A dreamlike dimension teeming with devils, monsters, visions and apocalyptic fires is what distinguishes the disturbing art of Dutchman Hieronymus Bosch. A vision, his, that helped shape a different Renaissance, one that opposed a passion for classical antiquity with an interest in the dark and bizarre. And that is precisely what the new exhibition open to the public until March 12, 2023, at the Royal Palace in Milan, Bosch and Another Renaissance, tries to tell the story of, even if visitors, driven by their fervent passion for the Dutch painter, might see their expectations dashed in finding only a handful of works belonging to the artist. However, the Milan retrospective, curated by Bernard Aikema, Fernando Checa Cremades and Claudio Salsi, takes it upon itself to narrate not only Bosch’s work, but also and above all a foreign Renaissance, trampled and engulfed by the grace and balance of the typical Italian one. And once compromised and free of preconceptions, one might be surprised to learn about a new, if you will, dystopian world, and certainly different from what one is used to.

The visitor begins a journey in the dimness of the rooms by following spirits, monstrous creatures and trivial desires, nurturing that same shadow that Jung defined as the archetype of the devil and of all those possibilities of existence rejected because they are not considered their own. Thus, one enters the room that houses, first, the labyrinthine world of the Temptations of St. Anthony, Bosch’s triptych dating from 1502.

The large work, visible on the front and back, puts such an abundance of droleries on display for the first time that the main subject almost disappears. Anthony was regarded as the archetypal hermit and “father of monks,” and Bosch most likely got to know his story through consultation of the Vitas Patrum and through the widespread flourishing, from the second half of the 15th century, of monasteries and convents in the Netherlands. The panels of the triptych depict, from left to right, the three basic stages of the saint’s life, from the time when Anthony embraced the hermit life, through the persecution of the devil, to the overcoming of temptation and the subsequent attainment of inner peace. On the first sash St. Anthony is depicted twice: while being supported, unconscious, by two monks after an attack by the devil and, later, in ecstatic prayer being carried through the air by demons. The latter scene was extremely congenial to the artists of the time and describes an event that occurred relatively late in the saint’s life. One morning, in fact, while meditating he fell into ecstasy and had an apparition: he saw himself being carried through the air, now by two angels, now by two devils who demanded a reckoning for the sins of his youth. From here the elements of Bosch’s world descend into chaos, in a hodgepodge of strange figures, such as a devil-wolf, a devil-rider holding a fish for a spear, flying fish, and, in the meadow, a giant (also a recurring motif in the saint’s story) whom Bosch depicts on all fours as he takes on the appearance of a tavern. The Dutchman’s tavern represents all the ambiguity of the world, sin and the diabolical trap for souls, while recurring motifs and symbols alluding to the journey are found in the landscape.

The central panel depicts the crucial phase of the struggle against the demons massed in large groups around the saint, who will attack in the last panel. Here Anthony is instead depicted kneeling intent on observing the viewer, while the diagonal of his back accompanies his gaze to the blessing Christ before his crucifix. The last panel depicts St. Anthony’s meditation, while figures fly through the sky to the witches’ sabbath. In the very foreground is a naked woman, Lust, as she emerges from a log offering herself to the meditating saint. Near Antony a dwarf with pinwheel and red cloak, symbol of unconsciousness, and, again, in the foreground the last temptation: a table with bread and wine. It was the Venetian chronicler Marcantonio Michiel who first described Bosch’s art as peopled with “hells, monsters and dreams,” outlining the profile of an extremely imaginative artist and “pictor gryllorum,” that is, a painter of ridiculous scenes.

Far more sweetened and dreamy is the staging of the meditations of St. John the Baptist, which for conservation reasons will leave the exhibition on Feb. 13. The saint is depicted here meditating on a meadow and immersed in a landscape that is more realistic than the other works on display. But the illusion is shattered immediately with the Triptych of Hermit Saints. Bosch executed this oil on panel between 1495 and 1505: in the central panel St. Jerome, recognizable by his cardinal’s robes, cross and lion, wanders in the desert interrupted by ruins and bas-reliefs. The landscape continues in the left panel featuring St. Anthony Abbot, while, in the right panel, St. Aegidius is depicted together with the doe that fed him during his journey as a hermit.

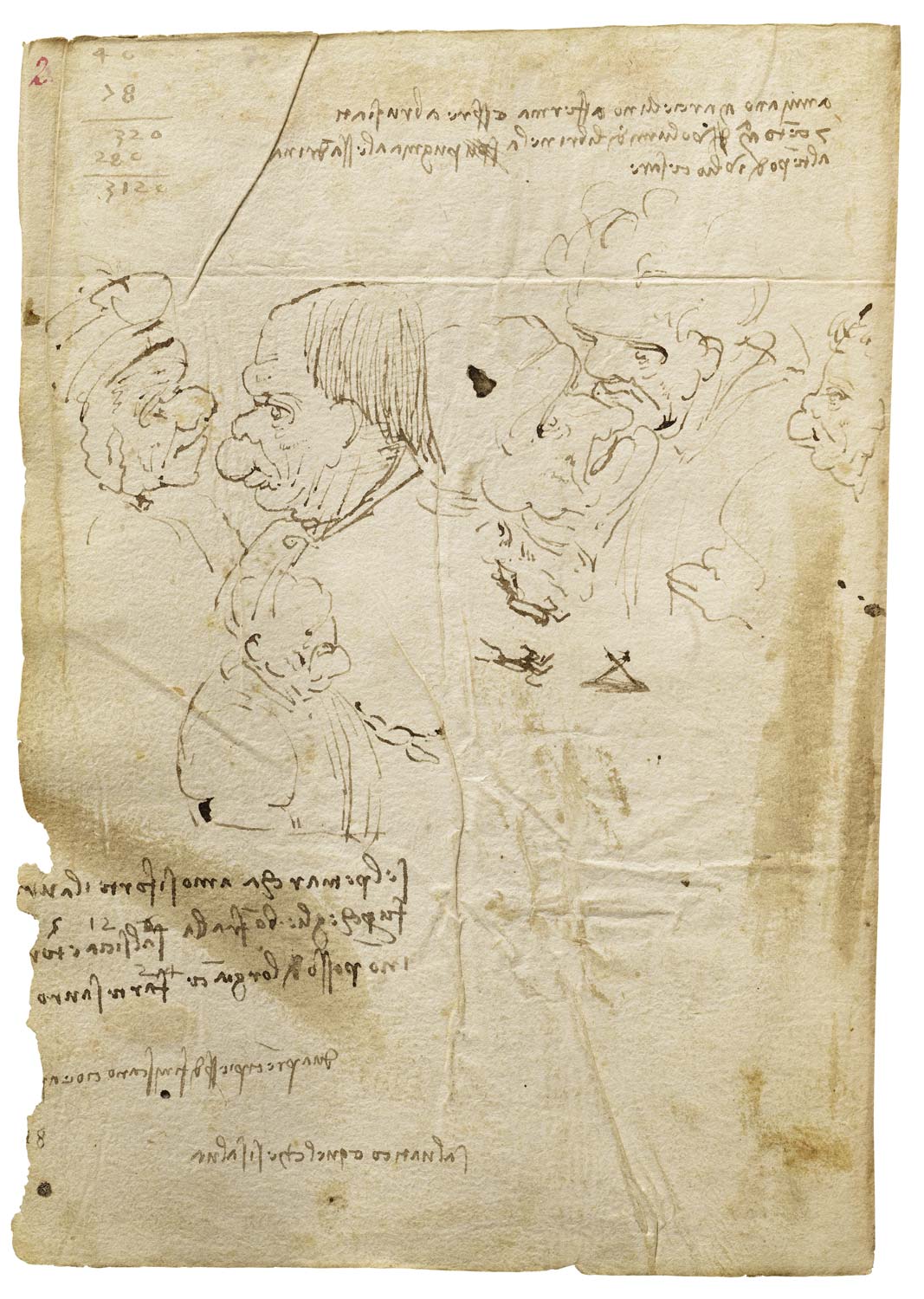

From here develops the entire path of the exhibition, which follows not a precise chronology, but different themes that accompany the public on a journey almost among the saint’s own temptations, making them find themselves now in a struggle between classical and anti-classical, now among dreams, magic, and apocalyptic visions, now among prints, curiosities and macabre collecting. The second room, in which the theme of “classic and anticlassical between Italy and the Iberian Peninsula” is addressed, tells the other side of the Renaissance by opening with a post-Bosque version of the Temptations of St. Anthony by Jan Wellens de Cock, from 1525. This space also houses one of the greats of the Italian Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci, with some grotesque caricatures from one of the pages of the Codex Trivulzianus. And here is opened a small Pandora’s box that puts in the balance the certainties regarding an era that, under the layer of hymns to beauty and measure, actually hid the same freakish monstrosity typical of Bosch’s art, demonstrating how a Renaissance made of hybridizations and fascinations for the eccentric was not the exclusive prerogative of Nordic art. It continues, then, among the hallucinated and nightmare-filled “dreams” of Marcantonio Raimondi, Albrecht Dürer, and the artists of Bosch’s workshop, passing through the pages of a manual for the divination of the future through the reading of the symbols present in dreams.

Dreams, in the sixteenth century, seduce and unsettle, and endless would be the treatises or pictorial representations such as, for example, The Vision of Tundalo (c. 1491-1525), which stages the initiatory journey of the knight who visited the afterlife for three days. The legend is painted here by a follower of Bosch, who depicts the sleeping knight sitting low while being assisted by an angel. But the knight seems almost a secondary element in comparison with the large head with empty eyes and from whose ears trees grow, while coins flow from his nose. To the right are countless elements characteristic of the Woodland repertoire, such as a burning castle, shady figures and strange little monsters. Concluding the fierce nightmare is a woman asleep on a bed surrounded by beasts, as if she were the meal of a macabre banquet.

Almost as if searching for an intrinsic meaning and some reason for these morbid dream visions, the traveler will be guided to the hall of magic, where the woman is displayed as an object and, often, considered the devil. Thus, one discovers a famous engraving, the Stregozzo, derived from a burin by Albrecht Dürer, and which in turn echoed a graphic invention by Mantegna, where the witch is depicted as a laid old woman with loose hair as she rides the skeleton of a terrifying animal and feeds on children snatched from their families on the night of the Sabbath of Hell.

Continuing along the path, one can see even better how the curators, by including connections with Italian artists of the same period, have followed through on their difficult task of reconstructing a Renaissance made up of light and shadow, life and death. A Renaissance with one great beating heart, in which monstrous and grace contaminate, mingle and learn from each other.

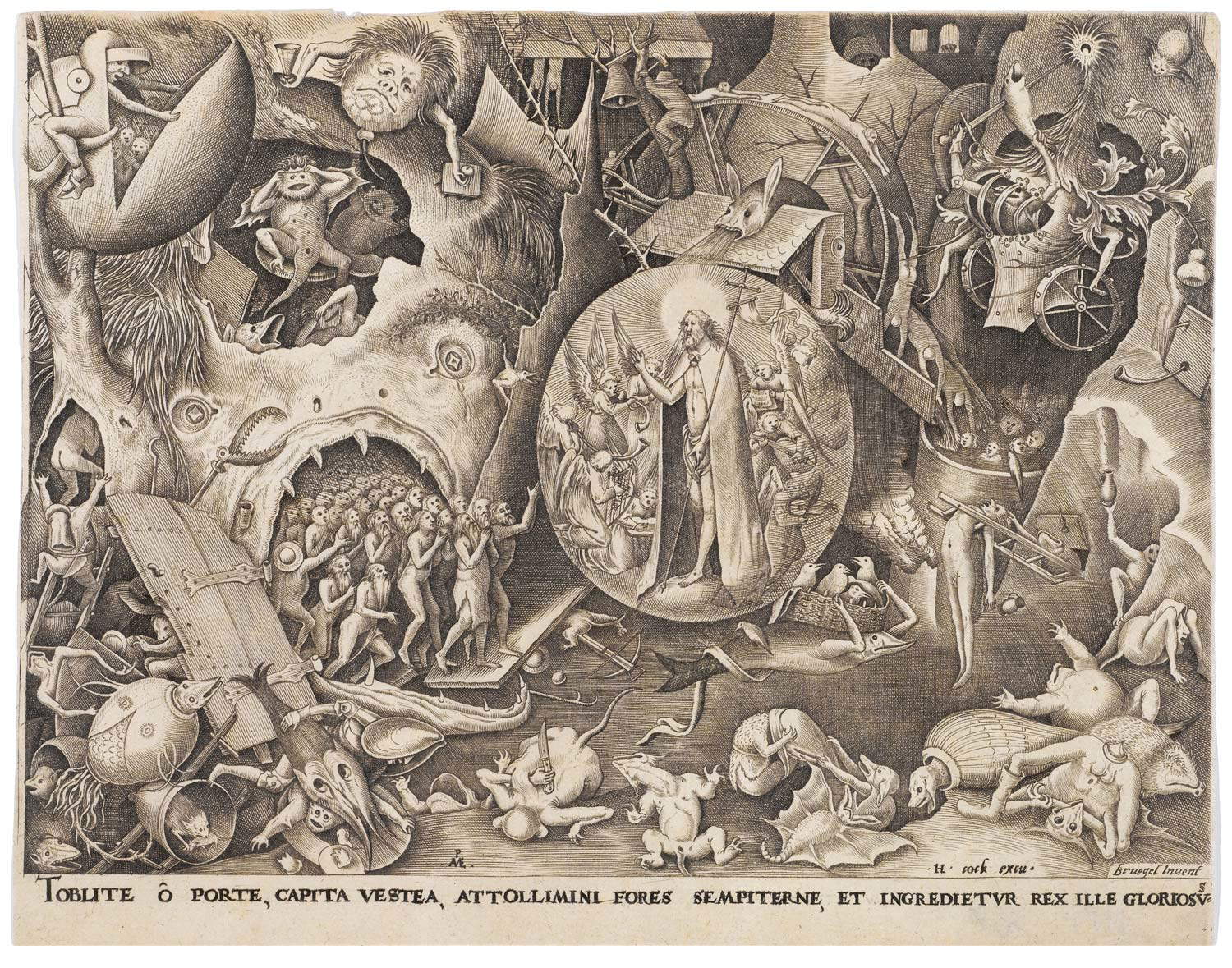

Thus, in the room of Apocalyptic Visions, another colossal dialogue is presented, this time between Dante Alighieri, with his Comedia, and the peculiar representations of Herri met de Bles II or the engravings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder that will return in the room dedicated to “the press as a medium of dissemination” among the strange figures of jesters and monsters precariously balanced between dreams and nightmares. Near them is another work by Bosch: the Triptych of the Last Judgment. An imposing oil on panel depicting, on the left, Heaven, on the right, Hell, and in the center, the Judgment carried out by Christ towering above a world of populated by creatures alluding to different sins.

Before delving into the world of prints, we return more thoroughly to the Temptations of St. Anthony, which was, without a doubt, one of the most successful themes of the poetics of Hieronymus Bosch and his followers. Belonging to the Dutch artist’s school is an unusually large canvas, dated 1554 and formerly erroneously attributed to Pieter Bruegel the Elder on the basis of the apocryphal signature “P.BRUEGHEL.” The subject of the Temptations of St. Anthony was often practiced by Bosch’s followers because it provided them with an opportunity to show off all those little monsters, demons and beings typical of the “Forest manner,” so much so that the saint’s sufferings were pushed into the background to make room for the fantastic pandemonium that fills the entire surface of the work, unlike in Bosch’s Temptations where the saint also retains an important role.

Hieronymus Bosch was not, however, loved and imitated only in his own lands: the Habsburgs, who ruled Brabant from the late 15th century, also had a deep attraction for him, so much so that Philip II kept a very large number of works by the artist and his circle in Madrid, at the Escorial and the Prado Palace. Granvelle’s collections also held a series of four tapestries “in the manner of Bosch” that entered the Spanish royal collection probably as early as the time of Philip II. So great was the success of the textile collection that Don Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, third Duke of Alba, came to own a similar series copied from Granvelle’s collection. In the area of the retrospective devoted to the Habsburgs, among the enormous tapestries, a small panel also representing the Temptations of St. Anthony stands out, but it was one of the first works by Bosch donated by Philip II to the Monastery of the Escorial, after he acquired it around 1563 from the Marquis of Cortes. Unlike the other depictions of the saint’s temptations, here Anthony is not assailed by the evil beings: the saint appears absorbed in his thoughts, sitting under the trunk of a hollow tree, and the devils, rather than tormenting him, appear to be comic figures, extraneous to the context. This very peculiar interpretation of the iconographic subject is one of the main reasons that led several authors to consider the painting as foreign to Bosch’s brushes, but technical studies on the subject have confirmed it to be autographed by the master. Following the labyrinth of tapestries belonging to the Habsburgs, the visitor is led to the small room of the elephant, a subject among the most fascinating in the emerging taste for exoticism in 16th-century Europe. Bosch himself depicted this animal in the Garden of Delights, and this section aims to highlight the fortune of this animal in 16th-century iconography.

The Milanese retrospective Bosch and Another Renaissance concludes its journey through curiosities and encyclopedic collecting by presenting a small “ideal reconstruction” of Wunderkammer that seems to seek a jarring parallelism with the marasmus of a shy workshop copy of the triptych in the Garden of Delights and “to make the relationship even more evocative,” as the curators write in the catalog, a “group of stuffed birds from the Milan Museum of Natural Sciences representative of the species recurring in Bosch’s painting is proposed.”

Thus, an unusual exhibition is being staged in the halls of Milan’s Palazzo Reale, despite the fact that it is not the first that Italy has dedicated to Bosch: in 2017, in the wake of the initiatives for the 500th anniversary of the painter’s death (2016), the Doge’s Palace in Venice had dedicated an in-depth look at the Dutch artist’s works in the Venetian public collections, all three of which had been restored for the occasion. But what is certain is that the opportunity to see even a small number of Bosch’s works gathered together in a single exhibition venue is rare, especially when included in an exhibition as extensive as Bosch and Another Renaissance, an exhibition that is also a sum of firsts: Milan, in fact, had never seen an exhibition on Bosch before, some previously unseen works are presented (such as the Descent of Christ to Limbo attributed to a Bosch follower and owned by the De Jonckheere Gallery in Geneva), and for the first time in Italy it is possible to see Bosch’s Triptych of the Temptations of St. Anthony .

The result in the end is a disturbing, dreamy journey pervaded by disturbing visions and different forms of anguish and hell. A hell that “the other Renaissance” pursued, hunted down and trapped forever in its art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.