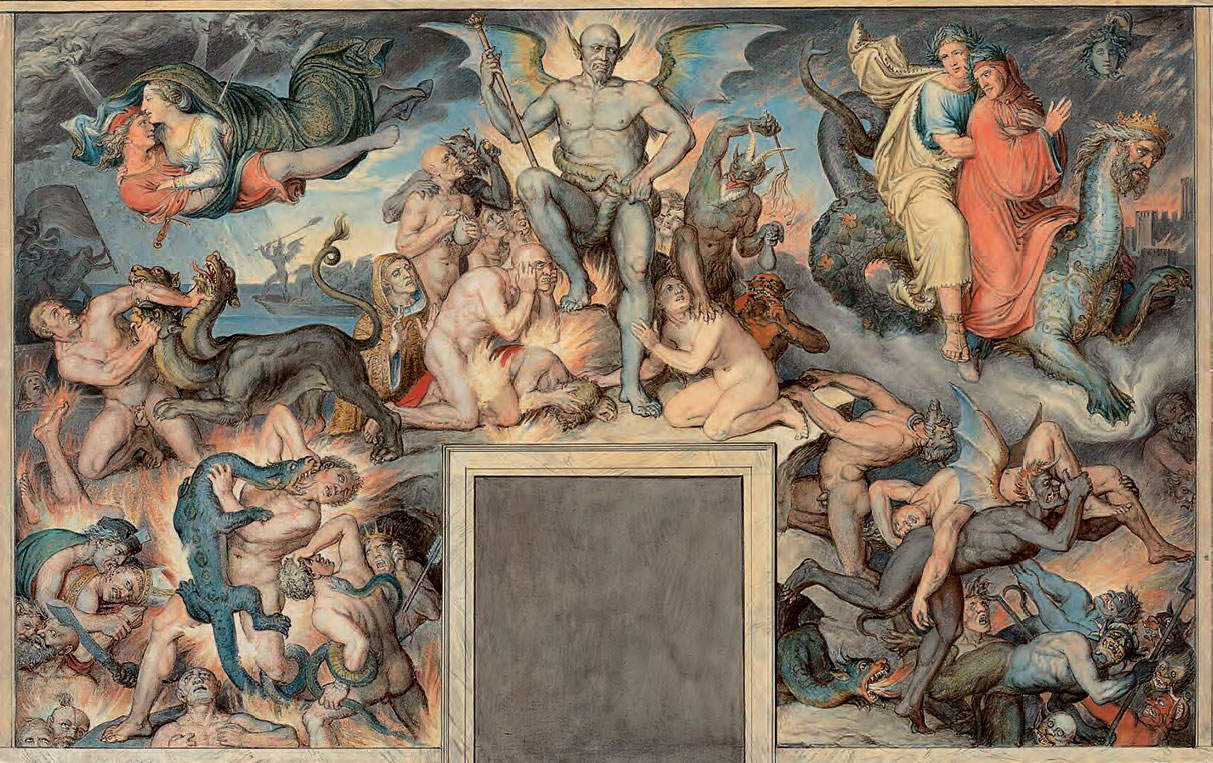

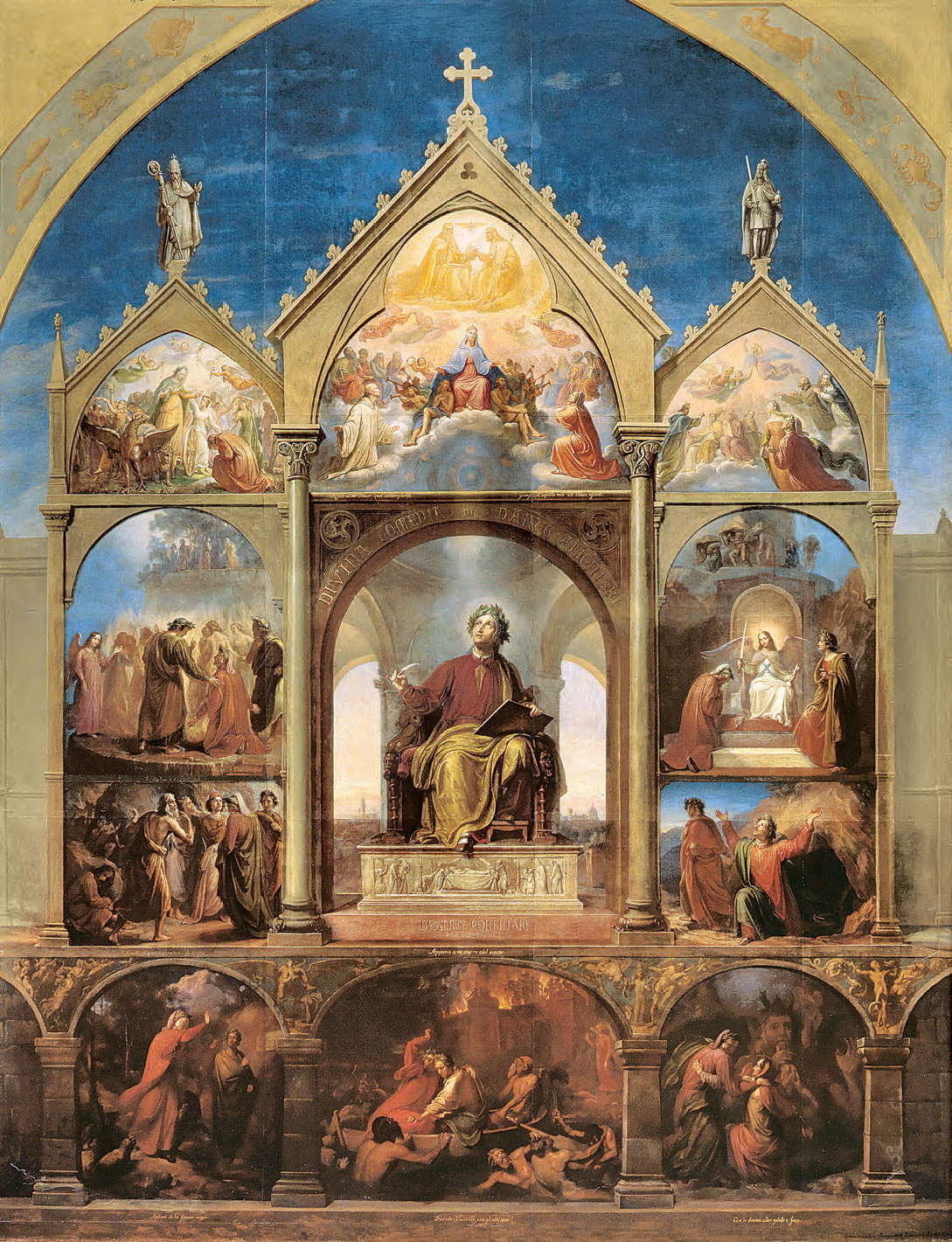

The chapter on the image of Dante connects with the first section devoted to the modern myth of Dante, the one that makes manifest the path of discovery of the Supreme Poet during the nineteenth century. One of the founding moments of the myth is the true devotion that the Nazarenes nurtured toward the Supreme Poet, above all the Tyrolean Joseph Anton Koch, who as early as 1802 manifested his intention of wanting to try his hand at illustrating the Divine Comedy: Koch did not have a chance to complete the work, stopping atInferno, but the enthusiasm he showed for Dante’s work and the echo his enterprise aroused, especially in England, played no small role in spreading the poem’s fortunes. Koch, who continued to measure himself against Dante’s works throughout his career, was attracted not only by the power of Dante’s language, but also by that “accomplished synthesis between ideal and real dimensions that the artist tries to translate graphically through a strong ’expressionism’ of feelings” (so Stefano Bosi): some of his drawings on display in the exhibition testify to his profound knowledge of Dante’s work and his ability to interpret it according to the modes of the poetics of the sublime, taking cues from Signorelli’s frescoes in Orvieto and Michelangelo’s in the Sistine Chapel (as can be guessed, moreover, from the extraordinary Inferno in watercolor, pen and pencil on loan from the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen). Picking up Koch’s legacy will be, to some extent, the younger Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein, initiated into Dante studies through his friendship with the Tyrolean: the fruit of his Dantesque meditations is an oil on paper arriving from the Uffizi, a complex and passionate painting illustrating ten episodes of the Comedy in an image that also takes on the burden of conveying to the relative the ideology that animated the poem (“Dante’s orthodoxy toward the Catholic religion , Bosi further explains, ”is reaffirmed by the cross placed on the central cusp, which in turn vindicates the unifying role of faith over spiritual and temporal power, symbolized by the statues of the pontiff and the emperor placed on the side cusps").

|

| Guido da Siena, Final Judgement (ca. 1280; tempera on panel, 141 x 99 cm; Grosseto, Museo Archeologico e dArte della Maremma - Museo dArte Sacra della Diocesi di Grosseto) |

|

| Giotto di Bondone and Taddeo Gaddi, Coronation of the Virgin among Angels and Saints (Baroncelli Polyptych) (c. 1328; tempera and gold on panel, 184 x 321 cm; Florence, basilica of Santa Croce, Baroncelli Chapel - Museo dellOpera di Santa Croce) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Allegory of the Redemption (c. 1338; tempera and gold on panel, 59.5 x 120 cm; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Beato Angelico, Last Judgment (1425-1428; tempera on panel, 105 x 210 cm; Florence, Museo di San Marco) |

|

| Federico Zuccari, Charon. Earthquake and Fainting of Dante (Inf., III) (c. 1585-1588; black and red stone on white laid paper, 448 x 615 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Andrea del Castagno, Dante Alighieri, from the cycle of Illustrious Men and Women (c. 1450; fresco detached and transported on canvas, 250 x 150 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Statue and Painting Galleries) |

|

| Joseph Anton Koch, LInferno (1825; watercolor, pen and gray and black ink over pencil traced drawing, 366 x 565 mm; Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen) |

|

| Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein, Dante and the Ten Episodes of the Divine Comedy (1842-1844; oil on paper, 2325 x 1765 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria dArte Moderna) |

This hint of a more eminently political Dante steers the public, also through a selection of works by Giuseppe Abbati that does not particularly enrich the discourse but catalyzes attention on the Italian scene, toward the section devoted to the civil cult of Dante, in a path that starts from the Risorgimento and reaches the First World War (a dense essay by Francesco Leone in the catalog is moreover devoted to this cult). The Supreme Poet’s condition as an exile is evoked by some paintings, including the one with the “Forlivian” theme mentioned in the opening (which is not only a tribute to the city but is also an exaltation of the civil Risorgimento ideals of unification through the figure of the poet), or the Dante reading the Divine Comedy at the court of Guido Novello by Andrea Pierini: the painters of the time, especially those who, like Pompeo Randi, had personally committed themselves to the cause of a united Italy, saw in Dante the first figure to have elaborated the idea of an Italian homeland, the “first vate in the civil and identity aspirations of the Italian Risorgimento, exiled and considered a Carbonaro ante litteram in the reform of the papacy,” a “symbol of liberalism and anticlericalism [....] to be exalted in medievalist pictorial reconstructions” (so Alessia Mistretta). The work that perhaps best conveys this image of a civil Dante is the Dante in exile by the Venetian Domenico Petarlini, who imagines a cogitabond and thoughtful Dante, caught in thinking about the ambasces of Italy (all the painters of the Risorgimento were well aware of the invective of the sixth canto of Purgatory: “Ahi serva Italia, di dolore ostello”). After the Unification, monuments to Dante will abound (some bronzes and sketches quickly address the theme), but the idea of seeing Dante as a symbol of national cohesion will not be diminished: this idea is conveyed by Felice Casorati’s two tempera and oil panels painted during World War I, and in which Dante’s verses comfort soldiers in irredent lands or those who fell into the hands of the enemy.</p

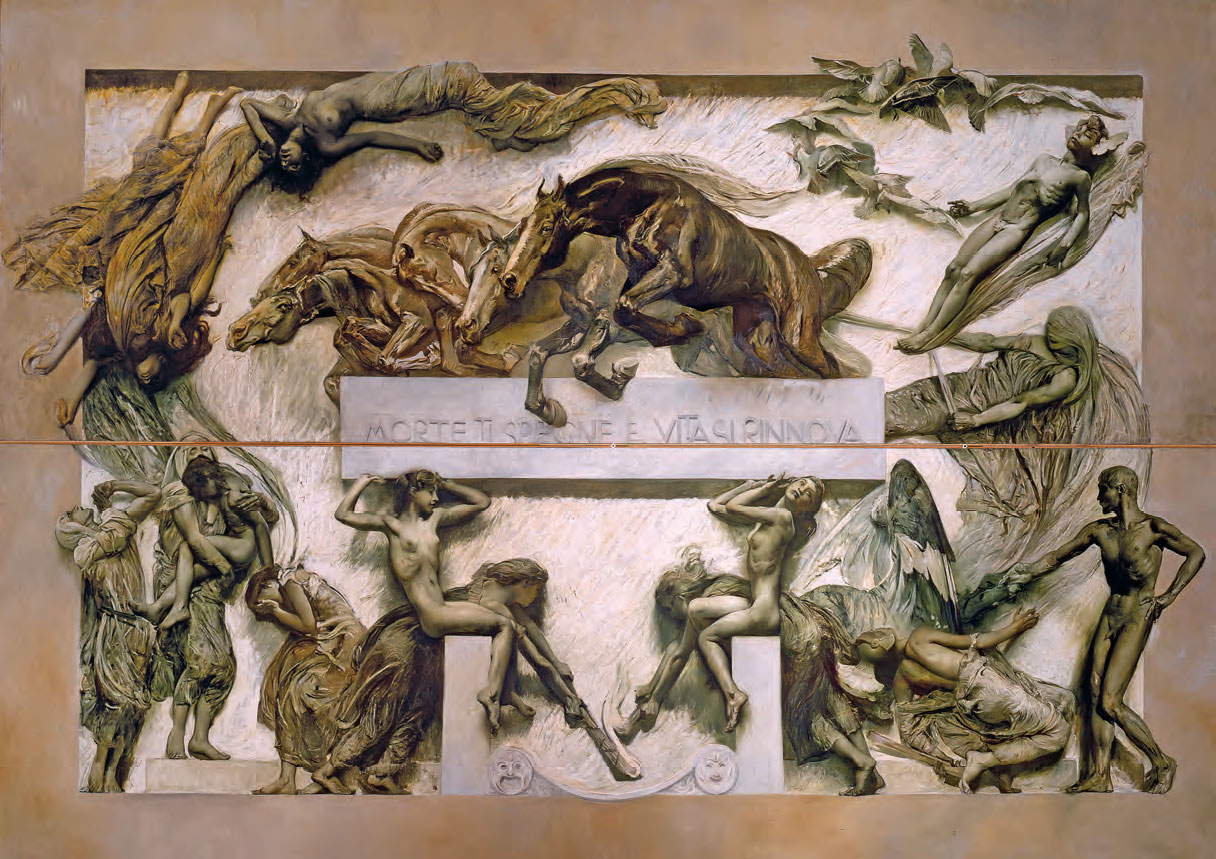

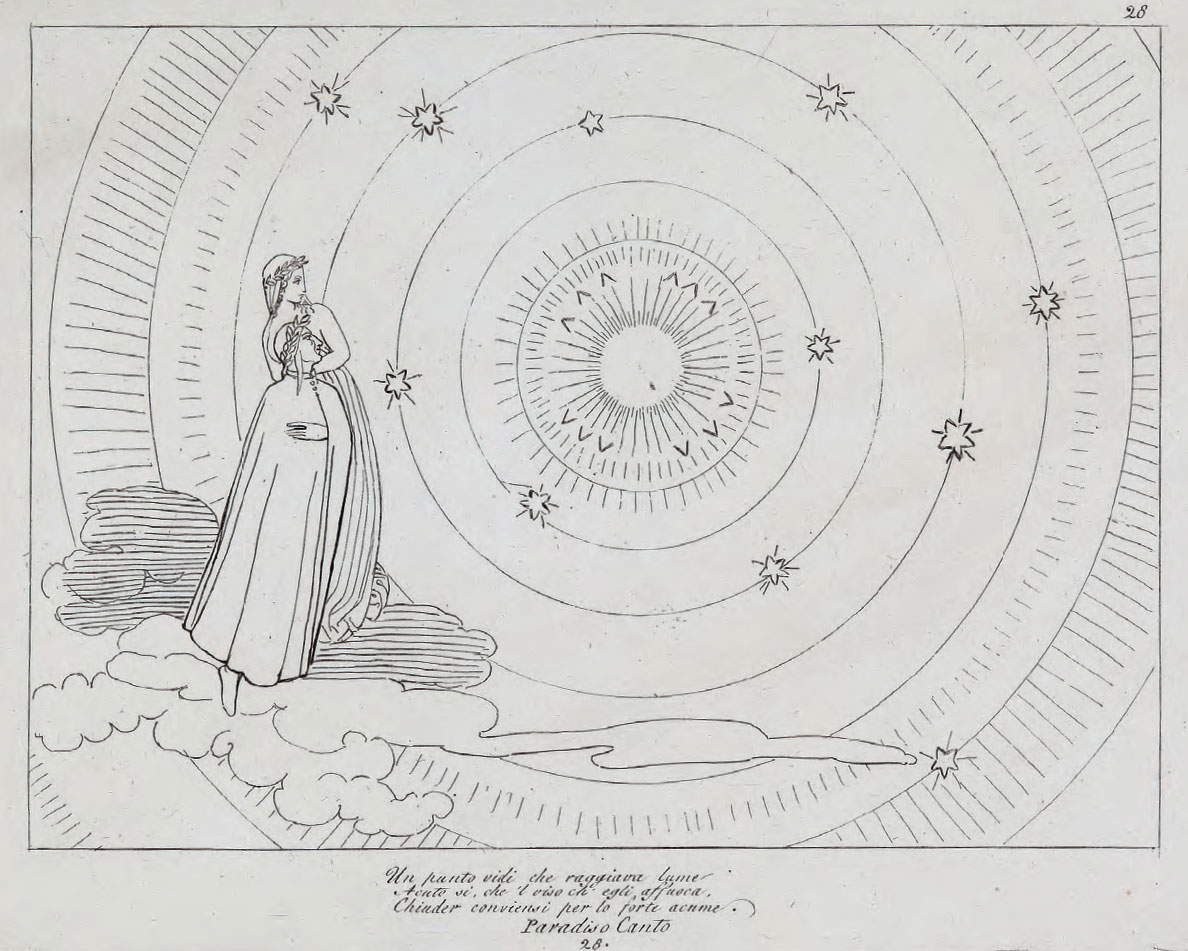

The refectory of the former convent, dominated on the back wall by Death of Giulio Aristide Sartorio, a large panel executed for the 2017 Venice Biennale, hosts the best section of the exhibition, namely, as anticipated, that on graphics. This large portion of the exhibition focuses, in particular, on the printed editions of the Commedia published between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, and in fact picks up the thread that had been interrupted in the section on illustrations between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, restarting it from 1773, the year in which, after nearly two centuries of substantial disregard for the artist (although recently the reputation of the seventeenth century as the “century without Dante” has been largely revised), publisher John Boydell in England was commissioned by Joshua Reynolds to print a mezzotint engraving, materially executed by John Dixon, of theUgolino that the English painter had presented, as mentioned in the opening, to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Reynolds and Dixon, in part through their printed translation of the painting, contributed to the spread of knowledge of Dante, popularizing the protagonists of his work: among the first to take up this interest was the great William Blake, whose plates for his illustration of the Comedy are exhibited. These are works in which, writes Francesco Parisi, who curated the section, “the artist deployed [...] some unprecedented ideas, both technical, the only line of the burin alternating with the drypoint to define the chiaroscuro transitions, overcoming the traditional rendering consisting of crossed lines enriched by dots, and conceptual, which allowed him a less allegorical reading of the poem by placing Dante’s figurations of human nature as ’stations of a path of self-reformation.’” Blake’s visionary tension is contrasted by the calmness and simplicity of the illustrations of John Flaxman, the great English neoclassical artist who also engaged in an illustration of the Comedy that is distinguished by its precise outline, a sort of trademark of the York painter, inspired by Greek vascular painting and the author of a very successful illustrated Comedy.

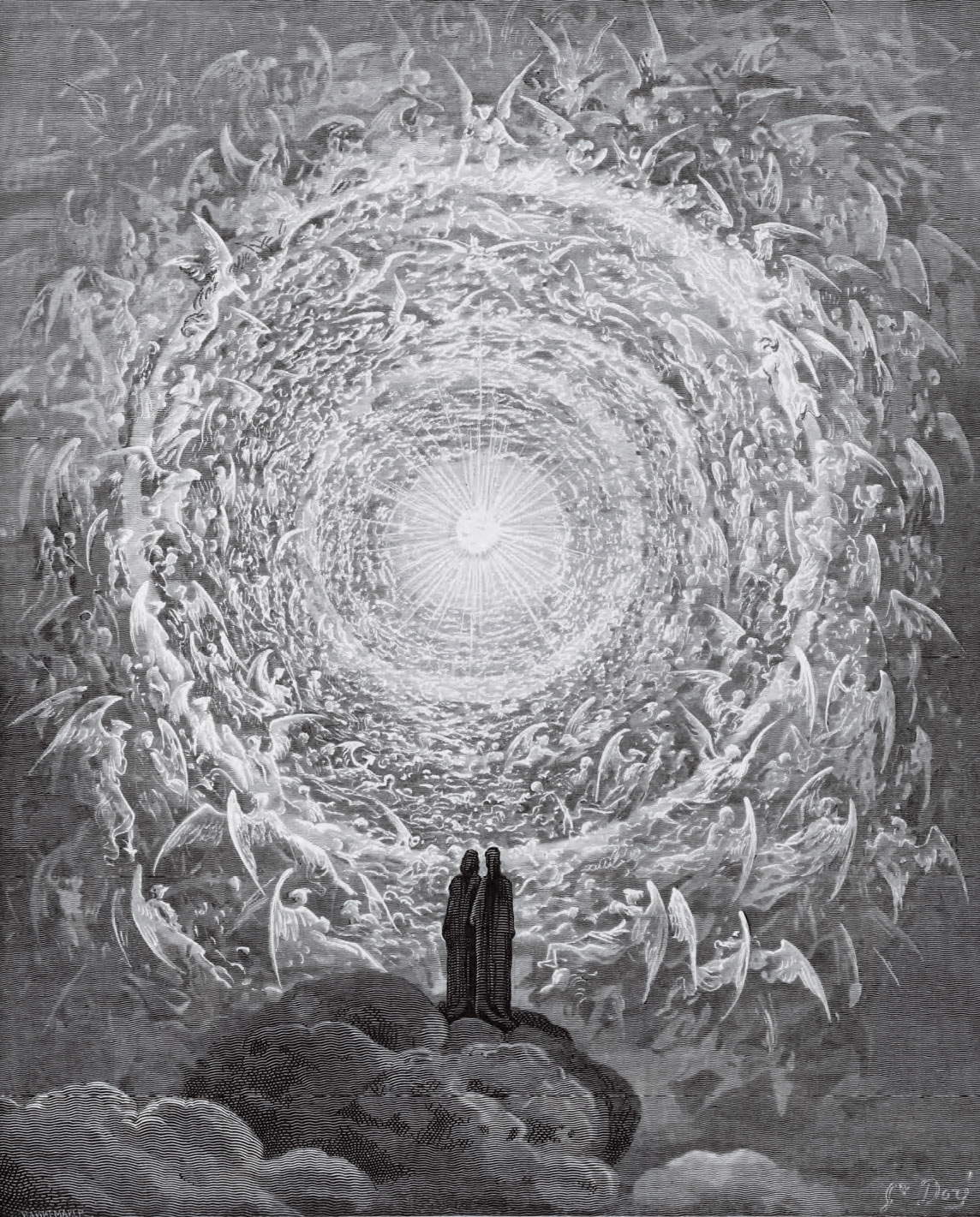

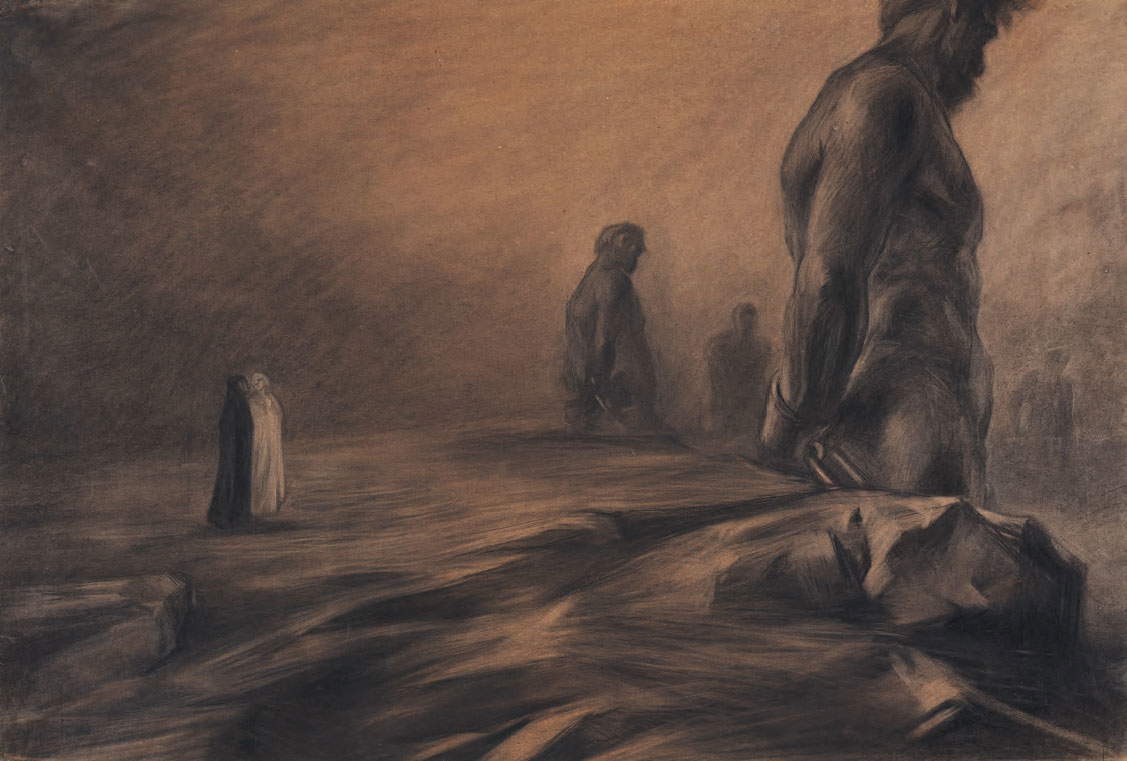

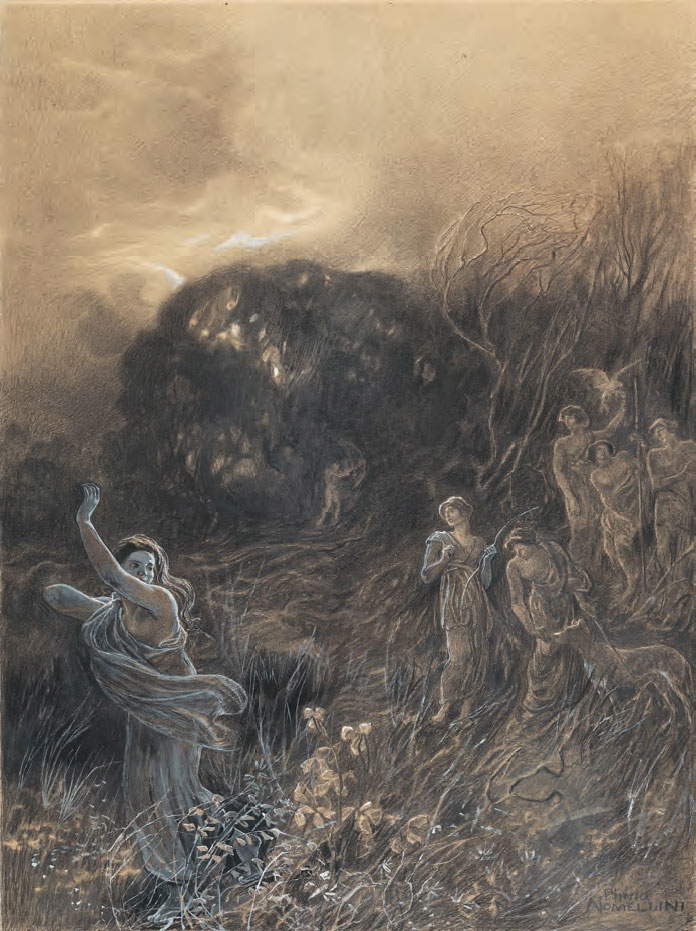

The reception on the continent of Dante’s themes is opened by a panel by the German of Italian origin Bonaventura Genelli, a friend of Koch and close to Nazarene circles, while the recovery of Dante in Italy is witnessed by the illustrations of the Florentine Luigi Sabatelli, who focused on theInferno and in particular on the scenes that most accorded with his heroic and magniloquent idea of the poem, declined according to the dictates of the eighteenth-century theory of the Sublime. On the other hand, Bartolomeo Pinelli’s engravings lie somewhere between the classical and the romantic, and along the same lines we admire a splendid drawing by Tommaso Minardi depicting the story of Count Ugolino, and then straight to the celebrated illustrations of Gustave Doré, whose first series of plates(L’enfer de Dante Alighieri avec le dessin de Gustave Doré) was given to the presses by Hachette in Paris in 1861: since other works such as Doré’s illustrations have helped to fix in the collective imagination the events of Dante’s poem. Of exceptional interest is the core of twentieth-century illustrations that the visitor encounters immediately following: from the Dante with the lily imbued with Symbolist suggestions by the versatile Leghorn artist Alfredo Müller, who imagined it for an illustration of the Vita Nova, to the surreal and monstrous fantasies of Alberto Martini, from the marvelous Nymph Helix hunted by Diana with which Plinio Nomellini participated in the competition launched in 1900 by Alinari for the illustration of the Commedia, up to the pinnacle of the illustrations of Duilio Cambellotti who, Parisi writes, “transcended the horizons of the very concept of illustration by interpreting the cantos with compositions dominated by that nocturnal and blurred atmosphere that distinguished their prduction in the first decaded el Novecento and that recalled the coeval experiences of the Roman cenacle gathered around Giacomo Balla and Giovanni Prini.”

|

| Andrea Pierini, Dante Reading the Divine Comedy at the Court of Guido Novello (1850; oil on canvas, 140 x 183 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria dArte Moderna) |

|

| Domenico Petarlini, Dante in Exile (c. 1860; oil on canvas, 76 x 96 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria dArte Moderna) |

|

| Felice Casorati, Fa come natura face in foco (Par., IV, 77) (1917; tempera on canvas, 120 x 110 cm; Private collection, courtesy Galleria Narciso, Turin) |

|

| Giulio Aristide Sartorio, Death, from the cycle The Poem of Human Life (1907; oil and cold encaustic on canvas, 513 �? 712 cm; Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Galleria Internazionale dArte Moderna di Ca Pesaro) |

|

| John Dixon (from Joshua Reynolds), Ugolino (1774; mezzotint engraving, 505 �? 625 mm; Rome, Central Institute for Graphics, Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei Deposit) |

|

| John Flaxman and Tommaso Piroli, The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri 1793 / that is / LInferno, Il Purgatorio, Il Paradiso / Composed by John Flaxman, English Sculptor, and Engraved by Tommaso Piroli Romano 1793 / In Possession of Tommaso Hope Scudiere Amsterdam / Optimo Principi Ferdinando Austr. A. D. Etrur. Mag. Duci icones delineatas ex Divina Comedia Dantis Aligherii vatis perinsignis Florentia civis D.D.D. Ioannes Flaxman (1793; album with 110 engravings, 245 x 335 x 4 cm; copy with dedication to Ferdinand III grand duke of Tuscany; Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale - by concession of the Ministry of Culture) |

|

| William Blake, The Round of the Barters, the Devils Torment Ciampolo (Inf., XXII) (1827; engravings by burin and drypoint, 240 x 340 mm each approx.; illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy Kerrison Preston Collection, Westminster Public Library) |

|

| Luigi Sabatelli, Count Ugolino with his sons in the Tower of Hunger (1794; etching on ungrained white paper, 405 x 489 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Bartolomeo Pinelli, Amor condusse noi ad una morte (1807; ink and watercolor on paper, 605 x 798 mm; Forlì, Aurelio Saffi Library, Piancastelli Fund) |

|

| Tommaso Minardi, Il conte Ugolino e lorrenda morte di lui e dei suoi figli (1843; pen, watercolor gray and sepia ink, white lead, traces of pencil on white paper, 185 x 240 mm; Forlì, Aurelio Saffi Library, Piancastelli Fund) |

|

| Gustave Doré, Le Purgatoire et le Paradis de Dante Alighieri avec les dessins de Gustave Doré, Librairie Hachette et Cie., Paris (1868; private collection) |

|

| Duilio Cambellotti, I giganti (Inf., XXXI) (1901; charcoal with white pastel highlights on paper, 553 x 808 mm; illustration for La Divina Commedia nuovamente illustrata da artisti italiani, edited by V. Alinari, Florence 1902; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, La Ninfa Elice viene cacciata da Diana, Purgatorio, Canto XXV (1900-1902; pen and color tempera on ivory paper, 800 x 600 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

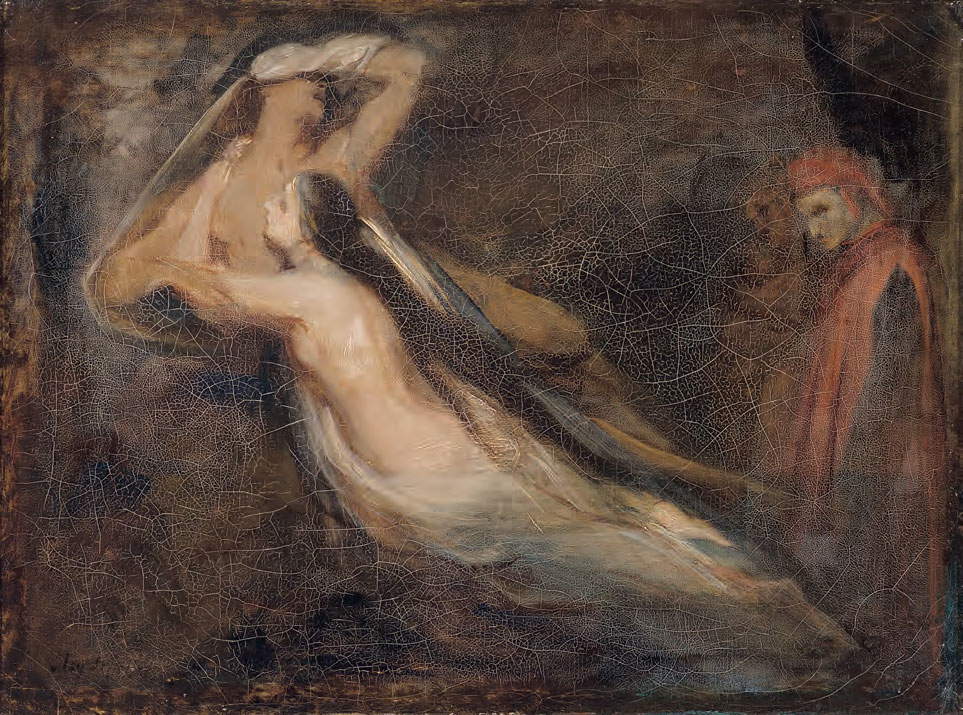

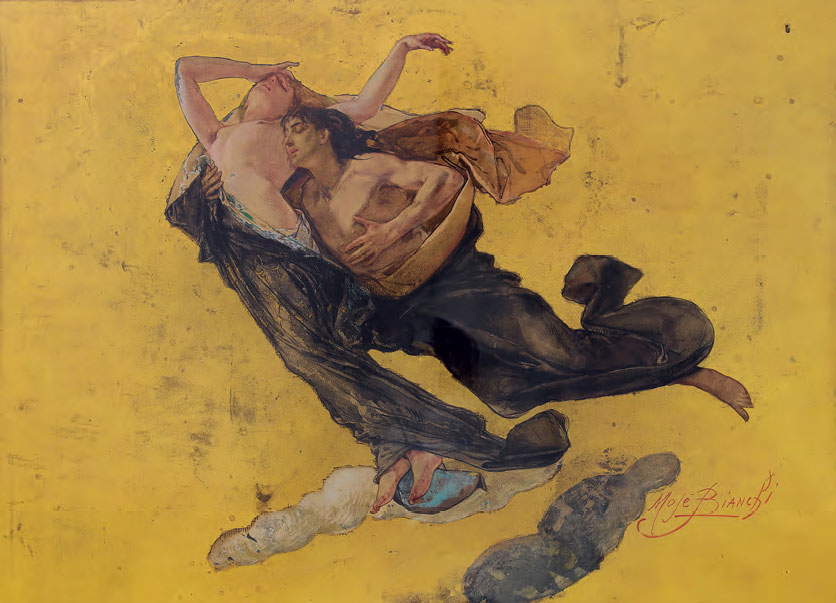

A few interluding sections in the ground-floor cells (one devoted to the “authority of the ancients” which resolves itself, rather wearily, into a string of ancient and modern busts and portraits of classical poets and philosophers, a chapter delving into the political events of Dante’s time in which Arnolfo di Cambio’s Boniface VIII and Charles of Anjou stand out, and finally a new nineteenth-century interlude on the figure of Beatrice, where the pre-Raphaelite impulses of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Henry James Holiday) alternate, lead to the staircase leading to the second floor, which is entirely reserved for the cantica of the Comedy: A journey between Hell, Purgatory and Paradise through four centuries of art. A splendid panel painting by Filippo Napoletano, arriving from the Uffizi, has the task of transporting the audience into the flames of Hades: one then enters the first of the three large rooms on the second floor, which, with an impressive choice of staging, are dark to evoke the darkness of the infernal cavity. The narration of the main episodes of the First Canticle, in the context of such a vast exhibition, can only be didactic, anthological and necessarily not exhaustive, but there is no lack of fundamental cornerstones of the iconographic fortune of the main themes of the Comedy (the events recalled by the exhibition are, as is easy to guess, those of Paolo and Francesca, Farinata degli Uberti and Ugolino). In the halls of the San Domenico Museums, the public will therefore find some must-see works, among which it is worth mentioning Ary Scheffer’s Paolo and Francesca, one of the happiest and most fortunate interpretations of the souls of the two lovers tormented by the storm, displayed next to its sculptural translation by Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, and then the neo-settecentist watercolor by Mosè Bianchi coming from the GAM in Milan, and again Gaetano Previati’s Il sogno simbolista, which transfigures the souls of two lovers in a whirlwind of absolute love, and Umberto Boccioni’s original interpretation that rereads the myth of the two lovers from Romagna to give it a personal interpretation. Then stand out, in the following rooms, a splendid marble by Carlo Fontana that captures Farinata degli Uberti in the act of rising from his tomb, the unmissable Ugolino by Giuseppe Diotti, who gave a well-known heroic reading of the story of the Pisan count, and, reaching toward the end of the infernal abyss, Franz von Stuck’s disturbing Lucifer, emblem of absolute evil.

The long corridor on the second floor is all for Purgatory: the path, as it is for Inferno, is also dotted here with paintings and sculptures that evoke Dante’s encounters, particularly the one with Pia de’ Tolomei, on which the section’s most substantial nucleus of works dwells, but no less interesting is a Guido Guinizzelli by Adolfo de Carolis (Dante meets the father of Dolce Stil Novo in Canto XXVI). Giotto’s Saint Stephen, on loan from the Horne Museum in Florence, recalls the concept of the exempla of Purgatory, the examples that are shown to souls expiating their sins as they wait to ascend to Paradise: the protomartyr saint, in particular, is shown in Canto XV as an example of meekness, for having forgiven his tormentors while being stoned to death. Dante’s encounter with Beatrice in Purgatory is recalled by Albert Maignan’s Matelda and, later, by Andrea Pierini’s canvas that depicts the poet kneeling before his beloved seated on a throne “as a Marian icon seated among angelic apparitions,” in a work “imbued with a didactic allegorism” (Sibilla Panerai). Lorenzo Lotto’sTransfiguration initiates the audience into Paradise and thus into the last two rooms of the Forli exhibition.

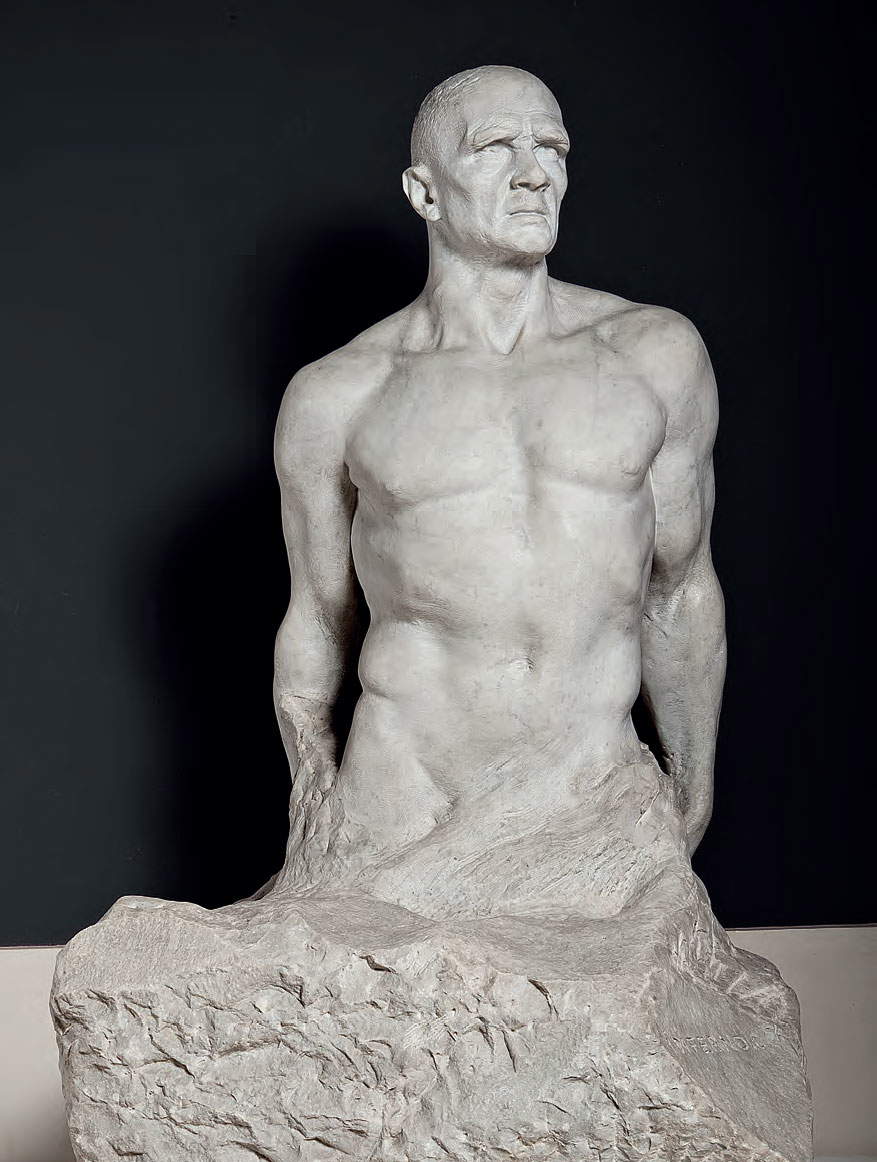

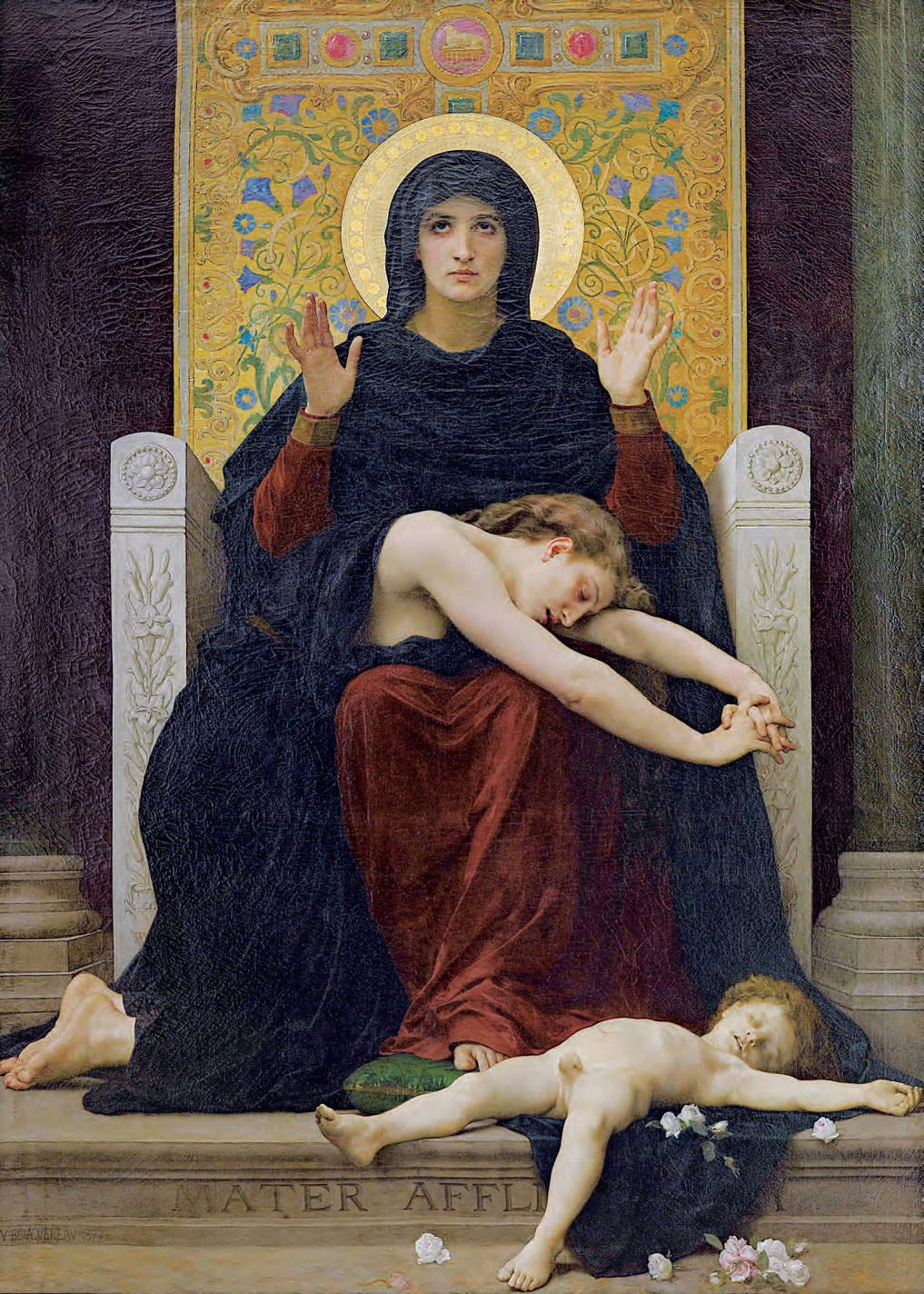

The section on Paradise, the least organic of the exhibition, is basically divided into two parts: Dante’s ascent through the heavens is retraced in the exhibition with paintings by William Dyce, Vlaho Bukovac and, further on, with Tommaso De Vivo’s Paradise, which ideally follows theInferno by the same artist exhibited in the previous rooms. In Paradise, in particular, De Vivo synthesizes the narrative from Canto XXIV to XXVII, depicting Dante kneeling before Saints Peter, James and John the Evangelist who question him on the meaning of Faith, Hope and Charity and, below them, Adam is waiting to answer the questions he reads in the Poet’s mind concerning the time elapsed since the creation of the universe (a theme, the latter, recalled moreover by two masterpieces: Antonio Canova’s Creation of the World and Previati’s Creation of Light ), that experienced by the first man in the Earthly Paradise, the reasons for original sin, and the language he spoke in the beginning. This is followed by a theory of the saints of Paradise, for which the curators have given precedence to paintings from Dante’s time (so here is Cimabue’s fundamental and very famous St. Francis arriving from the Museo della Porziuncola in Assisi, and the two tondi from the Fondazione CR Firenze by Giotto), although there is no shortage of interesting paintings by later authors such as Sandro Botticelli and Antoniazzo Romano: Guariento’s two panels arriving from the Civic Museums of Padua introduce the angelic hosts, while to give substance to St. Bernard’s prayer to the Virgin (“Virgin mother, daughter of your son / humble and high more than creature / fixed term of eternal counsel / tu se colei che lumana natura / nobilitasti sì, that her factor / did not disdain to make herself her workmanship”) the Michelangelo’s image of the Pietà for Vittoria Colonna translated into burin engraving by Giulio Bonasone and on panel by Marcello Venusti was chosen. The grand finale, in the last room, coincides with the glory and intercession of the Virgin, entrusted to Luca Signorelli’s Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Bernard, William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s Virgin Comforter, and Matteo di Giovanni’s Madonna and Child with Two Angels, and with Dante contemplating the mystery of the Trinity, recalled by Lorenzo Lotto’s powerful canvas arriving from the church of Sant’Alessandro della Croce in Bergamo.

|

| Filippo Napoletano, Dante and Virgil in Hell (1618-1620; oil on panel, 44 �? 67 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Statue and Painting Galleries) |

|

| Ary Scheffer, The Shadows of Paolo and Francesca Appear to Dante and Virgil (1835; oil on canvas, 24.5 �? 32.5 cm; Clermont-Ferrand, Musée dArt Roger Quilliot) |

|

| Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, from Ary Scheffer, Francesca da Rimini (1854; plaster, 53.3 x 67.5 cm; Colmar, Musée Bartholdi) |

|

| Moses Bianchi, Paolo e Francesca (ca. 1888; watercolor, tempera, and gold leaf on paper, 533 x 746 mm; Milan, Galleria dArte Moderna) |

|

| Gaetano Previati, Il sogno (1912; oil on canvas, 225 x 165 cm; private collection) |

|

| Umberto Boccioni, The Dream (Paolo and Francesca) (1908-1909; oil on canvas, 140 x 130 cm; private collection) |

|

| Carlo Fontana, Farinata degli Uberti (1901-1903; marble, 185 x 105 x 92 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale dArte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Giuseppe Diotti, Count Ugolino in the Tower (1831; circa oil on canvas, 173.5 x 207.5 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

|

| Franz von Stuck, Lucifer (1889-1890; oil on canvas, 161 x 152.5 cm; Sofia, National Gallery) |

|

| Adolfo De Carolis, Guido Guinizzelli (1914; sketch for the decoration of the Palazzo del Podestà, oil on canvas, 143 x 152.5 cm; Montefiore dellAso, Polo Museale San Francesco) |

|

| Giotto, Saint Stephen (1325-1330; tempera and gold on panel, 83.5 x 54 cm; Florence, Horne Museum) |

|

| Andrea Pierini, Meeting of Dante with Beatrice in Purgatory (1853; oil on canvas, 139 x 178 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria dArte Moderna) |

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Transfiguration (c. 1511; oil on panel, 302 x 212 cm; Recanati, Museo Civico Villa Colloredo Mels) |

|

| Tommaso De Vivo, Paradise (1863; oil on canvas, 161 x 240 cm; Naples, Royal Palace, on loan to the Reggia di Caserta) |

|

| Antonio Canova, The Creation of the World (c. 1820-1822; plaster, 104 x 116 cm; Possagno, Fondazione Canova onlus) |

|

| Guariento di Arpo, Angelo dei Principati (1351-1354; tempera on panel, 90 �? 58 cm; Padua, Museo dArte Medievale e Moderna) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Bernard (c. 1490-1496; painting on panel, 114 cm diameter; Fiesole, Bandini Museum, property Baduel Zamberletti Foundation) |

|

| William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Virgin Consoler (1877; oil on canvas, 204 x 148 cm; Paris, Musée dOrsay, on deposit at Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg) |

|

|

|

As part of the exhibitions organized for Dante’s 700th anniversary, Dante. The Vision of Art is a story in itself: while other museums have favored vertical reviews, the Fondazione Cassa dei Risparmi di Forlì is relaunching the model already tried and tested with the 2019 exhibition on the nineteenth century and is focusing on a horizontal and all-encompassing popularizing occasion, calibrated to the need to be appealing to a wide audience. Such a large-scale operation on Dante and the arts, facilitated by the availability of space and resources at the Foundation as well as the decisive collaboration of the Uffizi Galleries, which co-organized the exhibition, had never been attempted before, and the attempt is therefore worth a visit, without of course expecting a research exhibition: the real unprecedented (beyond the only unpublished work in the exhibition, an ideal portrait of Six Tuscan Poets from Giorgio Vasari’s workshop, and beyond the section on printed editions that features many plates that are rarely exhibited), in this case, is the sheer volume of material that the curators have been able to assemble at once. With even several masterpieces, and here we will have to ask ourselves, as always, whether it is appropriate that some works that were perhaps not so fundamental in the perspective of the exhibition’s narrative, and that are instead symbolic works of the museums of origin (such as Cimabue’s Saint Francis, or Giotto’s Saint Stephen, or even Lorenzo Lotto’s Transfiguration ), were summoned to Forlì for an exhibition where they act as comprimarios (and where they could therefore be replaced by other works without the project losing its strength). An exhibition where, in any case, all the works are useful, but few are truly indispensable.

The exhibition thus takes the form of a summary and compendium of a series of themes that are not new, but which are exposed to the public with a good popular slant and which for the first time are organized together in a broad and at times even compelling narrative, albeit with some shortcomings (the sections set up in the cells, for example: are the weakest) that can nevertheless be well understood in an exhibition that unravels along eighteen sections, or with some forcing (such as Picasso’sHarlequin brought into the exhibition to illustrate the idea of madness in Dante: there is, however, to read the card in the catalog to get an idea). The Forlì exhibition is a kind of small encyclopedia of the arts on Dante, and as an encyclopedia therefore it should be considered: a work in which there is a little bit of everything, where the opportunities for net deepening are few, but which represents the first basis for getting a broad idea about a topic. And yet, it should ultimately be emphasized that the review is well enriched by a ponderous catalog of over five hundred pages that is capable of expanding Dante ’s itinerary. The vision of art far beyond the halls in San Domenico.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.