by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 01/12/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Carlo Bononi. The Last Dreamer of the Ferrara Workshop' in Ferrara, Palazzo dei Diamanti, October 14, 2017 to January 7, 2018.

There is a particularly apt anecdote to give a measure of the greatness of the genius of Carlo Bononi (Ferrara, c. 1580 - 1632), the great painter to whom Ferrara is dedicating its first monographic exhibition this year, at the Palazzo dei Diamanti. It seems that Guido Reni (Bologna, 1575 - 1642), commissioned to finish a Resurrection left unfinished by Bononi when he passed away, had declined the invitation stating that it would not be possible for him to put his hand to a work by a “non-ordinary” artist, and that he would be “in truth reckless” if he tried to undertake such an undertaking. Now, we do not know whether Guido Reni’s letter, quoted in Girolamo Baruffaldi’s Lives of Ferrara Painters and Sculptors, is authentic (however, there are reasons to believe it is so, according to several scholars), but what is true is that Carlo Bononi enjoyed avery high esteem during his lifetime, and even afterwards. He was a versatile artist, who knew how to juggle between Rhenish softnesses, a naturalism that did not disdain glances at Caravaggio, Venetian atmospheres borrowed from Veronese and Palma il Giovane, a vigorous, strong, warm and deeply felt painting such as masters like Tintoretto or Ludovico Carracci knew how to do, and he was able to achieve surprisingly original results that guaranteed him fame and success: natural that, sooner or later, a monographic exhibition should be dedicated to him.

An exceptional exhibition, starting with the chosen title: Carlo Bononi. Last Dreamer of the Ferrara Workshop. A title that echoes Longhi: it was he, in a 1934 essay, who coined the definition “officina ferrarese” with which the sense of community of Ferrara artists was extolled, their propensity for mutual confrontation, and the choral nature that connoted many of their undertakings, and it was Longhi again who referred to Carlo Bononi as the “last dreamer” of the workshop. The year 1598 was the year of the devolution of Ferrara to the Papal State, the Este court had to move to Modena, and although the artistic environment in Ferrara had not ceased its intense vitality, Bononi had to spend his existence within the confines of a world tinged with a subtle nostalgia and forced to face all the difficulties typical of those far from prosperous times. Difficulties to which, however, Carlo Bononi responded with a painting that “transformed dreams into vital energy” and that “remained a sure antidote to the anxieties of the present” (thus Daniele Benati). It was, in essence, a “declining” world, as Longhi called it, who, to give an idea, made an effective comparison with the literature of Torquato Tasso, a poet a couple of generations older than the painter to whom the exhibition is dedicated. A very successful exhibition, which develops along a chronological line that nevertheless, at times, indulges in interesting thematic variations, which avails itself of the experience of the Fondazione Ferrara Arte and the curatorship of two art historians of great depth and both from Ferrara, Giovanni Sassu and Francesca Cappelletti, and which relies on settings capable of enhancing the works on display (an example, simple but not obvious, because it does not often happen that way: altarpieces are always granted an entire wall) and to often make “incursions” into the context, with continuous references to history, literature, music, and science.

|

| Entrance to the exhibition at Palazzo dei Diamanti. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room of the exhibition. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room from the exhibition. Ph. Credit Dino Buffagni |

|

| A room of the exhibition. Ph. Credit Dino Buffagni |

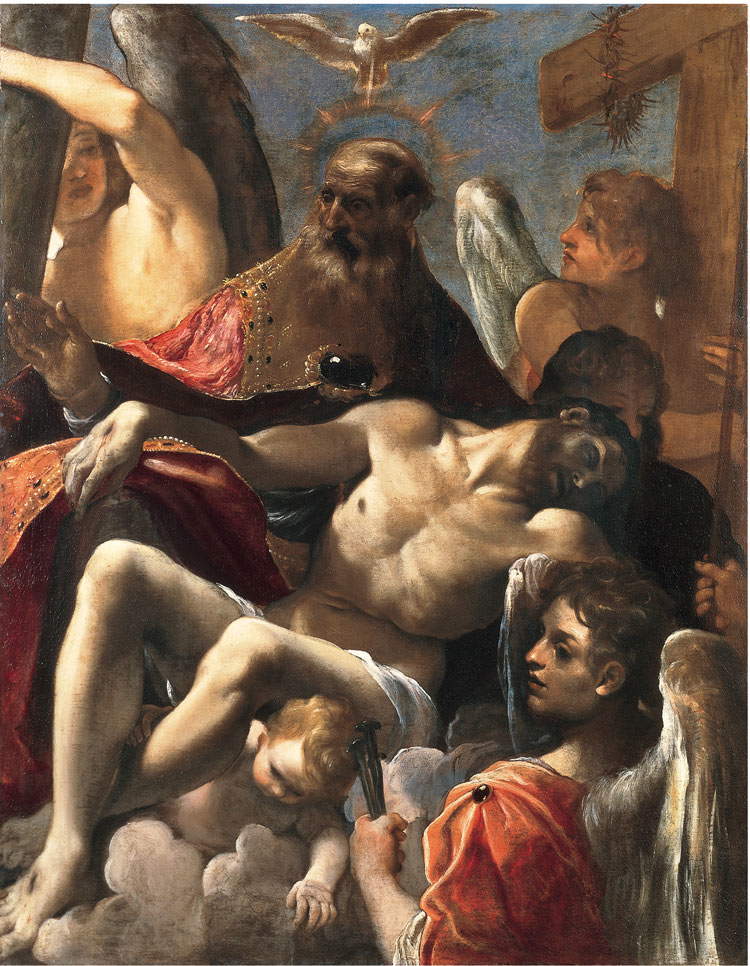

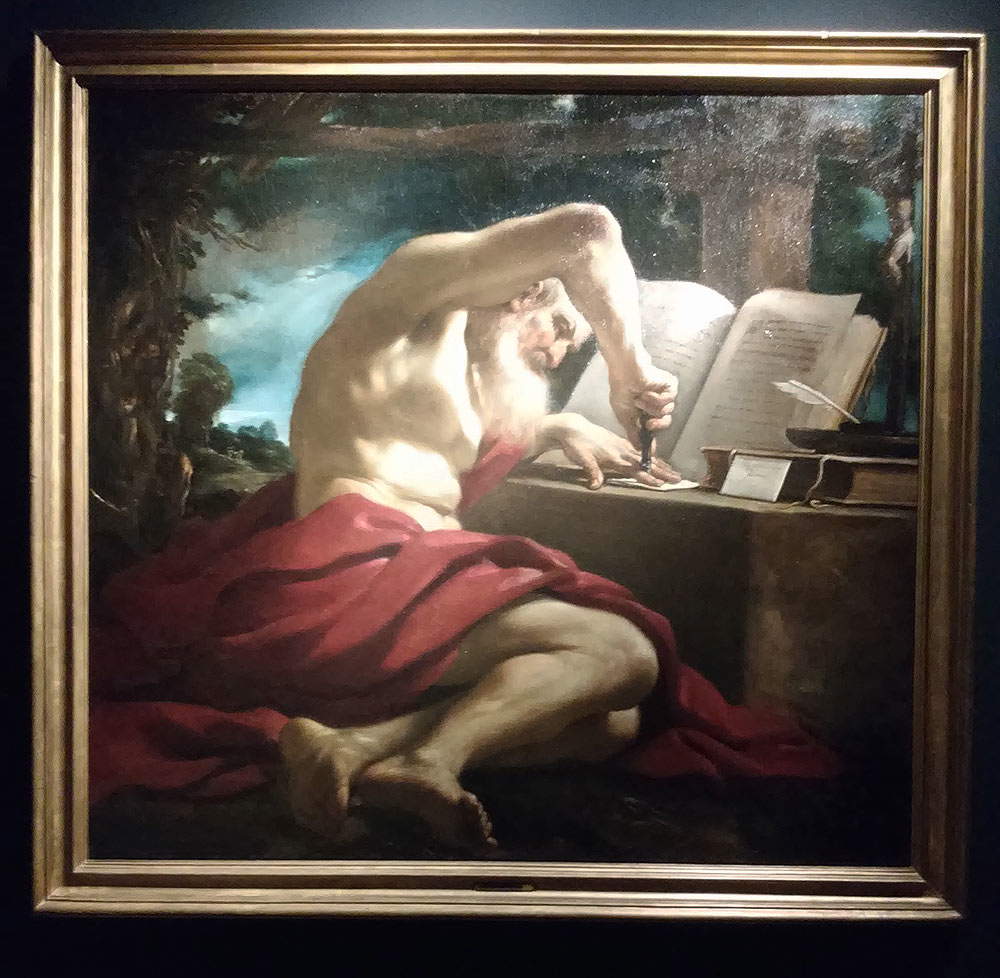

The exhibition starts with an extraordinary comparison between Carlo Bononi, Ludovico Carracci (Bologna, 1555 1619) and Guercino (Cento, 1591 Bologna, 1666). It is worth pointing out how the painter from Cento often looked to Bononi at the beginnings of his own career: an aspect that was also underscored by the exhibition on Guercino held in Piacenza in the spring, where, moreover, that same Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine that we found at Palazzo Farnese at the beginning was on display, while in Ferrara towards the middle. We begin, then, with a prologue aimed mostly at framing Carlo Bononi’s painting in the context of his time: an operation with an eminently popular flavor that responds well to the need to introduce visitors to a painter whose present-day fame among the general public is far from clear. The Pietà, Bononi’s first work that we therefore encounter in the exhibition, is a work completed in 1624: the drama of Caravaggesque taste (Bononi was probably in Rome: We will see this better as the exhibition continues), with the Madonna who, in tears, points out her lifeless son to the observer, is obviously mediated by all the suggestions that the artist had gathered up to that point, starting with those provided by Ludovico Carracci, whose dead Christ appearing in the Trinity provided Bononi with ideas for his Jesus, endowed with a strong physiognomy but tinged with Parmesan languidities. The warm, diffuse light, the setting of the scenes in rural landscapes reminiscent of the countryside around Ferrara, and the marked naturalism are data that, as evidenced by Guercino’s San Girolamo, were to fascinate the young Cento artist in no small measure, who, Baruffaldi recounts again, after seeing Bononi’s works for the first time in Santa Maria in Vado in Ferrara, let himself go weeping with joy.

The prodromes of what the visitor finds in the first room are traced in the room immediately following, entirely devoted to Bononi’s beginnings: the curators, moreover, propose to move his date of birth forward by a decade, to about 1580, according to an idea more consistent with the developments of his art, the first attestations of which date back to the beginning of the 17th century. Among the earliest documented works is the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Maurelius and George, painted between 1602 and 1604 for the headquarters of the Consoli delle Vettovaglie, a Ferrara institution responsible for food matters, and now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna: a work of a devotional character where all the characters (by the way: note the fineness of the group of the Madonna and Child, repeated without variation on the cope of St. Maurelius) are arranged, with their ample volumes mindful of Bastianino’s painting, to occupy every possible corner of the composition (the taste for piled compositions derived from Ludovico Carracci: the same Trinity mentioned above is an example of this) and where the putto in a classical pose, looking instead to Annibale Carracci, holds the model of the city of Ferrara, where the outline of the Castello Estense and the bell tower of the Cathedral can be recognized without particular difficulty. Equally Carracci-esque is a Madonna and Child from the BPER collection, which also reveals clear Venetian influences both in the layout (the Titian reminiscences appear almost immediate, with the column acting as a backdrop and the oblique arrangement of the characters) and in the fullness of the characters and the coloring: one is reminded of Palma il Vecchio, an artist in whom, moreover, the type of the Madonna holding the Child on her knees is rather frequent. Some of the motifs that accompany the visitor in the continuation of the exhibition and in Carlo Bononi’s artisticcareer are instead discernible in the large canvas with Saints Lawrence and Pancrazio from the parish of San Lorenzo in Casumaro, and restored on the occasion of the exhibition: in particular, the tangle of angels appearing to the two saints in adoration anticipates homologous groups, with the difference that, later on, the angels will no longer be soft putti (which here are reminiscent of those Palma the Younger painted in the Glory of St. Julian on the ceiling of the church of San Zulian in Venice, although Bononi resolves the theme with more feeling), but muscular and sensual young men. We see this well already in the next room with the angels of theAnnunciation of Gualtieri, a painting first attributed to Bononi in 1959 by Carlo Volpe, where the still Titianesque setting (the Madonna is identical to that of theAnnunciation now in the National Museum of Capodimonte) is mixed with a domestic intimacy of obvious Baroque taste (Federico Barocci used to scatter baskets with clothes in such scenes: such a presence, in Bononi, manifests itself in the lower right corner) and a delicacy and use of light (clear in the foreground, misty in the background) that instead hark back to Correggio.

|

| Carlo Bononi, Pietà (1621-1624; oil on canvas, 244 x 124.5 cm; Ferrara, Church of the Sacre Stimmate, in temporary storage at the Palazzo Arcivescovile) |

|

| Ludovico Carracci, Trinity with Dead Christ (c. 1592; oil on canvas, 172.5 x 126.5 cm; Rome, Vatican City, Vatican Museums) |

|

| Guercino, Saint Jerome in the act of sealing a letter (c. 1618; oil on canvas, 140.5 x 152 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Madonna and Child Enthroned and Saints Maurelius and George (1602-1604; oil on canvas, 163 x 114 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Madonna and Child (1604; oil on canvas, 66 x 44 cm; BPER Banca Collection) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Saints Lawrence and Pancrazio (1608; oil on canvas, 327 x 220 cm; Casumaro, San Lorenzo) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Annunciation (1611; oil on canvas, 284 x 194 cm; Gualtieri, Santa Maria della Neve) |

Yet, tracing the boundaries of Bononi’s cues is a very difficult matter, since we are talking about an extraordinarily versatile artist, able to renew himself up to the extreme stages of his career, and in this sense the Ferrara exhibition is a continuous surprise that puts the visitor in front of ever new data. Observe, in the fourth room, the altarpiece with Saint Paternian Healing the Blind Silvia, executed for the basilica of San Paterniano in Fano, where the artist probably stayed following a trip to Rome, at the moment not evident from documentary evidence, but conceivable due to stylistic tangencies. Without contacts with Rome, one could not otherwise explain, just by way of example, the figure that appears in the lower right-hand corner of the Fano canvas, a blatant quotation of the figure that, in the Martyrdom of St. Matthew that Merisi painted for the Contarelli chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, appears in the lower left-hand corner. But one could call into question the same Vocation of St. Matthew, with the gesture of the standing figure on the left in Bononi’s work recalling that of Jesus in Caravaggio’s canvas, and even Giovanni Lanfranco, from whom Bononi borrowed “the possibility of rendering Caravaggio’s darkness rich in shades of shadow obtained through colored veils” (so Giovanni Sassu in the catalog). Lanfranco, moreover, is present in the exhibition with one of his best-known works, the Visit of St. Agatha to St. Peter in Prison, effective in offering the viewer an intimist reading of the scene, enhanced by the dramatic use of lights: all elements that provided Carlo Bononi with several opportunities for reflection.

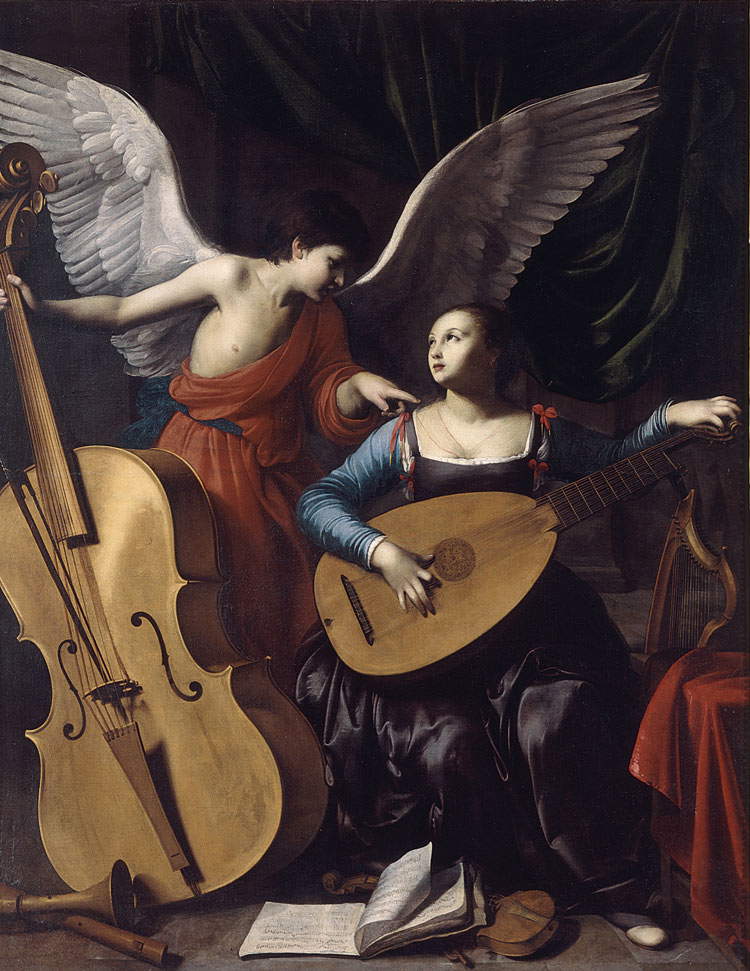

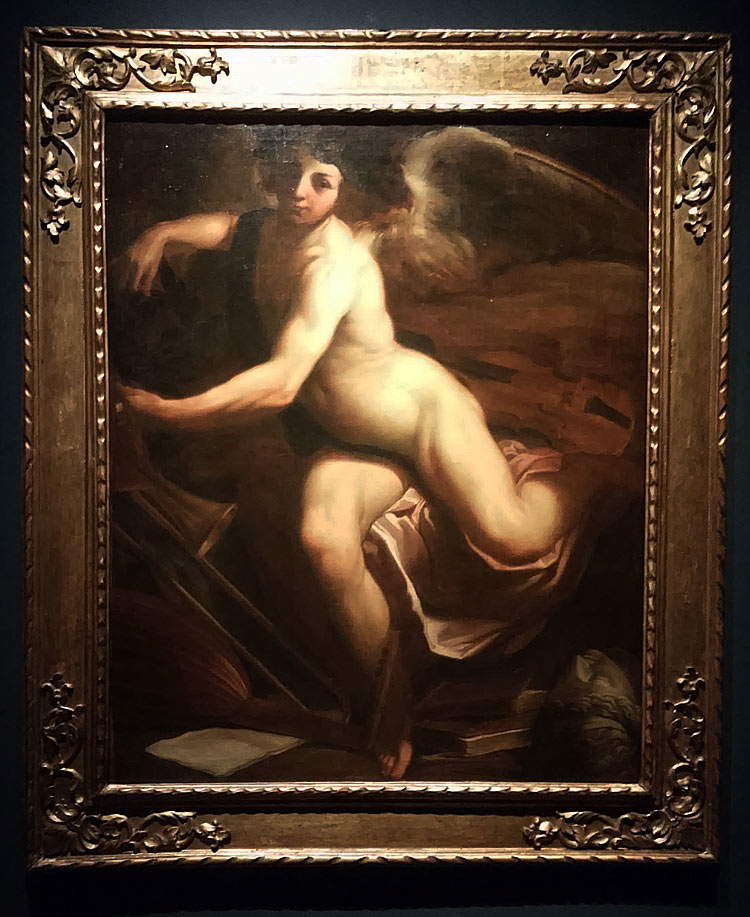

It also makes one of the exhibition’s symbolic works, the Genius of the Arts from the Lauro Collection, think of Caravaggio: a winged young man spreading his wings like the angel of Carlo Saraceni’s Santa Cecilia (featured in the exhibition), denoting an eroticism that is not even too veiled, appearing surrounded by objects related to the arts (a lute, a trombone, a sculpture, a palette, a musical score, books) and shedding his armor (we see it on the right) to symbolize detachment from warlike activities, antithetical to artistic ones. A work datable to the early 1920s, thus after the conceivable Roman sojourn that, in the case, would have to be placed towards the end of the previous decade, it demonstrates clear references to Caravaggio’sAmor vincit omnia, although the catalog records a slight motion of disagreement between the two curators, with Giovanni Sassu speaking of a painting that “evokes well the spirit” of Caravaggio’s masterpiece by “transforming brazen nudity into allusion,” “cleverly rethinking the placement of objects” and “totally reinventing the pose of the protagonist.” the result would be a piece of work “admittedly less blatant but worthy of rivaling in sensuality the other known derivations from the Caravaggesque prototype.” Francesca Cappelletti, on the other hand, speaks in her essay of “two subjects that are actually quite distant.” in quick summary, because Bononi’s references would be to be found in precedents that already existed in Ferrara, because Bononi did not venture to reproduce the pose of Caravaggio’s Love (and like him, for that matter, all the other painters engaged in tackling a similar subject), because of the iconographic distance (one is a genius, the other a cupid), because of the fact that Caravaggio’s protagonist seems to mock the viewer, while that of the Ferrara painter on the contrary intends almost to pay homage to him. That there is in any case a Roman basis is also evident from the comparison with an unpublished work of the same subject, preserved in a private collection and in Ferrara exhibited for the first time to the public, where the reference to Caravaggio appears even more immediate because of the more marked naturalism, which moreover would link this further Genius to the angels of the apsidal basin of Santa Maria del Vado, a watershed enterprise in Bononi’s path (in the exhibition at Palazzo dei Diamanti there are some preparatory drawings).

An entire room, the sixth, is then dedicated to the sensuality of Carlo Bononi’s male nudes, displaying some of the masterpieces in which the Ferrara painter perhaps pours most of his “dreamer” nature. The reader may allow us to define as exciting the comparison between Bononi’s St. Sebastian, executed for the Cathedral of Reggio Emilia at a moment of great professional satisfaction for the artist, and Guido Reni ’s very famous one that is preserved in Genoa’s Palazzo Rosso and that, as Piero Boccardo also reminds us in the catalog entry, invested a very young Mishima with its homoerotic icon charm. As anticipated in the opening, Bononi and Reni knew each other, and there was mutual esteem between the two: natural, then, that there were points of contact. Here they are resolved with two particularly intense masterpieces: the Reggio Emilia painting, harking back to a painting of Caravaggio’s scope, appears nonetheless diluted by Reni’s delicacy, so that the saint reveals all the bursting harmony of his body, minimally scratched by the arrows (and the martyr, with his face, seems to express more stymied disappointment than lacerating pain) and struck full force by the light that brings out the well-turned muscles. That Bononi loved to depict his angels in such muscular and sensual terms is also evident from theGuardian Angel from the church of Sant’Andrea in Ferrara and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, a work in which Carlo Bononi resolves in decidedly sensual terms a very recent iconographic theme, on which therefore the Ferrara painter could exercise all his highly original inventiveness: and here he does so with an imperious guardian angel with an ephebic face but a more than mighty body, who shows an almost intimidated young man the way to follow toward the divine light, while a dark-skinned devil tries, on the contrary, to ensnare him. An angel poses theatrically, aware that beyond the canvas there is someone who is admiring him: and he, of course, certainly does not hide his features, indeed, he flaunts them almost proudly.

|

| Carlo Bononi, Saint Paternian Healing the Blind Silvia (1618-20; oil on canvas, 310 x 220 cm; Fano, Basilica of San Paterniano) |

|

| Giovanni Lanfranco, SantAgata Visited in Prison by Saint Peter and an Angel (c. 1613-1614; oil on canvas, 100 x 132 cm; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, National Gallery) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Genius of the Arts (1621-22; oil on canvas, 120.5 x 101 cm; Lauro Collection) |

|

| Carlo Saraceni, Saint Cecilia and the Angel (c. 1610; oil on canvas, 174 x 138 cm; Rome, National Galleries of Ancient Art, Palazzo Barberini) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Genius of the Arts (c. 1620; oil on canvas, 101 x 82 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Saint Sebastian (1623-24; oil on canvas, 250 x 160 cm; Reggio Emilia, Cathedral) |

|

| Guido Reni, Saint Sebastian (1615-1616; oil on canvas, 127 x 92 cm; Genoa, Strada Nuova Museums, Palazzo Rosso) |

|

| Comparison of Guido Reni and Carlo Bononi |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Guardian Angel (ca. 1625; oil on canvas, 240 x 141 cm; Ferrara, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

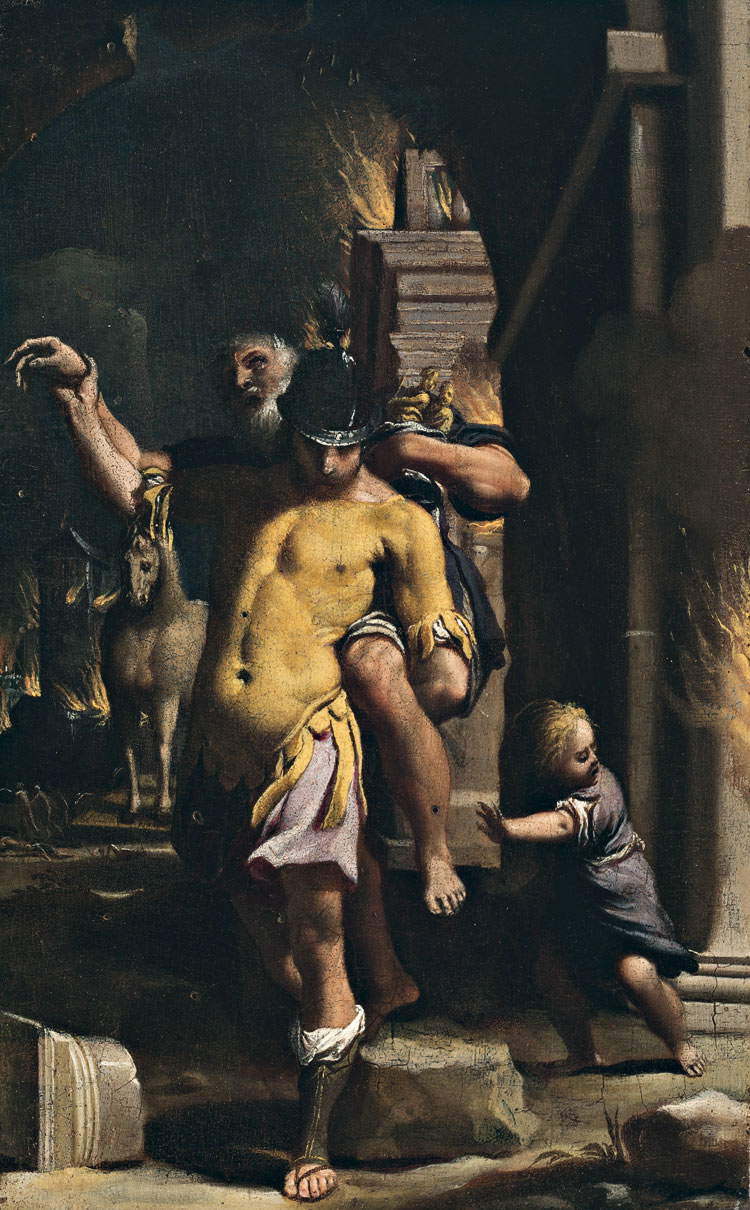

That Bononi retained a certain taste for theatricality is evident even in his small-format works, to which the penultimate room of the Palazzo dei Diamanti exhibition is dedicated. That of easel painting was an area in which Carlo Bononi found himself rivalled by Scarsellino (Ippolito Scarsella, Ferrara, c. 1550 - 1620), an artist who specialized in that genre of paintings, while Bononi instead conquered the “market” of large public canvases, although he also showed considerable skill in small works intended for private devotion. In this sense, one of the most exhilarating proofs is the Noli me tangere, a work probably from his youth, with the scene set in an idyllic garden decorated with a bower: of great effect and delicacy is the detail of the hands brushing against each other; bizarre is the mannerist pose of Jesus, who retracts on the tips of his toes; pregnant with Parmesan-like memories is the figure of Mary Magdalene; vivid are the colors, which are “bright and vibrant, luminous, spread in entire backgrounds that seem to liquefy when, on the crests of the folds, they are lapped by the light” (so Enrico Ghetti in the catalog entry). There is also a moment of direct comparison between the Scarsellino and Carlo Bononi: of the former is exhibited a Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine that presents a recurring subject in the production of the older painter, while of the latter we find an Escape of Aeneas from Troy (kept in the same collection as Scarsellino’s work) where, although in a small space, Bononi succeeds in creating a scene characterized by a strong narrative flavor, with the Trojan Horse (thus the cause of the flight) in the background, the flames of the fires raging throughout the city, Aeneas carrying his exhausted old father Anchises on his shoulders (note the hands of father and son on the left edge), and little Ascanius running scared.

All large works, on the other hand, are on display in the last room, where the visitor will find Carlo Bononi’s latest achievements, all of a sacred nature. Here, the interesting fact is the sensibility in advance of the Baroque that distinguishes certain realizations, starting with the so-called Pala Estense where the oblique arrangement of the characters that is still not oblivious to Titian’s Pesaro altarpiece, with the Holy Family raised on the large plinth that occupies half the composition, is made modern by their attitudes and theatricality: St. Barbara’s gestures, beautiful with her more than realistic face, and St. Joseph’s hand totally exposed to the light and skillfully placed beyond the architecture, soaring above the cloud that furrows the sky in the background, are of particular effect. Also naturalistic, complex and exciting is the Saint Margaret Enthroned with Saints Francis, John the Evangelist and Lucy: the scene opens high with angels seated on fluffy clouds to let the divine light swoop over the protagonists, rendered again with exceptional realism (note the Saint Lucy, with pearly complexion and all-Nordic beauty) and arranged in a pattern that accentuates the movement that animates the whole scene. And still strong proto-Baroque accents demonstrate theApparition of Our Lady of Loreto to Saints John the Evangelist, James the Greater, Bartholomew and Sebastian (St. Sebastian has only re-emerged after a restoration of which the catalog gives a timely account), with Our Lady making her way through the clouds while the saints seem evidently surprised at such an epiphany, with St. James even turning his back peeking behind him rather than coming forward like St. Bartholomew, at the center of the scene. And the protagonist is still that sky made of large gray and dark blue clouds that represents perhaps the one constant throughout Bononi’s work.

|

| Carlo Bononi, Noli me tangere (c. 1608-1614; oil on canvas, 69 x 91 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Scarsellino, Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (c. 1610-1612; oil on panel, 37.5 x 26.5; Grimaldi Fava Collection) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Aeneas Flees from Burning Troy with Anchises and Ascanius (1615-18; oil on panel, 32 x 20 cm; Grimaldi Fava Collection) |

|

| A comparison between the Scarsellino and Carlo Bononi |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Holy Family with Saints Barbara, Lucy and Catherine (Pala Estense) (1626; oil on canvas, 261 x 161 cm; Modena, Galleria Estense) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Saint Margaret Enthroned and Saints Francis, John the Evangelist and Lucy (1627; oil on canvas, 303 x 185 cm; Reggio Emilia, Museo Diocesano) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Apparition of Our Lady of Loreto to Saints John the Evangelist, James the Greater, Bartholomew and Sebastian (c. 1622-1623; oil on canvas, 259 x 170 cm; Toulouse, Musée des Augustins) |

The final viaticum of the exhibition is a pocket map illustrating all the places in the city (churches, museums, historic buildings: a visit to Santa Maria in Vado, a few hundred meters away from Palazzo dei Diamanti, is essential) where works by Carlo Bononi and all the great protagonists of that season can be found: Carlo Bononi. The last dreamer of the Ferrara workshop certainly does not hide its nature as an exhibition intimately linked to the territory. It should be emphasized that the exhibition, beyond the unquestionable merits of a scientific project of remarkable philological rigor, is also distinguished by an effective communication apparatus that, also through the use of web and social channels, has aroused great public interest in the art of Carlo Bononi, resulting in feedback that, for an exhibition of this kind, seems extremely flattering. Among the positive notes was also the didactic apparatus, which was very effective in synthesizing stylistic particularities and comparisons for the benefit of the visitors: the panels in the rooms offer an overall picture that takes into account almost all the works that the visitor finds in each room, there is no lack of in-depth information dedicated to the historical and cultural context, and worthy of consideration is the idea of making the curator’s narrative available to the public, free of charge, on the web. A dynamic narrative, which literally accompanies the visitor along the rooms, and without in-depth insights unconnected to each other as happens in almost all audioguides, but with a linear narrative that invites to dwell on the details, to discover unusual details, to admire the works not as individual isolated manifestations, but as texts in dialogue with each other.

As for the important catalog, a compendium of all the most up-to-date information on the artist, it is worth mentioning, among the contributions that are not to be missed, Giovanni Sassu’s introduction, Francesca Cappelletti’s essay on the “Roman connections” of Carlo Bononi’s art, Cecilia Valentini’s essay on small-format paintings, Lara Scanu’s concise but very particular contribution on travelers’ comments about Bononi’s art, and Michele Danieli’s essay on the artist’s graphic activity. Also noteworthy are a small collection of three essays written by as many eminent scholars who “loved” Bononi (Andrea Emiliani, Erich Schleier and Daniele Benati) and who recount him from a personal, almost intimate point of view, and Giovanni Sassu’s paths that, among the entries, frame the various moments of the great Ferrara painter’s artistic journey with formidable clarity.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.