Bill Viola, the electronic Renaissance in Florence: the hymn to expectation

One of the surely most interesting moments of the major retrospective that Palazzo Strozzi dedicates to Bill Viola (New York, 1951), is definitely the impact with the public. It hardly happens to see, in an exhibition, groups of people (among them mostly young people) sitting on the floor in front of a work, in silence or at most whispering a few soft whispers to their neighbor, in absorbed contemplation, waiting for something to happen. If we wanted to point to a particular merit of Bill Viola’s videoart, with its sequences stretched to the limit of human endurance, with its surgical slowdowns, with its art history nerdy atmospheres, sometimes predictable but often surprising, perhaps we would not have too much difficulty in identifying it in thealmost nerve-wracking anticipation that his installations are able to arouse. Bill Viola’s art is not only a hymn to slowness, but also a hymn to waiting. That is why it is not far-fetched to say that his works should be taught and shown at school, precisely because of this particular value of theirs.

|

| The exhibition Bill Viola. Electronic Renaissance at Palazzo Strozzi |

|

| The audience in the first room of the exhibition |

Obrist has often insisted on slowness and silence as key factors in visiting a museum and understanding a work of art, especially in contexts where exhibitions have gone through an “accelerator effect,” as per the expression he used in an interview a few years ago. It is as if in the halls of Palazzo Strozzi that tortuous and compulsive motion to which many, too many patched-up exhibitions force the public has disappeared, with the nefarious result that, also accomplice lately to a school that no longer considers the teaching of art history to be strategic, a number of people no longer have (or have never had) any idea how to visit a museum: we see them quickly splashing from one work to the next, transforming a possible opportunity for in-depth study, refinement of critical judgment and, why not, real emotion, into a sort of pre-packaged tour of forced amazement devoid of real insight. Bill Viola’s art simply does not allow this. We need to “claim time,” Bill Viola would say, to give time to ourselves, to let our minds breathe, to make sure that there are spaces in our lives in which time is not constricted within preconstituted rhythms devoted to maximum optimization, but can flow freely, in the best way, for ourselves: this for the artist should be the goal of art. In the catalog of an exhibition thirty years ago, critic Donald Kuspit wrote that Bill Viola plays with our sense of time, questioning our perception of it in terms of duration, perspective or tension and creating in each work a space to allow us to re-establish a genuine relationship with time. Bergson had contrasted spatialized time with real time, the time perceived also and above all inwardly, from a qualitative standpoint: Bill Viola’s art allows us to reappropriate that dimension, this unmeasurable durée in which past, present and future can also manifest themselves in co-presence.

The visitor to the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition is immediately plunged into this reality from the very first room, without much preamble: a room in complete darkness welcomes The Crossing, the first work in the exhibition, a sort of rite of passage conceived as a diptych of videos leaning against each other on opposite sides. On the one we are confronted with the moment we cross the entrance to the room, the protagonist strides toward the audience only to stop and be hit by a flame while, on the other, the flame is replaced by a waterfall: the man then disappears, overwhelmed (or transformed) by the force of the two natural elements, in a work of strong theatricality and great emotional impact. The dilation taken to its extremes makes the video similar to atwo-dimensional work of art, to a painting: the slowness with which the action unfolds gives us a way to linger on all the individual details of the scene, gives us the opportunity to dwell on the details exactly as we would if we were looking at, precisely, a painting, leaves us time to try to provide our own interpretation of the message the artist wants to send us. The audience provides an evocative backdrop to the experience-it is like being in a museum and a movie theater at the same time. There is the sharing spirit of the cinema, but without the audience being rigidly framed in numbered rows: we arrange ourselves freely in the corners of the room, on the sides, sitting on the floor. There is the care and scrupulousness with which works of art are observed at the museum, plus there is theimminence of something that will shortly intervene to modify what we are admiring (and, consequently, to modify our own perception).

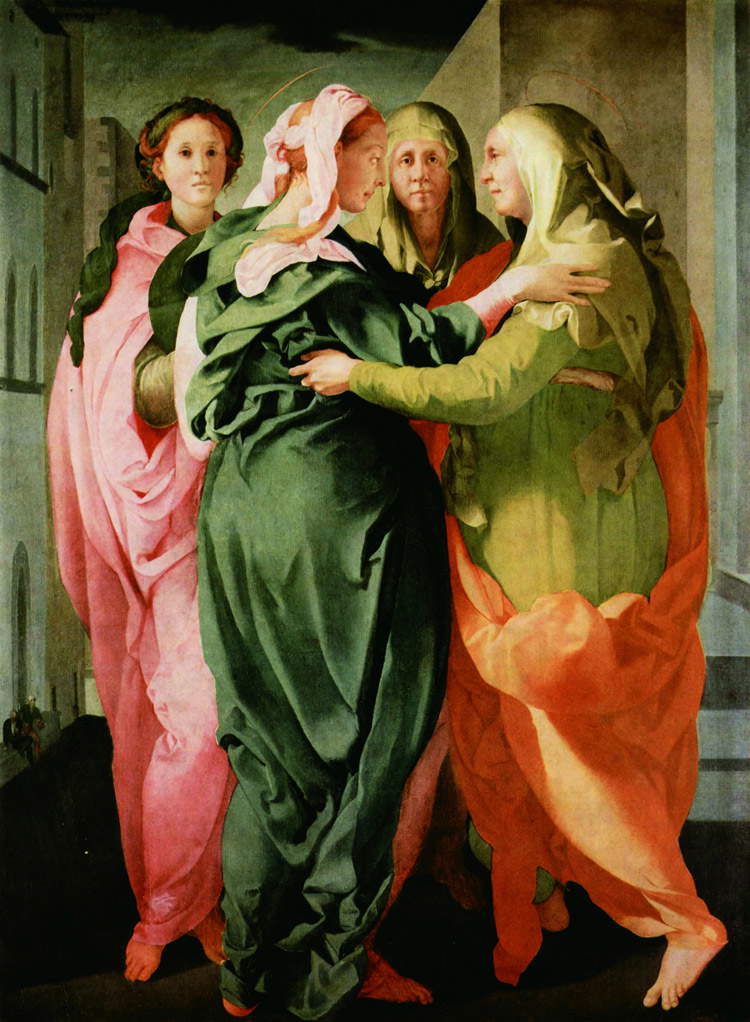

The curators(Arturo Galansino, director of Palazzo Strozzi, and Kira Perov, executive director of the Bill Viola Studio) then consistently decided to place some of Bill Viola’s installations alongside the Renaissance artworks from which the U.S. artist expressly stated that he was inspired. In an article published last month in Engramma magazine, Alessandro Alfieri warburgianly discussed Nachleben in reference to Viola’s works inspired by antiquity: however, if survival is to be spoken of, it must be done not because of the American artist’s unfailing revisitation of tradition (Warburg often availed himself of examples of works in which survival could not be dictated by the artificer’s familiarity with the original source), but because of his ability to bring out, through time, the life of images. The philosopher Giorgio Agamben explained this in one of his essays (which, too, Alfieri cites): “If one were to define in a formula the specific performance of Viola’s videos, one could say that they do not insert images into time, but time into images. And since, in the modern, not movement but time is the true paradigm of life, this means that there is a life of images, which is a matter of understanding.” The dynamism that Viola imparts to his works means that the image that is produced at a given moment (the one in which we observe it for the first time) undergoes a series of transformations that, Agamben further explains, oblige the viewer “to see the video again from the beginning,” with the result that “the immobile iconographic theme is transformed into history.” Time is, in short, still the key: this also explains the absence of a figure from The Greeting, a work that welcomes us to the second room along with Pontormo’s Visitation, the work from which it is inspired.

|

| The room with The Greeting and Pontormo’s Visitation |

|

| Bill Viola, The Greeting (1995; Video-audio installation, duration 10’22"; color video projection on a large vertical screen installed on a wall in a darkened space; amplified stereo sound; Performers: Angela Black, Suzanne Peters, Bonnie Snyder. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio) |

|

| Pontormo, Visitation (c. 1528-1529; oil on panel, 207 x 159.4 cm; Carmignano, Pieve di San Michele Arcangelo. Photo Antonio Quattrone) |

Said the artist, "My encounter with the painting happened in California. I had gone to a bookstore...I see out of the corner of my eye a... new text on Pontormo. The Visitation was reproduced on the cover, and I was struck by the colors. I didn’t know anything about that painting, but I couldn’t stop looking at it. I bought the book and took it home. But I waited months before I picked it up. Eventually, I opened the book, read it, was fascinated by the ideas, the colors of that painter. Thus was born the idea for The Greeting." This last work (the action of which lasts forty-five seconds, but the dilation enacted by Bill Viola brings the video to extend for more than ten minutes) confronts us with a meeting between two women who converse with each other and a third who arrives and whom the others greet. In Pontormo’s work, Saint Elizabeth appears twice to suggest to the viewer the idea that the meeting between the two cousins is an event that takes place over time; Bill Viola, overcoming the fixity of the painting, no longer needs such artifice. Older works, however, might suffer somewhat from this comparison, if only because video, by its very nature, forces the visitor to linger longer to observe the unfolding of an action that, in a painting, is obviously absent. However, one must appreciate the curators’ effort in often putting the viewer in a position to make direct comparisons. In this sense, perhaps the high point of the Florentine exhibition is the room devoted to the Flood: By placing oneself at the right distance (and hoping to be a little lucky in finding the room not overcrowded), it is possible to bring into one’s field of vision both Paolo Uccello’s Diluvio, from the Chiostro Verde in Santa Maria Novella, and, albeit in part, Bill Viola’s The Deluge, a work in which some passers-by walk near a building with classical architecture, from where an unstoppable torrent will then come out and overwhelm everyone. Paolo Uccello’s The Deluge, placed over the entrance to the room, continues the space of the video: it almost seems as if the water of The Deluge springs from the Renaissance lunette.

|

| The room with The Deluge the Deluge of Paolo Uccello |

|

| Bill Viola, The Del uge (2002; panel 3 of 5 in Going Forth By Day, 2002; video-audio installation High-definition color video projected on a wall in a darkened room, duration 36’; stereo sound and subwoofer, 370 x 488 cm. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio) |

|

| Paolo Uccello, Universal Deluge and Recession of the Waters (c. 1439-1440; detached fresco, 215 x 510 cm; Florence, Musei Civici Fiorentini, Museo di Santa Maria Novella, from the fourth bay of the east side of the Chiostro Verde. Photo Library of the Florentine Civic Museums) |

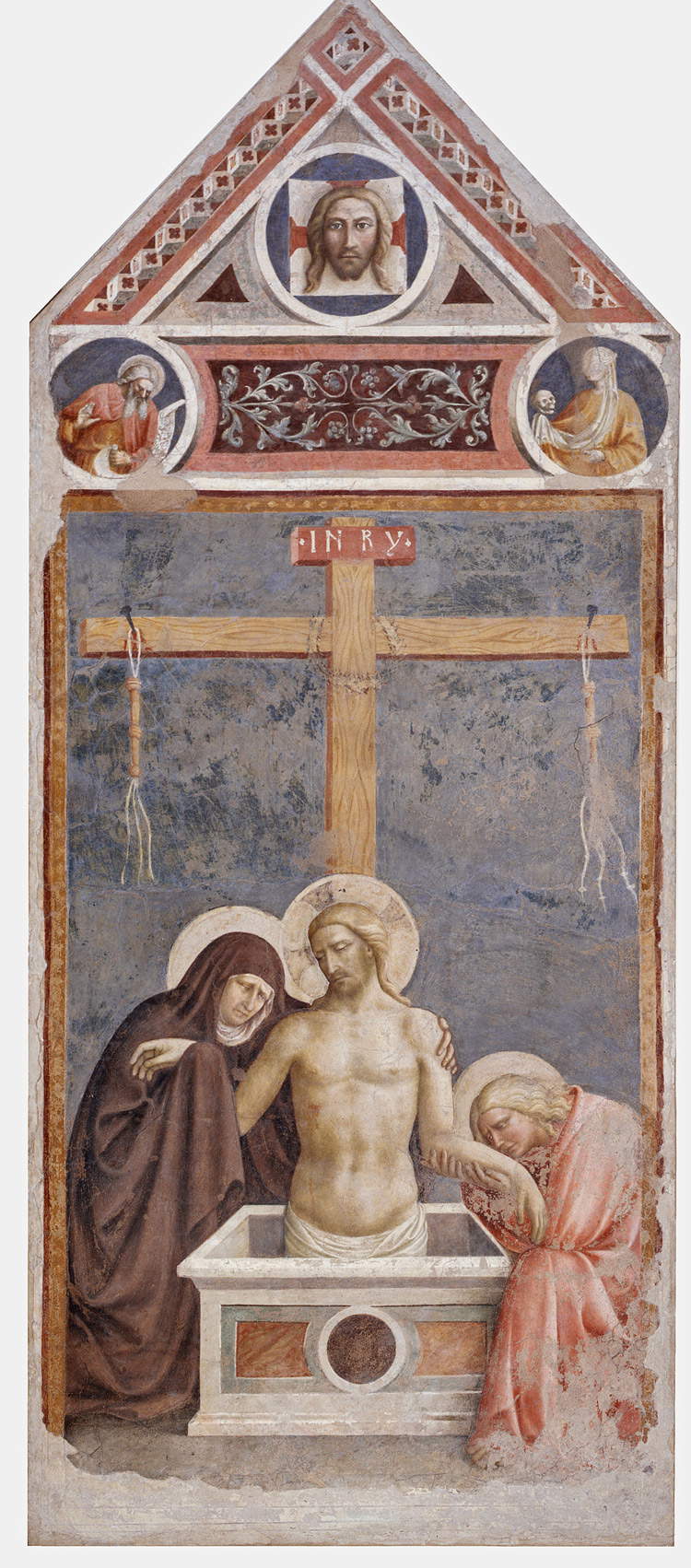

Equally pregnant is the room in which we witness the juxtaposition of Masolino da Panicale ’s Pietà and Bill Viola’s Emergence, the latter a capital work and fundamental to understanding the American artist’s path and imagery: expressly citing the panel in the Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea di Empoli (also in format: and although the Pieta is a detached fresco, Emergence has the measurements and aura of an altarpiece, while the blue background recalls Masolino’s era frescoes), we witness theemergence of a waxy, lifeless body from the tomb at the center of the scene. The young man’s emergence from this sort of well is accompanied by two women who lay him on the ground and, heedless of a cascade of water pouring from the tomb, mourn him and finally cover him with a cloth. The procedure is roughly the same: by giving movement to the images, Viola reinterprets and reinterprets classical images (the viewer can pick up on several quotations, from Raphael’s Deposition in the Galleria Borghese to Michelangelo’s Pieta ) merging iconographies (in this case that of the Pieta, that of the Deposition, that of the Lamentation, that of the Resurrection) and creating a narrative whose value extends beyond the simple plot that unfolds before our eyes: Viola uses metaphors (such as that of water, which, as we have seen, is very frequent in his production: as a child, the artist risked drowning) and recurring repertories, echoing Warburgian Pathosformeln theory, to tell us about life, death and rebirth, emotions and reactions to events, and spirituality. Like Emergence, Catherine’s Room also belongs to The Passions series: a polyptych of small-format videos, whose five panels capture the life of a woman in a domestic interior at five different times of the day (morning, afternoon, sunset, evening and night). The reference, here, is the predella of a polyptych by Andrea di Bartolo dedicated to St. Catherine of Siena, with the difference that while in Andrea di Bartolo’s predella the episodes referred to the lives of four different women, the protagonist in Bill Viola is only one. This is not idle emphasis: the atmosphere of intimacy that the predella panels often succeeded in establishing toward the viewer (as opposed to the main compartments, hieratic in their devout and iconic fixity) is here functional in evoking, again, the cycle of life and nature.

|

| The room with Emergence and Masolino’s Pieta |

|

| Bill Viola, Emergence (2002; high-definition color video rear projection on a wall-mounted screen in a darkened room, 213 x 213 cm, duration 11’40"; performers: Weba Garretson, John Hay, Sarah Steben. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio) |

|

| Masolino da Panicale, Christ in Pity (1424; detached fresco, 280 x 118 cm; Empoli, Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea, inv. no. 32. Photo Antonio Quattrone) |

The major retrospective on Bill Viola finds its natural home in Florence, not only because of the constant references to works by Florentine and Tuscan artists that intricate the American’s work, but also because of his time in the city: on several occasions we are reminded that Bill Viola was in Florence between 1974 and 1976, serving as technical director of art/tapes/22, a production and documentation house for videoart works, and at the Strozzina, where some of his early works are present, an entire section, Firenze Settanta, which evokes the period in which Bill Viola was in the Tuscan capital and which was configured for him as a period of study and direct contact with those images and icons that, as a boy, he had only been able to see in books, as well as of approach to the new technologies that were to make him thatelectronic artist capable of becoming a pioneer of an art form and of carving out a leading role for himself on the world art scene.

One can then wonder about the role, in the exhibition, of works of art from the past, which are often snubbed by the public, which is more inclined, as mentioned above and as is to be expected given the nature of the medium, to dwell on Bill Viola’s videos. Certainly pertinent presences (and it could not be otherwise, given that we find in the exhibition only the works from which Bill Viola declared to have been inspired), but liable to play a double, ambiguous role: that of mere backdrop that ennobles the protagonist’s installations, making the exhibition assume that air of celebration that would certainly, in an apparently paradoxical way, diminish its importance, and yet also that of dense containers capable of giving life to a constructive dialogue between ancient and contemporary, giving substance to Bill Viola’s reflections. The answers to the questions that the exhibition raises will be up to the visitor, who in the meantime can take advantage of an exhibition undoubtedly played on the edge of emotion, but at the same time able to open interesting and stimulating passages on both the absolute and the contingent.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.