Daniele da Volterra: d'Elci paintings on display at Corsini Gallery

It may have been the fault of the unusual warmth of a Roman evening at the end of February, or the messy traffic of people and vehicles on the Lungotevere at the end of the day, or again (and more likely) the close relevance of the assumptions that led to the birth of an exhibition such as Daniele da Volterra. D’Elci’s paintings: the fact remains that, upon leaving the splendid venue that hosts it (the National Gallery of Palazzo Corsini in Rome), our first (and lively) warm impressions of the small review were more about the form than the content, however exceptional the latter should be deemed. The point is that the exceptional nature of the event also lies in its paradigmatic guise as an operation that has arisen within a dialogue, this time a particularly fruitful one, between a public institution and a private entity. It will come as no surprise, then, that the first statement in the press release (taken from the exhibition catalog) by the director of the National Galleries of Ancient Art, Flaminia Gennari Sartori, dwells precisely on the form: “This is the first occasion during my directorship in which the Barberini Corsini Galleries host paintings from a private collection: I believe that the dialogue between the museum and the collecting universe can trigger a virtuous circle of knowledge, discovery and public sharing of our artistic heritage, and it is a path that the Galleries will continue in the future.”

It might sound strange that a state museum would dedicate an exhibition to two works that are owned by a private individual. Therefore, in order to dispel any qualms arising from possible prejudices about the too-often vituperative public-private relationship, a few considerations should be made. First of all, the two paintings by Daniele Ricciarelli da Vol terra (Volterra, 1509 - Rome, 1566) that will be housed until May 7 at the Roman exhibition venue are subject to a declaration of cultural interest (they are “notified,” as they say, or “subject to a protection restriction”), and for that reason, according to Article 65 of the Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape, they cannot be transferred abroad. Secondly, they are two works of very high quality by an artist whose catalog is rather sparse: those exhibited at the Corsini Gallery, in particular, are a valuable document for understanding how much the Volterrano had been affected by Michelangelo’s lesson (and in particular by the one he learned while observing the Last Judgment). Any opportunity to see them should therefore be welcomed. Finally, the two works are in the care of the Galleria Benappi in Turin and appear to be on the market: last year they were exhibited at TEFAF in Maastricht and, as the always timely Didier Rykner noted in the Tribune de l’Art, “certain American museums must have been particularly frustrated at not being able to acquire them.” Could the exhibition be a prelude to a hypothetical entry of the two works into Italian public collections? In the event that the operation might loom, we would be keen supporters. In case, on the other hand, it is a possibility that has not yet been considered, we take the opportunity of this review to throw a small stone in the pond.

|

| The room housing the exhibition on Daniele da Volterra |

|

| Window set up with biography of Daniele da Volterra |

So let us come to the extraordinary content of the exhibition, curated by Barbara Agosti and Vittoria Romani: two paintings, an oil on canvas and an oil on panel, which the public rarely has the opportunity to admire. An exhibition of only two works, but of great value, and not only because, apart from the aforementioned Dutch trip, the last exhibition of d’Elci’s paintings goes back to 2003, on the occasion of the monographic exhibition on Daniele da Volterra that was held that year at Casa Buonarroti and that was moreover curated by Romani herself, but also because at the Corsini Gallery the reflectographs are presented to the public that have allowed a more complete analysis of the two works from a technical and stylistic point of view. And again, because the exhibition is actually extended beyond the room in which it is set up thanks to the presence, in the museum itinerary, of two additional works, owned by the Corsini Gallery, created by artists who worked in the same cultural sphere as the exhibition’s protagonist. These are, in particular, an Annunciation by Marcello Venusti and a Holy Family once believed to be the work of Siciolante da Sermoneta but recently attributed to Jacopino del Conte.

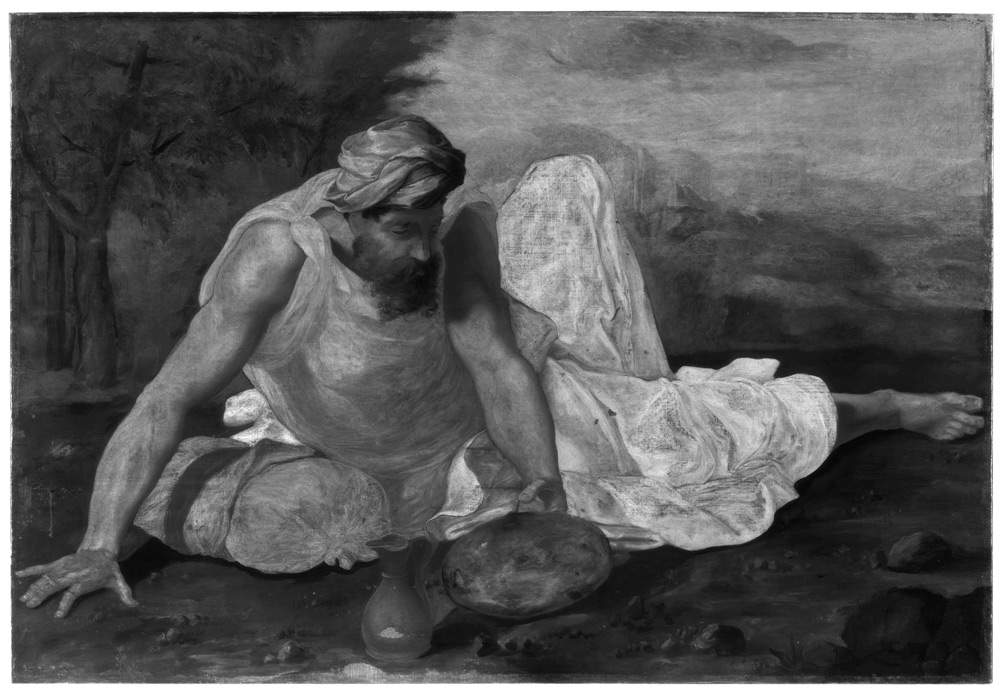

The d’Elci paintings are so called because they come from the collection of the Counts Pannocchieschi d’Elci of Siena, to whom the works came by inheritance from descendants of the same painter: until the early twentieth century, in fact, their presence was recorded in Volterra, in the Ricciarelli house, a location in which the works were given since the 1770s. Although probably little known to the public, d’Elci’s paintings, on the other hand, represent one of the cornerstones of critics’ efforts to reconstruct Daniele da Volterra’s artistic vicissitudes: both executed in Rome, albeit a few years apart, clearly demonstrate the stylistic relationships that the artist was able to entertain with his colleagues. The first, in chronological order, is theElijah in the Desert, an oil on canvas whose solitary protagonist, the prophet Elijah precisely, is lying on the bare earth, in the act of picking up, tried by his labors, a flatbread: the biblical account (from the Book of Kings, chapter 19) has it that Elijah received the food (next to the flatbread we notice a pitcher filled with water) from an angel who had taken care of him and who traditionally appears in paintings of similar subject (his absence from the painting exhibited in Rome is an unusual fact). The presence of the flatbread and water, foods explicitly mentioned in the Book of Kings and assimilated to the bread and wine that Jesus administered to the apostles at the Last Supper, recalls the theme of theEucharist, which, at the dawn of the Council of Trent, was at the center of heated debates that pitted Catholics against Protestants. The Lutherans, in particular, had denied the concept of transubstantiation, that is, the conversion, during Mass, of bread and wine into the body and blood of Jesus, affirming instead that of consubstantiation, that is, the simple co-presence of the body and blood of Jesus on the one hand and the physical nature of the two foods on the other. In Volterra, the cult of the consecrated host was particularly deep-rooted, in part because of a Eucharistic miracle that allegedly occurred in the city in 1472, when a soldier who had desecrated a pyx saw that the contents had taken to emitting dazzling rays and was shocked at what had happened. It is speculated that theElijah in the Desert was intended for Daniele Ricciarelli’s hometown in particular.

|

| Daniele da Volterra, Elijah in the Desert (c. 1543; oil on canvas, 81 x 115 cm; Private collection). Photo: Andrea Lensini, Siena |

|

| Daniele da Volterra, Elijah in the Desert, reflectography |

The majestic and monumental figure of the prophet occupies the entire horizontal axis of the painting: the fingers and toes even reach to touch both edges. In the grandeur of the strongly Classical-accented figure and in the iridescence of the squillant colors are evident the suggestions that Daniele da Volterra drew from the example of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel (particularly those in the vault), but these are not slavish imitations: the Volterran, who had been a schoolboy of Perin del Vaga (who, in turn, frequented Raphael’s circle) sought to mitigate Michelangelo’s vigor by softening it with a good dose of Raphaelesque grace evident notably in the mild landscape that is linked to the mighty figure of the protagonist with a very calculated study of lighting (note in particular the shadow cast by the tree in the background on Elijah’s left shoulder) and of the positions of the prophet’s limbs, to suggest three-dimensionality. Reflectography helped to make evident the care taken by Daniel of Volterra in the early stages of creation: as much as this kind of investigation knows some difficulties for paintings on canvas, in some places (for example, in the area of contrast between the landscape and Elijah’s left leg) it is possible to appreciate the fineness of the Tuscan artist’s drawing, and the captions well help the visitor to read the image obtained by infrared scanning (and also to explain why unearthing the drawing by reflectography, in works on canvas, is more difficult: because the way the canvas is prepared offers worse contrast conditions to make the preliminary studies stand out).

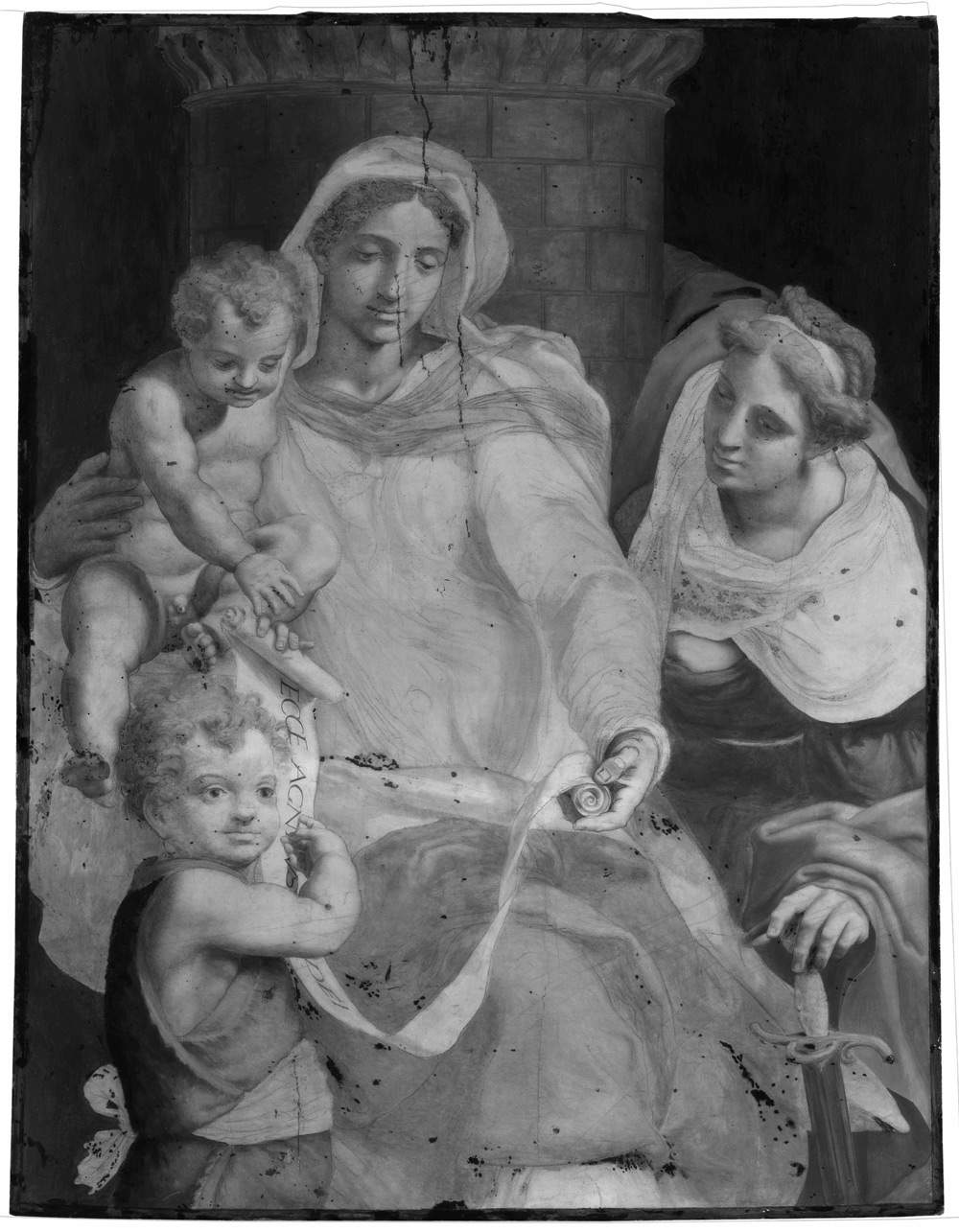

If theElijah in the Desert has been dated to a period close to 1543, the year in which Daniele da Volterra finished the frescoes in the church of San Marcello al Corso, d’Elci’s other painting, the Madonna and Child, St. John and St. Barbara, should be slightly later than the completion of the Deposition of the Trinità dei Monti, dating from about 1545: the hypothesis that finds most favor would have it executed around 1548. A tall tower stands out behind the protagonists: it is the one that the hagiography of St. Barbara wants to be the place of her imprisonment, before her martyrdom that took place at the hands of her father, who had not tolerated her conversion to Christianity and who beheaded her with the sword that later became the saint’s iconographic attribute (it is not missing even in Daniele da Volterra’s painting). The third element that helps to identify the saint without hesitation (in the past, on the other hand, some doubts were recorded: the names of St. Martina and St. Catherine of Alexandria were also proposed) is the naked breast, a reference to the tortures the young woman had to endure at the hands of her jailers (among them, precisely, the amputation of her breast, later healed by an angel).

|

| Daniele da Volterra, Madonna and Child, St. John and St. Barbara (c. 1548; oil on panel, 131.6 x 100 cm; Private collection). Photo: Andrea Lensini, Siena |

|

| Daniele da Volterra, Madonna and Child, St. John and St. Barbara, reflectography |

In the description of the painting in the 2003 monograph catalog, attention was drawn to theoriginality of Daniele da Volterra’s saints (and, in general, figures): in particular, the attempt to give a strong sense of detachment of the figures from the background would distinguish the Volterrano’s figures from those of his fellow countrymen, such as Vasari or Bronzino, active in the same years. More in detail, it quoted Hermann Voss, who considered such figures to be endowed with a “concreteness that is sometimes even disturbing,” to the point that “it almost seems as if they are trying to get out of the picture, with their abnormally large extremities” (the fingers, for Voss, were decidedly revealing features: note those stretched forward of Saint Barbara’s left hand, but also the right foot of the Child that is similarly brought toward the viewer). The figures seem almost to throw themselves forward, to make themselves meet the viewer, to involve him deeply. It is evident how Michelangelo’s undertakings in the Sistine Chapel and the Pauline Chapel exerted a fundamental attraction on Daniele da Volterra: the composition itself, with the figures literally “embedded” (such is the term used by the curators) in the painting so as to bring them to occupy the entire pictorial surface, is the result of a careful analysis of Michelangelo’s works. A composition, moreover, studied in every detail: and since the Madonna and Child, St. John and St. Barbara is a work on panel, reading the drawing through reflectography is a decidedly easier operation. It is clear, therefore, that the artist had produced an extremely detailed preparatory drawing: he had even taken care to draw from the cartoon, which was also clearly not lacking in detail, the boundaries between areas of light and shade in order to offer himself help in the realization of the chiaroscuro. A chiaroscuro, it must be emphasized, that is very refined: see, by way of example, the corbels of the tower that are flooded by the light coming from the right and then gradually slope toward darkness, or again the transitions on the face of Saint Barbara who, leaning out toward us who observe her (in a manner not without a certain sensuality, heightened by the exposure of her naked breasts), remains half in half in the half-light.

Leaving the room that houses the works of Daniele da Volterra (set up, moreover, with sober and elegant scenery: the full legibility of the paintings and the reflectographs has naturally been favored) it is necessary to proceed with some caution, because the dialogue with the works in the collection (particularly fruitful is the one with the Holy Family attributed to Jacopino del Conte, whose Madonna echoes that of Daniele da Volterra) is not adequately highlighted and one runs the risk of missing it, or at any rate of not paying due attention to it: in this sense, the organizers could have done decidedly better. Beyond this lack, it is in any case an operation to be promoted without delay, also because it is set within a context that encourages the visitor to go deeper: Palazzo Corsini is just a stone’s throw from Vatican City, where we find not only Michelangelo’s works that inspired Daniele da Volterra, but also the very frescoes that the Volterrano executed for the Vatican Palaces, and crossing the Tiber one can go and admire his works in Trinità dei Monti, San Marcello al Corso, and San Giovanni in Laterano. Besides, as already pointed out, this is an exhibition that offers an excellent opportunity to see two otherwise inaccessible sublime works by Daniele da Volterra. That is not to say that with just two paintings one cannot pull off aclever operation: in an age when exhibiting one or two works means, more often than not, setting up displays closer to religious celebrations than art exhibitions, events such as Daniele da Volterra. D’Elci’s paintings, impeccable from a philological point of view and valuable from a popularizing one, should be held up as virtuous examples.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.