Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi: two names that, if placed at the head of the title of any exhibition review, would probably suffice alone to guarantee its success. And so it would seem to be for Caravaggio and Artemisia. The Challenge of Judith, the exhibition set up in the ground-floor rooms of Palazzo Barberini in Rome until March 27, 2022, and which has already met with wide public approval. With the title removed, the exhibition curated by Maria Cristina Terzaghi is essentially dedicated to the iconographic fortune of Michelangelo Merisi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, one of the most famous paintings in the Palazzo Barberini collection, perhaps second only to Raphael’s Fornarina. The wide dissemination that images of Judith experienced at least from the 1680s onward is an eminently political fact: in 1545, the third session of the Council of Trent established the inclusion of the book of Judith in the biblical canon, "in blatant contrast to Luther’s choice (1531) to include it among the Apocrypha of the Bible he had translated," wrote Luciana Borsetto, who on the theme of Judith between Renaissance and Baroque curated a conference held in Padua in 2007. It was a matter of affirming the symbolic role of a myth that could be schematized in two moments, that of the threat (of Holofernes to the Jewish people) and that of salvation (the end of the story), in an era that saw the Catholic Church really threatened by internal and external enemies: in such a framework, Judith became vivid, eloquent and triumphant allegory of the Counter-Reformation Church. The inclusion, between the 1980s and the 1990s, of the book of Judith in the Sisto-Clementine Vulgate (the Vulgate, it will be worth remembering, was the only version of the Bible allowed by Catholic authorities, so much so that all vernacular translations would be included, in 1596, in the Clementine index), was the episode that promoted the myth’s notoriety.

The main novelty of the exhibition, more than the in-depth study of the theme itself, on which other exhibition occasions had already intervened although obviously without reaching the degree of verticality of the Palazzo Barberini review (most recently, one could mention the exhibition on Artemisia Gentileschi at Palazzo Braschi held between 2016 and 2017, where there were fourteen Judiths), it is the monographic cut, the focus on the single theme that allowed for the gathering of great masterpieces and lesser-known works, the unique possibility of seeing so many works having the same subject brought together in one place, and thus the possibility of ascertaining with direct comparisons the scope of Caravaggesque’s word. In an itinerary marked along four sections (the precedents of the late sixteenth century, Caravaggio’s Judith and its interpreters, Artemisia’s Judith, and the comparison with the iconography of David and Salome), particular emphasis is given, right from the introduction published in the catalog, to the Judith, which Artemisia painted with Merisi’s precedent in mind, defined by curator Terzaghi as a work that “goes beyond” Caravaggio and becomes “the scene of an almost total identification,” a painting to which to assign “the golden palm of interpretation of Caravaggio’s masterpiece.”

The attempt to assign the “palm” in the competition to those who have best revisited the Judith painted for Ottavio Costa partly explains the fact that the figure of Artemisia is found to tower over the other artists, to the point of having a dedicated section, since this primacy is recognized by the curator on the basis of the “pathos” that Artemisia would have been able to instill in the characters, a pathos obtained also because of her own experience: from the formal level, the outline of the exhibition thus deviates to the psychological one (it is impossible to read Artemisia’s Judith Beheading Holofernes without referring to her personal history, a situation that, however, does not make the painting a hapax, if read as a figurative text dropped within a precise context) and then resumes its path in the final section, with a clear oscillation in the definition of the exhibition’s identity. However, already on the occasion of the major exhibition on Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in 2001, Judith Mann warned of the difficulty of arriving at a definitive reading of the image of the Capodimonte painting later replicated in the Uffizi variant, not least because we do not know the circumstances under which it was born, nor has a certain dating yet been found, and consequently the painting has been variously interpreted either as a more or less direct response to the violence suffered by the artist in 1611 (Terzaghi herself in the catalog: “a work where emotion builds the painting itself” and where one can read “the desperate force of rebellion against honor betrayed”), or as the reflection of a psychological elaboration of the sad affair (Griselda Pollock: “the myth is the blank screen on which the text or image etches a particular complex of meanings informed by the exchange between the artist’s projections and the possibilities of misrecognition and projection offered by the myth itself”), not to mention those who have downplayed references to personal experience (Beverly Louise Brown: “her starting point was much more visual than psychological”). Although therefore oriented toward a precise direction, the reading of the painting does not disregard framing it in the artistic context of the time, which is well reconstructed by the Palazzo Barberini exhibition.

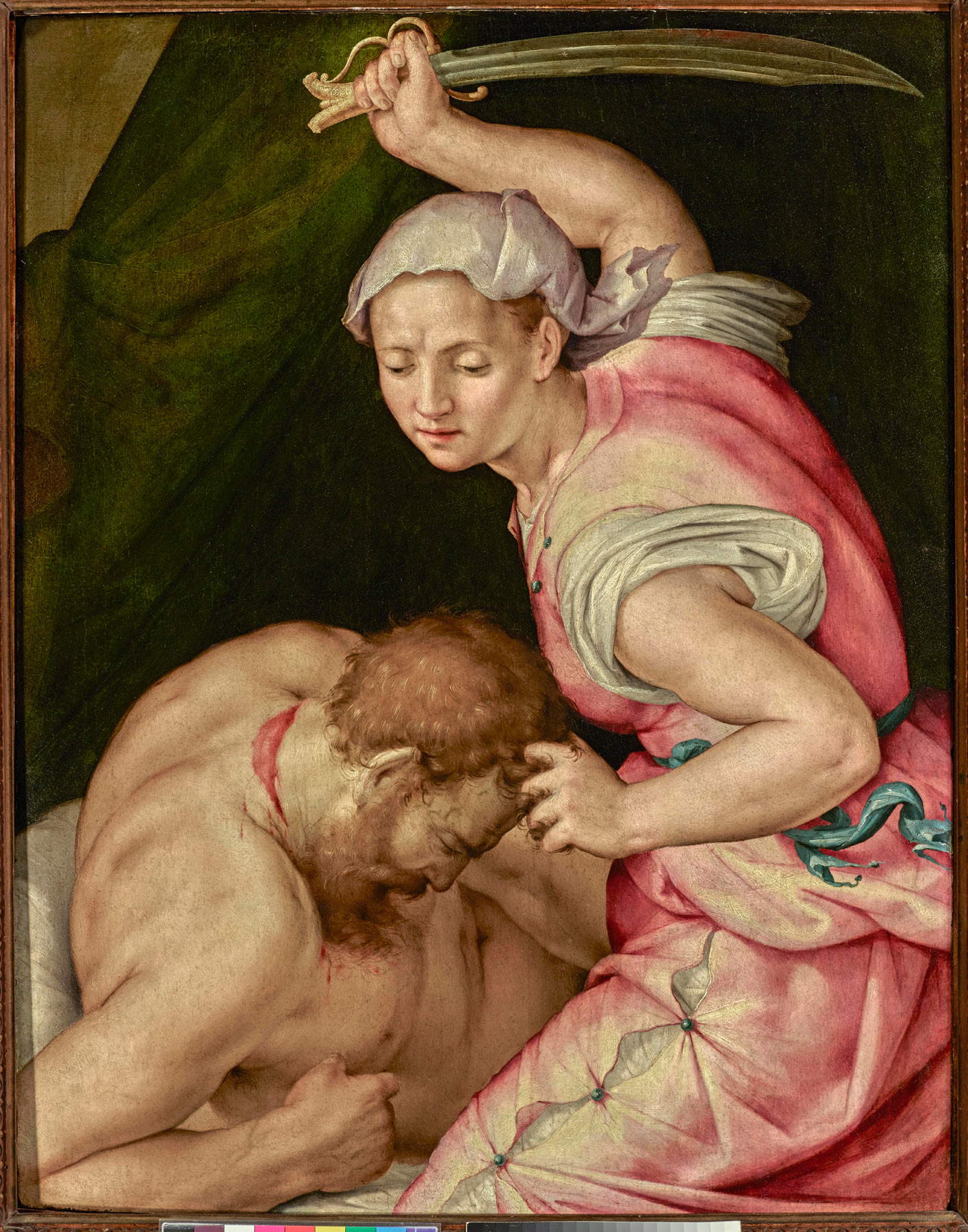

The reconstruction starts off immediately with an interesting novelty, an unpublished work by Pierfrancesco Foschi from the 1640s that rereads Donatello’s Florentine Judith and the inebriated Noah from the Sistine Chapel to result in an image of great violence and rawness, with Judith caught in the act of raging, raising her scimitar, on the head of Holofernes, who, as indicated by the deep and bloody wound at the base of the nape of the neck, has already received a few blows and is about to be severed cleanly from the rest of the body. This is proof that the novelty of the Caravaggesque text is not to be found in its violence. And from the sixteenth century also comes the demonstration that Artemisia is not the only woman to display ferocity: on loan from Parma comes Lavinia Fontana’s famous Judith, who holds in her hands the head of Holofernes, still dripping with blood, and casts a last glance at the Assyrian general’s body (the splatter detail of the severed neck is not concealed by the Emilian painter) while handing the severed head to the servant Abra, in an excess of theatricality that anticipates certain paintings of the following century (we are, however, chronologically close: the Bolognese’s image is from 1595). It is, however, a very different theater from the seventeenth-century one: there is still, in these paintings, a fully sixteenth-century refinement in gestures and poses, there is an analytical and almost maniacal attention to every single detail, as is also evident from Tintoretto’s Judith on loan from the Prado, a work of skilful and highly calibrated direction.

The next room, the most scenic of the Palazzo Barberini exhibition, places at its center Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, whose role as a fundamental pivot point for the art of the time is reiterated. The extraordinary novelty of the painting was effectively summarized by Michele Cuppone, who has recently devoted several writings to Judith, in the catalog of the aforementioned exhibition at Palazzo Braschi: “never until that moment had such a level of crude realism been achieved, where the painter’s deepest intent seems to be to impress the observer, lowered into a theatrical dimension.” Caravaggio chooses a moment in the story that had very few precedents, that in which Judith hurls herself at Holofernes, and above all he chooses to depict it with a naturalism unprecedented for the biblical episode. It is a painting on which many words have been spent, even recently: Terzaghi, on the occasion of Caravaggio and Artemisia, returns in particular to two topics in the long essay devoted to the work and its early interpreters. The first is the dating, fixed at about 1600 despite the knowledge of a down payment, dated 1602, from the commissioner Ottavio Costa to Caravaggio for an unspecified “painting,” and since the banker’s will lists only two other Caravaggio paintings he owned, one would have to admit (discarding the St. Francis of Hartford, a painting recognized by all as a juvenile) that the note should be referred to the Kansas City St. John the Baptist, imagining an advance of at least a couple of years for a painting, the one now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum, intended for an oratory in Albenga whose decoration was not begun until late 1603. The second is the identification with Fillide Melandroni, a long-standing suggestion (dating back to Roberto Longhi), already proposed by the scholar in the past, moreover, and revived here, since the Judith is related to the lost Portrait of Fillide, the Saint Catherine of the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and the Magdalene of the painting with Martha and Magdalene in Detroit, all women who show the same physiognomy, and to whom, moreover, should be added the Virgin of the Nativity already in the Oratory of San Lorenzo (whose dating to the Roman years is now widely accepted), which indeed is, in all of Caravaggio’s production, the female figure most closely resembling Ottavio Costa’s Judith. “The high forehead, thin eyebrows, large dark eyes, hair parted with curls sticking out or styled in the fashion of the high topknot,” and pearl drop earrings are details that, according to the curator, tie these images together.

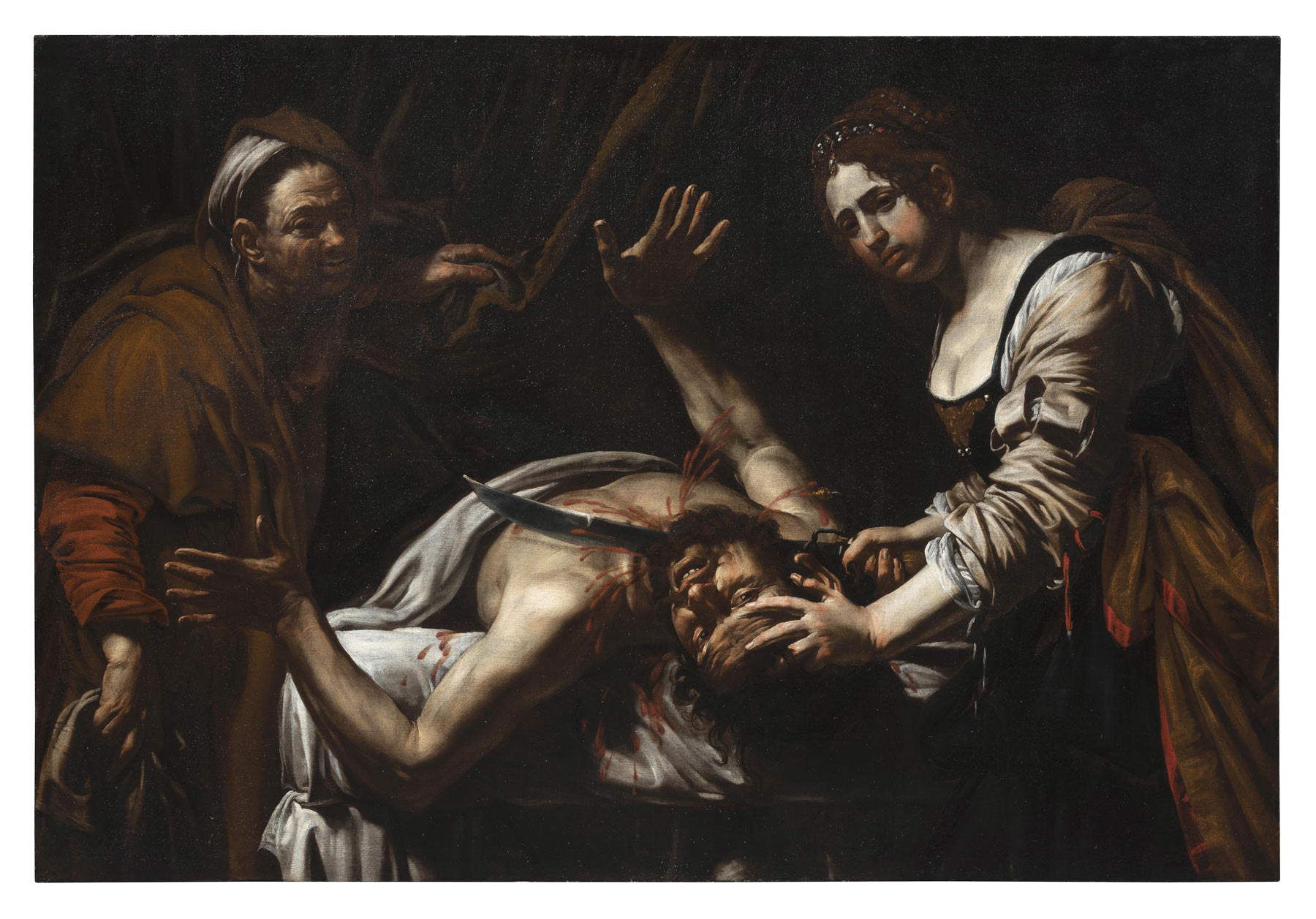

Ottavio Costa was very jealous of Caravaggio’s painting and rarely showed it, lest too many copies would lead to its devaluation. Terzaghi speculates that one of the rare exhibitions of the work took place on the occasion of the marriage of Luisa Costa, daughter of the banker, and Pietro Enriquez de Herrera, son of Ottavio’s partner, in 1614, but it is almost certain, the curator argues, that someone must have seen it much earlier, since early works whose derivation from the Caravaggio prototype is indisputable are known. Among the artists who were immediately fascinated by Caravaggio’s text are those on display in the exhibition immediately next to the Palazzo Barberini’s Judith: these are the paintings by Giuseppe Vermiglio (left, from the Klesch Collection in London) and Louis Finson (right, from the Intesa Sanpaolo Collection: about the painting’s autography, however, there is no certainty). The Lombard’s painting is particularly interesting because it was recently discovered (it was published in 2001), because it is very rarely seen exhibited, because it is not the slavish translation of an imitator but is a painting that stands out for its characters of originality, and because the figure of Vermiglio, an artist who was among the first to spread Caravaggesque novelties in Lombardy, is an artist whose physiognomy is still being reconstructed. Finson, who was present in Rome in the early seventeenth century, according to Terzaghi was perhaps able to see the Judith in Caravaggio’s atelier while the painting was in progress, and Vermiglio, writes Chiara Dominioni, “may have had occasion to see Merisi’s work thanks to the circle of acquaintances that linked him for some commissions to Duke Giovanni Angelo Altemps, a client of the Banco Herrera & Costa and buyer, in those years, of copies of Caravaggio paintings sold by Prospero Orsi.” Definitely later, but no less interesting (on the contrary) are other variations on the theme: Valentin de Boulogne’s dark gloom in the canvas arriving from the MUŻA of Valletta in Malta, Bartolomeo Mendozzi’s gory reinterpretation (a name recently assigned to the “Master of the Incredulity of St. Thomas” to whom the painting was referred), the candlelight of Trophime Bigot’s cold and celebrated painting arriving from the Pilotta in Parma, and Filippo Vitali’s decomposed Holofernes, the most recent of the paintings lined up in this room that displays some of the highest interpretations of Ottavio Costa’s Judith.

Separate space, as anticipated, was given to Artemisia’s Judith for the reasons mentioned above. Artemisia was among the first to reread Caravaggio’s Judith, although her debts range beyond and have long been pointed out by critics: it is difficult not to relate the painting to Rubens’ “Great Judith” known today only from an engraving by Cornelis Galle (a work, that of Rubens, whose echo was probably second only to Caravaggio’s: it will be worthwhile to give here an account of a work probably of the Veronese school, comparable perhaps to the manner of Felice Brusasorci, which emerged on the market at the end of 2020, passed at auction by Finarte and generically assigned to a painter from northern Italy but with openings on Claudio Ridolfi, who seems to have a close relationship with the Rubensian Judith), just as it is highly likely that the idea of the recumbent Holofernes derives from Orazio Gentileschi’s David now in Dublin, and further dependency relationships could link the painting to Adam Elsheimer’s Judith, cited in the catalog as one of the very first (“hot”) impressions of Ottavio Costa’s Judith. Here, too, the curator returns to the issue of dating, which had been postponed to 1617 (as opposed to the more traditional date of 1612) by Francesca Baldassarri, on the basis of a July 31, 1617 payment paid in Florence by the noblewoman Laura Corsini to the painter for a “Judith” that the scholar proposed to identify with the one now in Capodimonte: the earlier date is reaffirmed in the exhibition substantially on the basis of two main clues, Marcantonio Bassetti’s drawing taken from the painting of Judith and preserved in Verona at the Museo di Castelvecchio (the painting is complicated, however, by the fact that Bassetti stayed in Rome until 1620, and to 1620, according to Baldassarri, could be dated the Florentine version of Judith, which may also have been produced in Rome), and the painting attributed, on the occasion of the exhibition, to Biagio Manzoni by Giuseppe Porzio, which appears to take up Artemisia’s Judith in a direct way. Until before the exhibition it was given to Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri (who published it, as a painting by the Marche artist, had been Andrea Emiliani in 1988, who moreover confidently dated it to a period between 1615 and 1618), and this change of attribution is one of the major and most interesting novelties of the exhibition: to make this work a diriment argument in the question of dating Gentileschi’s Judith to 1612 would require firstly accepting the attribution to Manzoni, secondly confirming the hypothesis, launched by Andrea Bertozzi in 2014, of the identification between Biagio Manzoni and the “Biagio painter garzone” recorded in the states of souls of two Roman parishes between 1614 and 1617, and finally admitting that after 1617 Manzoni immediately returned to his native Romagna. However, there are still documentary gaps in Manzoni’s biography that are too wide to consider the case closed.

In any case, to return to the issues that most fascinate the general public, what emerges strongly from the third section of the exhibition, rather than an alleged primacy of Artemisia, is, if anything, the evidence of a large number of artists who tried to mediate between Caravaggio and Rubens: Artemisia herself, to whom are added Giovanni Baglione, author of a Judith that takes up the profile of Caravaggio’s Abra (in addition to the intonation “intended as merely epidermic and typological,” writes Michele Nicolaci in the catalog) but who in the composition had to keep in mind the Rubensian precedent, and then again Pietro Novelli, present with his Judith in the next room (in which, however, the third section continues).

The plot of the exhibition is then enriched with the natural confrontation between father and daughter that comes alive in the direct comparison between Judith and the fantesca with the head of Holofernes of Oslo, a work by Orazio Gentileschi from 1608-1609 that constitutes the most obvious precedent of one of the details on which the readings of the Capodimonte Judith dwell most (namely, the fact that it is one of the first times in which Judith and Abra appear as peers: the theme of “female solidarity” on which some readings insist thus finds an anticipation in Horace’s complicity of the two women, which is in any case a topos in the iconographic tradition of Judith, and it is, if anything, the servant girl’s dismay that is a new fact). Horace was certainly familiar with Caravaggio’s painting, being the artist in the exhibition who had the closest relationship with Merisi, but he remains impermeable to it: there is no trace in his production of the savagery that appealed to his contemporaries. There is, however, vivid tension in Hartford’s splendid painting, the best painting in the section, which captures an apprehensive Abra as she looks around circumspectly, fearful of being discovered as she carries away the head of Holofernes: there is no cruelty (the severed head itself seems to be made of wax, Patrizia Cavazzini suggests), there is not even the penetrating realism of Caravaggio, but there is a drama in full swing. Again, we continue with some welcome reflections of Guido Cagnacci in the Judith of the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, until we arrive at the painting by Johann Liss, one of the most original in the exhibition, a very studied and calibrated invention, Mannerist in taste, but whose realism is reminiscent of what the German artist had seen in Rome in the 1920s. Finally, the itinerary closes with the fourth section, the most evanescent, since it falls to it the not easy task of comparing the iconographies of Judith, Salome and David in an excessively confined space: the complicated objective is solved in just five paintings that thus provide only a few cues. However, the final sharpness of Valentin de Boulogne’s David and Judith, on loan from the Thyssen-Bornemisza and the Musée des Augustins in Bologna, respectively, should be highlighted to stage a leave-taking of the highest order with the purpose of suggesting to the visitor how often, at the time, paintings with Judith and David were commissioned as pendants: this is not the case with Valentin’s two paintings, which were born in different contexts and separated by a decade, but the expedient of displaying the two paintings side by side conveys the idea well.

The exhibition at Palazzo Barberini, even with the reservations mentioned above, must also be credited with having created, in a sober setting and with lighting close to perfection, an itinerary of strong hold and considerable impact, and with having condensed numerous solicitations into an itinerary of just twenty-nine works. No mention was made above of other cues that provide new material for scholars to debate: for example, Giulia Silvia Ghia, for the painting of an unknown Flemish in a private collection moves, with great caution, the name of Abraham Janssen. Again, Alessandra Cosmi accepts an invitation from Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari dating back to the Orazio Gentileschi exhibition in Fabriano two years ago and further investigates a David with the head of Goliath by Girolamo Buratti. Then there is the discovery, to which a short essay in the catalog is devoted, by Francesco Spina who publishes an unpublished payment note that can provide further confirmation of the familiarity between Caravaggio and Louis Finson. For the experts, in short, there is much to discuss.

The general public, on the other hand, amid enthusiastic comments released on social media, has been crowning the exhibition since its first days of opening. If the exhibition is to be seen as a narrative, albeit with a few hiccups (to know the premise, for example, the catalog is indispensable: from the panels alone, it might escape the reason for the spread of paintings dedicated to the story of Judith) the narrative proceeds expeditiously, enjoyably and pressing. There is the anniversary, that is, the 70th anniversary of the discovery of Caravaggio’s Judith by Roberto Longhi, and thus there is the basis for the narrative (which precisely from the events of 1951 begins). There are masterpieces, there are Caravaggio and Artemisia, there is the theater of reality. And there is an exhibition that comforts what the audience expects. Satisfaction guaranteed.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.