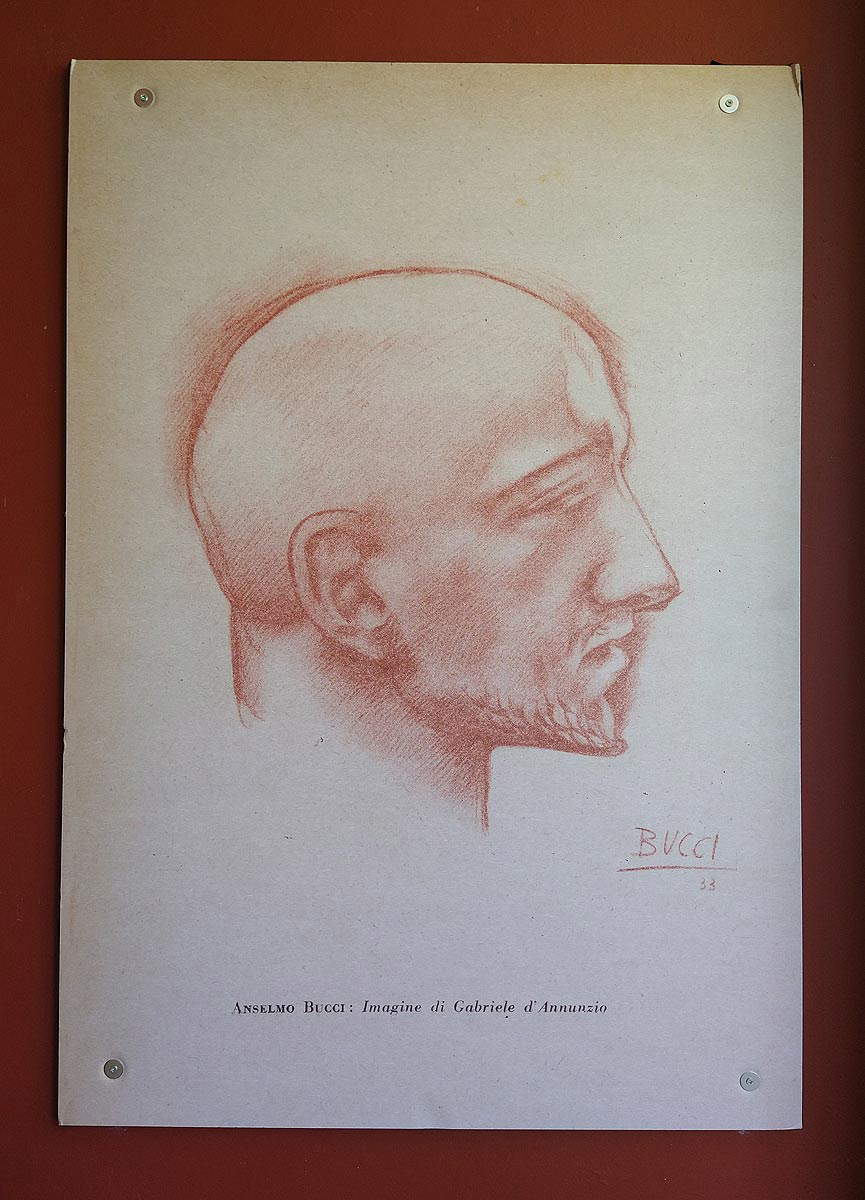

A small volume published in 1943 preserves the faded memory of the visit that Anselmo Bucci reserved for the Vittoriale ten years earlier: it was printed by Giorgio Nicodemi, an art historian, a tireless contributor to Emporium, bound to Gabriele d’Annunzio by a solid friendship and a long and intense correspondence. It was titled Testimonies for the Inimitable Life of Gabriele d’Annunzio and housed drawings by Guido Cadorin, who was among the Vate’s favorite artists, so much so that he was commissioned by the poet to decorate the leper’s room, that is, the most intimate and cozy room of the Vittoriale, and by Bucci himself, who contributed an image of D’Annunzio, a portrait of Eleonora Duse, a reproduction of Napoleon Martinuzzi’s statue of Victory placed above one of the Arengo’s columns(Et haec spinas amat Victoria), and an allegory of the Vittoriale itself. Beyond the notes Bucci traced in his notebook as he wandered around the Gardone Riviera mansion, no other evidence allows us to explore more deeply any, further links between the poet and the painter. The conductor Adriano Lualdi, another personage who knew D’Annunzio well, declared at a conference that he had no idea how receptive the Vate was to painting, but the mere fact that he “chose Cadorin and Bucci as his collaborators” at the Vittoriale could be considered a “most eloquent symptomatic fact.”

Was Bucci thus able to collaborate more continuously and closely with D’Annunzio, if Lualdi compared him to Cadorin, who certainly had a far from minor role in designing the Vittoriale’s apparatus? For now, we can content ourselves with seeing him return to the shores of Lake Garda: the exhibition Anselmo Bucci. Return to the Vittoriale, which D’Annunzio’s home is hosting until Sept. 21, recalls his visit in the summer of 1933 to bring a significant core of Bucci’s work to the spaces of Villa Mirabella, the early 20th-century building at the edge of the park that D’Annunzio bought in 1924 to make it first a guesthouse and then the residence of his wife, Maria Hardouin di Gallese. The exhibition, which is curated by the president of the Vittoriale, Giordano Bruno Guerri, assisted by Elena Pontiggia and Matteo Maria Mapelli, and with a scientific committee that, in addition to Mapelli himself, includes the names of Valentino Rubetti and Angelo Rampini, is immediately proposed as an attempt to critically relocate Bucci’s work. To use the words of Guerri himself, Bucci “deserves to regain his rightful place among the greats of the twentieth century,” and consequently “the Vittoriale degli Italiani is proud to contribute to this enterprise.”

There is little doubt that Anselmo Bucci is extremely underrepresented in our country’s public collections: many of his works are scattered among private collections, and the most important nuclei of visible works are divided between his native Fossombrone (but here, too, the credit belongs to a particular collector, Giuseppe Cesarini, who donated his home, where several works by the artist from the Marche region were kept, to the municipality) and the civic collections of Monza, the city where Bucci spent the last years of his life. Anselmo Bucci remained essentially forgotten for decades: it will be enough to remember that from the date of his death it would be almost fifty years before the public would have the opportunity to visit an exhibition dedicated to his work, except of course for the few exhibitions of local scope. And few, too, were the group exhibitions in which his paintings were offered. One could justify this oblivion by recalling the damnatio memoriae in which many artists more or less close to Fascism incurred, but one could also find the reasons for the lack of attention to him in his own art, given his nature to dwell little on his achievements: they had nicknamed him the “flying painter” for his propensity not to plant roots in one place, and he had used that nickname as the title of his autobiography, published in 1930 and appreciated to the point of earning him victory at the first edition of the Viareggio Prize. And another reason could be found in the voluntary isolation into which he retreated after the war, given the sidereal distance that distanced him from both sides of the abstract-figurative diatribe that had emerged in those years.

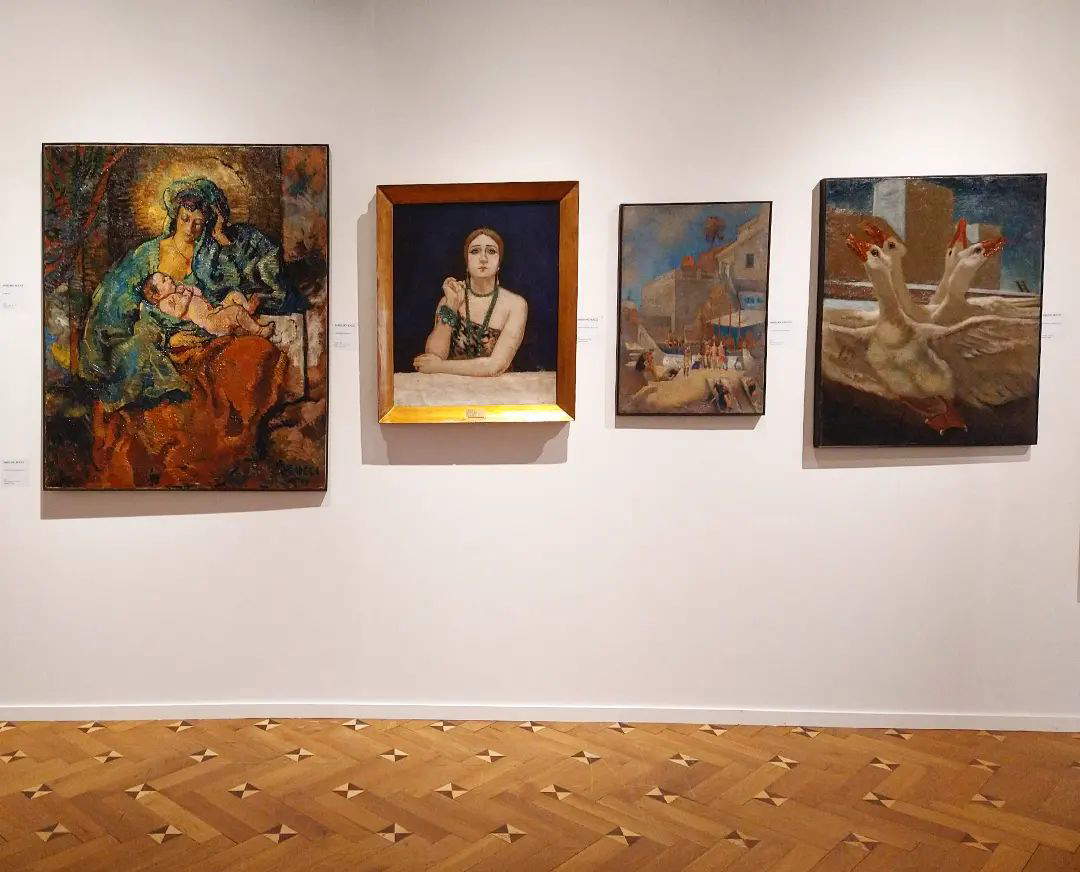

It is natural, then, that it rarely happens to come across a work by Bucci in a public museum, given the scant consideration given to this painter, who was nevertheless the most original, restless, and versatile original, restless, versatile and ironic soul of the Novecento group (it was he, moreover, who invented the name of the movement baptized by Margherita Sarfatti), and given also the acquisition policies of Italian public museums since the postwar period, notoriously uncaring with regard to contemporary art and twentieth-century art, as if the vicissitudes of the arts in Italy had closed after Romanticism. And yet, as early as 2003, in the margins of one of the first surveys of Bucci’s art, a scholar like Rossana Bossaglia took care to point out that "the role played by Bucci in the Italian artistic panorama of the twentieth century is much more significant, as a testimony and as a stimulus, than is usually remembered. A role that emerges with supreme clarity as one walks through the large hall of Villa Mirabella that houses the most significant part of the exhibition, the one in which the paintings are lined up, divided into four fundamental moments, each of which occupies a wall: the years of the first experiments and the first stay in Paris, those of the Novecento group, the research of the 1930s, and the paintings of the war. Four moments to give the visitor an account of the extreme variety of an erratic and protean career.

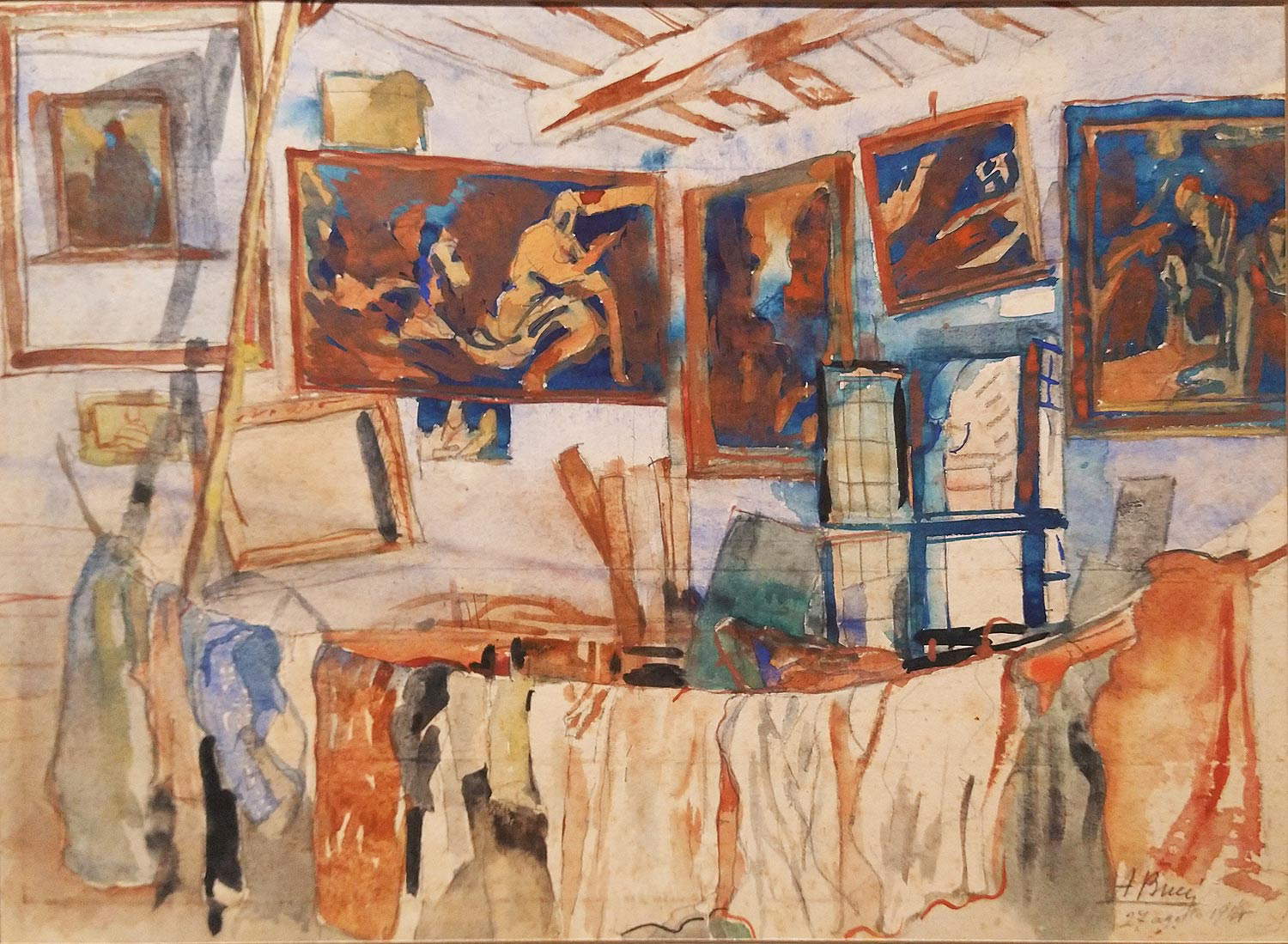

The itinerary begins with the Paris years, those between 1906 and 1914, with the first paintings oriented toward the results of French art of the time: at the opening of the exhibition here is The Furlo Gorge, an original and unpublished landscape poised between Impressionism and the poetics of the sublime; here is the watercolor with theInterior of the Paris Studio, also unpublished, which looks at the cursive painting of a Degas but declining it in terms of further immediacy, here is a view such as the Studio of Brittany, a sort of synthesis between the Impressionism of the first hour, although declined according to that language "too volumetric and solid compared to the orthodoxen plein air " (so Elena Pontiggia in her essay in the catalog) that tended to distance it from the taste of the French, and the new research on forms and volumes inaugurated by Cézanne.

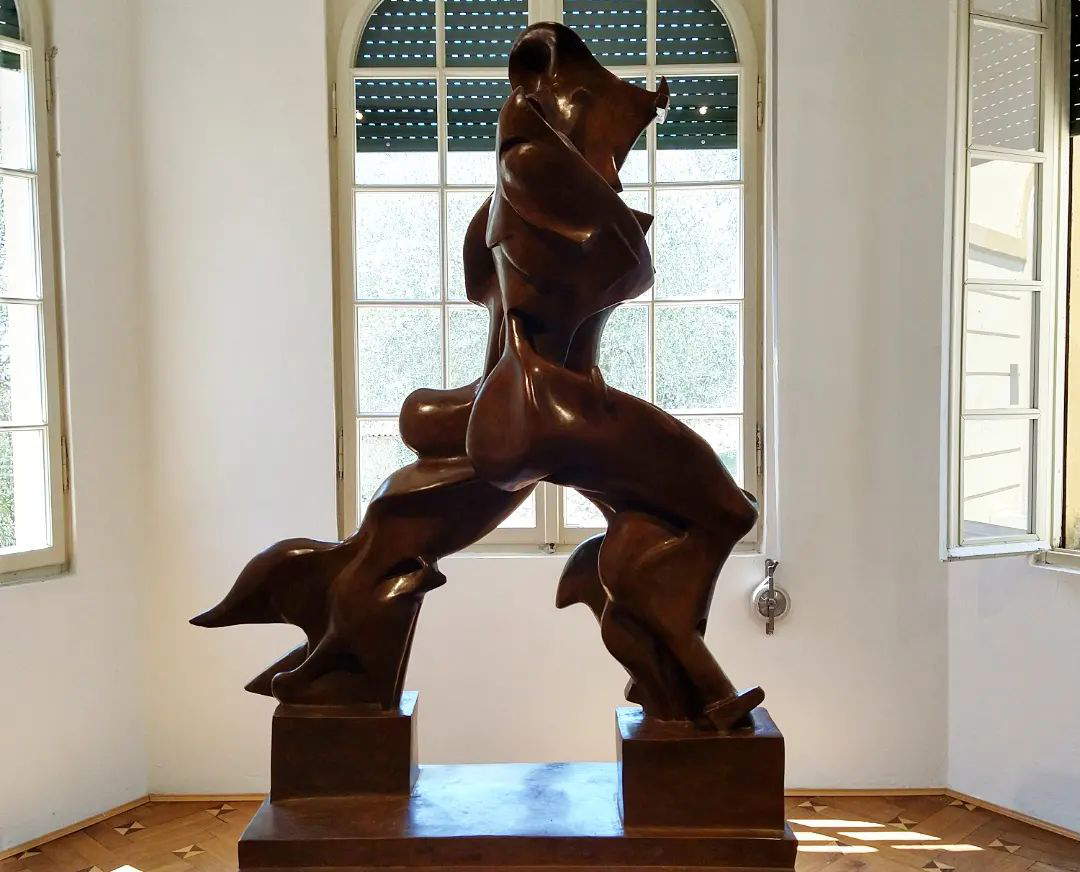

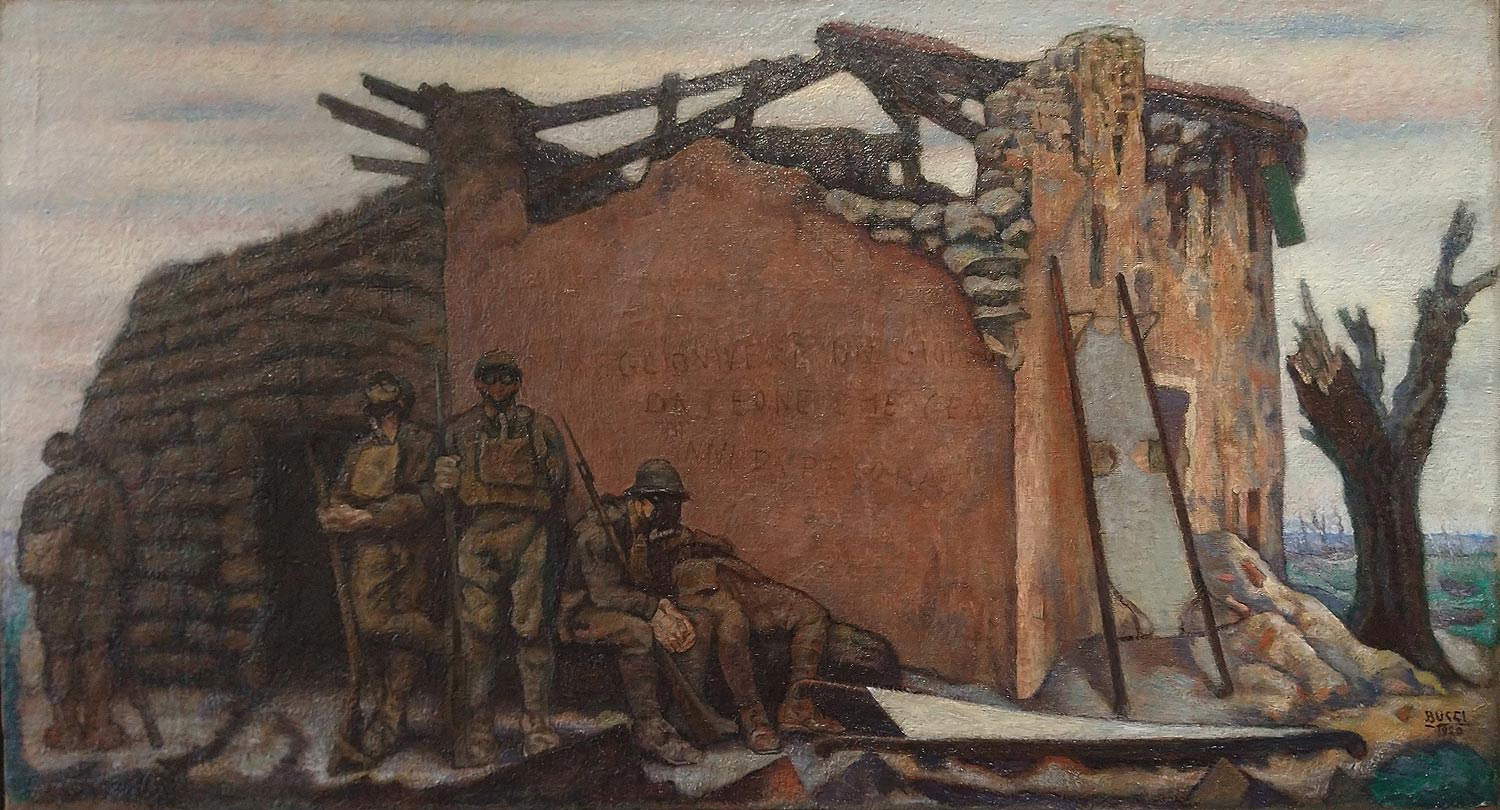

His return to Italy coincided with the events leading up to the First World War: Bucci, an interventionist, enlisted in the Volontari Ciclisti Automobilisti battalion where he had found an enthusiastic handful of Futurists (Marinetti, Boccioni, Russolo, Sant’Elia and others) and took part in the hostilities, both as a soldier and as a war painter, an activity he indulged in during the breaks between the fighting. The results of his work can be seen along the wall leading to the large window overlooking the garden: The Hero’s Funeral is a painting that is still solidly Impressionist, from which a deep bitterness emerges and where, the aforementioned Nicodemi already wrote in 1941 in an article in Emporium dedicated to the soldier-painter Bucci, “the indifference of the houses and deserted streets through which the funeral convoy passes seems to burden him as if with its own pain.” The closeness to Boccioni, with whom Bucci would later be befriended (a fusion of the Unique Forms of Continuity in Space that closes the room is intended to evoke this bond and the suggestions it could provide to the Marche painter) led him to make an isolated Futurist experiment, the 1917Farewell, a work in which one observes a woman (who is none other than Juliette, Bucci’s fiancée at the time) who, waving a white handkerchief, bids farewell to departing troops: Bucci approaches the Futurists superficially; his idea of movement is limited to the repetition of the outline of the hand to suggest the young woman’s gesture, but there are no decompositions of planes, no interpenetrations of objects, and his language remains entirely alien to the “force-lines” that were instead the cornerstone of his friend’s poetics. Bucci, at most, is content to confuse the landscape with the girl’s dress, although the marked contours of the volumes unequivocally establish that the organization of space and figures still responds to traditional criteria. A further point of approach will be counted in his production in 1920, in which Bucci barely touches futurism, to which he approaches more by thematic choices than by elaboration of formal solutions: it is the painting In volo, which anticipates by a few years the beginnings of Futurist aeropainting, and is absent from the exhibition, however, since it was exhibited in conjunction with the exhibition on aeropainters held at the Labirinto della Masone in Fontanellato. The return from the war marks a decisive change of pace, demonstrated by Millenovecentodiciotto, perhaps one of his best-known works, which depicts a group of soldiers standing in front of the rubble of a destroyed house (complete with the slogan “Better to live a day as a lion than a hundred years as a sheep”): Bucci’s gaze abandons the avant-garde and prepares to reread tradition.

Anselmo

Anselmo Anselmo

Anselmo Anselmo Bucci,

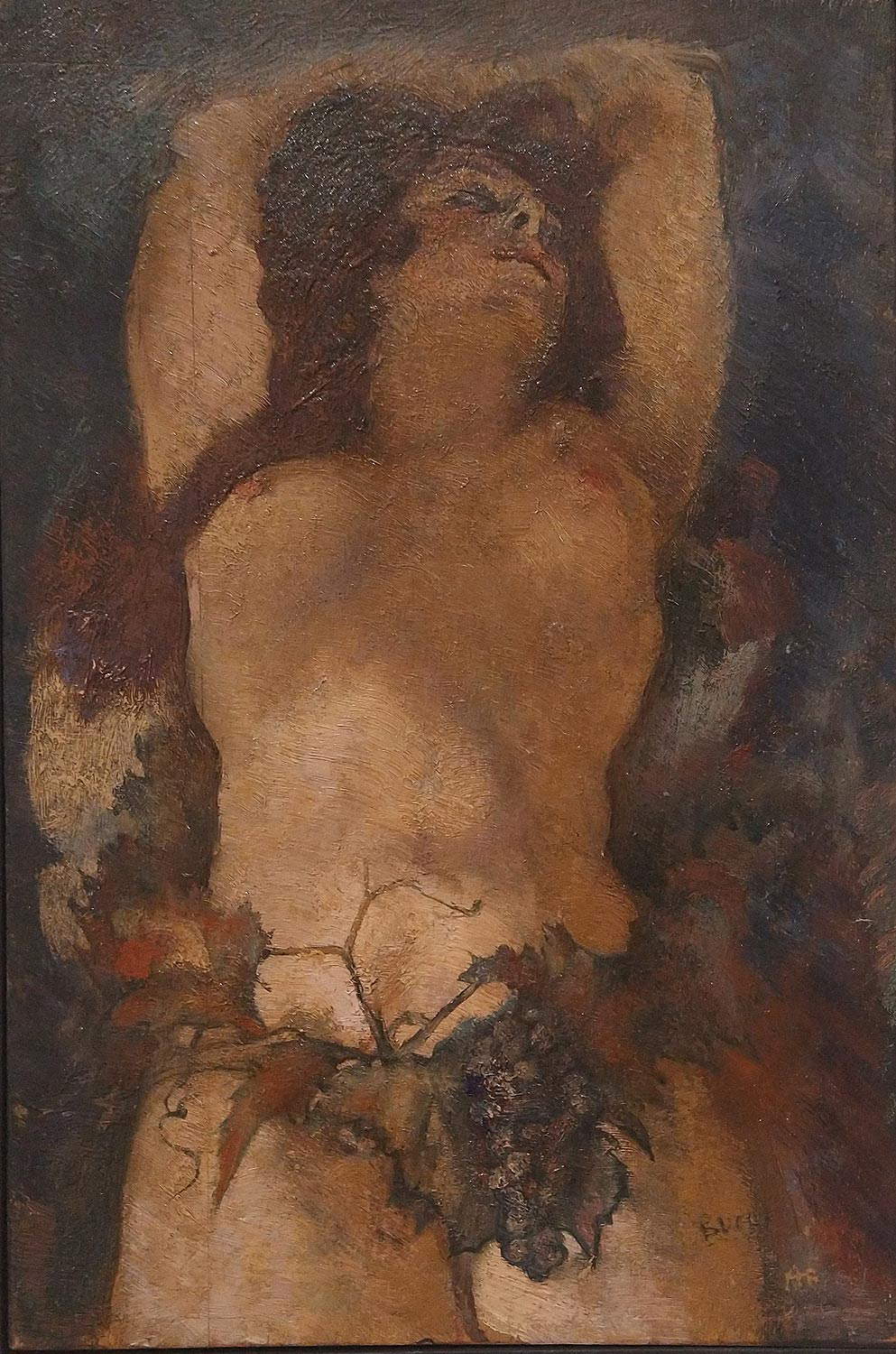

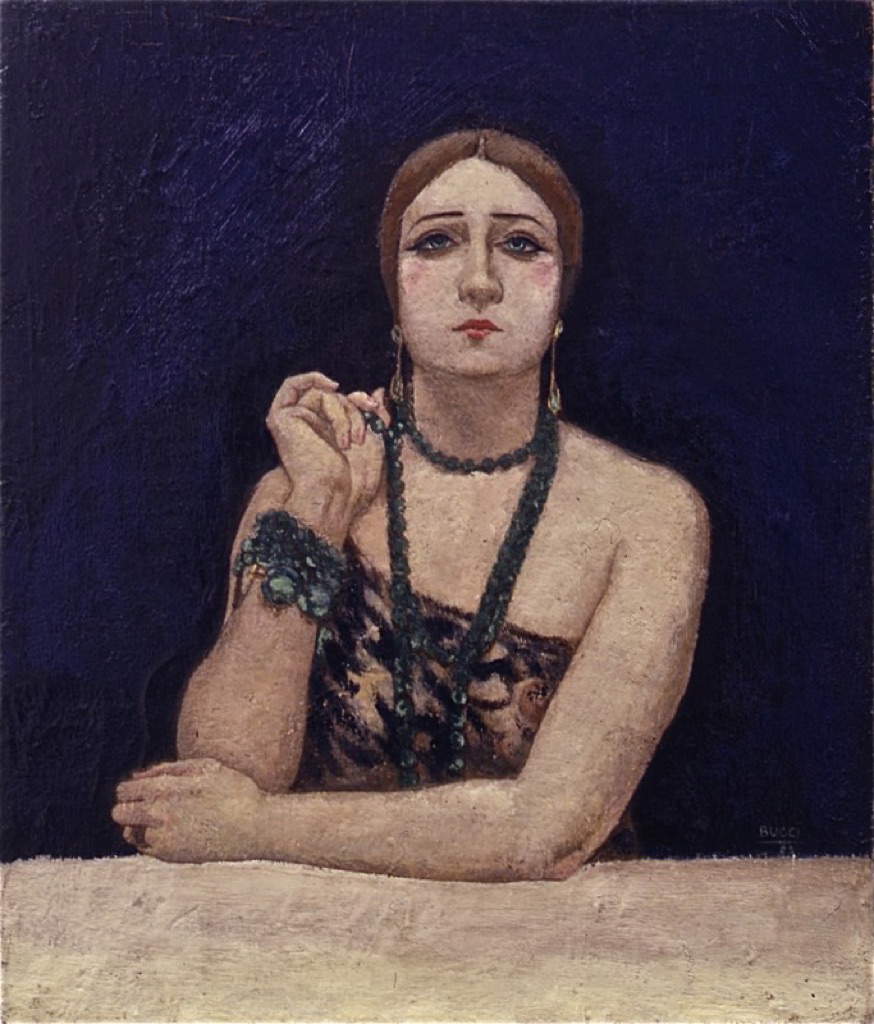

Anselmo Bucci,It was Anselmo Bucci who, after spending some time in Venice, fell in love with Titian’s art and produced a masterpiece such as The Surprised Lovers, with a scene that, Pontiggia writes, “is freely inspired by the great compositions of sixteenth-century Venice, also taken up in later centuries, depicting the adulterous loves of Mars and Venus, discovered by Vulcan.” Venetian colorism and the modern transposition of a classical subject combine with memories of seventeenth-century Spanish painting, which Bucci must have seen at the Louvre, and the compositional virtuosity that gives rise to perhaps the most daring of all the Marche painter’s painting to render the soft, full physique of a beautiful woman, nude, who is emphatically possessed by her lover, caught clutching her breast, while further back the betrayed consort (the “Mr. Celestino” who “missed the train,” as the ironic handwritten inscription on the verso of the painting reads) pulls back the curtain and indulges in a bovine expression of astonishment. The passion for the female body is also appreciated in the 1921 Bacchante, another work presented to the public for the first time, dense with art nouveau memories, though never as much as the portrait of Rosa Rodrigo, also known as La bella, painted two years later: Titianesque portraiture, complete with literal quotation (the parapet such as that of the Schiavona or the so-called Ariosto, including the leaning elbow), provides Bucci with the cue to paint a kind of archetypal portrait of the femme fatale of the 1920s, with the fixed, enigmatic gaze, her thin, carefully shaved eyebrows, her eyes marked with abundant kajal, her lips accentuated by lipstick applied to form a heart, her hair pulled back with parting in the middle, and a see-through dress worn to tickle the male’s appetites.

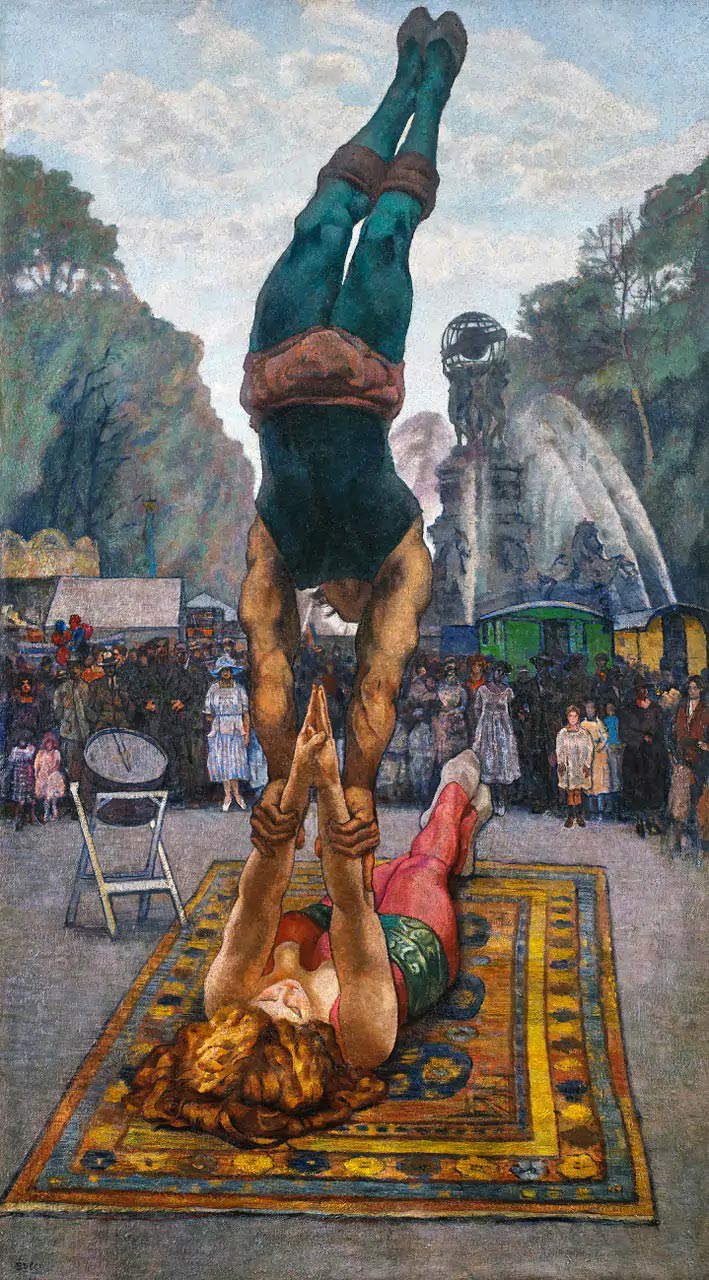

Instead, modern life enters paintings such as Odeon or The Jugglers, which are among the most authentic and lofty manifestos of Bucci’s painting of the 1920s: in the animated vision that underlies the former, Bucci implicitly declares the elements around which his Novecentist poetics revolves, namely, the vigor of drawing (note again the outline), solid plasticism, the centrality of the human figure, the rejection of any extreme point that might have come from the avant-garde, and the references to the art of the past, and in particular that of the Renaissance. It sometimes happens that the art of the past is mentioned simply for reasons that have nothing to do with the formal values of the painting, as happens in the Jugglers, since one notices in the background, in the distance, the profile of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s Fountain of the Four Parts of the World, inserted to establish a visual and symbolic link between the acrobats and the women who, in Carpeaux’s sculpture, hold up the vault of heaven, as if to say, according to Pontiggia, that our existences rest on fragile foundations. The prominence of the human figure also characterizes a masterpiece like The Painters, another flagrant statement of poetics, where ancient and modern meet in one of the cornerstones of Anselmo Bucci’s production. Against the backdrop of the Fossombrone that gave him birth (the Concordia Bridge and the Ducal Palace are easily recognized there), Bucci portrays himself with a paintbrush in one hand and a cigarette in the other: his figure stands out imperiously against the landscape, the pose is three-quarter-length as was customary for self-portraits of ancient artists, but without lacking irony the painter portrays himself in work settings and with a half-full glass of whiskey just below his brushes. The sharpness of the landscape, its earthy colors, robust outlines, and the timely separation of sky and earth denote the reference to 15th-century painting and sanction the definitive departure from the avant-garde, while at the bottom the cartouche with the inscription “Vera immagine di Anselmo Bucci da Fossombrone” brings to mind the way Venetian painters of the 15th and 16th centuries used to sign their works. Bucci self-signs along with a helper, which gives him a way to quote Titian again: the tray is that of the Girl with Tray of Fruit, a probable portrait of his daughter Lavinia, preserved in the State Museums in Berlin.

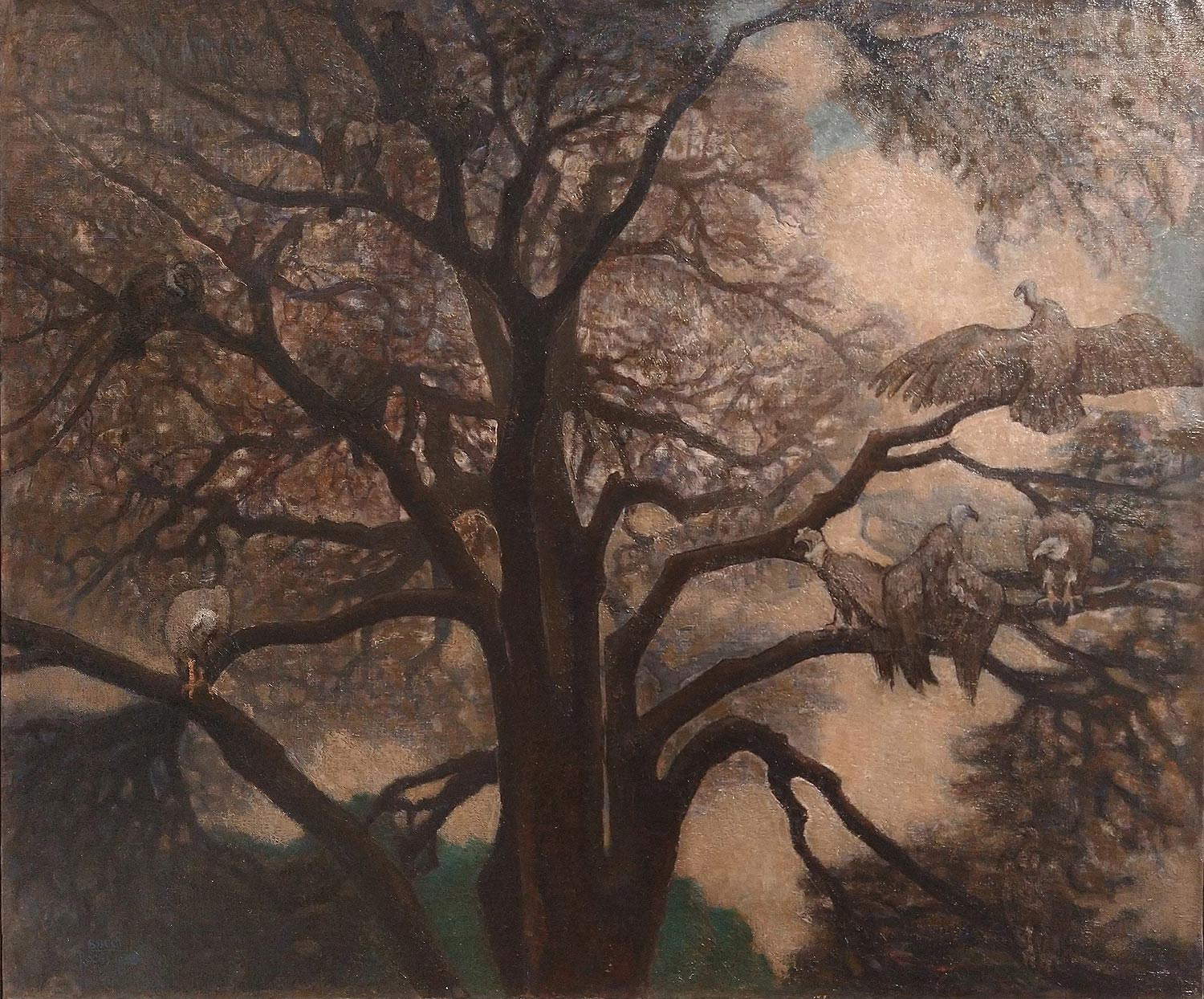

The first signs of a new expressiveness are felt beginning in the mid-1920s: take, for example, the Cedar of Lebanon, which can be considered a work of rupture, a painting that can be compared to the view of a forest of which the critic Luigi Serra had spoken, stating that similar paintings, with the view from below and the branches silhouetted against the sky following almost geometric shapes, “all aim at the effect and try to astound rather than move.” It is a painting that becomes decidedly more synthetic, as one realizes when observing Sea Noon, which marks a return to a search for light, forms and volumes, to which Bucci will be committed for much of the fourth decade of the century. My Study in Paris, another unpublished work from 1935, unveils itself to the relative with its bigia chromatic range, which distinguishes Bucci’s production in these years, with a formal synthesis mindful of post-Impressionist research, and with delicate chiaroscuro effects that become further protagonists in Primavera, an interior view with figure and bouquet of flowers on the table, a probable recollection of Vangoghi. The path among the paintings closes with a last unpublished work, Tetti di Milano, “a marvelous landscape expressed in a myriad of signs” (Pontiggia), and with the Studio per il violoncellista Crepax, a powerful and resolute painting with a vague expressionist hint, and which moreover closes the circle, since Gilberto Crepax, the musician portrayed by Bucci, knew Gabriele d’Annunzio and had a brother who was part of the Vittoriale quartet.

Anselmo

Anselmo

Anselmo Bucci,

Anselmo Bucci,

Anselmo

Anselmo Anselmo Bucci,

Anselmo Bucci,

The exhibition ends in the adjoining room, where the curators have displayed, by way of a tasty appendix, photographs, dedications, postcards: worth mentioning, in particular, is a photograph of the Spasimo, a painting whose traces have been lost, and which well documents the genesis of Surprised Lovers. Finally, part of the itinerary is also a showcase displaying for the first time to the public some unpublished documents of the Curia, a goliardic association (visitors will realize this simply by reading the texts) that Bucci and Dudreville had formed in 1920 together with the sculptor Enrico Mazzolani and the poet Diego Valeri. One of the highest merits of the Vittoriale exhibition consists precisely in the presentation of a great deal of material that has never been published, both in the exhibition and in the catalog: in the volume accompanying the exhibition, for example, there is an account of a singular pastiche from 1910 (unfortunately not on display in the exhibition), an intervention by Bucci on a seventeenth-century painting from the school of Pietro Liberi, in which the painter adds his own self-portrait to an allegory, substituting himself for the figure of a dog.

So much copy of unpublished material, moreover, gives a precise sign of how much study is still to be devoted to the figure of Anselmo Bucci, who, after all, can be said to have been rediscovered only in the last two decades, with many exhibitions of mainly local level, but still with sporadic occasions of wider appeal: the Vittoriale exhibition, in addition to being one of the most remarkable exhibition events held this summer in Italy, certainly marks a leap forward in the critical reappraisal of the Fossombrone painter. There are, to be sure, some revisable aspects (in fact, there is a lack of room apparatus capable of leading the non-expert public to a fuller understanding of Bucci’s poetics), but the exhibition itinerary, which offers itself to the visitor in the clarity of its diachronic development through the Marche artist’s art and which is presented with some of the fundamental masterpieces, has cleverly constructed to offer a significant anthology, and consequently allows one to derive a rather complete idea of Anselmo Bucci’s multifaceted activity and his views on art and life. All of this is supported by a catalog that stands as a very useful tool for study, given the presence of a complete bibliographic survey and the list of all the exhibitions, solo and group, in which Bucci took part. There is no doubt that the Vittoriale exhibition is to be seen as a new starting point, a new and remarkable stage in the long and continuous path of rediscovery of the Marche painter, which we imagine will gain new momentum. With the further hope that initiatives such as the Villa Mirabella exhibition will help to turn even more lights on one of the most interesting seasons of 20th-century arts in Italy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.