Brazil as told by Candido Portinari in exhibition at Palazzo Pamphilj in Piazza Navona

A large canvas takes up almost an entire wall: dark colors, which dominate the painting, provide a backdrop for people whose faces are not highlighted, as if to signify the equality and parity between them. The people represent the only point of light in the entire painting. A man, whose face is the only one we clearly distinguish in the painting, is placed on the right; he is characterized by a strong, muscular build, and his face appears disproportionate to his body. His features are quite pronounced: closed, almond-shaped eyes, a dark mouth with protruding, fleshy lips; on his head a straw hat and in his hands a large bucket. On the left of the painting, a seated figure of a woman in profile looks toward the center of the work, where two men appear in the very foreground, each holding a large sack on their shoulders and heads with muscular arms. The figures distributed in the painting are performing various actions: some are introducing their hands into sacks filled with coffee beans, others are carrying huge sacks on their backs, one figure is climbing a palm tree, another is climbing a ladder, and in the distance predominantly female figures are intent on harvesting coffee from rows placed next to each other. All actions that belong to a single purpose: harvesting on coffee plantations. The only character that differs from all the others and is placed on the left side of the painting is a man with a black wide-brimmed hat, wearing a pair of boots that are also black (as opposed to all the other characters, who move barefoot) and who points to the workers with a gesture of command.

Coffee, from 1935, is a work that attracts the visitor’s curiosity as soon as he crosses the threshold of Palazzo Pamphilj, more precisely of the Candido Portinari Gallery in Rome’s central Piazza Navona, both because of its size and because of the particularity and specificity of the theme depicted, a theme that is moreover very common in the art ofLatin America. In particular, recall the gigantic murals created by Diego Rivera dedicated to the history, culture and traditions of his country, Mexico.

|

| Candido Portinari, Café (1935; oil on canvas, 130 x 195.4 cm; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

|

| Candido Portinari, Coffee, detail |

|

| Candido Portinari, Coffee, detail |

Coffee does not depict Mexico, but Brazil, the native land of Candido Portinari (Brodowski, 1903 - Rio de Janeiro, 1962), to whom the Palace, now home to the Brazilian Embassy, has dedicated the exhibition Portinari. The Endless Hand, which will close on April 22, 2017.

It is no coincidence that the name of the Gallery hosting the exhibition and the name of the artist author of the works on display coincide: on October 15, 1962, the Candido Portinari Gallery was inaugurated as an exhibition space reserved for temporary exhibitions of Brazilian art, following the acquisition two years earlier of the Pamphilj Palace by the Brazilian government, and the naming of one of the most important artists in the history of art in Brazil, namely Portinari, was intended as a tribute in his regard after his death in February 1962. And still today, fifty-five years after that inauguration, the Portinari Gallery has decided to pay homage again to the artist to whom it owes its name.

|

| Entrance to the exhibition Portinari. The Endless Hand |

|

| One of the two rooms of the exhibition |

Another aspect that is immediately noticeable is the artist’s surname, which makes manifest his Italian origins: his parents were in fact from Veneto, but they emigrated to Brazil, where their son Candido was born in 1903, and worked on coffee plantations in the hinterland of the state of São Paulo. Those same plantations he depicted in his great masterpiece, with which in 1935 he represented Brazil during theInternational Exhibition of Modern Art at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh and which earned him an honorable mention.

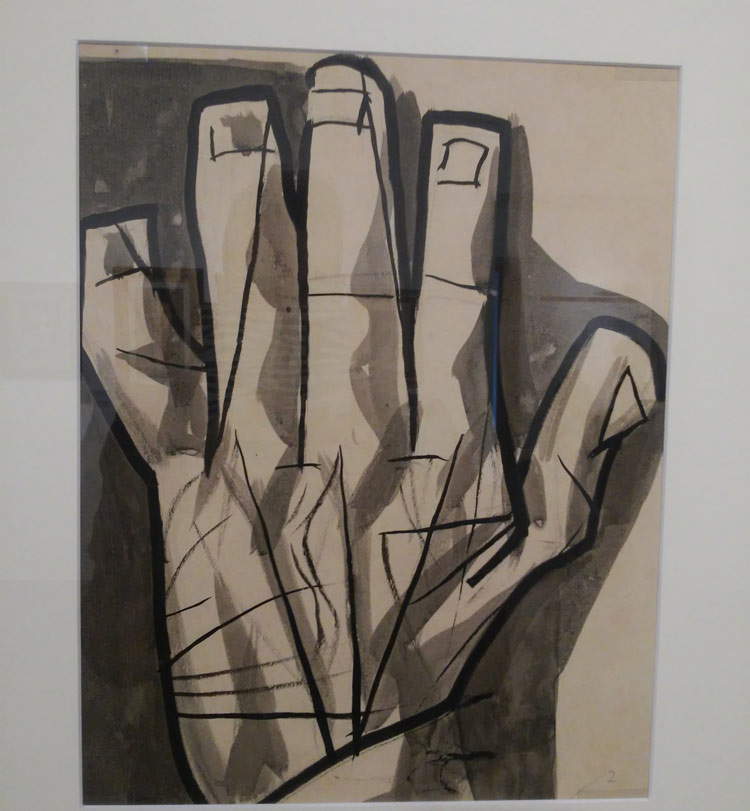

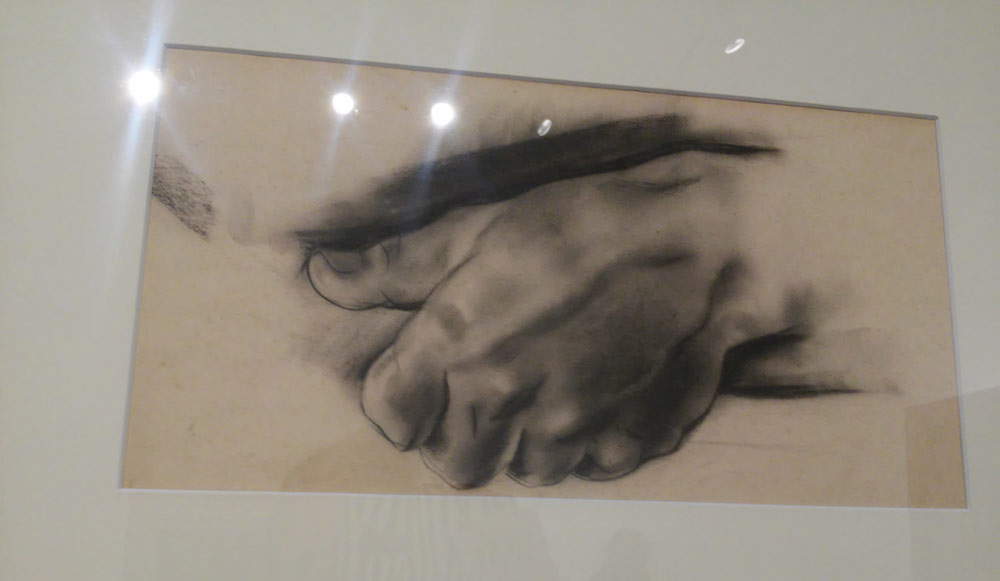

Curated by art historians from the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes in Rio de Janeiro, where all the works on display in Candido Portinari. The Endless Hand, the exhibition spans two rooms full of hand drawings by the Brazilian artist, allowing visitors to learn about and dwell on details and details that are part of Portinari’s most important works. Examples are the studies of hands and feet for the tile mural St. Francis of Assisi (1944) or the mural Garimpo - gold mine (1937). Because preparatory studies are fundamental to him: he received academic training at the National School of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, where he studied painting and drawing, and he well remembered the masterpieces of Italian artists, first and foremost Piero della Francesca, whom he had been able to admire during a two-year trip to Italy. His works therefore reflect his dual Brazilian and Italian identity, his deep connection with Brazil and Italy. Characteristic of Brazil are the dark, earthy colors and themes of the depiction of the Brazilian people, while from Italy comes the recurrence of Renaissance concepts, such as the importance of study and drawing. The latter were basic to the creation of a series of wall panels depicting Brazil’s economic cycles in Brazil’s Ministry of Education and Culture building.

|

| Candido Portinari, Hand Study for the tile mural Saint Francis of Assisi (1944; India ink and watercolor on paper, 25.9 x 24.7 cm; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

|

| Candido Portinari, Hand Study for the mural Garimpo (“Gold Mine”) from the Economic Cycles series (1937; charcoal on paper, 23 x 37.7 cm; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

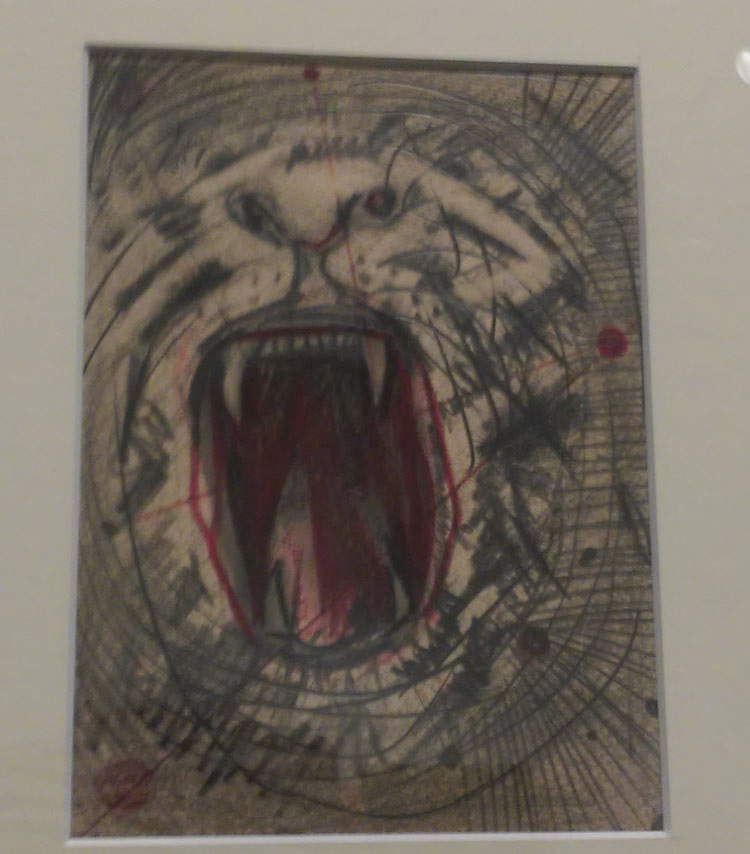

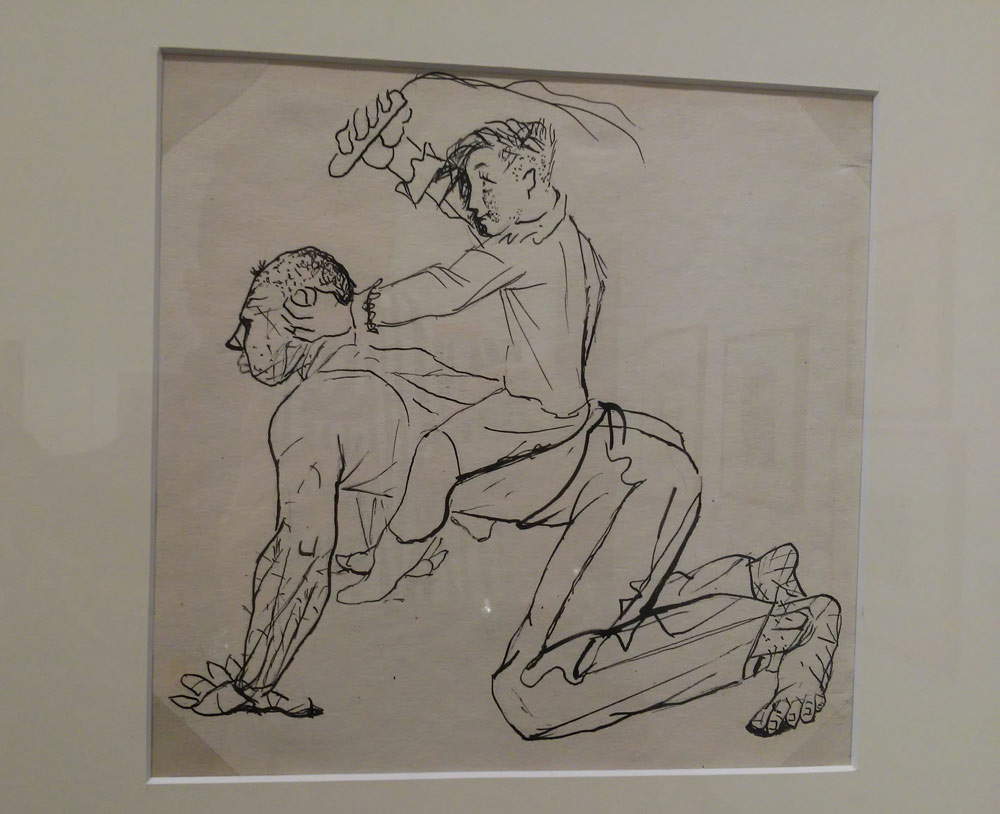

His profound interest in drawing is also documented in the exhibition by studies for the two large panels War and Peace for the United Nations headquarters in New York, including the fair study for the mural War (1955), where a gaping feline mouth from which sharp teeth emerge and the predominant colors red, black and white refer to the ferocity of war. Also: a study for the illustration of the Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas (1943), a novel by Brazilian writer Machado de Assis, which depicts a child playing horse on a man. This is not the only example of illustration for novels: Portinari also worked on illustrations for Machado de Assis’ The Alienist and the Brazilian edition of Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote de la Mancha.

|

| Candido Portinari, Fair Study for the mural Guerra (1955; graphite and sanguine on paper, 15 x 11 cm; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

|

| Candido Portinari, Study for illustration of the book Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas by Machado de Assis (1943; India ink on paper, 19 x 20 cm; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

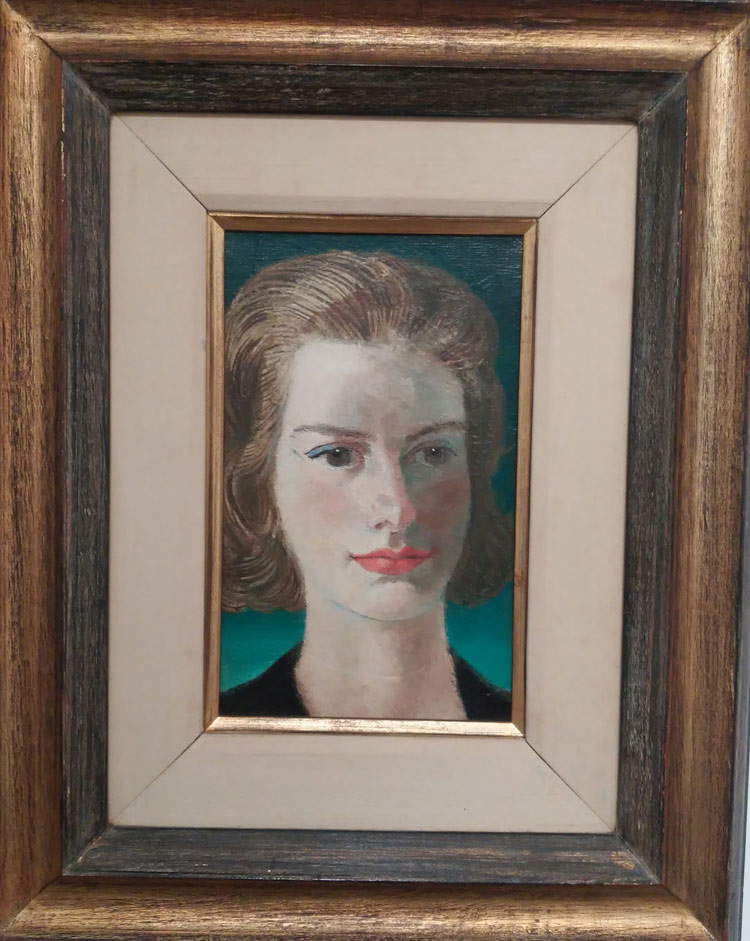

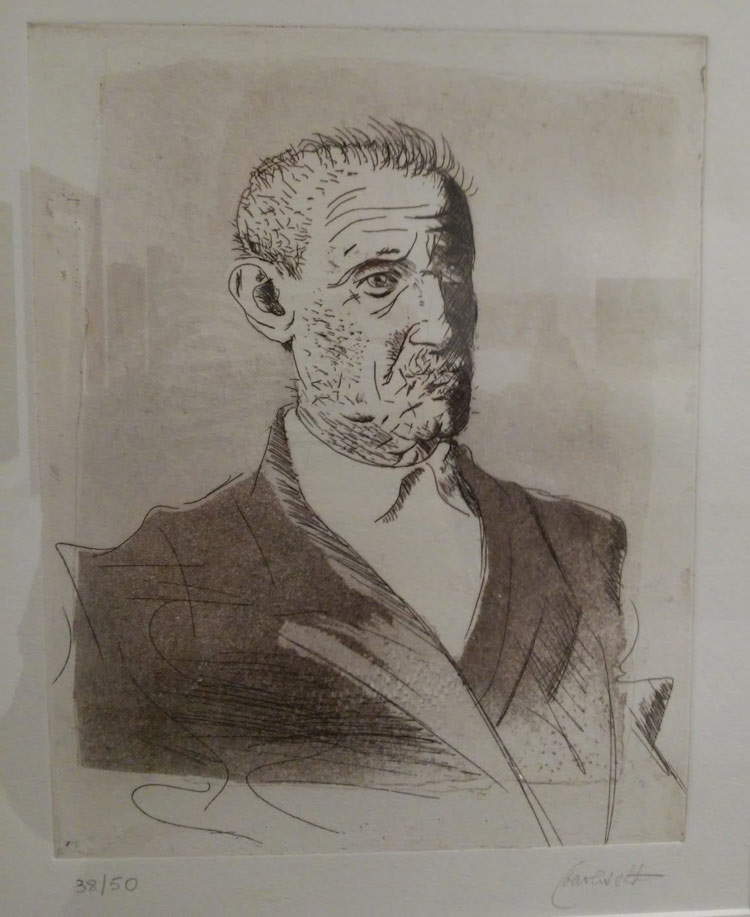

Even in the portraits of Lélio Landucci (1932), Darclée Gama Rodrigues (1959), Thais de Mello Lima (1956-59), as well as in the portrait of Baptista Portinari (1941), the artist’s father, marked strokes sharply delineate the contours of the figures, highlighting the main prerogative of his way of making art. His artistic language dominates this exhibition, which, despite its small size, leads the visitor to the knowledge of an artist who made his works universal, dialoguing with all humanity.

|

| Candido Portinari, Portrait of Lélio Landucci (1932; oil on canvas, 58.2 x 36.5 cm; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

|

| Candido Portinari, Portrait of Darclée Gama Rodrigues (circa 1959; oil on canvas; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

|

| Candido Portinari, Study for Portrait of Thais de Mello (1956-1959; oil on canvas, 30 x 18.8 cm; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

|

| Candido Portinari, Portrait of Baptista Portinari (1941; etching and aquatint on paper, 24.5 x 19.5 cm; Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.