Children's games from around the world. Francis Alÿs' poetry at the Venice Biennale

Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Aug. 21, 2021. On the shore of a mound formed by the waste materials of a cobalt mine, a child, dressed in a yellow and green soccer shirt and a pair of red shorts, climbs up pushing the dusty tire of a truck in front of him. Behind him, the industrial plants. In front, the climb. His gaze is serious, focused, fixed; the camera frames him frontally for a good fifteen seconds, and he never blinks, intent on carrying the tire as high as he can. The camera then catches him from a distance: the pile of debris is so high. At one point he stops, evidently satisfied with the height he has reached, or fed up with too much work, we don’t know. He huddles inside the tire and plunges down: the wheel proceeds at speed, he holds on with his hands, the trajectory is perfect, the improvised vehicle does not swerve, he is calm. Three little friends chase him, the ride ends: then, together, they repeat the whole thing all over again, taking turns pushing the wheel, and singing a song.

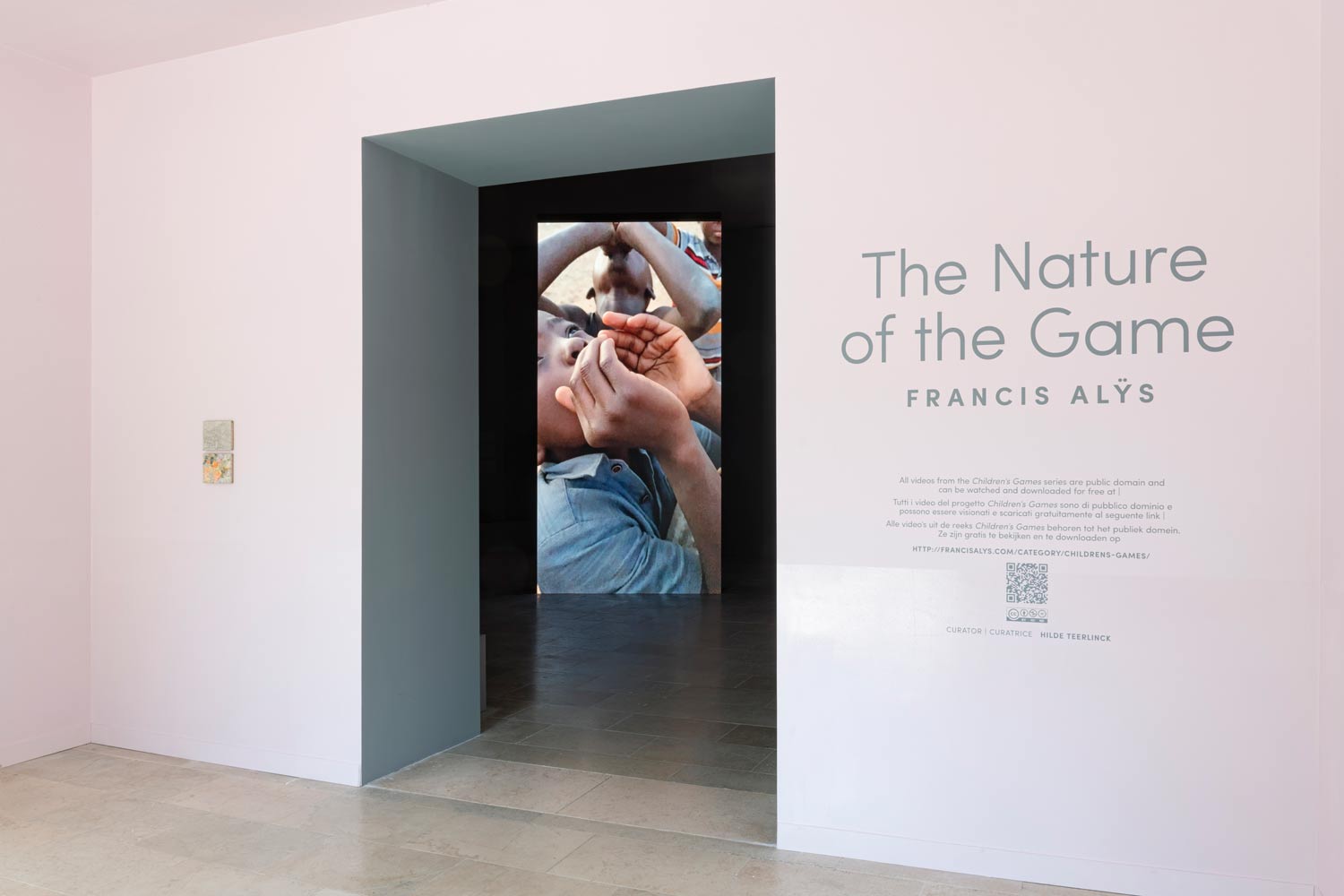

This is the sequence that Francis Alÿs filmed subjectively in the video La roue, one of the new chapters in the Children’s games series, shot over the past two years and then taken to the Venice Biennale, where Alÿs was entrusted with the Belgian Pavilion this year: the Flemish artist responded with the exhibition The Nature of the Game, curated by Hilde Teerlinck, a kind of summation of the work on children’s games that Alÿs began in 1999. Venice audiences already familiar with Alÿs will therefore see nothing particularly revolutionary: if anything, an extension, a series of additional chapters, an expansion of a project of relatively immediate understanding is proposed at the Giardini della Biennale. For more than two decades, Alÿs, who started in Mexico, has been going around the world filming children at play: from Belgium to Canada, from Afghanistan to Hong Kong, from Nepal to Venezuela, from France to the Congo, Alÿs has traveled to almost every continent to observe little ones in their playful activities.

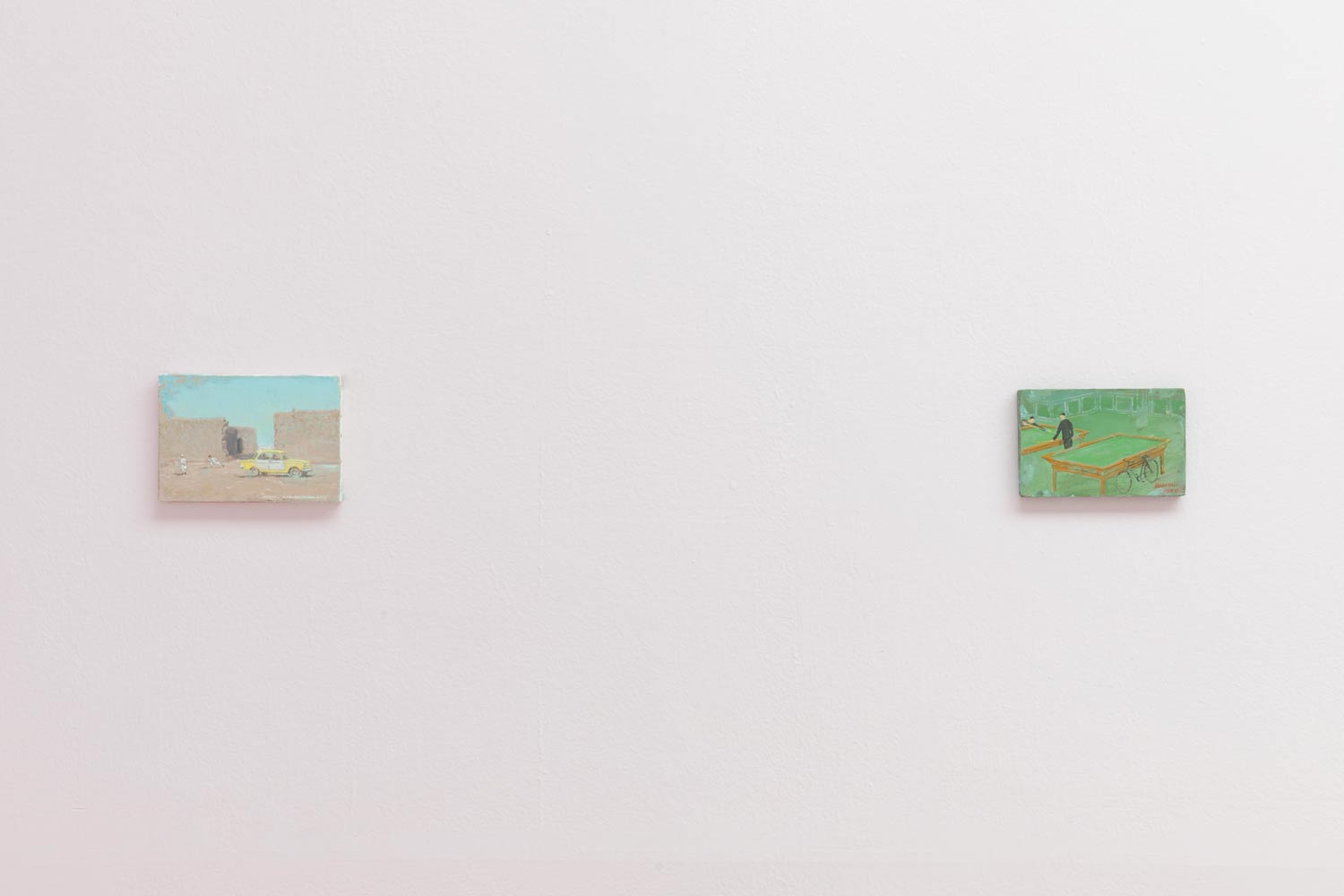

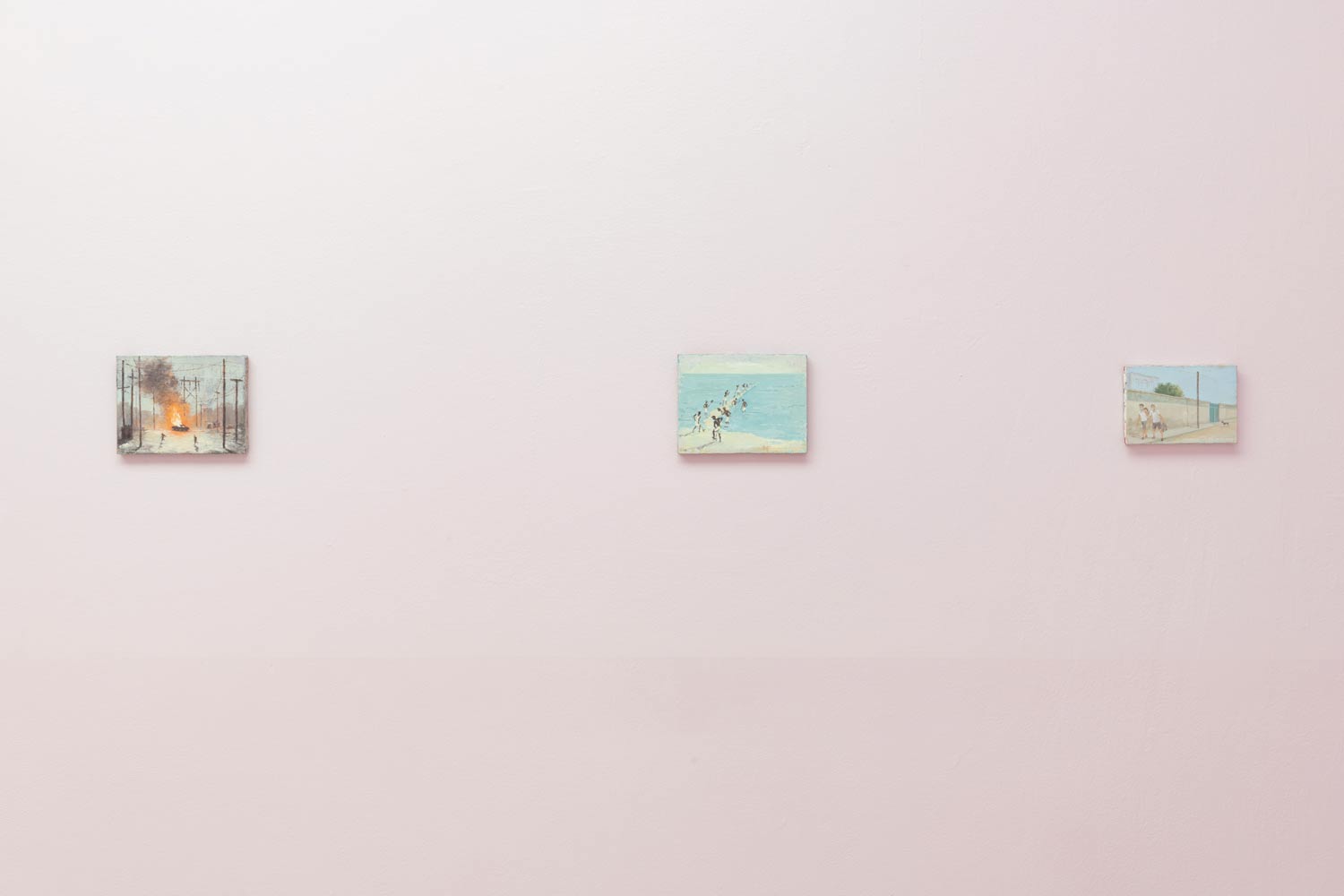

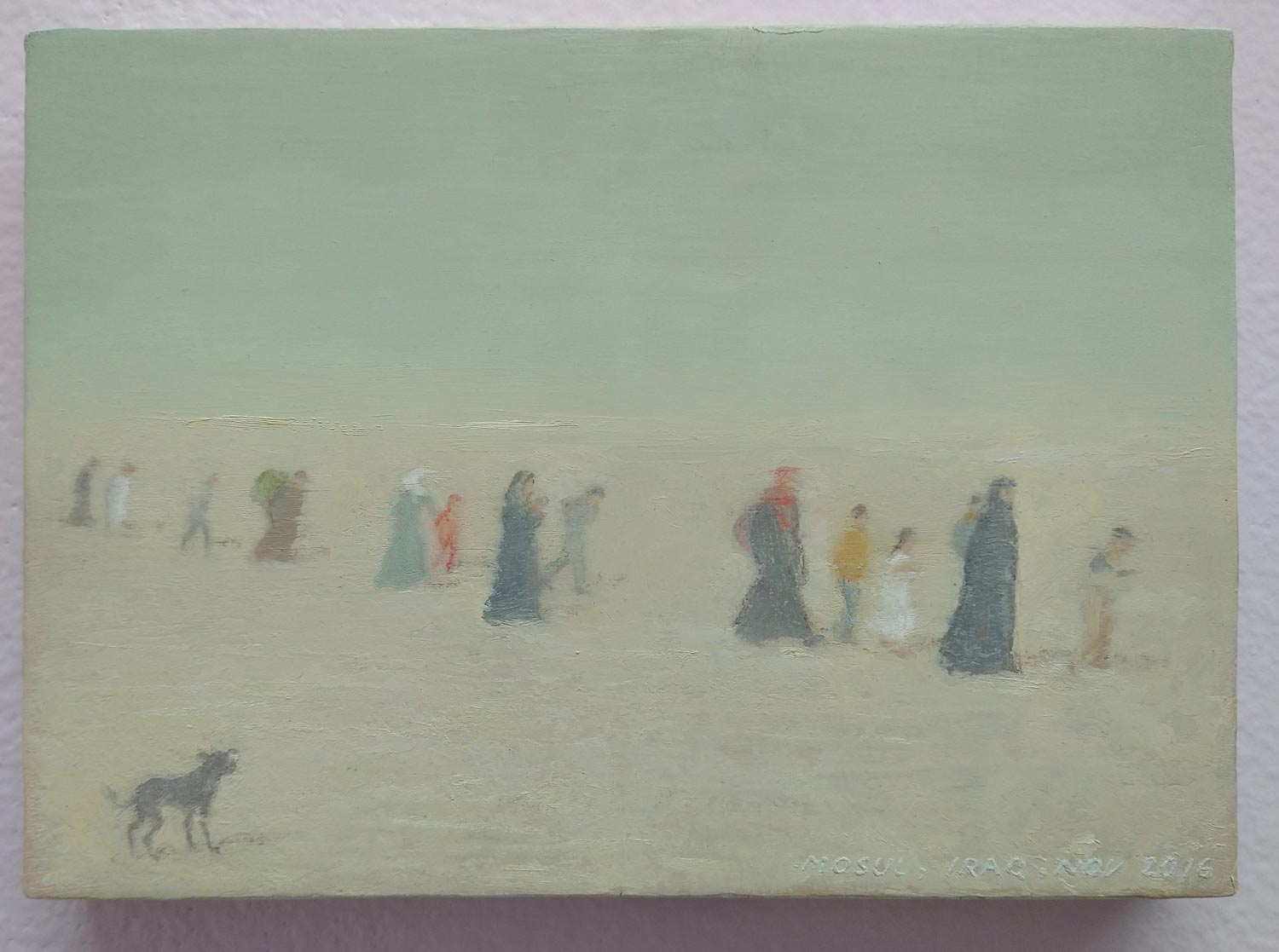

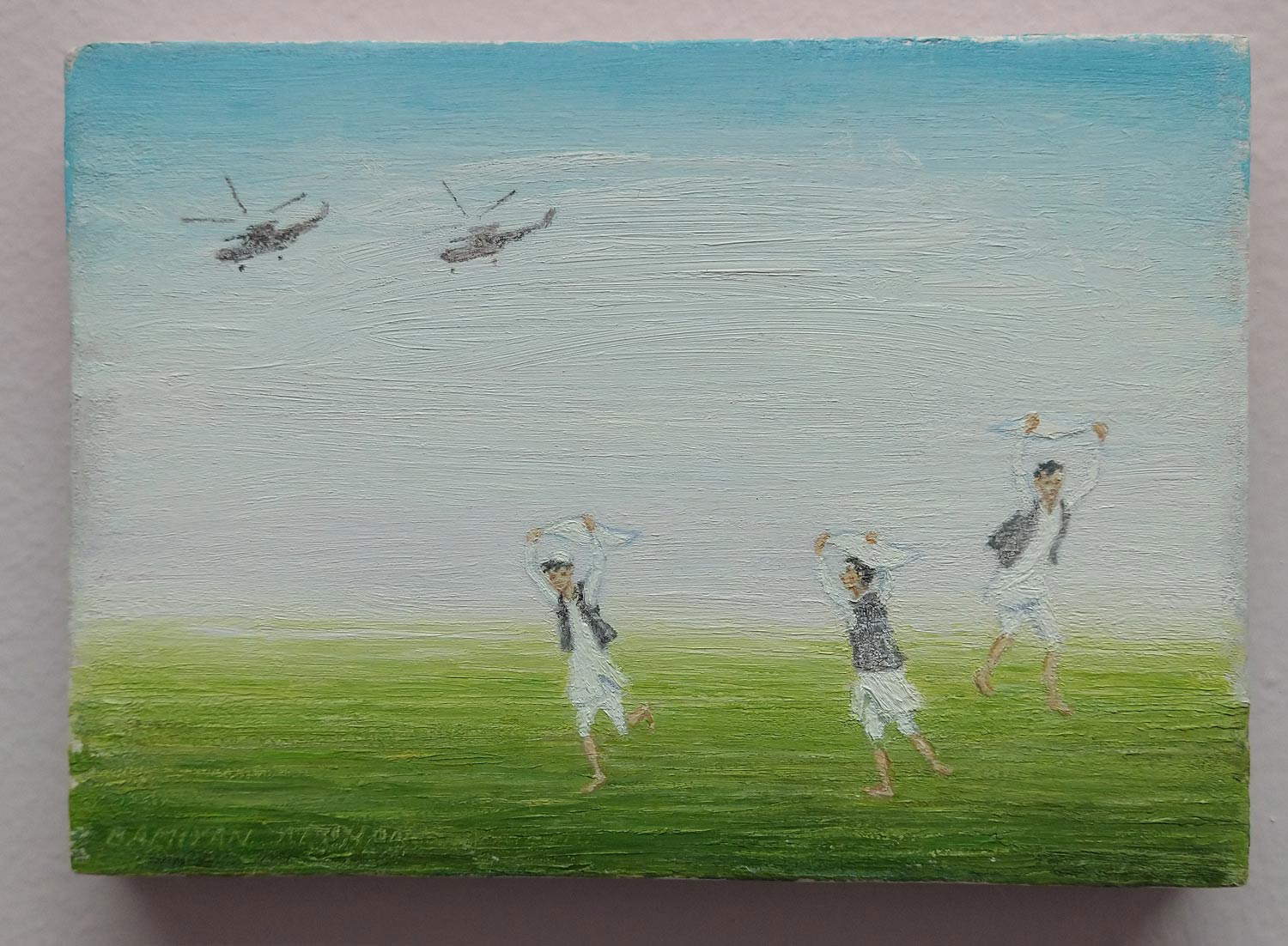

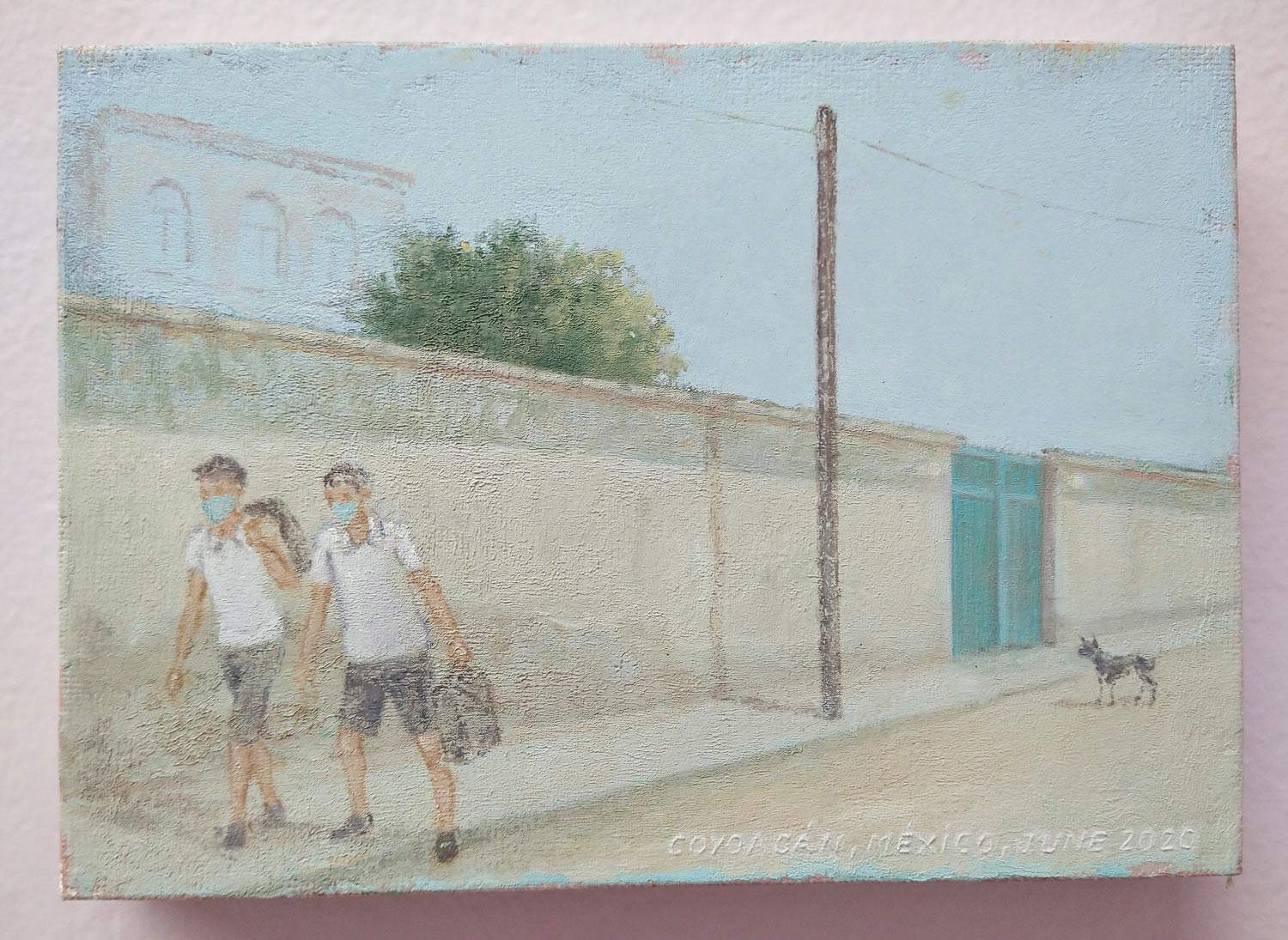

One part of the exhibition displays new and historical videos from Children’s games, while the second section lines up a number of small-format paintings, typical of Alÿs’ production, depicting other children intent on play: for the Antwerp-based artist, the language of painting is necessarily complementary to that of video, since it is capable of revealing readings and meanings that would hardly emerge from filming, and also because, by the artist’s own admission, paintings are capable of bridging that distance that the public often feels towards moving images. The paintings, which Alÿs gives form to at night in his studio, captivate, capture, and surprise with their light poetry and delicate immediacy, and sometimes explore political and social contexts that, by contrast, are never made explicit in videos: so here are children flying kites under war helicopters in Bamiyan, here is a line of mothers with their children and sacks on their backs walking in the desert of Mosul, here is a lonely street in Coyoacán, Mexico, with two little boys wearing surgical masks in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. The paintings, constructed with reduced color ranges (but carefully studied: the color matching seeks to echo exactly the sky and earth tones of the various parts of the world in which Alÿs worked) and with simple, almost elementary forms, hold memories of Brabant Fauvism: the precedents of this painting are to be found in the sketchy but evocative backgrounds of Edgard Tytgat, in the rarefied views of Philibert Cockx, in the synthetic figurines of De Vlaminck, a painter from whom Alÿs however distances himself from the moment when his colors forget the visual overbearingness of those of the Parisian Fauves, but move, if anything, toward the slight tenuity that the Belgian artist will have seen in the works of so many of his fellow countrymen who painted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Then there is the explicit and overt reference to Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Children’s Games, the painting in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, which, first and foremost, becomes the prompter of a method: just as Bruegel wanted to include as many games as possible in his masterpiece, in the same way Alÿs elevates his Children’s games to a universal paradigm. So much so that some games taken up by Alÿs can already be seen in the five-hundred-year-old canvas: the little girls playing with talus on the left edge of the painting are revived in the Nepalese girls playing the same game with stones on a Kathmandu staircase, a group of brats in Bamiyan beat wheels to make them run as Bruegel’s children do in the lower part of the painting, and those in the center jumping the leapfrog are identical to the Iraqi children in Nerkzlia engaged in the same pastime. It could be argued that there is thus a first order of a purely anthropological character underlying Children’s games, which essentially reflects the profoundly humanistic approach that Francis Alÿs has repeatedly demonstrated in his work and which merges with his flâneur attitude: for him, walking through the streets of a city is in itself a performative act, since it is both a “form of resistance,” to use his own words, but it is also an “immediate method of unveiling stories.”

The use of individual stories is also the device Alÿs employs to cloak his works with a political character without turning them into militant works, without the artist turning into an activist. Children’s games videos, although often shot in extremely problematic realities, never have the character of denunciation, nor do they convey the slightest trace of pitiful sympathy. The context remains in the frame: the barracks of a refugee camp in Iraq, the rubble of a street in Mosul, or even the Congo cobalt mine itself, where the problem of child labor is widespread in the very mines from which this valuable material for consumer electronics is extracted. His videos are not even chronicles: they are anecdotes, without a definite beginning or end, that take place in a given place. An idea that brings us back to the myths of antiquity, which for Alÿs are important by virtue of the way they reached their destination, and which implied “an interpretive practice on the part of the public, which had to infer from the work its social meaning and value,” according to Alÿs himself.

Universal and particular thus coexist in a work that goes beyond illustrative intentions (which are not lacking, though) and succeeds in becoming poetry, not least because it often turns on allusive intonations: to Mark Godfrey, author of one of the densest essays on Francis Alÿs, and centered on the relationship between poetics and politics in his work, the stones that some Moroccan children throw on the waters of the Strait of Gibraltar bring to mind the boats that will perhaps one day allow them to cross the sea. A poem that, again according to Godfrey, is based on the concepts of distillation and proliferation, and the very way the exhibition at the Belgium Pavilion is organized is a full demonstration of this: the different means that Alÿs uses to convey to the public the object of his reflections aim at proposing to the public a way of seeing art that is different from the habits; the small or very small format of the paintings complements and anticipates the discourse entrusted to the large canvases on which the videos are projected; the fact that a large number of works are found repeating the same concept over and over again is in apparent contradiction with the minimalism of Alÿs’ aesthetic, as much in the moving images as in the painted ones. Redundancy fortifies the content of Alÿs’ works, minimalism reveals it in its essential elements: this is the aesthetic basis of Alÿs’ works.

Returning to the comparison with Bruegel’s Children’s Games, it is then also necessary to remark on the philosophical basis on which Children’s Games rest. Looking at Bruegel’s painting, one will notice how the Dutch painter’s children do not have childlike faces and bodies: if anything, they resemble little adults. In their “clumsy and convulsive gestures, and on the expressionless faces of these men and women in miniature,” Claudia Farini has written on these pages, “there is no trace of the gladness and serene cheerfulness of childish amusements, and by virtue of such marked disinterest they end up looking rather,” quoting Fritz Grossmann, “like puppets whose actions are not of their own free will.” Bruegel was not interested in depicting the everydayness of his world. Or at least that was not his goal alone: he was not motivated by merely documentary purposes. Play was for him a means of comparing the adults of his world to children occupied only in childish preoccupations. Alÿs seems to reverse this view, however: Hilde Teerlinck recalls that the appeal of play, for Alÿs, lies in the idea that in any context children’s playful activities have universal structures, even when they are ephemeral. Johan Huizinga’sHomo Ludens thus comes to mind: play has a dimension beyond any physical or biological activity. Animals also play, and consequently humans have not added basic characteristics to the idea of play: even the play of beasts presupposes rituality, pretense, fun, rules. Dogs, when they play and bite, know that they must not hurt their opponent, for example. Play for Huizinga shapes culture: “It is through play that society expresses its interpretation of life and the world.” And a true culture “cannot exist in the absence of a certain playful quality, because culture presupposes limitation and self-mastery, the ability not to confuse one’s tendencies with ultimate and higher goals, and rather to understand that these tendencies remain subject to certain limits that are freely accepted. Culture, in a sense, will always be played by certain rules.” Thus play is a most serious activity, and most dangerous for Huizinga is that society in which play is not accorded an important role; dangerous is that human being who takes himself too seriously and abandons all playful perspectives, since this abandonment equals the absence of limits. We also derive this from observing Francis Alÿs’ Children.

At the Belgian Pavilion, nothing goes on stage that we did not already know: The Nature of the Game is, if anything, an acknowledgement of Francis Alÿs, as has always been in the spirit of the Venice Biennale, which has always dedicated rooms, exhibitions and tributes to the great masters, and it is in any case a show consistent with the work of an artist who almost always leaves his subjects open, so that each work is the piece of an indefinite mosaic but clear in its contours. For introducing to the Gardens a work that is certainly not new but so poetic, grounded in those values of valuing lightness and naiveté and the aesthetics of responsibility, as Barry Schwabsky effectively summarized them, that are so typical of his practice and which represent some of the most original work in the world art scene, perhaps Alÿs would have deserved official recognition, for one of the works that most and best marked this edition of the Venice Biennale.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.