Vittorio Sgarbi has not changed one iota the formula of the “exhibition in disguise” (so we could call it, taking up a definition that, moreover, is his), proposed for the second year in a row to the public of Lucca. Last year with an exhibition, successful and high-profile, on Pietro Paolini, masquerading as a review on Caravaggio (it should be added, for the sake of the record, that it had been the exhibition from which the Rutilio Manetti case, still on the verge of being resolved, which held court in the pages of the political chronicle between last December and the beginning of this year, would have started). This year, however, comes to the Cavallerizza an in-depth study of Lucchese neoclassicism disguised as an exhibition on Canova. It is imposed, one will say, by the peremptory and unappealable reasons of marketing. Who would travel from outside Lucca to see an exhibition on Pietro Paolini? An artist of undisputed caliber and among the Caravaggesque painters of the first hour, certainly, but of whom people are already beginning to lose memory past Montecatini, or perhaps even before. Better then to make the public believe that there will be an exhibition on Caravaggio at the Cavallerizza, even if Merisi’s presence is limited to a reproduction and two paintings that have never found, and never will find, unanimous critical acclaim. This year’s exhibition, Antonio Canova and Neoclassicism in Lucca, exploits the same mechanism, in perhaps an even more blatant manner, leading visitors to believe that they are visiting a major exhibition devoted to Canova, with an appendix on Neoclassicism in Lucca. True, we have more Canova this year than Caravaggio a year ago. But those who expect a focus on the Venetian sculptor, who imagine to find in Lucca marbles here convened from all corners of the globe, will perhaps come out disappointed. And that’s probably just as well: there was no need for another exhibition on Canova. The usual, bullish, repetitive exhibition on Canova. Sgarbi has rightly chosen to investigate the origins and development of neoclassicism in the land of Lucca, an area that proved extremely receptive to the ideas of Canova, who is present in the exhibition above all as a numinous presence, as a tutelary deity tutelary towards whom the gaze of so many artists who painted in Lucca between the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century turned (although, in the final stages of the tour, there is time for a brief lunge on the painting of Canova himself, and also to exhibit a group of unpublished works that will be discussed).

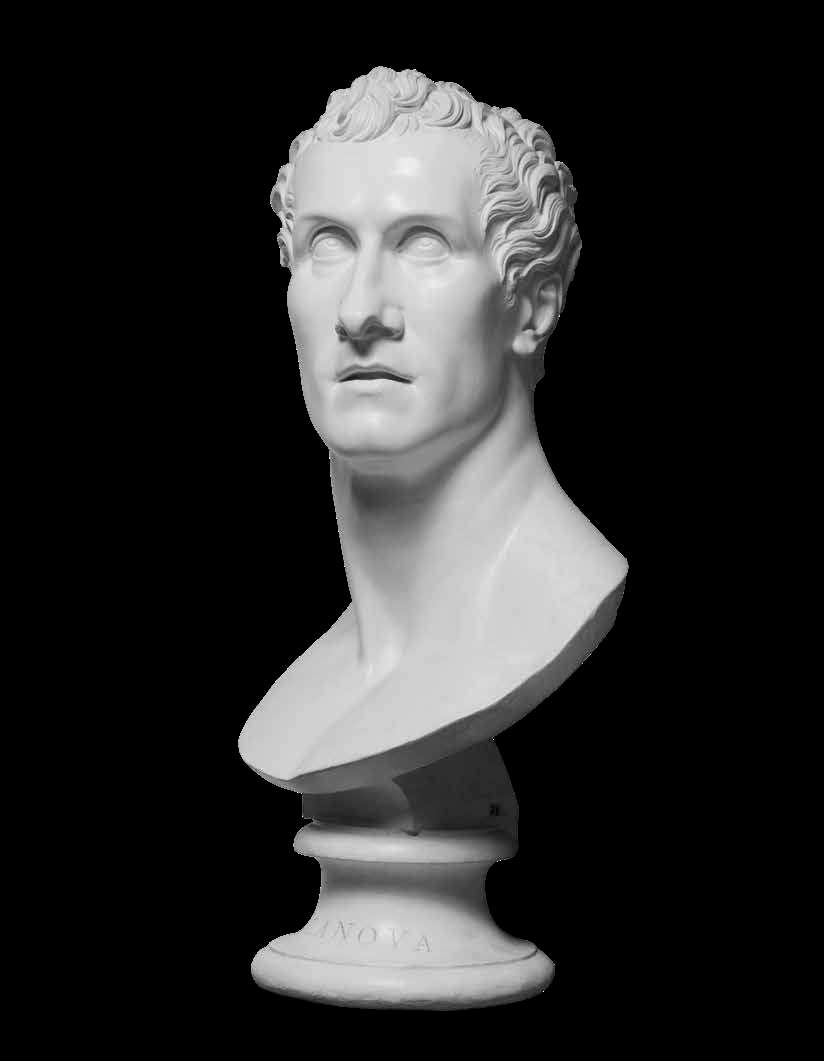

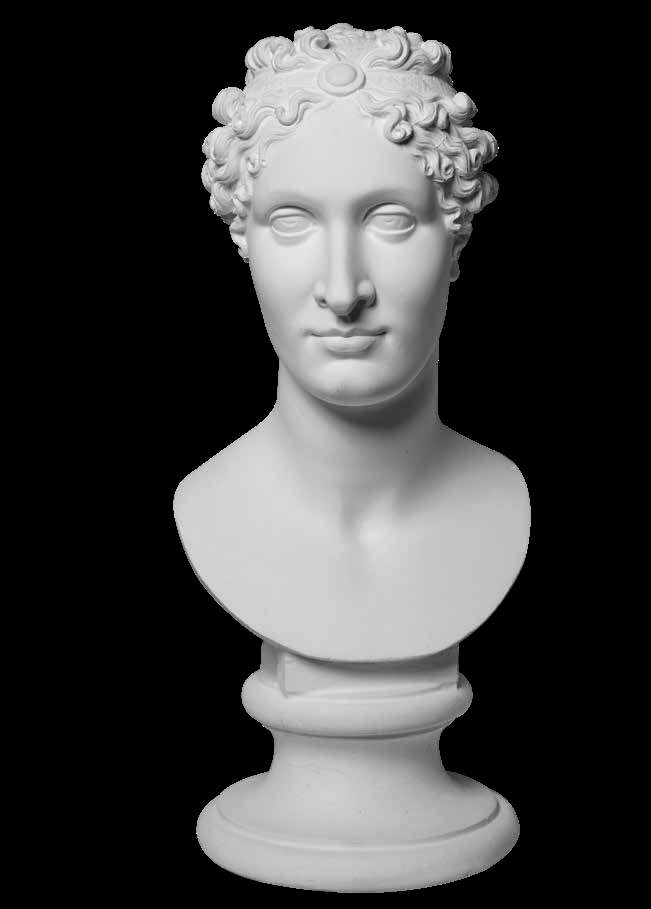

Canova’s deity is evoked at the opening of the exhibition by his self-portrait, which the Venetian sculptor executed probably accepting an invitation from his friend Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy: dated 1812, is a plaster cast that comes on loan from the Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, as opposed to most of Canova’s works in the exhibition, almost all of which are plaster casts that have instead been granted by the Gipsoteca Canoviana in Possagno. The opening of the exhibition establishes an immediate comparison between Canova and Pompeo Batoni, a very fine forerunner of neoclassicism, a disciple of Sebastiano Conca, active between Lucca and Rome (where he had begun his career as a highly appreciated portrait painter of grandtourists eager to bring back a souvenir of their trip to Italy), the prolific painter of the three popes, theartist who “went in search with much taste if not art of a composed and tranquil language, classical, but of a humanistic classicism inspired by the sixteenth century, Raphael and Correggio.” this is how Roberto Salvini described him seventy years ago. Batoni is, however, akin to Canova, although almost fifty years separate their birth dates, mainly because of the common gaze towards the past which, for both, is not merely a repertoire of forms, or a source from which to draw consistently on themes and subjects, but is also time to be studied, observed, and sifted with deep sensitivity in order to reach as full an understanding as possible of those forms, those monuments, and those subjects. Batoni, however, lacked the awareness that Canova, on the other hand, could inherit from the reflections of a Mengs or a Winckelmann: Batoni, because of his still late Baroque heritage (note in this regard his Atalanta che piange Meleagro morente, a painting recently acquired by the Fondazione Carilucca, which is among the peaks of the Cavallerizza exhibition, and which is still permeated by a taste for the scenic and a mellow subject matter that the neoclassicals would go on to mitigate, if not obliterate), as well as by the chronological limitations that matured his reflection on the antique before Winckelmann elaborated the founding theories of neoclassicism, cannot yet be said to be a neoclassical artist. However, his fundamental importance for Canova is evident, who, moreover, as a young sculptor who had just arrived in Rome, eager to learn and to know, would have gone so far as to declare that in the Urbe he would have found no other valentuomini in painting and sculpture than Signor Batoni da Lucca, whose private school the Venetian had wanted to attend, even preferring it to the public Accademia del Nudo on the Capitoline Hill.

Canova’s writings, after all, are filled with tributes to the Lucca master, but perhaps the most grateful and facetious homage is the one the Venetian would pay to Batoni in sculpture, first recalling his Atalanta inelaborating the pose of Temperance that appears in the Monument to Clement XIV, in the basilica of the Holy Apostles, and then taking it up again perhaps even more explicitly in the figure of Italy for the monument to Vittorio Alfieri, some twenty years later than the cenotaph for Pope Ganganelli: this relationship of dependence is well delineated in the first room of the exhibition, with the plaster of the turreted Italy in the center, suggesting the esteem and professional debts that Canova would have acknowledged to Batoni, whose great masterpieces will not be admired in the exhibition (for these one need only move to the National Museum of Villa Guinigi, not far from the Cavallerizza), but the selection made by Sgarbi is useful to understand the importance, far from secondary, of Pompeo Batoni in the framework of the developments of the neoclassical language, which the Lucchese was able to anticipate balancing, despite himself, on that very uncomfortable role, touched to many in the history of art, of continuator and precursor. Continuer, in this case, of a Roman painting that mitigated the Baroque overabundance by looking behind Guido Reni, Annibale Carracci and down to Correggio and Raphael, and forerunner of what at the time of Canova would have been called the “Baroque style.Canova’s time would be called the ”true style," since at the time no one knew he was neoclassical, a term coined in the late 19th century, first attested in 1877. Instead, it was among the greatest neoclassical standard bearers in the land of Lucca the still little-known Bernardino Nocchi, the third great protagonist of the exhibition along with Canova and Batoni. Indeed: perhaps Nocchi here is even something more than a supporting player, since for him the contours of a monographic exhibition almost loom large, somewhat as they did for Paolini last year: Nocchi, on the other hand, has never had exhibitions all to himself, and for him the Cavallerizza exhibition, bringing together twenty or so of his works from public and private collections (never before have so many of Nocchi’s works been seen together, and to complete the picture let us also add the exhibition curated by Paolini), is a monographic exhibition.add also the exhibition curated by Luisa Berretti, who exhibited his drawings at Palazzo Mansi in the spring), seeks to provide a precise framing, first presenting it together with some work by his master, the even less famous Giuseppe Antonio Luchi known as the Diecimino: he is 20 years old Nocchi when he paints his Self-Portrait arriving from the Uffizi, but compared to his mentor (see the coeval Portrait of Francesco Melchiorre Di Poggio, exhibited with its pendant, the Portrait of Maria Angela Sardini) one can see that he is already a painter of ’other scale, one understands how his ability to investigate the subject, his talent for bringing out the flesh tones, and the skill with which he brings out the fabrics from the canvas already mark a furrow between him and the less well-equipped Diecimino at the start of his career.

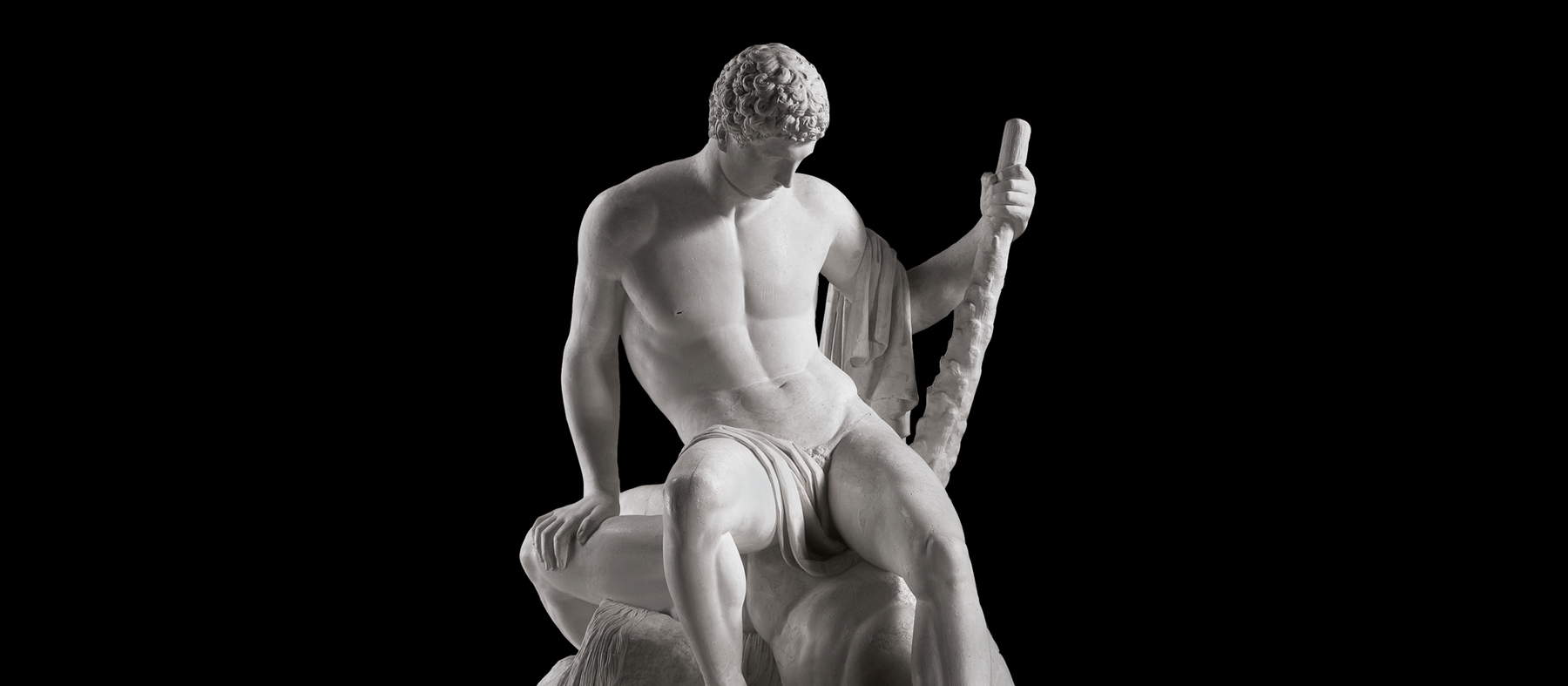

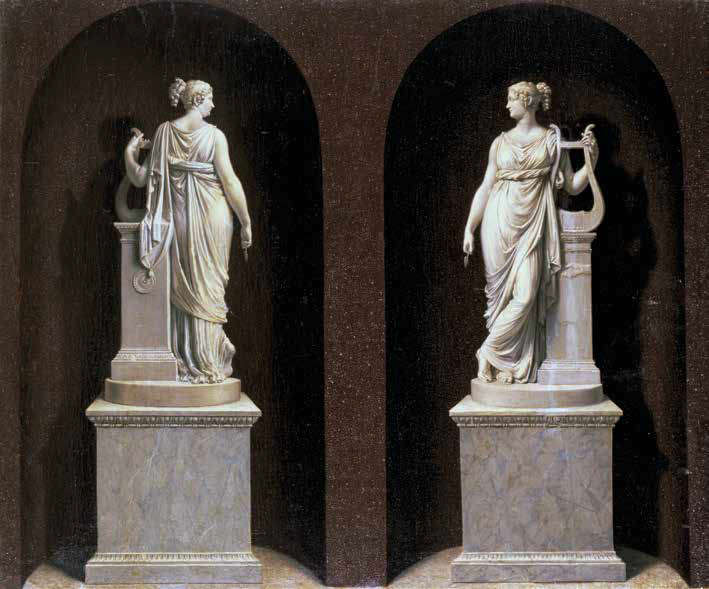

In tracing the career of Bernardino Nocchi, with several key works from his career (present, among others, are the sketches of some of the mythological subject scenes that the Lucca painter painted for Marcantonio IV Borghese in the rooms of his palace in Rome, or the Tobiolo and theangel in the Marignoli Foundation, all early works in which Nocchi shows himself still solidly attached to Batoni’s ideas), the exhibition seeks above all to bring out that turning point that Nocchi’s professional itinerary experienced after he made the acquaintance of Antonio Canova, of whom he would become a deep admirer. Here then Nocchi succeeds in diluting all those concessions to a certain still Roman exuberance, all that excess of the picturesque that still burdened the Tobiolo and the paintings executed in the same turn of years, to arrive at an orthodox, rigorous, clear neoclassical painting, pleasing to patrons, always mindful of Canova’s statuary: the Theseus, for example, can be understood as a reference for some of Nocchi’s works such as The Weeping of Ulysses (his model is also present, exhibited next to the final painting), or the Mercury Announcing to Calypso the Departure of Ulysses, which is among the masterpieces of the Lucchese painter’s mature phase, but the homage is sometimes direct and uncovered, as in the painting with the Tersicore that faithfully reproduces the Canovian statue.

Having outlined the premises, sketched an effective profile of the greatest interpreter of neoclassicism in Lucca, the exhibition takes to follow all its branches. First with the works of Stefano Tofanelli, a sort of settled and institutional alter ego of Bernardino Nocchi, together with whom he portrays himself in a beautiful self-portrait now preserved in Rome’s Palazzo Braschi: younger than Nocchi by about ten years, he had, however, studied with him in Rome, even sharing unfortunate episodes (neither of them had found acceptance at Batoni’s academy, so that they were forced to complete their training in the workshop of the late Baroque painter Nicola Lapiccola) and flanking his friend for a few years following their acquired artistic independence. Nocchi continued, however, to be an essentially wandering artist, working for the nobility of half of Italy, at ease with a wide variety of subjects, not disdaining even wall decoration. His colleague Tofanelli would also try his hand at fresco painting, but unlike his friend he preferred a more stable career: He stayed in Rome, became an academician of St. Luke’s, specialized in portraiture, and in 1802 returned to Lucca (Nocchi, on the other hand, stayed away from his homeland, though he continued to work occasionally for his fellow citizens), turned down theappointment as court painter in Madrid by Charles IV in order not to leave his homeland, continued to work for the Lucca aristocracy, after which, in 1805, he was presented with the opportunity to become the first court painter of the new princes Elisa Bonaparte and Felice Baciocchi. There is perhaps no artist who shaped the image of Napoleonic Lucca more and better than Stefano Tofanelli: a kind of Jacques-Louis David of the Serchio, one might say. In the exhibition catalog, Paola Betti credits him with "having imported to Lucca the protonoclassical language coined in his personal variant while being immersed in the fervent Roman cultural humus ." His portrait of Elisa Baciocchi appears next to the singular effigy in which Pietro Nocchi, son of Bernardino, captures the princess together with her daughter Napoleona Elisa caught in the act of flying some papers forming Napoleon’s name. The young Nocchi is among the first Lucchese neoclassicists to look insistently toward France: his work demonstrates, in particular, an acquaintance with the delicate, elegant, sometimes almost prissy portraiture of Marie-Guillemine Benoist, who is present with a portrait of Princess Élisa that surely embodies one of the high points of her official production. There is also room for the figure of Francesco Cecchi, a little younger than Nocchi and Tofanelli, an artist who has begun to re-emerge very recently from the mists of history (Paola Betti’s studies on him, the first that concern him, date back to a few years ago), and who in the exhibition appears above all in his dimension as an excellent portraitist, precise, meticulous and precise.excellent portraitist, precise and meticulous, and above all difficult to pigeonhole since he was refractory to all those inflictions that his contemporaries allowed themselves, and eager, if anything, to offer precise portraits of his subjects, bordering on a ruthlessness unknown to neoclassical painters (see the Portrait of Giacomo Sardini).

After tracing the various ramifications of neoclassicism in Lucca, the exhibition begins to stray to other parts of Italy, from Tuscany to the Veneto, in an attempt to show the Cavallerizza audience how the recovery of the myth operated by Canova was a common urge, engaging painters such as the Paduan Domenico Pellegrini, thearetino Pietro Benvenuti, the Leghorn-born Matilde Malenchini (a talented painter who deserves further study) and others, after which lingers on some paintings by Canova, and then returns to Lucca and moves toward the conclusion with some figures from the next generation, the one that became interested in the purism of Lorenzo Bartolini (who, moreover, was appointed by Elisa Bonaparte as director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara) and ferried Lucca’s arts toward Romanticism (there is also a portrait by Francesco Hayez to remind the visitor of the historical moment). In between there is also time for some unpublished works, as we anticipate: these are the twelve heads that Canova is said to have taken from as many of his works and that have recently resurfaced in the Canal family villa at Gherla, near Treviso: the Canal family inherited these and other Canova works from Giovanni Battista Sartori, Canova’s brother (he was born from his mother’s second marriage). Recognized as autograph works by Canova, they were recently purchased by Banca Ifis and published as autographs by Vittorio Sgarbi and Francesco Leone, who describe them as offering “a broad sampling of Canova’s production.” they are, in most cases, “casts from marbles, that is, plaster casts taken from the negatives, or hollow forms taken from the finished sculptures,” with two exceptions (the head of Paris and that of Beatrice) showing the marks left by the repère, the pegs used by the rough-hewn sculptors to take the proportions to be carried over to the marble works, a sign that these two heads served as models and were not made from the originals. Never exhibited before, never seen before, they are now on display in Lucca, as a set that is “testimony to the deep bonds that united Antonio and Giovanni Battista,” Sgarbi and Leone write, “and as an attestation of a whole life, that of Abbot Sartori, devoted to the celebration of the genius and the perpetuation of the myth and memory of Antonio Canova of Possagno.”

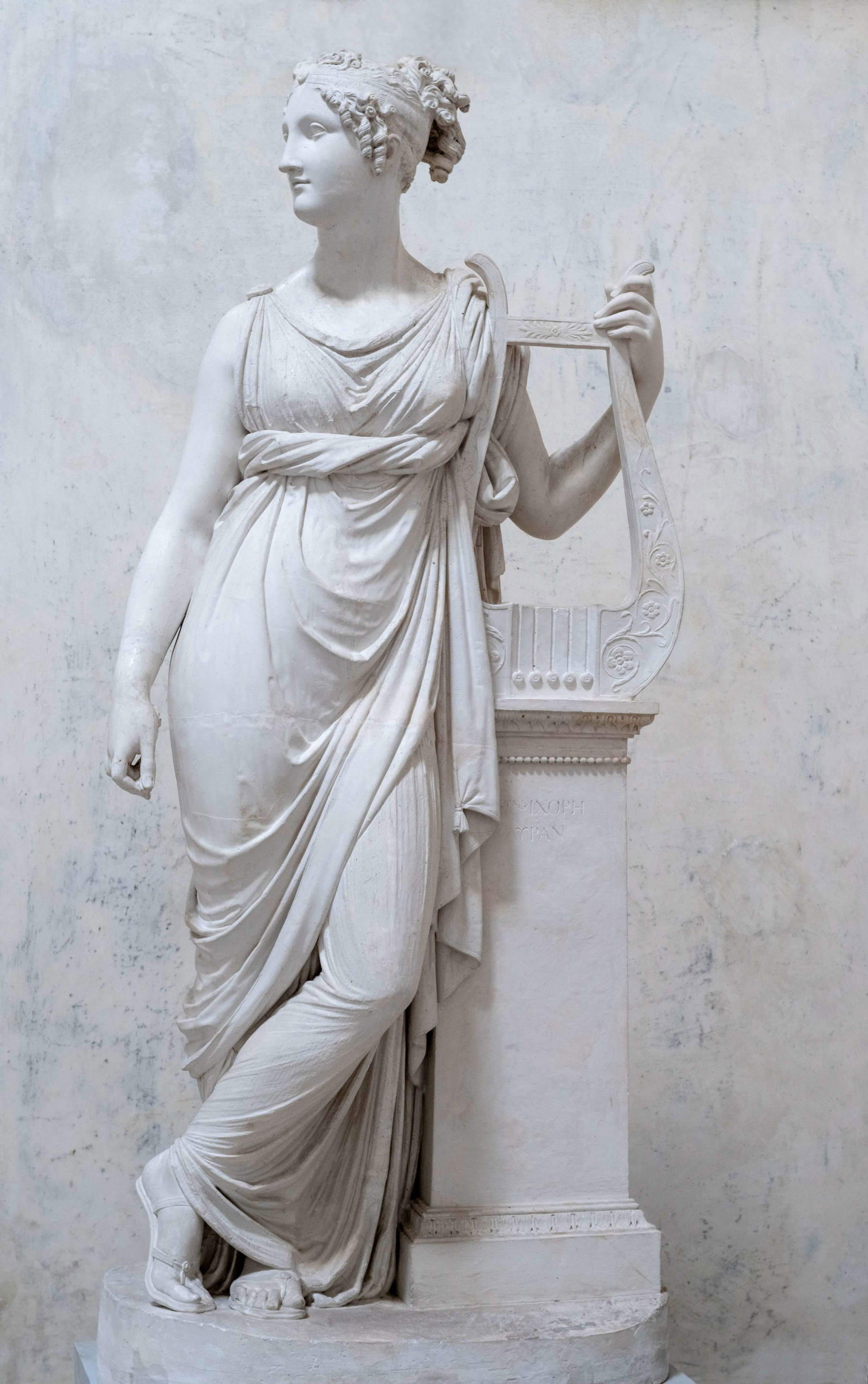

The very long trajectory of the exhibition (it will be worth remembering that the itinerary opens with an altarpiece by Giovan Domenico Lombardi known as the Little Man, a late 17th-century artist with whom last year’s review on Paolini closed) even allows itself a foray into the late 19th century: here then are first the mythological subjects of Raffaele Giovannetti, the versatile inspiration of Michele Angelo Ridolfi, and we even reach the threshold of the twentieth century with Michele Marcucci and Edoardo Gelli. The last appendix, the photographs of Fabio Zonta, conclude the itinerary: it is the admirable series on Canova, which was also the focus of an interesting exhibition at the Museo Civico di Asolo a couple of years ago. It is only a pity that the images are set up on the walls of the bookshop and run the risk of acting as a set design, an embellishment for a book and gift store, and that therefore the public does not give Zonta’s shots the attention that it would have given to the photographs in a different location.

It is curious to note that the end of the careers of Lucca’s leading neoclassicists coincided in an almost overlapping manner with the end of the Napoleonic principality: Nocchi would remain far from Lucca and died in Rome in 1812, a few months before his friend Tofanelli, who failed to finish the decorations that Elisa Bonaparte had commissioned from him for the Villa di Marlia, which is perhaps the symbol in architecture of neoclassical Lucca. Instead, a few more years survived Francesco Cecchi, who passed away after 1822. The Restoration and the transformation of Lucca into an unprecedented duchy would begin a new season, that of the governments of Maria Luisa of Bourbon and Carlo Lodovico of Parma, that of the city modeled by the great architect Lorenzo Nottolini, that of the undertaking of the renovation of the Ducal Palace that would involve various artists, from Luigi Ademollo to Giuseppe Collignon, the city in which the purist language of Raffaele Giovannetti spread. A season that in the exhibition is just touched upon: Canova, by then, was no longer a point of reference.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.