There should be queues on Via delle Belle Arti, in front of the entrance to the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, which for two months has granted faculty to the city, to Italy, to everyone, d’admire displayed side by side the two versions of Guido Reni’sAtalanta e Ippomene, the one from the Prado in Madrid and the one from the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, brought together for three months in the context of an exhibition(La favola di Atalanta. Guido Reni and the Poets, curated by Giulia Iseppi, Raffaella Morselli and Maria Luisa Pacelli) aimed at exploring the intertwining of painting and poetry in early 17th-century Bologna, and what’s more, with important discoveries and rich new features. There should be queues, but many probably do not even know about this exceptional comparison, which has been missing in Italy for almost forty years and which would be announced around the world amid squawks, fanfare and storms of communiqués and advertisements: this was not the case, quite the contrary. In front of the two great paintings it also happens to be alone for many minutes. Was it a conscious choice to let everything pass in silence (although not at all agreeable, also because the exhibition, beyond its climax, is well constructed, appreciable, full of new ideas, and even suitable for a wide audience), or was it the consequence of a communication that was at least revisable? On how this exhibition was communicated it will be convenient to return at a later date: for now, we can focus on an exhibition that is part of a growing interest in Guido Reni, as evidenced by the many exhibitions that have been dedicated to him in very recent times, as well as by his increasingly insistent presence on the market (we can mention in this regard the Judith just purchased by the State for the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola in Genoa, or his works that animated the recent editions of the Florence International Antiques Biennial and Modenantiquaria).

The exhibition at the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna was created to introduce visitors to an idea obviously familiar to experts in seventeenth-century art, but perhaps unfamiliar to the general public: many of the paintings that we admire in museums, galleries, and the rooms of the great collectors of the past, or about which we have learned in art history books, are also to be read as products of a “cultural phenomenon,” as the curators define it, that did not fail to condition the choices of many artists, namely the perception that the visual arts and poetry were sisters. Indeed: “dear twins,” according to Giovan Battista Marino. It is the same idea that animates the concurrent exhibition on Poetry and Painting in the Seventeenth Century at the Galleria Borghese (which opened to the public a few days after the one at the Pinacoteca Nazionale): in Rome, the focus , however, is on Marino, considered as much in his guise as a poet as in that of a theorist, if you will, with whom one can say not only totally overcome the historical inferiority complex that ’art had always suffered vis-à-vis letters, but it could be considered to some extent reversed, since in the seventeenth century, on the contrary, it was often poetry that followed painting, trying to express in words what the immediacy of images suggested to the poet’s eyes. In Bologna, the exhibition finds itself exploring, probing, retracing the ramifications that this very fertile cultural humus followed in the city.

The audience is immediately provided with an appropriate, engaging context: we are in the second largest and most populous center of the Papal States, we are in the city of the Carracci, of Ulisse Aldrovandi, in the city where letters, arts and sciences flourished also as a result of the presence of the Studium, the city’s university, the oldest inEurope, as well as the numerous artists’ ateliers and, a new fact, the academies of painters and men of letters where new ideas were elaborated, where the marriage between poetry and painting was continually celebrated, a union that no one, by now, would dream of questioning, so much so that the first painting one encounters in the exhibition is a sort of manifesto.

If in the Galleria Borghese exhibition this sort of programmatic role was entrusted to Francesco Furini’s Pittura e Poesia (Painting and Poetry ), a work from 1626, in Bologna one can admire a painting animated by the same principle, Giovanni Andrea Sirani’sAllegory of the Three Arts (namely, painting, poetry and music), almost forty years more recent, but no less interesting, on the contrary: the four-decade gap between the first painted manifestations of the link between painting and poetry and the work on display at the Pinacoteca Nazionale is, if anything, testimony to how enduring the phenomenon investigated by the exhibition was (of course: if one wished, one could identify its offshoots up to the present day, but at the time the interweaving of art and poetry was not only at the center of cultural debate, but was a dominant model, and would remain so until well into the eighteenth century). At the center of the exhibition in Bologna, however, would seem to be a crucial element for understanding the relationship between art and painting in the seventeenth century, that is, the consideration that the painter’s craft enjoyed at the time: it is a declination of the theme that was touched upon by the exhibition at the Galleria Borghese and which, however, here in Bologna takes on, at least for the public, an even more defined, and certainly more immediate, physiognomy. One could, however, take the topic even more broadly: what did it mean to be a painter in early 17th-century Bologna? Who did the Carracci, Reni, Sirani, and their colleagues frequent at the time? What was the role of the artist in society? The idea that the artist was a kind of intellectual capable of collaborating with the literati to awaken minds from their torpor is beginning to be clearly perceived: the Accademia dei Gelati, on whose coat of arms stood a forest of trees dried up by the cold (the “gelati”), established in 1588 on the initiative of the physician Melchiorre Zoppio, had set itself the goal of fostering the thawing of minds frozen by ’ignorance, at first by the sole means of poetry, and then in an increasingly pervasive way, through the initiation of antiquarian research, the promotion of philosophical discussions, the patronage of broader initiatives (theatrical performances, for example), and the translation of ideas into works of art. Such cenacles could not do without the participation of artists, whose brush could give image form to ideas (“expressing perfect ideas,” academic Ercole Agostino Berrò would write in one of his speeches, moreover praising Guido Reni as the highest example of perfection): the painter is now not only perceived as a friend of the poets but, indeed, as a kind of autonomous intellectual, who can participate independently in the cultural debate by contributing his own ideas, his own knowledge. On the occasion of Agostino Carracci’s funeral in 1602 (on display are engravings reproducing the sets prepared for the occasion: Many of the leading Bolognese artists of the time participated, under the direction of a then 25-year-old Guido Reni), a publication was printed in which the Incamminati, or members of the academy founded by the Carracci, collected texts and poems produced in honor of therecently deceased artist, and in the introduction, written by the academician Benedetto Morello, one could read that the artists “not only show valer in drawing their principal study, but they discover themselves more than mezanamente indententi and of architectures, and of sculpture, and give essay of having cognitione of historie and fables; indeed with new thoughts, not only poetic, but philosophical, they give to see that they are not deprived of the cognition of sciences, and disciplines more noble and peregrine, the whole always accompanying with istupendo giudicio in applying it, and with rare shrewdness in arranging and ordering it, et insomma mostraresi such that they give hope of the happiest progress, if not manifest clarity of task value.”

This is how painters were perceived in early 17th-century Bologna. And in this dense web of correspondences between arts and letters, a position that was anything but marginal was that of the collectors, who were in contact with poets, frequented literary circles, often became members of the academies, and were regulars in the painters’ workshops, with whom they not infrequently became friends: Significant is the case of Cesare Rinaldi, who was a great friend of Agostino Carracci, to the point that he was portrayed by him in a splendid portrait in which the fine collector, also a poet, is depicted holding a pocket watch (“da saccoccia”, it would have been said at the time) and is immersed in a study in which appear all the objects of his singular Wunderkammer dedicated, too, to the union of poetry, painting and music (so here appear works of art, a lute, books, and more generally the instruments of the three arts). Another prominent collector was the younger Andrea Barbazzi, owner of a vast picture gallery that certainly included Ludovico Carracci’s Iole , another protagonist of the exhibition, on loan from the Manodori Foundation of Reggio Emilia. It is around Barbazzi that the most significant new features of the exhibition are concentrated: In fact, Giulia Iseppi, during her doctoral studies, discovered, in the library of the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Austin, Texas, a manuscript that allows us to shed new light on the figure of this poet, collector, friend of many painters (and especially of Guido Reni), and also to link to him one, or perhaps two, paintings that the exhibition presents to the public. The manuscript contains a collection of over three hundred of Barbazza’s poems, unpublished: they had been gathered by the author, as was the custom at the time, with a view to publication after his death. It was not uncommon for poets to compose anthologies of their entire production with a posthumous printed publication in mind: however, for some reason, the sheets put together by Barbazza, written in beautiful handwriting (a circumstance that supports the hypothesis of their preparation for printing) never reached the printing press. For centuries, Barbazza’s poems were therefore forgotten, at first confined, in all probability, to the archives of the Accademia dei Gelati, of which Barbazza was a member, and then circulated privately, until, in the twentieth century, they reached a bookstore in Bologna which, in 1968, due to cessation of business, decided to dispose of its entire library holdings by auction. It was in that circumstance that the manuscript was purchased, along with other material, by the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, at a time when several newly established American study centers were feeling the need to create valuable libraries for themselves, and consequently purchased en bloc lots they found on the Italian market. In any case, what is important is that this summary of Barbazza’s literary production has been found: it is mostly ecphrastic poems, referring to the works of art that the poet had in his own collection, to those paintings that he had in his house, that he could see every day. Scrolling through the manuscript sheets, then, is a bit like having an inventory of Barbazza’s collection in hand. Identifying Iole was not such an arduous task: the heroine of Greek mythology, known for having subdued Hercules to the point of forcing him to wear women’s clothes while she wore the skin of the Nemean lion and held his club, is the protagonist of a lyric entitled Jole laughing with the lion’s skin by Lodovico Carracci that is well suited to an image hitherto devoid of history (“La bellissima Jole / Che così viva appararne ne’ tuoi colori / Coprir del bianco seno hor non vuole più / Con sotil velo gli animati averi / Ma della spoglia del Leon Nemeo / La clava impogna, / Per maggiore trofeo / Fastosetta deride / Conocchia il filatore Alcide, / Oh, qual vasto si accrescce al tuo penello / Jole in Alcide, Alcide in Jole è bello”).

On the other hand, it is at present only a hypothesis to identify a portrait that had so far provoked long discussions among critics about the identity of the subject, which has so far never been proven: it is the so-called Portrait of a Gonfalonier by Artemisia Gentileschi, exhibited next to the Iole because, and this is the hypothesis presented to the public in the exhibition, it could be a portrait of Andrea Barbazza. In fact, in the manuscript appears the description of a “Portrait of the author by the hand of Roman Artemisia,” which does not describe the painting but, as almost always happened, was content to evoke it (“Pingi qui il mio volto / Appaga, pur rivela, il tuo desio / Che se finito è your heart in mine / You may well also exercise your right hand / With finite master Art; / But, if you long for me to live, to me similar / Cangia l’usato stile, / Come verace, et immortal colore / Da morte al volto se le desti al core”). In 1622, the year in which Artemisia painted the work, signing and dating it, Andrea Barbazza was in Rome, during the years when Rome was ruled by a Bolognese, Pope Gregory XV, born Alessandro Ludovisi, the protagonist of this winter’s other important Roman exhibition, that of the Scuderie del Quirinale, dedicated precisely to the Ludovisi papacy. The Bolognese who, at that juncture, had moved to Rome included both Andrea Barbazza and Guido Reni (the two were close friends, indeed: Andrea Barbazza considered himself a sort of servant of the painter, and the same self-perception was held by Cesare Rinaldi, another friend of Guido’s). Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that Barbazza commissioned Artemisia for an eventual portrait on that occasion. Some knots remain to be clarified: why the subject has the attributes of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, for example, while instead on the pontifical gonfalon the hook could be Barbazza’s election to the Collegio degli Anziani in Bologna in 1607, an office that allowed him to portray himself precisely with the gonfalon.

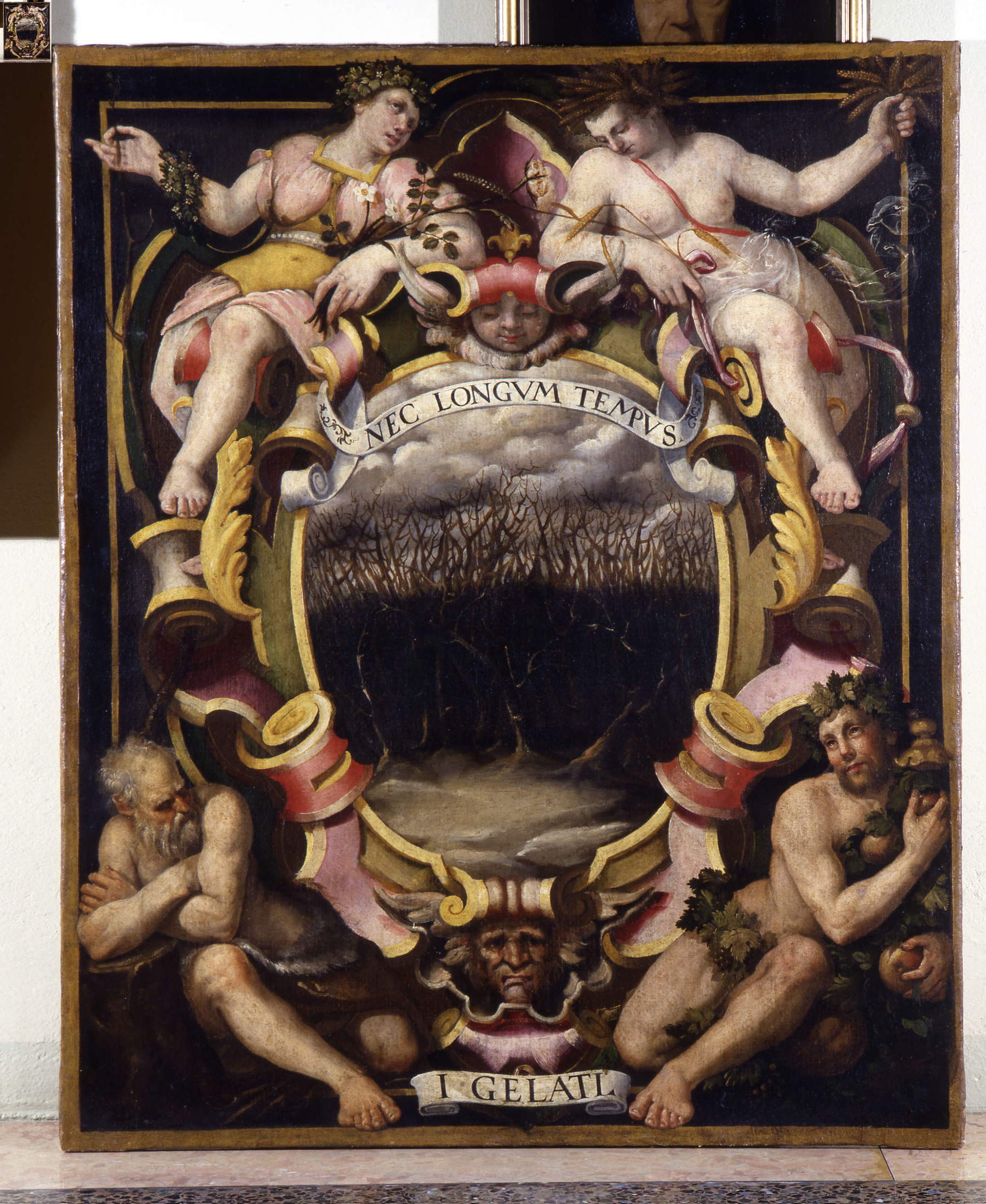

After a section listing the achievements of some Bolognese painters who frequented Roman circles, showing some of their most refined masterpieces always to be read in relation to the poetry of the time (parading an Amor vincit omnia by Gian Giacomo Sementi, whose work was often requested by poets such as Marino and Barbazza themselves, and then a Judith by Lavinia Fontana, another painter praised by Bolognese poets such as Giulio Cesare Croce and Ridolfo Campeggi, and again the Roman Lucretia by Guido Reni), here comes a comparison between the two versions of theAtalanta and Ippomene by Guido Reni, displayed alongside the Strage degli innocenti to which Marino dedicated one of his lyrics, contained in the famous Galeria (“Che fai Guido, che fai? / La man, che forme angeliche dipinse, / Tratta or opre sanguigne? / Non vedere tu, che mentre il sanguinoso / Stuol de’ fanciulli ravivando vai / Nova morte gli dai? / O ne la crudeltate anco pietoso / Fabro gentil, ben sai, / Ch’ancora tragico caso è caro oggetto, / E che spesso l’horror va col diletto”). Last time, the two works were exhibited together in 2023 in Madrid, on the occasion of the great exhibition that the Prado dedicated to Guido Reni, but the Italian public had not seen the two squares together since 1988, the year of the complete monograph curated, precisely at the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna, by Andrea Emiliani: an exhibition so important that it then traveled to Los Angeles and Fort Worth.

Same drawing, different chromatic drafting: brighter the Madrid painting, darker and with a more insistent chiaroscuro the Capodimonte painting, a circumstance that could lead one to consider the Neapolitan version earlier than the Spanish one because of its greater closeness to the works of Guido Reni’s Roman period of the 1910s. TheAtalanta and Hippomenes, a manifesto of Guido Reni’s ideal beauty, is a painting about which much has been written, and whose literary origins have already been clarified, by virtue of the existence of a passage in theAdonis of Marino, composed in the same years in which Guido painted his masterpiece, dedicated to the myth of Atalanta and Ippomene (“Per l’arringo mortal, nova Atalanta / l’anima peregrina, e semplicetta, / corre veloce, e con spedita pianta / del gran viaggio al termine s’affretta. / But oftentimes its course turns away / the adulator sense, which allures it to itself / with the pleasant and playful object / of this pomo d’or, which name has world”). What is not known about the painting is who commissioned it: it seems almost as if the ancient history of the painting has been forgotten, were it not for those verses by Marino that lead one to trace the genesis from the painting back to the cultural milieu of Bologna, and perhaps even more so of Rome, of the early seventeenth century. Inventory records for the two works are very late: anAtalanta e Ippomene by Guido Reni is mentioned in the Gonzaga collections in the late seventeenth century, and it is not even known which version it is (assuming that those in Naples and Madrid are the only two actually produced by Guido’s hand), and then we know that, also in the seventeenth century, a Genoese nobleman in the service of the Spanish crown, Giovanni Francesco Serra di Cassano, had in his hands anAtalanta e Ippomene by Guido Reni that later found its way into the collections of the kings of Spain: it is the work preserved today in the Prado. Even less is known about the Neapolitan painting, since it appears only at the beginning of the 19th century in a Milanese collection, and then arrived in the Bourbon collections. The idea suggested by Giulia Iseppi is that to search for the patron (or rather: the patrons) of theAtalanta and Ippomene we need to look among the literary circles of the early seventeenth century, and in this case in the Accademia dei Desiosi, founded by the Turin cardinal Maurizio di Savoia (who knows, moreover, that he might not also have brigaded to get Andrea Barbazza recognized by the Mauritian Order). The Accademia dei Desiosi certainly brought together Giovan Battista Marino, several high prelates who gravitated around Gregory XV, some students of Guido Reni, and perhaps Guido Reni himself. In 1626, the Accademia produced a kind of diary in which they also spoke of the “fable of Atalanta,” a circumstance that, Giulia Iseppi explained, provided the title of the exhibition: that of Atalanta and Ippomene was a story (indeed, a “fable”) little frequented by the painters of the time, but known to the literati and much frequented by the academicians attended by both Guido Reni and Giovan Battista Marino. Consequently, the name of the patrons of theAtalanta and Ippomene is perhaps to be sought in those prelates who had large rooms in which to display paintings of such considerable size, and who at the same time could fully understand, under the banner of that refined Christian humanism used to reread Greek and Roman myths in a contemporary key, the meaning of Guido Reni’s painting: the Bolognese Ludovico Ludovisi, the Mantuan Ferdinando Gonzaga who was, moreover, a great friend of Barbazza, Maurizio di Savoia himself. A painting perhaps created for one of these prelates and then became the object of desire of some of his other “colleagues,” to the point of leading Guido to paint another version. And then perhaps others.

Here it is, then, the Bologna of the early 17th century, the Bologna of poets and painters whose relationships did not end, as we have seen, at the paper or canvas. The exhibition at the Pinacoteca Nazionale helps to clear the fog on these relationships that were not limited only to the professional sphere. Poets should not be seen as the painters’ sources of inspiration. Or vice versa. Their relationships were closer and more ductile: there were relationships of friendship, relationships of mutual service, relationships of intermediation involving collectors, patrons, other literati, other poets. Relationships that were expressed in those academies, in those circles that were to be considered centers of cultural power alternative to the centers of official knowledge, to the universities. The tale of Atalanta. Guido Reni and the Poets is thus an exhibition of high scholarly value that adds significant, important, fundamental pages to the history of seventeenth-century Italian art.

An exhibition built in an exemplary way, of limited dimensions and therefore useful to avoid a hasty consumption and, on the contrary, to encourage dense and repeated immersion, provided with a correct, elegant and carefully detailed layout (there are also engaging “sound showers” that reproduce audio with readings of the poems related to the paintings), and also equipped with an educational workshop open to all, engaging, in which one runs the serious risk of spending more time than in the exhibition. We will never know how many visitors actually went to the Pinacoteca for this occasion, because there was no separate ticketing (we will only be able to tell if the flows experienced increases in the three months that the exhibition was open), but at least on the media level it seems to see that The Tale of Atalanta did not get much prominence. An exhibition so well designed, so full of novelty, so scientifically sound, s<

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.