by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 12/12/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Tied by a Girdle' in Prato, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio, from September 8, 2017 to February 25, 2018.

If we wanted to picture Prato at the dawn of the thirteenth century, we would have to recall the image of an industrious city, at the height of its economic and demographic growth, organized as a free commune from the beginning of the twelfth century, yet eager to find its own identity, capable of distinguishing it from nearby Pistoia, on whose diocese it depended, and from the cumbersome and powerful Florence: these were the two poles (one religious, the other political) within which Prato was squeezed. And if such an operation succeeded, perhaps the people of Prato have to thank the precious relic kept in their cathedral, that sacred girdle that represents not only an object to be venerated by the faithful during the ostensions: that strip of fine brocade, documented from the middle of the thirteenth century, has in fact constituted for centuries a strong identifying trait of the city, a reason for social cohesion, a source of undisputed prestige, even a resource capable of conveying the name of Prato around the world. It goes without saying, therefore, that numerous images have been dedicated to the sacred girdle and its myth: many of them are on display until the end of February at the exhibition Prato dedicates to its relic.

Tied by a Girdle (this is the title of the exhibition, currently underway at the Museum of Palazzo Pretorio) is therefore a review centered on an iconographic tradition, and the great merit of the two curators, Andrea De Marchi and Cristina Gnoni Mavarelli, is that of having been able to set up a structure capable of developing a broad discourse, endowed with a very high philological rigor and supported by a first-rate scientific project, which finds its acme in theunprecedented recomposition of the altarpiece painted by Bernardo Daddi (Florence, c. 1290 - 1348) for Prato Cathedral (probably for the chapel of the Assumption), but which also offers several other reasons that make it extremely convincing. We list just a few of them: the desire to investigate the origins of the iconographic theme of the sacred girdle, the analysis of the affinities and differences between Prato and Sienese iconography, and the in-depth study of the ostensions and the spectacularization of the cult of the sacred girdle. The exhibition examines a historical period from the twelfth to the eighteenth century, although the largest portion is reserved for works and artifacts executed before the sixteenth century: a choice that is consistent with the historical evolution of the cult of the sacred girdle, and, if we want, even obligatory, since the fortunes of this iconographic theme experienced a slow decline starting in 1512, the year of the sack of Prato, one of the most horrendous events in Italian history, against which the appeals of the people of Prato to their relic were of no avail (chronicler Luca Landucci recounts that the Spaniards, called by Pope Julius II determined to restore Medici power in Florence, “killed everyone who came before them, and it was not enough for them to have such a great booty, that they did not pardon the life of a person”). But this decline, Rita Iacopino specifies in her catalog essay, was also due to “the consequences of the Protestant world’s invectives against the distortions of the cult of relics, which were followed after the Council of Trent by the Catholic Church’s reflections on superstitions connected with certain devotional practices.”

|

| The entrance to Palazzo Pretorio in Prato for the exhibition Legati da una cintola (Bound by a Girdle) |

|

| A room of the exhibition Bound by a Girdle |

|

| A room of the exhibition Bound by a Girdle |

The exhibition takes its starting point from what represents the earliest known depiction of the sacred girdle theme in the history of Western art. It is a relief executed by one of the greatest sculptors of his time, the Master of Cabestany (active between Catalonia and Tuscany in the second half of the 12th century): A probable fragment of the ancient Romanesque portal of the church of Notre-Dame-des-Anges in Cabestany, a French town on the border with Spain, the sculpture (one of the masterpieces of the anonymous Master) presents, in the highly expressive style typical of the artist, three episodes of the Virgin’s Transit, namely Mary’s exit from the tomb (on the left, with Christ welcoming her into his arms and the apostles witnessing the scene), theAssumption (on the right: we see Our Lady, with her eyes closed, being carried to heaven by angels), and the glorification (the central scene). In the space between the exit from the tomb and the glorification, note the figure of St. Thomas holding a jeweled girdle in his hands: according to legend, the unbelieving saint had received the artifact from the Virgin at the time of the Assumption as proof of her actual ascent to heaven. The presence of such a figuration is due to the fact that the Master of Cabestany was also active in Prato (he is said to have worked on three capitals of the cloister of Santo Stefano), where already, in the mid-12th century, the cult of the girdle was rooted.

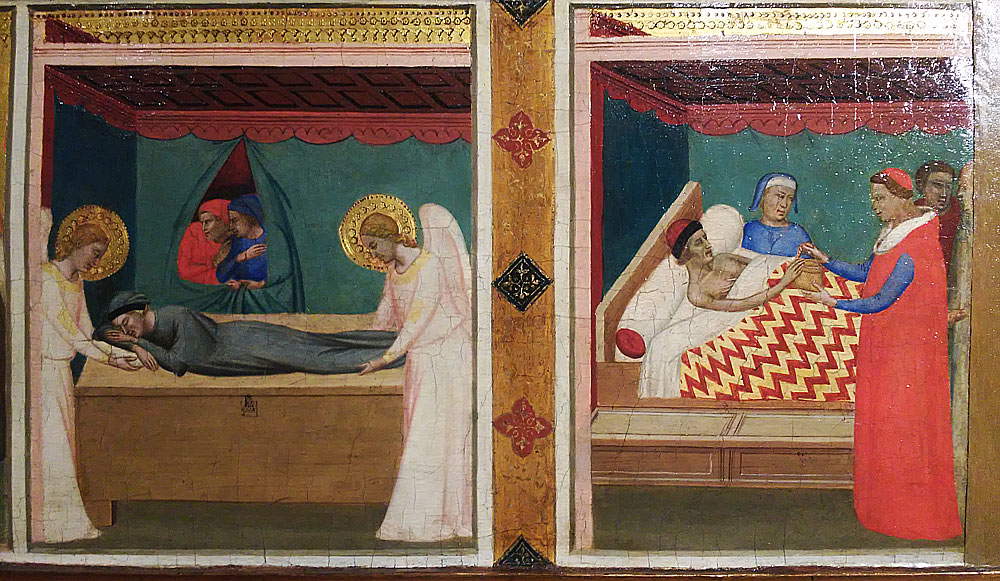

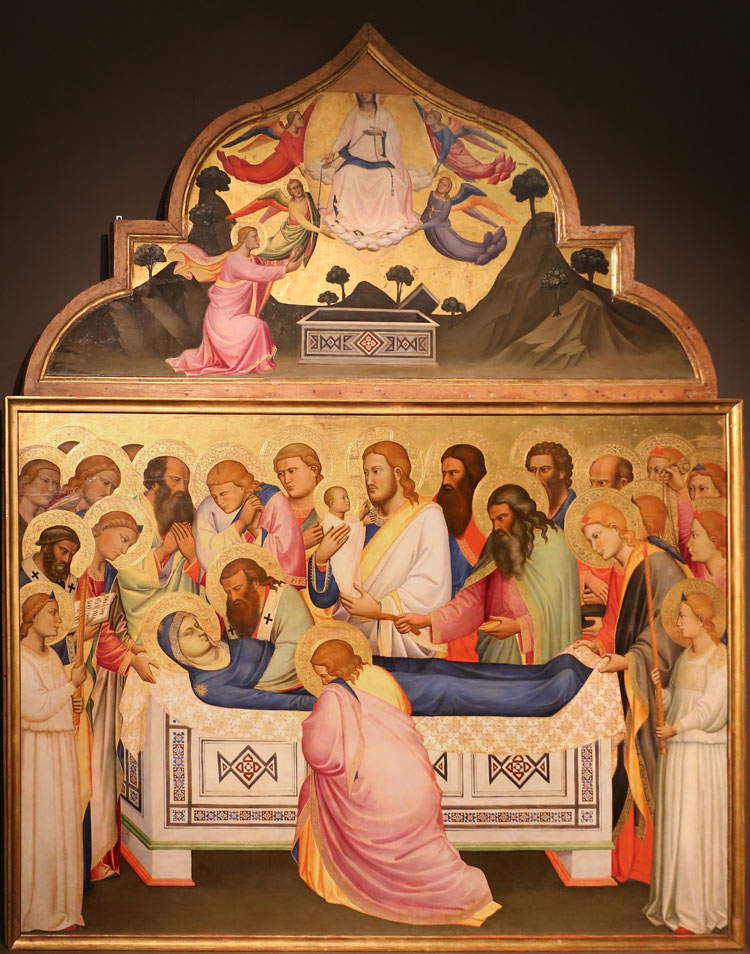

The origins of this belief are excellently reconstructed by Renzo Fantappiè in his contribution to the catalog. Legend has it that the girdle was brought to Prato in 1141 by a Michele da Prato variously identified by the different variants of the story (the best known of which has him belonging to the noble family of the Dagomari), who is said to have received it as a dowry from a young woman from Jerusalem whom he met during a trip to the Holy Land and with whom he would later marry: the girl, named Maria, according to the myth was the daughter of a priest whose family had been guarding the relic for centuries, given to an ancestor directly by St. Thomas. Still tradition has it that in 1172 the merchant, having come to the end of his days, wished to leave the girdle to the proposed St. Stephen’s parish church (later to become the city’s cathedral): thus the work would still be preserved in Prato’s main house of worship today. What has just been narrated is a sort of fable that has always circulated to justify the presence of the girdle in Prato: it is, however, almost certain that the relic arrived on the banks of the Bisenzio in the 12th century, a time when frequent contacts between the Tuscan city and the Holy Land are attested, in the context of which passages of relics were not infrequently recorded. Passages that popular devotion then often cloaked in the legendary halo that would later feed the imagination of artists. And it is precisely in the Prato predella of Bernardo Daddi’s altarpiece, which we find in the next section of the exhibition, that the myth of the arrival of the sacred girdle in Prato is told. In brief, the seven remaining scenes recount the gathering of the apostles around the empty tomb of the Virgin who ascended to heaven, the handing over of the girdle, by St. Thomas, to a priest from Jerusalem (the ancestor of Michael da Prato’s father-in-law), the betrothal of Michael da Prato to Mary, the handing over of the girdle to Michael the journey of Michael and his wife to Prato, the angels moving Michael from the chest that held the girdle (myth has it that Michael slept on it every night, but was then lifted up by two angels so as not to allow a weight to weigh on the girdle), and the delivery of the girdle to the proposed Uberto.

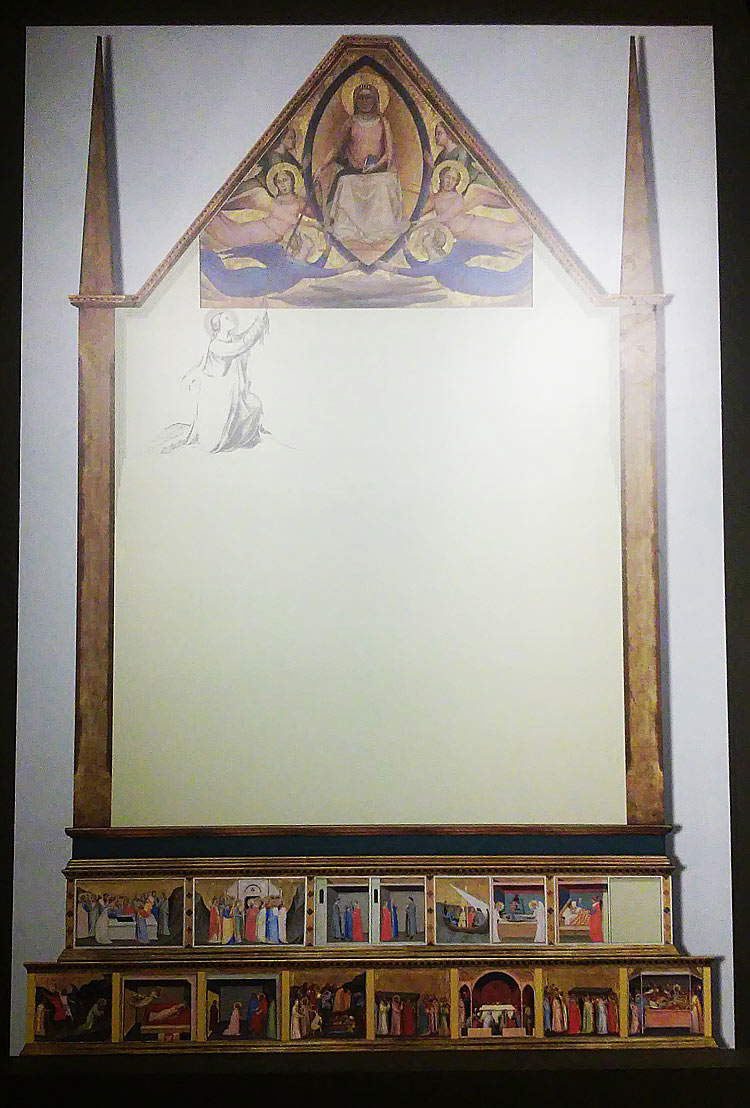

This would be one of the two predellas of the Assumption altarpiece: the other, preserved in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, presents eight stories of St. Stephen (and eight must also have been originally the scenes of the predella now preserved in the Museo di Palazzo Pretorio in Prato: the last panel, in all likelihood, must have depicted the entrance of the girdle into the parish church of St. Stephen). Painted between 1337 and 1338, Bernardo Daddi’s great altarpiece has unfortunately come to us dismembered, and the exhibition Legati da una cintola (Bound by a Girdle ) was an opportunity to bring together the surviving parts and propose areconstruction hypothesis: in fact, it should be pointed out that there are no documents attesting to certain links between the two predellas, so much so that some scholars had rejected the hypothesis that both belonged to the same work, partly because of the dissimilarities presented by some of the punching. Andrea De Marchi, on the other hand, revived the hypothesis of the common belonging to the Prato altarpiece: Bernardo Daddi had already conceived of a similar work (the polyptych of Santa Reparata), but there are also other details that support the curator’s idea, some of a technical nature (the recurrence of certain elements in the punzonature of all three fragments), others of an iconological nature (the presence of the figure of St. Lawrence in the Vatican predella is due to the fact that the cult of the saint was in force in Prato, and the fact that the scenes focus not on the life of the saint, but rather on the translations undergone by his body after his martyrdom, which then arrived in Rome from Jerusalem, would for De Marchi constitute a parallel with the journey of the girdle, which likewise came to Italy from the Holy Land), and still others of a historical nature (in the 15th-century frescoes in the Assumption Chapel of Prato Cathedral appears a rare figuration of the Reunion of the Bodies of St. Stephen and St. Lawrence, already present in the Vatican predella: probable “homage” to the Daddesque altarpiece).

The setting, which places the two predellas in sequence, on a wall next to the one where theAssumption is instead displayed, allows us to fully appreciate their refinement and narrative abilities (to the latter, moreover, is dedicated the section of the exhibition that displays four scenes, two stories of St. Cecilia and two of St. Reparata, belonging to two other predellas: those of St. Reparata were part of the aforementioned polyptych, made for the cathedral of Florence). It is difficult to give an account of a single exemplifying episode, but it is also impossible to avoid emphasizing the gestural expressiveness of the scene with the handing over of the sacred girdle to Michael of Prato (with his mother-in-law inviting her son-in-law to take care of the basket containing the relic, and the young man from Prato who, bringing his index finger to touch his chest, almost shows uncertainty in accepting such a demanding task), the delicacy with which the angels lift his body from the chest, the expressiveness of the apostles in the first scene of the predella from Prato. Note then how the belt present in all the scenes of the predella and in the cusp with the Assumption (the Virgin hands it directly to St. Thomas: we see a portion of the hands on the lower edge, while the rest of the figure must have been in the missing central panel) is indeed the Prato one, in fine green wool brocaded in gold threads and ending at the ends with peneri, that is, with decorations similar to long tassels.

|

| Master of Cabestany, Death, Glorification and Assumption of the Virgin with St. Thomas showing the girdle (c. 1160; white marble, 205 x 84 x 22 cm; Cabestany, Church of Notre-Dame-des-Anges) |

|

| Master of Cabestany, Death, Glorification and Assumption of the Virgin with St. Thomas showing the girdle, detail |

|

| Bernardo Daddi, THE Assumption of the Virgin (1337-38; tempera and gold on panel, 113 x 142.6 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection) |

|

| Arrangement of Bernardo Daddi’s predellas |

|

| Bernardo Daddi, Stories of the Holy Girdle (1337-1338; tempera and gold on panel, total 27 x 213 cm; Prato, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio) |

|

| Bernardo Daddi, Apostles around the empty tomb of the Virgin and St. Thomas showing the girdle, from the predella with seven scenes from the Story of the Girdle (1337-1338; tempera and gold on panel, total 27 x 213 cm; Prato, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio) |

|

| Bernardo Daddi, Michael’s Engagement to Mary and The Mother of the Bride Handing Michael the Basket with the Girdle as a Dowry, from the predella with seven scenes from the History of the Girdle (1337-1338; tempera and gold on panel, total 27 x 213 cm; Prato, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio) |

|

| Bernardo Daddi, Michael Moved by Angels and Delivery of the Girdle to the Proposed Uberto, from the predella with seven scenes from the History of the G irdle (1337-1338; tempera and gold on panel, total 27 x 213 cm; Prato, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio) |

|

| Reconstruction of Bernardo Daddi’s altarpiece |

The next section is intended to give an account of the spread of the cult of the sacred girdle from the 14th century onward, a century in which the iconography experienced considerable fortune, spreading throughout Tuscany: nevertheless, one of the most interesting works in the exhibition itinerary is still from Prato, namely the set of marble reliefs that Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia (documented between Siena and Prato from 1356 to 1360) made for the pulpit of the Cathedral of Santo Stefano, from which the priest showed the girdle to the faithful during the rite of ostension, which, Claudio Cerretelli informs us in the catalog, is documented from 1276 (while the oldest documentary mention of the relic is from 1255). It consists of four scenes depicting the Stories of the Virgin and the Girdle: the Dormitio, theCoronation of the Virgin (the latter, however, not present in the exhibition), Our Lady giving the girdle to St. Thomas, and St. Thomas handing the girdle to the priest of Jerusalem: interesting to note, as Camila Stefania Amoros points out in the catalog entry, the points of tangency between Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia’s work and Bernardo Daddi’s altarpiece, particularly in the figure of the Virgin seated within a mandorla giving the girdle to a kneeling St. Thomas with joined hands. The iconographic type present in Daddi and in Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia knew a rapid diffusion in the Florentine and Prato areas (the Sienese iconography, however, is different, as will be seen in a moment): we find him in several works exhibited at Palazzo Pretorio, starting with an altarpiece by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini (Florence, documented from 1368 to 1414) with Dormitio Virginis and Assumption, filled with references to other coeval paintings (the Dormitio scene traces in an almost literal way the homologous dossal that Giotto executed for Orsanmichele in Florence, which is now preserved in Berlin, and the same goes for theAssumption, borrowed from a relief executed by Andrea Orcagna, also for Orsanmichele), and from a triptych also by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini (but later and more refined) in which the saint, unlike in the earlier work, already touches the girdle that the Virgin is passing to him.

Indeed, looking at the paintings one will notice slight variations in the depiction of the passing of the girdle. Of particular interest is a panel painting by Lorenzo di Bicci (Florence, documented from 1370-before 1427), from the church of Santo Stefano in Empoli and now housed in the Tuscan city’s Museo della Collegiata, which works a kind of mixture between Prato iconography (with the saint at the side of the Madonna receiving the girdle by touching or brushing against it) and Sienese iconography (St. Thomas and the Madonna are on axis and the girdle hovers in the air descending toward the unbelieving apostle): here we see that the saint approaches the Madonna until he reaches below her knees, and the Virgin, before giving him the girdle, seems almost to show it to him, with the apostle welcoming it with arms wide open. This was a solution that Lorenzo di Bicci adopted, as Giovanni Giura explains in the catalog entry, because it was “perhaps more congenial to his geometric painting and his cooled expressiveness, which focuses rather on the precision and elegance of the drawing and decorative elements.” He would be echoed a few years later by his son Bicci di Lorenzo (Florence, 1373 - 1452) in the colorful Lastra a Signa triptych, where the vertical axis between the Madonna and St. Thomas is almost perfect.

|

| Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia, The Assumed Madonna Giving the Girdle to St. Thomas (left: 1359-1360; marble, 100 x 198 cm; Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) and Dormitio Virginis (right: 1359-1360; marble, 92.5 x 197.5 cm; Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

|

| Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia, The Assumed Madonna Giving the Girdle to St. Thomas (1359-1360; marble, 100 x 198 cm; Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

|

| Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, Dormitio Virginis and Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1370-1375; tempera and gold on panel, 243 x 202 cm; Parma, National Gallery). Ph. Credit |

|

| Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, The Assumpted Madonna Giving the Girdle to St. Thomas and Six Angels, Between St. George, St. John Gualbert, St. Lawrence and St. Francis (c. 1413-1415; tempera and gold on panel, 181 x 199 cm; Arezzo, Basilica of San Francesco) |

|

| Lorenzo di Bicci, The Assumed Madonna Giving the Girdle to St. Thomas, and Four Angels (c. 1395-1400; tempera and gold on panel, 146.5 x 81.4 cm; Empoli, Museo della Collegiata) |

|

| Bicci di Lorenzo, The Assumed Madonna Giving the Girdle to St. Thomas with Angels and Seraphim between St. Nicholas of Bari, St. Andrew, St. John the Baptist, and St. Anthony Abbot (c. 1420; tempera and gold on panel, 158 x 178 cm; Lastra a Signa, Museo di Arte Sacra di San Martino a Gangalandi) |

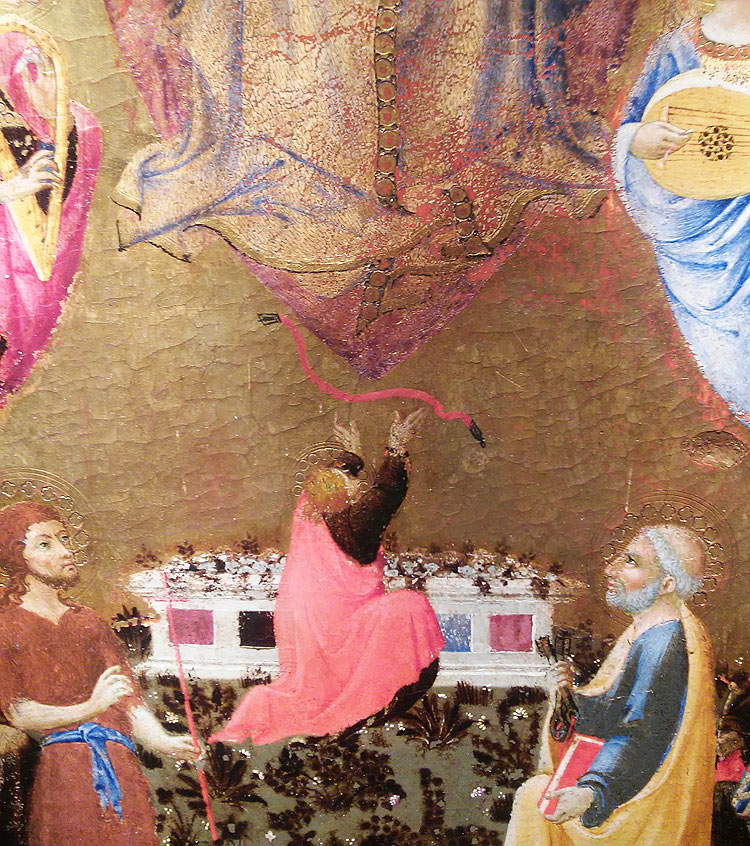

The only encounter with Sienese iconography offered by the exhibition (excluding Vecchietta’s sculptural group depicting the Assumption, which has not been preserved in its entirety) takes place in front of a panel by Sano di Pietro (Siena, 1406 - 1481), which we find on the upper floor, in the penultimate room: the exhibition, it should be emphasized, proceeds according to a strict chronological scansion from which it rarely deviates. In Sano di Pietro’s panel, the girdle is almost caught on the fly by a Saint Thomas in the center of the scene, ready with his hands to welcome the Virgin’s gift. The work, dating from around 1445, follows shortly after the beginning of the spread of the iconography of the sacred girdle in Siena: a spread due to the fact that Siena, too, boasts the possession of a fragment of Mary’s girdle, acquired in 1359 from the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala. The fifteenth-century altarpieces exhibited in the same section, and roughly contemporary with the panel by Sano di Pietro, show that they accept the iconographic type of the Madonna by Lorenzo di Bicci: this is true of Filippo Lippi (Florence, 1406 - Spoleto, 1469), who is present with a work preserved in Palazzo Pretorio itself and, because of certain stylistic differences, probably finished by the workshop. This is the panel painting intended for the church of the monastery of Santa Margherita: here, too, we note how the Madonna shows the girdle to St. Thomas before giving it to him. This is also an important painting for the anecdote about Filippo Lippi since, according to Vasari’s writing, the friar painter fell in love with the young Lucrezia Buti, a nun in Santa Margherita, just as he was working on the altarpiece: in the work, Saint Margaret (the first on the left) would show precisely the features of the girl with whom, as is known, the painter later fled (precisely on the occasion of a display of the girdle). Similar approach is the one that Neri di Bicci (Florence, 1418/1420 - 1492), son of and grandson of Bicci di Lorenzo (interestingly, the whole family is represented in the exhibition), gives to the altarpiece now in the Museo Diocesano d’Arte Sacra in San Miniato.

Along these lines the sixteenth-century representations would later be maintained throughout the century. Simple, but intense in its almost intimate dialogue between the Madonna and St. Thomas, is the panel by Ludovico Buti (Florence, c. 1550/1560 - 1611), to whose hand it was first ascribed in 2002: a work in which the gazes and gestures “accompany the viewer in an atmosphere of serene religiosity” (Rita Iacopino) and which is influenced by the devout and counter-reformed painting of Florence in the second half of the 16th century. The references, in particular, hark back to the atmospheres of Santi di Tito (Sansepolcro, 1536 - Florence, 1603), present in Palazzo Pretorio with a Madonna Assunta donating the girdle to St. Thomas, where even the saints who assist are participants in the exciting moment that St. Thomas is experiencing (the visual directions lead the viewer right to the girdle: the religious climate of the time demanded works that were easy to read and capable of leading the viewer to feelings of sincere piety and devotion).

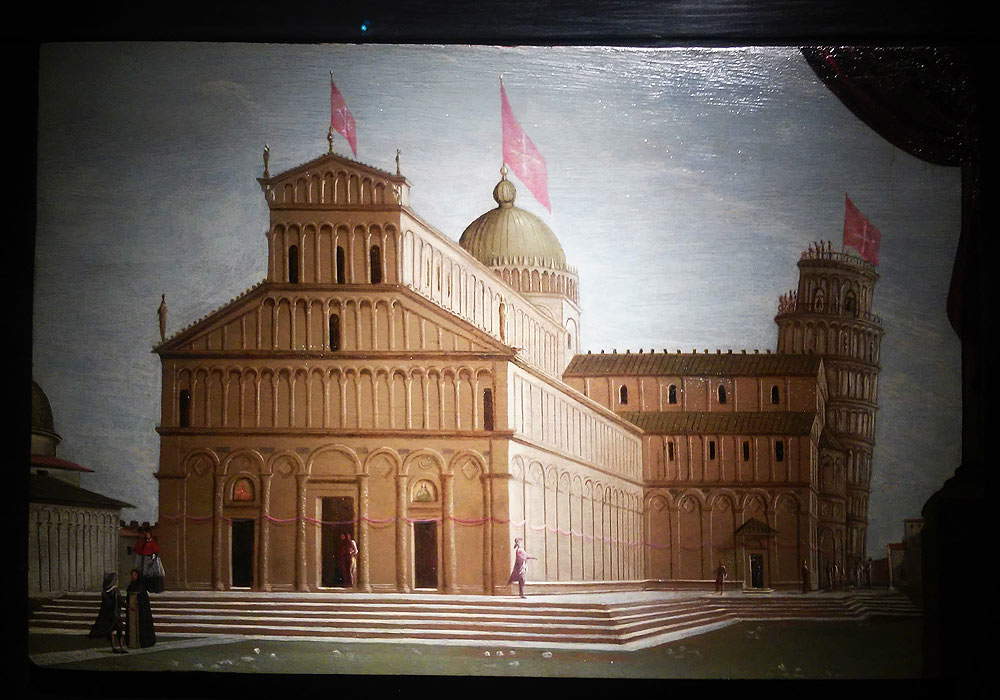

The Prato exhibition concludes with works that offer living testimony to the worship and ostentations of the sacred girdle. Of particular historical interest is a tablet assigned to Pietro Ciafferi (Pisa, 1604 - 1661) that presents a View of Pisa Cathedral during the display of the Girdle: an unpublished work, it represents one of the earliest known views of the monumental complex of the Pisan cathedral, here depicted in a festive moment, as the Pisan flags hoisted on the facade, dome and tower, as well as the “Cintola” itself fixed all around the monument as a sign of devotion to the Virgin Mary, suggest (the custom of the “Cintola” was typical of the Feast of the Assumption, which is celebrated on August 15, but could also occur on other occasions). There is also no shortage of paintings depicting the display of the relic: Of particular interest is the painting by Giovanni Pietro Naldini (Settignano, 1580 - Prato, 1642) that one encounters toward the end of the itinerary and that “captures” the moment when the girdle is presented to the faithful by Cardinal Carlo di Ferdinando de’ Medici, who stands just below Giovanni Pisano ’s Madonna and Child still preserved in the Chapel of the Girdle (of which the painting provides an accurate description) and dressed, according to the custom in vogue until the twentieth century, in an embroidered cape and tiara. It is impossible to leave the exhibition without seeing the three containers that have held the relic over the centuries: the highly refined capsella of 1447-1448 by Maso di Bartolomeo (Capannole in Val d’Ambra, 1406 - Dubrovnik, 1456); the seventeenth-century case by Matteo Fattorini (Florence, 1600 - 1678); and the famous Teca della Sacra Cintola, made in 1638 by an unspecified Milanese goldsmith and important as the first transparent container, able therefore to show the girdle to the faithful without the need to force the priest to extract and handle it.

|

| Sano di Pietro, The Assumed Madonna among Musician Angels Giving the Girdle to Saint Thomas among Saints (c. 1445; tempera and gold on panel, 69.3 x 53.5 cm; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Sano di Pietro, The Assumpted Madonna among Musician Angels Giving the Girdle to Saint Thomas among Saints, detail |

|

| Neri di Bicci, The Assumed Madonna Giving the Girdle to Saint Thomas between Saint John the Baptist and Saint Bartholomew (c. 1480; tempera and gold on panel, 176 x 170 cm; San Miniato, Museo Diocesano d’Arte Sacra) |

|

| Filippo Lippi and workshop, Our Lady of the Assumption Giving the Girdle to St. Thomas between St. Gregory, St. Margaret, St. Augustine, Archangel Raphael, and Tobiolo (c. 1456-66; tempera and gold on panel, 199.5 x 191 cm; Prato, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio) |

|

| Ludovico Buti, Madonna Giving the Girdle to St. Thomas (1588-90; Prato, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio) |

|

| Pietro Ciafferi, View of Pisa Cathedral at the setting of the Girdle (c. 1640-1650; oil on panel, 32.5 x 39 cm; Milan and Pesaro, Altomani & Sons) |

|

| Giovanni Pietro Naldini, Ostensione della sacra cintola (c. 1633; oil on canvas, 97.5 x 136.5 cm; Prato, Private Collection) |

|

| Maso di Bartolomeo, Chapel of the Sacred Girdle (1447-1448; gilded copper worked by casting, embossing, burin, horn and ivory on wooden core, spun gold brocaded silk satin, 21.1 x 13.2 x 14.1 cm; Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

All in all, there are several strengths of Legati da una cintola, an excellent exhibition that right from its title reveals the intention to recognize, in the protagonist relic, an element of unity for the citizens of Prato. It is a research exhibition that leaves the field open for new contributions (one example: it is still unclear exactly where Bernardo Daddi’s altarpiece was destined for), that offers a broad overview of a Prato iconography that later spread throughout the region, that intends to go beyond the confines of Palazzo Pretorio (in fact, it should be pointed out that for the duration of the exhibition the public can visit the Chapel of the Sacred Girdle in Prato Cathedral, which is usually closed, and admire the frescoes by Agnolo Gaddi and the aforementioned Madonna by Giovanni Pisano up close), and which also gives great importance to the so-called minor arts, since works of goldsmithing, liturgical vestments, belts and illuminated manuscripts (some of which date back to the 13th century) are enhanced by a layout and a didactic apparatus (concise and above all effective in emphasizing the most important aspects) that guarantee them no less weight than that reserved for paintings or sculptures. Exemplary, finally, is the catalog published by Mandragora, a publication of great quality and undoubted scientific density that crowns a review to visit and capable of leaving both scholars and the public satisfied.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.