by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 18/06/2020

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Canova - Thorvaldsen. The Birth of Modern Sculpture," in Milan, Gallerie d'Italia, Piazza Scala, from October 24, 2019 to June 28, 2020.

Milan had to content itself with being irradiated by a lightning-fast reverberation of the dispute that pitted the two great rivals of neoclassical sculpture, Antonio Canova (Possagno, 1757 - Venice, 1822) and Bertel Thorvaldsen (Copenhagen, 1770 - 1844): here, on Lombard soil, fortune did not come to the Venetian who, amid shelved projects, works that never reached their destination and interrupted intentions, often missed the opportunity to impose his genius there, while still managing to shine its star: think of the bronze of Napoleon as Mars the peacemaker that has towered over the courtyard of Brera since 1859, the plaster casts of the Accademia, the marble cippus to Giuseppe Bossi, erected at the Ambrosiana where it still stands. Of the Scandinavian, on the other hand, the city preserves only the cenotaph of the poetess Anna Maria Porro Lambertenghi, now protected by a glass window between the tables of the bar at Villa Reale: for a closer comparison between the two, it is necessary, if anything, to go not far from the capital, to the Villa Carlotta in Tremezzo, where the most shining example of neoclassical bas-relief,Alexander’s Entrance into Babylon, a masterpiece by the Dane, dialogues with some of Canova’s best works that Giovanni Battista Sommariva, a great lover of the Possagno sculptor, wanted for his own collection. Until June 30, however, one more chance is given, and right in Milan, to see Canova and Thorvaldsen side by side: the exhibition Canova Thorvaldsen. The Birth of Modern Sculpture, on display until next June 28 in the rooms of the Gallerie d’Italia in Piazza Scala.

This is an extraordinary first: never before have the works of Canova and Thorvaldsen been exhibited side by side in a single exhibition event exclusively centered on the comparison between the two. That parallel, which, until now, had been possible only through study, or had at most taken the form of a few quick duels in the context of exhibitions devoted to delving into other topics, comes to life in Milan with an event of exceptional quality: the two curators, Fernando Mazzocca and Stefano Grandesso, among the world’s foremost scholars of the two masters, have ordered a superlative itinerary, which scholars and devotees of neoclassical art had been waiting for, and which we have no difficulty in inscribing among the best exhibitions of the last ten years at least. An exhibition that is, first and foremost, the story of a dream, pursued first by Canova and then by Thorvaldsen, and in which one can identify the basis for that birth of modern sculpture that gives the exhibition its title: the ambition to give life to a new way of conceiving sculpture and its function, which was to be untied from decorative or devotional intentions, and which on the contrary was to become independent and the bearer of universal feelings and values. In order to give substance to the dream, the Winckelmannian concept of “imitation” had to be declined in a modern sense, it was necessary to revolutionize the ways of working in the workshop, and it was an obligatory step to rethink the very role of the artist vis-à-vis the public and patrons.

But the Milanese exhibition is also, of course, the narration of a challenge, although the antecedent can only be suggested, since the two works that would make it possible to tell the story on site of how it all began are missing, that is, when, in 1801, Canova tried his hand for the first time at the heroic genre by sculpting a triumphant Perseus that intended to compete with theApollo of Belvedere, charging his work with contemporary meanings. Thorvaldsen, in his turn, had challenged Canovian’s gentle Perseus with a Jason who towered over him in power and virility: critics in the German area were immediately enthusiastic about the 30-year-old from Denmark, unilaterally decreed Thorvaldsen’s superiority in the heroic genre, and started a tussle that was destined to last for decades. Humboldt, Schlegel, Fernow and other great critics of the time had harbored no hesitation: not only could Thorvaldsen hold his own against the greatest European sculptor of the time, he could even beat him.

|

| Hall of the exhibition Canova Thorvaldsen. The birth of modern sculpture. Ph. Credit Flavio Lo Scalzo |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Canova Thorvaldsen. The birth of modern sculpture. Ph. Credit Flavio Lo Scalzo |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Canova Thorvaldsen. The birth of modern sculpture. Ph. Credit Flavio Lo Scalzo |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Canova Thorvaldsen. The birth of modern sculpture. Ph. Credit Flavio Lo Scalzo |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Canova Thorvaldsen. The birth of modern sculpture |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Canova Thorvaldsen. The birth of modern sculpture |

The personalities, the ateliers, the glory

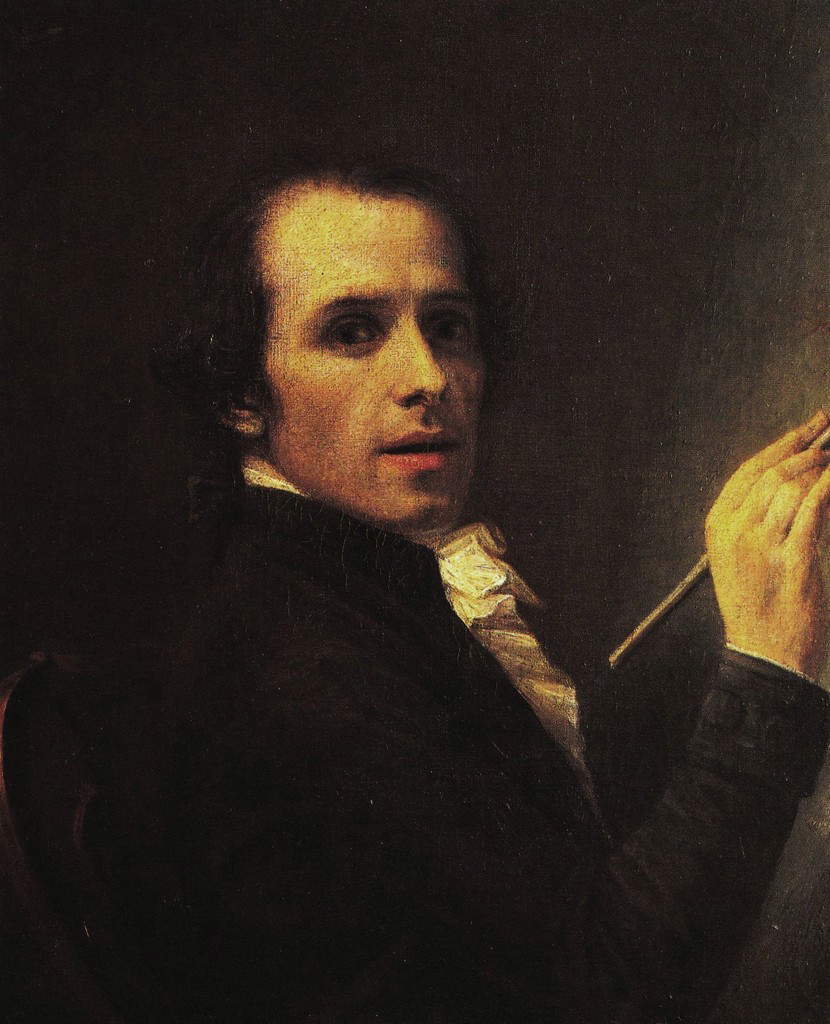

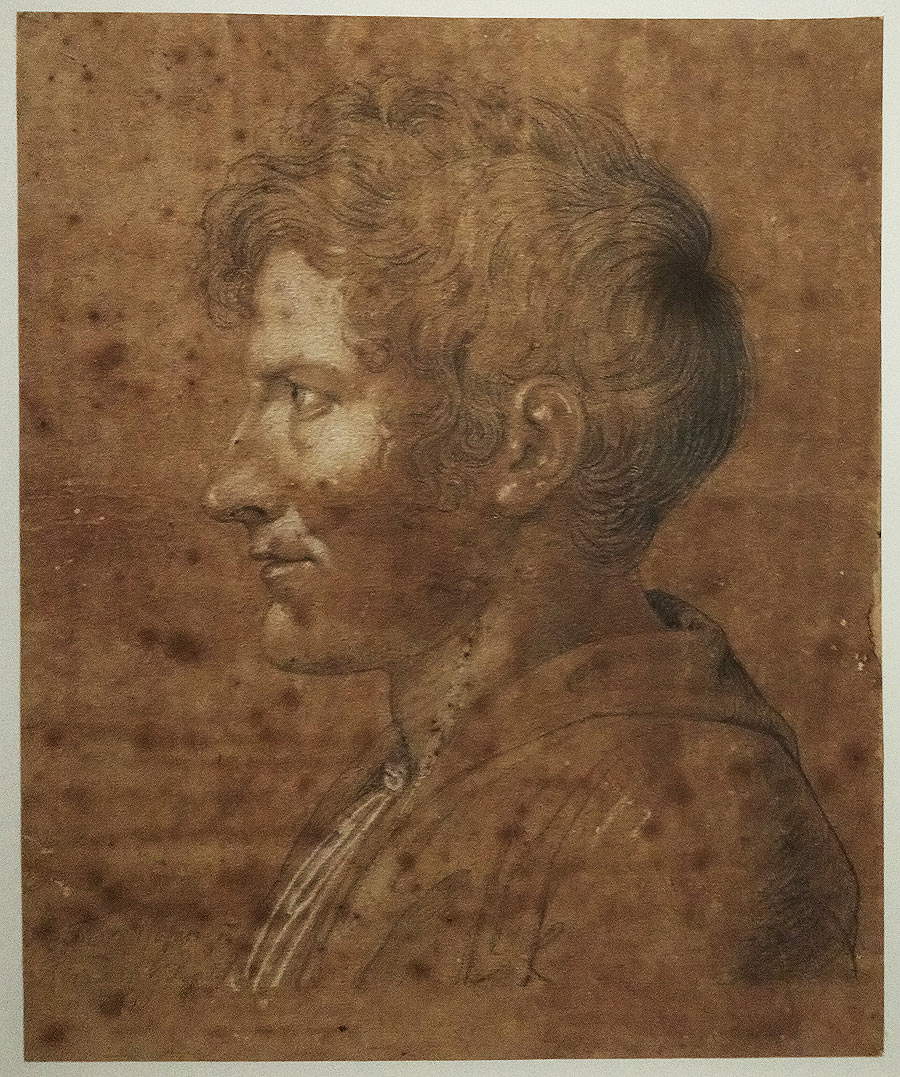

A long introibo gives the visitor a way to get acquainted with the personalities of the two sculptors. The exhibitionitinerary begins with the self-portraits, in order to immediately bring out the affinities, but even more the differences, between the two artists: here, then, is Canova in a composed youthful self-portrait as a painter, while he observes almost in amazement the relative, interrupted in a work to which the artist waits for pleasure, painting not being his main activity. His shy and reserved temperament is contrasted by that of his adversary, of a more extroverted and perhaps even more combative nature, according to what transpires from his frowning gaze in the youthful drawings, where Thorvaldsen portrays himself with disheveled hair and an expression that smacks of defiance: an image with an already romantic flavor, certainly not realistic, but useful in exalting the qualities that the sculptor attributed to himself, starting with that same determination and pride that united him with the Venetian. And on portraits, Canova and Thorvaldsen already engage in a confrontation: one of the high points of the exhibition is in the first room, where two marble self-portraits made in the same period, between 1810 and 1812, look at each other from a distance and let the public foresee the continuation of the journey and the characterizing elements of their respective ways of understanding sculpture. Canova depicts himself with his neck in a twist, mouth half-closed, eyes looking upward, an expression caught in movement: an artist who, while idealizing himself in order to consign himself to eternity, does not give up providing an image of himself with natural elements. Rigidly frontal and with a steady gaze in front of him, on the other hand, is Thorvaldsen, who, unlike his rival (a term, the latter, which Argan detested, in relation to the two: it seemed to him to immiserate the debate), pursues naturalness on the level of adherence to his own real features, but seeks a heroic and immortal dimension in the fixity and ataraxia that compete with the venustiousness and calm of the Greek herms, which the Dane certainly had in mind, even though he had never visited Greece in his life.

Instead, with the next sections we enter the artists’ everyday dimension, that of their Roman ateliers, where both Canova and Thorvaldsen were able to bring to life a totally new conception of the artist’s craft: the studio was no longer just a place of work, but also a tidy exhibition hall, a shiny showroom to be shown not only to patrons who were given the opportunity to get a glimpse of the artist’s “catalog,” but also to travelers, critics, or powerful people, as is the case in the painting by Hans Ditlev Christian Martens (Kiel, 1795 - 1864), which captures a visit by Pope Leo XII to Bertel Thorvaldsen’s large studio on the day of St. Luke, the patron saint of artists, on October 18, 1826. Large spaces, set up with the best of the production, organized almost as if they were museums (with very careful and targeted choices: works are grouped by type or genre, and the search for wonder is not disdained), suitable for the most demanding and most considerate guests. Martens’s painting certainly does not correspond to what Thorvaldsen’s studio actually looked like, but from witnesses we know that Leo XII gathered in prayer before the Savior ’s plaster cast for almost an hour, a sign that that enormous room (“which in size can be compared to a church,” wrote the erudite Just Mathias Thiele, Thorvaldsen’s compatriot and friend: he visited his studio in Rome) had hit the mark. Works capable of passing on the copious abundance and almost basilical solemnity of these ateliers, and which also had a function, we would say today, of promotion, since they were means of establishing the fame of two artists who, already in life, were surrounded by an aura that almost ascribed them to the rank of heroes.

The following rooms punctually demonstrate the consequences of the true cult that was celebrated around the two contenders: the officiants were the patrons in constant search of their works and the critics who divided over who was the greatest, while their sculptures were the relics capable of spreading this authentic veneration, hardly paid in life to other artists (not even the divine Raphael went so far), and which was able to pervade the whole of Europe. An entire room is devoted to Canova portraits executed by a vast plethora of artists, from the more conventional ones to those in which Canova was already deified in life: noteAntonio Canova’s Antonio Canova sedente in atto di abbracciare l’erma fidiaca di Giove by Giovanni Ceccarini (Rome or Fano, 1790 - Rome, 1861), which Stefano Grandesso identifies as the most ambitious of the marble portraits executed by admirers of the Venetian, celebrated here as a kind of sculpture god, capable of inaugurating modern art by giving new meaning to ancient art. The large portraits of Jacob Edvard Munch (Oslo, 1776 - 1839) and Rudolph Suhrlandt (Ludwigslust, 1781 - Schwerin, 1862) show the two artists, side by side again, at the height of their careers: they are two powerful, magniloquent portraits, recalling seventeenth-century portraiture, and whose intent is not to provide a verisimilitude description of the effigies, but to give an account of the achievements they reached and the results of their art (note, in Canova’s, the view of St. Peter’s Basilica in the background and the plaster model for the statue of Empress Maria Luigia of Habsburg as Concordia, moreover present in the exhibition and displayed alongside the painting). An interlude always connected to the theme of the glory of the two artists gathers lithographs, medals and reproductions that toured all over Europe contributing not only to the popularization of their inspiration, but even their image: and that of Thorvaldsen is exalted in a room devoted to the icons of the Dane, “idolized as the refounder of national art,” Grandesso writes, “and looked upon himself as a patron and patron, who welcomed young sculptors into his studio as collaborators or subsidized the apprenticeship of painters in the Urbe by purchasing their work.” A work that found its outcome in the Thorvaldsens Museum in Copenhagen, a very rare case of a museum devoted to a single artist opened with the dedicatee still alive. So here arrives, from Palazzo Barberini, the statue that his pupil Emil Wolff (Berlin, 1802 - Rome, 1879) wanted to erect in his honor in 1861, here is the intense portrait of the Dane executed by his friend Vincenzo Camuccini (Rome, 1771 - 1844), who restores him to us with an immediacy reminiscent of sixteenth-century portraits, and here is also a private Thorvaldsen, depicted by Ditlev Conrad Blunck (Münsterdorf, 1798 - Hamburg, 1854) together with some friends, his fellow countrymen, while having lunch in a Trastevere tavern: singular tribute, moreover institutional (it was desired by the mayor of Copenhagen), to the circle of Danes in Rome and the everyday life they frequented.

|

| Antonio Canova, Self-Portrait (1792; oil on canvas, 68 x 54.4 cm; Florence, Uffizi, inv. 1890 no. 1925) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Self-Portrait (Sept. 8, 1811; black chalk and white highlights, 275 x 227 mm; Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, Inv. C 759) |

|

| Francesco Chiarottini, Antonio Canova’s Study in Rome (c. 1785; pen drawing, gray and brown ink, watercolor in gray and brown on blue paper, 385 x 556 mm; Udine, Civici Musei, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe del Castello, Inv. 9) |

|

| Hans Ditlev Christian Martens, Pope Leo XII visits Thorvaldsen’s large studio on St. Luke’s Day, October 18, 1826 (1830; oil on canvas, 100 x 138 cm; Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst, inv. KMS196, on deposit in Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum) |

|

| Giovanni Ceccarini, Antonio Canova sedente in atto di abbracciare l’erma fidiaca di Giove (c. 1817 - 1820; marble, 188 x 107 x 155 cm; Frascati, Palazzo Comunale) |

|

| Vincenzo Camuccini, Bertel Thorvaldsen (c. 1808; oil on canvas, 100 x 80 cm; Rome, Private Collection) |

|

| Ditlev Conrad Blunck, Danish Artists at La Gensola tavern in Trastevere (1837; oil on canvas, 74.5 x 99.4 cm; Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. B199) |

The primacy of sculpture

After a further interlude devoted to works celebrating the genius of the two artists, the direct confrontation between their sculptures begins, the most eagerly awaited, eagerly awaited, surprising and exciting part of the Gallerie d’Italia exhibition: the rooms are organized in such a way that the path does not follow a univocal thread, and it is the visitor who can carve out the stages of his or her own path, to his or her taste. We propose here to begin with the hall dedicated to the portraiture of Canova and Thorvaldsen, where parallel juxtapositions already abound: it was not a genre with which they liked to measure themselves, portraiture being the one that leaves the least room for the artist’s imagination. So at least it was for Canova, who practiced it little, for few, and highly selected clients. For Thorvaldsen, on the contrary, portraiture was nonetheless a relevant genre, allowing him to express, even in the busts of his wealthy patrons, his ideals of motionless imperturbability: no emotions should convey the expressions of his characters, no feelings should disturb their nobility and elegance. To get an idea, take one of the highest achievements of Canova’s portraiture, Pope Pius VII, preserved at Versailles: the vividness of the pontiff’s expression, misaligned from the dictates of the strictest observance of neoclassicism, restores the vividness of the effigy. And similar considerations could be made for the portrait displayed next to him, the posthumous one of composer Domenico Cimarosa, where, writes Fernando Mazzocca, “observation of reality seems to take over from the usual idealization.” For an essay on Thorvaldsen’s portraiture, look at the images of the Duchess of Sagen and Metternich, displayed side by side: the Dane’s works, in this genre, always tend to strike a delicate balance between adherence to reality and idealization. If the facial features thus seek to provide the relative with a true semblance of the subject, references to classical statuary (nudity for Metternich, Severan hairstyle for Wilhelmine Biron) and the impassive detachment of the gaze, on the other hand, are the ways in which the Copenhagen sculptor manages to rescue his characters from the transience of life.

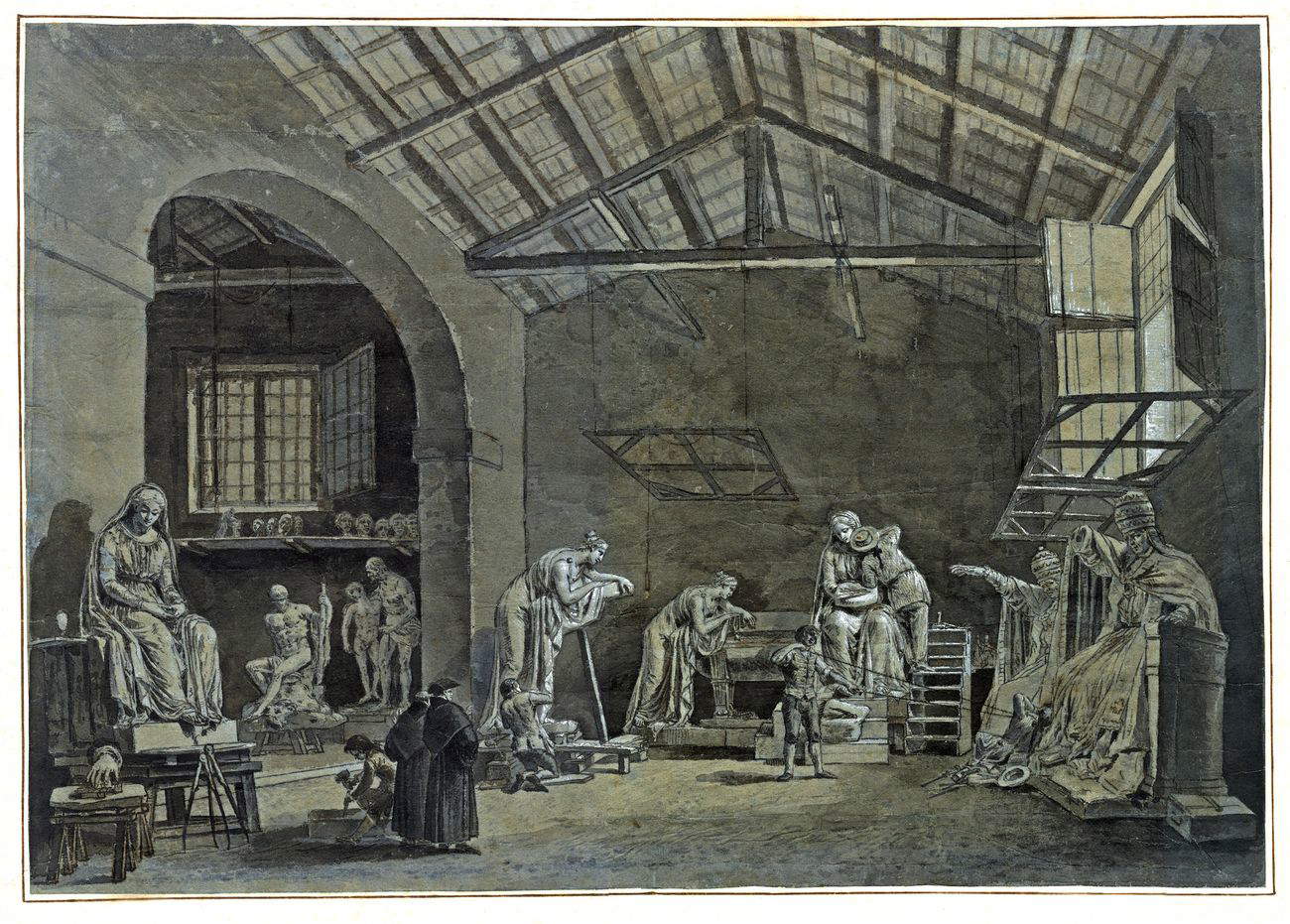

A coda to this section can be found in the next room, apparently dominated by Canova’s marvelous full-length portrait of Princess Leopoldina Esterházy Liechtenstein, stopped in a delicate, carefree youth, the result of an originality capable of updating the lofty model of the Vatican muses from which the Venetian was inspired, and such as to arouse grateful, perennial and unconditional admiration on the part of the noblewoman. All around, however, it is Thorvaldsen who holds the stage, with what many consider to be his highest masterpiece, namely the aforementioned frieze ofAlexander’s Entrance into Babylon, shown here in the reduction taken in 1822 from the model of ten years earlier and preserved in the Gipsoteca of the Civic Museums of Pavia. Relief was one of Thorvaldsen’s favorite techniques, probably because it was such for one of his mentors, his compatriot archaeologist Jörgen Zoega (Daler, 1755 Rome, 1809): the Dane was a careful scholar of the reliefs of ancient Greece, which he declined in a wide variety of themes, and sustained, Grandesso wrote in his 2010 monograph on Thorvaldsen, “by his ability to be able to reread, assimilate and translate into modern forms the innumerable cues drawn from an inexhaustible iconographic research on the figurative sources of classicism, from reliefs to cameos, gems and engraved translations.” And his continuous refinement of style came to the point that even contemporaries who considered Canova superior to him could not fail to recognize that, in relief, primacy indisputably went to the Scandinavian. And in this field, the Alexander frieze is the great, magnificent masterpiece, inspired by the Parthenon frieze, that the sculptor came to know through the engravings that circulated in early 19th-century Rome: commissioned by Napoleon, it was to decorate the Salone d’Onore at the Quirinale, evoking Napoleon’s deeds through those of Alexander the Great (the conquests and victories, valor as commander, entry into Babylon as entry into Rome). The work’s fortune reached such a pitch that Thorvaldsen was immediately asked for replicas: the one intended for the Pantheon in Paris was later purchased by Sommariva for the villa in Tremezzo after the fall of the Napoleonic empire. “Neutral background, frontal plane, parsimony of expressive means, minimalism in the settings, prevalence of line over volume, conciseness, in essence foreignness to the illusionistic tradition of the five-seventeenth century”: this is how scholar Ilaria Sgarbozza summarizes, in the full-bodied exhibition catalog, the basis of the profound Greekness of this relief. As close to Greek art as had ever been seen until then in modern art.

The various narrative digressions, in the bucolic genre (the shepherds, the fisherman), that Thorvaldsen inserts into the frieze are the best introduction for the sections that follow, in which the Dane’s statuary takes center stage. Beginning at the back of the room, the Arcadian theme is reflected in the Shepherd Boy, which had incredible fortune (as attested to by the languid works inspired by it and in many ways anticipating Romantic verve ): executed in the mid-1920s, it marked a change of pace in Thorvaldsenian sculpture, which veered from the heroism of mythological characters to the sentiment of this pastoral subject that is distinguished by the spontaneity of its pose, by the construction that evokes its absorbed meditation (perhaps, as per the topos of Arcadian literature, by an amorous disturbance), and by its unusual naturalism. For Grandesso, the Pastorello represents “the original contribution of Roman classicism to the European Romantic sensibility.”

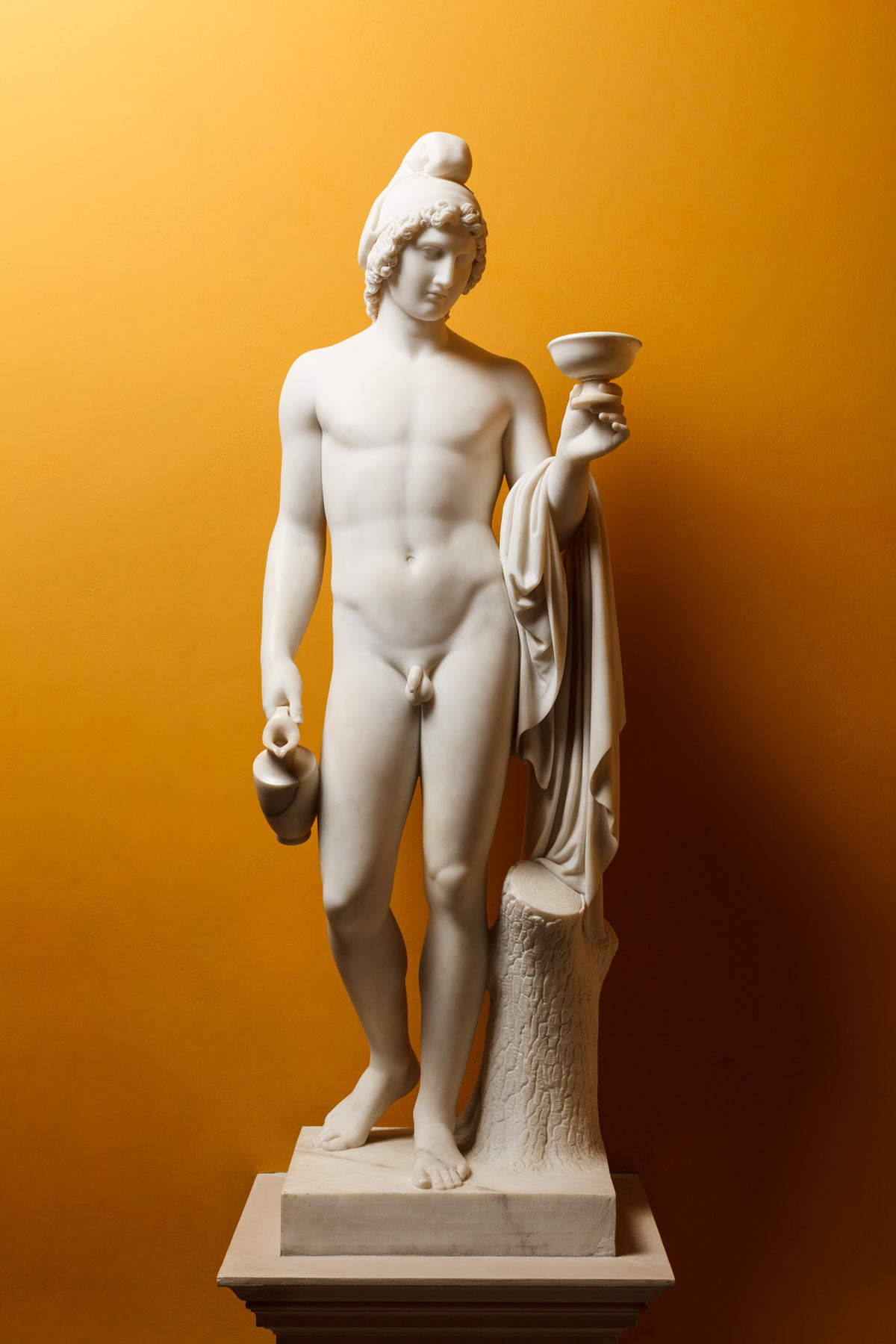

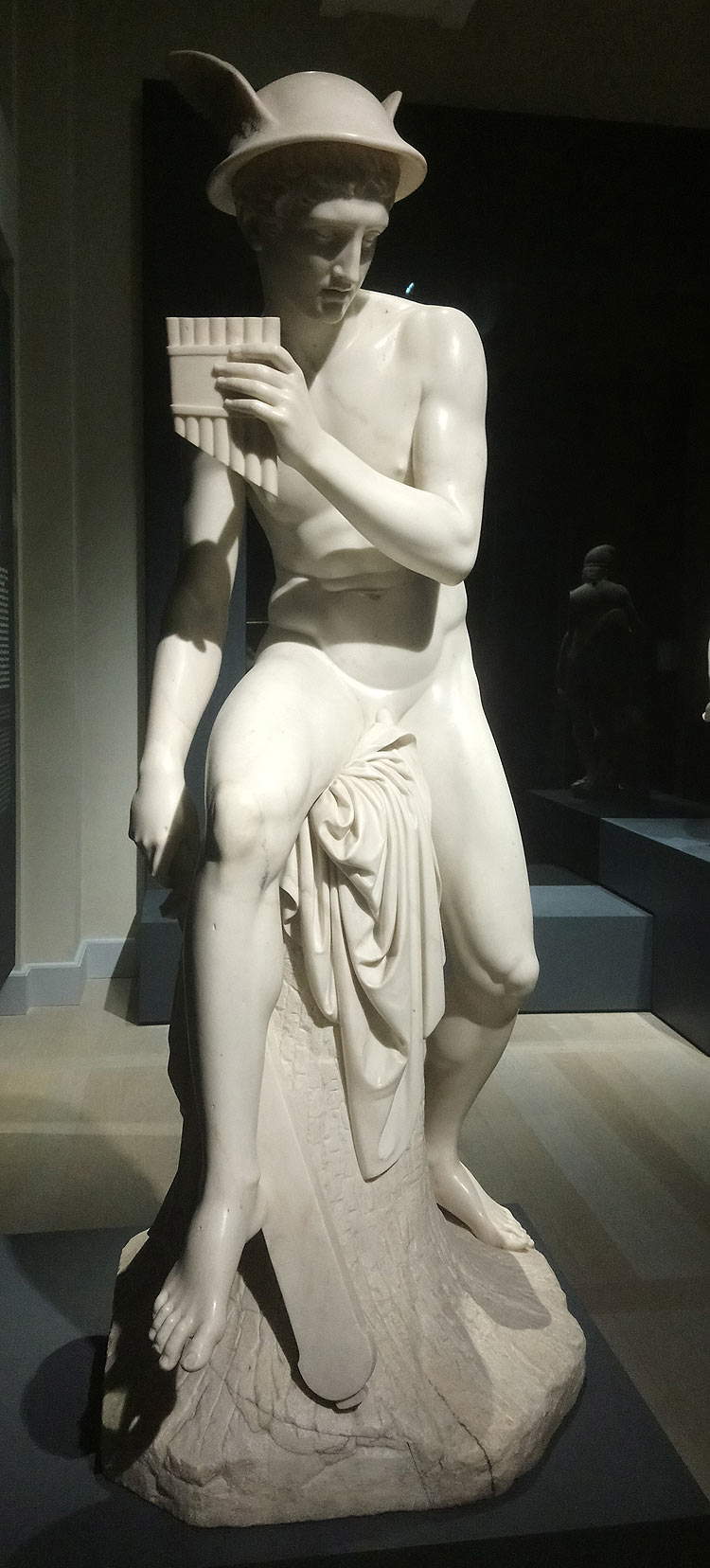

We continue backwards to arrive at the section that more than any other evokes that “Olympus” to which Thorvaldsen tried to give form throughout his career in order to experiment with an alternative model of beauty to that imposed by Canova. Wanting to respect the chronological sequence, the first work of those in the exhibition to give substance to the Thorvaldsenian pantheon is the Ganymede taken from the 1804 model: the sculptor, then 34 years old, entrusted the cupbearer of the gods, absent from Canova’s repertoire, with the task of becoming the bearer of his adherence to Winckelmann’s canon. His Ganymede presents himself to the observer in his adolescent gracefulness, his body not yet fully formed, his relaxed pose, his naive attitude, beauty as a means of establishing contact with the divine, here symbolized by the cup on which the gaze of the character from mythology is focused. This Ganymede, on loan from the Thorvaldsens Museum in Copenhagen, is on display in the exhibition paired with another Ganymede, arriving from the Hermitage, and the counterpart sculpture by Camillo Pacetti (Rome, 1758 - Milan, 1826), among the first to grasp the novelty of Thorvaldsen’s sculpture. Further inhabitants of this Olympus are the Mercury on the verge of killing Argos, a variation of the aforementioned Shepherd boy (after all, Ovid narrates in the Metamorphoses that the messenger of the gods, in order to get the giant with a hundred eyes, pretended to be a shepherd in order to tell him a story and put him to sleep with the sound of the flute, and then rage on him), another work that to some extent departs from the heroism of the Dane to present us with a god caught in the thick of an action, and the Ganymede with Jupiter’s eagle, one of the artist’s most successful inventions (the painter Luigi Basoletti, writing to Count Paolo Tosio, owner of the work, called it “a jewel of modern sculpture”), inspired by ancient glyptics, with Ganymede who, stooping, gives a drink to Jupiter who comes to him in the guise of the eagle that will later abduct him and take him to heaven.

|

| Antonio Canova, Pope Pius VII (c. 1804-1805; marble, 71 x 60 x 31 cm; Versailles, Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, inv. MV617) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Klemens von Metternich (1819; marble, 61 x 30 x 25.6 cm; Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. A234) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Wilhelmine Benigna Biron duchess of Sagan (1818; marble, 58 x 28 x 24 cm; Rome, Museo Napoleonico, inv. MN54) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Triumph of Alexander the Great in Babylon (1822, reduction from 1812 model; plaster, total size of series 55 x 1326 cm; Pavia, Musei Civici, Gipsoteca) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Triumph of Alexander the Great in Babylon (1822, reduction from 1812 model; plaster, total size of series 55 x 1326 cm; Pavia, Musei Civici, Gipsoteca) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Triumph of Alexander the Great in Babylon (1822, reduction from 1812 model; plaster, total size of series 55 x 1326 cm; Pavia, Musei Civici, Gipsoteca) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Shepherd Boy (1823-1826, from the 1817 model; marble, 149 x 103 x 58 cm; Manchester Art Gallery, inv. 1937-672) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Ganymede (c. 1822-1826, from the 1804 model; marble, 137 x 46.4 x 48.5 cm; Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. A854) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Ganymede with Jupiter’s Eagle (1814-1815; marble, 44 x 55 cm; Brescia, Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo, inv. 19) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Mercury on the Point of Killing Argos (1821-1824, from the 1818 model; marble, 175 x 67 x 83 cm; Potocki Collection in Krzeszowice, on deposit in Krakow, Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie) |

Grace and Beauty

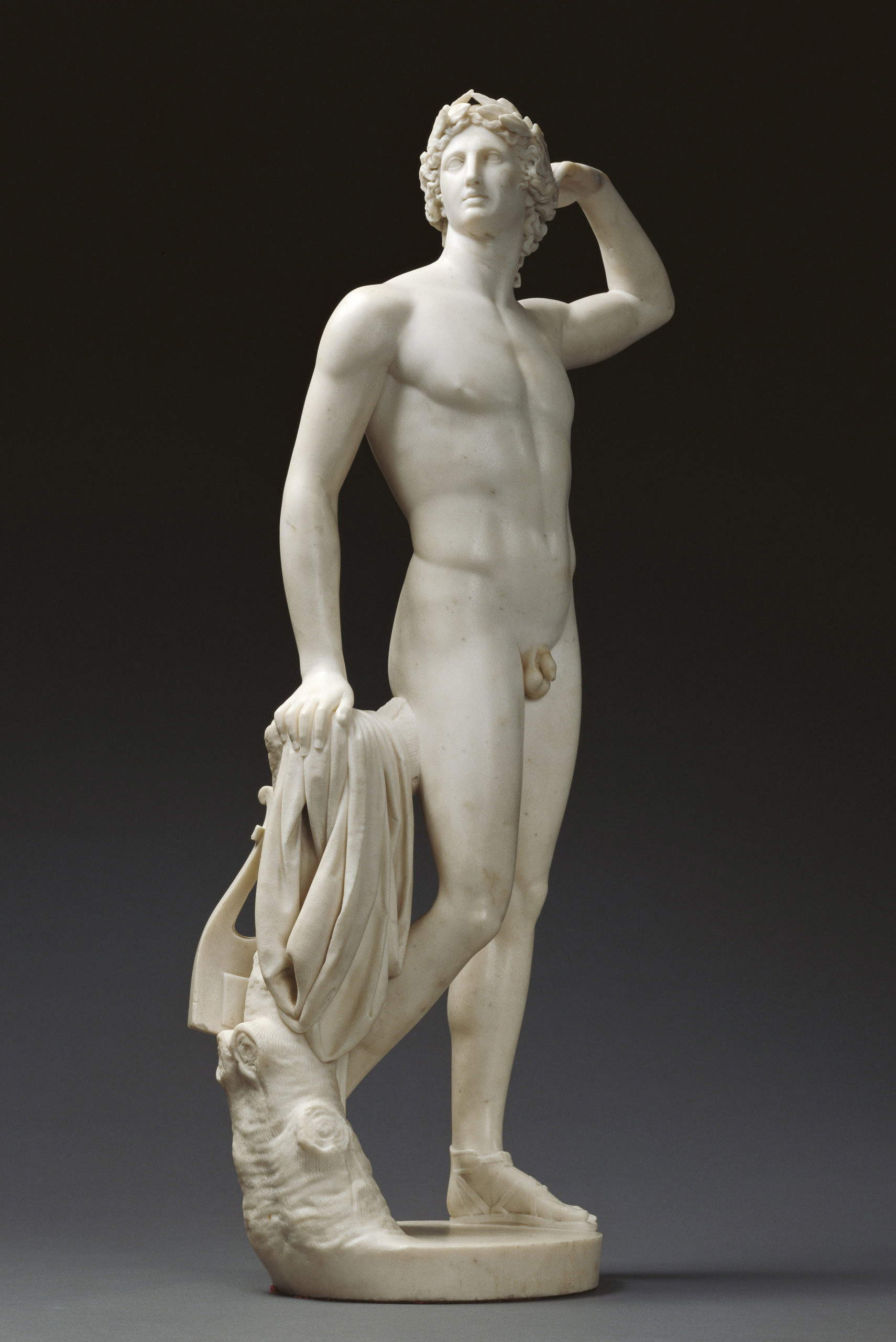

Returning to the hall devoted to portraits, we proceed to the adjoining room, wherelove is celebrated as a favorite subject of both Canova and Thorvaldsen.Apollo Crowning Himself, on loan from the Getty in Los Angeles, is one of the first creations of a barely 24-year-old Canova, as well as the first work executed in Rome, capable of blending ancient and modern in its dual inspiration from theApollino of the Uffizi, whose pose it traces, and from the Apollo that Mengs depicted at the center of his Parnassus in Cardinal Albani’s villa. Fernow, who never cultivated deep sympathies for the Venetian sculptor (far from it), while considering his Apollo crowning himself a weak work, gave him credit for having abandoned with this statue the path of nature to take that of the idea: an idea that was further perfected in theApollino of 1797, which Canova himself considered superior to all the other Amorinos and Apollinos made up to that time, and which shines out in Thorvaldsen’sLove Triumphant, which like Canova’s holds a bow in one hand but, unlike the latter, strides with outstretched wings looking at his arrow, the deity symbolizing the love that triumphs over all. On mulieval beauty, too, the two rivals manifested opposing ideas, and the comparison between the two Venuses constitutes one of the most significant passages in the Milan exhibition: Canova’s Venus is decidedly more womanly, caught in her demure covering coming out of the water, readable from several points of view, while Thorvaldsen’s is a distant and unapproachable goddess, proud of her unparalleled beauty, observing and admiring the apple that declares her the most beautiful among goddesses, eternalized according to a vision that prefers no other point of view but the frontal one.

The finale of the exhibition is centered on the theme of grace, which first permeates that fable of Cupid and Psyche that was the subject of choice for an endless list of neoclassical artists and which, as is well known, the collective imagination immediately associates with the name of Canova: at the Gallerie d’Italia, we pause before his Cupid and Psyche standing, which arrives from the Hermitage, in the version executed for the English colonel John Campbell and then purchased by Joséphine de Beauharnais. The two characters in Apuleius’ fable are two self-conscious lovers (note the delicate sensuality of the embrace, with Cupid languidly surrendering his head to his beloved’s shoulder), whose attention is caught by the butterfly (a symbol of the soul, psyché in Greek, which allows one to rise to the feeling of love): for Thorvaldsen, Cupid and Psyche are instead two adolescents who join in a naive embrace as they gaze at the vase at the center of the myth (it would have caused Psyche’s fainting and mortal sleep: Cupid would have awakened her with a kiss, in the moment captured by Canova in his masterpiece in which the two lovers lie). Variations of the theme in painting (alternating, on the walls, paintings by Giani, Gerard and Comerio) are vivid witnesses to the subject’s fortune, while the more daring sculptural groups on the same theme by Johan Tobias Sergel and Giovanni Maria Benzoni, with the latter’s Love almost soaring, introduce a further confrontation, which is played out on the figure of Hebe, handmaiden of the gods.

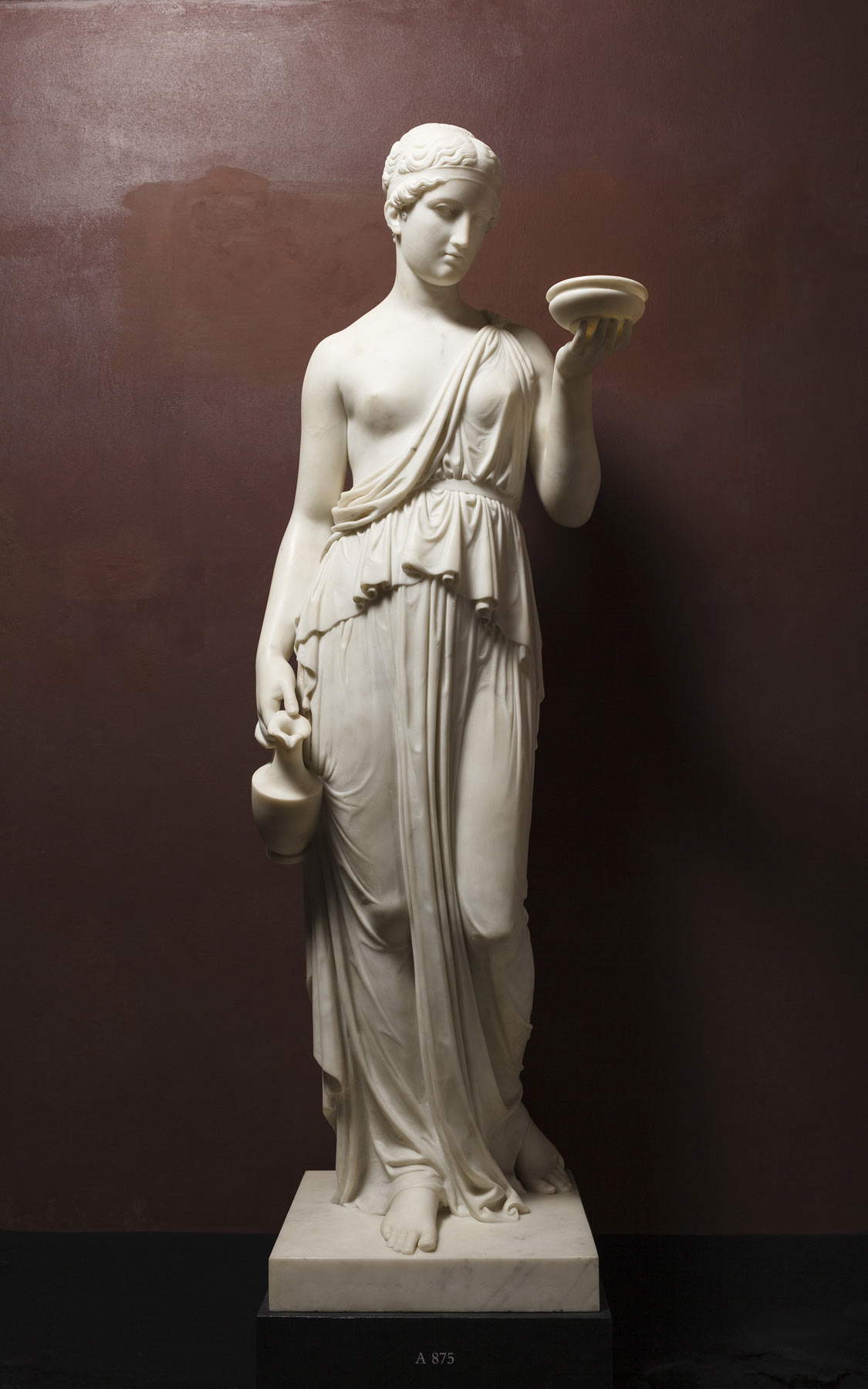

The divine maiden is the subject of one of Canova’s happiest inventions: she is perhaps the most dynamic figure in the Venetian sculptor’s production, caught as she soars on a cloud (despite being depicted without wings) advancing with her left leg, her robe reaching up to breast height and being slightly moved by the wind, and as, with her fingertips, she holds the jug and cup, gently lifting her right arm at an angle to pour the nectar, in a gesture that is unnatural but filled with graceful vagueness. Although this insistence by Canova on movement went against the wishes of the most staunch advocates of neoclassical purity (Fernow, in particular, believed that Canova’s dynamism was a Baroque legacy), so much so that it drew him harsh criticism (which also focused on the heterogeneity of the materials: he disliked the use of bronze for the cup and jug), his Hebe also received enthusiastic comments: Isabella Teotochi Albrizzi, who wrote a collection of descriptions of Antonio Canova’s Works of Sculpture and Plastics, went so far as to assert that “nor happier than here did Canova ever seem to me elsewhere with that marvelous artifice of his, with which he knows how to make his work soft, soft, and to the true color, and to the almost living motion of the flesh similissimo.” Of a different tenor is Thorvaldsen’s nearby Hebe, who seems almost to give form with marble to the contempt that invested Canova: her cupbearer seems almost a Greek kore, severe in her classical frontal pose, almost haughty in her unalterable gaze.

On the “gentle” genre is set the last confrontation, that of the central hall, where the much-praised Graces of Canova and Thorvaldsen can be exhibited side by side for the first time, after having been the subject of passionate parallels in literature. They are introduced here by a number of superb figures (Canova’s Dancer, Thorvaldsen’s, Gaetano Matteo Monti’s Tersicore, and Pietro Tenerani’s Flora ) to create a harmonious and graceful choreography that leads the audience to the center of the room, where the groups from which perhaps the two rival sculptors’ ideal of beauty emerges most clearly face each other. Canova’s Graces are three sensual women who unite in a tight embrace, bordering on lasciviousness, caressing each other, brushing their cheeks, not giving their backs to the relative as the more traditional iconography wanted, letting a soft sensuality shine through their movements. A chaste nudity, on the other hand, is what Thorvaldsen’s Graces display: Canova’s eroticism is here diluted in a pure beauty that inspires love, affection, an absence of passions to disturb the soul. Thorvaldsen’s sentiment is best explicated by the insertion of the figure of Cupid, seated at the feet of the Graces, and it emerges with palpable evidence from the attitude of his goddesses, who gather in an almost symmetrical pattern, and lap at each other’s flesh in a costumed, sober, almost chastened manner. Two opposite ways of understanding beauty: alive, human, trembling, mellifluous and persuasive Canova’s; divine, pure, unattainable, abstract, undaunted Thorvaldsen’s.

|

| Antonio Canova, Apollo Crowning Himself (1781-1782; marble, 84.7 x 51.9 x 26.4 cm; Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, inv. 95.SA.71) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Triumphant Love (1814-1822; marble, height 137 cm; Vienna, Wien Museum, inv. 250056, on deposit at the Wiener Rathaus) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Venus (1817-1820; marble, 117 x 52 x 70 cm; Leeds, Leeds Art Gallery, inv. LEEAG.sc.1959.0021.003) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Venus Victrix (1805-1809; marble, 130 x 50 x 47 cm; Kaunas, Nacionalinis Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionio dailes muziejus, inv. ČDM Ms 67) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Cupid and Psyche (1800-1803; marble, 150 x 49.5 x 60 cm; St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv. 17) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Cupid and Psyche (executed in 1861 by Georg Christian Freund under the supervision of Herman Wilhelm Bissen from the original 1807 model; marble, 135 x 66.6 x 42.7 cm; Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. A27) |

|

| Giovanni Maria Benzoni, Amore e Psiche (1845; marble, 163 x 102 x 50 cm; Milan, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, inv. GAM 1644) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Hebe (1800-1805; marble, 161 x 49 x 53.5 cm; St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv. 16) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Hebe (c. 1815; from plaster model of 1806-1807; marble, 156.5 x 51.2 x 59.5 cm; Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. A875) |

|

| Antonio Canova, The Three Graces (1812-1817; marble, 182 x 103 x 46 cm; St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv. 506) |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, The Graces with Cupid (1820-1823, from the 1817-1819 model; marble, 172.7 x 119.5 x 65.3 cm; Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum, inv. A894) |

The birth of modern sculpture

It can be said without fear of contradiction that the line drawn by Canova and immediately followed by Thorvaldsen (who was with him the first to share it) is one of the great watersheds in art history. Mazzocca recalls that Cicognara identified Canova as the initiator of the “happy revolution in the arts”: there was therefore sculpture before Canova and Thorvaldsen, and sculpture after them. The modern organization of artists’ studios is rooted in their practice: the master who traces the idea on paper, the stonemasons who take care of roughing out the block and leading the work to the final stages, and again the master who gives “the last hand” to the sculpture. A practice that allowed their works to be replicated several times, so that their name traveled everywhere along with the sculptures. No other artist in his lifetime enjoyed the honors that were bestowed on Canova and Thorvaldsen. No one before them had achieved a similar level of independence-another element that makes them comparable to the artists of today. Both were aware that the coveted ancient age would never return, and as a result the ancient, in their art, is tinged with nostalgia and at the same time declined according to the sensibilities of two men perfectly cast in their contemporaneity: one thinks of the virtues of the patrons that Canova wanted to bring out by transfiguring his subjects into the characters of mythology; one thinks of how the monuments of one and the other had inserted themselves into the debate between the Classics and the Romantics, who understood in antithetical terms the role of public statuary (for the Classics it counted the exaltation of the single virtue to be decanted with the form of allegory, and the Romantics on the contrary emphasized the need to focus on the recognizable gesture, the feat, the tangible example to be imitated), consider how they both interpreted the civic role of sculpture on which the intellectuals of the time insisted.

And above all, at the apex of a very high level, rigorous path, with excellent loans, which touches these elements evoking them through a continuous and engaging comparison, lies the disruptive force of a dualism that is renewed between admirers of one and detractors of the other, that moved critics to passion, who sided with Canova or with Thorvaldsen, creating two opposing factions that fueled the rivalry and the debate that ensued, and still surprises those who continue to admire, two centuries later, the works of these two great artists. An antagonism that was well oiled by critics contemporary with them, but from which even today’s observer does not escape: it is difficult to escape the temptation to compare the personalities of Canova and Thorvaldsen. And both probably benefited from this climate of rivalry, although at the official level relations were cordial and relaxed. Of course, there is no need to see the careers of the two artists as always parallel and conducted in response to each other’s: the autonomy of their paths emerges clearly from the Gallerie d’Italia exhibition. Only, it likes to think that the competition may have acted as a goad to spur the two artists on to continual improvement. And it was perhaps a similar awareness, more or less felt, that generated some of the greatest masterpieces in art history.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.