by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 07/01/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Canova, Hayez and Cicognara. The Last Glory of Venice' at the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice until July 8, 2018.

The most interesting, valuable and profitable way to celebrate the anniversary of the founding of a museum is to retrace the first years of its history through a sensible exhibition, far from any futile rhetorical intentions, set up on a path capable of being highly communicative to the general public expected to visit it, and in addition strong in a message that stands out for its urgent relevance. Such is the scope of Canova, Hayez and Cicognara. The Last Glory of Venice, the exhibition that falls on the bicentennial of the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and which the public can enjoy until next April 2. The exceptional trio that appears in the title, an apparent concession to a fashion that wants in the titles the names of the greatest to shore up the exhibition’s scaffolding, actually serves as a map that allows visitors to orient themselves among theexhibition’s themes, fixing the points around which the scientific project curated by Paola Marini, Fernando Mazzocca and Roberto De Feo revolves.

Antonio Canova (Possagno, 1757 - Venice, 1822): one of the protagonists of the recovery of the works that left Italy during the Napoleonic spoliations, the most celebrated artist of his time, the great animator of the early years of the Gallerie dell’Accademia. Leopoldo Cicognara (Ferrara, 1767 - Venice, 1834): the refined intellectual who, as president of the institute in its early years, more than any other was able to give substance to the ambitious dream of reviving the arts after one of the most convulsive periods in Venetian history. Francesco Hayez (Venice, 1791 - Milan, 1882): the rising star, the young man of great hopes on whom Canova and Cicognara bet (with happy intuition, given the results that would result from their action) in order to give impetus to their project. Neither the artist nor the intellectual, in fact, rested on the glories of the Venice of the past: the design of their Gallery envisaged that, alongside a moment for conservation, there would also be a moment for the support ofcontemporary art. Ancient art, in other words, was seen as the sap and nourishment for contemporary art, which was and still is produced near the museum: in fact, the Galleries were born within theAccademia di Belle Arti di Venezia (which even today continues to have its headquarters not far from here), and the Galleries’ own collection was initially enriched with works by students of the Accademia, as well as contemporary artists to whom a special room was dedicated. For the Galleries, Cicognara envisioned a dual function, one reserved for students, who through the ancient examples could consolidate their skills and knowledge, and the other for the public: the Galleries were in fact conceived with the precise intention of being open to visits by any citizen, since the great theorist was very clear about the role of art in the formation of civic sense.

Cicognara’s work was animated by Enlightenment convictions: after the Congress of Vienna and the return to the city of some of the most symbolic works among those that the French had taken to Paris after having caused, in 1797, the end of the millenary Republic, Venice found itself with a huge amount of works of art, mostly coming from churches and buildings belonging to the ecclesiastical orders suppressed during the French occupation, which needed to be given a new life. Paintings, drawings, sculptures, and books found accommodation in the complex of the old Scuola della Carità, former property of the suppressed order of the Lateran Canons, which was identified as the site of the Gallerie dell’Accademia: the latter opened its doors to the public in 1817. For the Venetians it was a significant event that, in a way, went some way to reinvigorate spirits after the fall of the Republic: a fall that, moreover, Canova never forgave Napoleon, despite the fact that the future emperor had called him to France to execute his portrait while he was still first consul. Wrote Antonio D’Este, one of the earliest biographers of the great sculptor from Possagno: “Greater sorrow did he feel for the transportation of the horses of Venice and the subversion of that ancient republic, telling the first consul, that those were things that would afflict him all the time of his life.”

|

| The entrance to the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice at the exhibition Canova, Hayez and Cicognara. The Last Glory of Venice |

|

| The entrance to the exhibition |

|

| The first room of the exhibition |

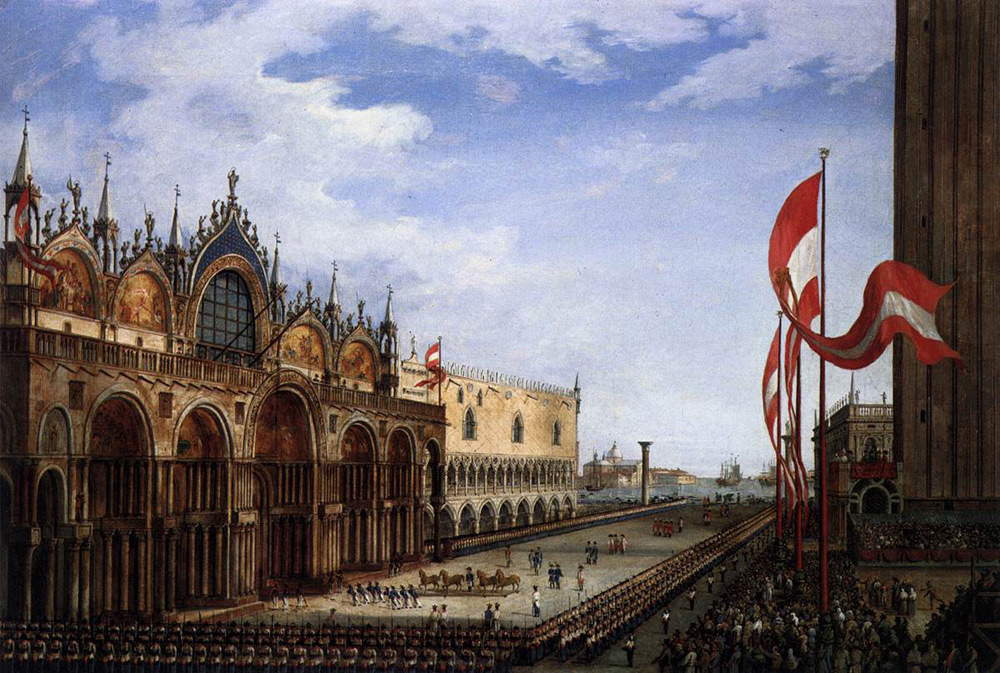

The narrative of the exhibition opens precisely with the important episode of the return of the bronze horses of St. Mark’s, removed from the Basilica on December 13, 1797, and later transported to France to be first placed at the entrance to the Tuileries and then hoisted to the top of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel. The four great horses were themselves, however, spoils of war, since the Venetians had taken them in 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, from Constantinople (dating back to classical antiquity, although scholars disagree on the dating, the horses had been intended for the hippodrome of what became the capital of the Eastern Empire), but their departure for Paris was seen as an intolerable snub, and their return to the lagoon was considered an absolute priority. Thus, following Napoleon’s final defeat, the Austrian government was able to offer its support to the city and, in a solemn ceremony celebrated in 1815 (on the symbolic date of December 13), the horses were once again placed on the terraces of San Marco. The works on display recount different moments in the horses’ story: an etching by Carle Vernet (Bordeaux, 1758 - Paris, 1836), one of Napoleon’s closest artists, narrates the entry of the French into Venice (and we see them as, in the center, they are already carrying away the horses from St. Mark’s); another etching, but by Luigi Martens, itself taken from a drawing by Giuseppe Borsato (Venice, 1770 - 1849), returns us to the horses as they disembark on the small square behind the Doge’s Palace (they arrive on a barge accompanied by a large number of boats), and finally an oil by Vincenzo Chilone (Venice, 1758 - 1839) offers evidence of the solemn ceremony of redeployment, with the horses arranged on wagons being dragged in front of the Austrian army, deployed on two wings on either side of St. Mark’s Square, and the authorities who instead find a place on a tribune under the bell tower.

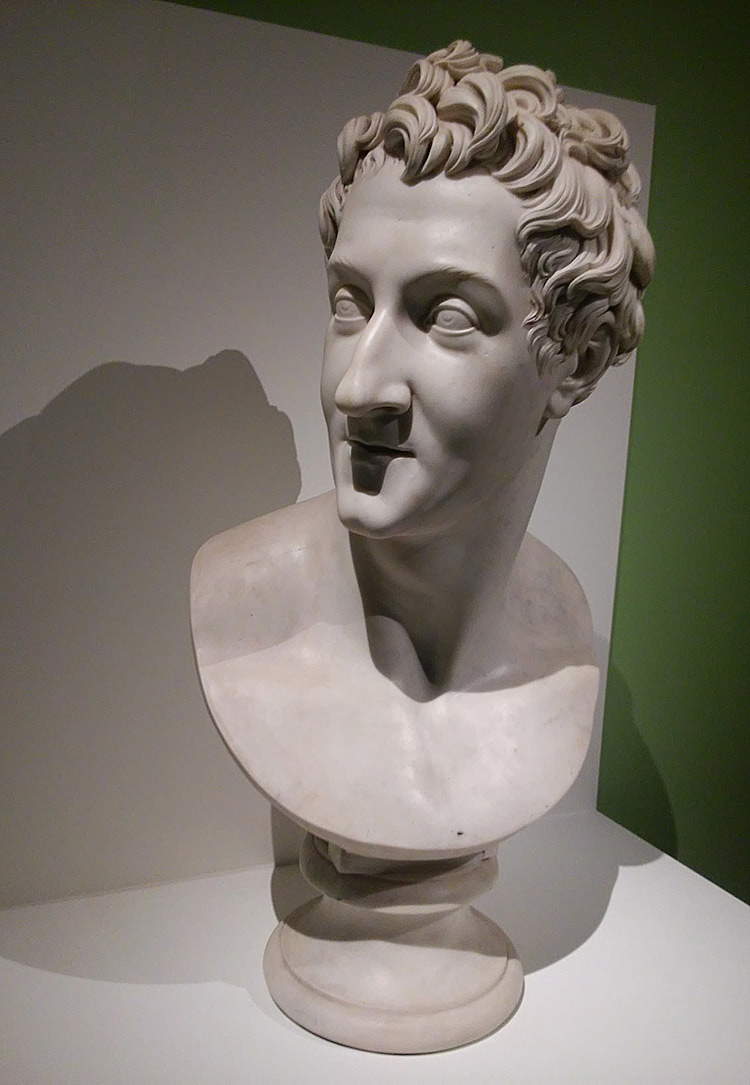

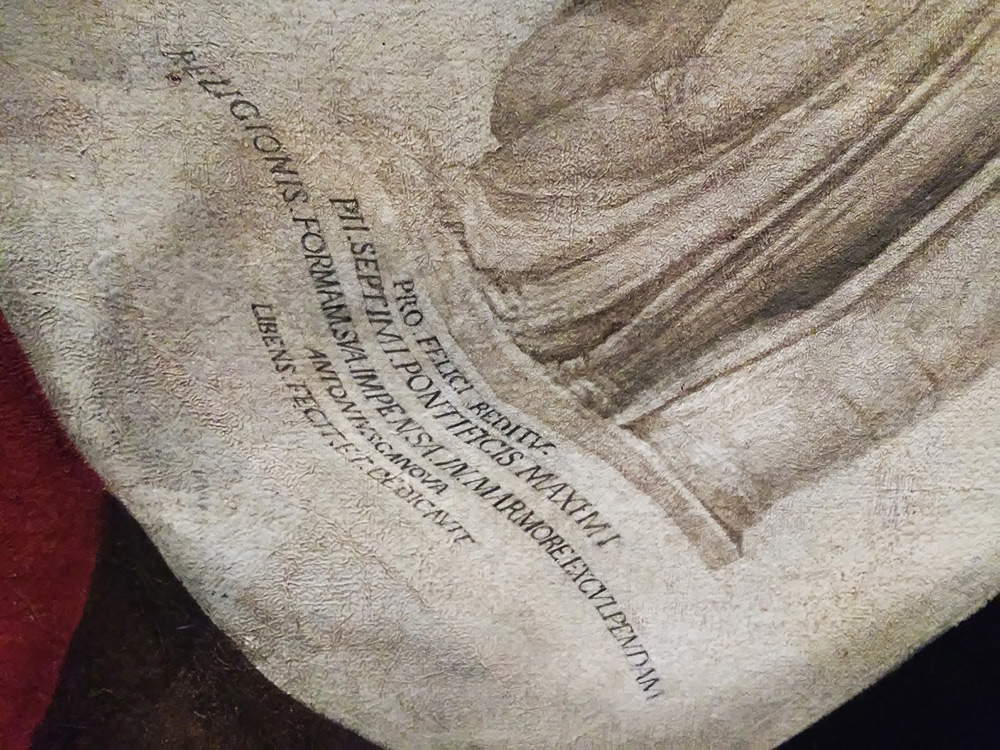

This was the event that kicked off the Venetians’ new ambitions for glory: standing out above them all, in terms of passion, stubbornness, will and foresight, was the then president of the Academy of Fine Arts, Leopoldo Cicognara, to whom the next section of the exhibition is dedicated. The Ferrara count is presented as the man who pursued the goal of uniting the protection of ancient works with the promotion of contemporary artists, activities in the sphere of which he received the decisive help of Antonio Canova: to seal this enduring friendship, the exhibition features the bust-portrait of Cicognara, executed by Canova between 1818 and 1822 and destined to be placed on the nobleman’s tomb in the Certosa of Ferrara. Cicognara is also presented to us as the formidable discoverer of talents who, first of all, noticed the inspiration of Francesco Hayez: in him, the count saw the ideal candidate to restore Italian painting to its former glories, a sort of alter ego of Canova, who had already achieved the goal in sculpture. The Canova-Cicognara-Hayez relationship is exemplified by a key painting, the portrait of the Cicognara family, depicted by the young Hayez beneath Canova’s colossal bust, with the count and his wife Lucia Fantinati holding in their hands a print of the Catholic Religion (also on display in the exhibition), a sculpture that the Possagno genius had envisioned (and never made) for St. Peter’s Basilica in order to celebrate the return to Rome of Pius VII, a prisoner in France after the Napoleonic occupation of the Eternal City. Hayez’s role as a continuer of the great Venetian tradition, however, is underscored by the torn frescoes in the Doge’s Palace: the artist, working in the palace with a commission obtained thanks precisely to Cicognara, was able to measure himself against the most distinguished Venetian painters of times gone by, and the exhibition in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, with the Tritone playing the buccina on a seahorse and the Venus between Eros and Anteros, also gives us an account of the high models (Raphael, Giulio Romano) to whom Hayez looked in the early stages of his career, and whose study he perfected with a stay in Rome strongly advocated by Cicognara himself.

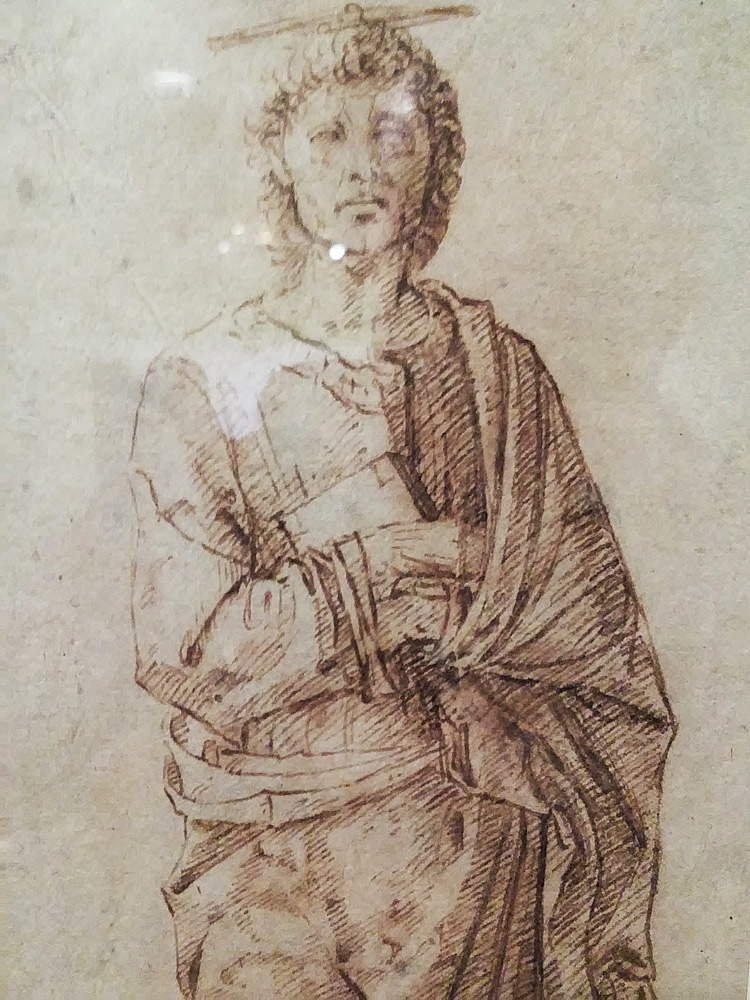

In a small room that the visitor finds after the large hall that houses the first sections of the exhibition, one of the fundamental moments of the first years of the Accademia Galleries’ life is documented: the arrival in Venice of the collection of drawings that belonged to Giuseppe Bossi (Busto Arsizio, 1777 - Milan, 1815), which the Austrian government acquired (at Cicognara’s suggestion: almost superfluous to specify) with the specific purpose of turning it over to the Accademia. Bossi had amassed an enormous graphic collection consisting of about one thousand five hundred folios by great artists of the past, and the purchase went to meet the need to endow the Academy of Venice with a graphic heritage on which to have its students study, and which it did not have at the time. Giuseppe Bossi’s collection was the ideal candidate in terms of range (the Lombard artist had collected works ranging from the 15th century to contemporary times) and vastness: in the room we therefore find sketches by Mantegna, Parmigianino, Rembrandt, Giulio Cesare Procaccini, and Perugino. For purely conservative reasons, the exhibition had to give up exhibiting the most famous sheet in the collection: theVitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, kept at the Galleries precisely because it too was included in the Bossi collection.

|

| Carle Vernet, The Entry of the French into Venice (1799; etching; Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Gabinetto Stampe e Disegni del Museo Correr) |

|

| Luigi Martens da Giuseppe Borsato, The landing of the horses at the piazzetta (1815; etching; Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Gabinetto Stampe e Disegni del Museo Correr) |

|

| Vincenzo Chilone, The ceremony of the relocation of the bronze horses on the pronaos of St. Mark’s basilica (1815; oil on canvas; Private collection) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Venus between Eros and Anteros (1819; torn fresco; Venice, Museo Correr) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Portrait of Leopoldo Cicognara (1818-1822; marble; Ferrara, Musei Civici di Arte Antica) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Portrait of the Cicognara Family (1816-1817; oil on canvas; Venice, Private Collection) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Portrait of the Cicognara family, detail |

|

| Domenico Marchetti da Antonio Canova, The Catholic Religion (1816; etching with burin; Bassano del Grappa, Museums Library Archives) |

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Saint John the Evangelist (pen and brown ink on white paper; Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

Art history and politics intertwine in the room where the curators wanted to recall thetribute of the Venetian provinces to the court of Vienna, another episode that gives us an account of Leopoldo Cicognara’s intelligence and subtlety. In 1817, when Emperor Francis I of Austria married Caroline Augusta of Bavaria, a huge tribute of ten thousand gold ticks was imposed on the Venetian provinces as homage to the newlyweds: however, this was an unbearable burden for the territory. Cicognara, in a most brilliant diplomatic move, on the grounds that the Austrian treasury had already been abundantly replenished by taxes secured from the Lombard and Austrian provinces, proposed to the government in Vienna that the onerous tax be converted into donations of works of art to adorn the apartments of the Austrian court. The works, produced for a value that matched the equivalent of the amount requested, would be made by the best artists in the Veneto region: the empire accepted the proposal. The exhibition, exactly two hundred years after the event, brings back to Italy some of the sculptures that the Venetian artists made for the Viennese apartments, even managing to suggest to the visitor, with the jade green of the settings, the colors of the apartment of the Hofburg, the imperial residence, for which the works were imagined. It is certainly the most spectacular setting of the exhibition.

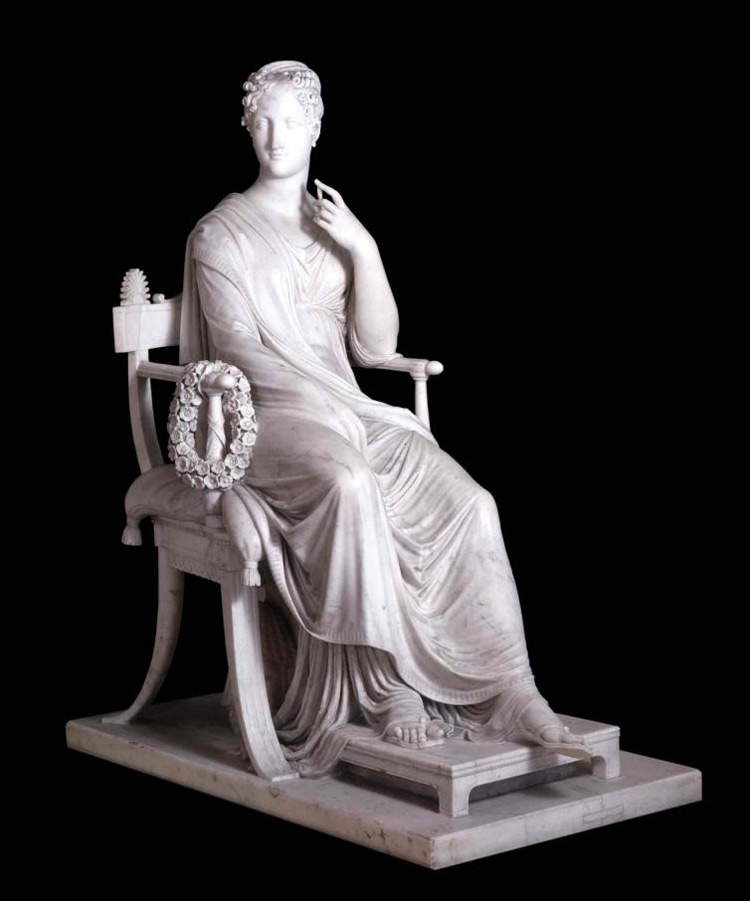

Of course, also convincing the Austrian government was the possibility of including, in the lot of works, a sculpture by Canova: in this case, the Musa Polimnia, a work of great refinement that the sculptor created as a portrait of Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi, but never delivered to the former Grand Duchess of Tuscany, since at the fall of the Napoleonic regime the work had not yet been completed. The tribute granted Canova the opportunity to complete the work, which was exhibited at the Accademia in Venice before being sent to Vienna. The muse of Canova’s story did not fail to arouse wonder in those who observed its fine modeling, the smoothness of the surfaces, the gracefulness of the pose, the extreme care with which the sculptor had rendered the draperies, the delicacy of the face and the left hand that with its index finger grazes the neck caressing it with elegance. One of the greatest men of letters of the time, Melchiorre Missirini, had to write that “this statue of the Muse Polyhymnia is placed by the Masters of Art among the most beautiful works of Canova [...]. The monument is of singular merit, whether one regards the utmost and divine beauty of the semblance, or the elegance of the whole person seated in her graceful act and full at once of dignity, or the drapery conducted with the most exquisite taste, or the execution drawn to that last finish of softness, suavity and truth, which matter can have.” Other noteworthy sculptures include a Chiron instructing Achilles in music by Bartolomeo Ferrari (Marostica, 1780 - Venice, 1844), a work of wholly neoclassical refinement and, like other works executed for the tribute, later left the Hofburg to go on to decorate other residences of the Austrian court, as well as the two vases, executed one by Giuseppe de Fabris (Nove, 1790 - Rome, 1860), the other by Luigi Zandomeneghi (Colognola ai Colli, 1778 Venice, 1850) on the model of the great antique vases, such as the Borghese vase, and like the latter decorated on the rim with bas-reliefs (in this case, given the sentimental vicissitudes of the patron, with nuptials from antiquity).

|

| The room of the exhibition dedicated to the homage of the Venetian provinces. |

|

| Antonio Canova, Musa Polymnia (1812-1817; marble; Vienna, Hofburg, Kaiserappartements) |

|

| Bartolomeo Ferrari, Chiron instructs Achilles in music (after 1826; Artstetten, Castle Collection) |

|

| Giuseppe De Fabris, Vase with the Wedding of Alexander and Roxane (1817; marble; Vienna, Hofmobiliendepot, Möbel Museum) |

|

| Luigi Zandomeneghi, Vase with the Wedding of Aldobrandini (1817; marble; Vienna, Hofmobiliendepot, Möbel Museum) |

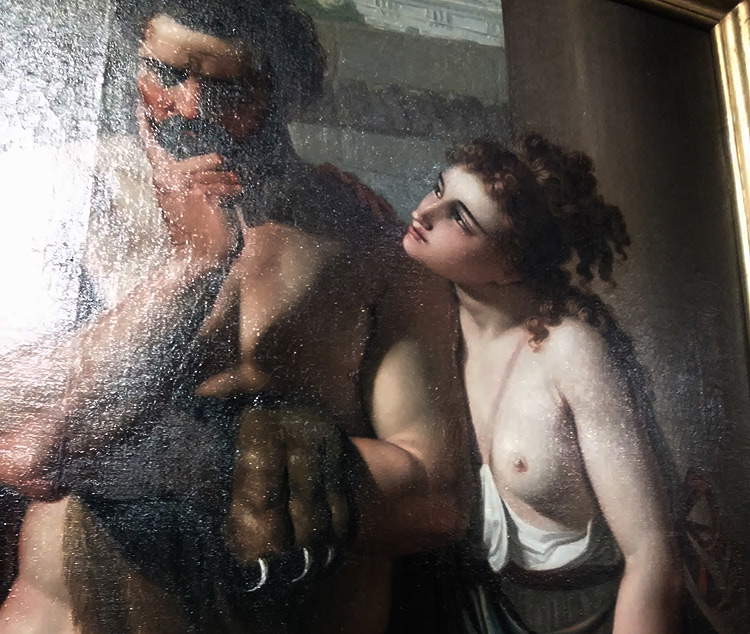

The next room aims to introduce the public to some of the best artists who took turns among the classrooms of the Venice Academy between 1815 and 1822, the narrow period the exhibition examines. The students were eligible to compete for a grant that guaranteed them a boarding school in Rome in order to study the high examples that the capital of the Papal States could offer them, and once they had obtained their coveted stay they were required to account for their progress by sending essays to Venice: the powerful Hercules at the crossroads that we see in this room is precisely one of the essays that Giovanni De Min (Belluno, 1786 - Tarzo, 1859) elaborated in Rome, and it is distinguished by the vigor of the Hercules in the center and the veridical sensuality of the Venus, depicted on the right in an attempt to convince the mythological hero to take the path of earthly passions, as opposed to the Minerva who instead invites him to walk the more tortuous path of virtue. Among the high points of the exhibition is the comparison between Francesco Hayez’s Rinaldo and Armida and Fabio Girardi ’s Cephalus and Procri (1792 - 1866/68): a comparison from which Hayez undoubtedly emerges the winner for the freshness of the nude that looks to Canova’s sculptures (the resting arm is the same as that of Paolina Borghese) as well as to the procaciousness of the Titian heroines, for the pose at once natural and ingenious, for the way the fabrics are treated, for the depth of the landscape and the insertion of the figures within it, and for the marked eroticism, anticipatory of many paintings that would make Hayez one of the most sensual painters of the entire 19th century.

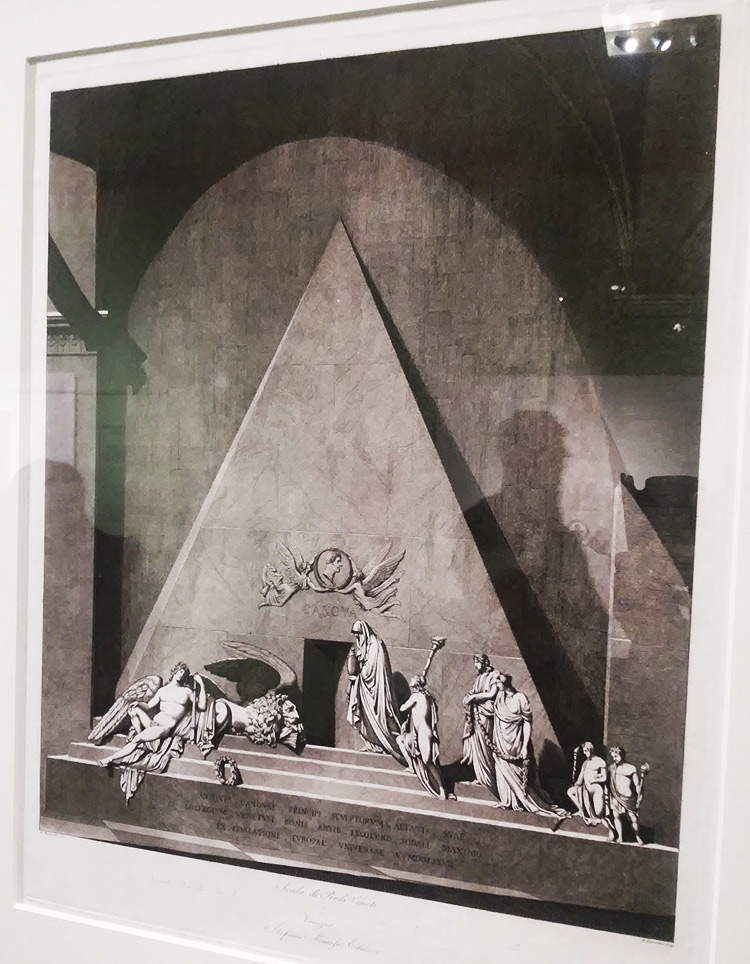

Having passed the small “interlude” on the figure of Lord Byron, who was present in Venice between 1816 and 1819, the exhibition moves on to examine the myth of Canova ’s “national glory and universal icon,” celebrated almost as a modern hero, since he was not only a supreme artist who surpassed all his contemporaries, but with his diplomatic efforts in France he was also hailed as a skillful politician who managed to bring back to Italy a good part of the treasures taken away during the Napoleonic occupation. Merits that earned him the erection of a monument in the basilica of the Frari, designed by two students of the Accademia, Antonio Bernatti and Antonio Lazzari, along the lines of the one that Canova himself, in 1790, had imagined for Titian, but which was never realized because of the political vicissitudes that the Serenissima went through. More fortunate fate had instead the monument conceived for Canova: we see it today majestic, with its Carrara marble pyramid at the center of which is the door of the mock mortuary towards which approach, on the right, the personifications of sculpture, painting and architecture accompanied by three genii, while on the left we meet, afflicted, the genius of Canova and the lion of Venice. The idea of being inspired by the model of what was to become the monument to Titian was proposed by Cicognara: a painting by Giuseppe Borsato shows the count as, inside the basilica, he illustrates the monument, which today houses Canova’s heart. It is interesting to point out that, according to a custom usually reserved for saints, Canova’s remains are kept in different locations: of the heart has already been mentioned, the body is kept in the temple of Possagno, and the right hand in an urn at the Accademia in Venice.

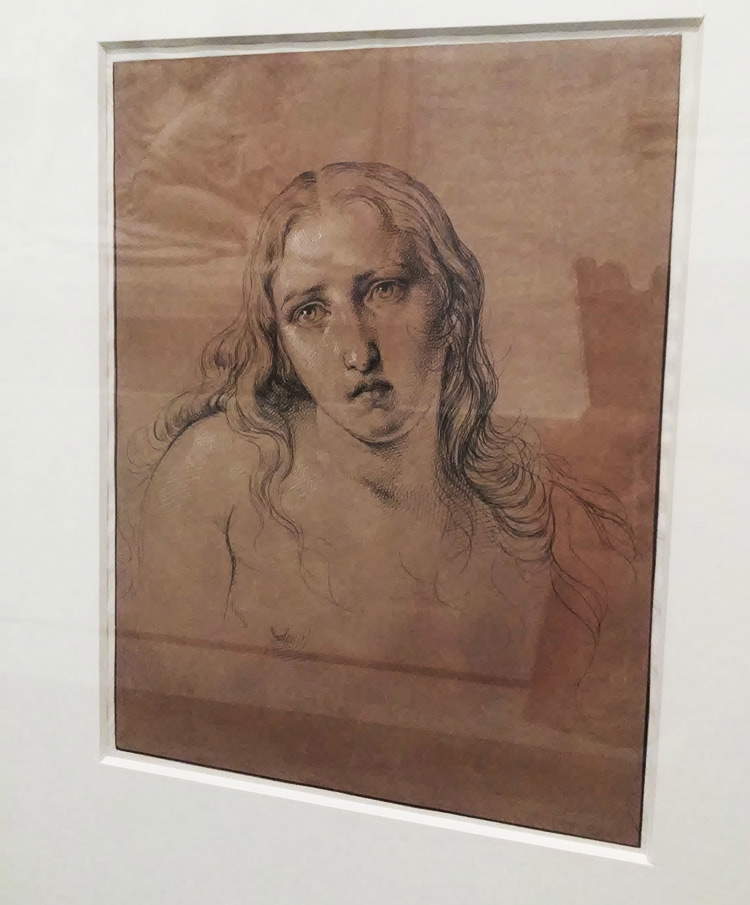

The exhibition draws to a close with a corridor devoted entirely to Francesco Hayez. 1822 is the year that saw the death of Canova and Hayez’s departure from his hometown, and for these reasons it is also the year that concludes the discourse of the exhibition: in Milan, where he would later move, Hayez had the opportunity to ideally cultivate Cicognara’s project, giving life to that original historical romanticism that connoted the artist’s stylistic signature and oriented the themes of his painting (a painting to which, moreover, many wanted to attribute political meanings). One of the most significant paintings of his entire output, the Pietro Rossi of the Brera Art Gallery, is among the most important works of the century, since it introduced a fundamental novelty: for the first time an artist went fishing in the repertoire of modern rather than ancient history. In fact, the episode narrated dates from the 14th century and depicts the moment when Pietro Rossi, lord of Parma, is invited by the Venetians to take command of the Serenissima’s army against the Scaligeris, who had stripped him of his dominions. All this while, inside the Pontremoli castle where the story takes place, his wife and daughters beg him not to leave. The rest of the corridor is a roundup of works by Hayez, ending with the drawing of Mary Magdalene included in the itinerary to document how the contacts between the painter and Cicognara had continued even after his departure for Milan: Hayez sent the sheet to the count in order to give him the opportunity to enrich the album in which he kept the drawings of the artists with whom he had maintained relations.

|

| Giovanni De Min, Hercules at the Crossroads, detail (1812; oil on canvas; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia) |

|

| The comparison between Francesco Hayez and Fabio Girardi |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Rinaldo and Armida (1812-1813; oil on canvas; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Rinaldo and Armida, detail |

|

| Fabio Girardi, Cephalus and Procri (1817; oil on canvas; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Monument to Titian (1790; wood and terracotta model; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia) |

|

| Antonio Bernatti and Antonio Lazzari, Monument to Canova (1827; etching and aquatint; Milan, Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, Prints Collection) |

|

| Giuseppe Borsato, Leopoldo Cicognara Illustrates Canova’s Monument at the Frari (1828; oil on canvas; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Pietro Rossi at Pontremoli (1818-1820; oil on canvas; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Study for the Penitent Magdalene (pencil and white lead on paper; Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Gabinetto Stampe e Disegni del Museo Correr) |

Cicognara himself, in 1828, found himself complaining to Hayez about the scarcity of work that Venice offered its most capable artists: “The fact is that the poor young men who succeed must always go away to earn their bread.” It has been mentioned how the Accademia was forced, starting as early as the 1920s, to deal with a market that, after the occupation, was still struggling to restart, and with a public patronage that, in relation to art, had much less interest than in the past. This stalemate situation was therefore detrimental to Venice, which in the following years saw the importance of its own role in international and even national artistic affairs diminish more and more, and proof of this is the fact that Francesco Hayez’s career had to continue far from Venice and flourish in the city that, in the nineteenth century, assumed primacy, at least in northern Italy: Milan.

The exhibition’s themes do not end with the eight rooms on the ground floor. The entire itinerary of the Gallerie dell’Accademia is studded with panels that extend the discourse begun with the exhibition, and even with loans arrived for the occasion: the public will thus be able to admire Andrea Mantegna’s Madonna and Child with a Chorus of Cherubs, which returns to Venice (the French had in fact removed it from the church of Santa Maria Maggiore and sent it to Brera in order to enrich the collections of the local picture gallery, where it is still preserved) to be set against Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna of the Red Cherubs. A comprehensive exhibition on the beginning of a two-hundred-year-long story, a comprehensive review that allows the visitor to reread several works of the collection as well, an exhibition that addresses to the public (we reiterate, since it is certainly one of the most interesting aspects) a message of great topicality, at a historical moment in which protection is certainly not going through good times and contemporary art is suffering peaks of incommunicability about which we need to question ourselves more and more deeply. Cloaking the art of the past with a scope that can help us probe the present is one of the points that should guide the action of a museum: in this sense, Canova, Hayez and Cicognara. The Last Glory of Venice, an intelligent, successful and philologically correct exhibition, can be said to be an operation that can, at least, make us wonder whether what we do for art today can be considered worthy of those who came before us.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.