Cities of the Grand Tour: a beautiful exhibition without big names

The Giorgio Conti Foundation in Carrara continues its 2016 programming with what we can consider the year’s flagship exhibition, Grand Tour Cities from the Hermitage and Apuan Landscapes from Italian Collections, curated by Sergej Androsov and Massimo Bertozzi. This is the second exhibition of ancient art after last year’s exhibition on Canova: but important steps have been taken. If last year’s exhibition seemed to rest on rather shaky foundations and to focus almost exclusively on the “name-catching” Antonio Canova, reducing the rest almost to a mere side dish, moreover held up without an apparent philological project, the exhibition on the Cities of the Grand Tour has something to tell, and in particular recounts the season of the great trips to Italy during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when Italian cities were essential stops on the Grand Tour, the “tour of Europe” that the young scions of the most refined families (mainly from England) made to train, educate and learn.

The narrative is less about the journey itself than, precisely, about the stages of the journey. The title says it well: “Cities of the Grand Tour.” And protagonists are in fact the cities, painted by the artists who came, also from all parts of Europe, to train themselves on the art they could admire in Italy, from the vestiges of classical art to the masterpieces of the greats of the Renaissance and beyond. The exhibition, through paintings, reconstructs the atmosphere of the 19th century in Italian cities, proceeding with a tour that opens with an “introductory” room, so to speak, continuing with three rooms that group works divided by city (in the first paintings on Rome, in the second we move on to Venice and Naples, in the third other cities such as Milan, Genoa, Florence and Pisa) and ending in the hall that houses Apuan landscapes instead: if the works in the first part of the exhibition come from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, in the second section we find instead paintings and drawings that come from collections that are often inaccessible to the public (State Archives, Collections of public institutions, private collections). One might feel a sort of clear caesura between the two sections, but let us not forget that the Apuan lands often constituted an obligatory passage for travelers arriving from Northern Europe on their way to Rome or inSouthern Italy, and it not infrequently happened that painters lingered to paint what they observed in our areas, attracted by the rugged and austere beauty of the Apuan Alps, the castles dominating from the heights of the hills, the evocative tranquility of seaside villages such as Lerici or the villages at the mouth of the Magra, and the hard work of the quarrymen who transported marble from the mountains to the beaches where they were embarked.

|

| Exhibition “Grand Tour Cities from the Hermitage and Apuan Landscapes from Italian Collections” |

|

| Exhibition “Grand Tour Cities from the Hermitage and Apuan Landscapes from Italian Collections” |

|

| Exhibition “Grand Tour Cities from the Hermitage and Apuan Landscapes from Italian Collections” |

The itinerary opens, as mentioned, with a room that serves as an introduction and features 17th-century paintings, demonstrating that the allure of Italy seduced painters long before the practice of the Grand Tour was born. And it is an introduction of great importance because it clearly gives us an account of what elements contributed to making Italy a land coveted by travelers from all over Europe: among these elements, the one of greatest interest at the time was probably the Roman past. Thus we have a pair of views by Hendrik Frans van Lint, a painter who, upon arriving in Rome, decided to settle there: in what was then the capital of the Papal States, van Lint fused his passion for antiquity with that for genre scenes, creating lively views of ancient ruins dotted with figures intent on a wide variety of activities (in the exhibition we have two Views with the Arch of Titus and the Palatine in Rome dating from the first decades of the 18th century). However, the passion for antiquity is also represented by the one who, in the first half of the eighteenth century, was perhaps its greatest exponent, namely Giovanni Paolo Pannini (the curators of the exhibition preferred the spelling Panini): he is certainly the most important author among those in the exhibition, who exhibits one of his paintings with Ruins with the scene of the Apostle Paul’s preaching from 1744 (because ancient ruins often became a pretext for setting scenes of various characters, in this case a religious scene). A further element of interest to foreign artists was the colorful life of Italian cities, as evidenced by Johannes Lingelbach’s 1672 Market in the Square or Jan Miel’s Charlatan , another name of weight in the exhibition.

|

| Giovanni Paolo Pannini, “Ruins with a Scene of the Preaching of the Apostle Paul” (1744; oil on canvas, 63 x 82 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

Rome is the great protagonist of the next room: not only views of the monuments that fascinated visitors then as much as they fascinate visitors today (the View of the Colosseum by another important name, the Frenchman Hubert Robert, is not to be missed), but also public ceremonies, such as the one that the Florentine Antonio Cioci depicts in Festeggiamenti davanti al Palazzo del Quirinale of 1767 (this is theimage chosen for the exhibition’s poster and depicts, with an abundance of detail and a certain flair for narrative, the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the pontificate of Clement XIII, who looks out of one of the large windows of the Quirinal Palace, then the papal residence) as well as passages of popular religiosity (the evocative nocturne of the Prayer to the Virgin Mary by Englishman Joseph Severn reaches unsuspected heights of lyricism: it is surely one of the most poetic paintings in the exhibition). Also worth mentioning is a view by Ippolito Caffi, a sort of Canaletto of the 19th century, depicting Castel Sant’Angelo with its bridge and, in the background, St. Peter’s Basilica: the artist’s sensitivity reproduces on the canvas the light effects of a splendid Roman sunset over the waters of the Tiber, where the buildings almost act as a spectacular backdrop.

|

| Hubert Robert, “View of the Colosseum” (c. 1762-1763; oil on canvas, 98 x 135 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

|

| Antonio Cioci (Cioci Fiorentino), “Celebrations in Front of the Quirinal Palace” (1758; oil on canvas, 74.5 x 96.5 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

In the room devoted to Venice and Naples , views prevail: evidently, the wonder that painters must have felt when faced with Campanian landscapes or the magic of a city built on the lagoon was such that any further presence could almost be considered superfluous. Here, then, is a romantic View of Montesarchio, a village not far from Naples, executed in 1791 by the German Jakob Philipp Hackert, who for seventeen years, from 1782 to 1799, was active at the court of Ferdinand of Naples, but also a View of the Grand Canal made by a Venetian, Antonio de Pian, a vedutista trained in the painting of Canaletto. The section on Venice is also interesting because it offers us the only painting in the exhibition that bears witness to a trip by a family of the European aristocracy: it is The Tolstoy Family in Venice painted by another Venetian, Giulio Carlini, in 1855. In the painting we observe members of the family of Count Ivan Tolstoy (this was a different branch from the one from which the great writer Lev Tolstoy came), a member of the court of Tsar Alexander I of Russia, waiting to board a gondola: these paintings were expressly requested by travelers who, bringing home works such as the one exhibited in Carrara, intended to preserve a memory of their experience in Italy. Also worth mentioning is a Concert in a Gondola by the German artist Friedrich Nerly: against the backdrop of a sunset flooding the Venice lagoon with red, Nerly depicts in the foreground two boats on which several young people are seated intent on playing and singing. Knowing that these joyous and happy atmospheres could be breathed in Italian cities was also a source of attraction for travelers: suffice it to say that, in one of his letters, the great Chekhov provides a bewitching description of a Venetian evening, speaking of it in enthusiastic tones.

The next room takes us on a true “tour of Italy” thanks to a number of works, including an Interior of the Camposanto Gallery in Pisa by Giovanni Migliara (this is 1831), with the painter self-portraying in the right corner of the painting, a curious Veduta sulla Piazza del Duomo by the Lombard Angelo Inganni that almost makes us experience a typical day in the Milan of the19th century, and again the delicate watercolors (the only ones in the exhibition) by the Swiss Rudolf Müller and Friedrich Horner, who instead take us to Genoa offering views of the city from the terraces of luxurious villas or gardens with leafy pergolas, and finally the views of Florence by another Swiss, Friedrich Wilhelm Moritz.

|

| Carlo Bonavia, “The Bay of Baia” (second half of the 18th century; oil on canvas, 83 x 151 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

|

| Rudolf Müller and Friedrich Horner, “View of Genoa from Villa Negri” (ca. 1830-1840; watercolor on paper, 31.3 x 43.7 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

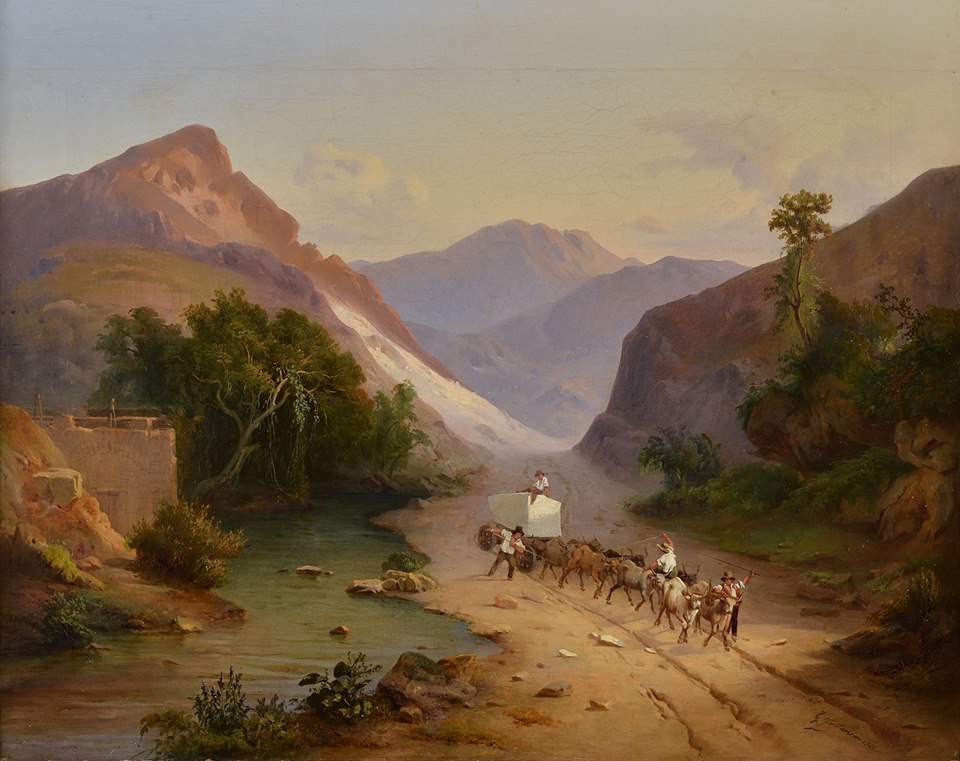

The last section, as anticipated, is reserved for Apuan landscapes from Italian collections. It is a true “exhibition within the exhibition,” displaying works by artists who came from afar (such as William Paget and Elizabeth Christiana Fanshawe) and Italian masters (Saverio Salvioni, Antonio Puccinelli and, above all, Giovanni Fontanesi, who is present in the exhibition with a large number of works that testify to the love that the painter from Reggio Emilia had for our lands, and that offer a rare opportunity to delve into his art) with one common denominator: representing the beauty of the territory of Massa and Carrara and its surroundings with drawings, watercolors, paintings.

|

| Giovanni Fontanesi, “Transporting Marble from the Apuan Quarries” (1845; oil on canvas, 49.5 x 62.5 cm; private collection) |

An intelligent exhibition that deserves a thorough visit: the audio guide offered with the entrance ticket (the cost of which might seem high to some, but the visit pays off), although it sometimes repeats what is written on the panels, is a useful tool to be led to the discovery of the paintings, because the texts were written with a certain predisposition toward storytelling, and in addition to pitting data on the paintings the voice also attempts to tell the story behind the painting (here, if we really want to find a flaw, common to other exhibitions at Palazzo Cucchiari as well: sometimes it is not clear whether on a panel we are reading a catalog card, or whether the texts of the panels have been included in the catalog). If we want, it is also an original exhibition: exhibitions on the Grand Tour have already been seen galore, but it is not often that one encounters exhibitions on this subject that prefer to focus on a single collection (that of the Hermitage) and that, from an expanded view, then narrow the discourse to tie the themes of the exhibition to the territory, accomplishing, moreover, a further operation of enormous interest. The accusation is often made, especially at certain major events, that they do not take into consideration at all the territory within which they take place: this has never happened at Palazzo Cucchiari, and it does not happen even for City of the Grand Tour , which shrewdly makes us aware of the fact that our areas, the territory hosting the exhibition, were a sort of obligatory passage for those who traveled to Rome or Florence. And perhaps before the exhibition, we could not even imagine how much our territory, now mistreated and sometimes even despised out of all proportion, was able to seduce travelers who came here from places we probably would not even be able to place properly on a map.

Click here for all the info on the exhibition

|

| One of the illustrative panels |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.