“We would like Claude Monet to take us to Giverny, on the banks of the Seine, to that elbow of the river that barely lets us glimpse through the morning mist.” It was June 15, 1905: writing On Reading, Marcel Proust. A memory, a fragment of light glimpsed in a Claude Monet painting that leaves, in one of the greatest writers of all time, a trace in color, blurred, evanescent: the river still dozing in the dreams of the morning mist. Proust’s magical, visionary writing counterpoints Monet’s (evocative) painting, two beacons that have dazzled cultural history.

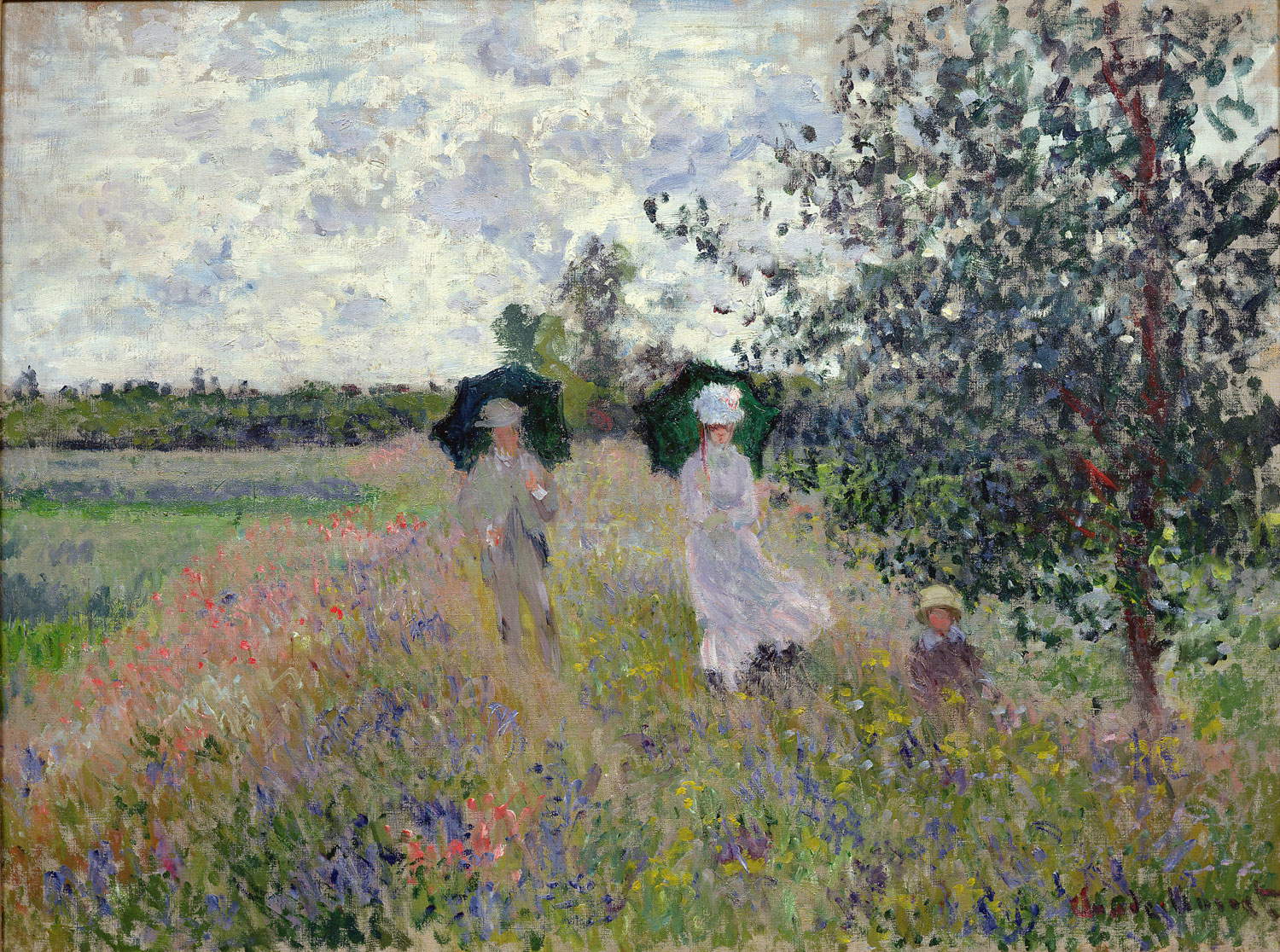

Tackling the “monster,” writing about Monet, is as far-fetched and certainly unsuccessful an undertaking as ever. Floridium of critics and art historians, intellectuals of all times have tried their hand at the feat... nevertheless, beyond the presumption of innocence for yet another attempt, what we can see is that Monet, like a few others, (Caravaggio, Van Gogh), and for different reasons, keeps us awake, still. And so it is fair to ask the question of questions: why still exhibitions on Monet? Or rather, why still Monet? Beyond the “inverted canon” of his moving, sonorous painting, there is for us also a dramatic, highly topical need, which has the name of solastalgia (an etymon recently coined by philosopher Glenn Albrecht): that feeling of nostalgia that one experiences when faced with changes in a violated, destroyed, irretrievably lost environment. The convulsive nature of our contemporary times is not comparable to the historical, cultural and environmental context of Monet’s years: however, we know what impact the two industrial revolutions and the post-Enlightenment recusal of rationalism had on art and its function. It could be argued that the first outcomes, explained very cursorily, were also the blossoming of that Romanticism that was hunting for the “sublime,” and to continue, the invention and technical achievements of synthetic colors (first and foremost, indigo) that together with photography constituted the test-bed of the Impressionists’ revolution of the gaze.

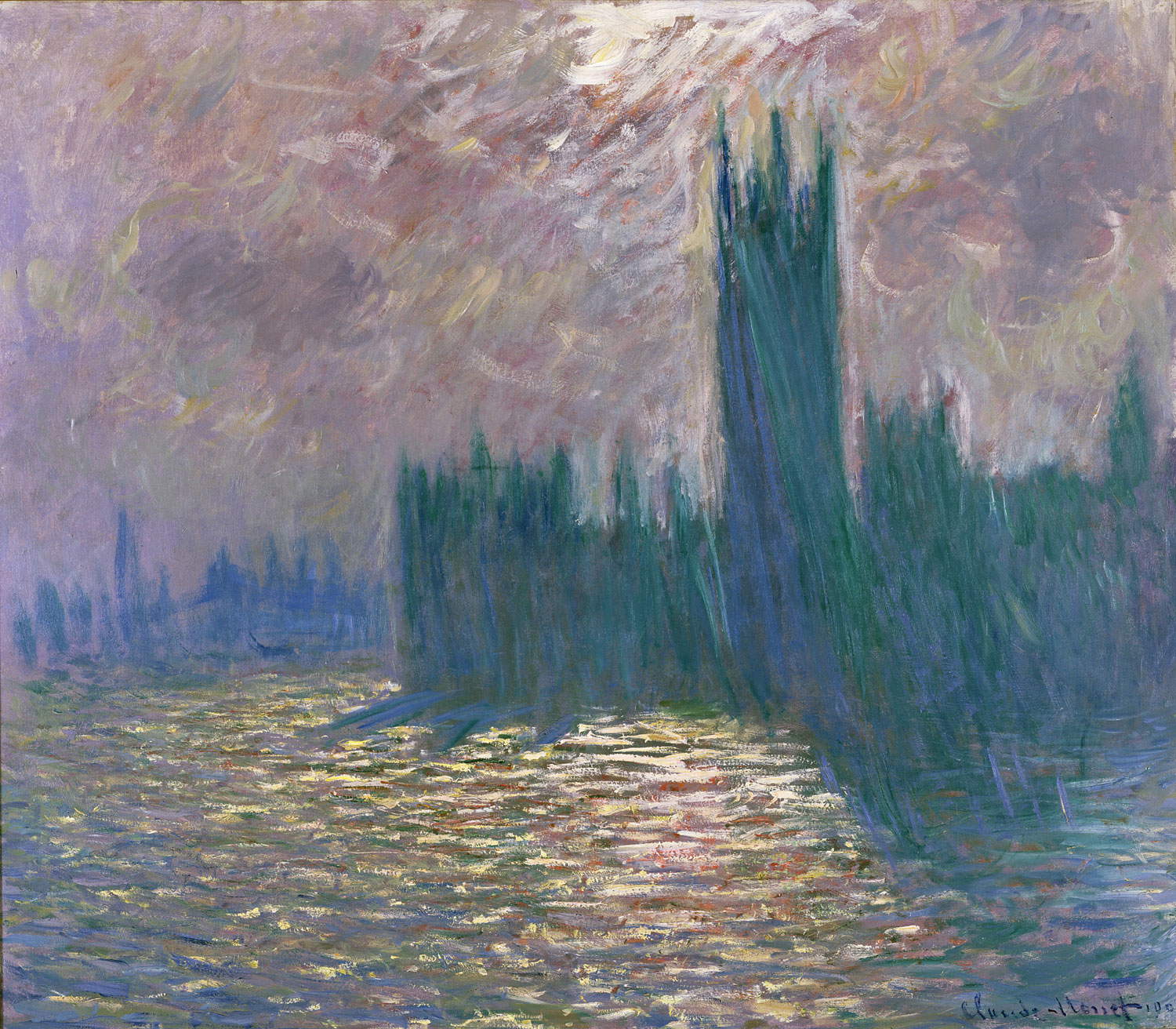

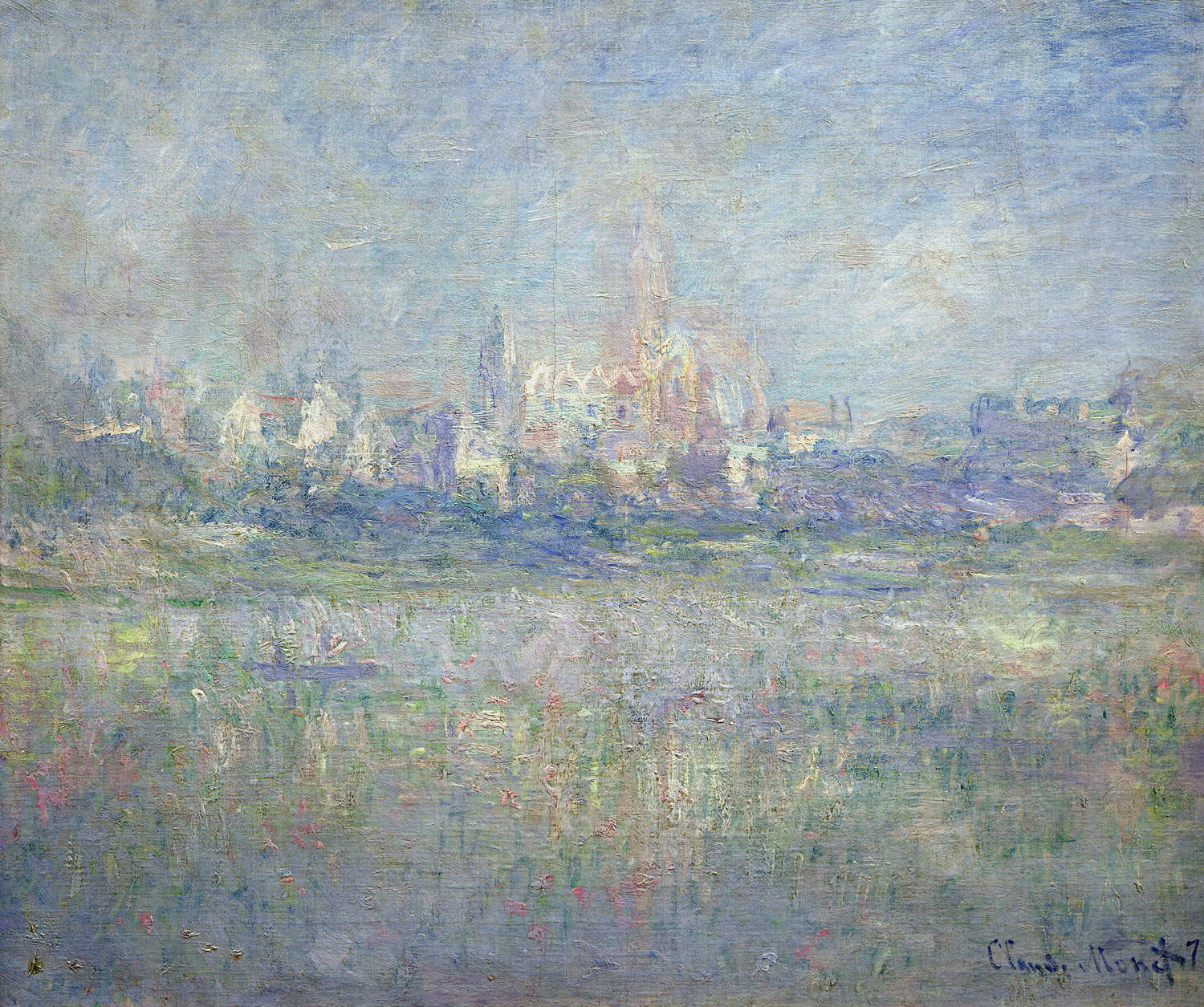

One of the aspirations of these artists, on the scene since the 1870s, even to initially rival the early daguerreotypes, was to intercept the wind (wind is said nenufar in Egyptian, and was the technical name for water lilies before Monet, yes indeed he, took on the other noun), to trap light, to grasp movement. Achieved through the use of new devices and more varied experiments, which often consisted of noting the flow of things, or an obsessive search that converged and produced the repetitions and series. Almost a pop mode! Which then mutated and translated, throughout Monet’s nearly ninety years (1840-1926), into fading, rarefaction and, ultimately, abstraction.

Contemporary Monet. Monet, the standard-bearer of many “movements” that developed later, was undoubtedly the progenitor of the constant use of repetition in painting, although in some ways, some precedents can be discerned in other painters, including Constable for example, who in his study of the same landscape, even noted the date, time and direction of the wind in his notebook!

The many phases of the painter’s long career are already being accounted for in an exhibition in Milan, through a substantial number of loans (fifty-three, all from the collection of the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris), including works by the masters, Johan B. Jongkind, Eugène Boudin, and a couple of objects: one of his palettes and the glasses with slightly yellow lenses that he had to use since 1912 because of cataracts, the same ones that dazzled his eyesight: “I no longer perceived colors with the same intensity, the reds appeared clouded to me.”

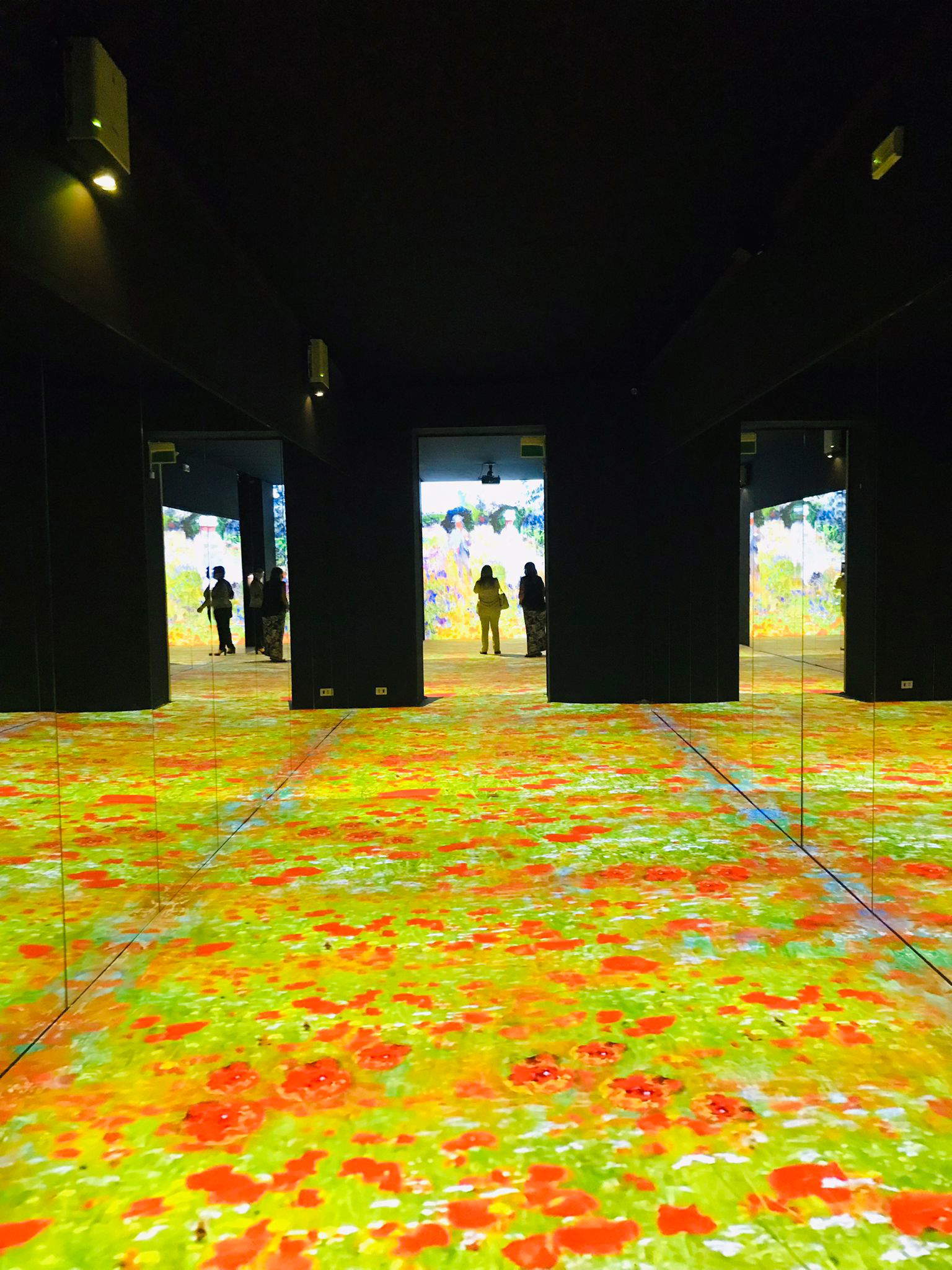

In the exhibition curated by Marianne Mathieu with Aurélie Gavoille, produced by the City of Milan and Arthemisia, laid out in the elegant spaces of the Palazzo Reale, whose only drawback is that it did not have the availability of larger rooms large ones to set up oversized immersive experiences that Monet’s wall-works, mega-environmental installations would have required, Monet’s universe is given as an ever-changing “equivocation of reflections,” as an obsession with constant change, with the perennial metamorphoses that take place “on the eternal, flowing web of time” (Giuliana Giulietti).

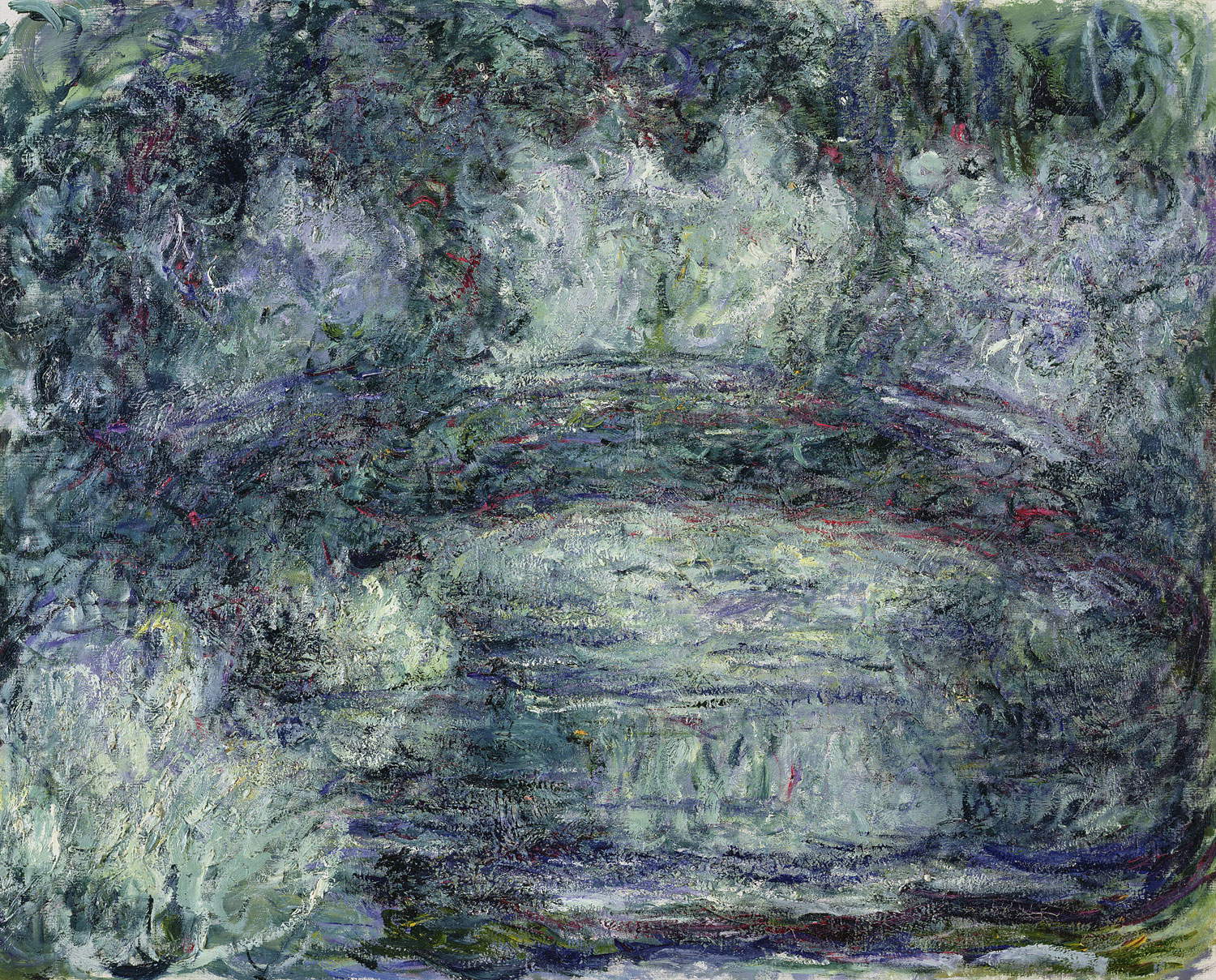

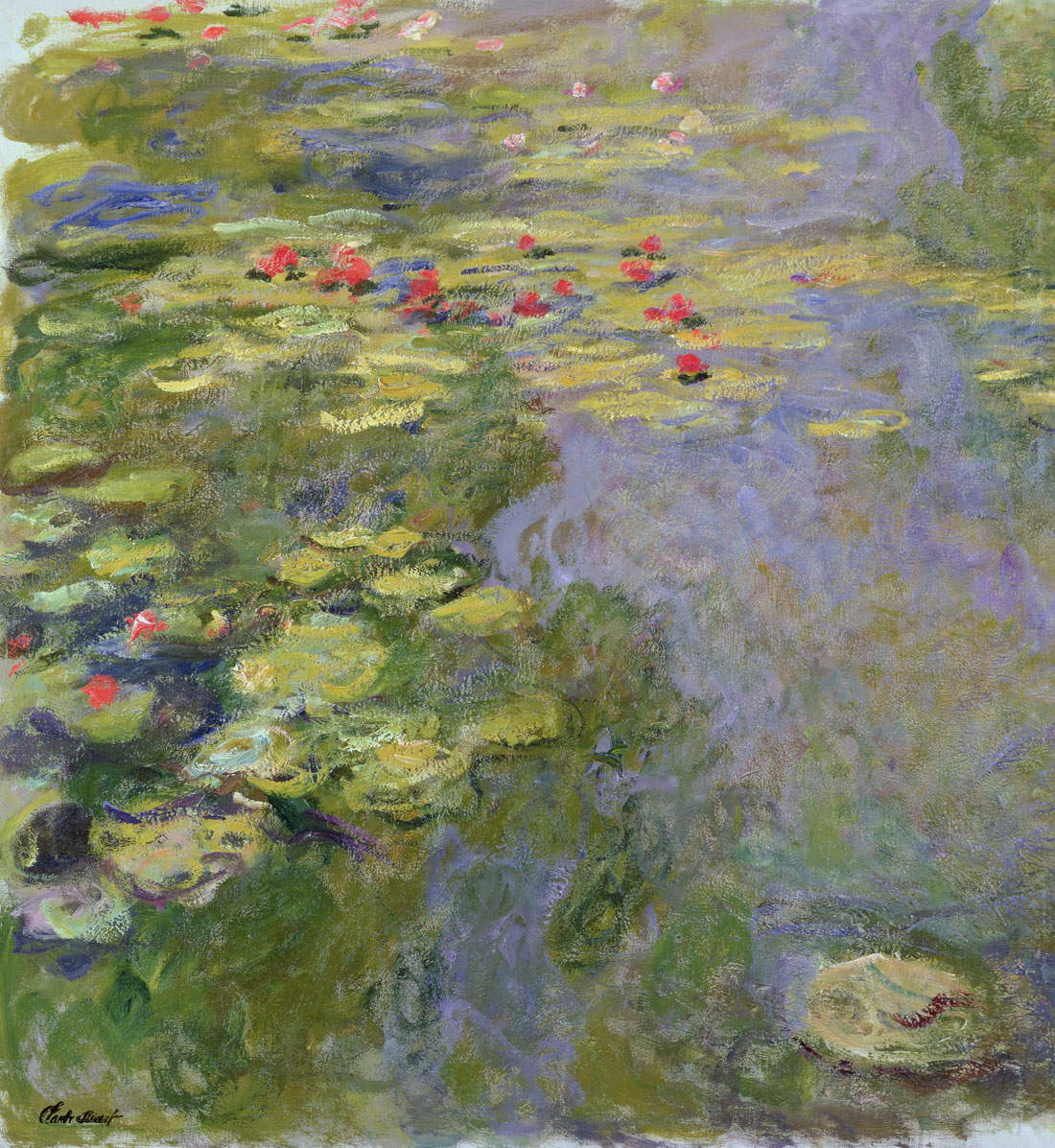

Why, which of the many Monets is on display? What phases of his continually experimental artistic research are on display? The Monet of water lilies and Japanese bridges? Or the Monet of the urban landscape, or again, the Monet at Argenteuil, or the unrecognizable one of his last years, at Giverny when, as Clement Greenberg, (the American critic and advocate of abstract art) wrote, in his painting, “light dematerializes things, crumbles them.” There are many periods, perhaps there is all of Monet, from the early works and born on the wake of realist painting, to the more modern ones, in which one gets lost and immersed, because of an absolute lack of spatial references. Among the latter, and the most fascinating, are the Water Lilies of 1916-19, the two Avenues of Roses of 1920-22, and the Japanese Bridges series painted between 1918 and 1924 (“violent impetus in applying color”: Claire Gooden, in the catalog), each of which was made without precise binocular perception and thus without any depth.

The Milan exhibition also exhibits some fascinating new hypotheses, with comparisons to at least one of the previous exhibitions, particularly the 2010 exhibition, Claude Monet 1840-1926 at the Grand Palais, in which it was argued how much further changement de pas for the abstract evolution of the late Monet, is glimpsed before when he loses in 1912 and then (with an operation ten years later) recovers his sight. There is already “an immaterial effect [...] very different from the naturalistic rendering of the colors of the place and the reflections of light characteristic of the same views painted twenty years earlier” (Emmanuelle Amiot-Saulnier, in catalog). And there is always to keep in mind that while it is true that Claude Monet is always changing languages, for the sake of completeness, around the same years, between 1910 and 1912, Kandinsky’s first abstract watercolor was made. Another great revolution in art. After Monet.

On the rest, to get an idea of the great decorations also present at the Marmottan but whose highest expression is the Musée de l’Orangerie, there are other monumental Water Lilies that evoke the last forty-three years of his life and career, in Giverny.

Since settling with his wife Alice in this region of the Marne, Monet, buoyed by his successes, including financial ones, made his Water Garden, greenhouses and studio, and invented some floral motifs that he would use or stylize in his paintings. Here, he also has a small pond dug and a small bridge built in the Japanese style. He buys more land, and even has permission to divert the course of a river, so he enlarges the pond and inserts many varieties of flowers, choosing all those that promote the beauty of the views - willows, alders, rhododendrons, rushes and bamboo. There is no shortage of white nenufaro (i.e., white water lily) and yellow nenufaro, and several hybrids, he has the deck covered with wisteria bows-a reminder of the Japanese prints he collects. He will live here to the end amid the whispers of his nenufar...

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.